BATTLE OF RED CLIFFS

Chibi, Red Cliff battle site The Battle of Red Cliff is one of the key episodes of “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.” It is a real historical event, otherwise known as the Battle of Chibi, that took place on the Yangtze river in the winter of A.D. 208-209 during the end of Han dynasty, 12 years before the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period. Cao Cao's navy is moored on one bank of the Yangtze while Liu Bei and his ally Sun Quan are plotting on the other. Cao Cao is ultimately defeated and forced to flee back to Jingzhou. Liu Bei and Sun Quan’s victory thwarts Cao Cao's effort to conquer the land south of the Yangtze River and reunite the territory of the Eastern Han dynasty. Liu Bei and Sun Quan in turn take control of the Yangtze, which provides them with a line of defence and the basis for the later creation of the two southern states of Shu Han and Eastern Wu. The battle has been called the largest naval battle in history in terms of numbers involved.

The de facto leader of the Wei kingdom, Cao Cao was the most powerful leader in the Battle at Red Cliff and was one of the most powerful men in China at that time. He commanded an 800,000-strong army and wanted to expand his kingdom to the south and west. Sun Quan is the King of the southern state Wu. Liu Bei is the leader of a western state. Zhiu Yu, the viceroy of Wu and Zhuge Liang, a military advisor for Liu Bei, form a friendship and convince the leader of Wu and Shu to form an alliance to battle Cao Cao and ultimately prevail with a force of only 50,000 men. There are a number if warriors such as Zhoa Yun, Zhang Fei and Guan Yu that play key parts in the battle. At first it takes some time to become familiar with all the characters and their relationships to one another — particularly for Western audiences who are not familiar with the story.

The Battle of Red Cliff determined the borders of the Three Kingdoms period, when China had three separate rulers. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ From the initial marshaling of forces on both sides, to the final decisive pitched battle, the whole sequence of events lasted mere several months, but has since then inspired people's imagination for over a thousand years, and even well into today. Poets, painters, calligraphers, playwrights, novelists, and many others, all in their various creative ways, join to extol this historical and historic romance of the legendary battle, as well as its constellation of heroes and heroines... On the whole, the battle set the stage for the ultimate partitioning of the then nominal existence of a weak Empire into three independent kingdoms, Wei, Shu, and Wu. Yet the subsequent and culminating reunification of the whole China once again as an empire, was not effected by any of the three original aspiring camps. History does have a life of its own.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) factsanddetails.com; THREE KINGDOMS (A.D. 220-280), SIX DYNASTIES (A.D. 220 -589) AND JIN DYNASTY (A.D. 265 – 420) factsanddetails.com; ROMANCE OF THE THREE KINGDOMS factsanddetails.com; SUI DYNASTY (A.D. 581-618) AND FIVE DYNASTIES (907–960): PERIODS BEFORE AND AFTER THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 690-907) factsanddetails.com CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; FOLKLORE, OLD STORIES AND ANCIENT MYTHS FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL STORYTELLING, DIALECTS AND ETHNIC LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; OLD BOOKS OF IMPERIAL CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; MING DYNASTY LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JOURNEY TO THE WEST factsanddetails.com ; JING PIN MEI, CHINA’S MOST FAMOUS EROTIC NOVEL factsanddetails.com ; DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER factsanddetails.com ROMANCE OF THE THREE KINGDOMS factsanddetails.com ; SEX AND LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; YUAN DYNASTY CULTURE, THEATER AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA AND THEATER factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HISTORY OF THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PEKING OPERA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 2, The Six Dynasties, 220–589" by Albert E. Dien and Keith N. Knapp Amazon.com "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms" by Luo Guanzhong and Martin Palmer Amazon.com; "Three Kingdoms" (Chinese Classics, 4 Volumes) by Luo Guanzhong and Moss Roberts Amazon.com; Film "Red Cliff" (English Subtitled), Starring: Tony Leung Chiu Wai , Takeshi Kaneshiro , Fengyi Zhang, Directed by: John Woo Amazon.com

Background to the Battle of the Red Cliffs

Cao Cao

In 208 A.D., in the final days of the Han Dynasty, shrewd Prime Minster Cao Cao convinced the fickle Emperor Han the only way to unite all of China was to declare war on the kingdoms of Xu in the west and East Wu in the south. Thus began a military campaign of unprecedented scale, led by the Prime Minister, himself. Left with no other hope for survival, the kingdoms of Xu and East Wu formed an unlikely alliance. Numerous battles of strength and wit ensued, both on land and on water, eventually culminating in the battle of Red Cliff. During the battle, two thousand ships were burned.” [Source: IMDb]

According to foreignercn.com: “Cao Cao, who declared himself the Prime Minister, led his troops to attack southern China after uniting the north. At Xinye, he was defeated twice by Liu Bei’s forces but Liu Bei lost Xinye and had to move to Jingzhou. Unfortunately, Liu Biao had died by then and left Jingzhou split between his two sons Liu Qi and Liu Cong. Liu Bei led the civilians of Xinye to Xiangyang, where Liu Cong ruled but Liu Bei was denied entry. Liu Cong later surrendered to Cao Cao, and Liu Bei had no choice but to move to Jiangxia where Liu Qi ruled. On the way, Liu Bei and the civilians were pursued by Cao Cao’s troops and several innocent civilians were killed. Liu Bei and his men managed to reach Jiangxia where he established a strong foothold against Cao Cao’s invasion. [Source: foreignercn.com]

