PEKING OPERA

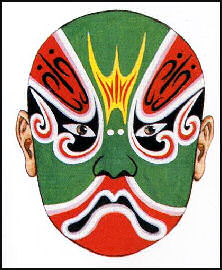

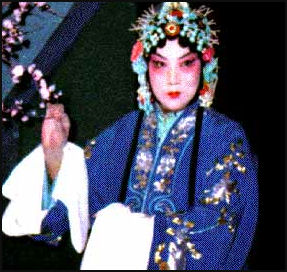

Peking Opera make up Peking Opera is a traditional form of entertainment in China that was quite popular in the old days and still has a following today. Most stories come from Chinese history and legends. Peking Opera is sometimes described as a dance drama genre. Actors often wear masks or make up to highlight their facial features. It is said the focus of the art form is spectacle and athleticism and, like Japanese kabuki, for a time all the actors, even those playing female roles, were male but since the early 20th century there have been female actors.

In Peking Opera (Beijing Opera), traditional Chinese string and percussion instruments provide a strong rhythmic accompaniment to the acting. The acting is based on allusion: gestures, footwork, and other body movements express such actions as riding a horse, rowing a boat, or opening a door. Spoken dialogue is divided into recitative and Beijing colloquial speech, the former employed by serious characters and the latter by young females and clowns. Character roles are strictly defined. The traditional repertoire of Beijing Opera includes more than 1,000 works, mostly taken from historical novels about political and military struggles. [Source: Library of Congress]

Peking Opera is an especially demanding form, both to perform and to witness. It takes a very long time to study, at least 8 to 10 years just to get in the door as a performer. To appreciate Peking Opera requires some background knowledge. “The more you know about Beijing opera, the more you love it,” said Liu Hua, a former performer and now a teacher. “The problem is that it takes a lot to know it, and fewer and fewer people have the time or the inclination.” [Source: Richard Bernstein, the International Herald Tribune, August 29, 2010]

The love of opera is very deep among some. In one of the opening scenes of the film “Farewell My Concubine”, one the character's exclaims, "If you belong to the human race, you go to the opera. If you don't go to the opera, you're not a human being." The Peking Opera that tourist groups witness today in many respects is the same — albeit shortened and abbreviated —as opera viewed by Chinese 200 years ago during the Qing dynasty. For many Chinese over the age of 70, Peking Opera was the only form of entertainment they were exposed to when they were growing up. Old men can often be seen in parks singing their favorite parts of Peking Opera.

Pallavi Aiyar wrote in the Asia Times,”Requiring years of training not only to perform but also to appreciate, Peking Opera is not an easily accessible art. Involving the mastery of a range of subtle facial expressions, enhanced by heavy layers of mask-like make up, the atonal clanging of gongs and cymbals and a series of elongated trills sung in falsettos." Journalist Henry Chu wrote in the Los Angeles Times; "What turns off many Westerners and younger Chinese from Peking Opera delights its older fans: the high-pitched, almost whiny singing; the cacophony of cymbals and clappers; the heavily stylized movements; and the bountiful symbolism, by which the slightest gesture on the nearly naked stage conveys meaning and action.”

See Separate Article MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA-THEATER AND ITS HISTORY factsanddetails.com; TYPES OF CHINESE THEATER AND REGIONAL OPERA factsanddetails.com; VILLAGE DRAMA IN THE 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA STORIES, PLAYS AND CHARACTERS factsanddetails.com; PEKING OPERA ACTORS factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA AND EFFORTS TO KEEP IT ALIVE factsanddetails.com ; REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMUNIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MODERN AND WESTERN THEATER IN CHINAfactsanddetails.com TRADITIONAL CHINESE MUSIC AND MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; FOLKLORE, OLD STORIES AND ANCIENT MYTHS FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL STORYTELLING, DIALECTS AND ETHNIC LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinese Opera Wikipedia article on Chinese Opera Wikipedia ; Beijing Opera Masks PaulNoll.com ; Literature: Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) mclc.osu.edu; Classics: Chinese Text Project ; Side by Side Translations zhongwen.com; Classic Novels: Journey to the West site vbtutor.net ; English Translation PDF File chine-informations.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Peking Opera” by Chengbei Xu Amazon.com; “Peking Opera Painted Faces” by Menglin Zhao Amazon.com “Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture” by Alexandra B Bonds Amazon.com; “Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day” by Colin Mackerras Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera: Stories and Images” by Peter Lovrick and Siu Wang-Ngai Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera: The Actor’s Craft” by Siu Wang-Ngai and Peter Lovrick Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera Makeup and Costumes (1644 - 1911): Office of Great Peace Album of Opera Faces” by Jim Brisebois and Manon Bertrand Amazon.com; “Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870-1937" by Joshua Goldstein Amazon.com; “Listening to Theater: The Aural Dimension of Beijing Opera” by Elizabeth Wichmann Amazon.com; “The Peony Pavilion: Mudan ting” by Xianzu Tang , Cyril Birch, et al. Amazon.com; “Chinese Theater in the Days of Kublai Khan” by J. I. Crump Amazon.com

