CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES AND PAGODAS

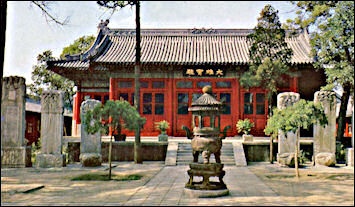

Fayuan Temple Main Hall

Buddhist temples are generally a cluster of buildings — whose number and size depends on the size of the temple — situated in an enclosed area. Large temples have several halls, where people can pray, and living quarters for monks. Smaller ones have a single hall, a house for a resident monk and a bell. Some have cemeteries.

Buddhist temples incorporate pagodas, whose original design h came from India around the A.D. first century, the time when the religion was introduced to China. These temples also display statues of the Buddha, sometimes enormous sculptures in gold, jade, or stone. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ Before the end of the fifth century there were reportedly more than 10,000 temples in China, north and south. Some were undoubtedly small, modest temples, but in the cities many were huge complexes with pagodas, Buddha halls, lecture halls, and eating and sleeping quarters for monks, all within walled compounds. These temple complexes provided a place for the faithful to come to pay homage to images of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and meet with clergy. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv;Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

There are more than 25,000 Buddhist pagodas in China now, with 161 declared as national priority protected sites, including multi-storey pagodas, multi-eave pagodas, warrior-pedestal style pagodas, overturned-bowl style pagodas and single-layer style pagodas. According to architectural structure, they can be divided into wooden structure, brick structure, stone structure, brick-stone structure, masonry-wood structure and so on. The Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian is an outstanding representative of wooden structure pagodas.

The best evidence of the interior decoration of early temples is found in the surviving cave temples. Although only a few wooden buildings have survived from the Tang period or earlier, hundreds of cave temples have survived. Here we offer glimpses of the three most famous cave temple complexes, Dunhuang in Gansu Province, Yungang in Shanxi Province, and Longmen in Henan Province.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism in China Buddhist Studies buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in China Wikipedia Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ;

Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ;

East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; Mahayana Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ;

The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ;

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ; Chinese Religion and Philosophy: Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com; CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHISM TODAY factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM VERSUS THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TEMPLES factsanddetails.com CONFUCIAN TEMPLES, SACRIFICES AND RITESfactsanddetails.com; RELIGIOUS TAOISM AND TAOIST TEMPLES AND RITUALSfactsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey” by Kenneth Ch'en Amazon.com; “Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China” by Christine Mollier Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; “China Root: Taoism, Ch'an, and Original Zen” by David Hinton Amazon.com; Buddhism Between Tibet and China” Matthew Kapstein Amazon.com; Buddhist Art: “The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com; “Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road” by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al. Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road” by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com

Chinese Buddhist Temple Architecture and Features

Fayuan main alter

“The temples at which most Chinese monks and lay Buddhists worshipped were made of wood, built to last at most a few centuries. Some were in the mountains, built for monks who wished to remove themselves from the clamor of everyday life. Lay Buddhists might make pilgrimages to these mountain temples, but there were also Buddhist temples much closer at hand in every town and city. There are no extant urban temple complexes dating from Tang times, though there are some in Japan that were based on Chinese models. “

Temples can be several stories high and often have steeply sloped roofs that are supported on elaborately-decorated and colorfully-painted eaves and brackets. The main shrines often contain a Buddha statue, boxes of sacred scriptures, alters with lit candles, burning incense and other offerings as well as images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and devas. The central images depends on the sect.

Buddhist temples usually have red pillars while Taoist temples have black ones. Just inside a Buddhist temple gates are statues or images of the Four Heavenly Kings of the Four Directions and Maitreya, the chubby laughing Buddha. The main hall features three large statues seated on lotus flowers: the Buddhas of the past, present and future. Behind them is often a statue of Guanyin, the multi-armed Goddess of Mercy.

Many temples are funded by donations with large amounts of money for prestigious temples coming from Buddhists in Hong Kong and Taiwan and elsewhere around the world. Some Chinese Buddhist temples invite Tibetan monks in an effort to attract to more followers.

