KUNG FU IN CHINA

”Kung fu” (“gong fu”) is a Chinese word that means "expertise." It is used in the West to describe a family of martial arts, whose weapon-based form, using swords and staffs, is known as wushu in China. Kung fu and wushu are considered a branch of qi gong.

”Kung fu” (“gong fu”) is a Chinese word that means "expertise." It is used in the West to describe a family of martial arts, whose weapon-based form, using swords and staffs, is known as wushu in China. Kung fu and wushu are considered a branch of qi gong.

Kung fu is believed to have its roots in India. The story goes it was developed by monks who restored their circulation after long periods of meditating by imitating animals and flying birds. It became a martial art when the movements were adapted by the monks into a form of combat used to protect the temple from intruders.

There are over 400 different kung-fu-style martial arts, both with and without weapons. Most were originally handed down through families and some still bear family names.

Kung fu and the Chinese martial arts were first brought to the attention of American audiences by the 1970s television series “Kung Fu”. Before that the most well known martial arts in the states — judo and karate — were from Japan. In the show David Carradine played Kwai Chang Caine, better known as Grasshopper. Stoic, deliberate, aloof and metaphorical no matter what was thrown at him, he delivered lines like “Let the passion pass through you like the wind” and “the warrior destiny is always a broken path” and fought with kind a dreamy style that was much slower and fluid than the frenetic almost slapstick style seen in many king fu movies.

In June 2009, Carradine was found dead in his room at the luxury Swissotel Nai Lert Park Hotel in Bangkok in an apparent suicide. An investigator told AP: “I can confirm we found his body naked, hanging in the closet.” Carradine’s cause of death was listed as “autoerotic asphyxiation.”

There are two main general kung fu forms: the southern style and northern style. Southern Chinese kung fu forms such as “hop gar” and “hung gar” kung fu are like what Jackie Chan does in his movies. Hung gar kung fu is often called "five animal" kung fu because its movements are like those of five animals: the tiger, snake, leopard, crane and dragon. People often like southern Chinese styles more than northern Chinese styles because they look quicker and more powerful.

See Separate Articles: WUSHU, TAI CHI AND THE MARTIAL ARTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; SPORTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SHAOILIN TEMPLE, ITS FIGHTING MONKS AND SACRED MOUNT SONG factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND WUXIA (CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION) factsanddetails.com ; MARTIAL ARTS FILMS: WUXIA, RUN RUN SHAW AND KUNG FU MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; BRUCE LEE: factsanddetails.com ; JACKIE CHAN factsanddetails.com ; JET LI factsanddetails.com

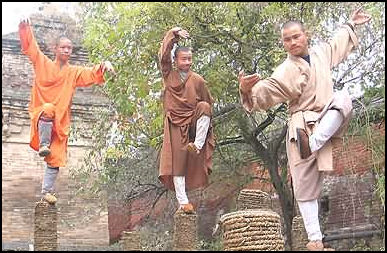

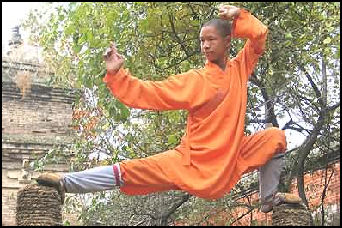

Kung Fu Moves

Kung fu emphasizes lightning reflexes and elastic flexibility. It uses movements similar to those in tai chi, many of which are named after animals: the praying mantis, monkey style, or white crane style. Unlike Japanese karate and Korean tae kwon do movements, which tend to be straight ahead and direct, kung fu and judo movements tend to be circular and "gentler." The combative forms of kung fu incorporate clawing, standing blows as well as direct Karate-like hand and foot blows.

Kung fu emphasizes lightning reflexes and elastic flexibility. It uses movements similar to those in tai chi, many of which are named after animals: the praying mantis, monkey style, or white crane style. Unlike Japanese karate and Korean tae kwon do movements, which tend to be straight ahead and direct, kung fu and judo movements tend to be circular and "gentler." The combative forms of kung fu incorporate clawing, standing blows as well as direct Karate-like hand and foot blows.

The main divisions of kung fu and the numerous subdivisions favor certain kinds of blows and movements, training methods and attitude. The southern styles emphasize strength, power, hand conditioning and kicks. The northern style employs softer, slower movements that stress the lower body, graceful-ballet-like movements, agile foot techniques and hand blows delivered in combinations. The Shaolin school emphasizes working in a small space, keeping movements compact.

