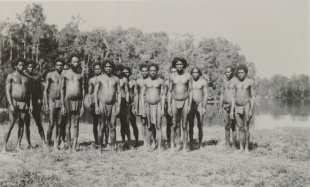

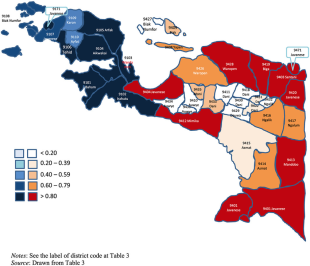

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN PAPUA

Ethnic groups found in the coastal area of northern Papua in Western New Guinea, Indonesia in the provinces of Southwest Papua, West Papua and Papua include the Arfak, Borai, Irarutu, Koiwai, Mairasi, Numfor-Doreri and Wondama. The Dani and Yali peoples live in the interior highlands. The Arfak is a group of related ethnic groups that includes the Hatam, Meyah, Moile, and Sougb. The Biak are a A major ethnic group in the Biak Numfor Regency area. The Maniwak, Mbaham-Matta, Miere, Moru and Sebyar also live northern Papua. the region.

Linguists have identified 250 languages in Papua, half of them spoken by less than a thousand people. In some remote region villages less than a day's walk apart speak completely different languages. In New Guinea there are over 1000 languages, one fifth of the world's total. In mid 1998, the Indonesian government reported the discovery of two “new tribes” in a very remote area of Papua that communicate using sign language.

Many tribes have not been studied very expensively and there is little historical or archeological evidence on them. Some tribes still don't communicate with the outside world. Missionaries attempt to coax them out with mirrors and gifts, but these are rejected and defaced by tribes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NORTHWEST PAPUA AND THE BIRDHEAD OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF WEST NEW GUINEA — EIPO, DAMAL, EKAGI — AND THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

DANI AND PEOPLE OF THE BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, RELIGION, WHERE THEY LIVE factsanddetails.com

LIFE OF DANI PEOPLE OF WESTERN NEW GUINEA: SOCIETY. FOOD, SEXUALITY factsanddetails.com

BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TRAVEL, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

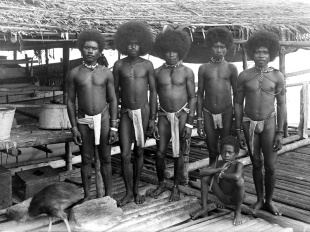

Waropen

The Waropen live in the Waropen Regency of Papua Province in northern Papua (the western half of New Guinea). Also known as the Wonti and Worpen, they primarily speak the Waropen (Wonti) language and the majority of them are Christian. Traditionally, they live in stilted longhouses built in a tidal forest around a men’s house for boys and unmarred men. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania “edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

Most Waropen reside along the eastern part of Geelvink Bay, on the south coast of Yapen Island, and on the mainland from the Kerome River, south of the Mamberamo, to the mouth of the Woisimi River at Wandamen Bay. Waropen is classified as part of the Geelvink Bay Subgroup of Austronesian languages. In the 1990s most lived in fourteen villages along various watercourses, just inland from Geelvink Bay.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Waropen population (as of the early 2020s) is 30,000 and 90 percent are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. They numbered some 6,000 in 1982. Historically, the Waropen language was used in trade, including slave trading, and the Waropen people held considerable power in the region.

Waropen Society and Life

The Waropen cultivate sago and coconuts and fish and raise pigs. Hunting is much less important. Most of their dwellings are large multifamily buildings, each with several apartments for couples and children. There is also a young men's house for boys and unmarried men. Women typically collect firewood, carry water, gather mollusks, and produce sago. Men generally build canoes and houses, as well as hunt and fish using lines and hooks, nets, spears and arrows, poison, and traps. A large trading network formerly extended over all of Geelvink Bay, and pottery was an important imported item for the Waropen. Travel was most often by sea.

