BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA

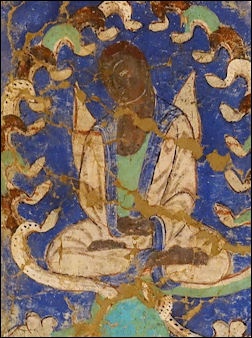

5th century painting of Monk Ajnatakaundinya from Kizil Caves

The most well known sculptures to come out of China are the images of Buddhas found in caves and sculptures unearthed from tombs. Art from India and Central Asia made its way into China in great amounts between the A.D. 1st and 5th centuries. During this period Buddhist art was created on the cave walls of Yungang.

As Buddhism, took root in China, it became a major cultural force, inspiring some of China's most brilliant paintings and sculptures. The periods of Chinese Buddhist art closely parallel the phases the Buddhist religion was going through in China . Works that appeared in the 5th and 6th centuries were very free and individualistic. In the Tang period the art became more mature and robust, with Buddhist figures featuring graceful lines and curves. In the 10th to 13th century it became more refined. After that it was rooted in tradition and lacked innovation.

Buddhists filled caves throughout China with sculptures and murals. In the cliffs of the Tian Shan mountains in the Kumtura and Kizil regions of Xinjiang province in western China, for example, there are hundreds of caves adorned with Buddhist painting that date as far back as the A.D. 5th century. Scholars believe the paintings — many depicting episodes from the lives of the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, painted using paint made from ground minerals such as malachite for green and iron oxide for red — were commissioned by lay people and painted by local artists

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Buddhism brought to China a large range of divine beings, all of whom came to be depicted in images at temples, either on their walls or as free standing statues. The earliest Buddhist images in China owed much to traditions developed in Central Asia, but over time Chinese artists developed their own styles. Here we look separately at the evolution of the different divine beings in the Buddhist pantheon, then look briefly at groupings of deities.” [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

See Separate Article BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Buddhism in China Buddhist Studies buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in China Wikipedia Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Buddhist Art: Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn ; Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Buddhist Artwork buddhanet.net/budart/index ;Buddhism and Buddhist Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Buddhist Art Huntington Archives Buddhist Art dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart ; Buddhist Art, Smithsonian freersackler.si.edu; Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; Mahayana Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ; The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ; Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ; Chinese Religion and Philosophy: Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LOTUS SUTRA AND THE DEFENSE OF BUDDHISM AGAINST CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com; CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES, MONKS AND FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHISM TODAY factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM VERSUS THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road”

by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al.

Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road”

by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com;

“How to Read Buddhist Art” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art - How to Read)

by Kurt A. Behrendt Amazon.com ;

“Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols” by Meher McArthur Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art: An Historical and Cultural Journey” by Giles Beguin Amazon.com ;

“Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India” by John Guy Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art” by Adriana Proser, Susan Beningson Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art and Architecture” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Architecture” by Le Huu Phuoc Amazon.com ;

“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com;

“The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon” by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com

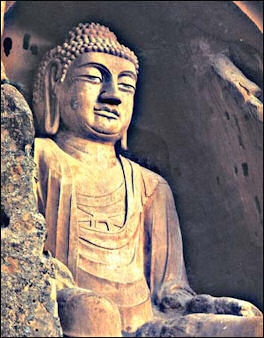

Subjects and Gestures in Chinese Buddhist Art

In Chinese images, The Buddha usually has a raised bump on the top of his head (usnisa), raised dot in the middle of the forehead (urna), a luminous tuft of hair between the eyebrows, robe-like clothing on the body without ornaments and a nimbus behind his back. Often he is seated in a stand made of lotus flower pedals and depicted with other common conventions such as elongated ears. These features refer to the life story of the historical Buddha. For example, the long earlobes remind one of the heavy ear ornaments the Buddha would have worn while still living in the palace. [Sources: Shanghai Museum Education Department; Metropolitan Museum of Art]

5th century Buddha at Mt. Xumi

Bodhisattvas are Buddha-like beings that spread Buddhism and help human being strive towards enlightenment. Indian Bodhisattvas were typically more masculine while Chinese Bodhisattvas become more feminized as they were merged with Chinese goddesses of mercy. Most Chinese Bodhisattvas are clothes in elaborate and elegant clothing. Arhat were the followers or disciples of The Buddhas. They are typically ascetic, monk-like figures. There are different ones with their own names and characteristics.

Heavenly Guardians (Lokapala in Chinese) began as the four ancient Indian mythological guardians and evolved into Buddhist protector deities, protecting the Buddhist doctrines in the four directions. They usually appear with body armor and a sword in one hand. In modern Chinese Buddhist temples the four guardians respectively hold a 1) a sword; 2) a pipa (plucked string instrument), 3) an umbrella and 4) a snake, symbols of favorable weather.

Among the gestures (mudra) commonly seen in Chinese Buddhist sculptures and art are: 1) The thumb on the middle finger means expounding the doctrine and knowledge. 2) The Abhaya mudra with the hand held up so the palm faces the viewer is a sign of protection and assurance, no fear. 3) The Vara mudra with hand held down so the palm faces the viewer is a sign of fulfilling vows and granting favors; 4) Mudra of appeasement; 5) Mudra of humility, touching the ground; 6) Diamond handclasp mudra; 7) Mudra of concentration; and 8) Mudra of turning the wheel of the law.

There are two ways of sitting cross-legged. One way is with soles of both feet facing upwards — the Lotus position — usually seen on statues of the Buddha. The other way is with one foot sole facing upwards, usually seen on statues of Bodhisattvas.

History of Chinese Buddhist Art

Denise Leidy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ Long-lasting encounters between Indian and Chinese Buddhism and the beliefs, practices, and imagery associated with their respective traditions remains one of the most fascinating in world history... Over time, Buddhism expanded from its initial focus on the Historical Buddha Shakyamuni to include numerous celestial Buddhas as well as bodhisattvas and other teachers and protectors. Buddhas are understood as beings that have achieved a state of complete spiritual enlightenment and are no longer constrained by the phenomenal world. Bodhisattvas, who are also enlightened, choose to remain accessible to others. In China, two of the most important bodhisattvas are Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin), the embodiment of the virtue of compassion, and Manjushri (Wenshu), the personification of profound spiritual wisdom. By the tenth century, both were understood to be able to manifest in a range of forms; Avalokiteshvara sometimes took the form of a woman, which helps to explain the early Western perception of this divinity as female. [Source:Denise Leidy, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