Properly Defining Peking Opera and Its Recognition by UNESCO

Addressing some misconceptions about Peking Opera and more accurately describing what it is, David Rolston of the University of Michigan writes: “Peking opera should be glossed as Jingju. A lot of folk, especially in China, hope that like kabuki this genre will become known by its romanized name (over time it has had lots of Chinese names, but Jingju has been dominant in the PRC for a long time and is getting there in Taiwan). "Dance drama" will give the impression that only dance is used to tell stories in the genre. Indigenous Chinese theater (xiqu) is sometimes translated as "music drama" or "music theater"; perhaps that is the source of "dance drama."

Dance became particularly important in new plays in the 20th century starring Mei Lanfang, and Mei's main advisor, Qi Rushan said that in Chinese theater "there is no movement that is not danced" but that is an exaggerration. Masks are used, especially for deities; they are just outnumbered by face patterns (lianpu). The main purpose of the latter is to symbolically externalize elements of the personality and history of the characters who have them painted on their faces; the patterns for one particular character can be modified to fit the facial features of particular actors, but their purpose is not to highlight those features. Plays that feature singing and/or dialogue have long constituted an extremely important part of the repertoire; those plays can be entirely lacking in "spectacle and athleticism." Female actors were banned from performing onstage with male actors from the middle of the Qing dynasty to the end of that dynasty, and unevenly in major cities after that for a couple of decades. Females could all along perform for private performances and in the different foreign concessions under different regimes at different times. Female performers such as Liu Xikui outdrew the "king of Peking opera" Tan Xinpei when she moved from Tianjin to Beijing at the end of the Qing dynasty."

Peking opera was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2010. According to UNESCO: Peking opera is a performance art incorporating singing, reciting, acting, martial arts. Although widely practised throughout China, its performance centres on Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai. Peking opera is sung and recited using primarily Beijing dialect, and its librettos are composed according to a strict set of rules that prize form and rhyme. They tell stories of history, politics, society and daily life and aspire to inform as they entertain. ''Performance is characterized by a formulaic and symbolic style with actors and actresses following established choreography for movements of hands, eyes, torsos, and feet. Traditionally, stage settings and props are kept to a minimum. Costumes are flamboyant and the exaggerated facial make-up uses concise symbols, colours and patterns to portray characters’ personalities and social identities. Peking opera is transmitted largely through master-student training with trainees learning basic skills through oral instruction, observation and imitation. It is regarded as an expression of the aesthetic ideal of opera in traditional Chinese society and remains a widely recognized element of the country's cultural heritage. [Source: UNESCO]

Creation of Peking Opera the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

Peking opera was formally created in 1790 through the merging of several regional styles in China — namely two southern forms known collectively as pihuang — that have their roots in the 13th century. It incorporated regional forms of dance, mime, music and acrobatics and was more melodramatic. and even vulgar compared the older, more lyrical styles that preceded it.

Peking opera was formally created in 1790 through the merging of several regional styles in China — namely two southern forms known collectively as pihuang — that have their roots in the 13th century. It incorporated regional forms of dance, mime, music and acrobatics and was more melodramatic. and even vulgar compared the older, more lyrical styles that preceded it.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China was again ruled by foreigners, this time by the Manchus. They, however, greatly appreciated many aspects of Chinese culture and thus the Qing dynasty was, in fact, a fruitful period for the arts. The beginning of the dynasty was overshadowed by riots and revolts but a long period of peace began during the reign of the art-loving Emperor Kangxi (K’ang-hsi) (who ruled 1662–1722). [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The popularity of the sophisticated southern kunqu or kun opera was already declining. It was still admired by the educated elite, but its southern dialect and complicated lyrics made it difficult to be appreciated in North China. There, audiences preferred their own regional styles with familiar dialects, stories and melodies. Many regional opera styles from different parts of the country gained popularity in Peking at the beginning of the new dynasty. **