Waopen religion is centered around sacred and profane things and ancestor worship.Sorcery can be practiced by anyone. There are initiation rites for both males and females that involve piecing the nose and ears. All of the men of a patrilineage are responsible for the worship of their ancestors. Shamans, or ghasaiwin, are most often elderly women, and one of their primary responsibilities is to recover stolen souls. The theft of a soul is believed to be the primary cause of illness. Waropen people participate in cultural festivals where they wear traditional clothing and dance, sometimes playing the traditional Tifa drum.

The Waropen live in clans, which are localized, nonexogamous (marrying outside the group) kin groups, and localized patrilineages, which are exogamous (marrying outside the group), and prefer marriage between men and the mother’s brother’s daughter. A bride price is required but gifts are exchanged between both families. Polygamy is common but divorce is unusual and can only done after returning the bride price. Traditionally, a group of related brothers lived in one longhouse (ruma). There was an apartment for each of the resident males' wives. Some families lived alone, away from their affiliated longhouse. ~

Several lineages belong to each clan, and some clans and lineages are regarded as senior, giving them greater influence and prestige. Many lineages are also connected through patterned marriage exchanges. Status and influence can be gained through age or by demonstrating kako.

Waropen kinship ties are calculated through the male line and have traditionally been organized through kinship groups called "da" and "ruma bawa," and a customary government structure that includes roles like ruler (Mosaba), commander (Eso), and Rubasa (people's deputy). Each lineage has a headman and the oldest male descendant of the oldest lineage in a clan is recognized as the chief. “Kako” (being rough and cruel) has traditionally been greatly admired. In the old days honorific titles were garnered on the basis of how many people were killed and slaves were taken in battles. In addition to kin-based leaders, there were non-kin chiefs known as serabawa, typically drawn from the senior lineages. These serabawa served primarily as military leaders and generally made decisions in consultation with other influential men.

Sentani

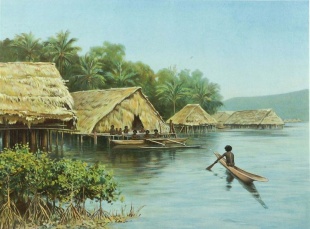

The Sentani people live around Lake Sentani in Papua Province. They are known for their traditional stilt houses built on wooden pilings over the lake, their unique artistic traditions that often feature carvings, and their culture centered on the lake, which they consider sacred. The people have a rich cultural heritage that includes animistic beliefs, specific rituals, traditional crafts like bark painting, and a cuisine based on local resources like sago. [Source: Google AI]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Sentani, Buyaka population in the 2020s was 127,000. Their main language is Sentani and 10 to 50 percent are Christians. Historically, the Sentani economy was based on the abundance of fish and sago found in the lake and surrounding hills. Their worldview is rooted in animism, with the lake being considered a as home to spirits. Their art and architecture often reflect this spiritual connection, with figures representing ancestors and references to the cosmic tree in their mythology.

Constructed on wood pilings, houses and other structures in Sentani villages are linked by boardwalks, allowing the residents to reach any part of the village without the use of canoes. Traditional leadership was hereditary, with chiefs' houses being the most prominent structures in villages. The Sentani also have specific cultural ceremonies, such as the yung ceremony related to paying the head of the dead, and traditional systems of kinship and marriage. Efforts are being made to preserve their culture, including the revitalization of their language through folktales and the promotion of cultural festivals like the Sejuta Hiloi Festival.

Sentani Art

Sentani houses were historically adorned with intricate carvings on the wooden supports, including Y-shaped posts and human-like figures. The houses of the ondoforo (chief) and the large men 's houses (mau) were the most elaborately adorned. The Sentani also create unique handicrafts from the bark of the Khoumbou tree, featuring traditional motifs. Art, including the famous hiloi (often crafted from wood), serves as a symbol of Sentani tradition and identity.

