ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA

The first determinant when it comes to Chinese architecture is China’s diverse climate. In the north, people traditionally slept on heated platforms called kangs, and the way the houses were built was oriented around the kangs. Mongolians used live in yurts but few do anymore except in the summer when they seek out the steppes for recreational purposes. In the south, houses with split bamboo walls and stilts were common.

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: The houses in rural China “are generally built on the north end of the space reserved as a courtyard, so as to face the south, and if additional structures are needed they are placed at right angles to the main one, facing east and west. If the premises are large, the front wall of the yard is formed by another house, similar to the one in the rear, and like it having side buildings. However numerous or however wealthy the family, this is the normal type of its dwelling. In cities this type is greatly modified by the exigencies of the contracted space at disposal, but in the country it rules supreme. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming height: Revell Company,1899, The Project Gutenberg; Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang,a village in Shandong.]

“The architecture of the Chinese has been compendiously and perhaps not inaccurately described as consisting essentially of two sticks placed upright, with a third laid across them at the top. The shape of some Chinese roofs, however they may vary among themselves, suggests the tent as the prime model; though, as Dr. Williams and others have remarked, there is no proof of any connection between the Chinese roof and the tent. Owing to the national reluctance to erect lofty buildings, almost all Chinese cities present an appearance of monotonous uniformity, greatly in contrast with the views of large cities to be had in other lands. If Chinese cities are thus uninviting in their aspect, the traveller must not expect to find anything in the country village to gratify his æsthetic sense. There is no such word as “æsthetic” in Chinese, and, if there were, it is not one in which villagers would take any interest.

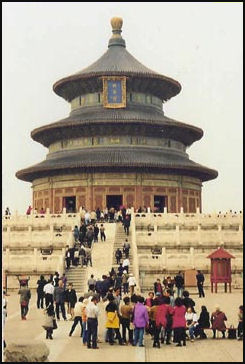

See Separate Articles: TRADITIONAL CHINESE ARCHITECTURE AND FAMOUS BUILDINGS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com/china ; TEMPLE OF HEAVEN Factsanddetails.com/China HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL HOUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOUSES IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CAVE HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SKYSCRAPERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com ; PUDONG AND SKYSCRAPERS AND FAST ELEVATORS IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; SHENZHEN: SKYSCRAPERS, MINIATURE CITIES AND CHINA’S FASTEST-GROWING AND WEALTHIEST CITY factsanddetails.com ; MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINAfactsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com. Edited by professors and graduate students from Columbia, Yale, and the University of Virginia, this site offers thousands of photographic images of Asia's diverse architectural heritage at hundreds of sites in 17 countries. Chinese Architecture china-window.com ; Chinese Architecturechinaetravel.com ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; House Architecture Yin Yu Tang pem.org ; House Architecture washington.edu ; House Interiors washington.edu: Mao-Era Architecture See Wikipedia article on Mao Mausoleum Wikipedia ; Oriental Architecture ; Forbidden City: Book: “Forbidden City” by Frances Wood, a British Sinologist. Wikipedia Article Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites UNESCO Temple of Heaven: Wikipedia article Wikipedia UNESCO World Heritage Site UNESCO

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Architecture: A History” by Nancy Steinhardt Amazon.com “Chinese Architecture” by Qijun Wang Amazon.com; “Chinese Architecture” by Fu Xinian, Guo Daiheng, et al. Amazon.com; “Houses of China” by Bonnie Shemie (1996) Amazon.com; “A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by David Wang Amazon.com “Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation” by Ronald G. Knapp , A. Chester Ong , et al. Amazon.com; “Ritual and Ceremonial Buildings: Altars and Temples of Deities, Sages, and Ancestors” Amazon.com; “Taoist Buildings: The Architecture of “The Grand Documentation: Ernst Boerschmann and Chinese Religious Architecture” (1906–1931) by Eduard Kögel Amazon.com

Chinese Architecture’s Search for an Identity

Matt Turner wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: “When Xi Jinping called for an end to “weird buildings” in a 2014 speech, journalists raced to point out their favorite offenders, from showpieces of contemporary architecture like Beijing’s massive CCTV tower or the Olympic “Bird’s Nest” Stadium, to less known (but no less striking) examples: buildings shaped like coins, sages, various teapots, and even the USS Enterprise. In comparison to these architectural oddities, Xi praised traditional Chinese architecture and the values it inspires (primarily loyalty to the state). [Source:Matt Turner, Los Angeles Review of Books, China Channel, April 16, 2018]