See Buddhism

Fayuan Temple in Beijing: an Example of an Urban Chinese Buddhist Temple

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: Fayuan Temple (Dharma Origin) in Beijing was first completed in the late seventh century during the Tang. Over the last thousand plus years, the temple was destroyed by warfare, fire, and even an earthquake. Thus it has had to be rebuilt many times, and most of its surviving buildings date to the seventeenth-nineteenth centuries. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Worshipers enter through the main gate. The side buildings are of secondary importance. They include halls to patron saints, halls to remember loved ones and temple offices. The next layer out is made up of buildings used by monks and nuns rather than lay people. There are dormitories, study halls, and dining halls for those who live in the temple. /=\

The main gate is also called the mountain gate. Looking inside we see an incense burner set before the first central building and a pair of lions guarding the door, which are common to many kinds of buildings in China, not just Buddhist temples. Passing through the gate we glance to our right and left and see the drum and bell towers respectively. As the name implies, the drum tower houses a large drum and the bell tower, a bell. /=\

The central buildings are ones of primary importance. They house the shrines to Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other deities as well as scriptures and holy relics. The characters over the door in the he first central building tell us it is the hall of the Divine Kings, the guardians of this temple. These temple buildings are good examples of traditional Chinese architecture. Even today there are attempts to incorporate elements of traditional Chinese architecture into new temple buildings. /=\

The main altar in the Main Hall is on the left side as you enter. A gilded Buddha statue almost four meters tall stands in the center, flanked by two other figures. In front of them are a ceremonial incense burner, candles, a vase of flowers, and plates with offerings of fruit. Further back in the temple compound we find the building that houses the Buddhist scriptures. /=\

Mt. Wutai embraces a sprawling complex of temples that house some of China's oldest Buddhist manuscripts. Its 53 monasteries house hundreds of monks and nuns. More than 150 temples, many just ruins, are scattered on terraced hillsides and remote mountain tops. The oldest temples dates back to the A.D. first century, when Buddhism arrived in China from India. The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Shuxian Temple is a huge complex with 500 statues of Buddhist figures set among mountains and streams. Xiangtong Temple (A.D. 75), Foguang Temple A.D. 857), with life size clay sculptures, and Nanchan Temple (A.D. 782) are among China's oldest temples.

According to UNESCO: “ The cultural landscape is home to forty-one monasteries and includes the East Main Hall of Foguang Temple, the highest surviving timber building of the Tang Dynasty (618-906), with life-size clay sculptures. It also features the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Shuxiang Temple with a huge complex with 500 ‘suspension’ statues representing Buddhist stories woven into three-dimensional pictures of mountains and water. Overall, the buildings on the site catalogue the way in which Buddhist architecture developed and influenced palace building in China for over a millennium. [Source: UNESCO]

“Two millennia of temple building have delivered an assembly of temples that present a catalogue of the way Buddhist architecture developed and influenced palace building over a wide part of China and part of Asia. For a thousand years from the Northern Wei period (471-499) nine Emperors made 18 pilgrimages to pay tribute to the bodhisattvas, commemorated in stele and inscriptions. Started by the Emperors, the tradition of pilgrimage to the five peaks is still very much alive. With the extensive library of books collected by Emperors and scholars, the monasteries of Mount Wutai remain an important repository of Buddhist culture, and attract pilgrims from across a wide part of Asia.

Wutaishan is special because: 1) The overall religious temple landscape of Mount Wutai, with its Buddhist architecture, statues and pagodas reflects a profound interchange of ideas, in terms of the way the mountain became a sacred Buddhist place, endowed with temples that reflected ideas from Nepal and Mongolia and which then influenced Buddhist temples across China. 2) Mount Wutai is an exceptional testimony to the cultural tradition of religious mountains that are developed with monasteries. It became the focus of pilgrimages from across a wide area of Asia, a cultural tradition that is still living. 3) The landscape and building ensemble of Mount Wutai as a whole illustrates the exceptional effect of imperial patronage over a 1,000 years in the way the mountain landscape was adorned with buildings, statuary, paintings and steles to celebrate its sanctity for Buddhists. 4) Mount Wutai reflects perfectly the fusion between the natural landscape and Buddhist culture, religious belief in the natural landscape and Chinese philosophical thinking on the harmony between man and nature. The mountain has had far-reaching influence: mountains similar to Wutai were named after it in Korea and Japan, and also in other parts of China such as Gansu, Shanxi, Hebei and Guandong provinces.