A Sentani house post figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is made of wood and dates to the 19th century. It originates Kabiterau village and measures 91.8 x 21.6 x 21.6 centimeters (36.12 inches high, 8.5 inches wide and 8.5 inches deep) Eric Kjellgren wrote: Until the early 1920s the grandest structures in Sentani villages were the houses of the ondoforo, hereditary chiefs who were the political and religious leaders of society. Although ordinary dwellings were unadorned, the houses of the ondoforo were lavishly decorated with architectural sculpture. Carved into the stout wood pilings that supported the roof and ftoor, Sentani architectural carvings were at once aesthetic and structural. The architectural carvings are of two basic types: finials, typically in the form of human images, which crowned the pilings that supported the house ftoor and, occasionally, the surrounding boardwalks, and tall Y-shaped posts, which supported the central roof beam. Robust in form yet intimate in gesture and imagery, this ftoor-post finial depicts a female figure who appears to hold an infant in her tender embrace. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Only a handful of such "mother-and-child" figures are known from the Sentani region. House-post figures likely depict important clan ancestors, and some scholars suggest that rather than portraying women with infant children, figures of this type depict adult ancestors under the metaphorical protection of the female progenitors of the lineage. Reportedly collected in Kabiterau village, this work once crowned one of the pilings that supported the floor of the house of the local ondoforo. The lower portion of the post was embedded in the lake bed, and the carved portion protruded through the ftoor of the house. According to oral tradition, the first ancestors lived underground and came forth to populate the earth. The placement of the posts, with the bases in the earth and the ancestral images emerging through the floor of the dwelling, may be a symbolic reference to this story.

Sentani roof posts are carved from a single inverted tree, its upper trunk sunk into the lake floor, with the flaring buttress roots at its base left in place to form the winglike projections at the top, at whose junction the roof beam rested. In addition to structural considerations, the inverted trees of the roof posts may be visual references to the cosmic tree in Sentani mythology, which grew downward from the heavens to the earth." The shaft of this example is adorned with the distinctive S-shaped spirals characteristic of Sentani art, which, according to one interpretation, represent clouds that hover between the earth and sky. The openwork filigree of the wings incorporates stylized images of lizards, a common motif on Sentani roof posts, which crawl inward toward the trunk. The ruins of a chief's house at Osei, in Lake Sentani, 1920s. The walls, roof, and floor have decayed, revealing the Y-shaped posts that supported the roof. A carved floor post, adorned with human figures, is visible at the lower right.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: This sculpture once belonged to Jacques Viot and later his collaborator Pierre Loeb, both members of the Surrealist movement in the 1920s and 30s. Viot (1889-1973) was an art dealer who organized some of the first surrealist exhibitions in Paris in the mid-1920s. In part to repay a series of mounting debts to Pierre Loeb – who owned the gallery where these momentous exhibitions occurred – Viot travelled to Dutch New Guinea in 1929 in order to purchase artworks that could later be sold in Loeb’s gallery. Unlike African art, which by that time had become rather "mainstream," Oceanic art was seen as new and exciting, imbued with a transformative potential that could be harnessed by Surrealists in Europe, who filled their private collections with pieces from the region.

Maybrat

The Maybrat live inland on the Bird’s Head (Vogelkop) Peninsula in northwest Papua (western New Guinea) in Southwest Papua province. Also known as the Brat, Mejbrat, Ayamaru Brat, Maibrat and Meybrat, they have traditionally lived in villages centered around a spirit house which itself has been situated where the founding spirit is thought to have emerged from the ground. They are known for speaking the unique "Mai Brat" language, practicing slash-and-burn agriculture, and generally being animists. Few are Christians. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Ayamaru, Brat population in the 2020s was 99,000. In the 1990s, the number of Maybrat was estimated to be around 20,000. About 16,000 Maybrat speakers estimated in 1956. Maybrat territory is shaped by rivers and lakes. Four small lakes anchor the region, each ringed by marshy grasslands that give way to a belt of hilly secondary forest. Beyond this zone rise steep, heavily forested mountains cloaked in primary tropical rainforest. The inhabited areas are threaded with footpaths connecting settlements and scattered with swidden gardens.