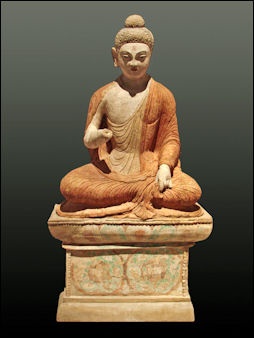

Tang-era clay Buddha statue from Bingling Temple in Gansu Province

“Buddhism may have been known in China as early as the second century B.C., and centers with foreign monks, who served as teachers and translators, were established in China by the second century A.D. Early representations of Buddhas are sometimes found in tombs dating to the second and third century; however, there is little evidence for widespread production and use of images until the fourth century, when a divided China, particularly the north, was often under the control of non–Han Chinese individuals from Central Asia. In addition to freestanding sculptures, numerous images were also carved in cave-temples at sites such as Dunhuang, Yungang, and Longmen. Also found in India and Central Asia, these man-made cave-temples range from simple chambers to enormous complexes that include living quarters for monks and visitors. \^/

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ Literally, the term "Buddha" means "enlightened one." According to Buddhist beliefs, however, there have been innumerable Buddhas over the eons. This section will look primarily at Sakyamuni, the historical founder of Buddhism. Sakyamuni was born around 500 B.C. in north India. As a young man, unsatisfied with his life of comfort and troubled by the suffering he saw around him, he left home to pursue spiritual goals. After trying a life of extreme asceticism, he found enlightenment while meditating under a tree. For the next forty-five years, he traveled through north India, preaching, attracting followers, and refuting adversaries. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

By the time Buddhism reached China, images of the Buddha played a major role in devotional practices. As you will see, the Buddha is usually depicted as austere in stature, pose, and dress. Otherworldly features are highlighted while human characteristics are de-emphasized. Mudras, or gestures performed with the hand, convey various actions. /=\

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Buddha was originally distinguished by thirty-two special marks of perfection (mah purusa laksana) including a golden body. Therefore, images made of wood, molded clay, and stone are all customarily gold gilt, whereby the Buddha's perfection is compared to infinite rays of light. According to the Buddhist sutras, "A gold-colored body is one of the thirty-two favorable marks of the Buddha- The golden rays shine upon the Twenty Eight Heavens, the Eighteen Hells, and the world of the Buddhist deities (from T'ai-tzu jui-ying pen-ch'i ching). The Buddha's golden hue is marvelous, ethereal (from The Sutra of Cause and Effect, Past and Present).” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Early Buddhist bronzes preserve distinctive foreign characteristics, such as the emaciated face and deep-set features of a seated Buddha from the fifth century. Early examples of Buddhist sculpture in China showed a greater Central Asian influence. Examples of this are seated Buddhas carved into stone cliff during the Northern Wei period (A.D. 386 to 534) and standing stone Buddhas in the cave temple complex at Maijishan, which dates to the Western Wei period (A.D. 535 to 556).

Bodhisattvas in Chinese Art

5th century stone Bodhisattva from Maijishan

“The period from the fourth to the tenth century was marked by the development and flowering of Chinese traditions such as Pure Land, which focuses on the Buddha Amitabha and the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and Chan (or Zen). Pure Land practices stress devotion and faith as a means to enlightenment, while Chan features meditation and mindfulness during daily activities; both traditions are also prevalent in Korea and Japan. In addition, after the eight century, new Indic and Central Asian practices were also found in China. These included devotion to the celestial Buddha Vairocana, new and powerful manifestations of bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, and the use of cosmic diagrams such as mandalas. Many of these practices (best known today in some Japanese traditions and in Tibet) were intended to protect the nation and offer tangible benefits, such as health and wealth, to the ruling elite. Others involved complex rituals and forms of devotion designed for advanced practitioners. \^/

“Chinese Buddhist sculpture frequently illustrates interchanges between China and other Buddhist centers. Works with powerful physiques and thin clothing derive from Indian prototypes, while sculptures that feature thin bodies with thick clothing evince a Chinese idiom. Many mix these visual traditions. After the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when Buddhism disappeared from India, China and related centers in Korea and Japan, as well as those in the Himalayas, served as focal points for the continuing development of practices and imagery.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Along with the growing secularization of Buddhism in the Sung Dynasty (960-1279), its relation to the imperial court became increasingly distant. From this period is a large figure of Sakyamuni wearing a flowing robe with a gentle and kind expression. A fusion of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism flourished in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), at which time the Ch'an and Pure Land Schools came to rise. A Ming figure of the Amitabha Buddha on display is remarkably straight and symmetrical, the folds in the robe are precise and conceptualized.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Buddhas in Chinese Art

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have put off entering paradise in order to help others attain enlightenment. There are many different Bodhisattvas, but the most famous in China is Avalokitesvara, known in Chinese as Guanyin. Bodhisattvas are usually depicted as less austere or inward than the Buddha. Renouncing their own salvation and immediate entrance into nirvana, they devote all their power and energy to saving suffering beings in this world. As the deity of compassion, Bodhisattvas are typically represented with precious jewelry, elegant garments and graceful postures. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Hui-hsia Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings embodying compassion. While possessing the wisdom of the Buddha, the bodhisattva postpones attainment of nirvana in order to assist mortals in need. Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, seated upon a lion, often appears with Samantabhadra, the Bodhisattva of Universal Benevolence, who has an elephant as a mount. [Source: Chen, Hui-hsia, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Early examples of bodhisattvas in Chinese art include a 142-centimeter-tall, 5th century clay statue from Maijishan from the Northern Wei period and a 127-centimeter-tall, 5th century stone relief of Bodhisattva from Yungang. The Tang dynasty ushered in a period of growth and prosperity, during which Buddhism flourished. Buddhist beliefs, temples, and art permeated almost all levels of Tang life. Surviving Buddhist sculpture reflects the wealth of the great Buddhist monasteries. Many of these sculptures were decorated with rich, painted colors, which have faded with time. /=\

5th century stone apsara from Yungang

Guanyin is a bodhisattva featured in many artworks. The image of Guanyin was traditionally depicted as a young Indian prince, but during the Tang the feminine characteristics of Guanyin became more prominent. After the Tang, the cult of Guanyin grew in popularity largely due to popular literature, folk stories, and artistic images. By the sixteenth century Guanyin had become a Chinese goddess figure. In some folk religions she had become independent from her Buddhist origins. /=\

Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “The most beloved and worshipped bodhisattva in China is Avalokitesvara (Chinese: Kuan-yin). In the Southern and Northern Dynasties (220-589), Kuan-yin is depicted carrying a lotus flower in one hand, signifying purification. Kuan-yin's other common attributes include a holy water bottle (kadika), a whisk, and a willow branch. The water bottle, an indispensable item in the tropical climate of India, symbolizes cleansing of the human heart and Kuan-yin's compassion bestowed upon all sentient beings. The whisk represents Kuan-yin's ability to disperse worries and trouble, while the willow symbolizes Kuan-yin's gentle nature. Kuan-yin of the High T'ang adopts feminine features. In the Middle and Late T'ang, Kuan-yin figures appear free and easy, sitting in a meditative pose with one leg folded and the other relaxed. The facial features of Sung Dynasty (960-1279) bodhisattva figures from the Ta-li Kingdom (Yunnan) reflect strong regional influences. Moreover, in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) a large variety of images emerged reflecting Kuan-yin's strong popular appeal. The image of Kuan-yin holding a child, widely-worshipped in supplication for children, is one example of the bodhisattva's deep penetration into the popular religious tradition.” \=/

