CHINESE BUDDHISM TODAY

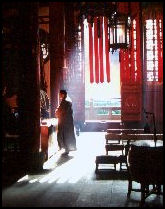

Worshipping in a Buddhist temple in Shanghai

Beijing generally feels less threatened by Buddhism than it does by Christianity because of its homegrown roots, but it does maintain control over monasteries, especially in Tibet. Buddhism strong association with Tibet doesn't make it very popular with the Communist regime.

In August 2004, a U.S.-based Buddhist leader was detained and dozens of his American followers were forced to leave the country. The leader and his group has spent $3 million renovated a 800-year-old temple in Inner Mongolia. The leader, who is regarded as a “living Buddha," was charged with “promoting superstition” and taking control of the temple.

In March 2006, China hosted its first major international forum on Buddhism since 1949. About 1,000 monks and scholars from 10 countries, including Hong Kong and Taiwan attended. The theme of the forum was “a harmonious world begins in the mind." The 16-year-old Panchen Lama showed up at the event and gave a scripted, pro-Beijing speech. Human rights groups called the meeting “cynical propaganda aimed at drawing attention away from China's repressive policies in Tibet."

Websites and Resources on Buddhism in China Buddhist Studies buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in China Wikipedia Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Buddhist Art: Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn ; Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Buddhist Artwork buddhanet.net/budart/index ;Buddhism and Buddhist Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Buddhist Art Huntington Archives Buddhist Art dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart ; Buddhist Art, Smithsonian freersackler.si.edu; Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; Mahayana Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ; The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ; Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ; Chinese Religion and Philosophy: Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LOTUS SUTRA AND THE DEFENSE OF BUDDHISM AGAINST CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com; CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES, MONKS AND FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM VERSUS THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey” by Kenneth Ch'en Amazon.com; “Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China” by Christine Mollier Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com Schools of Buddhism in China: “Chan Buddhism” by Peter D. Hershock Amazon.com; “The Essence of Chan: A Guide to Life and Practice according to the Teachings of Bodhidharma” by Guo Gu (Author) Amazon.com; “Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice” by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com; Famous Sutras: “The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic” by Gene Reeves Amazon.com; “The Lotus Sutra” by Burton Watson Amazon.com; “The Diamond Sutra” by Red Pine Amazon.com

Buddhist Revival in China

Buddhism is experiencing something of a comeback. It is becoming increasingly popular with China's wealthy and is increasingly embracing modern methods to reach them. In southern China a Buddhist temple spent $24,000 for advertising time on the Good Morning, Fujian television show. Guangdong Province's Guangxiao Temple, said to be the larget and oldest Buddhist temple in southern China, has launched on online worshiping system (www.gzgxs.org/Geneflect/indesx.asp ) which offers users virtual incense, fruit, flowers and a variety of electric Buddhas.

Buddhism is experiencing something of a comeback. It is becoming increasingly popular with China's wealthy and is increasingly embracing modern methods to reach them. In southern China a Buddhist temple spent $24,000 for advertising time on the Good Morning, Fujian television show. Guangdong Province's Guangxiao Temple, said to be the larget and oldest Buddhist temple in southern China, has launched on online worshiping system (www.gzgxs.org/Geneflect/indesx.asp ) which offers users virtual incense, fruit, flowers and a variety of electric Buddhas.

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian: “ During the Cultural Revolution, temples were closed down and some suffered serious damage. In my little town, Red Guards knocked off the heads and arms of every Buddhist sculpture in the local temples, which were then converted into storehouses. Afterwards, the damaged temples were restored and they all reopened, typically with two round bronze incense burners in front of the main hall: the first to invoke blessings for wealth, the second to invoke blessings for security. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018. Yu Hua is a famous writer in China, considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize. He is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant”, “To Live” and “Brothers.”]

“When I visited temples in the 1980s, in the first censer I would often see a huge assembly of joss sticks, blazing away furiously, while in the second, a paltry handful would be smoking feebly. In those days China was still very poor, and, as most people saw it, when you didn’t have money, being safe didn’t amount to much. Now China is rich, and when you go into a temple you see joss sticks burning just as brightly in the security censer as in the wealth one — it is when you are rich that security acquires particular importance.