“But while it’s not hard to read between the lines of his speech, it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly Xi means by traditional Chinese architecture. Most Chinese cities are hodgepodges of styles: not only the showpiece buildings and skyscrapers nestled next to old courtyard homes and lanes, but also shopping and office complexes, such as Taikoo Li Sanlitun in Beijing (site of the infamous Uniqlo sex video that surely violates traditional values), or the SOHO complex across the street from it, which looks like a set from Logan’s Run. There are also the gaudy new apartment complexes for the nouveau riche, with flashy English names like “Yosemite” and “Long Beach New Money.” And filling in much of the space between these notable buildings are the soviet-inspired socialist housing compounds — danwei — often left in states of disrepair.

“At present, the Beijing government is forcefully removing much commercial activity from its old neighborhoods in order to “beautify” them. When Qianmen boulevard — a gritty, vibrant commercial hub just south of Tian’anmen Square — was beautified in 2008, much of that street was torn down before being reconstructed in imitation of what Qianmen boulevard is supposed to have looked like during the Qing dynasty — except without the grit, vibrancy, or even people. If Qianmen boulevard is any example of what’s to come, “no more weird buildings” might be a license for the government and real estate developers to construct their own versions of the Chinese past.

Chinese Architectural Features

A hall in the Forbidden City Important buildings have traditionally been built on a platform or terrace of pounded earth covered by brick or stone. The terraces are reached by a dozen or more steps and are adorned with stone balustrades and sculptures. Some Chinese buildings feature balconies covered with elaborate iron and woodwork. They are often painted bright red, gold and green, colors associated with good luck, and hung with signs, tasseled lanterns, and silk banners.

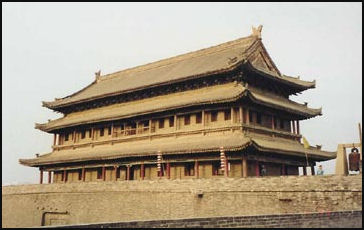

Traditional Chinese buildings have tile roofs with swooping eaves. Walls are usually made of brick or wood. The tile roofs are gray for ordinary buildings, yellow for imperial palaces and blue or green for other important structures. The upturned eaves are elaborately carved with extraordinary detail and are works of art in their own right. Sometimes bells hang from the eaves.

Traditional arch gate features include carved flowering trees, peacocks and lucky bats. Painted red and gold, they are placed at city gates and in stores and restaurants. Not merely decorative, they were strategically placed to ward off evil spirits. The carvings, spirals and swirls are meant to confuse them further. The entrance to palace often had a large water tower. Palaces of the Machu emperors at Chengte featured exposed unadorned cedarwood beams which gave of a fragrant scent that is also a natural insect repellent.

Guardian Lions are placed in front of houses, palaces or temples. They are there because people believe in their protective powers. Often they come as a pair, the male holding a ball that represents the world under his paw, the female protecting a lion cub. [Source: Barbara Laban, The Guardian, February 8, 2016]

Feng Shui and Homes, Buildings and Cities

Many buildings are laid out with the principals of feng shui in mind. “Feng shui” is the practice of bringing about good fortune among the living, the dead and the spiritual world by making sure objects placed in a landscape or space are in harmony with the universe in such a way that they optimally draw on sources of “qi” (cosmic energy or life force). Also known as geomancy, ifeng shui is often expressed in terms of Chinese and Taoist cosmology and is said to be over 3,500 years old.

The five directions of Chinese cosmology and feng shui are north, south, east, west and center. South represents light and brings good luck. North represents darkness and brings bad luck. Accordingly, doors of houses should not face north of northwest: they should face south. The entire house should be oriented towards the south with mountains to the north to block the bad luck from entering and keep good luck from escaping. The best location is at the foot of a mountain, facing a river. Waters helps attract qi. Buildings with a square plan help hold it firmly.

