WUXIA (CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION)

Wuxia, which literally means "martial heroes", is a genre of Chinese fiction involving the adventures of martial artists in ancient China. Although it has traditionally been a form of fantasy literature, it is popular that it has been adapted to opera, television series, many famous Kung Fu movies and even video games. The word wuxia is a compound wu ("martial", "military", or "armed") and xiá ("chivalrous", "vigilante" or "hero"). Practitioners of the code of xia is often referred to as a xiákè ("follower of xia") or yóuxiá ("wandering xia"). In some translations, the martial hero is called a "swordsman" or "swordswoman" even though he or she may not necessarily wield a sword. [Source: Wikipedia]

The heroes in wuxia fiction typically do not serve a lord, wield military power, or belong to the aristocratic class. They often originate from the lower social classes of ancient Chinese society. A code of chivalry usually requires wuxia heroes to right and redress wrongs, fight for righteousness, remove oppressors, and bring retribution for past misdeeds. Chinese xia traditions can be compared to martial codes from other cultures, such as the Japanese samurai bushidō.

With the help of martial arts films and Chinese fantasy and martial arts literature translation websites such as wuxiaworld.com, Chinese martial arts fiction is reaching a broader non-Chinese audience and more approachable to people in the West. Formally obscure martial arts terms such as “yinyang”, “neigong” and “qi” are already familiar to veteran foreign readers of the genre.

“Jianghu” is a an important concept in Chinese martial arts novels. British-Swedish translator Anna Holmwood, known for translating the works of Jin Yong, told the Global Times: "I tackled it [jianghu] as a constellation of terms that includes wulin [the world of martial arts] and xia [a core spirit of martial arts that promotes actions of integrity to stand up for the weak against bullies. On the one hand, jianghu [rivers and lakes] refers to a concrete place, the landscape of southern China, where historically the instruments of the Chinese imperial government haven't been able to penetrate as deeply." [Source: Huang Tingting, Global Times, November 9, 2017]

“"Knowledge is getting deeper all the time,” Holmwood told the Global Times. “Moreover, "there are martial arts clubs in small towns all across Europe and America and further afield, so in fact there is a big interest in the West not only in watching and reading about martial arts, but also practicing it," she wrote. "Chinese martial arts celebrates the power of the individual to do good in much the same way as Western stories of heroism do, this is the essential connection that makes” wuxia “stories universal across cultures," she noted.

"The sheer complexity and difficulty of Jin Yong's work means that something like this [English translation of the novel] takes a lot of time," translator Anna Holmwood wrote. While the market potential for Chinese martial arts is growing, "in terms of book publishing this is relatively new thing," Holmwood wrote. "Therefore, all involved are determined to do our best. We are all hopeful that it will strike a chord with readers." [Source: Huang Tingting, Global Times, November 9, 2017]

See Separate Articles: WUSHU, TAI CHI AND THE MARTIAL ARTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; SHAOILIN TEMPLE, ITS FIGHTING MONKS AND SACRED MOUNT SONG factsanddetails.com ; KUNG FU IN CHINA, SHAOLIN TEMPLE AND BRUCE-LEE-STYLE KUNG FU factsanddetails.com JIN YONG AND WUXIA (CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION) factsanddetails.com ; MARTIAL ARTS FILMS: WUXIA, RUN RUN SHAW AND KUNG FU MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; BRUCE LEE: factsanddetails.com ; JACKIE CHAN factsanddetails.com ; JET LI factsanddetails.com; MODERN CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JOURNEY TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com ; ROMANCE OF THE THREE KINGDOMS factsanddetails.com ; BATTLE OF RED CLIFFS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA AND THEATER factsanddetails.com ; PEKING OPERA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) mclc.osu.edu; Classics: Chinese Text Project ; Side by Side Translations zhongwen.com; Classic Novels: Journey to the West site vbtutor.net ; English Translation PDF File chine-informations.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Hero Born”: The Definitive Edition Book 1 of 4: Legends of the Condor Heroes by Jin Yong, Carolyn Oldershaw, et al. Amazon.com; “Legends of the Condor Heroes Series 4 Books Collection Set By Jin Yong (A Hero Born, A Bond Undone, A Snake Lies Waiting, A Heart Divided)” by Jin Yong Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Fantasy Genres: a Primer for Wuxia, Xianxia, and Xuanhuan” by Jeremy Bai Amazon.com; “Wuxia, 88 Tales of Chinese Chivalry and Martial Arts: Translations from the Classics” by Hwong Seng | Amazon.com; “Sword of Sorrow, Blade of Joy” Book 1 of 4: Tales of the Swordsman | by JF Lee and Double Happiness Publishing Amazon.com; Wuxia Films: “Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition” by Stephen Teo Amazon.com; “Chinese Martial Arts Film and the Philosophy of Action” by Stephen Teo Amazon.com; “100 Greatest Hong Kong Action Movies” by David Rees Amazon.com; “It's All About the Style: A Survey of Martial Arts Styles Depicted in Chinese Cinema” by Blake Matthews , Nathan Shumate, et al Amazon.com; “Bruce Lee: Fighting Spirit” by Bruce Thomas, the bassist in Elvis Costello’s group The Attractions Amazon.com; Jackie Chan Autobiography:“I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action” Amazon.com; “Legacies of the Drunken Master” by White Amazon.com; “New Essential Guide to Hong Kong Movies” by Rick Baker , Kenneth Miller, et al. Amazon.com; “Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Make Them” by an enthusiastic book by Stefan Hammond (Contemporary Books, 2000) Amazon.com