Fawang Temple, second oldest Buddhist temple in China

Foguang Temple (Temple of Buddha’s Light)

Foguang Temple (five kilometres from Doucun, Wutai County,100 kilometers north-northwest of Taiyuan, 150 kilometers south of Datong) is a remarkable wooden Buddhist temple with large intact parts that back to Tang Dynasty (618–907). The major hall of the temple, the Great East Hall, was built in 857. According to architectural records, it is the third earliest preserved timber structure in China. It was rediscovered by the 20th-century architectural historian Liang Sicheng (1901–1972) in 1937. The temple also contains another significant hall dating from 1137 called the Manjusri Hall. In addition, the second oldest existing pagoda in China (after the Songyue Pagoda), dating from the 6th century, is located in the temple grounds. Today the temple is part of the Mount Wutai UNESCO World Heritage site and is undergoing restoration.

The famous Communist-era intellectuals and preservation advocates Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng found Foguabg after a great deal of searching. Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Their dream had always been to find a wooden temple from the golden age of Chinese art, the glorious Tang Dynasty (618-906). It had always rankled them that Japan claimed the oldest structures in the East, although there were references to far more ancient temples in China. But after years of searching, the likelihood of finding a wooden building that had survived 11 centuries of wars, periodic religious persecutions, vandalism, decay and accidents had begun to seem fantastical. (“After all, a spark of incense could bring down an entire temple,” Liang fretted.) In June 1937, Liang and Lin set off hopefully into the sacred Buddhist mountain range of Wutai Shan, traveling by mule along serpentine tracks into the most verdant pocket of Shanxi, this time accompanied by a young scholar named Mo Zongjiang. The group hoped that, while the most famous Tang structures had probably been rebuilt many times over, those on the less-visited fringes might have endured in obscurity. [Source: Tony Perrottet; Smithsonian Magazine, January 2017]

“The actual discovery must have had a cinematic quality. On the third day, they spotted a low temple on a crest, surrounded by pine trees and caught in the last rays of sun. It was called Foguang Si, the Temple of Buddha’s Light. As the monks led them through the courtyard to the East Hall, Liang and Lin’s excitement mounted: A glance at the eaves revealed its antiquity. “But could it be older than the oldest wooden structure we had yet found?” Liang later wrote breathlessly.

“In the morning, I haggled with a driver to take me the last 23 miles to the Temple of Buddha’s Light. It is another small miracle that the Red Guards never made it to this lost valley, leaving the temple in much the same condition as when Liang and Lin stumbled here dust-covered on their mule litters. I found it, just as they had, bathed in crystalline sunshine among the pine trees. Across an immaculately swept courtyard, near-vertical stone stairs led up to the East Hall. At the top, I turned around and saw that the view across the mountain ranges had been totally untouched by the modern age.

“In 1937, when monks heaved open the enormous wooden portals, the pair was struck by a powerful stench: The temple’s roof was covered by thousands of bats, looking, according to Liang, “like a thick spread of caviar.” The travelers gazed in rapture as they took in the Tang murals and statues that rose “like an enchanted deified forest.” But most exciting were the designs of the roof, whose intricate trusses were in the distinctive Tang style: Here was a concrete example of a style hitherto known only from paintings and literary descriptions, and whose manner of construction historians could previously only guess. Liang and Lin crawled over a layer of decaying bat corpses beneath the ceiling. They were so excited to document details such as the “crescent-moon beam,” they didn’t notice the hundreds of insect bites until later. Their most euphoric moment came when Lin Huiyin spotted lines of ink calligraphy on a rafter, and the date “The 11th year of Ta-chung, Tang Dynasty (618-906)” — A.D. 857 by the Western calendar, confirming that this was the oldest wooden building ever found in China. (An older temple would be found nearby in the 1950s, but it was far more humble.) Liang raved: “The importance and unexpectedness of our find made this the happiest hours of my years of hunting for ancient architecture.” Today, the bats have been cleared out, but the temple still has a powerful ammonia reek — the new residents being feral cats.