“To resist Cao Cao’s invasion, Liu Bei sent Zhuge Liang to persuade Sun Quan in Jiangdong to form an alliance. Zhuge Liang managed to persuade Sun Quan to form an alliance with Liu Bei against Cao Cao and stayed in Jiangdong as a temporary advisor. Sun Quan placed Zhou Yu in command of the forces of Jiangdong (East Wu) to defend against Cao Cao’s invasion. Zhou Yu felt that the talented Zhuge Liang would become a future threat to East Wu and tried several times to kill Zhuge, but failed. In the end, he had no choice but to co-operate with Zhuge Liang for the time being as Cao Cao’s armies were at the border.”

According to IMDb, based on the film “Red Cliff”: In the summer of AD 208 “Cao Cao embarks on a campaign to eliminate the southern warlords Sun Quan and Liu Bei in the name of eliminating rebels, with the reluctant approval of the Emperor. Cao Cao's mighty army swiftly conquers the southern province of Jingzhou and the Battle of Changban is ignited when Cao Cao's cavalry unit starts attacking the civilians who are on an exodus led by Liu Bei. During the battle, Liu Bei's followers, including his sworn brothers Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, give an excellent display of their legendary combat skills by managing to hold off the enemy while buying time for the civilians to retreat. The warrior Zhao Yun fights bravely to rescue his lord Liu Bei's entrapped family but only succeeded in rescuing Liu's infant son. Following the battle, Liu Bei's chief advisor Zhuge Liang sets forth on a diplomatic mission to Eastern Wu to form an alliance between Liu Bei and Sun Quan to deal with Cao Cao's invasion. Sun Quan was initially in the midst of a dilemma of whether to surrender or resist, but his decision to resist Cao Cao hardens after Zhuge Liang's clever persuasion and a subsequent tiger hunt with his Grand Viceroy Zhou Yu and his sister Sun Shangxiang. Meanwhile, naval commanders Cai Mao and Zhang Yun from Jingzhou pledge allegiance to Cao Cao and were received warmly by Cao, who placed them in command of his navy. [Source: IMDb, D-Man2010 based on the historical record Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms rather than the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms]

Ingenuity and Intrigue and the Battle of Red Cliffs

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Battle of Red Cliff is a prime example of how ingenious tactics can result in a brilliant victory out of an outnumbered situation. The intrigue games plotted by all three camps involved to outwit one another prior to the battle, the dramatic twists and turns during the course of battle, as well as the impacts and developments after the battle, are so fascinating as to have triggered much discussion and study among posterity.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Frances Wood told the BBC: "It's very much just about warfare but also cunning strategy. There are wily generals who do very clever things. If they run out of arrows, they send a boat down the river past the enemy camp, and the enemy thinks, 'Goodness me what is this?' and they fire a million arrows into the side of the boat. And they capture them in straw, and so that's how you get spare arrows. "So it's full of stories that are not just about slaying or taking territory, but also about being clever, and outwitting your enemy." [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 15, 2012]

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: “It is deception not force of numbers that wins the battle of Red Cliff. But there is more scheming to come from Liu Bei and friends. "Knowing that the enemy has a spy in their camp, they publicly beat and humiliate one of the most important generals so that this is reported back and his defection then looks completely authentic," explains Kaiser Kuo. Consequently, when Cao Cao's army sees the defector's ship heading toward them, they do not do anything about it. They are expecting him. "In fact his ship is laden with flammable materials and he sets it on fire and manages to set a good part of the enemy fleet afire. They say that the Red Cliffs, the cliffs that give their name to both the famous battle and the John Woo movie are still charred black to this day because of smoke from the burning fleet."

Tapestry of Characters in the Battle of Red Cliffs

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Contributing no less to the Red Cliff legend's everlasting popularity are the players and stakeholders starring in this remarkable performance. Hardly can any other times throughout Chinese history rival this brief period in such a sublime showing of a galaxy of talents. Across all three camps, there was no shortage of a gifted persona: intelligent strategists as well as valiant warriors emerging and rising all at the same time. Facilitated by human's habitual choosing of sides, reinforced or incited further by fictionalized rendering in the popular novels and dramas, generations of enthusiastic fans cheer their favorite figures of their choice while perusing this part of history. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Liu Bei

“It was an age of confrontation and rivalry among heroes. They were all best of the best. Their vivid persona and dynamic talents marked an era full of great tension, momentum, and drama. Before and after the Battle of Red Cliff, and into the times of the Three Kingdoms, the leaders of Wei, Shu, and Wu did all they could to entice the best over to their camps from all possible sources, to the extent that Cao Cao once made three consecutive "Talent Scout" announcements explicitly looking for talents regardless of the candidates' character. It was a controversial move; however, the motivation was really no different from Liu Bei's paying three persistent visits to Zhuge, both indicative of an urgent "thirst" for talents. \=/