“In China today, Buddhist temples are crowded with worshippers, while Taoist temples are largely deserted. A few years ago, I asked a Taoist abbot: “Taoism is native to China, so why is it not as popular as Buddhism, which came here from abroad?” His answer was short: “Buddhism has money and Taoism doesn’t.” His explanation, although it rather took me aback, expresses a truth about Chinese society: money, or material interest, has become the main motivating force.

Wutaisan (300 kilometers southwest if Beijing) , the most important of China's four holy mountains, has become a Mecca for Chinese seriously interested in Buddhism as well as tourists. One itinerant monk there told AFP, “I have come to Wutainshan because Zen Buddhism, Han Buddhism , Tibetan Buddhism, all the schools from different places are represented here." A spokesman for the Wutaishan Buddhist Association told AFP, “Twenty years ago, as we started recovering for the Cultural Revolution, there were just a few hundred monks. Since then Buddhism hasn't stopped developing. More and more monks have come. The number hit 1,000, then 2,000, then 3,000. [In 2006] we hit 5,000." At that time the government stepped in a restrict the number of monks. In 2008, 2.8 million visitors came to Wutaishan and spent $206 million according to government numbers. Other temples that have recorded record numbers of visitors include Hongfa Temple in Guangdong Province, an important Buddhist site, and White Horse Temple in Henan Province, China's oldest Buddhist place of worship.

Yuppie-Fueled Revival of Buddhism in China

Taiwan Buddhist worship meeting

Buddhism is finding a receptive audience among China's urban middle class. Perry Garfinkel wrote in National Geographic: “On the surface, Chen Xiaoxu is a most unlikely poster child for this renaissance. At 39 she heads one of Beijing's top advertising agencies, but she's better known as a former Chinese television star. She started her agency in the early 1990s, when advertising in China was in its infancy, soon earning success beyond her dreams. "Once I got the taste, I always wanted more and more, bigger and bigger status symbols," she tells me, as we sit in the conference room of her company, Beijing Shipang Lianhe Advertising, in a modern Beijing high-rise. Her long neck and delicate features evoke Audrey Hepburn, whose portrait hangs on the wall behind her, but her warm, empathetic eyes mirror paintings and sculptures I've seen of Guanyin, Chinese Buddhism's female representation of compassion. [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005 ^*^]

“Gradually, she says, it took hold — that feeling of emptiness so many people experience when they have all the material possessions they desire. In Buddhism this desire has a nickname: the Hungry Ghost, an appetite that can't be filled. "Though I had it all — big car, beautiful house, travel wherever I wanted, surrounded by fame and luxury with plenty to share with my family — I was still, somehow, unhappy." ^*^

“Then someone gave Chen a book about the life and teachings of the Buddha, and she became a serious student of Buddhism. Now one wall of her stark white office is dedicated to pictures of her teacher, Chin Kung, as well as Buddhist statues and paintings. Her employees know to hold phone calls during lunch hour, when she takes a break to meditate and chant. A Buddhist in a profession whose goal is to whet the appetites of the Hungry Ghost” What's no less remarkable is that so public a figure as Chen Xiaoxu is openly practicing Buddhism in communist China.” ^*^

China’s New Generation of Techy-Buddhists

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: “For centuries, Buddhists seeking enlightenment made the journey to Longquan Monastery, a lonesome temple on a hilltop in the hinterlands of northwest Beijing. Under the ginkgo and cypress trees, they meditated, chanted and pored over ancient texts. Now a new generation has arrived. They wear hoodies, watch television shows like “The Big Bang Theory” and use chat apps to trade mantras. Many, with jobs at some of China’s hottest and most demanding companies, feel burned-out and spiritually adrift, and are looking for change. “Life in the outside world is chaotic and stressful,” said Sun Shaoxuan, 39, the chief technology officer at an education start-up. “Here, I can be at peace.” [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, September 7, 2016]

Religious service in Shanghai

“Today, young entrepreneurs make the pilgrimage to Longquan in hopes of creative epiphanies. They work at some of China’s most prominent technology companies, including JD.com, an e-commerce giant, and Xiaomi, a smartphone maker. “Some of the people who come here may not actually be incredibly interested or believe in Buddhism,” said Rax Xie, a software developer. “But they will have a certain connection and receptiveness to the thought and culture behind Buddhism.”