Fayuan Temple layout

Nanchan Temple

Nanchan Temple (near Doucun on Mt. Wutai, 100 kilometers north-northwest of Taiyuan, 150 kilometers south of Datong) is a Buddhist temple. Its Great Buddha Hall, built in 782 during the Tang Dynasty, is China's oldest preserved wooden building. Not only is it important architecturally it also contains an original set of artistically-important Tang sculptures dating from the period of its construction. Seventeen sculptures share the hall's interior space with a small stone pagoda. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Great Buddha Hall of Nanchan Temple has been dated based on an inscription on a beam. It has endured and escaped destruction during the late Tang Dynasty Buddhist purges of 845, perhaps due to its isolated location in the mountains. Another inscription on a beam indicates that the hall was renovated in 1086 of the Song Dynasty, at which time all but four of the original square columns were replaced with round columns. In the 1950s the building was rediscovered by architectural historians, and in 1961 it was recognized as China's oldest standing timber-frame building. Just five years later in 1966, the building was damaged in an earthquake, and during the renovation period in the 1970s, historians carefully studied the structure piece by piece.

The Great Buddha Hall is a humble timber building with massive overhanging eaves and a three bay square hall that is 10 meters deep and 11.75 meters across the front. The roof is supported by twelve pillars that are implanted directly into a brick foundation. The hip-gable roof is supported by five-puzuo brackets. The hall does not contain any interior columns or a ceiling, nor are there any struts supporting the roof in between the columns. All of these features indicate that this is a low-status structure. The hall contains several features of Tang Dynasty halls, including its longer central front bay, the use of camel-hump braces, and the presence of a yuetai.

Nanchan Temple and nearby Foguang Temple contains original sculptures dating from the Tang Dynasty. The hall contains seventeen statues and are lined up on an inverted U-shaped dais. The largest statue is of Sakyamuni, placed in the center of the hall sitting cross-legged on a sumeru throne adorned with sculpted images of a lion and demigod. Above the large halo behind the statue are sculpted representations of lotus flowers, celestial beings and mythical birds. Flanking him on each side are attendant Bodhisattvas with a knee placed on a lotus. A large statue of Samantabhadra riding an elephant is at the far left of the hall and a large statue of Manjusri riding a lion is on the far left. There are also statues of two of Sakyamuni's disciples (Ananda and Mahakashyapa), two statues of heavenly kings and four statues of attendants.

The Great Buddha Hall also contains one small carved stone pagoda that is five levels high. The first level is carved with a story about the Buddha, and each corner contains an additional small pagoda. Each side of the second level is carved with one large Buddha in the center, flanked with four smaller Buddhas on each side. The upper three levels have three carved Buddhas on each side.

Chinese Buddhist Temples Activities and Acts of Worship

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Common forms of Buddhist practice for lay persons include visiting temples to pray, burn incense, place offerings of fruit or flowers at altars, and observe rituals performed by monks, such as the consecration of new images or the celebration of a Buddhist festival. Buddhist women's association meet for worship. Ceremonies at tenmples are held for things like the enshrinement of an image of a wealthy patron. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Joss sticks (incense sticks) have traditionally been an important component of Taoist religious practice. Worshippers believe the smoke helps waft prayers towards their deities. Today the sticks are also fixtures of Confucian and Buddhist worship. Sometimes they are even part of Christian rituals. Worshippers normally light three joss sticks in the courtyard of the house of worship, and place them in sand-filled containers or in specially prepared racks. [Source: The Religions of South Vietnam in Faith and Fact, US Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Chaplains Division,1967 ++]

Joss sticks and incense burners are found in family altars, spirit houses, and temple courtyards and before the figures of Buddha. Not all joss sticks are fragrant as some are primarily for smoke and have only the faintest odor. However, the more favored joss sticks are the ones with incense which serves both as a means of veneration and as a practical deodorizer. Few homes are without a joss stick to be utilized for some reason. Traditionally, joss sticks have been handmade. Basically the joss stick is made with a thin bamboo stick, which is painted red, Part of the stick is rolled in a putty-like substance-the exact formulae are guarded by their owners. ++