The five directions of Chinese cosmology and feng shui are north, south, east, west and center. South represents light and brings good luck. North represents darkness and brings bad luck. Accordingly, doors of houses should not face north of northwest: they should face south. The entire house should be oriented towards the south with mountains to the north to block the bad luck from entering and keep good luck from escaping. The best location is at the foot of a mountain, facing a river. Waters helps attract qi. Buildings with a square plan help hold it firmly.

The location of the family alter, the orientation of the house and the arrangement of the furniture should be in harmony. Bedrooms should face the sun and stairway should’t be visible from the front entrance. Qi is believed to enter through the front door and exit through the toilet.

Walls can be constructed at certain angles to attract positive energy. Doors can be adorned with coins bearing the names of famous emperors to attract good luck. Fountains in corners are sometimes used to deflect bad energy from the sharp angles of nearby buildings. Mirrors are also used to deflect bad energy. Cell phones are believed to disrupt feng shui. Thriving plants are signs that qi is plentiful.

Entire cities have been laid out according to feng shui principals. In the old days many buildings in Beijing were oriented with the feng shui in mind, namely with their backs towards the north and the mountains and the their fronts facing towards water and the south. Ideally, feng shui masters are consulted before building are built and designs are drawn up. It is not unheard of for recently constructed buildings to be torn down, or for people to refuse to occupy them, because they are out of harmony or face the wrong direction. Sometimes the buildings can be saved if certain countermeasures are taken, such as locating mirrors at key areas. Other times people are undeterred and move in anyway.

See Separate Article FENG SHUI: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, GRAVES, HOMES, BUSINESS AND LOVE factsanddetails.com ; IMPORTANT CONCEPTS IN FENG SHUI factsanddetails.com ; FENG SHUI, QI AND ZANGSHU (THE BOOK OF BURIAL) factsanddetails.com

$30,000 Penalty for Messing Up a Building’s Fengshui in Beijing

In 2019 a court in Beijing ordered a defendant to pay a $30,000 penalty for maligning a building’s feng shui. Javier C. Hernández and Albee Zhang wrote in the New York Times: A Chinese court has ordered a media company to pay nearly $30,000 to a real estate developer after it published an article that suggested a flashy building in Beijing violated the ancient laws of feng shui and would bring misfortune to its occupants. The Chaoyang District People’s Court in Beijing ruled on Wednesday that the media company, Zhuhai Shengun Internet Technology, had damaged the reputation of the building’s developers, SOHO China, one of the largest real estate companies in China. [Source: Javier C. Hernández and Albee Zhang, New York Times, April 11, 2019]

“SOHO China sued Zhuhai Shengun the fall of 2019 after it published a critical blog post about the Wangjing SOHO, a trio of sleek towers in northeast Beijing designed by the renowned architect Zaha Hadid. The post, written by a feng shui expert, argued that the building had a “heart-piercing” and “noxious” energy that had led to the downfall of its tenants, including several promising technology start-ups. The decision by the Beijing court reflected a broader effort by President Xi Jinping to more strictly control independent media and to stop the spread of misinformation and “superstitious” viewpoints online.

“The case highlighted the importance of feng shui in the real estate business in China. Many people pay a premium for homes and offices designed to be in harmony with nature, and reports of bad feng shui can haunt new developments. SOHO China has said that the article, which was widely circulated online before it was deleted, adversely affected its ability to attract customers. Wangjing SOHO generates more than $66 million in rent each year, according to court documents. “We cannot accept the use of feudal superstition to slander this building,” Pan Shiyi, the chairman of SOHO China, wrote on Weibo.

Chinese Temple Architecture

Chinese temples — whether they be Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian — have a similar lay out, with features found in traditional Chinese courtyard houses and elements intended to confuse or repel evil spirits. Temples are usually surrounded by a wall and face south in accordance with feng shui principals. The gates usually contain paintings, reliefs or statues of warrior deities intended to keep evil spirits away. Through the gates is a large courtyard, which is often protected by a spirit wall, a another layer of protection intended to keep evil spirits at bay. The halls of the temple are arranged around the courtyard with the least important being near the entrance in case evil spirits do get in.

Chinese temples — whether they be Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian — have a similar lay out, with features found in traditional Chinese courtyard houses and elements intended to confuse or repel evil spirits. Temples are usually surrounded by a wall and face south in accordance with feng shui principals. The gates usually contain paintings, reliefs or statues of warrior deities intended to keep evil spirits away. Through the gates is a large courtyard, which is often protected by a spirit wall, a another layer of protection intended to keep evil spirits at bay. The halls of the temple are arranged around the courtyard with the least important being near the entrance in case evil spirits do get in.