Development of Martial Arts Fiction

The popularization of martial art fiction took place at the end of the 19th century and early 20th when modern printing techniques were first being widely employed yet village and neighborhood storytellers were still popular performers. Paize Keulemans suggests that the martial arts genre was influenced by technique used by storytellers. In a review of the book, “Sound Rising from the Paper” by Keulemans, Mengjun Li writes: Keulemans first “establishes the cultural, historical, and technological contexts” with a “detailed examination of the acoustic features of martial arts novels. Chapter 1 examines the Ming and Qing literati’s interests in oral storytelling and their varied ideological motivations. In it, Keulemans compares Yu Yue’s 1889 editing of The “Three Knights and Five Gallants” into “The Seven Knights” with earlier scholars’ textual engagement with the storyteller’s oral performance. For late-Ming and early-Qing scholars such as Jin Shengtan, emphasizing the storyteller figure’s marvelous ventriloquistic skills of sound-making enabled the fiction writer to call attention to the illusionistic nature of the performer’s voice and, more important, “to the fictional qualities of the vernacular text itself”. By appreciating the storyteller’s voice in the late Qing, Yu Yue “places himself in a long textual lineage of the cultural elite’s patronage of the vernacular arts”. [Source: Mengjun Li, University of Puget Sound, MCLC Resource Center Publication, November, 2016; Book: “Sound Rising from the Paper: Nineteenth-Century Martial Arts Fiction and the Chinese Acoustic Imagination” by Paize Keulemans (Harvard University Asia Center, 2014)]

“Keulemans points out that only two decades after Yu Yue’s creation of The Seven Knights martial arts novels began to be sold in “hastily and shoddily produced cheap imitations” using newly imported Western printing techniques, and were consumed by a broad “middlebrow audience of readers”. This link between the popularity of cheap printed editions and the middlebrow status of their readership in the early twentieth century is important. Robert Hegel has discussed the decline of fiction’s status in the Qing based on the shoddy quality of most Qing fiction editions. Indeed, a large number of vernacular novels were mostly, if not exclusively, circulated in these more affordable inferior quality woodblock editions in the Qing.

“While Yu Yue’s edition of The Seven Knights appealed to southern literati sentiments, Keulemans finds that the turning of storyteller tales into printed novels, which preceded Yu’s project in Beijing, capitalized on the popularity of the storyteller familiar to the local audience. By associating the novels with the reputed storyteller Shi Yukun in prefatory materials and foregrounding “the oral nature of the original telling,” the author is able to “suggest the kind of organic, oral community that is replaced by the printed tale”. In the printed novels, the oral storyteller continues to function “as a locus of folkloric authenticity in an increasingly modernizing world”. However, as Keulemans notes, when these novels were printed outside of Beijing in large quantities of inferior quality with new technologies of lithography and metal printing, they lost their folkloric authenticity. Nonetheless, the storyteller figure continued to be employed by writers for a variety of purposes. As such, these two chapters illustrate the cultural and historical significance embodied in the acoustic “excitement” of martial arts fiction.

Keulemans does “the first in-depth study of the use of onomatopoeia in the Chinese novel. He suggests that this literary technique should be considered “the novelists’s invention” and that “onomatopoeia turns the reading of fiction into a lively and suspenseful experience” of spectacle. These new findings complicate the accepted understanding of martial arts fiction readers and their reading habits, one that emphasizes the change from oral to silent reading in the late imperial period.

The book “also examines the early development of fiction serialization, which occurred when “the production of sequels took a decidedly more commercial turn” in the nineteenth century. “Chapter 5 takes up Keulemans’s third line of inquiry, the folkloric, examining the dialect elements in “The Three Knights and the Five Gallants” and “Tale of Romance and Heroism”. Investigating the skill of cross-talking, Keulemans demonstrates how writers and readers relied on their “distinction from and skillful imitation of provincial speech” to create a community, one built on a shared cosmopolitan identity.

Book: “Sound Rising from the Paper: Nineteenth-Century Martial Arts Fiction and the Chinese Acoustic Imagination” by Paize Keulemans (Harvard University Asia Center, 2014)

Martial Arts Novelist Jin Yong

Jin Yong (1924-2018) is arguably the most widely read author in the Chinese-speaking world and perhaps China's most popular writer. He wrote lengthy kung-fu fantasies and was China's most popular writer of the Martial Arts (Wuxia) genre. Born in mainland China, Cha moved to Hong Kong when he was 24 and started his career as a journalist and co-founded the Hong Kong daily newspaper Ming Pao Cha’s works have sold more than 300 million copies worldwide. Perhaps a more than a billion have been sold if you include all the copied and counterfeit versions that have been in circulation. Many of his novels were adapted into films and television programs as well video and online games. He is best known for his martial arts fiction series The Condor Trilogy. [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Jin Yong is the pen name of Dr. Louis Cha Leung-yunk. It can plausibly be argued that he popularized the tradition of kung fu fighters that became a fixture of Hong Kong and Chinese films and eventually made their way to Hollywood. Jin was greatly influenced by Li Zongwu, a writer emphasized the dark side of Chinese society, the one that despite the official probity hides the fact that many people have a “lian hou xin hei “(“thick-skinned face and black heart”, ie, are shameless and harbor evil intentions). Not every one is a fan. Wang Shou accused him of being a awful writer and said he had to "hold his nose" when he read Jin's work.