Divinities in Chinese Buddhist Art

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ Within Buddhist temples, in addition to the Bodhisattvas, groups of other divine figures help to complete the Buddha's entourage. They venerate, protect, and support the Buddha in a hierarchical structure. In this section you will be introduced to some of the more common figures. These include divine kings, gods of strength, and apsaras. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

In Buddhist tradition, the divine kings were responsible for protecting the Buddha and his Law, the sanctuary, and the Buddhist congregation from dangers and threats of evil forces arising from the four cardinal directions of the compass. The Gods of Strength are wrathful deities who are often depicted as hyper masculine beings. Subordinate to the Divine Kings, they are responsible for fighting the evil forces of the world. /=\

Hui-hsia Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “Lokapala and Mahakala are the Guardian Deities of Buddhism. Gazing angrily, and wielding weapons, these menacing figures appear perpetually ready to engage in battle to protect the dharma. The guardian deities are often positioned at the entrances of front halls of temples, in order to protect the temple. [Source: Chen, Hui-hsia, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

In Buddhist traditions, apsaras are heavenly beings. In depictions of paradise they hover above the Buddha. Apsaras are often depicted as female. When they are depicted in three-dimensional forms they are almost always done in shallow relief and not as a free standing sculpture. Apsaras are most often depicted in shallow relief while the other divinities are more often produced as free standing three-dimensional figures. /=\

Most of the time, people viewed Buddhist images not individually, but in assemblages. This was true both on the altars of temples and in the shrines people had in their homes. In looking at assemblages of Buddhist figures, it is important to notice differences in size and relative placement. A typical grouping include two Buddhas flanked by two Bodhisattvas with two apsaras floating above and a teaching Buddha surrounded by similar figures. /=\

Images in Chinese Buddhist Temples

Buddha image in Fayuan temple's main altar

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Most Chinese encountered Buddhist images within Buddhist temples, which came to be constructed by the hundreds and thousands across China as Buddhism gained followers. Before the end of the fifth century there were reportedly more than 10,000 temples in China, north and south. Some were undoubtedly small, modest temples, but in the cities many were huge complexes with pagodas, Buddha halls, lecture halls, and eating and sleeping quarters for monks, all within walled compounds. These temple complexes provided a place for the faithful to come to pay homage to images of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and meet with clergy. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

The best evidence of the interior decoration of early temples is found in the surviving cave temples. Although only a few wooden buildings have survived from the Tang period or earlier, hundreds of cave temples have survived. Here we offer glimpses of the three most famous cave temple complexes, Dunhuang in Gansu Province, Yungang in Shanxi Province, and Longmen in Henan Province.

Stupas are another feature of Buddhist temples. Often they are relatively undecorated but sometimes they contain art work. Hui-hsia Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “The stupa originated from the Indian funeral mound. In Buddhism the stupa is used to hold the reliquary remains of the Sakyamuni Buddha, and symbolizes Sakyamuni's attainment of ultimate extinction. Of the objects on display there is a T'ang stupa dating to 905 which is similar in style to the Stupa of Asoka. The four sides of the body illustrate the story of the past lives of the Buddha kyamuni, and giving (dana) on behalf of the enlightenment of all beings. The eave-type pagoda is a distinctively Chinese architecture form. On display is a Ming Dynasty stupa dating to 1631 which is in fine condition, with traces of painting remaining. Rising from the square body is a conical tower which slowly tapers to the top. The piece conveys a feeling of great height; the layers of brackets are thick and heavy without losing their subtle beauty. [Source: Chen, Hui-hsia, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Buddhist Sculpture in China

The most well known sculptures to come out of China are the images of Buddhas found in caves and sculptures unearthed from tombs. According to the Shanghai Museum:“The most attractive sculptures are Buddha statues with different styles, such as simple and delicate Buddha statues of the Northern Wei, elegant and vivid Buddha statues of the Northern Qi and the Sui dynasties, gorgeously shaped and full-bodied Buddha statues of the Tang dynasty, and novel and secular Bodhisattva of the Song dynasty.” Viewers can watch “a process how Buddhism, a foreign culture, was merging into Chinese traditional culture. [Source: Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum-net /+]

Early Tang sculpture

“Sculptures were popular during the Shang and Zhou dynasties and matured during the Qin and Han dynasties- The representatives of this period were terracotta army near the mausoleum of the First Emperor of the Qin and stone sculptures and wooden and earthen figurine from royal and elite tombs during the Han. Generally, pottery figurines of the Western Han showed simple technology and unadorned beauty. Those of the Eastern Han period exhibited more realistic in style and more vivid in facial expression and gesture. /+\

“Buddhism spread to China from India and Central Asia during the Han period. In the early Northern Wei period, Buddhist sculptures showed significant influence from Gandhara (northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan). Statues gave an appearance of westerners. Then, elegantly flowing robes and girdles appeared. Buddhist statues of the Western Wei exhibited strong bodies, round faces and full and intricately pleated robes. In the Northern Qi dynasty, statues became slim and graceful, with delicate garments and sharp linear details. Thoughtful facial expression was a typical style during the Northern Qi, which persisted into the Sui dynasty...Buddhist sculptures during the Song period emphasized the beautiful build of the human body. The development of sculptures during the Southern Song period was slow. Sculptures of the Yuan and Ming dynasties became formalized and routine, lacking creative works.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Among single Buddhist sculptures, one often finds sculptures of the Buddha, Buddhist monks, Bodhisattvas and guardian deities. The Buddha is at the core of the belief and represents the attainment of enlightenment. Disciples rendered in the form of monks transmitted his teachings after his death. Bodhisattvas were made in the image of a secular, royal prince—having reached Buddhahood, they chose to stay in this world in order to assist those who have not. Guardian deities look ferocious, but they avert physical enemies and internal demons. Then there are stupas, representing Nirvana. All these come together to compose the fundamental elements of Buddhist art. Besides the religious content of Buddhist sculptures, these objects also possess their independent artistic merit. Northern Wei sculptures tend to be modest and simple. T'ang sculptures are often rotund and lively. Starting from the Sung era, sculptures became more closely associated with ordinary people. In addition to revealing the technical development of each period, they also reflect their makers' standards of beauty. Thus, appreciating religious sculpture not only imparts their ideological ideals, but also conveys universal concepts of beauty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei ]

Some of the most exquisite Chinese sculpture was discovered at Qingzhou in Shandong in 1996 by workers leveling a sports field at a school. First the stone head of a Buddha was uncovered. Underneath that was a pit with 188 heads and 200 virtually intact torsos, and some monumental steles with Buddhist triads, and clay figures that were once brightly painted, some of them with “ash and burnt bones." The pieces were quickly excavated and stored in a museum without serious archeological work being done. They were of varying styles and time periods, and seemed like someone's private collection.