The opera-loving Emperor Qianlong (Ch’ien-lung) (who ruled 1736–1795) invited troupes from the province of Anhui to the capital to perform their local style, the bangzi opera or the clapper opera, which has already been discussed above. They performed at the Emperor’s eightieth-birthday celebrations, but their performances proved so successful that the troupes stayed on, becoming increasingly popular. **

Over a period of time they began to adapt the technical characteristics of other local styles. One very important person in this process was the bangzi actor Cheng Changgeng (Ch’eng Ch’ang-keng), who, in his performances, combined elements from, among others, the kunqu and the clapper opera. After an evolution spanning decades the fusion process led to a new form of opera, called jingju (ching-chü) or “theater of the capital”. In the West it is known as the Peking Opera. **

In the beginning this new style was known only in the capital, where it gained great favour in the reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi (Tz’û-hsi) (1835–1908). In the 1860s mobile troupes of performers also started to perform Peking Opera outside the capital area. It spread around the country and thus gained its status as a “national style”. In 1919 Peking Opera was performed for the first time outside China, in Japan. Soon Peking Opera troupes were also visiting the United States and Russia, taking this art form to within reach of western audiences and theater reformers, such as Brecht, Stanislavsky, Craig etc. Peking Opera is still today the most widely studied and performed traditional form of theater in China. **

History of Peking Opera

In its early years Peking Opera was looked down upon by the scholar class but was popular among the general population. Peking Opera actors were considered the dregs of society, equal in status to prostitutes and pimps. Many actors were rumored to be homosexuals, which didn't them overcome their low social position. Laws prohibited woman from performing in Peking Opera and young boys were sold under contract and trained for the women’s roles. For a while the children of actors were once barred by government decree from taking the court civil service exams.

From the late 19th to mid 20th century, it was northern China most popular theatrical entertainment and regarded as the highest artistic expression of Chinese culture. Opera were usually performed in teahouses, private parties in restaurant-theaters, guild halls and wealthy people’s homes. Performances were often held at New Year's celebrations, weddings, and sometimes even at funerals and ancestor worshiping ceremonies. By the late 19th century Peking Opera began emphasizing heroic drama and was embraced by the royal court.

Chu wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Through enthusiastic imperial patronage and popular acclaim, the genre reached its zenith in the first half of the 20th century, when opera houses played to raucous houses of the young and old, rich and poor, powerful and humble, across the nation...Abroad, Peking Opera inspired playwrights and performers from Bertolt Brecht to Charlie Chaplin. Actors such as Mei Lanfang, arguably the biggest Peking Opera star of in modern history, enjoyed a world wide following. During his only U.S. tour in 1930, Mei's shows sold out on Broadway and earned raves in Hollywood. USC and Pomona College awarded him honorary degrees for his unrivaled skill in playing dan, or female, opera roles."

Despite being singled out during the Cultural Revolution for particularly vicious attacks Peking Opera managed to survive the Mao era. During the Cultural Revolution it was deemed feudalistic and reactionary. Afterwards it did less well bouncing back than other art forms such as Western music and modern dance, both of which have since made vigorous recoveries.

Peking Opera Plays and Stories

Opera has traditionally been important in passing on Chinese culture from one generation to another. Most stories fall into two categories: “wen” (“civilian”), based on lyrical love stories; and “wu” (“military”), based on heroic tales, and often featuring spectacular acrobatics. Most Peking Opera stories come from Chinese history, theology, cosmology and literature and legends. In a typical Peking Opera, four or five heavily-made-up singers stand under trees and act out a sad love story. There is generally some kind of moral message. Some traditional Peking Operas are over seven hours long.

The plot of “Hua Deng” ("Flower Lamp"), one of China's most famous operas, is similar to Romeo and Juliet. After the couple meets and has a few rendezvous, they come to the realization they can not marry. The women character commits suicide. After the man sings a sad song on her grave he too kills himself. Another famous Peking Opera story is about a ghost longing for his life on earth.