“The roll call reveals a list of unforgettable names: Liu Bei, Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, Zhuge Kongming, and Zhao Yun from Shu; Sun Quan, Zhou Yu, Lu Su, and Lu Xun from Wu; Cao Cao and his sons, Xun You, Jia Xu, and Sima Yi from Wei. These larger-than-life historical figures, either in their dashing, heroic acts, or poetic mood of utterances, each with his unique talents exemplified classical paragons for us to admire. Is it the Times itself helping perpetuate the Heroes, or the Heroes themselves helping glorify the Times? In Three Kingdoms we might divine some inspirations.” \=/

The main characters in the film “The Battle of Red Cliffs” are: Zhou Yu (Tony Leung), Zhuge Liang, Cao Cao, Sun Quan (Chang Chen), Sun Shangxiang, Zhao Yun, Gan Xing, Xiao Qiao, Liu Bei, Lu Su (Hou Yong), Sun Shucai, Li Ji, Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, Huang Gai.

Synopsis of the Film Red Cliff

According to IMDb: In Autumn of A.D. 208, “100,000 peasants fled with their beloved leader Liu Bei from Cao Cao's million man army. With the aid of heroes like Zhao Yun and Zhang Fei, they escape across the Great River (Chinese 'Yangtze') to take refuge with Sun Quan, the leader of the south. As Cao Cao prepares his huge navy to invade southern China and destroy them both, geniuses like Zhuge Liang and Zhou Yu devise a grand strategy. They hope to destroy Cao Cao's 10,000 ships with fire upon the river, but must first trick Cao Cao into chaining his ships together, and then change the direction of China's famous and freezing North Wind. While these two struggle to put aside the rivalry between Liu Bei and Sun Quan's forces, they must hatch their legendary schemes before Cao Cao is ready. [Source: D-Man2010, IMDb, based on the historical record Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms rather than the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms |]

“After the hasty formation of the alliance, the forces of Liu Bei and Sun Quan call for a meeting to formulate a plan to counter Cao Cao's army, which is advancing slowly towards Red Cliff at godspeed from both land and water. The battle then begins with Sun Shangxiang leading a light cavalry unit to lure Cao Cao's vanguard army into the Eight Trigrams Formation laid down by the allied forces. Cao Cao's vanguard army is utterly defeated by the allies but Cao Cao shows no disappointment and proceeds to lead his main army to the riverbank directly opposite the allies' main camp where they laid camp. While the allies throw a banquet to celebrate their victory, Zhuge Liang thinks of a plan to send Sun Shangxiang to infiltrate Cao Cao's camp and serve as a spy for them. The duo maintain contact by sending messages via a pigeon. The film ends with Zhou Yu lighting his miniaturised battleships on a map based on the battle formation, signifying his plans for defeating Cao Cao's navy.|

“Sun Shangxiang has infiltrated Cao Cao's camp and she has been secretly noting details and sending them via a pigeon to Zhuge Liang. Meanwhile, Cao Cao's army is seized with a plague of typhoid fever which kills a number of his troops. Cao Cao cunningly orders the corpses to be sent to the allies' camp, hoping to pass the plague on to his enemies. The allied army's morale is affected when some unsuspecting soldiers let the plague in, and eventually a disheartened Liu Bei leaves with his forces while Zhuge Liang stays behind to assist the Eastern Wu forces. Cao Cao hears that the alliance had collapsed and is overjoyed. At the same time, his naval commanders Cai Mao and Zhang Yun propose a new tactic of interlocking the battleships together with iron beams to minimize rocking when sailing on the river and reduce the chances of the troops falling seasick. The Eastern Wu forces look on as Liu Bei leaves the alliance. |

“Subsequently, Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang make plans on how to eliminate Cao Cao's naval commanders Cai Mao and Zhang Yun, and produce 100,000 arrows respectively. They agreed that whoever fails to complete his mission will be punished by execution under military law. Zhuge Liang's ingenious strategy of borrowing of arrows with straw boats brought in over 100,000 arrows from the enemy and aroused Cao Cao's suspicions about the loyalty of Cai and Zhang towards him. On the other hand, Cao Cao sends Jiang Gan to persuade Zhou Yu to surrender, but Zhou Yu tricks Jiang Gan instead, into believing that Cai Mao and Zhang Yun are planning to assassinate their lord Cao Cao. Both Zhuge Liang and Zhou Yu's respective plans complement each other when Cao Cao is convinced, despite earlier having doubts about Jiang Gan's report, that Cai and Zhang were indeed planning to assassinate him by deliberately 'donating' arrows to the enemy. Cai and Zhang are executed and Cao Cao realised his folly afterwards but it was too late. |

“In the Eastern Wu camp, Sun Shangxiang returns from Cao Cao's camp with a map of the enemy formation. Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang decide to attack Cao Cao's navy with fire after knowing that there is a special climatic condition known only to Eastern Wu's forces, that the South-East Wind (to their advantage) would blow sometime soon. As the Eastern Wu forces made preparations for the fire attack, Huang Gai proposes to Zhou Yu the Self-Torture Ruse to increase their chances of success, but Zhou Yu does not heed it. Before the battle, the forces of Eastern Wu have a final moment together, feasting on glutinous rice balls to celebrate the Winter Festival. Meanwhile, Zhou Yu's wife Xiao Qiao heads towards Cao Cao's camp alone secretly, in hope of persuading Cao Cao to give up his ambitious plans but she fails and decides to distract him instead to buy time for the Eastern Wu forces. The battle begins when the South-East Wind starts blowing in the middle of the night and the Eastern Wu forces launch their full-scale attack on Cao Cao's navy. On the other hand, Liu Bei's forces, which had apparently left the alliance, start attacking Cao Cao's forts on land. |