There are more than 25,000 Buddhist pagodas in China, with 161 declared as national priority protected sites, including multi-storey pagodas, multi-eave pagodas, warrior-pedestal style pagodas, overturned-bowl style pagodas and single-layer style pagodas. According to architectural structure, they can be divided into wooden structure, brick structure, stone structure, brick-stone structure, masonry-wood structure and so on. The Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian is an outstanding representative of wooden structure pagodas.

Chinese temples are often comprised of many buildings, halls and shrines. They tend to be situated in the middle of towns and have north-south axises. Large halls, shrines and important temple buildings have traditionally been dominated by tiled roofs, which are usually green or yellow and sit atop eaves decorated with religious figures and good luck symbols. The roofs are often supported on magnificently carved and decorated beams, which in turn are supported by intricately carved stone dragon pillars. Many temples are entered through the left door and exited through the right.

Pagodas are towers generally found in conjunction with temples or viewed as temples themselves. Some can be entered; others can not. The Chinese have traditionally believed that the heavens were round and the earth was square. This concept is reflected in the fact that pagodas have square bases rooted to the earth but have a circular or octagonal plans so they look round when viewed by the gods above in the sky.

Early Chinese-style pagodas were modeled after Indian stupas. Pagoda architecture arrived with Buddhism but over the centuries developed a distinctly Chinese characteristics that influenced the architecture in Japan and Korea and other places.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE TEMPLES factsanddetails.com CONFUCIAN TEMPLES, SACRIFICES AND RITESfactsanddetails.com; RELIGIOUS TAOISM AND TAOIST TEMPLES AND RITUALSfactsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES AND MONKS factsanddetails.com

Chinese Temple Features

Temple under construction

Many temples have courtyards. Often, in the middle of the courtyard is a small bowl where incense and paper money are burnt. Offerings of fruit and flowers are left in a main hall at the intricately-carved altars, often decorated with red brocade embroidery with gilded characters.

Traditional Chinese temples contain wall paintings, carved tile walls and shrines to gods and ancestors that in turn are wonderfully decorated with wood carvings, murals, ceramic figures and plaster moldings with motifs that the Chinese regard as auspicious.

On the outside of temples there are often stone walls with simple carvings; gates with statues of fanged, bug-eyed goblins, intended to keep evil spirits away; and monuments of children who displayed filial piety to their parents and virgins who lost their fiances before marriage but remained pure their entire life.

Wealthy Chinese temples often contain gongs, bells, drums, side altars, adjoining rooms, accommodation for the temple keepers, chapels for praying and shrines devoted to certain deities. There is generally no set time for praying or making offerings — people visit whenever they feel like it — and the only communal services are funerals.

At Chinese temples orange and red signifies happiness and joy; white represents purity and death; green symbolizes harmony; yellow and gold represents heaven; and grey and black symbolize death and misfortune. Swastikas are often seen on Chinese temples. The Chinese word for swastika (wan) is a homonym of the word for "ten thousand," and is often used in the lucky phrase "chi-hsiang wan-fu chih suo chü" meaning "the coming of great fortune and happiness." See Hinduism, Buddhism

Chinese House Architecture

In the north, where wood is scarce, dwellings and walls have traditionally been made of stone, tamped mud or sun-dried bricks reinforced with straw. In the south homes have traditionally been made with wood, brick or woven bamboo.

A traditional large, upper-class house has a single story, tile roof, a courtyard, fluted roof tiles, and stone carvings. Some have ornate lattice windows, deep red painted pillars, carved dragons and courtyard fish ponds. Old homes had paper windows and coal stoves and smelly latrines in the backyard. There were no indoor toilets, Coal was burned for heat.

Built to harmonize with nature, the traditional house of Ming dynasty scholar consisted of a reception hall, bedroom and study placed around a series of courtyards. The house faced south in accordance with geomacy laws and had a high ceiling, to create the illusion of space, and had fan-shaped windows and wooden columns.

In century-old communal homes the grandparents sleep in one area, aunts and uncles in another. Sometimes children sleep in a converted barm above the pig pens and the parents sleep over the open pit that serves as a communal toilet.