Joss sticks are very reasonably priced, and it is good for the common people that this is so, for few acts of devotion could be complete without the lighting of joss sticks. These may be placed in sand-filled containers either in the temple courtyard or in racks located in front or on top of an altar. Sometimes after burning joss sticks are placed in front of a Buddha statue, the ascending smoke from the burning joss stick is thought by some to have beneficial aid in pleasing that power to whom worship is made, or prayers offered. ++

Taoist-Buddhist Funeral

Funerals in China often have Buddhist elements. On the funeral for his grandfather on his mother's side: Chihoung Chen told his son Leon Chen: When we went back that time, we didn't know much about funerals, so we had other people who worked for the funeral home perform the procedures. They cleaned his body and changed his clothes. They asked us if we had any money. We gave them some money. The people working for the funeral home took the money and put it in your grandfathers's hand, then gave it to us. They said that your grandfather gave the money to us, and they wanted us to keep it forever. Then we invited Buddhist monks, and they chanted sutras. [Source: interview of Chihoung Chen conducted by his son, Leon Chen; Freer Gallery of Art asia.si.edu ^^]

Funerals in China often have Buddhist elements. On the funeral for his grandfather on his mother's side: Chihoung Chen told his son Leon Chen: When we went back that time, we didn't know much about funerals, so we had other people who worked for the funeral home perform the procedures. They cleaned his body and changed his clothes. They asked us if we had any money. We gave them some money. The people working for the funeral home took the money and put it in your grandfathers's hand, then gave it to us. They said that your grandfather gave the money to us, and they wanted us to keep it forever. Then we invited Buddhist monks, and they chanted sutras. [Source: interview of Chihoung Chen conducted by his son, Leon Chen; Freer Gallery of Art asia.si.edu ^^]

“This funeral was a combination of Taoism and Buddhism. After that the coffin was closed. A lot of people sent flowers. Your grandfather was the second most powerful general in the Taiwan navy. And then we went to the mountains. Traditionally, we would throw paper, but your grandmother was a principal of an elementary school, so we didn't throw that much as to not harm the environment. At the grave site, we waited. Chinese people believe that there must be a certain time for burial. It's all determined by a feng-shui master. He determines the time and the day and the angle. He has a special kind of compass and waited for the right time. I have one of those instruments. ^^

“Afterwards, we were grateful to those workers so we took them out to dinner. After several years, many people in Taiwan go back and collect the bones. It's not that popular among mainland Chinese, but it's done very often in Taiwan. After awhile, they go back and open up the coffin. The bones are then placed as to resemble the skeleton and they would spray wine on it. Some people would cremate the bones, while others would clean it, spray it with wine again, and put it into the coffin. The Chinese say that the more the body decomposed the better. If the body is not decomposed, then it's bad luck. It means the soul isn't willing to leave the body. Egyptians in old days want bodies to stay whole. In some cases, if the body can't be found, then clothes or a paper with their Sign would be placed in the coffin. If there's like a car crash and a person's in a coma, then people would take clothes and incense and call the soul back. ^^

“Sometimes there are two coffins. The body is placed in a coffin, then that coffin is placed inside a bigger coffin. Chinese beliefs are different from those of other cultures....In the past, there were shops with the body parts of the portraits all painted in. Once somebody died, family members would go to the shop and commission a painting and the artist would paint the head in. Nowadays, there are no ancestral halls to place the portraits. Your grandparents probably saw them.” Do you think there are any more of those shops you were talking about? “No. First of all, the houses were too small, and the Cultural Revolution probably destroyed them. The Communists also dug up many graves, including those of your great-great grandfather and the great grandfather on your grandmother's side. Many graves were dug.” ^^