Papua Barat Maybrat

Language: The Maybrat speak the Maybrat (Mai Brat) language. Although often described as a language isolate, it is also classified by some scholars as part of the Central Bird’s Head family of non-Austronesian languages, within which it has seven recognized dialects. Centuries of contact with Moluccan traders have left a strong Malay influence on the language, and many Maybrat people now also speak Indonesian.

History: Warfare has traditionally not been a big thing with the Maybrat. After slaving entered their region, the Maybrat took part in armed raids. but that ceased with the establishment of Dutch control and the ending of slaving. In precontact times there was trade both within the Maybrat territory and between Maybrat and non-Maybrat. Indirect contact with outsiders began in the sixteenth century, when Moluccan traders first reached the area in search of slaves and local spices, especially nutmeg. The Dutch arrived on the peninsula in the early seventeenth century, but government influence was not felt in Maybrat territory until the 1920s. Systematic efforts to reorganize the population into registered kampongs did not begin until 1934 and continued well into the 1950s. The largest kampongs typically included a school that also served as a mission church, with teachers—whether Indonesian or Papuan—acting as both educators and missionaries. Most of the region was evangelized by the Protestant church, while the eastern portion came under Catholic influence.

Maybrat Religion and Culture

The Maybrat have a complex system of totemic beliefs and supernatural sanctions and view the universe as a pancake-like island with spirits living on the top and spirits living on the bottom. Spirit houses are set up where the spirits break through from one side to the other. Illnesses are thought to be caused by imbalances of “hot” and “cold” and the violations of taboos. Medical practitioners try to restore the balance. If they are unsuccessful, the Maybrat believe, a person dies and his spirit goes underground to the world of the spirits. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project only two to five percent of Matbrat are Christians. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Each Maybrat settlement territory is tied to a mythic place of origin—a site where the founding dema, a spirit woman and her consort, first emerged to create the human world. The concept of dema is multifaceted: it may refer to a local ancestral spirit, a unifying cosmic principle known as Ratu, or a guiding force for mechar specialists, who practice magic and ritual. Maybrat thought often centers on complementary pairs—hot and cold, female and male, slow-growing and active—and ritual objects, especially small round stones, are chosen for colors or shapes that embody these qualities.

Upon death, a person’s spirit is believed to descend underground to join the regional dema. Although details of funerary rites are incomplete, the deceased’s son is responsible for burial ceremonies, including the burial feast, and receives the skull once the rites are finished. Improper funeral observance allows the spirit to leave its territory and reunite prematurely with the dema, bringing potential misfortune to the living.

Little is known about Maybrat art, though women embroider bark cloth with patterns inspired by imported textiles that form the core of local wealth. Songs and dances also play central roles in the feast cycle. All adults participate to some degree in ritual life, particularly during boys’ and girls’ initiation rites. Only women, however, serve as mechar experts, likely because their work involves invoking and communicating with female dema spirits. These practitioners appear in ceremonies as ritual transvestites and perform divination.

Maybrat Society, Family and Kinship

Society is organized around an extended family with the mother’s brother and mother’s brother’s daughter being important members. Political organization is relatively egalitarian with women attaining leadership positions as well as men. Still, a "first among equals" big-man system based on prestige and wealth exist and the roles that women take are relatively small. Government attempts to reorganize the Maybrat into kampongs had little real effect as of the 1990s. Although such villages exist on official records, Maybrat communities continued to follow their traditional patterns of settlement and social organization. This persistence largely reflects the mismatch between state expectations—based on a Western, male-centered model—and Maybrat social structures, which do not align with those assumptions. Order among the Maybray is maintained primarily through adherence to taboos that govern interpersonal behavior. A complex system of totemic beliefs and supernatural sanctions helps prevent misconduct. Material fines may also be imposed: for instance, if a young man is caught engaging in premarital sex, the woman’s family can demand a substantial payment in cloth to “show respect.” [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriages are regarded as the union of a gardening team, and the worth of a bride is determined by how well she can garden. A bride price of cloth, meat, fish, palm wines and labor is given with the wife’s family reciprocating with presents of lesser value. Most of the cloth received by the wife-taking side goes directly to the bride, forming the core of her new household’s wealth. Polygyny is considered an ideal but is uncommon. A preferred husband is one who is both geographically and genealogically distant from the wife-giving group. Marriages are arranged by the bride’s kin—typically her elder brother—who selects a suitable spouse and negotiates bride-wealth.