Book: “Yin Yu Tang: The Architecture and Daily Life of a Chinese House” by Nancy Berliner (Tuttle, 2003) is about the reconstruction of a Qing dynasty courtyard house in the United States. Yun Yu Tamg means shade-shelter, abundance and hall.

See Separate Articles HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL HOUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOUSES IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CAVE HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Chinese Courtyard Houses

A traditional Chinese house is a compound with walls and dwellings organized around a courtyard. Walls and courtyards are built for privacy and protection from fierce winds. Inside the courtyard, whose size depends on the wealth of the family, are open spaces, trees, plants and ponds. In the inner courtyards of rural homes, chickens are often kept in coops and pigs are allowed to roam inside small enclosures. Covered verandas connect the rooms and dwelling.

Rural homes are typically built on one, two, three or four sides of an enclosed courtyard. Sometimes one family owns all the units around the courtyard, sometimes different families do. Most houses have peaked tile roofs although slate roofs are common and thatch is still used in some places. In high density areas multistory houses built in rows along streets predominate. They have a courtyard in the front or the back and have a flat roof. In commercial areas families often live upstairs and have a shop or business or animals or storage in the bottom floor.

Many urban homes are one-story courtyard homes too. A typical courtyard house in a hutong in Beijing has an entrance on the south wall. Outside the front door are two flat stones, sometimes carved like lions, for mounting horses and showing off a family’s wealth and status. Inside the front door there is freestanding wall to block the entrance of evil spirits, which only travel in straight lines Behind it is the outer courtyard, with servant’s quarters to the right and left. The family traditionally lived in the inner courtyard towards the back of the north wall.

Poor Construction Techniques in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “It appears to be a general defect in the architecture of the Chinese, that in the construction of their buildings, the base is the part which receives the least attention, and upon which the smallest expenditure is bestowed. Millions upon millions of people in China never in the whole course of their -lives see a mountain, or even a hill. Where there are no mountains, stone is sure to be very expensive, and for building purposes, so far as the bulk of the population is concerned, may be said to be practically unknown. The next best substitute is brick, and owing to the high price of fuel, Chinese bricks are almost certain to be very imperfectly baked. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

The mud of which they are composed is thrown loosely into the mold, the surface is scraped to a rough level, and when the brick is sufficiently sundried to bear transportation, it is placed in the kiln. Owing to the fact that it has not been pressed, and that it has been only half burned, the completed brick is full of cavities, and is almost as porous as a sponge. Wherever the soil is impregnated with soda, as is the case in a large part of the great plains, the soda is drawn up by capillary attraction into the bricks, and also into the structure above, which gradually scales away, at the base, till it comes to. resemble a wall of cheese which has been persistently nibbled at by rats. To counteract these results, various substances such as stfaw, thin boards, etc., are introduced above the foundation, but these are merely palliatives, and do very little to hinder the disintegration, which is often so rapid, that in a few years it becomes necessary to renew the foundation a little at a time without disturbing the wall above.

“Besides the inherent defect of the bricks, Chinese builders almost invariably add two others, too shallow an excavation for such foundation as there is, and the use of a very insufficient quantity of lime. It is not uncommon to see a brick wall laid almost upon the surface of the ground and not unfrequently with no lime at all, in situations where a foreign contractor would dig a trench, five feet deep and use lime by the ton. The object which the foreign builde'r has in view is durability, the object which the Chinese builder has in view is economy of materials. Whoever wishes to see an example of this defective construction on an immense scale, in a situation where one would have looked for more thorough work, has but to walk for a few miles along the base of the wall surrounding the Imperial city in Peking. It would seem as if the only Chinese structures which are sure to be adequately built, are the pawn-shops, which are in reality, a kind of treasure-houses, in which security is of capital importance.

Communist Architecture in China

Typical Communist buildings include concrete boxes that a few traditional elements such as an upturned eaves. The style has been referred to as "swimming pool architecture" with additions that look "ill-fitting wigs." In the Mao era, families were moved into concrete apartment blocks or were jammed into courtyard dwelling — built for a single family — with several other families. The central courtyard was filled with crude brick compounds. In some cases courtyard houses was razed and replaced with "work compounds," where housing and factories were combined within walled enclaves. Most of the concrete apartment buildings built in the 1950s and 60s were four to six stories tall. Ones built today are much higher.