Chinese Buddhist Monks

Enshrinment ceremony

Chinese Buddhist monks often have have shaved heads and wear grey robes. Activities include praying and chanting at temples, presiding over funerals, leading a religious services, reciting sutras, meditating and doing various chores around their temples and monasteries. Monks at Shaolin sometimes pray and meditate while handing upside down from their feet in a tree branch. See Shaolin Temple Under Martial Arts and Places.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Following the Buddha and the Dharma (teaching), the community of Buddhist monks and nuns, or sangha, constitute the third of the Threefold Refuge, a basic creed of Buddhism. Their behavior is strictly disciplined by the sacred canon. These monks and nuns adopt distinctive styles of appearance and behavior. There is an incredible diversity existing among various schools of Buddhism. In addition, customs and rituals continue to evolve. Today, greater ease of travel has facilitated international exchange for monks and nuns. Monks travel to do things like attend a ceremony to celebrate the commemoration of a stele inscription. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Traditionally, children often joined monasteries and nunneries because their parents gave them to the church to fulfill a religious vow. These children lived within the monastery until they were able to become novices and prepare for their ordination. Music and sound are important aspects of life in a Buddhist monastery. Bells, cymbals and other percussive instruments signal transitions between daily activities. They also accompany sessions of chanting that have a singing quality. These chants produce a distinctive, impressive sound and can last for hours.” /=\

Monks in Shanghai are learning foreign languages, improving their computer skills and taking classes in financial management as part of their effort to keep Buddhism modern and relevant. A monk at Shanghai's Jade Buddha Temple told the Los Angeles Times, ‘some people think monks should do nothing but sit around and read scriptures. The times have changed — we have to change too, If we stay the same, we can't survive." Another monk at the Jade Buddha Temple told Reuters, “The first thing I do in my daily work is open the laptop and check e-mails and surf the Internet. Everything in the temple is now processed online. No paperwork. Those who failed the computer test were laid off and reassigned nonoffice jobs."

Describing the routine at Jade Buddha Temple he said, “We are very busy, no weekends or vacation. Interacting with the outside world occupies most our time, so many monks have to use the noon break if they want to do meditation...Before everyone including the abbot had to clean the temple, and old monks were assigned to check tickets and guard the temple. But they often smoked and fell asleep, causing bad influences, Now we have hired professional service companies to be responsible for temple security and cleaning. This works very well."

Arthur Henderson Smith, an American missionary, wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894: “The whole body of Buddhist and Taoist priests in China is an organized army of parasites. Their stock in trade is the irrepressible human instinct of worship, and by means of this alone, they are able to persuade the shrewd and practical Chinese to support the priests in such ease and comparative luxury as but a small proportion of the population are able to attain. In addition to receiving the income from the land which is given to the temples, afterthe wheat and autumn harvests, the priests go about levying their tax, on every family in the village, a tax consisting of a greater or less contribution in grain, the refusal of which would certainly lead to dramatic consequences. Besides this, each priest is well paid in food and in money for his services at the temples on special days, or at funerals. Taking into consideration the industry and the economy of the Chinese people, and contrasting these characteristics with the phenomena exhibited in the lives of the priest, it is not strange that a poet has said "The sun ishigh on the mountain monastery, but the priest is not yet up; from this we see that fame and gain are not equal to indolence." [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

Zhao Defa's Book on Buddhist Monks

Han Bingbin wrote in the China Daily, “Suffering hardships while growing up in rural Shandong province in the 1950s and 60s, writer Zhao Defa rose to fame because of his self-inspired and thought-provoking countryside trilogy that forcefully delves into the intertwining relations of land, rural ethics and politics.But as a professional writer, for a long time he embarrassedly found himself unable to find a new field of writing that's out of his experiences yet inspires equally profound thinking. [Source: Han Bingbin, China Daily, October 8, 2013 ]

“One day in 2003 he was approached by the abbot of a local temple to give a cultural talk. While the humble writer prepared himself by glancing over a few books on Buddhism, it soon occurred to him religion is exactly the topic that arouses both his curiosity and intellectual hunger. He immediately pinned down his next book, a non-fictional exploration into the survival of Chinese Buddhism in modern-day society, to be wrapped up in a fictional storyline.

“In the following four years, he lived in nearly all of China's major Buddhist temples. While closely observing the lives of various monks, he bore his questions in mind: How do these monks fight against their own worldly desires? How has constant social transformation impacted Buddhism? In his book “Shuangshou Heshi” (Praying Hands), readers will find their own answers to these questions by following the life of Huiyu, a fictional protagonist who went through many struggles against obstacles from both within himself and the outside world to finally be enlightened to create his own way of practicing Zen.