Maybrat women are highly respected within marriage. Their gardening labor is essential, their garden produce is considered their own property, and residence with the wive’s community places them near supportive maternal kin. Newly married women first stay briefly with their husband’s mother, but couples soon establish a home near the wife’s father’s maternal relatives. Young children live with their parents, but at initiation age boys move for long periods to the household of their mother’s brother, while girls spend much time with their father’s sister. A typical household includes a husband, wife, their uninitiated children, and often an initiation-age niece or nephew. Mothers care for and discipline young children, while a boy’s mother’s brother and a girl’s father’s sister are responsible for teaching skills and ritual knowledge. Both boys and girls undergo initiation under the guidance of these senior relatives. Rights to garden land pass matrilineally through women. Movable property generally transfers from mother's brother to sister's son, or from father's sister to brother's daughter. Esoteric knowledge follows the same pathways but must be taught rather than simply inherited.

Maybrat kinship emphasizes horizontal relationships—especially ties involving a mother’s brother, sister’s son, and siblings—more than lineal descent. These ties can be strategically emphasized or downplayed. The key domestic unit centers on a person and the opposite-sex siblings and cousins linked through their maternal or paternal aunts and uncles. Two crosscutting moiety-like divisions structure marriage: one divides “shore” and “hill” people; the other is based on ancestral connections to regional dema spirits. These intersecting divisions define wife-giving and wife-taking groups. Kinship Terminology. Formal kin terms are largely Iroquoian, though everyday usage tends toward Hawaiian patterns. Generational distinctions follow a bifurcate-merging system.

Maybrat Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Taro, sago and yams are the staples of Maybrat diet. Protein is derived from flying foxes, wild pigs, kangaroos and opossums killed with blowguns and spears. Grubs, larvae, locusts, lizards, bird’s eggs, mice and frogs are gathered. Some fishing is done in rivers and lakes with traps, poison, baited lines and spears. Meat has traditionally been used mainly for ceremonial exchange rather than daily consumption. Fishing varies by region; it is especially important around the three central lakes, which have been stocked by the government. Fishing methods include poison, traps in dammed streams, baited lines, and spears. Cash crops such as peanuts, green peas, and beans have been introduced, and maize has long been grown in the north for trade. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Government-led kampong formation was meant to bring Maybrat families into nucleated villages, with houses facing a central path and, in some cases, linked to a church-school. Today, however, these planned settlements are mostly empty or only lightly inhabited. Maybrat continue to live in dispersed homesteads situated near their swidden gardens, with each settlement area loosely oriented around a regional “spirit house”—the place where the founding spirit is believed to have emerged from the earth. Houses are wood-framed, pandanus-thatched, raised on stilts, and there are no separate men’s houses.

Men perform the heavier parts of house construction—framing and attaching the thatch—while women prepare the pandanus bundles used for roofing. Both genders participate in clearing garden land, but men build the fences and women handle most gardening work. Men construct river dams and prepare fishing poison; women fish with lines, apply poison, gather stunned fish, and tend fish traps. Spear fishing is done by both sexes, but all other hunting (snaring, spears, blowguns) is done by men. Gathering is considered women’s work. Women also hold household wealth, especially in the form of valuable cloths.

Locally produced items include bark cloth embroidered with designs modeled on imported fabrics, string bags, and the basic tools of gardening, hunting, and fishing—digging sticks, blowguns, fish traps, and lines. Men weave decorative armbands. Houses are wood-framed with pandanus-leaf thatching, and brush is used to build small dams. Land rights follow the female line. A married man gardens on land belonging to his wife’s father’s maternal kin, while unmarried men work in the fields of their mother’s brother’s wife. Since women do most of the gardening and garden produce is considered their property, the notion of “men’s gardens” is largely symbolic.