Kung Fu and Shaolin Temple

What is generally regarded as kung fu today is the martial art originally practiced at Shaolin Temple — a temple founded in the Songshan mountains in Henan province in China 1,500 years ago. The film “Shaolin Temple” (1982) with Jet Li, one of the most popular kung fu films ever, helped put Jet Li and Shaolin Temple on the on the map.

Shaolin kung fu was founded, Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic, “by monks who had committed their lives to perfecting kung fu styles with names like Plum Flower Fist and Mandarin Duck Palm, each a symphony of physical movements, adding variation upon variation that pushed human muscles and bones to their limits. Some would say beyond their limits.” [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

Shaolin is not only the birthplace of kung fu it also a place of importance in the history of religion in China. In A.D. 527, an Indian monk named Bodhhidarma founded the precursor of Zen Buddhism after spending nine years staring at a wall and achieved enlightenment. He also is credited with creating the basic movement of Shaolin kung fu by imitating the movements of animals and birds.

How did kung fu evolve and how did a supposedly peace-loving Buddhist sect became involved with the martial arts? Scholars speculate that monks learned to defend themselves at time when banditry was rampant and there was a lot of fighting between local warlords. The origins of kung fu are somewhat murky. There are accounts in ancient texts of monks performing feats of physical skill and strength such as two-finger handstands, breaking iron blades with their heads and sleeping while standing on one leg.

Pagoda Forest at Shaolin-Temple

Shaolin Temple became associated with martial arts in the 7th century when 13 Shaolin monks, trained in kung fu, rescued prince Li Shimin, the founder of the Tang dynasty. After that Shaolin expanded into a large complex. At its peak it housed 2,000 monks. In the 20th century it fell on hard times. In the 1920s, warlords burnt down much of the monastery. When the Communists came to power in 1949, Buddhism, like other religions was discouraged. Land owned by the temple was distributed among farmers. Monks fled.

Many of the temples that remained at Shaolin in the 1960s were destroyed or defaced during the Cultural Revolution. All but four of the temple's monks were driven off by the Red Guards. The remaining monks survived by making their own tofu and bartering it for food. In 1981 the 12 elderly monks at the temple spent much of their time farming. Their religious activities were performed discretely or in secret.

The film “Shaolin Temple” remains one of the most popular kung fu films ever. After its success the government and entrepreneurs realized there was money to made exploiting the temple. Old monks were asked to come back and new ones were recruited. Today about 200 studentsing study directly with the masters who live in the temple. Many take a vow of chastity but they are forbidden from receiving “jie ba”, a kung fu ritual in which scars are made on the head and wrist with burning incense.

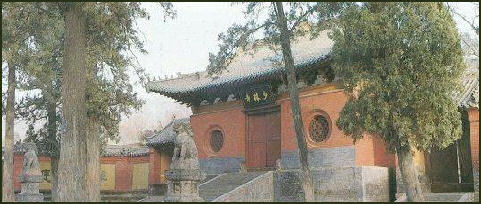

Shaolin Temple

Shaolin Temple lies in a valley just over the Song Mountains. Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic, “Shaolin Temple has helped foster an undeniable kung fu renaissance, which has coincided with China's own resurgence as an international power... Tour buses disgorge their daily load of visitors at the Shaolin Temple. They come from all over the People's Republic — uniformed soldiers on leave, businessmen on junkets, retirees on package holidays, young couples leading wide-eyed children kicking and chopping the air with exuberant expectation. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

Shaolin Temple is the birthplace of China's greatest kung fu legend. Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “Here, the popular myth holds, is where a fifth-century Indian mystic taught a series of exercises, or forms, that mimicked animal movements to the monks at the newly established Shaolin Temple. The monks adapted the forms for self-defense and later modified them for warfare. Their descendants honed these "martial arts" and over the next 14 centuries used them in countless battles — opposing despots, putting down rebellions, and fending off invaders. Many of these feats are noted on stone tablets in the temple and embellished in novels dating back to the Ming dynasty. [Ibid]