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker around the time he died: Louis Cha, who is ninety-four years old and lives in luxurious seclusion atop the jungled peak of Hong Kong Island, is one of the best-selling authors alive. Widely known by his pen name, Jin Yong, his work, in the Chinese-speaking world, has a cultural currency roughly equal to that of “Harry Potter” and “Star Wars” combined. Cha began publishing wuxia epics — swashbuckling kung-fu fantasias — as newspaper serials, in the nineteen-fifties. Ever since, his fiction has kept children, and their parents, up past their bedtimes, reading about knights who test their martial-arts mettle with sparring matches in roadside ale-houses and princesses with dark secrets who moonlight as assassins. These characters travel through the jianghu, which literally translates as “rivers and lakes,” but metaphorically refers to an alluvial underworld of hucksters and heroes beyond the reach of the imperial government. Cha weaves the jianghu into Chinese history — it’s as if J. R. R. Tolkien had unleashed his creations into Charlemagne’s Europe. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

The South China Morning Post called Cha “the most influential Chinese martial arts novelist of the 20th century.” BBC Chinese praised him for being one of the few influential figure in multiple fields, from literature to media, politics to business. After his death in 2018, after a long battle with cancer, may fans took to Weibo and cited some of Cha’s famous quotes to commemorate his work. ““Hunting the white stag in a flurry of snow. Happily penning the tale of the divine couple amidst the green feathered birds. Jin Yong was the soul of Chinese wuxia fiction. May he rest in peace,” one user commented. “Wuxia fiction was once considered less elegant. However, Jin Yong’s works are not only elegant but also popular. His works created so many ‘heroic gurus.’ However, he was the real guru!” “Life is like a fight. Then, you leave quietly.” [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Jin Yong’s Life

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: Louis Cha, was born, in 1924, in a prosperous town along the Yangtze River delta, the second of seven siblings, to a family that had a history of service to the throne. In 1727, after one ancestor offended the Emperor with a poorly chosen poetic couplet, his severed head was displayed on a pike. Two centuries later, when Japan invaded China during the Second World War, Cha’s family was displaced, and his mother, ill with exhaustion, died while fleeing Japanese bombs." After the Communist Revolution, in 1949, Cha’s father was deemed a class enemy and executed, and the family estate was seized. By then, Cha was living in the safety of Hong Kong, a British crown colony. He hoped to be a diplomat, but, with no options in the new Communist government, he worked as a screenwriter, film critic, and journalist. He began writing wuxia serials in 1955, to immediate acclaim. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018 **]

Jia Guo wrote in SupChina: “The death of his father during the Cultural Revolution may have been a big turning point in his career. As Straits Times reports: “After the communists swept into power in 1949, his father was deemed an oppressive landowner and executed. Following the news of the death, Cha ‘wept for three days and three nights in Hong Kong, and was sad for half a year, but he didn’t hate the army that killed his father,’ he wrote in Yueyun. ‘Because thousands, tens of thousands, of landowners had been killed in all of China; this was a big upheaval.’ “Consequently, because ‘he always felt the weak should not be oppressed,’ he began writing wuxia novels, he said.” [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Frisch wrote: In 2014, “I met Cha at the Shangri-La Hotel, which sits at the foot of the rain-forested mountain that dominates Hong Kong Island, for an interview about his literary legacy. Cha has been frail since suffering a stroke, in 1997; he is unable to walk or write, and speaks with difficulty, relying on a retinue: his third wife, his secretary, his publisher, a nurse, a personal assistant, and a rotating cast of protégés. The meeting, one aide told me, would likely be the last interview of Cha’s life. We had lunch in a private dining room, and he sat facing the door, the feng shui seat of honor. His voice, thick with home-town dialect, was weak and hoary, but he managed a few answers in a mix of Mandarin, Shanghainese, and Cantonese. (His English and French have left him.) I asked him about the political meaning of his work, and he made a surprising acknowledgment. “Master Hong of the Mystic Dragon Sect?” he said, referencing the antagonist of his final novel, “The Deer and the Cauldron.” “Yes, yes — that means the Communist Party.” Cha acknowledged that several of his later novels were, indeed, allegories for events of the Cultural Revolution. **

He continued writing when he moved to Hong Kong and started his own newspaper Ming Pao Daily in 1959 (which still sells in Hong Kong today). As editor of the newspaper Cha attacked Beijing in his editorials. And at night he worked away on the daily instalments of his martial arts epics. He only stopped in 1972 after completing what some critics regard as his best novel, Tale of the Sacrificial Deer, about the personality cult of an emperor intent on ruling all of China.