"How to face the suffering? How to use Buddhism doctrine to instruct life and purify the heart? That's what some responsible monks have been doing these days," the author says. "In my book, there are also portraits of those who try to make a fortune using Buddhism, a sign of how social transformation has caused disturbance within religion. The meaning of life is being questioned in both the monks' and the laymen's world."

“Literature critic He Shaojun says the book, even though with a new theme, has actually carried on Zhao's constant reflections on moral principles in social changes by exploring how Buddhist culture interacts with modern ethics. Beijing Normal University's Chinese literature professor Zhang Qinghua says just like how Zhao acutely detected the disappearing of land and rural civilization during industrialization, the author has again demonstrated his admirable sensitivity to social and cultural changes.

“Given what he has achieved today, the interesting question people often throw at Zhao is this: If he had met Buddhism much earlier in his life when he still suffered enormously, would he have converted? "It's hard to say. Even after learning so much about Buddhism, I'm not converted. I understand some of the teachings. But for some others I don't fully understand and accept. I studied it as a cultural phenomenon," he says. "Huiyu is of course an ideal character. I am still very much a secular person in real life. "My wife used to wonder why I wrote something like this without even having talked to any monk before. I said perhaps I was a monk in my previous life."

Buddhism and Sexuality in China

Nuns at Kaifu nunnery in Changsa, Hunan

Most Buddhist schools denied sexual desire, and traditionally Buddhist monks have been celibate. But, it is not the case of the school of Mi-tsung (Mantrayana, or Tantrism). Sex was the major subject of Mi-tsung. Mi-tsung was very similar with some sects of Taoism, and stressed the sexual union. Even Mi-tsung said that Buddhatvam yosidyonisamas-ritam (“Buddheity is in the female generative organs”). In China, “ Tibetan Esoteric Sect” (Tibetan Mi-tsung) flourished in the Yuan Dynasty, especially from the time of Kubilai Khan (A.D. 1216-1294). Women call their vagina the “yoni” and invoked “Tantric practitioners”. [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D. Encyclopedia of Sexuality hu-berlin.de/sexology =]

According to the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: Through Buddhist-nun monasteries, Buddhism exerted a strong influence for the equality of men and women. Although the monasteries were skeptically regarded by the Confucianist elite - one of the common defamations being that the nuns were involved in lesbian sexual practices - Buddhism gave women another role model besides that of wife and mother. This was especially true for elderly widows who were entering Buddhist orders. On the other hand, their influence on the priesthood seems to be difficult to detect. [Source: Encyclopedia of Sexuality, 1997 2.hu-berlin.de/sexology */ ]

Buddhist Abbot at Well-Known Beijing Temple Accused of Sexually Abusing Nuns

In 2018, Venerable Master Xuecheng, a Buddhist monk and president of the Chinese Buddhist Association, was accused of seducing a number female nuns by convincing them of “purification” through physical contact. Jiayun Feng wrote in SupChina: “The abbot of Longquan Temple in Beijing, Xuecheng is the latest public figure to be accused of sexual misconduct in China. The “Venerable Master” of Longquan, one of the highest-profiled monasteries in the country, has called the allegations “false” and “misleading.” “Xuecheng is president of the Chinese Buddhist Association — the youngest person to ever hold an executive post in the administration — as well as a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. [Source: Jiayun Feng, SupChina, August 1, 2018]

In a 95-page expose titled “Report on important matters,” which was shared on WeChat on July 31 and instantly went viral, two former masters at Longquan Temple, Xianjia and Xianqi , said Xuecheng has been preying on bhikkhunis (ordained female monastics) for years, specifically that he has had sex with multiple nuns by persuading them they could be “purified” through physical contact. (Celibacy is one of the tenets of Buddhist monasticism.) Included in the document are extensive records of explicit text messages sent by Xuecheng, showing how he emotionally manipulated his victims by denying them communication with the outside world, and a personal essay written by bhikkhuni Xianjia, one of Xuecheng’s alleged victims, who says that during her two-month stay at Longquan in 2018, Xuecheng kept sending her messages containing vulgar language and making unwanted advances on her. “My belief system almost collapsed,” Xianjia writes. “I even considered giving up Buddhism and returning to secular life.”