“On Sunday mornings, Mr. Sun, the technology entrepreneur, makes his way from his suburban apartment to Longquan. He slips on a maroon robe and begins to chant. Mr. Sun was once a skeptic of religion. But after a spiritual awakening last year, he said he came to embrace Buddhism, eschewing meat and alcohol and persuading his wife to join him on his spiritual journey. I met Mr. Sun at a chanting ceremony one Sunday at Longquan. The meditation hall was covered in pillows decorated with lotus flowers; a large, gleaming Buddha statue rose from the front. A wiry man with soft, dark eyes, he sat in the first row of worshipers, a bell in his hand, and wore a golden sash reading, “Thanks to those who taught me salvation.”

“After the ceremony, he told me about his transformation. As he saw it, he was once self-centered and angry, prone to barking orders at his family and co-workers. While his mother was a Buddhist, he saw the religion as “just a story.” Then, in the fall, he attended a three-day retreat at Longquan intended for information technology workers. He was forced to give up his cellphone and passed the time by meditating, listening to lectures and working in the garden. Almost immediately, he said, his mind felt cleaner and lighter. Mr. Sun and his wife now attend services nearly every week. In the afternoons, he performs maintenance on Longquan’s websites and helps organize workshops on back-end programming. He said he had come to see the temple as a “small utopia, free of conflict,” in a society that could sometimes feel riddled with deception. “When you go to the mountain, you don’t need to think: ‘Who will trick me? Who will harass me? Who will think badly of me?’” he said. “Once you have a sense of security and trust, then you will want to open up, help others and explore your beliefs.”

Longquan Temple: Ground Zero for China’s High-Tech Brand of Buddhism

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: As a spiritual revival sweeps China, Longquan has become a haven for a distinct brand of Buddhism, one that preaches connectivity instead of seclusion and that emphasizes practical advice over deep philosophy The temple is run by what may be some of the most highly educated monks in the world: nuclear physicists, math prodigies and computer programmers who gave up lives steeped in precision to explore the ambiguities of the spiritual realm. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, September 7, 2016]

“To build a large following, the monks have put their digital prowess to work. They have pioneered a popular series of cartoons based on Buddhist ideas like suffering and reincarnation. (“Having a bad mood can ruin one’s good luck,” a recent cartoon said.) This past spring, they introduced a two-foot-tall robot named Xian’er to field questions from visitors, the temple’s first foray into artificial intelligence.

“Traditionalists worry that Longquan’s flashy high-tech tools may have muddled the teachings of the Buddha, the dharma. They say its emphasis on practical topics like resolving family conflict and achieving success neglects more important philosophical questions. But the leader of the monastery, the Venerable Xuecheng, who dispenses bits of wisdom every day to millions of online followers, has defended his approach, saying that Buddhism can stay relevant only by embracing modern tools. In a computer-dominated world, he has said, it is no longer realistic to expect people to attend daily lectures. “Buddhism is old and traditional, but it’s also modern,” he said in an interview in March with the state-run news agency Xinhua. “We should use modern methods to spread the wisdom of Buddhism.”

part of Longquan Temple

“On a recent Sunday morning, I stood outside Longquan’s gates, watching as hundreds of volunteers and tourists ascended to the temple. They bowed to one another and took turns sweeping cracked walkways. Some wandered through the organic vegetable garden, stopping to prop up unruly tomato plants. The modernity of the temple was inescapable. While it was first built in 957, many of its original structures were demolished by war and, more recently, by the Cultural Revolution, when Chinese Buddhists were persecuted. Only at the turn of the century was the temple salvaged and rebuilt by a Buddhist businesswoman, Cai Qun. It reopened in 2005, and it is now equipped with fingerprint scanners, webcams and iPads for studying sutras, or Buddhist texts.

“Longquan’s proximity to several of Beijing’s top universities and the city’s main science and technology hubs has made it popular among young people. Many of them are searching for deeper meaning in a society rife with materialism. Others seek an escape from grueling schedules, and tips on relaxation. The temple is renowned in start-up circles, in part because of a widely circulated rumor involving Zhang Xiaolong, one of the inventors of WeChat, a popular messaging app. News articles have claimed that Mr. Zhang, having hit a stumbling block, attended a retreat at the temple, after which he gained inspiration for WeChat. (Mr. Zhang, through a spokesman, denied the reports.)”