“Scholars dismiss much of this as legend embroidered with bits of truth,” Gwin wrote. “Bare-handed martial arts existed in China long before the fifth century and likely arrived at Shaolin with ex-soldiers seeking refuge. For much of its history, the temple was essentially a wealthy estate with a well-trained private army. The more the monks fought, the more proficient they became as fighters, and the more their fame grew. Yet they were not unbeatable. The temple was sacked repeatedly during its history. The most devastating blow came in 1928, when a vengeful warlord burned down most of the temple, including its library. Centuries of scrolls detailing kung fu theory and training as well as treatises on Chinese medicine and Buddhist scriptures — essentially the temple's soul — were destroyed, leaving the legacy of Shaolin kung fu to be passed down master to disciple. [Ibid]

Shaolin Temple

Shaolin Temple Commercialism

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic, “Temple officials seem more interested in building the Shaolin brand than in restoring its soul. Over the past decade Shi Yongxin, the 45-year-old abbot, has built an international business empire — including touring kung fu troupes, film and TV projects, an online store selling Shaolin-brand tea and soap — and franchised Shaolin temples abroad, including one planned in Australia that will be attached to a golf resort. Furthermore, many of the men manning the temple's numerous cash registers — men with shaved heads and wearing monks' robes — admit they're not monks but employees paid to look the part. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

Yongxin told National Geographic that all of his efforts further Buddhism. "We make more people know about Zen Buddhism," he says. A slightly jowly, sad-eyed man, he has a politician's gift for imbuing his remarks with the sense that he believes deeply in what he's saying. "By registering the Shaolin brand name in other countries, promoting Shaolin traditional cultures, including kung fu, we're having people around the world know better and believe in Zen Buddhism." [Ibid]

Yongxin isn't the first abbot to face criticism that Shaolin has pursued riches over enlightenment. A 17th-century magistrate railed against the temple's "lofty mansions and splendid furnishings."

Shaolin Temple Schools

On the kung fu schools in Dengfeng, Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “These schools fill their ranks with boys, and increasingly girls, from every province and social class, ranging in age from five to their late 20s. Some arrive hoping to become movie stars or to win glory as kickboxers. Others come to learn skills that will ensure good jobs in the military, police, or private security. A few are sent by their parents to learn discipline and hard work. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

“Six days a week, 11 months of the year, the campuses come alive at dawn with legions of students dressed in identical tracksuits — hundreds of children born in the new China, aligned in sharp rows, practicing kung fu. Faces forward, backs rigid, they punch and kick in unison, their voices puncturing the morning air as they repeat their instructors' cadences. [Ibid]

“At night his students sleep in unheated rooms. No matter the temperature, they train outside, often before sunrise. They jab tree trunks to toughen their hands and practice squatting with other students sitting on their shoulders to build leg strength. Within a month of arriving, new students are expected to be able to do full splits. During drills, coaches use bamboo staffs to swat the hamstrings of any boy whose form is not perfect or whose effort is deemed insufficient. “Asked if such harsh treatment could yield angry students, teacher named Hu Zhengsheng, told National Geographic, "It is eating bitterness. They understand it makes them better." [Ibid]

Shi Dejian

Hu found his small kung fu school in 2003 in a few cinder-block buildings just outside Dengfeng. Unlike the big kung fu academies, which stress acrobatics and kickboxing, Hu teaches his 200 boys and a few girls the traditional Shaolin kung fu forms. Gwin wrote: “From his own experience Hu knows that a boy's idea of kung fu can change as he matures. When he was young, he was obsessed with kung fu films, absorbing the performances of Bruce Lee and Jet Li and fantasizing about taking revenge on bullies in his village. At age 11 he managed to talk his way into the Shaolin Temple, where he became a servant to the coach of one of the performance troupes. [Ibid]

As Hu is telling his story, Gwin wrote, “a boy dressed in the school's dove gray robes and sneakers appears at the office door to report that a student has twisted an ankle. By the time Hu arrives to check on him, the injured pupil has resumed practice, gritting his teeth as he kicks a heavy bag. Hu nods with a teacher's satisfaction. “He is learning to eat bitterness." [Ibid]

“Hu's problem has not been students leaving so much as getting enough new enrollees to keep up with the school's costs. Many of the boys come from poor families, and Hu charges them only for food. Unlike the big schools, he refuses to give kickbacks to taxi drivers who troll the Dengfeng bus station for newly arrived prospective students. Gradually, however, he has accepted the teaching trends and has begun offering a few courses in kickboxing and the acrobatic kung fu forms, hoping to attract new students and then sway them to the traditional forms. [Ibid]