“By dawn, Cao Cao's entire navy has been destroyed. The allied forces launch another offensive on Cao Cao's ground army, stationed in his forts, and succeeded in breaking through using testudo formation despite suffering heavy casualties. Although Cao Cao is besieged in his main camp, he manages to holds Zhou Yu hostage after catching him off guard together with Cao Hong. Xiahou Jun appears as well holding Xiao Qiao hostage and causes the allied forces to hesitate. In the nick of time, Zhao Yun manages to reverse the situation by rescuing Xiao Qiao with a surprise attack and put Cao Cao at the mercy of the allied forces instead. Eventually, the allied forces decide to spare Cao Cao's life and tell him never to return before leaving for home. In the final scenes, Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang are seen having a final conversation before Zhuge Liang walks away into the far distance with the newborn foal Mengmeng.” |

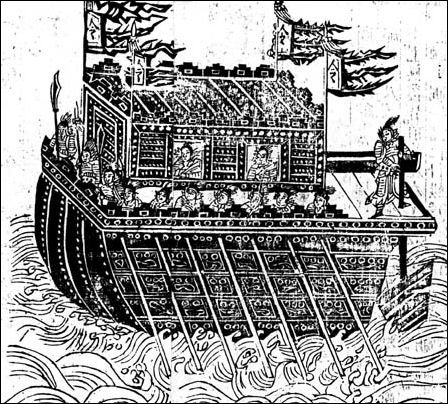

Song-era warship

History of the Three Kingdoms and Red Cliff Narrative

Director John Woo said in an interview with CCTV-6 that the film “Red Cliff” was based primarily the historical record “Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms” not the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the fifth year of Emperor Shenzong's Yuanfeng reign in the Northern Song period (1082), more than 800 years after the epic Battle of Red Cliff, the famous poet-official Su Shi (Dongpo) and friends made two trips to Red Nose Cliff (Chibiji) west of the town Huangzhou. To commemorate these trips, Su wrote two rhapsodies that would earn him universal praise in the annals of Chinese literature: "Odes to the Red Cliff." Afterwards, Red Nose Cliff at Huangzhou became known as "Dongpo's Red Cliff." [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“For Su Shi, this was also a time when he had to endure the hardships of exile from court that resulted from the Wutai Poem Incident. In his rhapsodies Su yearned nostalgically for the daring bravura of heroes who fought at Red Cliff centuries earlier, while also facing the realities of life's brevity and the hypocritical nature of people. Consequently, he was able to develop a clear and philosophical form of critical self-examination on the aspects of change and permanence. It was exactly the predicaments of his personal difficulties at this time that made it possible for Su to see through the veil of history and make the trips to his Red Cliff passed down and commemorated through the ages. For example, dramas based on stories revolving around Su Shi and Red Cliff were produced in great numbers during the following Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Countless calligraphers also repeatedly transcribed Su's two rhapsodies on Red Cliff, which likewise became popular among painters wishing to illustrate and celebrate Su Shi. \=/

“The Ming novelist Luo Guanzhong's dexterous mix of facts and fiction, coupled with his imaginative characterization of the individuals and their ingenuity, has played a key role in making the Battle of Red Cliff wonderfully impressive and remarkable. Yet he was not the first one to have told the story of the Three Kingdoms and Red Cliff. The narrative tradition started with Cheng Shou's History of the Three Kingdoms, a historian's account written in the Jin dynasty when China was reunified by the house of Sima. This in combination with oral storytelling scripts later from the Song and Yuan dynasties, formed a rich source of materials from which Luo was able to derive and create his historical novel, the ever popular masterpiece “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms”. \=/

“Printers of the Ming and Qing dynasties, cognizant of the appealing charm of the Three Kingdoms story, promoted it further with illustrated editions. Some even engaged renowned writers such as Li Zhi, Zhong Xing, Li Yu, and Mao Zonggang for annotation, boosting the social status of the novel and its reading. In the mind of the Ming and Qing literati, “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms” reigned alone in the novel category. It won such rave review and was so enthusiastically received that Li Yu and Jin Shengtan ranked it as the "Top of the Four Wonder Books", and a "Most Brilliant Writing of Talent and Taste".” \=/

Song-era warship

Su Shi and the "Former Ode to the Red Cliff”