Longquan Temple: a Showcase for Beijing-Sanctioned Soft Buddhism?

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: “The state-run news media speaks of the temple in almost mythical terms. In success-driven China, many people marvel at the decision of the temple’s monks to leave behind lucrative careers in the tech sector to devote themselves to Buddhist study, rising at 3:55 a.m. each day for morning prayers. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, September 7, 2016]

“Longquan has become a favorite showpiece for the ruling Communist Party, which officially promotes atheism but has led a push in recent years to revive ancient cultural traditions. In addition to leading Longquan, the Venerable Xuecheng is the president of the Buddhist Association of China, a party-controlled supervisory organ. The temple displays the writings of President Xi Jinping, and long-term residents must submit information about their patriotism and political views. In a kind of soft-power spiritual push, the Venerable Xuecheng has sought to turn the teachings of the monastery into a global export, translating his writings into more than a dozen languages. In July, he helped open a temple in Botswana for Chinese expatriates.

Business-Minded Chinese Buddhist Monks

Several monks at Jade Buddha Temple have gotten MBAs, with special classes in temple management, at the Antai School of Management. The temple's manager Chang Chun told the Times of London, “We live in the metropolis of Shanghai and need to find a way to interact between Buddhism and society. This requires a different management style." A monk taking the course said, “We have a strong sense of faith but our commercial knowledge is weak. Now we have many more opportunities to meet people from the secular world and need to understand how o deal with and negotiate with outsiders."

Behind Jade Buddha Temple is a glass-and-marble building where its business-minded monks work and figure out ways to make money and better manage their temple. Jane MacCartney of the Times of London wrote, “In temple offices, shaven-headed monks dressed in saffron robes sit in cubicles like those fond in London banks. Some peer at computer screens and answer telephone calls; others monitor visitors by walkie-talkie."

Entrance to the temple is $1.35. Bunches of incense sticks are sold for about $5 at the temple shops. Around the temple are boxes for donations. For $1,360 one can buy a gilt Buddha statues with a plaque bearing the owner's names at the temple entrance. For a fee one can also get their car, home, or jewelry blessed or have prayers said for good health and wealth.

Shaolin Business Deals

Longquan Temple

In the late 2000s, Guandu, a town that has been absorbed by Kunming city, spent $3 million to rebuild the four temples to draw tourists but no one came. To draw visitors, Guandu officials struck a deal with business-savvy warrior monks of Shaolin. In exchange for managing the Guandu temples for 30 years, the monks will keep all proceeds from the donation boxes and gift shops. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 1, 2009]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Guandu officials say they will get no money from the deal, but they hope the Shaolin mystique will pull in the kind of crowds that have turned Shaoilin monastery into one of China's most popular tourist destinations. On Guanda official said the government would save the $88,000 once spent on temple maintenance each year. They are also counting on the tax revenue from a vast new mall that is nearing completion next to the temple complex."

“The management deal has provoked howls among some Chinese, with many critics decrying the commercialization wrought by the Yongxin. Shaolin Chain Store, read the headline of one recent posting written on Sina.com, a popular Web site. There's nothing wrong with chasing profits and fame, but they can't use the name of Buddha."

‘such sentiments are hard to find in Guandu, where people seem to enjoy the sudden uptick in tourism...A squadron of incense vendors surged around visitors, and the Liu family noodle shop was doing a brisk business feeding the famished. Before the monks came, the only people who came were old, and they didn't spend any money, said Cao Jinbu, the shop's owner. Wan Liqiong, who runs a trinket stand across from the temple gate, said she would probably have to switch some of her stock to include Shaolin-oriented souvenirs."

“After reading about the Shaolin deal in his local newspaper, Ying Daojin made the eight-hour journey by bus just to catch a glimpse of the monks. A 30-year-old corn farmer from northeast Yunnan, Ying described himself as a nonbeliever but seemed willing to give religion a try. I've heard Buddhism can open your mind, he said wide-eyed as a monk glided by. Kung fu is also good for your health."