The plots of Peking Operas are often inspired by natural disasters, revolts and fairy tales. Popular operas include are "Havoc in Heaven" (about a clever Monkey King who foils attempts by the gods to capture him); "A Drunken Beauty" (about a Tang dynasty concubine who turns to drink when the emperor passes her for a rival); "The White Snake" (a tale of demons and the power of love); "A Fisherman's Revenge"; "The Water Margin"; “Huozhuo” (about a ghost that misses her mortal lover); and "Assassinating the Tiger General" (about a concubine who seeks revenge for the death of her emperor lover by seducing a general, and then killing him after getting drunk him and then committed suicide herself).

Peking Opera Roles and Components

Peking Opera inherited its four main role categories from kunqu and other earlier theatrical forms and yet enriched them, for example, by also adding among them martial role types with acrobatic skills. The four role categories are sheng or the male roles, dan or the female roles, jing or the “painted face” roles, and chou, the comic roles. Within these main categories there are further several subdivisions to define the type variations of the main character. **

Peking opera (jingju ) has five major components: playwriting, acting, music, design, and directing. The subcategories within each of the principal role-types, both for male and female roles, are based on “a particular gender, age, social status, level of dignity, and certain primary acting skills”. Other genres of performance art that existed at same time as jingju and influenced it were huaju (spoken theater), geju (Western-style opera ), wuju (dance opera) and ballet. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020;

There was also quite a bit of mixing and mastery of several subcategories. In a review of the book, “Staging Revolution” Xiaomei Chen wrote: Yang Cunxia , who played the lead female role of Ke Xiang in Azalea Mountain, mastered not only various subcategories of female role-types such as qingyi (young and middle-aged dignified female), huadan (young lively female), and wudan (martial female), she more significantly adapted the stage steps of the male role-type of wusheng (martial dignified male) to express Ke Xiang’s courage and bravery as a military leader.

See Separate ArticleCHINESE AND PEKING OPERA STORIES, PLAYS AND CHARACTERS factsanddetails.com

Peking Opera Theater Spaces and Staging

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Chinese opera has been performed on several kinds of stages, from simple tea houses to temporary stage structures put up in market places or country fairs, and to court theaters, to private chamber theaters, and from the beginning of the 20th century, most often in the western kind of large theater houses. There exist good examples of old stages and theater houses around China. Several small pavilion-like stages belonging to a temple or a private palace still exist, and imperial, three-storied stage structures with stage machinery can be seen in Beijing, both in the Forbidden City and at the Summer Palace. The most famous of the Qing-dynasty private tea-house theaters is at the 18th century residence of Prince Gong, in Beijing. The so-called tanghui (t’ang-hui) or performances at private parties, in spaces not designed for performances, have also been popular. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

A theater space typical of the early phase of Peking Opera was the so-called xiyuan (hsi-yüan) or “opera courtyard”. There, a square stage was surrounded by the audience on three sides. The performances could last the whole day. Later, in a type of theater called the “old style theater”, the wooden stage floor was covered with a thick woollen carpet to make the acrobatic scenes safer for the performers. At the rear of the stage hung an embroidered curtain, which was the private property of the leading actor of the day. Seeing the curtain, audiences knew who was going to play the lead. **

During the heyday of Peking Opera, at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century, the opera activities were centred on the Qianmen Gate Tower area, in the old commercial centre of Peking. There were some ten theater houses and hundreds of important Peking Opera artists lived and practised their art there. From the 1950s onward Chinese opera has increasingly been staged in huge theater houses and cultural palaces constructed during the Communist regime. This has affected Chinese opera in many ways. Some performance practices have been altered, curtains are used between acts or even scenes, and modern lighting technologies are employed. The most disastrous effect created by the huge performance spaces, completely alien to the intimate scale of Chinese operas, is the use of microphones and amplifiers. It not only destroys original sounds and the balance of the operas, but also restricts some of the dance-like movements of the actors. **

The Great Theater of China in Shanghai, located near People's Square in downtown Shanghai, which was known as one of the "Top Four Stages" of Peking Opera. Built in 1930 as a prime venue for Peking Opera performance, it hosted famous artists such as Mei Lanfang, Ma Lianliang and Meng Xiaodong. The auditorium maintains its original three-tier design. Upon entering the lobby, visitors are greeted by a marble floor inscribed with sunflower and tri-star patterns. In the auditorium, the roof lighting design resembles the shape of a 32-petal lotus in full blossom. [Source: Zhang Kun, China Daily, May 26, 2018]