Types of Chinese Buddhist Sculptures

Hui-hsia Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “The Chinese used two major methods to cast bronze images: the piece-mold method and the lost-wax method. Using the piece-mold technique, a clay or sandstone model is covered with a layer of clay, which is cut and removed in two or more pieces to form an outer mold assembly. The outer mold is carved with decor and the outer surface of the model is scraped away; molten bronze is then poured between the model and outer molds. Decoration appears cast inversely on the object's surface. During the Six Dynasties period (317-587), the nimbus behind the head or body of many Buddhist images was cast separately using the piece-mold technique. [Source: Chen, Hui-hsia, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The lost-wax casting method involves the use of a wax model which is packed with clay. The wax model melts when the object is heated, escaping through a hole in the clay, to be replaced with molten bronze. Once the bronze has cooled, the clay layer is removed. Exceedingly complex designs can be produced through lost wax casting. By the Sui Dynasty (581-618) piece-mold casting was gradually replaced in favor of lost-wax casting, which has been used consistently thereafter. During the gilding process, a mixture of gold powder and mercury is applied to the surface of the bronze; the mercury evaporates when heated, and the gilding is polished, resulting in an indurate coat. Other details are also added, such as the vivid lines of the Buddha's eyes or the flowing folds in his monastic robe. \=/

“Collected works of stone and wood sculpture are typically large-scaled. Historical sources record the existence of abundant lifesize gilt-bronze Buddha images. Nevertheless, throughout periods of Buddhist persecution from the Northern Wei to the T'ang Dynasty, war, and economic decline, many pieces were destroyed or melted down so that the bronze might be reused for other purposes. Consequently, most surviving Buddhist bronzes are less than twenty to thirty centimeters in height. Large-scaled bronzes from the more recent Ming (1368-1644) and Ch'ing (1644-1911) Dynasties still found in Chinese temples are rarer than gilded wood and stone objects which were considerably more economical. \=/

“Given the difficulty of transporting large-scaled objects, few are to be found in local or international collections, therefore this exhibition of two sets of four large bronzes marks a particularly rare event. Small Buddhist bronze figures were easily carried on one's person as a talisman to provide self-protection during a journey or were placed upon a household altar to worship the Buddha. Unfortunately, many attachments have been lost, such as the throne, nimbus, and canopy, and the original assemblages of figures have long since been separated and dispersed among various collections. One can only imagine the magnificent and august atmosphere of the original Buddhist altars, furnished with splendid assemblies of Buddhist images, each over thirty centimeters high.” \=/

Early Buddhist Art in China

Early Buddhist art from the A.D. 5th century was influenced by the Hellenized Central Asian cultures of Kushen and Ganden and embellished with Chinese ornamentation. This art was mostly in form of Buddha statues and stelae, some of them dated and inscribed with their donor's name, carved out of rocks in caves such as those in Yungang near the Great Wall.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Emperors of the Northern Dynasties [A.D. 420-589] were Buddhists and used the religion as a system for unifying their rule. At the same time, they engaged in such religious activities as erecting temples and producing sculptures. Under the court's influence, the aristocracy and the rest of the people followed suit, believing that by performing these good deeds, they could gain more merit. Religious art became the essence of artistic creation at the time. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Buddhism of the Northern Dynasties mainly followed the Lotus Sutra, Vimalakirti-nirdesa Sutra and Mahaparinirvana Sutra. Sculptures often depict stout Shakyamuni Buddha, Maitreya or Avalokitesvara figures. From the strong figures of the early period, those of the middle period became more delicate. Along with the complex ones of the late period and serene ones of the Eastern Wei and Northern Ch'i, these sculptures reflect not only the artistic sensibilities of the particular periods, but also the religious views. ‘ \=/

“With an expanding empire and increasing royal patronage of Buddhism, contact with India was strengthened during the Sui and T'ang periods. T'ang monks went westward to India, and Indian monks made the reciprocal journey eastward, bring scriptures and injecting new life into Buddhism. With the emergence of educated monks and their ponderings on the nature of Chinese Buddhism, there emerged many different sects as Buddhism was gradually assimilated into Chinese culture. Buddhist art reached a new peak during the Sui and T'ang dynasties.

Early Buddhist Sculpture in China

According to the Shanghai Museum Beginning in the first century A.D., Buddhism came to China from India and Central Asia. The work of Buddhist missionaries relied not only on scriptures but also on images — Buddhism was sometimes called ‘the religion of images’. The earliest known Buddhist images with dated inscriptions are gilt bronze figures from the fourth century A.D. During the Northern Wei period (A.D. 386-535), Buddhist sculpture was under heavy influence from Gandhara (northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan). Figures of the Buddha from this period typically have deep-set eyes, strongly Western facial features, and stocky bodies. Toward the end of the Northern Wei period, however, these influences were assimilated and softened, and solid bodies gave way to elegantly flowing robes and girdles. When Northern Wei was succeeded by Eastern Wei (A.D. 534-550) and Western Wei (A.D. 535-557), styles in the western part of north China diverged slightly from those in the eastern part. In the eastern part, the Northern Wei style continued. Buddhist figures of Eastern Wei have close-fitting robes with the lines of pleats clearly and simply expressed. Those of Western Wei have robust bodies, faces that are round and full, and intricately pleated robes. Under the subsequent Northern Qi dynasty (A.D. 550-577) statues became slim and graceful, with delicate garments and sharp linear details. Northern Qi figures are notable for their wonderfully serene facial expressions, a characteristic which persisted into the Sui dynasty (A.D. 581-618). [Source: Shanghai Museum]

4th century gilded bronze seated Buddha

“Buddhist Stele Erected by Wang Longsheng and Others” (Northern Wei, A.D. 386-534) is so named because it is engraved with its pilgrims’ names: Wang Longsheng and others. It is carved in bas-relief. The upper part of the stele carving shows the debate between Manjusri Bodhisattva and Vimalakirti. The middle part of the niche is enshrined with a Buddha and two Bodhisattvas. Beneath it is a Buddha worshipping scene carved respectively with groups of figures either standing, walking, or riding on horse or carriage. The figures in the scene were presented strictly according to the ranking of honorable masters to humble servants, with the former in taller and larger images and the latter in gaunt and timid images. The carving of this stele is lively and vivid, embodied with complex contents, presented mainly through the skillful craft of bas-relief, with the carving on the back and the sides delicate and refined as well.

“Shakyamuni Buddha Stele Erected by Chen Huidang and Others” is dated to the 6th year of Datong, Western Wei, A.D. 540. The front of the stele is damaged. The middle and upper part is a niche, with a Buddha, a disciple and a Bodhisattva. Beneath both sides of the Buddha pedestal is a carved Dharma Lion with its mouth open and tongue out, strong and fierce. Two vajras in the middle are holding the pedestal with their hands, squatting sideways beneath it. There are two dragons on the niche lintel carved with refinement and delicacy. On both sides of the niche are carved three small niches lining from top to bottom containing a sitting Buddha. There are also three shrines on the left side of the stele arranged in the same way. Small as the niches and figures of Buddha are, just regarded as the foil and embellishment for the main niche and statue, the creators still applied their accomplished skills on every detail meticulously and optimized the style and appearance of each Buddha statue by different craft techniques such as fine carving and relief, making the whole layout a miniature of the statues in the cave of Grotto Temple. In the lower part of the stele is a long carved inscription, the calligraphy of which is neat and elegant.