“The Shaolin monks were decidedly unapproachable. The young men waved away inquiries. When one bespectacled monk found himself the subject of a photographer's interest, he grabbed the camera and then offered a menacing martial arts pose when his demand to have the picture erased went unmet. Negotiations proved fruitless, and the pictures were deleted. The monk bowed, smiled and walked away. Others were busy helping to renovate the gift shop while another group of monks was handling the bequest of an adherent who had stopped by bearing gifts.

A few days after their arrival, the monks taped a handwritten poster at the temple entrance advertising kung fu lessons. The cost: $44 for a month of instruction, nearly a full month's wage for some Chinese workers. The security guard at the front gate said the classes were selling well, with more than 100 people already signed up. He showed off the student roster, most of them children and teenagers. Everyone loves the Shaolin monks, he said with a smile." Yongxin, who drives a Land Rover and has established Shaolin branches in Italy, Germany and Australia.

See Separate Article: KUNG FU IN CHINA, SHAOLIN TEMPLE AND BRUCE-LEE-STYLE KUNG FU factsanddetails.com ; SHAOILIN TEMPLE, ITS FIGHTING MONKS, KUNG FU AND SACRED MOUNT SONG factsanddetails.com

Fo Guang Shan

Shaolin monks

Fo Guang Shan (“Buddha’s Light Mountain”) is popular in China these days. Founded in 1967 by Hsing Yun, it is a Chinese Mahayana Buddhist organization based in Taiwan that practices Humanistic Buddhism and is known for its efforts in the modernization of Chinese Buddhism. The order is famous for its use of technology and its temples are often furnished with the latest equipment. Hsing Yun' has said: Fo Guang Shan is is an "amalgam of all Eight Schools of Chinese Buddhism" [Source: Wikipedia]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times:“Fo Guang Shan is perhaps the most successful of the new Buddhist groups in China. “Since coming to China more than a decade ago, it has set up cultural centers and libraries in major Chinese cities and printed and distributed millions of volumes of its books through state-controlled publishers. While the government has tightened controls on most other foreign religious organizations, Fo Guang Shan has flourished, spreading a powerful message that individual acts of charity can reshape China. [Source: Ian Johnson New York Times, June 24, 2017]

“It has done so, however, by making compromises. The Chinese government is wary of spiritual activity it does not control — the Falun Gong an example — and prohibits mixing religion and politics. That has led Fo Guang Shan to play down its message of social change and even its religious content, focusing instead on promoting knowledge of traditional culture and values. The approach has won it high-level support; President Xi Jinping is one of its backers. But its relationship with the party raises a key question: Can it still change China?

See Separate Article CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com

Giant Buddha-Building Craze in China

Zhou Mingqi wrote in Sixth Tone: “Is there such a thing as too many Buddhas? China may be about to find out. “For the past few decades, the country has been in the midst of a Buddha-building craze. Just last year, for example, it was reported that a wealthy businessman had nearly completed “the world’s largest copper sitting Buddha” in a remote county in the northern province of Shanxi. The 22-story structure supposedly took 8 years to build and cost 380 million yuan ($57 million) — a relative pittance in the world of big Buddhas. [Source: Zhou Mingqi, Sixth Tone, October 23, 2018. Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Lu Hua and Kilian O’Donnell]

“Travelers looking for the world’s largest Buddha statue, however, must make the trip to the neighboring province of Henan. Opened in 2008, the Spring Temple Buddha is located in Lushan County — one of the poorest counties in all of China, in which residents’ average annual discretionary income is just 12,800 yuan. In stark contrast to the poverty of the surrounding countryside, the Spring Temple Buddha, which took 11 years to complete, stands more than 208 meters tall, is plated with 108 kilograms of gold, and cost an eye-popping 1.2 billion yuan to build.

“Every few years, there are reports in Chinese media of another mammoth statue being unveiled. Cloaked in shining golden robes, massive Buddhas have become a fixture of China’s tourism industry, adorning temples, mountaintops, and lakes — wherever builders can find a spot with favorable feng shui. This obsession with monumental statuary isn’t limited to giant Buddhas, either. In recent years, numerous legendary and historical figures have been immortalized in larger-than-life forms, including Guan Yu, Laozi, Confucius, Huang Di, Yan Di, and Mazu. One village even built a giant, gold-plated statue of Mao Zedong.