Jin Yong’s Career

Jia Guo wrote in SupChina: “Cha published his first novel at age 15 in 1939, but was expelled from school two years later for distributing satirical content via newspaper. He was enrolled in the Central School of Governance in Chongqing in 1944 but was expelled again after voicing disapproval over the behavior of some of the school’s Kuomintang members. “Cha later graduated from Soochow University in Shanghai. He began his life as a journalist at Takungpao in Shanghai." Cha got his start as a paid novelist when he was asked to fill in for the serial writer at a newspaper in Shanghai. In 1948,” one year before the Communist takeover of China and the creation of the PRC in 1949, Cha was assigned to Hong Kong. “The success of “Condors,” his third novel, allowed him to found his own newspaper, Ming Pao Daily News, in 1959 and served as its first editor-in-chief. The paper now has four North American branches, in Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco, and New York. [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

As editor of the newspaper Cha attacked Beijing in his editorials during the day worked on the daily installments of his martial arts epics at night. He stopped in 1972 after completing what some critics regard as his best novel, "Tale of the Sacrificial Deer". Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: In the paper’s early years, Cha wrote many of its front-page stories and editorials himself, decrying Maoist excesses during the Great Leap Forward famine and the Cultural Revolution. At first, Ming Pao hovered near bankruptcy, but it was kept afloat by its must-read fiction supplement, which serialized other people’s novels as well as Cha’s own, in genres ranging from dime-store noir to Lovecraftian horror. Cha staffed the newsroom of Ming Pao with classically trained historians and poets, mostly refugees from mainland China, and this gave his newspaper, along with his novels, a classical texture that Communist cultural reforms starched out of much post-revolutionary literature (including most contemporary Chinese books translated into English today). Cha’s stridently anti-Maoist editorials earned him credible death threats from Hong Kong’s Communist underground, and, in 1967, he briefly left Hong Kong for the safety of Singapore. When he returned, his reputation as a political journalist who risked his life for the cause of his fatherland had grown.

Jia Guo wrote in SupChina: In addition to his achievements in novel writing, Cha was involved in current affairs through Ming Pao. In 1964, he voiced opposition against China’s decision to build nuclear weapons amid the nation’s poverty and starvation. Cha also took a firm stance against the Cultural Revolution. Often facing threats and attacks from radical left-wing Hong Kong activists, Cha received special protection from the British Hong Kong government until the 1970s. Cha was also an advocate of democracy and freedom. He quit the drafting committee of Hong Kong’s Basic Law in 1989 in support of the student protesters. Due to Cha’s stance against the Chinese government, his novels and publications were banned in mainland China from the 1950s to the 1970s. [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Jin Yong’s Writing

Jia Guo wrote in SupChina: “Cha’s works are largely set in the world of the jianghu, a society of martial arts advocates who travel across China to teach martial arts skills while upholding a strict code of honor. In addition, unlike traditional martial arts novels, where characters are secondary to plot, Cha’s works are character-driven, with plots determined by character arcs. As a result, even though the novels depict a surreal world, the characters seem real and down to earth. Many Chinese grew up either reading Cha’s novels or watching TV series inspired by them. [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: With his combination of erudition, sentiment, propulsive plotting, and vivid prose, he is widely regarded as the genre’s finest writer. “Of course, there were other wuxia writers, and there was kung-fu fiction before Jin Yong,” the publisher and novelist Chan Koonchung said. “Just as there was folk music before Bob Dylan.” [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

Many of Cha’s plot points hinge on such conflicts, tucked between flashier punch-’em-up scenes. Later in “Condors,” when the adopted son of a nomadic-tribe aristocrat learns that he is ethnically Han Chinese, readers reared on stories of millennia-old conflicts between the Chinese and nomads from the north will register the tension between filial piety and patriotism. But the scenario may bewilder those approaching wuxia for the first time. (Readers wishing for a visual aid, and who have thirty-odd hours to spare, can consult an English-subtitled television adaptation of “Condors,” from 2003.)

For traditionalists, who admire Cha’s slightly antique Chinese style — classically inflected, densely kinetic — it is hard to imagine a satisfactory English register that would preserve both its richness and its narrative speed. Proper names, which read smoothly in snappy Chinese syllables but become cumbersome in English, must sometimes be diluted, sacrificing strict fidelity to keep the text breathing. (Without these adjustments, a kung-fu maneuver like luo ying shen jian zhang, a fleeting five syllables in Chinese, becomes the clunkier “Wilting Blossom Sacred Sword Fist.”)

Jin Yong's Books

“Jin Yong ‘s 15 best-selling novels were written between 1955 and 1972 and have been translated and published in English. Cha has said that that Western readers may find his novels hard to appreciate, as the adventures are intricately interwoven with Chinese idioms, folklore and culture. Many regard "Tale of the Sacrificial Deer", about the personality cult of an emperor intent on ruling all of China, finished in 1972, as his best work. [Source: South China Morning Post, March 3, 2017]

“Xiao Ao Jiang Hu“, published in 1967 and variously translated as “The Smiling, Proud Wanderer“ and “State of Divinity“, is based on a story about friendship and love, deception and betrayal, ambition and lust for power. In the story, various parties are vying to recover a scroll that contains a powerful martial arts technique that can propel the owner to premiere leadership, but are eventually outdone by a young lad, Little Fox, who is devoid of all ambitions. The story deals with Little Fox's journey: his development as a swordsman and his witnessing the various intrigues which take place. Many warlords and fighters from six clans lust after the manuscript, among them the leader of a so-called Five Mountains Alliance.