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Su Shi (1036-1101), also known as Su Dongpo, had a long career as a government official in the Northern Song. Twice he was exiled for his sharp criticisms of imperial policy. Su is also one of the most noted poets of the Northern Song period. The following short essay describes a small boat party on the Yangzi River. The boat-trip took place at Red Cliff, traditionally thought to be the place where Cao Cao a disastrous defeat at the hands of his enemies, Liu Bei and Sun Chuan, in 208. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Su Shi, “also known as Zhizhang and Resident of Tong Po, is native of Meishan of Shichuan, and was an imperial scholar in the 2nd Year of Chia You (1057). He holds a particularly revered position in Chinese literary history, and ranks as one of the Four Song Masters in calligraphy, while being the first scholar to create the scholar painting in Chinese painting history. He is one of the most important literary masters in the Northern Song period. Su had a very unstable career as a government official, and was exiled from court that resulted from the Wutai Poem Incident to Huangzhow in the 2nd Year of Yuan Feng (1079). This marked a turning point in his life and work, and the Former and Latter Odes to the Red Cliff were representative works from this period.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

The "Former Ode to the Red Cliff" in the collection at the the National Palace Museum, Taipei was personally written by Su Shi” and is a “particularly rare masterpiece in literary and art. The Ode depicted Su and his friends travelling on a small boat to visit the Red Nose Cliff just outside Huangzhow city on July 16 in the 5th Year of Yuan Feng (1082), and recalled the Battle of Red Cliff when Sun Quan won victory over the Cao army during the times of the Three Kingdoms; through this Ode, Su expressed his views about the universe and life in general. \=/

“This Ode was written upon the invitation of his friend Fu Yao-yu (1024- 1091), and from the phrase "Shi composed this Ode last year" at the end of the scroll, one deduces that it was probably written during the 6th Year of Yuan Feng, when Su was 48 years of age. From Su's particular reminders of "living in fear of more troubles", and "by your love for me, you will hold this Ode in secrecy", one has a sense of Su's fear as a result of being implicated in the emperor's displeasure over writings. \=/

“The start of the scroll is damaged and is missing 36 characters, which were supplemented by Wen Zhengming (1470 ~ 1559) with annotations in small characters, although some scholars believe that the supplementations were actually written by Wen Peng. The entire scroll is composed in regular script, the characters broad and tightly written, the brushstrokes full and smooth, showing that Su had achieved perfect harmony between the elegant flow in the style of the Two Wang Masters that he learned from in his early years, and the more heavy simplicity in the style of Yen Zhenqing that he learned in his middle ages.” \=/

Red Cliff, Part I by Su Shi

In “Red Cliff, Part,” Su Shi wrote: In the autumn of the year "jen.hsu" (1082), on the sixteenth day of the seventh month, Itook some guests on an excursion by boat under the Red Cliff. A cool wind blew gently, without starting a ripple. I raised my cup to pledge the guests; and we chanted the Full Moon ode, and sang out the verse about the modest lady. After a while the moon came up above the hills to the east, and wandered between the Dipper and the Herdboy Star; a dewy whiteness spanned the river, merging the light on the water into the sky. We let the tiny reed drift on its course, over ten thousand acres of dissolving surface which streamed to the horizon, as though we were leaning on the void with the winds for chariot, on a journey none knew where, hovering above as though we had left the world of men behind us and risen as immortals on newly sprouted wings. [Source: “Red Cliff, Part I” by Su Shi (1036-1101), also known as Su Dongpo, “Anthology of Chinese Literature, Volume I: From Early Times to the Fourteenth Century,” edited by Cyril Birch (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 381-382 ]

“Soon when the wines we drank had made us merry, we sang this verse tapping the

gunwales:

Cinnamon oars in front, magnolia oars behind

Beat the transparent brightness, thrust upstream against flooding light.

So far, the one I yearn for,

The girl up there at the other end of the sky!

“One of the guests accompanied the song on a flute. The notes were like sobs, as though he were complaining, longing, weeping, accusing; the wavering resonance lingered, a thread of sound which did not snap off, till the dragons underwater danced in the black depths, and a widow wept in our lonely boat.

“I solemnly straightened my lapels, sat up stiffly, and asked the guest: “Why do you play like this?” The guest answered: ‘Full moon, stars few Rooks and magpies fly south. …’ “Was it not Ts’ao Ts’ao who wrote this verse? Gazing toward Hsiak’ou in the west, Wu.ch’ang in the east, mountains and river winding around him, stifling in the close green … was it not here that Ts’ao Ts’ao was hemmed in by young Chou? At the time when he smote Ching.chou and came eastwards with the current down from Chiang.ling, his vessels were prow by stern for a thousand miles, his banners hid the sky; looking down on the river winecup in hand, composing his poem with lance slung crossways, truly he was the hero of his age, but where is he now? And what are you and I compared with him? Fishermen and woodcutters on the river’s isles, with fish and shrimp and deer for mates, riding a boat as shallow as a leaf, pouring each other drinks from bottlegourds; mayflies visiting between heaven and earth, infinitesimal grains in the vast sea, mourning the passing of our instant of life, envying the long river which never ends! Let me cling to a flying immortal and roam far off, and live forever with the full moon in my arms! But knowing that this art is not easily learned, I commit the fading echoes to the sad wind.”

“Have you really understood the water and the moon?” I said. “The one streams past so swiftly yet is never gone; the other for ever waxes and wanes yet finally has never grown nor diminished. For if you look at the aspect which changes, heaven and earth cannot last for one blink; but if you look at the aspect which is changeless, the worlds within and outside you are both inexhaustible, and what reasons have you to envy anything?