In a stone statue of Sakayumi from the Northern Qi Dynasty (A.D. 550-577) the Buddhas sits crasslegged on a round double-waisted and lotus-petal-shaped stand. He has a peaceful, kindly, smile. Behind his back is a nimbus decorted with desogns of Buddha images, flames and floral pattern. This statue of Buddha has a plump face and gracious eyes with a kind expression and a faint smile. He wears a raglan robe with the drapes downward and stretching outward, like a pair of decorative wings in the wind. Standing barefoot on the pedestal, the Buddha with his broad body and elegant gesture started the transition in sculpture from the Northern Wei to the Eastern Wei.

Shakyamuni Buddha (Northern Qi, A.D. 550-577) is 164 centimeters tall. It is carved from a white marble. His face looks plump with his eyes half closed, looking downward, and the corners of his lips rise slightly in a faint smile. Both of his hands are incomplete, but the preaching gesture is still distinguishable. The gorgeous backlight of the Buddha foils the five Buddhas sitting on lotuses among flaming fire, with a lotus pattern in the centre, surrounded by a circle of lotus motifs. Shakyamuni Buddha looks graceful and elegant, with a clear, wise and kind expression, bearing a bright, intelligent and kind look, coupled with the fine and magnificent backlight, which creates a solemn harmonious feeling.

Group of Three Amitabha Buddhas (Sui Dynasty, A.D. 581-618 is 37.6 centimeters tall, 23.8 centimeters long at the base and 32.8 centimeters wide at the base and weighs 6.74 kg. The common bronze Buddha statue usually appears as a single piece, while this piece of work is presented in the form of an altar table, showing a sense of dimensional space, as if it is unfolding the Buddhist world in front of us. On this rectangular altar table stands an Amitabha with two bodhisattvas, two Buddhist pilgrims and two Dharma lions. There are two empty sockets on each side of Amitabha, originally designed to place statues of two disciples, which are lost. This triple statue of Amitabha shows exquisite workmanship. The haloes were lost-wax cast in openwork craft, the elaboration of which is stunning. Every grain of the pearls on the necklaces of Bodhisattva is clear and distinct. The lines (such as the hair) on the lions in the front were delicately incised after the whole piece was cast

Tang Buddhist Sculpture

The periods of Chinese Buddhist art closely parallel the phases the Buddhist religion went through in China. Works that appeared in the 5th and 6th centuries were very free and individualistic. In the Tang period the art became more mature and robust, with Buddhist figures featuring graceful lines and curves. In the 10th to 13th century Buddhist art became more refined. After that it was rooted in tradition and lacked innovation. According to the Shanghai Museum: “The Tang dynasty was one of the most brilliant epochs in Chinese ancient civilization. Sculptures of this period emphasized realism. Thus, various human figurines showed well- proportioned build and accurate appearance. Buddhist sculptures were given more perfect images in order to express the spirit of rescuing all living creatures.[Source: Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum-net /+\ ]

Hui-hsia Chen of the National Palace Museum, Taipei wrote: “ During the T'ang Dynasty, an indigenous religious tradition developed while Buddhism continued to flourish; hence, these pieces manifest characteristics of the T'ang style... Models brought back from India inspired new decorative motifs and aesthetic concepts. The volumetric and aesthetic concerns of Indian sculpture were skillfully incorporated into the unique flowing lines of Chinese sculpture. In the spirit of realism, sculptors revealed not only the Buddhist inner spirit, but also physical appearances through full bodies, flowing drapery lines, and soft movements. The dignified spirit of the Buddha was eloquently integrated into the midst of human nature and expressed through beautiful art forms.” A seated Buddha with representative voluptuous features dating to the High T'ang is small in size, yet conveys strength and vigor. [Source: Chen, Hui-hsia, National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

See Separate Article TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Printing in China

Buddhist monasteries were instrumental in the development of the world's first block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe that a person can earn merit by duplicating images of Buddha and sacred Buddhist texts. The more images and texts one makes the more merit one earns. Small wooden stamps — the most primitive form of printing — as well as rubbings from stones, seals, and stencils were used to make images over and over. In this way printing developed because it was "the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way" to earn merit.

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together on one 16-foot-long scroll. Because virtually all original Indian scriptures have been lost Chinese translations of Indian scriptures have been invaluable in trying to figure out what the original Indian texts said.

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “It is definitely known that actual books were printed in China during the ninth century, and probably such printing goes back considerably earlier. The world's oldest existing printed book is a Buddhist sacred text, dated in the year A.D. 868, and beautifully printed in Chinese characters. It was recovered some forty years ago from a cave in Northwest China, just at the point where the great Silk Road leaves China proper to plunge into the deserts of Central Asia. This book was not folded into pages like our modern books, but was a single roll of paper 16 feet long. Its dedication states that it was printed by a certain Wang Chieh "for free general distribution, in order in deep reverence to perpetuate the memory of his parents." [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

Over the years, printing displayed changes in Chinese Buddhist art. According to a National Palace Museum, Taipei description of a Yuan-era “The Buddha Preaching the Law”: “This woodblock print reflects the new "Tibetan-Chinese" style of the Yuan dynasty. The main figures (the Buddha and bodhisattvas) are Tibetan in style, but the others (disciples, donors, etc.) are all Chinese in manner. Two major changes are also seen in terms of composition. First, the main Buddha is not placed in the center, but rather off to one side preaching the Buddhist law. Second, before the frontal Tibetan style pedestal is a diagonal donor table. It indicates that the Chinese printing of the south (which originally reflected Tibetan influences) is gradually returning to Southern Sung Chinese traditions. The sketchy manner of carving suggests that this print dates from the late Yuan. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

Famous Chinese Sutras and Buddhist Scripture Masterpieces

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the Qing dynasty, many members of the imperial clan were devout followers of Buddhism. The courts in the Kangxi (1662-1722) and Qianlong (1736-1795) reigns witnessed the transcription and printing of the Kanjur Tripitaka in Tibetan and the Tripitaka in Manchu, while the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723-1735) selected and edited the contents of Record of Imperially Selected Lectures and A Drop in an Ocean of Sutras. In the imperial palace, many buildings included lecture halls for Buddhist scriptures and places for offerings to Buddhist images, while numerous displays and collections of Buddhist paintings and sutra books were found at other locations. These beautifully adorned and refined Buddhist texts and paintings were the private treasures of the imperial family.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm. gov. tw]

“The Buddhist texts on display here include imprints of the Sung (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties, works by famed calligraphers, and scriptures transcribed by monks. The Diamond Sutra, for example, is concise and pithy in wording yet also fully expresses the idea of prajña (wisdom) in popular Mahayana Buddhism, thereby spreadingSong and Yuan published imprints are often quite simple in nature, so many calligraphers took it upon themselves to transcribe them in brush and ink as a sign of sincerity and respect. In addition, illustrations of Buddhist figures form an expression of one of the three "bodies" of buddhas and bodhisattvas, that of appearance. The spectacle unfolding before the eyes, especially in colorful Esoteric School scriptures of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), is one of the most refined and dazzling to be found.