Peking Opera staging evolved from: 1) the traditional spare, decorative stage designs and generic stage properties; to 2) the rise of nonconventional scenery in the second half of the nineteenth century in Shanghai playhouses; to 3) the mid-twentieth century “machine-operated” stage design; to 4) Mei Lanfang’s use of flats with painted scenery in his modern-dress plays; to 5) the 1950s’ new proscenium theatres in which modern jingju were staged. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book:“Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan (Hong Kong University Press, 2018)]

Peking Opera Actors

Famous actor Zhang Jun

Peking Opera actors are as much dancers and acrobats as they are actors. They do not deliver lines like Western actors but act them out in every sense of the word using exaggerated movements and facial expressions and even elaborate physical stunts. Realism has never been a concern. More importance is often given to the actions of the actors than their roles. Many actors have traditionally come from families that have produced actors for five or six generations. The Los Angeles Times describe on young actor who came from a family of actors that was forced to carry the tradition by his mother who named him “Jirong,” which means “to continue.”

Few props are used in a Peking Opera. All the attention is focused on the actors, who play roles that everyone familiar with Peking Opera recognizes. The role types (hangdang) usually fall into one of four categories: 1) “sheng” (male roles such as scholars, soldiers and officials); 2) “dan” (female roles such as mothers, maids and female warriors); 3) “jing” (painted face characters such as demons, adventurers and heroes); and 4) “fujing” (clowns).

Male roles are divided into four categories: 1) “laosheng” (old men with beards); 2) “xiaosheng” (young men); 3) “wensheng” (scholars and bureaucrats); and 4) “wusheng” (fighters, who often do the acrobatic roles). The five most important female roles are: 1) “laodan” (respected elderly mothers or aunts); 2) “qinyi” (aristocratic ladies, in elaborate costumes); 3) “huadan” (female servants, in bright costumes); 4) “daomdan” (female warriors); and 5) “caidan” (female comedians).

See Separate Article PEKING OPERA ACTORS factsanddetails.com

Peking Opera Make-up and Costumes

Chinese actors decorate their face with paints made from oil and egg white. Some traditional Chinese actors have a cross-eyed face painted on their face with a mouth that lines up with the actor's eyes The face talks when the actor opens and closes his eyes. According to legend the tradition of face painting dates back to the 6th century B.C. when a famous warrior prince decided to paint his face to hide what he thought were his effeminate features. Among warriors face painting is supposed to imbue its wearer with strength and even magical powers.

In Peking Opera, clowns wear white patches of make-up around their eyes and nose. Warriors known as qing often have elaborate designs on their faces with symbolic value. Good guys generally had simple designs while the bad guys had more complex ones. Mask are only worn for animals such as a tiger, wolf or pig.

Costumes — such as ceremonial robes with dragon designs associated with high officials and ornament-covered padded armor associated with military heros — are deigned to highlight an actors movements. Actors playing noblemen were a silk robe embroidered with phoenix, lotus and Buddhist knot designs. Later the costumes began to reflect contemporary fashions.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: According to these “face maps”, all recorded in special pictorial manuals, the audience immediately gets information about the inner qualities of the characters portrayed. A red face, for example, indicates loyalty and uprightness, a black face a forthcoming character, a blue face pride and bravery while a white face indicates cunning and treachery. The most surprising of these types of make-up are those in which all the traces of the anatomy of the human face are faded away by a completely abstract facial painting reminiscent of a colourful tornado or of some kind of cosmic explosion. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Both the old man and old woman types wear barely any make-up, only some lines around the eyes and the mouth. The young woman role types paint their faces first with matte white. Then deep red is added around the eyes, the nose and on the sides of the face. The deep red is graded with the white of the cheeks and the nose. This pinkish make-up, shaded with deep red and highlighted with white, indicates beauty and the glow of youth. The make-up of the youthful male character is also approximately similar. **

The most spectacular types of make-up belong, as the name “pained face” already indicates, to the jing characters. In China the types of facial make-up have a history of at least over a thousand years. The early types of make-up were simple; the face was painted red, black etc. Over the centuries the make-up became more complex and reached its culmination in the hundreds of intriguing make-up designs of the Peking Opera’s jing characters. **

Peking Opera Symbols

Old man with white beard

The exaggerated facial expressions, gestures and simple props are often symbolic. A whip with tassels, for example, indicates that the actor is riding a horse. A gray beard shows someone in their 50s or 60s; a white beard shows someone in their 70s or 80; a red beard shows someone with a cruel, demented or fiery temperament and is often worn by ghosts. A beard divided into three parts indicates a man of integrity. Short mustaches indicates a person that is rough and crude. A long curled mustaches is found on characters that are sly and devious.