“Moreover, each thing between heaven and earth has its owner, and even one hair which is not mine I can never make part of me. Only the cool wind on the river, or the full moon in the mountains, caught by the ear becomes a sound, or met by the eye changes to colour; no one forbids me to make it mine, no limit is set to the use of it; this is the inexhaustible treasury of the creator of things, and you and I can share in the joy of it.” The guest smiled, consoled. We washed the cups and poured more wine. After the nuts and savouries were finished, and the wine.cups and dishes lay scattered around, we leaned pillowed back to back in the middle of the boat, and did not notice when the sky turned white in the east.”

Ming-Era Illustrated Red Cliff Texts

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of “A Newly Proofed Edition of ‘The Romance of the Three Kingdoms’”, a Ming imprint and proofed by Zhou Yuejiao of Shulin in 1591: “This book is the version edited by the owner of the Wanjuanlo Bookshop, Zhou Yue, of the Jinling area during the Ming dynasty. The printing process was extremely careful, having particularly procured ancient editions, made corrections and annotations and cross-checked the references, as well as commissioned the famous type cutters of Nanking - Wan Xiyao and Wei Shaofeng - to cut the type. It can be said to be the highest quality edition of the bookshop. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The book consists of 250 chapters in 12 volumes, and the chapters are set out in accordance with the order adopted in Luo Kuanzhung's original work. The text was then slightly edited to seem more elegant. The preamble "History of “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms”" set out biographies of the main characters in book, so that readers would better understand their family backgrounds. \=/

“Each chapter contains an illustration, so that the total printed illustrations are 240 and are portrayed across the two pages. The illustrations identify the chapter, and on each side of the drawing is a short rhyme composed on the subject of the chapter, which are all written by literati. The function of these rhymes is rather like a theatrical show, where antithetical couplets are used as a hint to the audience. It is worth noting that the lines of the illustrations are energetic, the characters clearly outlined, with vivid and dynamic depictions of action, especially for those climatic chapters. Chapter 36 "Xia Hozun Pulls Out and Eats His Eye", for example, depicted Xia Hozun being injured by a surprise attack by Cao Xing, one of Lü Pu's generals. After he was shot in the left eye, he pulled out the eye with the arrow and called: "One must not waste any drop of blood or essence given by one's parents!" And he promptly put the eye into his mouth and ate it. Luo Kuanzhong used exaggerated, theatrical means to depict Chen Shou's two - dimensional character - the Blind Xia Ho - as a heroic three-dimensional figure, giving the space of imagination for the readers. \=/

“Chapter 54 "Guan Yunchang Kills Generals Across Five Barriers", Chapter 94 "Pan Tong Offers the Serial Trick" relating to the Battle of Red Cliff, and Chapter 98 "Zhou Kongjin Wins Battle of Red Cliff" are all vividly depicted by the skillful etching and dramatic style of the Jinling prints. It could be said to be the most popular version of the "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" in Nanking at the time.” \=/

Qing-Era Illustrated Red Cliff Text

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of “First of the Four Wonder Books: History of the Three Kingdoms”, a Qing imprint (1888): “This is the "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" critiqued by Mao Lun and Mao Zhonggang, of the Qing dynasty, and is commonly referred to as the "Mao Critique Edition". The front of the volume was entitled "Top of the Four Wonder Books", while the front page and center of the folio are both annotated "Most Brilliant Writing of Talent and Taste", showing that both titles have been adopted by bookstores in general and are used to market the books. In fact, "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" was named "Top of the Four Wonder Books" by Li Yu of the late Ming dynasty, with the other three books, "Water Margin", "Journey to the West" and "Jin Ping Mei"; Mao Zongkang named "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" as the "Most Brilliant Writing of Talent and Taste" in imitation of the late Ming literary talent Jin Shentan's critique of the six masterpieces. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Therefore the front page of the book was printed with the brand of the famous Shanghai bookstore, Saoye shanfang, during the reign of Guangxu period, and was entitled "Mao Shenshang's Critique of “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms”/ Most Brilliant Writing of Talent and Taste/ Saoye shanfang edition". At the top it was annotated "Masterpiece lost by Jin Shengtan", and at the bottom it was impressed in red seal with the words "Published and supervised by Saoye shanfang". Mao Lun, also known as Teyin and Shenshan, and Mao Zongkang, known as Xushi and Juean, both were native of Changzhou in Jiangsu. This brand shows that the Saoye shangfang of Shanghai was using the most popular Mao Critique Edition, and it was the commonly seen printed edition in bookstores at the time. \=/

“The entire book consisted of 120 chapters in 19 volumes, and at the commencement of the main volume the individual portraits of the 40 male and female characters appeared in the story, including Liu Bei, Guan Zhuangmo and Zhang Huanho, were depicted; these were followed by a single full page of the illustration of "Three Honorary Brothers in the Peach Garden", and finally the preface by the bookstore upon the reprint. This edition was in line with Li Zhuowu's practice of revising the 240 chapters into 120 chapters, but the main text had been edited by the Maos, not only to make the story more elegant and easier to read, but also added their own critiques and included poetry from the Tang, Song and Qing dynasties. The main text began with the Ming poet Yang Shen's poetic phrase: "The Yantze River rolls east" from "God by the River". All readers praised this edition as being elegant and easy to read, making it the most popular edition to this date.”\=/