Despite the popularity of Jin Yong's novel, the symbolism of the six clans has never been coherently interpreted. The Five Mountains Clan might be taken to be an indirect reference to the five sacred mountains in China. The various clans have also been interpreted as a parody of one people with multiple political systems. Jin wrote, in a 1983 epilogue to his book, that the rival clans in his book personify “political prototypes “he observed in China during the Cultural Revolution, without being specific allegories to any particular persons or groups. He asserted, “Only what is rooted in our common humility can withstand the test of time and have lasting value.”

Jin's “Xiao Ao Jiang Hu “was originally serialized in his newspaper, the Ming Pao Daily of Hong Kong, as well as in 21 other newspapers in various languages. Its leading characters have sometimes surfaced in political dialogues around the world, with one politician accusing another of acting like Master Yue (hypocritically) or Master Zho (harboring secret ambitions to become dictator). The book has been adapted into three major movies (“The Swordsman,” 1991; “The Swordsman II,” 1992; and “The East is Red,” 1993) and a 40-episode TV series (“Laughing in the Wind”)]

“Laughing in the Wind“ is a story about friendship and love, deception and betrayal, ambition and lust for power which was originally titled “Xiao Ao Jiang Hu“ when it was published in 1967, and has been variously translated as “The Smiling, Proud Wanderer“ and “State of Divinity“ . The title “Laughing in the Wind“ refers to a piece of music jointly created in friendship by two elderly swordsmen of opposing clans, which eventually leads to their tragic deaths.

Sum Lok-kei wrote in the South China Morning Post: “The Deer and the Cauldron” was Cha’s last and most satirical novel. It was adapted seven times as a television drama and was the base of four films — including two starring Hong Kong’s best known comedian Stephen Chow Sing-chi as Wei. “Smiling, Proud Wanderer” was in the 1960s as China was going through a brutal period known as the Cultural Revolution, the book tells the story of different sects fighting for a mystical martial arts manual, which led readers to ponder whether Cha was referring to events happening in mainland China. In the afterword, Cha denied the plot was based on real world events. [Source: Sum Lok-kei, South China Morning Post, November 1, 2018]

Legends of the Condor Heroes and the Condor Trilogy

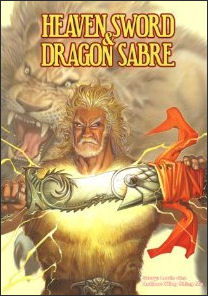

Jin Yong is best know for the "The Condor Trilogy", which includes "The Legend of the Condor Heroes" (1957), "The Return of the Condor Heroes" (1959), and "The Heaven Sword and the Dragon Saber" (1961). The "Legend of the Condor Heroes" begins in the year 1205, just before the Mongol conquest of China, and the trilogy ends more than a 150 years later, after approximately 2.86 million Chinese characters — the equivalent of one and a half million English words.

Huang Tingting wrote in the Global Times: "Legends of the Condor Heroes" focuses on the adventures of heroic grassroots couple Guo Jing and Huang Rong (Lotus Huang in the English version). It is set during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), a time when the weakened Song empire was under constant threat from the northern Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) and, later on, invasions from the Mongols. From Jin aristocrats to Mongol rulers and Song swordsmen, the novel makes use of hundreds of characters to create an epic world of martial arts and entangled human stories, not just about familial bonds and romance, but also brotherhood and patriotism. "Jin Yong flips the metaphorical significance of north and south, the northern government is the object of criticism, while it is the anti-establishment southerners who become the righteous patriots who will save the empire," translator Anna Holmwood. told the Global Times. [Source: Huang Tingting, Global Times, November 9, 2017]

Sum Lok-kei wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Legends of the Condor Heroes” “marks the start of the “Condor trilogy”, following protagonist Guo Jing on his journey to learn his twisted family history and train with mystical kung fu masters. Guo, a man of Han ethnicity who was born in Mongolia, also faces a dilemma in picking a side in a looming conflict between the two forces. This novel was also the first of Cha’s books to be visualised. Despite being an ongoing serial at the time, it was turned into a film titled Story of the Vulture Conqueror by Emei Film Company in 1958. The book went on to be adapted into five more films and 10 TV drama series, including a 1994 series featuring actress Athena Chu Yan as Guo’s lover, Huang Rong. [Source: Sum Lok-kei, South China Morning Post, November 1, 2018]

“The Return of the Condor Heroes” is said to be Cha’s most romantic work, the second entry in the “Condor trilogy” tells the bittersweet story of young man Yang Guo and “Little Dragon Maiden” — his martial arts teacher-turned-lover. In this tale the ill-fated couple battle through fatal obstacles seeking reunion. In five films and eight drama series, the pair was portrayed by famous actors and actresses, including a memorable TV iteration in 1983 that featured Andy Lau Tak-wah as Guo and Chan Yuk-lin as the “Little Dragon Maiden”.