Another major text, The Hua-yen Sutra, expounds on the origins of the Buddhist world and the idea that all things are interconnected, being the scripture forming the basis and namesake of the Hua-yen School. Although originating in India, it later became one of the most important sects in Chinese Buddhism. The scriptures devoted to Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion, are intimately related to the development of Guanyin belief in the Chin and Sixteen Kingdoms era (280-439). Furthermore, after Dharmaraksa translated The True Dharma of the Lotus Sutra in 286 and Kumarajiva translated The Sublime Dharma of the Lotus Sutra, the image of Guanyin as a "savoir from difficulties and suffering" and "incarnation infinitum" became deeply planted in the minds of followers, thereby forming the basis of widespread views about Guanyin that are still held today.

Diamond sutra

Later Chinese Buddhist Art

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Since the 10th century, intellectuals became the main advocates of culture, gradually replacing the aristocracy. Buddhist stories also increasingly became the basis for folk tales and a part of history. Buddhism completely permeated people's daily lives in China. Sung religious sculptures became more secular and closer to ordinary people. With the rise in importance of painting, sculptures also became more painterly in effect. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Buddhist practices performed in religious devotion occurred frequently in the imperial clan during the Liao dynasty. The aristocracy and commoners alike sponsored the printing of scriptures, constructing of temples, and production of sculptures. Departing from the T'ang style inherited previously, a more independent style developed in Liao sculpture during the 11th century, where figures had strict, unsmiling visages and upright, stout torsos—expressing the unique power of the Khitan tribe. \=/

“The Ta-li rulers in Yünnan were devout Buddhists as well. In fact, 9 of the 22 kings became monks. Buddhist monks also took part in the civil service exams and became officials, reflecting the spread of the religion. Esoteric theology was the major sect. Influenced by Chinese beliefs, Taoism and local religions, it gained in complexity. Avalokitesvara was especially revered and many sculptures of this bodhisattva of compassion (known as Kuan-yin in Chinese) were carved. With myriad influences from neighboring Southeast Asia, a great regional style developed. \=/

“With the economic expansion of the Ming and Ch'ing, the spread of Buddhism no longer needed support from the court or the aristocracy. Believers focused their energy on producing copies of the scriptures, expanding further the reach of Buddhism. Though Buddhist theology did not experience major breakthroughs in this period, through religious occasions and activities, its basic beliefs permeated the lives of people and became an inseparable part of Chinese culture. Ming and Ch'ing sculptures, reflecting the pursuit of longevity, having sons, and gaining wealth and prosperity, leaned toward more earthly goals, often representing the familiar motherly figure of Avalokitesvara or the large-bellied Maitreya. Sculptural forms became more uniform and static, with an emphasis on outer appearances and often stripped of spiritual context. The court also had some Tibetan sculptures, characteristically detailed and elaborately decorated with colors pleasing to the eye, yet without dedication to the inner spirit of the Buddha.” \=/

Song, Yuan, and Ming Buddhist Sculpture

Sculpture of the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties (A.D. 960-1644) started out good but evolved towards banality. According to the Shanghai Museum: During the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1279) Buddhist sculpture acquired a new liveliness and elegance. Songs statues, mainly of painted clay and wood, depicted their subjects in a realistic way. Buddhist sculptures made in the Song period emphasize the beauty of the human form. Most seem to have been modeled on the figures of real people; carving is fresh and sharp. In the latter part of the Song period the pace of stylistic change seems to have slowed perhaps as a result of the Liao and Jin attacking from the north Buddhist figures made under Liao and Jin rule are sometimes identifiable by their robust figures and distinctive ethnic features. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Ananda was made during Song Dynasty (960-1279) from stone and is 172 centimeters tall. “Kasyapa and Ananda, often placed on each side of the Buddha, are the two most renowned among the ‘ten principal disciples’ of Shakyamuni Buddha. Kasyapa is looking to the left, with a calm and steady expression, standing barefoot on the lotus seat with his hands folded in front, like an ascetic monk full of the rigors of life. Ananda is standing bareheaded, with beads in one hand and the other overlapping on the wrist, like a witty child. With Ananda looking to the right side, facing Kasyapa, the two disciples seem to be engaged in a friendly conversation. Their expressions are natural and lively, which is a manifestation of the joy of life. As a classic work of Northern Song statuary, this pair of almost life-sized statues of Ananda and Kashyapa is of extreme rarity.

Under the Yuan (A.D. 1279-1368) and Ming (A.D. 1368-1644) dynasties much sculpture was formalized and routine; in Buddhist sculpture and tomb figurines alike, really creative works are few. A dry formalism characterizes much Buddhist art of the Ming and Qing (A.D. 1644-1911) periods, perhaps owing to the decline of the religion itself, but some fine works were nevertheless produced. The Ming and Qing periods are known mainly as a time when traditional Chinese crafts and decorative arts reached a high level, producing some wonderfully intricate and beautiful pieces.

Chinese Buddhist Paintings

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Buddhist painting and calligraphy includes examples of calligraphed sutras by famous calligraphers and paintings of such Buddhist figures as devarajas (heavenly kings), the bodhisattvas Manjusri and Guanyin, and lohans. In addition to featuring the unique and skilled expressions of painters and calligraphers, Chinese Buddhist art also includes Buddhist figures centered on the Amitabha Buddha along with the bodhisattvas Samantabhadra and Manjusri, Guanyin, heavenly kings and Chinese and Tibetan renderings of lohans. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Great Master, Guanyin” by Chao I (fl. late 14th century), Yuan Dynasty is a hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, measuring 108 x 54.8 centimeters. On a cliff with shoots of bamboo sits the white-robed Guanyin bodhisattva with a dragon-lady attendant behind. In Guanyin's hand is the bottle of purification, emanating from which is a wisp of a cloud. On it stands Sudhana, the Child of Virtuous Wealth, bending forward in respect.

“Lohan Pu-tai” by Chang Hung (1577-after 1668), Ming Dynasty is a hanging scroll, ink on paper, measuring 60 x 30.6 centimeters. The monk Cloth Sack (Pu-tai), of the Five Dynasties period, was said to be short and fat, having a deep brow and round belly. He carried his belongings in a cloth sack tied to a cane, hence his name. When begging, he would mutter "Maitreya, True Maitreya". After passing away, he was reincarnated with his cloth sack. He was felt to be an incarnation of Maitreya, thus the many images of him in Zhejiang and Jiangsu.