Red Cliff Art

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Red Cliff became a common motif in the vocabulary of painting and calligraphy by various literati over the centuries. Literati of different eras each interpreted the historical, literary, and emotional facets of Su Shi's Red Cliff [a famous poem] in different ways.” Later “even professional artists came to incorporate the theme into their works, revealing its depth and richness over the ages. Certain ideas of the Three Kingdoms period inspired by Su Shi's rhapsodies on Red Cliff may seem remote from actual history. Nonetheless, the land remains as before, the emotions they aroused having long since changed. Yet each time they inspire new generations of painters and calligraphers to revisit Red Cliff and the Three Kingdoms through the medium of Su Shi, illustrating their own images and ideas on Red Cliff for posterity. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of“Imitating Zhao Bosu's Latter Ode on Red Cliff,” a handscroll by Wen Zhengming (1470-1559): The given name of Wen Zhenming (1470~1559) was initially "Bi", but he later went by the self-given name "Zhenming". He was the most influential painter of the Wu-style during the 16th century. This scroll is based on Su Shi's "Latter Ode on the Red Cliff", and is divided into eight sections, depicting Su Shi and his two friends returning to the Red Cliff with wine and fish. The fundamental colour of the entire scroll is light green, and although it is said to be an imitation of Zhao Boju's style, the lines and strokes visible under the paint seems transparent and more layered, appearing to be closer to the light green traditions of the literati Zhao Mengfu during the Yuan dynasty. The visitors themselves are depicted in simplistic lines, while the mountains and rocks are stacked closely and variable, demonstrating the leisurely spirit of the literati in the face of such wondrous scenery. The year annotated on the work is the 27th year of Jia Jing reign (1548), and Wen was by then 79 years of age. This is clearly one of his later works. The back of the scroll contained an annotation by Wen's son, Wen Jia (1501~1583), describing the origins of this painting. \=/

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of "The Red Cliff Mountains" from “Illustrated Travels among Mountains”, a Ming imprint during the Chongzhen reign (1628-44): The Red Cliff Mountains This is an illustration from the "Illustrated Travels among Mountains", in the style of ancient records. The top of the volume was annotated by Mohui Printhouse of Hanzhou in 6th Year of Chongzhen (1633), stating "Red Cliffs and Fucha was painted by Lan Tiensun and Sun Zizhen". Lan and Sun are both landscape artists of the Ming dynasty. In the illustration the rapids flow between steep cliffs that seem to be implanted in the waters like a giant nose; two small fishing vessels hover by the stone cliffs. This illustration adopts stronger and thicker strokes that are not as delicate as the "Compilations". \=/

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of "The Sovereign and His Ministers: a Happy and Compatible Company" from “Illustrated Sayings on the Mirror of Ruling”, an illustrated manuscript by Shen Zhenlin with additional text by Pan Zuyin, Ouyang Baoji, Yang Sisun, and Xu Pengshou, Qing dynasty (1628-1644): Written by the Ming dynasty imperial scholar Zhang Juzhen, this book is a compilation of examples of moralistic and conscientious acts by emperors of past, as well as examples to the contrary, which were prepared for study by the Emperor Shenzong of the Ming dynasty. This chapter entitled "The Sovereign and his Ministers: a Happy and Compatible Company" refers to the story of Liu Bei visiting Zhuge Liang's straw cottage three times in order to win Zhuge's cooperation, and Zhuge reciprocates by giving "Suggestions in Longzhong". Liu Bei treated ZhuGe Liang as a most honoured guest, which attracted the disapproval of Liu's two sworn brothers, Guan Yu and Zhang Fei. Liu Bei advised Chang and Guan not to persecuted with Zhuge. Zhuge ultimately gave his life in thanks for Liu Bei's trust.” \=/

Chibitu (Red Cliff) Handscroll

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of Chibitu (Red Cliff), a handscroll by Wu Yuanzhi (fl. 1190-1196), Jin dynasty: “Wu Yuanzhi was a notable scholar during the Ming Chang Period of the emperor Jin Zhang (1190~1195), and was an expert in landscapes painting. This painting depicted Su Shi and his friends travelling the Red Cliff, and Su is shown wearing a head scarf, "passing through this enormous universe on a tiny leaf" with two visitors and a boatman. The red cliff across the river towered over them, and the pine branches on the shore bowed slightly; the delicately painted waves spread gently, seeming to represent that "the waters were calm in the gentle breeze" that evening. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Although the trees and rocks in the foreground are painted in the Lee Kuo style popular in the north, the main mountains were composed in simple short and vertically turned strokes, and the entire scroll is shaded in light ink, without the usual dramatic heavy ink and atmosphere of the Lee Kuo style. The entire work was painted on paper, and the plain, elegant spirit reflected the literary paintings made popular by Su Shi and other literati during the late North Song Period. This showed that paintings of the Jin period are merging the traditions of the north with the newly popular literary painting trend. \=/

“This scroll was originally not annotated by the author, and the end of the scroll was annotated by the famous scholar Zhao Pingwen in the 5th Year of Zhenda during the Jin dynasty. The collector Xiang Yuanbian of Ming dynasty believed the scroll to be painted by Zhu Rui of the Song dynasty, but based on more recent studies of Zhao Pingwen's work, this scroll is now attributed to the painter Wu Yuanzhi of Jin dynasty.” \=/