The Maybrat have traditionally traded local barks, nutmeg and slaves for things like metal knives, cloth and opium, and valued goods like gongs and beads. When the Dutch arrived in the seventeenth century, they expanded the trade goods to include finer cotton cloth, chinaware, and iron. By the nineteenth century, gongs, glass beads, guns, and opium had entered the trade network. Internal trade centered on ceremonial exchange within feast cycles, with woven patterned cloth serving as the main form of wealth.

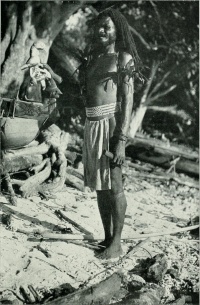

Berik

The Berik live along the Tor River in northern Papua in Sarmi Regency in Papua Province, south of the city of Jayapura. Also known as the Tor, Bonerif, Kaowerawedj, Kwerba, Mander and Soromaja, they are a seminomadic people who eke out a living in a very swampy, rainforest-covered homeland and live in houses set on piles around a cult house, with special peripherals for sex which is forbidden in the main villages. [Source: Terence E. Hays, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Tor River fosters a sense of shared cultural identity among the communities along its banks, who regard themselves as “People of the Tor,” or Torangwa. In this context, “Tor” refers primarily to the Berik, Bonerif, and Mander peoples, and secondarily to their Kwerba neighbors living along the Apauwar and Mamberamo rivers to the west. Rising in the Gauttier Mountains, the Tor River flows northward and enters the Pacific Ocean roughly 25 kilometers east of the town of Sarmi, near 1°50' S, 139° E. The Upper Tor region—comprising foothills, lowlands, and dense tropical rainforest—is marked by braided, debris-filled channels that prevent canoe travel. Below this zone, the Middle Tor cuts through rugged terrain before giving way to the Lower Tor, where the river winds through extensive sago swamps. Canoes can be used in the lower reaches, but in the Upper Tor people rely on watercourses as footpaths whenever possible. Much of this 2,200-square-kilometer region remains unvisited by its widely dispersed, semi-nomadic populations.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Berik population in the 2020s was 1,800. There were about 1,000 Berik in the 1990s. Their size has remained around the same for a century before that due to a low birth rate and high infant mortality rate. In the late 1950s, the Tor Basin population was estimated at about 1,000 people, with perhaps twice that number of Kwerba living just to the west. One particularly striking demographic pattern among the Berik is the severe depopulation recorded between the 1930s and 1960, when low birth rates and infant mortality of 35–40 percent were compounded by unusually high ratios of males to females across all groups in the region—an imbalance so extreme that it threatened the survival of several communities. The cause of this marked masculinization remains unknown.

Language: The Berik language is a Papuan language and has been placed in Tor-Kwerba (Foja Range) language group. Most of the languages spoken in the Tor River region make up the Tor family of Non-Austronesian languages, with Kwerba a member of its own separate family. Throughout the area Berik is used most and has become a lingua franca of the district. Even so Berik is considered endangered because while it is spoken by adults, it is not consistently used by younger generations and it is no longer the norm for all children to learn and use it. inguist John McWhorter has cited Berik as an example of how languages can combine concepts in ways far more diverse than English speakers typically imagine. For instance, the verb form kitobana—meaning “[he] gives three large objects to a male in the sunlight”—incorporates affixes that specify the time of day, the number and size of the objects, and the gender of the recipient. [Source: Wikipedia]

History: Little is known about the prehistory of the Berik beyond oral traditions suggesting that many groups migrated into the area during the twentieth century from the Lake Plains region of the Idenburg River to the southeast. Harsh environmental conditions, combined with raids by the Wares and other neighboring groups to the east and south, contributed to cycles of fission, population decline, and relocation. The Berik had virtually no contact with the Western world until after World War II, when Dutch administrators and missionaries initiated development efforts and conversion programs. Since Papua’s incorporation into Indonesia, very little additional information has been documented; the account presented here relies almost entirely on observations from the late 1950s.