See Places, Shaolin Temple

Fighting Kung Fu Versus True Shaolin Kung Fu

Hu Zhengsheng, who runs a martial arts school near Shaolin, was offered a lead role in a kung fu movie by a Hong Kong producer. Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “It's easy to see why. Hu has a boyishly handsome face and projects a confidence won through years of physical and mental testing. Yet he isn't sure whether to accept the offer. He doesn't agree with how kung fu usually is portrayed in the movies — a mindless celebration of violence that ignores the discipline's key tenets of morality and respect for one's opponent. He is also concerned that Yang Guiwu's other disciples will lose respect for him if he becomes an entertainer. And he worries about the trappings of fame. His master had admonished him to remain humble, even as he surpassed the students around him. Humility defeats pride, Master Yang had preached. Pride defeats man.” [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

Fighting is not the most important lesson of kung fu, Hu explains. His focus is on honor. The skills he is passing on to his charges come with great responsibility. In each boy he looks for respectfulness and a willingness to "eat bitterness," learning to welcome hardship, using it to discipline the will and forge character. “When he met his master he said ‘I already had memorized many traditional forms, but he taught me the theory behind the moves. Why you must flex your arm a certain way. Why your weight must be on a certain part of your foot." He stands up to demonstrate. A fist strike, he explains, is delivered like a chess move, anticipating a range of possible countermoves. "No matter how my opponent responds, I am prepared to block and deliver a second, third, and fourth blow, with each aimed at a pressure point." He pantomimes the moves in slow motion. "A student can learn this in a year," he says. "But to do it like this" — his hands and elbows become a blur as he repeats the moves at full speed — "takes many years." The difference, he says, is making the moves instinctive and delivering each with precision and maximum power to the weakest points of an opponent's defenses. [Ibid]

Jin Yong, father

of martial arts fiction,

See Literature "There are no high kicks or acrobatics," he says. Such moves create vulnerable openings. "Shaolin kung fu is designed for combat, not to entertain audiences. It is hard to convince boys to spend many years learning something that won't make them wealthy or famous." He seems drained by the thought. "I worry that is how the traditional styles will be lost." Often, the first thing students learn is how to breath properly. Hu said he was taught that breathing was elemental to harnessing one's chi, or life force. His master taught him breathe in through the navel, out through the nose. Steady, controlled, in harmony with your heartbeat and the rhythms of your other organs. Learning to breathe properly, he told them, was the initial step on the arduous path to tapping the wellspring of the chi's power and, in doing so, unlocking one of the universe's hidden doors. [Ibid]

When asked about kung fu’s violent side and the nonviolent principles of Buddhism, a Buddhist monk and kung fu master named Dejian said, in essence kung fu is about converting energy to force. Absent an adversary, the practice is a series of movements. The practitioner's own physical and mental weaknesses become his adversary. In effect, he goes to war with himself and emerges better than he was before. "In this way," says Dejian, "kung fu is nurturing." he said there are three principles at the root of the Shaolin Temple's guiding philosophy and for living a healthy life: chan (Zen meditation), wu (martial arts), and yi (herbal medicine).These are the same three principles at the root of the Shaolin Temple's guiding philosophy, he tells me. [Ibid]