In chapters 65 and 66 of Journey to the West, the attendant Yellow Brow, said to be a disciple of the Maitreya Buddha, stole the Master's cloth sack of treasures and descended to the mortal realm to wreak havoc. Flinging the sack in battle, the opponent would be engulfed at once. The Monkey King begged Maitreya, who used his powers to capture the mischievous attendant. In the novel, Maitreya is described as follows: "With a wide visage of large ears and broad cheeks, the whole of his body from shoulders to belly is corpulent. He, like the New Year, is overflowing with merry, eyes beautifully bright and vast. He, covered in flowing sleeves of gracious good fortune, has a robust spirit spreading far and wide. He, the foremost Buddha in the land of Paradise, is the laughing Buddhist monk Maitreya.", This is exactly the laughing appearance of Maitreya that we see in this painting.

“Cundi” by an anonymous Ming dynasty(1368-1644) artist in a gold and colors on paper hanging scroll measuring 126.7 x 81.1 centimeters. The background of this painting is rendered in dark blue. Depicted here is a large lotus blossom above the waves upon which Cundi, a form of Guanyin, solemnly sits cross-legged. The figure wears a five-pointed crown and jewelry draped across the torso. The face is distinguished by a third eye, and the figure features 18 arms. Some of the hands form mudras (gestures), while most hold ritual objects. In each corner above, a heavenly deity approaches on clouds, while two dragon kings below support the lotus stem. The monk in the lower right probably is a Cundi practitioner. The work was done in gold ink with fine flowing lines, and the drapery patterns complete and detailed, making this a fine Buddhist painting of the Ming dynasty.

“Great Master, Samantabhadra by an anonymous, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) painter is a hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, measuring 156.6 x 94 centimeters. Samantabhadra is an attendant bodhisattva of Shakyamuni Buddha, the other being Manjusri. Important bodhisattvas in the Buddhist pantheon, Manjusri rides a lion on the left, representing wisdom. Samantabhadra rides a white elephant on the right and is in charge of reason. Appearing on either side, they represent the accommodation of both wisdom and reason in the Buddhist faith. This image is in the form of a monk, which, according to custom, makes it more accessible to lay Buddhists.

Song Dynasty Buddhist Paintings

Song-era stone Guanyin

Most existing examples of Chinese Buddhist painting that date to the Tang Dynasty or before are found in cave temples in northern and western China (See Separate Article on Buddhist cave art). The oldest and most exquisite examples of Buddhist painting on paper and silk date mostly to the Song Dynasty.

“Lohan”, a Buddhist painting attributed to Li Sung 1190-1230, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 104-x-19.5 centimeters). “Lohan is the Chinese term for arhat, which is used to describe a disciple of Buddhism who achieved a certain level of cultivation and escaped from the cycle of birth and rebirth. The lohan shown here is leaning on a bamboo cane with both hands and is sitting on a meditation seat. He has two attendants — one holds an incense holder and the other prepares a basket of flowers. His hair has turned white and he stares forward with a solemn expression. The drapery lines flow with grace yet strength. The use of brushwork in this painting is exceptionally refined, as seen in the clusters of drooping willow leaves above and the decoration of the seat and stand next to the lohan, making this is one of the masterpieces of Buddhist and Taoist figure paintings in the Museum collection. Although this painting bears no signature or seal of the artist, it has been attributed in the title slip to Li Sung, who served as a Painter-in-Attendance at the Southern Sung court between 1190 and 1230 and specialized in Buddhist and Taoist figures as well as the ruled-line style of painting. However, judging from style, this work probably came from the hand of a Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) artist. \=/ [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Guanyin of a Thousand Arms and Eyes,” by an anonymous painter, is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 176.8 x 76.2 centimeters. “Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion stands on a lotus pedestal supported by four Guardian Kings. Above are seated Buddhas on auspicious clouds and below are eight Deva Kings in two rows. Guan-yin here has a moustache, but also an elegant face and delicate figure, clearly revealing feminine characteristics. Guanyin with many heads and arms comes from esoteric Buddhism, which entered T'ang China under Kao-tsu (r. 618-626). The top of Guanyin's head has 26 heads of bodhisattvas and one of a Buddha. Guanyin has 1,000 hands, each of which has an eye in the palm. A visualization of Guanyin's ability to see and assist all, this work reflects the deity's compassionate nature. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Against the background of a myriad billowing waves and auspicious clouds spewing forth, stands a majestic Guanshiyin (or Guanyin) Bodhisattva of a Thousand Hands and Eyes supported by the Four Heavenly Kings holding up a bejeweled lotus pedestal. On Two attendant bodhisattvas clasp their hands in reverence on either side of Guanyin, and next to them are two others in attendance holding Buddhist implements. The Guanyin here appears with facial hair, indicating a manifestation in male form, but the eyes and eyebrows are delicate and elegant. Combined with the warm and gentle look, the figure already reveals the manner of a female deity. Although this scroll bears neither seal nor signature of the artist, the outlining of the figures and lines of the drapery patterns were all done using strokes from a centered brush. The brushwork is fluid and spirited, the necklace decoration and gems inlaid onto the bejeweled lotus pedestal painted with exceptional detail. The coloring is beautiful but not vulgar, making this a masterpiece of Southern Song Buddhist painting. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “During the late Song, among the non-professionals who took to painting as a form of self-expression (or, perhaps, no-self-expression) were Zen monks and lay practitioners. They worked towards a highly reduced form of brush painting — just as Zen, the Buddhist school which prized nothing but meditation itself, was the most stripped-down form of Buddhism. A painting by a Song painter who went by the pseudonym of Muqi, is celebrated as the ultimate in painterly simplicity. Six persimmons are represented by ink lines and washes so elementary that it would seem like a school kid could have done them (the same type of comment later made of Picasso in the West) — yet the rendering and placement of the persimmons was an unprecedented artistic innovation. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University]

Yuan Buddhist Art

Guanyin acolytes

By the Yuan period (1271–1368) Tibetan Buddhist influences were common in Chinese court art and Yuan period artists produced their share of Buddhist and Tibetan Buddhist art. “The Buddha Preaching the Law” is woodblock print that reflects the new "Tibetan-Chinese" style of the Yuan dynasty. The main figures (the Buddha and bodhisattvas) are Tibetan in style, but the others (disciples, donors, etc.) are all Chinese in manner. Two major changes are also seen in terms of composition. First, the main Buddha is not placed in the center, but rather off to one side preaching the Buddhist law. Second, before the frontal Tibetan style pedestal is a diagonal donor table. It indicates that the Chinese printing of the south (which originally reflected Tibetan influences) is gradually returning to Southern Sung Chinese traditions. The sketchy manner of carving suggests that this print dates from the late Yuan.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