English Translations of The Condor Trilogy

The Condor Trilogy is currently being translated in English to a 12 volume set. The English version of “Legends of the Condor Heroes” is divided into four books. “Hero Born”, the first volume translated by British-Swedish translator Anna Holmwood and priced at around US$20, was published by the UK's Maclehose (Quercus) Press in February, 2018. It is the first time a trade publisher has attempted a translation of the trilogy. Translator Gigi Chang is working on the second volume and Maclehose is planning to bring on another translator to the project. An American edition was under negotiation in 2018. [Source:Huang Tingting, Global Times, November 9, 2017]

Huang Tingting wrote in the Global Times: “A five-year effort, the book is the first in the press house's twelve-volume translation project that includes two other masterworks from Jin Yong - Shendiao Xialü (lit. The Condor Couple) and Yitian Tulongji (lit. Heaven Sword and Dragon Slaying Saber). A week ago, news about the English edition sparked discussion on Chinese social media platforms, where netizens expressed their concern and curiosity about how Holmwood would deal with the culturally specific martial arts terms in the novel that don't have equivalent counterparts in English - many are concepts borrowed from traditional Chinese culture. "Everything has been thought about, every word on every page balanced and considered," wrote Holmwood about the book, but refused to go into detail about her translation due to the fact that she is still finalizing the book.

“The difficulty in translating the book is easy to imagine as there have been only a few English-language adaptations of the story - the latest being a 1998 comic of the same name by Hong Kong illustrator Lee Chiching. Referencing Jin Yong's other work is also problematic as only three of Jin Yong's 15 works have been translated into English. "I greatly respect the translators who worked on these books, but I made a conscious choice not to read their translations before embarking on my work," Holmwood told the Global Times when asked if she had gone through those English editions for reference. "I wanted to find my own way of dealing with the complexity of recreating the richness of Jin Yong's writing in another language and context," she wrote.

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: But Cha’s books have resisted translation into Western languages. Chinese literature, which traditionally prizes poetry over fiction, derives much of its emotional force from oblique allusions, drawing on a deep well of shared cultural texts, and Cha’s work is no exception. (Over three times the length of Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” series.) Holmwood’s translation offers the best opportunity yet for English-language readers to encounter one of the world’s most beloved writers — one whose influence and intentions remain incompletely understood. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

It’s a credit to Holmwood that, in her translation, the novel’s thicket of historical names, florid kung-fu moves, and branching narratives do not obscure Cha’s storytelling verve. The book began as a meandering newspaper serial, and its form is digressive, but, after a few dozen pages, the blizzard of names and ancient dates becomes less daunting, and the reader can begin rooting for individual characters, fretting over their choices and their trials. But Holmwood’s deft maneuvering between translation and transliteration keeps Cha’s signature pacing mostly intact. And her version maintains enough allusive breadth to pique the interest of the sort of fan who might learn Elvish to dive deeper into Tolkien’s universe, without sacrificing the original’s page-turning appeal.

Jin Yong’ Characters

Sum Lok-kei wrote in the South China Morning Post: Some of the best-known Jin Yong characters include: 1) Zhang Wuji from The Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre: The last protagonist to complete the “Condor trilogy” is Zhang Wuji who becomes a cult leader and goes up against the Yuan dynasty. Unlike Guo and Yang, Zhang is more of a pacifist and less prone to killing his opponents. During his TV career, award-winning actor Tony Leung Chiu-wai played Zhang in a 1986 series aired on TVB. [Source: Sum Lok-kei, South China Morning Post, November 1, 2018]

2) Wei Xiaobao from The Deer and the Cauldron is a breakout from the writer’s previous protagonists. Instead of a young man aspiring to become a kung fu master, Wei is a cunning and witty boy born to a sex worker in the Qing dynasty. In the book, Wei goes on to fake his identity as a eunuch, befriend young emperor Kangxi and have seven wives. 3) Linghu Chong is featured in “The Smiling, Proud Wanderer”. In the afterword to this novel, Cha outlined his ideal hero in protagonist Linghu Chong, a hermit who longs for freedom and detachment from “Jianghu” — the real world that is vested with power struggles and politics. Award-winning actor Chow Yun-fat portrayed Linghu in a 1984 TV adaptation of the book.

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: “Guo Jing, the hero of “Condors,” is a simpleton with a hero’s destiny, who perseveres through hard work and basic decency. As a child, he is protected by Genghis Khan, spending his boyhood honing martial-arts skills on the Mongolian grasslands, mentored by a tight circle of kung-fu adepts. A roving Taoist monk finds him practicing his moves on the steppe and offers him secret meditation lessons, atop a cliff, to improve his technique — on the condition that he not tell his other masters. This is a classic premise in Chinese literature: dueling loyalties, to one’s elders and one’s own ambitions, compounded by a clashing reverence for different teachers. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

Impact of Jin Yong’s Work

Sum Lok-kei wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Since the 1950s, generations of Hong Kong people have grown up with film and television adaptations of Jin Yong’s works, attaching the names of his characters to actors and actresses who would go on to become cultural icons. [Source: Sum Lok-kei, South China Morning Post, November 1, 2018]