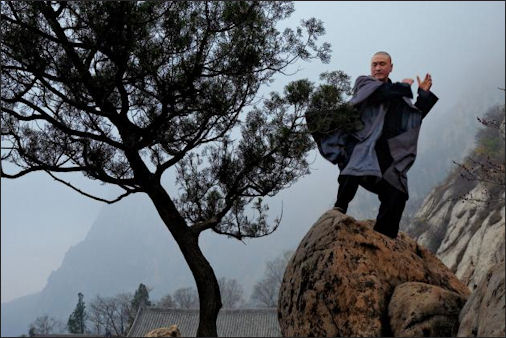

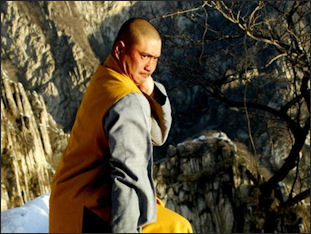

Shaolin Monk Who Practice Kung Fu on Cliffsides

Shi Dejian is a 47-year-old Buddhist monk who lives on an isolated mountaintop above the Shaolin Temple. week. To reach the monastery where he lives one has to trek up the vertiginous series of switchbacks hacked into the granite mountainside. Despite his isolation a lot of people go through great lengths to seek him out. Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic, a television crew had trekked up granite mountainside with “a professional mixed-martial-arts fighter, whom they planned to film testing his skills against the monks. (He went home bruised.) A neurology team from Hong Kong University had arrived to study the effect Dejian's rigorous meditation regimen has on his brain activity, and he had spent an exhausting night applying his chi techniques to ease the pain of an ill friend. Then there had been the Communist Party official from Suzhou who had barged through the gate and demanded a cure for his brother's diabetes. For a man who seeks solitude, Dejian finds himself inundated with people.” [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

book by Jin Yong Dejian owes this parade of strangers largely to Internet video clips that show him demonstrating traditional Shaolin kung fu forms, often while balancing atop needlelike precipices or on the sloping roof of his cliffside pagoda, one misstep from a fatal fall of several hundred feet. The clips, most taken by visitors over the years, have spread among sites devoted to kung fu and Chinese medicine...And though he doesn't say it, these are the principles that the temple's many critics, both inside and outside China, say have been neglected in the pursuit of commercial deals and tourist dollars. The message of his death-defying performances seems to be one of authenticity: When you practice true Chan Wu Yi, this is what is possible. [Ibid]

“Face-to-face, Dejian looks like a sort of mountain elf, standing a few inches over five feet tall with a thick, muscular build. He wears a long wool cape and a round, Mongolian-style hat to protect his shaved head from the cold mountain air and prefers to talk while in motion, replanting a young cedar tree or plucking dandelion leaves for a salad. His frequent laughter hints at an impish rather than a pious spirit. His path to this Song peak began in 1982, when, as a 19-year-old kung fu prodigy, he left his family's home not far from the Mongolian border and made a pilgrimage to the Shaolin Temple. His search for kung fu teachers led him to Yang Guiwu, and he soon distinguished himself as the master's best student. The more he learned about kung fu, the more he became interested in its intersection with meditation and Chinese medicine, and he finally decided to take the monastic vows at the Shaolin Temple. [Ibid]

As the tourist crowds steadily grew in the early 1990s, Dejian increasingly sought seclusion, often camping near the ruins of a small temple on a nearby mountain peak. The oldest monks, disheartened by Shaolin's expanding commercial ventures, encouraged Dejian to establish the old temple as a retreat focused on Chan Wu Yi. He recruited local masons to quarry granite blocks out of the rock faces, and he and his disciples hauled bags of cement and roof tiles up to the site. Slowly they have transformed the crumbling temple into a complex of pagodas that appears to cling to the steep mountainside. It is a setting that evokes a meditative calm. Pockets of thick fog get trapped along the ridgelines, magpies nest among the outcrops, and springs intermittently spray over the rocks. The only human sounds are the constant tink, tink, tink of the masons' chisels ringing in the chill air. [Ibid]

Daily Life of Kung Fu Master

book by Jin Yong Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic, “Dejian and his disciples tend small groves of bamboo and terraced plots of vegetables and herbs. They adhere to a vegetarian diet and harvest wildflowers, mosses, and roots to make medicines for everything from insect bites to liver problems. People come from all over China seeking advice for various ailments. Usually they want treatment only for symptoms, says Dejian, but "Chan Wu Yi treats the whole person. When the person is healthy, the symptoms disappear." [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

His habit is to rise at 3 a.m., first meditating, then practicing breathing techniques designed to strengthen the chi. There was a time when he would spend six hours or more practicing traditional kung fu forms every day, but now he is pulled by some of the same modern forces that are reshaping the Shaolin Temple. Responding to requests to lecture, raising money to finish the construction, training his disciples, and of course attending to the stream of visitors — all compete for his attention and energy. [Ibid]

"But I am always practicing kung fu," he says. He grabs my hand and puts it on one of his immense quadriceps. I can feel him pulsing the muscle. Then he moves my hand to a shot-put-like calf. More pulsing. "I do this all day," he says, explaining that he incorporates kung fu moves into all sorts of daily activities, from pulling weeds to climbing the mountain. [Ibid]