“Wang Zuo’an, director of China’s National Religious Affairs Administration, admits that some Buddha builders are perhaps placing an undue emphasis on size. He describes their mindset as: “If someone else has the largest standing Buddha, then I’ll build the largest sitting Buddha. And if someone has already built the largest sitting Buddha, then I’ll build the largest reclining Buddha.”

“Those familiar with the Communist Party’s official stance on atheism may find it perplexing that local governments across China would approve the construction of enormous religious idols. Yet while these statues may be aimed at the country’s religious believers, their real purpose is far more worldly: making money. Put simply: If an area without any notable natural scenery or historical landmarks wants to attract tourists, it needs a gimmick — and giant Buddhas fit the bill nicely. They are also well-suited to China’s entrance fee-centric tourism industry: By the time visitors are in the gate and realize that, actually, one giant statue of the Buddha is much like the next, park authorities have already made all the money they expect to make.

Forces Behind the Buddha Building Craze in China

Zhou Mingqi wrote in Sixth Tone:“Buddhism in China has a long history.” Over the centuries” Buddhist statues, temples, and grottoes have sprouted up all over; and today, these heritage sites — including the 71-meter tall Leshan Giant Buddha, the Mogao Caves, and the Longmen Grottoes — are some of the country’s most well-known and popular tourism destinations. In an effort to compete with these sites, which have deep historical connections to the Buddhist tradition, officials and businessmen elsewhere have tried to one-up them with their own “world’s greatest” and “world’s largest” Buddha statues. [Source: Zhou Mingqi, Sixth Tone, October 23, 2018. Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Lu Hua and Kilian O’Donnell]

“The craze has its roots in the 1990s, in the success of some of the earliest monumental Buddha statues. In 1997, local officials in the eastern city of Wuxi unveiled the Lingshan Buddha. Standing 88 meters tall, it was then the world’s tallest Buddha statue — a title that was then still a novelty. It inaugurated a building frenzy.

“Perhaps sensing what was coming, in 1994 Zhao Puchu — the then president of the Buddhist Association of China — tried to head matters off by noting that the still-under-construction Lingshan Buddha gave China one giant Buddha for each cardinal direction: north, south, east, west, and center. “That's enough,” Zhao declared. “From now on, there is no need to build any more outdoor Buddha statues.”

Alas, his words fell on deaf ears. As did similar words from the State Council — China’s Cabinet — which that same year felt compelled to issue a “Notice to Stop the Overbuilding of Outdoor Buddha Statues.” The National Religious Affairs Administration and other departments also joined in, and have since spent the past few decades repeatedly stressing that regional Party and government leaders should not be supporting or involved in the building of unapproved temples or outdoor Buddha statues for any reason. Work has nonetheless continued around the country, and given that each statue takes years to build — and none of them are designed to be inconspicuous — it seems some local officials remain willing to look the other way.

“Yet the copycats all utterly fail to understand what made Lingshan so successful in the first place. Sure, it had a big Buddha, but those in charge also realized that the country’s increasingly discerning tourists cared about more than just size. In the years since the Lingshan Buddha was built, the park in which it resides has been expanded to include the Brahma Palace — a Buddhist art museum featuring the work of craftsmen from around the country that won the 2009 Luban Prize for architecture and engineering — and Nianhua Bay, a popular Buddhist-themed imitation ancient village that draws on elements of Tang Dynasty design and combines them with local styles.

“This additional work paid off, and now Lingshan draws more than 4 million tourists a year. It has also held the 2015 World Buddhist Forum. But imagine if local officials had been content with the Buddha statue alone. Would it still be such a draw, even after larger Buddha statues were built elsewhere? The success of the Lingshan Buddha has much to do with its location in the economically prosperous Yangtze River Delta and park officials’ willingness to try new ideas, not just its size. Meanwhile, Lushan has been home to the tallest Buddha statue in the world for a decade now, but many of the county’s residents remain mired in poverty.

Image Sources: Buddhism Today, Inside Tropical Island blog; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei\=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021