“Jin Yong novels are now largely known through their many TV, film, comic-book, and video-game adaptations. But the original books retain a powerful hold on China’s popular imagination. At one point, Jack Ma, the chairman of Alibaba, turned Jin Yong into a corporate ethos, asking each of his employees to choose one of Cha’s characters as an avatar reflecting his or her personality, and to follow the “Six Vein Spirit Sword,” a wuxia-styled company credo: put the customer first, rely on teamwork, embrace change, and so on. Cha has more female fans than any other wuxia writer, perhaps, in part, because the books have an emotional complexity that is rare in the genre. “There are some remarkable love stories in Jin Yong,” Regina Ip, a senior Hong Kong politician and Cha superfan, told me. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: Former Chinese Wall Street Journal editor-in chief Yuan Li said that generations of Chinese have been inspired by the work of Jin Yong: Yuan Li said on Twitter; “We all read and reread his novels in our teens, twenties, thirties, until today. His novels took us to a magical place where justice always prevails. “But for people who read him in the 1980s and 1990s, Jin Yong meant a lot more because we had limited access to the outside world. He opened our eyes.” [Source: Jia Guo, SupChina, October 30, 2018]

Television Version of Xiao Ao Jiang Hu

According to The Week: “To understand Cha’s enduring power, look no further than Hunan Satellite TV’s latest hit series New Xiao Ao Jiang Hu. The series, which stars Wallace Hou and Chen Qiaoen from Taiwan and Chinese starlet Yuan Shanshan in the lead roles, was a hit even though the story had already been adapted for the small screen six times (the book’s English title is The Legendary Swordsman). [Source: Week in China, March 22, 2013]

“Why is it so popular? Ling Huchong, hero of Xiao Ao Jiang Hu, is an orphan who stumbles on a coveted kung-fu manuscript ‘Star-Sucking Skills’ (its adherents learn to absorb the powers of their opponents). With his new-found skills, Ling helps his father-in-law Ren Woxing take down the ruthless “Invincible East” to become the leader of a martial arts sect.

“Xiao Ao Jiang Hu was hugely influential when it was first published in 1967 and the book has been described as Cha’s most controversial work because of its political connotations. In fact, critics say they are surprised that it has been adapted for Chinese television today (previous adaptations were produced in Hong Kong and Taiwan). Critics say Cha’s caricature of “Invincible East” as an effeminate but deranged kung-fu master is a parody of Mao’s self-styled title as the “red sun in the east” (although in the latest TV version, the allusion may have been muted by casting a woman — Chen Qiaoen — as Invisible East). The book’s character is so hungry for power he even goes to the extreme of castrating himself in order to master the skills outlined in another legendary sword manuscript, ‘The Sunflower Manual’.

“Meanwhile the father-in-law character was given a name that means “I do as I will,” calling to mind Mao’s notorious self-characterisation as wu fa wu tian, which means “defying law and nature”. Cha, who has always been critical of the Communist Party, has acknowledged that Xiao Ao Jiang Hu was a reflection of the Cultural Revolution. “I attacked worship of the individual,” he noted, hinting that the characters in the plot could be seen as politicians rather than kung-fu chieftains.

“While most of Cha’s novels are set in rich historical contexts, stretching back through the Tang Dynasty to the Ming and Song eras, Xiao Ao Jiang Hu is an exception. Cha says he intentionally left out the historical backdrop: “The ruthless struggle for power is the basic condition of political life, from antiquity to the present, in China and abroad… Characters of all these types have existed under every dynasty, and most likely in other countries as well,” he writes in the afterword to Xiao Ao Jiang Hu.

Jin Yong and Politics

Both Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek disliked Jin Yong. His novels were banned in China until 1984, and 1989 in Taiwan. The two leaders suspected that his works contained hidden political meaning. According to The Week; “Critics say Cha’s kung-fu novels strike a chord with a wide audience. While entertaining to read, he uses tales of kung-fu as a literary device to address serious issues like the misuse of power and the causes of corruption (hence why Chiang Kai-shek wasn’t a fan too). In Cha’s fictional world there is social justice, even if it is usually achieved less through the forces of law and order and more by the arrival of his fearless heroes. “As such, his tales also draw on the Chinese concept of the ‘mandate of heaven’, an ethos that sees a cruel and corrupt regime eventually brought down by a strong warrior. Cha’s heroes are akin to vigilantes, filling a void left by an absence of rule of law. “Kung-fu novels must depict justice and righteousness. Good people fight off bad guys. Traditional ethics are asserted through the characters and their stories, not by preaching with words,”Cha told the China Daily. [Source: Week in China, March 22, 2013]