“On the last morning I spend at his retreat,” Gwin wrote, “Dejian shows me his private quarters, a tiny stone cupola perched on the tip of a sheer cliff. He leads the way out to a terrace with a view of the deep, bowl-shaped valley carpeted with thick pine forests. A weather front is blowing in, and his thick wool cape flutters behind him. Without warning he jumps up onto the low wall bordering the lip of the cliff, the wind filling his cape so that it flows out over the void. I suddenly feel guilty, that I somehow prodded him onto the ledge, like a morbid voyeur. I hadn't consciously considered it before, but of course that's why many people come up to see Shi Dejian, to watch him challenge death. Maybe this time death wins. But standing on the ledge, he smiles at me. "You are afraid?" he asks, seeing the look on my face. "Kung fu is not only training the body; it is also about controlling fear." He hops lightly from one foot to the other, lunging, punching, spinning, each step inches from a horrifying fall. His eyes widen as he concentrates. The cape billows and snaps in the cold wind. "You cannot defeat death," he says, his voice rising over the wind. He kicks a foot out over the abyss, balancing on one of his tree-trunk legs. "But you can defeat your fear of death." [Ibid]

Sometimes the adversary isn't absent. Not everyone who comes up the mountain is a friend, and Dejian has survived attempts on his life. A few years ago, as he was returning up the mountain path, four men jumped him, attempting to push him off a ledge. They possessed advanced kung fu skills, but he quickly fought them off. It is a subject he chooses not to discuss, but others confirmed the incident. "The Song Mountains are full of kung fu rivalries," a Dengfeng official told me, "just as they have been for centuries." [Ibid]

Death of a Great Kung Fu Master

Shi Dejian Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic “The master spent his last day of life wrapped in a quilt stitched by his wife, his rasping, irregular breaths filling the small bedroom. Throughout the cool spring day a stream of visitors arrived...to pay their respects at the deathbed of Yang Guiwu, the man who had taught them kung fu. Some wore monks' robes and offered blessings as they entered the tiny brick house. Others wore jeans and loafers and stubbed out cigarettes before passing through the door. The master's wife, her white hair neatly combed, clasped the shoulders of each new arrival as if he were a blood son and ushered him through her kitchen, past the coal-burning stove, to join family members and other disciples assembled at her husband's bedside. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic March 2011]

“The wife leaned close to the bundled figure to announce a visitor, the last disciple the master had accepted into his kung fu family 15 years before. “It's Hu Zhengsheng,” Hu, now a broad-shouldered man of 33, bent over the shriveled figure. “shifu,” he called softly, respectfully, using the Mandarin word for teacher. “Can you hear me?” The old man's eyelids, pale and thin like rice paper, flickered. For an instant, his pupils seemed to center on the young man's face, then drifted away. [Ibid]

“Many times the master had told Hu about awakening from dreams in which his martial arts ancestors, long-dead monks from the Shaolin Temple, visited him. They came bearing wisdom collected over centuries from generations of men whose feet had grooved the flagstones in the temple's training hall, whose bones were interred in the Pagoda Forest just outside the temple walls....The master's most advanced disciples recognized special irony in the fact that the old man's lungs would ultimately betray him. He would have approved of this turn of life's wheel, a final lesson in humility for the man who had instructed that breathing was elemental to harnessing one's chi, or life force....Now, with or without unseen spirits at his side, Yang Guiwu stood at another of the universe's hidden doors. The disciples listened for signs in his breathing that he was trying to marshal his life force for the journey ahead. [Ibid]

“Soon after Hu Zhengsheng visited his bedside, Yang Guiwu passed into the afterlife. Dozens of former students gathered with his family and neighbors at the small house in Yanshi, which had been adorned with dozens of brightly colored paper wreaths. The hiss and pop of fireworks filled the air, alerting the spirit world to the master's arrival. A trio of flute players led the funeral procession out of town to the family's wheat field, where the master would be buried beside his parents. The mourners filed carefully between the muddy rows of lustrous green wheat, careful not to trample the young crop. [Ibid]

Rebirth of Bruce Lee's Wing Chun Kung Fu Style

Shi Dejian In December 2011, AFP reported: “Sam Lau picks up his sword and waves it in a series of terrifying slashes as he runs towards a student, who retreats laughing nervously. All around them, kung fu students grapple fiercely. The pupils have come to Lau's Hong Kong studio — some from as far away as Italy — to hone their moves in the kung fu style called wing chun, which is on the rise again decades after the death of its most famous follower, Bruce Lee. [Source: AFP, December 5, 2011]