In a review of the book “Beijing Danwei” Matt Turner wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: Tracing the development of the socialist housing compound from an organizational tool for work (having been expressly made to distribute hierarchy) to its architectural style, the editors of Beijing Danwei see the danwei as a cross-pollinated effort of traditional Chinese housing models with Western modernism. Bornini and De Pieri and their contributors even go so far as to argue that danwei socialist housing compounds are a better encapsulation of modernism than some of their European counterparts: “Existing danweis appear particularly capable of … serv[ing] as a matrix for the construction of a new type of contemporary city.” They depart from the old to forge something much more modern and “Chinese” than a re-imagined architectural past. The blocky danwei compounds may not look particularly Chinese, but they expressed the new social hierarchies of socialist China. “Of course, even in today’s “socialist” China few people want to live in danweicompounds — often in a state of disrepair, they seem overly utilitarian and outdated. Siheyuan courtyards are more appealing, but only when outfitted with modern facilities and removed of their current residents. [Source: Matt Turner, Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel, April 16, 2018; Book: Beijing Danwei:Industrial Heritage in the Contemporary City, edited by Michele Bonino and Filippo Di Pieri]

The buildings around Tiananmen Square and the main museums in Beijing are the best representations of the Chinese Stalinist architecture. Occupying almost the entire western side of Tiananmen Square, the Great Hall is a Stalinist monolith with 300 rooms and 170,000 meters of floor space and was built in only 10 months in 1958 and 1959. Some of the rooms are quite large and lavish. Other look like lobbies in shabby Chinese hotels with all the chairs lined against the walls. Each year in March the NPC meets in the "The Ten Thousand People's Meeting Hall," which seats 10,052 people.

In a review of the book “Red Legacies in China”, Xing Fan wrote: “In Chapter 2, “Building Big, with No Regret,” Zhu Tao examines “building big” as a socialist legacy in the People’s Republic of China. Zhu first examines the Great Hall of the People, the core of the “Beijing’s Ten Great Buildings” project, within the historical, ideological, and cultural context of the Great Leap Forward, delineating its twelve months of planning, design, and construction. Zhu further discusses the socialist legacy in today’s China and counters two generalized views of the “building big” concept — as either a Chinese imperial heritage or a strategy shared by international dictators of grandiose monumental buildings. Emphasizing the context of modern and contemporary China, Zhu explores how the notion of “bigness” is deeply rooted in the ideological foundation of nationalism, how the pursuit of “bigness” exerts a sweeping influence in China, and how “bigness” stands at the core of a paradox: mega-buildings serve as landmarks of a developing modern socialist China, yet they are constructed in a “State-Capitalist style”. [Source: Xing Fan, Review, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017] Book “Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution” (Harvard University Asia Center, 2016), edited by Jie Li and Enhua Zhang.

See Separate Articles TIANANMEN SQUARE AREA AND MAO'S MAUSOLEUM factsanddetails.com MUSEUMS IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com

Chinese Towns and Cities

Shanghai neighborhood

Cities and towns in China traditionally have had a south-facing rectangle wall surrounding a grid of public buildings and courtyard houses with similar symmetrical layouts. Many modern towns are centered around a government compound with an ugly modernist sculpture out front, accompanied by Communist slogans that are supposed to generate and image of modernity.

Most Chinese cities are ugly, and people complain they all look alike and have very little to offer. Many are dominated by blocky cement buildings, crumbling apartments, dilapidated factories and pollution-belching smokestacks. Exposed power lines are piled on top of one another. The air is chocked with dust and dirt from construction projects.

China has a makeshift impermanence to it. Zoning rules and centralized planning seems non-existent. There are few parks, and typically they have few trees and look filthy and run down. Sidewalks start and stop, stairways are steep, buildings are often thrown up in a very haphazard manner, and beauty parlors and shops are often found in houses in residential districts.

A typical Chinese city has wide roads, cycle lanes, several universities, a number of technical institutes, hospitals and a medical school. Even mid-size cities have several million people, a skyline, an airport expressway, a large wall-off industrial zone and fancy condominiums.