Nick Frisch wrote in The New Yorker: “In 1981, Cha’s prominence in Hong Kong earned him an invitation to Beijing, to meet Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s pragmatist successor. Deng treated Cha’s family to a private dinner and professed himself an avid fan. Cha returned the compliment, telling reporters that Deng had a noble bearing, “like a heroic character in one of my books; I admire his fenggu,” the wind in his bones. Then, as the 1997 termination of Britain’s colonial lease of Hong Kong approached, Cha was appointed to a prestigious political committee charged with implementing Beijing’s vague promises of political “autonomy,” the price extracted by London in exchange for a peaceful handover. Hong Kong, a city full of refugees from the regime, watched nervously as Cha staked out conservative positions on democratic representation. Supporters of his anti-Communist editorializing felt betrayed, finding his new positions too accommodating to Beijing; others wondered if his desire to participate in the politics of his fatherland, and his newfound coziness with the Communist Party, had an ulterior, authorial motive: to be read. Deng, by lifting the Communist Party’s censorship ban on “decadent” and “feudal” wuxia novels, uncorked a reading craze. The timing was good: after Mao’s vandalisms, many Chinese sought to xungen, or return to their roots. Cha’s novels offered narrative pleasures steeped in the splendors of China’s past. [Source: Nick Frisch, The New Yorker, April 13, 2018]

“For decades, Cha brushed aside claims that his fiction allegorized modern politics. For many readers, this stretched credulity: as Ming Pao was documenting the horrors of the Mao period in its news and opinion pieces, Cha’s daily wuxia installments featured an androgynous kung-fu master whose followers worship with cultish devotion. Another novel’s antagonist was a sinister sect leader who, with his shrill and domineering wife, seeks to establish supremacy over the jianghu. The parallels to Chairman Mao and his wife, Jiang Qing, and their Red Guard followers, were not hard to see. Yet, Cha has always been coy about whether his books were meant to yingshe, or “shoot from the shadows,” to indirectly critique current politics through a narrative of the past.

““Condors,” written in the late fifties, captures the trauma of the Communist takeover, through the ancestral memory of the nomad invasions from the north. Its characters face the same challenges as Cha’s generation: deciding whether to join the new northern regime or flee to the south as a patriotic refugee, and the anguish of losing the rivers and mountains of one’s ancestral land. Though it’s a work of kung-fu fiction, the book evokes the central Chinese metaphor of writing history: the mirror, an edifice of the past that we gaze at, seeking glimmers of the present.

Martial Arts Novelist Liang Yusheng

Liang Yusheng is another acclaimed martial arts novelist. Liang got started writing martial arts, or wuxia , fiction in the 1950s, and continued writing until the mid-80s. In 1984 he moved to Australia and largely vanished from the public eye, unlike his contemporary Louis Cha (aka Jin Yong). Liang passed away in Sydney on January 2009 at the age of was 85. [Source: Danwei.org, January 27, 2009]

Liang's most famous works are “Romance of the White-Haired Maiden“ , loosely adapted by Ronny Yu into the 1993 film “The Bride With the White Hair“, and “Seven Swordsmen of Mount Heaven“, most recently adapted by Tsui Hark into the 2005 film “Seven Swords“.

According to The Beijing News: “Liang Yusheng was born Chen Wentong on March 22, 1924, to an educated family in Mengshan, Guangxi. After the anti-Japanese war was won, Liang went to Guangzhou's Lingnan University to study international economics. After graduating he became editor of the supplement to Hong Kong's Ta Kung Pao newspaper. In 1954, a dispute in the martial arts world between the White Crane style and [Wu style] Tai-chi escalated from a war of words in the newspaper to an actual fight between the heads of the two schools. Lo Fu, who was general editor of the New Evening Post at the time, serialized Liang's “The Dragon Fights the Tiger“ to capitalize on martial arts fever. This novel is seen as the beginning of “new wuxia.” Over the three decades beginning in 1954, when he started writing “new wuxia novels,” through 1984, when he declared that he was “putting away his sword,” Liang wrote 35 novels in 160 volumes, totaling 10 million characters.”

In an interview with Lo Fu published a few years ago in Southern Metropolis Daily, journalist Li Huaiyu provides some details about newspaper politics at the time Liang started writing: “The New Evening Post's big news headline on that day was “Two fighters face off at 4 o'clock before 5,000 Hong Kong spectators.” Having a flash of inspiration, Lo Fu persuaded Liang Yusheng to write a wuxia novel. The day after the fight, New Evening Post ran a notice that it would serialize wuxia fiction to satisfy readers' desire for fighting. The following day, “The Dragon Fights the Tiger“ , the product of “one day of planning “on Liang's part, began publication. Later, Lo invited Louis Cha to “join the fight,” and thus “The Book and the Sword shook the world“.”

Lo said, “There was the new Commercial Daily, you see, and they saw the readers the New Evening Post was getting by running Liang's wuxia fiction, so they asked if he could write for them. We had to agree to that, because we had to support the Commercial Daily, you know. We had launched it as a leftist paper to take over from Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po, which had been involved in a lawsuit with the Hong Kong government that accused Ta Kung Pao, Wen Wei Po, and New Evening Post of instigating social unrest. The three papers could potentially have been shut down, so we immediately began plans for another paper, the Commercial Daily. But when we had it about ready, the lawsuit ended with the other papers not getting shut down. So the Commercial Daily carried on, but we decided to turn it into a more neutral paper to attract more readers. The content would be more plebian and not so leftist. Since wuxia attracted readers, we naturally let Liang write for them. But we had to have it too, so we immediately found Louis Cha, who was quite happy to do it.”

Books: A list of Liang Yusheng's novels is available on Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liang_Yusheng

Image Sources: Amazon, University of Washington, Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021