"Hevajra" was originally ascribed as a Yuan Mahakala tapestry. “Hevajra is one of the five main deities in Tibetan Buddhism. A believer could choose any Buddha, bodhisattva, or protector as a "principal deity" of worship and practice throughout life. The popularity of Hevajra was mainly due to the faith of Kublai Khan. It was in 1253 that Kublai Khan and his consort Chabi were converted to Buddhism by Tibetan high monk Phagspa. They received the tantric baptism of Hevajra as practiced in the Sakya sect of Phagspa. In the personification of Buddhist ideals and practices, Hevajra stood for wisdom and compassion as well as the overriding power of Buddhism. Thus, Hevajra is shown here trampling on four figures to symbolize overcoming one's difficulties. \=/ [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

A thanka of Onpo Lama Rimpoche, (Fourth Abbot of the Taklung Monastery) was made in the 13th century. The Taklung Monastery, the main monastery of the Taklung Sect, is situated 65 kilometers north of Llasa. In 1240, the Mongol general Godan sent To-ta to Tibet in preparation for an assault. To-ta returned and informed him that "Monks of the Taklung monastery are of the highest morals." Indeed, the two Taklung thankas in this exhibit have inscriptions on the reverse that emphasize the importance of the virtues of "restraint" and "perseverance" for monks. For this reason, Taklung clergy were respected by the Yuan imperial precept Phagspa and received the patronage of Kublai Khan. Buddhists revere the "Three Treasures" of the Buddha, the Law, and the clergy. Most of the surviving portraits from the Yuan dynasty are from the Taklung Monastery, which established a norm and a didactic model for posterity. \=/

Indian influences were also found in Yuan-era court art. National Palace Museum“Amitabha Buddha, Sung to Yuan Dynasty, is an example of this. “In the 13th century, as Genghis Khan was commanding his armies to the north, the Buddhist holy land of India came under the control of Muslim leaders. The last classic phase of Indian Buddhist art from the Palas dynasty (750-1200) reveals the classic elegance and introversion of Gupta (5th century) art with the decorative and delicate esoteric features of East Indian art. Fortunately, the Palas tradition was preserved in Nepal and Tibet. But what exactly is the East Indian Palas style? The figure in this work is elegant and the coloring clear. This work is representative of a thanka from the Kadam sect of central Tibet.” \=/

Buddhist Art in Illustrated Chinese Texts

The National Palace Museum has a rich collection of Buddhist texts, which are accompanied by many beautiful prints of monks, guardians and deities. There are also images illustrating miracles of Buddha rescuing people from hardships. These works are presented in a righteous, dignified, and compassionate manner. Their features are lifelike, and the scenes deeply inspiring and moving. Many are influenced by Tibetan Buddhism

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““Members of the Buddhist world include buddhas and bodhisattvas, guardian deities, monks, and believers. Some of them are historical figures; others are non-human deities and spirits. Because of their different personas, they are given unique appearances and features. In the process of preaching Buddhism, these characters often experience extraordinary miracles. Part of these events are documented in the sutras, such as Pumenpin (addharmapundarika-sutra), which records Avalokitesvara helping people in hardships, and Yaoshijing ("The Sutra of Bhaisajyaguru"), which describes the Medicine Master's twelve vows. Some of the stories were brought into China and transformed into popular novels and operas. Examples include Xiyoujivel (Travel to the West), a Chinese classic detailing the Buddhist monk Xuanzang's pilgrimage to India, and Xinxiao Xiwen (Play: Mulian's Filial Duty to His Mother), a song performance about Mahamaudgalyayana's passage to the underworld to rescue his mother. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Xuanzang in “Xiyou Zhenquan” (“A Complete Narrative of Travels in the West”), text written by Wu Chengen (ca. 1500-82) and nnnotated by Chen Shibin (n.d.), is a Qing imprint of the Qianlong reign (1735-1796) by the Shidetang Printhouse, measuring 29.2x25.7 centimeters. “Xuanzang (600-664CE), whose mundane name was Chen Yi, was born in Luoyang, Henan. His family was poor, and he studied Buddhism in Louyang with his elder brothers in Jingtu Temple. He had already understood all the teachings in China when he was about 20. However, he thought that he didn't understand the ultimate truth of Buddhism, he then decided to go to India for further study. He started his journey throughout five regions of ancient India from 629 to 645 CE. He learned many commentaries of sutras from Master Jiexian and was famous in Tienzhu for successful convinced many local monks in Kannauj. Latter he was given the title of Mahayanadeva. After he went back to China, he started translating Buddhist scriptures in Hongfu Temple of Changan and Yuhua Temple. He was the greatest translator in Chinese Buddhism and he had translated 75 sets and 1135 volumes of Buddhist scriptures before he died, including the famous "Yogacara-bhumi", "Kowa-wastra," and "Maha-prajñaparamita-sutra". In addition, he was also a famous traveler and his important historical and geographical oral work of “Datang xiyuji (The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions)" recorded his knowledge about the customs of places where he had traveled. And the story of this pilgrimage became the theme of novels, such as the Wu Chengen's Xiyouji (Journey to the West) is one of famous works in Ming dynasty, which describes that Xuanzang's pilgrimage with his three disciples (Sunwukong, Zhubajie and Shawujing) and they encountered the 81 obstacles during their journey.

“Bhaisajyaguru Vows” in “Yaoshi liuiguang rulai benyuan kongdejing” (“Bhaisajyaguru-vaiduryaprabhasa- tathagata-purvapranidhana-guna-sutra”), translated by Xuanzang of the Tang dynasty (618-907) is a handwritten edition of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), measuring 26.6 x 9.3 centimeters. Bhaisajyaguru is believed to be the founder of the Pure Land in the east and he was also called "the Emperor of Medicine" because he felt the grief from all the living being and swore to them. His two sons also accompanied him as the Sunya-prabha and Candra-prabha. This book recorded his twelve vows, each with a painting. The painting can be divided into two parts: the upper part depicted a halo in the cloud, with the Bhaisajyaguru sitting in a vihara, with different hand signs; the lower part recorded the contents of each vow. The twelve vows are: 1. to illuminate countless realms with his radiance, enabling others to become a Buddha too; 2. to awaken the minds of sentient beings through his light of lapis lazuli; 3. to provide the sentient beings with whatever material needs they require; 4. to correct heretical views and inspire beings toward the path of the Bodhisattva; 5. to help beings follow the Moral Precepts, even if they failed before; 6. to heal beings born with deformities, illness or other physical sufferings; 7. to help relieve the destitute and the sick. 8. to help women who wish to be reborn as men achieve their desired rebirth; 9. to help heal mental afflictions and delusions; 10. to help the oppressed be free from suffering; 11. to relieve those who suffer from terrible hunger and thirst; 12. to help clothe those who are destitute and suffering from cold and mosquitoes.

Image Sources: Tang sculpture, University of Washington; Metropolitan Museum of Art; Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei ; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated November 2021