Red Cliff Crafts

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of “Screen depicting the Red Cliff’, an incised red lacquer screen (height: 63.6 centimeters, width: 16.5 centimeters, length: 59.9 centimeters) from the Qing dynasty, QianLung reign (1736-95): Red carving in lacquerware is created by using delicate carving work to etch out patterns of varying depths on thick lacquered boards painted in multiple layers, and through variations in the carving angle, the differences in reflections of the light created vivid variations in the subject depicted. This is the most amazing aspect of carved red lacquerware.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The instant carved fan on the Red Cliff is carved upon a board 46.3 centimeters wide and 40.3 centimeters tall. Clouds in the sky, tall pines and the steep cliffs towered over the upper left corner of the fan, while the right of the screen is filled with the wide surface of the river. The mountain ranges stretched into the distance, and a few reeds are spread over the foreground. The small boat drifted slowly, and one can seemingly hear the happy voices of Dongpo and his guests, the rowing of the paddles, and the sounds of young servants boiling tea. The powerful imagery takes us to this relaxing scene. \=/

“The other side of the fan depicts cloudy dragons rising out of the water, with three dragons fighting for a ball amongst the water vapours. Dragon patterns of this kind are highly popular during the reign of Qinglong, and represent the nobility of the emperor. It being carved on the other side of a fan on the subject of "Red Cliff" perhaps symbolized the powerful emperor's secret longing for the more relaxed life of Su Dungpo and his guests on the river! \=/

Description by National Palace Museum, Taipei of “Seal depicting the Red Cliff” (bas relief on ShouShan Blood Stone. seal: 4.2 x4.3 centimeters, height: 9 centimeters), Qing dynasty (1644-1911): Making of seals by the literati first began in the late Yuan dynasty, and gradually became popular during the Ming dynasty with many different schools. It later gained status as one of the four arts of the literati, with the others being poetry, calligraphy and painting. Chicken-blood stone from Changhua in Zhejiang Province and tian-huang stone from Shoushan in Fujian Province are both excellent stones preferred by chop makers from the Ming and Qing dynasties. The former attracted the viewer with its bright coloring, while the latter had more gentle and warm nature. In order to increase the aesthetic beauty of the seal, the maker often carved a little embossment or skilfully carved the entire chop, to make appreciation of the seal more interesting. \=/

The natural color of this particular chicken-blood stone is carved into spectacular clouds and cliffs, and the out-stretched pines over the wide river as well as the small boat told the annotated story: "The moon rises over the eastern mountain and hovers amongst the stars. The white dews covered the river, and the light and water are connected to the sky. One marvels at the enormity of the universe. Ke Zhai." This brought out the "Red Cliff" theme in the carving, and the running script appears to be taken from the "Ode on the Red Cliff" written by Zhao Mengfu. The entire stone is skilfully carved, and can be considered an outstanding work from the early Qing dynasty.

Red Cliff: The Film

In 2008, John Woo's epic film “Red Cliff” shattered Chinese box office records that had previously been held by “Titanic.” Woo began working on the Mandarin-language film in the mid 2000s. It is a coproduction between the state-owned China Film Group and Woo's Los Angeles-based Lion Rock Productions. Woo had hoped to film scenes from the movie along the Yangtze River, but was denied permission for the Chinese government.

“Red Cliff” was the most expensive movie ever made in China up to that time. It cost $80 million to make and stars Hong Kong actor Tony Leung and Japanese actor Takeshi Kaneshiro. Woo reportedly spent $10 million of his own money in the film, and spent two years writing and researching the script. He told CCTV-6 that the film primarily uses the historical record “Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms” as a blueprint for story rather than the historical novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms.” Traditionally vilified characters such as Cao Cao and Zhou Yu are given a more historically accurate treatment in the film. [Source: IMDb]

Red Cliff set the box office record for a domestic movie in China. It earned $44 million in its first week. At that time only Titanic had earned more, taking in $53 million. The film took in $250 million worldwide and was crowned Asia's box office champion at the Asian Film Awards.

In some places the film was released in two parts with the first part covering an epic ground battle and the second part focusing on a naval battle. Woo told the Daily Yomiuri, “I loved the story since I was about 10 or 12, I started with comic book...I so admired the heros like Liu Bei, Zhao Yun, Guan Yu, Zhuge Liang."

Red Cliff was the first feature film by John Woo filmed in Asia after he moved his filmmaking operation to Hollywood. Woo told the Daily Yomiuri, “When I go back to Asia, I have to relinquish what I've done in the United States. So I have to start over again and I have to go back and learn the language, the thoughts, culture and everything.”

According to IMBd: “Yun-Fat Chow was originally selected for the role of Zhou Yu, and had even earlier been considered for the role of Liu Bei. However, he pulled out just as shooting began. Chow explained that he received a revised script a week earlier and was not given sufficient time to prepare, but producer Terence Chang disputed this, saying that he could not work with Chow because the film's Hollywood insurer opposed 73 clauses in Chow's contract.”

Image Sources: Nolls website, Palace Museum Tapei, CNTO, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021