Lifting a foot means entering a house, pointing to the temple means bashfulness and walking in a circle means a long journey has been taken. Chairs and tables are often put together to represent things like mountains or beds. Even acrobatic moves have symbolic value. A sudden backward “vat-turn’somersault, for example, expresses the despair a person feels upon losing a loved one.

On some costumes specific animals denote military rank and specific birds denoted civil service rank Colors symbolize character and personality traits. Black indicates honesty. Blue symbolizes courage. Red indicates loyalty. White can be a tip off for a traitor. Green is associated with virtue. Black sometimes indicates vulgarity. Yellow is reserved for the emperor and the royal court.

Peking Opera Music and Dance

According to UNESCO: The music of Peking opera plays a key role in setting the pace of the show, creating a particular atmosphere, shaping the characters, and guiding the progress of the stories. 'Civilian plays' emphasize string and wind instruments such as the thin, high-pitched ''jinghu ''and the flute ''dizi, ''while 'military plays' feature percussion instruments like the ''bangu ''or ''daluo. [Source: UNESCO]

Peking Opera performances are accompanied by repetitive music and percussion often reminiscent of a galloping horse. The musicians often sit on the same stage as the actors, wearing normal street clothes. Traditional Chinese musical instruments used in Peking Opera include the “erhu” (a two-stringed fiddle with a low soft sound), “huqin” (two-stringed viola which often playing the equivalent of the melody), and “yueqin” (a four-stringed banjo-like instrument with a soft sound). Other instruments include “sheng” (reed pipes), “pipa” (four stringed lute), and assorted drums, bells and gongs. The time-keeping, galloping horse sounds come from the ban, a clapper that directs the music and provides actors with cues.

“Chinese theatrical dance,” Sophia Delta wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, “is quite varied, owing to the wide range of dramatic stories...There are dances of courage, defeat, triumph, despair, love, intrigue, sadness, satire, and madness...Form and structure [are] within the contents of the play’s plot and roles...In addition to the emotions of the moment, the character’s dominate trait becomes the subject of dance. Whether the character is heroic, regal, modest, uncouth, sly, arrogant, or evil can determine the manner in the dance os executed.”

The combat scenes are derived from the wu shu and play a part in expressing the story and plot. Delta wrote: “A hero’s sword dance is not simply a technical interlude but a display of prowess and proof of his ability to overcome an adversary. A general fleeing from his camp performs elaborate dance. all the while singing the story of his plight.” Ballet has also bee incorporated, especially in the dance and movements of the women’s roles.

Peking Opera Movement

“The choreographic nature of acting on the Chinese stage,” A.C. Scott wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, “is apparent in the formalized treatment of movement and gesture, integrated with passages of song and music, in which words are treated as time-movement units. Hand gestures symbolizing emotional reactions create a continuous visible element with the tonal movement of the actors’ singing and declamation. Graceful passages of pointing with the fingers of one or both hands move through spatial sequences attended by the following glances of the performer, whose foot movements timed to the music carry forward the motifs of the dance.”

Delta wrote: “Always present...is the manner of moving used to define the specific individual being portrayed. Roles fall into genres — human beings, animals and birds, and supernatural beings...Ghost are conceived of as being stiff, devils as curvaceous; they dance grotesquely and humorously...The intrinsic quality of each animal or bird is fancifully and fully exploited — the powerful tiger, the brazen leopard, the sly fox, or the wily eagle.”

“Because classical opera uses no scenery, the actor-dancer sets the stage by incorporating the idea of physical environment onto gesture and movement...Action expands the stage when, from atop three stacked tables, the dancer does a double somersault to indicate he is running down a mountain. Many actor-dancers turn the stage into a sea with spread-eagle leaps, diving falls and spiraling turns...A general on a symbolic horse uses slipping, sliding and collapsing movements to portray efforts to advance on icy ground.”

Image Sources: Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html; Chinese Hisorical Society; Beijing government ; Henan historical Museum; Peking Opera home page; Trisha Shadwood travel blog; UNESCO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021