Berik Religion and Ceremonies

The primary religion of the Berik people is Protestant Christianity. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 65 percent are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. Traditionally the Berik recognized three major categories of supernatural beings: 1) ghosts. 2) primordial beings who were never human—such as the sun and moon and 3) Oetantifie, the omnipresent, punitive creator—and former humans who ascended to Heaven without dying. The latter are culture heroes associated with specific tribes, generally benevolent and helpful in activities like hunting, fishing, and healing, though malevolent spirits also exist. Religious leaders are usually healers and adult men who lead ceremonies, with unmarried men increasingly taking the lead in organizing major feasts. [Source: Terence E. Hays, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Life-Cycle Rituals for women are performed only at birth and death. Boys undergo an initiation at the age of 14. They are forcibly taken to a special house located deep in the forest and are secluded for several months and taught about the male cult and the use of special sacred flutes. After these rituals they move from their family house to a bachelors house. The most important community activity is the construction of the cult houses. The feast to mark the completion features a concert of men’s secret flutes and consumption of pigs raised especially for the occasion. The cult house is decorated with wooden phalluses and hanging rattan fruit bats.

Death and Funerals: Both disease and death are attributed to sorcery. The dead have traditionally been wrapped in sago leaves and placed on a scaffold, set in a tree, or buried under a house followed by a ritual burning of all of the dead’s possessions. The shade that remains after the body decomposes is thought to drift through space, parts of it faintly luminous. These shades form their own villages in known but strictly avoided locations. The afterlife is seen as a permanent state of hunger — since sago does not grow where they dwell — which drives shades to roam human settlements in search of nourishment.

Berik Society and Family

Berik villages are the group’s largest and most important social group. Kinship relations are also very important in part because the Berik believe that relatives are required to share food and thus will never cast a spell on them. Marriage is viewed as an economic institution involving elaborate trades and access to sago gardens and other resources. Women are allowed to have sex with her husband’s brother. In the 1980s about 20 percent of men were polygamous and 30 percent were unable to get married and became permanent bachelors because of a shortage of women. Polygyny has traditionally been seen as a sign of weakness rather than prestige. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania “edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

The village is essentially identical with the tribe: a named, bounded territorial unit that functions as a political community. Despite their small size—rarely more than eighty-five people—villages typically include all speakers of a given language and have strong endogamy (marrying with the group). Rivalries among Berik tribes have been pronounced, with each considering itself superior. In the late 20th century, bachelors formed a distinct social group, living together or roaming the forest. They increasingly handled intertribal barter, organized feasts, and sometimes left for European settlements in search of work.

Berik territorial groups are autonomous and may maintain either friendly or hostile relations with neighbors. Their communities are egalitarian, with no hereditary leaders; influence is gained through economic skill or cleverness rather than age. Dutch authorities once appointed village headmen, and mission schools have raised non-Berik teachers to leadership roles. Women, central to subsistence, wield substantial influence, and their disapproval can decisively affect public opinion. Social control relies on collective opinion, ridicule, and conflict; unresolved disputes may end in ostracism or banishment. Most quarrels arise over women and can escalate from personal disagreements to inter-village conflict, sometimes leading to fission if not resolved through ritual or gift exchange.

Two main household forms occur. The Mander maintain independent nuclear-family households, including older co-wives, who share gardening and childcare. In other groups, a “domestic” or “fraternal joint” family—brothers, their wives, and children—forms the basic residential and economic unit, traveling together during food quests. Childcare varies by group: among the Mander, men watch children when women process sago; elsewhere, women in the village care for all children while others work or while men hunt. Land and resource rights are inherited bilaterally, and people often bequeath specific trees or dogs before death. After death, however, nearly all possessions are destroyed: weapons burned, pigs killed and fed to dogs, and fruit trees cut down.