Many credit wing chun's renewed popularity to a series of films about Yip Man, one of the art's greatest "sifus", or teachers, and most famously the man who turned Lee from street fighter to martial arts legend. "I started to learn wing chun because of the movie 'Ip Man'. He was a great person," said Sam Ng, 12. "When Yip Man saw someone beating someone else, he would stand up and help to rescue them." Ng shows off a series of sharp chopping gestures followed by a formal bow.

But though students may be brought to wing chun by the 2008 blockbuster starring Donnie Yen -- or its sequel and prequel -- it is the health and self-defence benefits that keep them sparring, said Yip's son, Yip Ching, 77. "Yip Man let the world know about wing chun but it's even more popular now," he said. Lau, 64, was once Yip's assistant and is now a sifu in his own right with over 1,000 pupils. He says that wing chun appeals to a broad range of students because of its emphasis on cunning and focus rather than brute force. "I like it because now I am not shy," an Italian student said. "Before, I was shy, but now I have found a different part of myself. I have more positive energy."

Lau also credits the growth in student numbers to the Internet, which allows would-be martial artists to instantly find Yip's followers and their kung fu schools rather than what he sees as cheap imitations. "Wing chun is the best kung fu in the world, and we have to tell the world, this is the correct wing chun," he said. "People see my website, they say this is very good, this is Bruce Lee again." But exact numbers of wing chun students around the world are hard to come by, and this, says Lau, is a symptom of wing chun's problems.

Wing Chun Style of Kung Fu

book by Jin Yong According to legend the wing chun style of kung fu was founded by Yim Wing Chun, a young woman in southern China during the Qing dynasty who used techniques taught to her by a nun to overcome a local warlord trying to trap her into marriage. Yip Man brought her art to Hong Kong and, through Bruce Lee and the heyday of Hong Kong film, to the attention of the world."A lady in a dangerous situation can do something very serious, very fierce -- attack the eye, the chin, the neck -- wing chun is real fighting, real defence that relies on your technique," Lau said. [Source: AFP, December 5, 2011]

Fortunately, Lau's studios in Hong Kong's teeming Tsim Sha Tsui are free of pupils gouging one another's eyes out. Instead they stand in pairs grappling with their arms in an exercise called chi sao, or "sticky hands" -- a key element of wing chun in which students learn to respond instantly to an opponent's movements.Other exercises involve kicks and punches, while students may also train with wooden dummies and, in advanced stages, poles or swords.

Students learn to outwit opponents with speed and deliver multiple punches in quick succession while staying balanced around a centre line. The most important exercises are not the most spectacular, but Lau's students say they train the body to react faster than the brain.They also lead to a different state of mind and body in which relaxation enables total focus, says Lau's disciple, Italian Furio Piccinini.

"Even when punching incredibly fast you have to also be relaxed... Normally you think that to punch you use force, but that's not true, you use the body weight to punch and to develop power," Piccinini said. "If you are relaxed, you can develop great power. I think that's incredible -- it's like geometry, physics. With a simple movement you can push very, very hard."

With roots in down-and-dirty street fighting, the sport has no standardised system of exams and competitions, and lacks the international profile of other martial arts like judo and taekwondo. Lau sees it as his mission to "unify wing chun" to preserve Yip Man's techniques for the future. "I have been asking the Chinese government to promote wing chun, to develop it and tell the world to follow," he said. "But they only know about gold medals and the Olympic Games. With several teachers claiming to be the heirs of Yip Man, Lau's quest to become the head of a united wing chun movement may prove difficult.

The crowd that gathers at Yip's grave for an autumn commemoration shows the old man is far from forgotten. Some European visitors have no language in common with Yip's local fans, but all rowdily honour him with incense, rice wine and a whole barbecued pig. One Hong Kong disciple, Tony Ng, has only been learning for a year but sees wing chun featuring heavily in his future. "I'm learning to use my whole body for fighting," he said. "It's very easy to say but very difficult to do."

Image Sources: Amazon, Beifan.com, Kung Fu Daily, Erzine Mark, clip from German National Geographic video

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2011