Xuecheng issued a formal denial (in Chinese) on Weibo. Signed by the temple, the article accuses the two former masters, Xianjia and Xianqi, of “collecting and fabricating material, distorting facts, spreading false reports, defaming the great virtue of Buddhism, and misleading the public.” The statement says the temple is seeking legal action against the accusers and asks relevant departments to open an investigation into the case, and to consider the complicity of a group of “ill-intended individuals who attempted to damage the reputation of Xuecheng and Longquan.” The denial left many Chinese internet users unconvinced. “Compared to the expose, which is about 100 pages long and reads like a well-argued doctoral dissertation with abundant evidence, this one feels flimsy,” one Weibo user wrote (in Chinese).Meanwhile, on WeChat, where the case first attracted attention, the original document — which is in PDF form — has been banned from sharing.

Robot Monk Unveiled at Same Temple as the Highly-Sexed Abbot

In 2016, Reuters reported: “Longquan temple says it has developed a robot monk that can chant Buddhist mantras, move via voice command, and hold a simple conversation. Named Xian’er, the 60-cm (2-foot) tall robot resembles a cartoon-like novice monk in yellow robes with a shaven head, holding a touch screen on his chest. Xian’er can hold a conversation by answering about 20 simple questions about Buddhism and daily life, listed on his screen, and perform seven types of motions on his wheels. [Source: Reuters, April 24, 2016]

“Master Xianfan, Xian’er’s creator, said the robot monk was the perfect vessel for spreading the wisdom of Buddhism in China, through the fusion of science and Buddhism. “Science and Buddhism are not opposing nor contradicting, and can be combined and mutually compatible,” said Xianfan.

“Xianfan said Buddhism filled a gap for people in a fast-changing, smart-phone dominated society. “Buddhism is something that attaches much importance to inner heart, and pays attention to the individual’s spiritual world,” he said. “It is a kind of elevated culture. Speaking from this perspective, I think it can satisfy the needs of many people.”

“The little robot monk was developed as a joint project between a technology company and artificial intelligence experts from some of China’s top universities. It was unveiled to the public in October, 2015. But Xian’er is not necessarily the social butterfly many believe him to be. He has toured several robotics and innovation fairs across China but rarely makes public appearances at Longquan temple.

“Xian’er spends most of his days “meditating” on a shelf in an office, even though curiosity about him has exploded on social media. Xian’er was inspired by Xianfan’s 2013 cartoon creation of the same name. The temple has produced cartoon animations, published comic anthologies, and even merchandise featuring the cartoon monk. Michelle Yu, a tourist and practicing Buddhist, said she first spotted Xian’er on social media. “He looks really cute and adorable. He’ll spread Buddhism to more people, since they will think he’s very interesting, and will make them really want to understand Buddhism,” she said. The temple is developing a new model of Xian’er, which it says will have a more diverse range of functions.

Revered Chinese Monk Is Mummified and Covered in Gold Leaf

mummified monk

In 2016 it was announced that a revered Buddhist monk in China had been mummified and covered in gold leaf, a practice reserved for holy men in some areas with strong Buddhist traditions. Associated Press reported: “The monk, Fu Hou, who died in 2012 at age 94 after spending most of his life at the Chongfu Temple on a hill in the city of Quanzhou, in southeastern China, according to the temple's abbot, Li Ren. [Source: Didi Tang, Associated Press, April 28, 2016]

“The temple decided to mummify Fu Hou to commemorate his devotion to Buddhism — he started practicing at age 17 — and to serve as an inspiration for followers of the religion that was brought from the Indian subcontinent roughly 2,000 years ago. Immediately following his death, the monk's body was washed, treated by two mummification experts, and sealed inside a large pottery jar in a sitting position, the abbot said.

“When the jar was opened three years later, the monk's body was found intact and sitting upright with little sign of deterioration apart from the skin having dried out, Li Ren said. The body was then washed with alcohol and covered in layers of gauze, lacquer and finally gold leaf. It was also robed, and a local media report said a glass case had been ordered for the statue, which will be protected with an anti-theft device. The local Buddhist belief is that only a truly virtuous monk's body would remain intact after being mummified, local media reports said. "Monk Fu Hou is now being placed on the mountain for people to worship," Li Ren said.

Image Sources: Monks, Harvard Education; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021