Marriage is a crucial economic institution for men, who depend on wives for sago and must reciprocate with fish and pork. Men typically marry around age twenty-three; women, around seventeen to twenty-two. Ideally, marriage occurs through sister exchange, though the “sister” may be any younger female relative. All four parties must consent, and brides may refuse. Because of demographic imbalances, exchanges are often delayed, requiring the groom to give gifts to his wife’s elder brothers. Despite the ideal, elopements and love marriages are common, and elopement—often with a woman leaving her husband—is the only form of divorce besides death. Tribal endogamy is strongly preferred, resulting in about 90 percent of marriages occurring within the same community. When marriages are exogamous, virilocal residence (the husband’s community) is ideal, but uxorilocality (the wife's community)is equally common due to the need for sago access.

Kinship Descent is bilateral (ancestry is traced through both the mother's and father's sides) but some Kwerba groups emphasize the father’s side, and in the region’s small populations nearly everyone is related. Kinship terminology varies. The Berik system does not mark sex but emphasizes relative age, except for mother’s brother, and uses Hawaiian-type cousin terms. The Mander avoid extending parent or child terms and use an Iroquois-type cousin system, which the Kwerba also use—though Kwerba kinship otherwise leans toward a strongly generational and sex-distinguished pattern.

Berik, Life Villages and Economic Activity

About 90 percent of the Berik’s diet is made of sago, which grows wild in the swamps where they live and has traditionally not been cultivated. Protein comes from hunted wild pigs, cassowaries, lizards, rats, opossums and birds and gathered shellfish, snails, slugs, eggs and fish obtained with bows and arrows or by damming and poisoning small streams. They also eat greens, wild fruits and breadfruit. Pigs are raised from wild pigs caught in the forest and hand fed sago and slaughtered for feasts.

All Berik groups have traditionally been seminomadic, but villages served as semipermanent bases and the centers of social and ritual life. A typical village has eight to twelve pile-built houses arranged in a line along rivers or ridges, or in a circle in forest clearings, with a cult house at the center. Smaller branch villages of about four houses are scattered through the territory and used for sexual activity (forbidden in the main village), refuge from sorcery, and temporary residence during sago processing. In the cult house, rattan figures of fruit bats and the moon, along with carved wooden phalluses used to excite women during ceremonies, are displayed. Feasts feature extensive singing and dancing.

Clothing consists of fern-fiber shields for men. Both sexes wear aprons made from crushed bark and have tattooed made by burning. Each tribe has its own special markings comprised of things such as sago plants, arrows or sago spatulas. Malaria is a serious problem in Berik areas. Pneumonia, filariasis, and yaws are common health problems. Treatments include the rubbing of a salve, blood letting and sucking out the “bad blood.”

Labor is divided by sex. Men trade, carve wood, build houses, hunt, fish, and lead rituals. Both sexes gather wild foods, but women bear most responsibility for subsistence and pig care. Sago processing—done by groups of women from age eight onward—is exclusively female, while men hunt either alone or in bachelor groups. Garden clearing is done by men, with planting shared mainly by older couples.

Beyond canoes (made only in the Middle and Lower Tor), houses are the only large manufactured objects. Men craft arrows collectively, and Berik sago utensils are widely admired. Valued trade items include dogs, cassowary quills, shells, charms, and arrows. ~ Dammar resin—the region’s only cash commodity—is collected mainly by the Mander and traded by Berik intermediaries to coastal merchants. Trade occurs primarily between socially friendly tribes, though “silent trade” is used with enemies. Exchanged goods include dogs, arrows, pork, drums, shells, charms, and more recently, poultry.

Land is collectively held by the tribe. Except for women’s exclusive rights to sago groves, all members may hunt, fish, gather, garden, and reside anywhere in the territory, with rights lasting as long as one continues to visit. Usufruct may be granted to outsiders only by consensus. Individually planted fruit trees or gardens belong to the planters, usually shared with spouses and siblings.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025