City Neighborhoods in China

“Hutongs” are the mazelike, old neighborhoods in Beijing made up of traditional quadrangle courtyard homes lined up along on narrow streets and alleys and often built in accordance with the principals of feng shui. In the pre-Mao-era, many residences were occupied by single extended family units and had spacious open air courtyards. But after Communists came to power the houses were divided and occupied by several families and the courtyards were filled with shanties. In many cases a house occupied by one family was occupies six or seven. The term "hutong" is derived from the Mongolian term for a passageway between yurts (tents). It refers to both the traditional winding lanes and the traditional old city neighborhoods.

Hutongs are comprised mostly of alleys with no names that often twist and turn with no apparent rhyme or reason. They are fun to get lost in but near impossible to find anything in. The houses lie mostly behind gray brick walls and are unified into neighborhoods by public toilets and entranceways that people share. Heating is often provided by smoky coal fires that occasionally asphyxiate house occupants. Public toilets and showers are sometimes hundreds of meters away from where individuals live.

Many of the alleys are too narrow for cars and the commercial buildings are too small for anything larger than family-owned shops. Next to small parks or standing alone are exercise stations with bars and pendulums and hoops and things like that, where older people like to gather and hang out and occasionally do a couple of exercises. In the morning residents scamper with their chamber pots to the public toilets. Vendors arrive mid morning with their three-wheeled carts, each crying the product or service the are selling: toilet paper, coal, recycling or knife-sharpening

In Beijing, Shanghai and elsewhere, old homes, old building and entire old tightly-knit neighborhoods have been torn down to may way for skyscrapers, offices complexes, shopping malls and other forms of modern development. Tens of thousands of urban residents have been forced to move or have been evicted.

See Separate Articles HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com HUTONGS AREAS AND SIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Urban Development in China

In China, there are surprising number of garish, over the top apartment buildings, office buildings, shopping areas and even industrial parks. In some places pink, rose, tangerine and even magenta buildings have become very popular. Lotus-blossom-shaped rooftops and the prolific use of reflective and tinted glass are also in vogue. The problem is especially acute in southeast China, with a particularly high concentration of pink building in the city of Zhongshan, where many ugly building can not find renters.

Another trend is to copy foreign designs or hire foreign architects who make a quick buck on slap dash designs. In the worst case the architect designs a flashy facade and behind it is an unsafe building lacking adequate escape routes. Almost as bad is when developers pick the flashier aspects of a design and ignore or minimize everything else. Many respected foreign architects who have worked in China have horror stories of how their designs have been bastardized.

There is lot of pressure to do projects as quickly and cheaply as possible. There are also numerous ill-conceived projects in China. Many developers make big money by pocketing part of the projects construction cots, guiding contracts to construction companies in which they have stake.

Owen Guo wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: “China has at least 10 White Houses, four Arcs de Triomphe, a couple of Great Sphinxes and at least one Eiffel Tower. Now a version of London’s Tower Bridge in the eastern Chinese city of Suzhou has rekindled a debate over China’s rush to copy foreign landmarks, as the country rethinks decades of urban experimentation that has produced an extraordinary number of knockoffs of world-renowned structures. This week, photographs of the bridge were posted online by various news outlets. One headline proclaimed: “Suzhou’s Amazing ‘London Tower Bridge’: Even More Magnificent Than the Real One.” Indeed. Suzhou’s urban planners had clearly stepped up their game. The bridge, completed in 2012, has four towers — compared with the two spanning the Thames in London — making room for a multilane road. “Cars and pedestrians crowd the bridge and its observation platforms. At night, the towers are bathed in blue and yellow light. Not surprisingly, it has also attracted couples eager for a European sheen to their wedding photographs.[Source: Owen Guo, Sinosphere, New York Times, March 2, 2017]

Plastic palm trees

“Suzhou, in the eastern province of Jiangsu, is probably most famous for its ancient gardens and tranquil waterside views. Often called the Venice of the East, it features some of China’s most exquisite traditional architecture, with whitewashed courtyard houses and meandering walkways above lotus-carpeted ponds. (The Astor Chinese Garden Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was modeled after a house in Suzhou.). Nevertheless, Suzhou, too, has joined the scramble of Chinese cities in recent years to erect clones of famous foreign structures, partly as publicity stunts and partly to attract business.

Image Sources: CNTO and Xinhua

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021