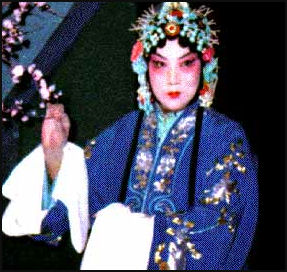

PEKING OPERA ACTORS

Famous actor Zhang Jun

Peking Opera actors are as much dancers and acrobats as they are actors. They do not deliver lines like Western actors but act them out in every sense of the word using exaggerated movements and facial expressions and even elaborate physical stunts. Realism has never been a concern. More importance is often given to the actions of the actors than their roles. Many actors have traditionally come from families that have produced actors for five or six generations. The Los Angeles Times describe on young actor who came from a family of actors that was forced to carry the tradition by his mother who named him “Jirong,” which means “to continue.”

Few props are used in a Peking Opera. All the attention is focused on the actors, who play roles that everyone familiar with Peking Opera recognizes. The role types (hangdang) usually fall into one of four categories: 1) “sheng” (male roles such as scholars, soldiers and officials); 2) “dan” (female roles such as mothers, maids and female warriors); 3) “jing” (painted face characters such as demons, adventurers and heroes); and 4) “fujing” (clowns).

Male roles are divided into four categories: 1) “laosheng” (old men with beards); 2) “xiaosheng” (young men); 3) “wensheng” (scholars and bureaucrats); and 4) “wusheng” (fighters, who often do the acrobatic roles). The five most important female roles are: 1) “laodan” (respected elderly mothers or aunts); 2) “qinyi” (aristocratic ladies, in elaborate costumes); 3) “huadan” (female servants, in bright costumes); 4) “daomdan” (female warriors); and 5) “caidan” (female comedians).

Important actors in the later part of the 20th century from Beijing, Shanghai, and Taiwan include Cheng Yanqiu (1904-1958, male actor of dan roles, Republican era, Beijing), Li Yuru (1924-2008, dan actress, pre-Cultural Revolution PRC, Shanghai), Ma Yongan (1942-2007, jing actor, Cultural Revolution model plays, Beijing), Yan Qinggu (1970-, chou actor, post-Mao, Shanghai), Kuo Hsiao-chuang (1951-, dan actress, 1970s to early 1990s, Taiwan), and Wu Hsing-kuo (1953-, sheng actor, 1980s to present, Taiwan). [Source: “Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in a Changing World” by Ruru Li, Reviewed by Siyuan Liu, University of British Columbia MCLC Resource Center Publication, September 2012)

The performance and training basics that define a jingju actor are outlined in the “Four Skills. But they weren’t always followed and there was some debate about how the male dan roles should be played. In the Qing dynasty xianggong system apprentices acted as courtesans, Cheng Yanqiu masculine personality contradicted to his feminine roles, and this complicated his relationship with his master and rival Mei Lanfang. Cheng's balance of yin and yang is best illustrated his complicated interpretation of the "water sleeve" movements in the play “Tears in the Barren Mountain” (Huangshan lei). “Cheng's masculinity is revealed through contrasting high and low notes that are slightly out of the normal range for dan singing; this singing technique allows the male actor to powerful embody the role of a heroine who suffers acutely under and oppressive taxation system”. [Source: “Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in a Changing World” by Ruru Li, Reviewed by Siyuan Liu, University of British Columbia MCLC Resource Center Publication, September 2012)]

See Separate Article MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA-THEATER AND ITS HISTORY factsanddetails.com; TYPES OF CHINESE THEATER AND REGIONAL OPERA factsanddetails.com; VILLAGE DRAMA IN THE 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA STORIES, PLAYS AND CHARACTERS factsanddetails.com; PEKING OPERA AND ITS HISTORY, MUSIC AND COSTUMES factsanddetails.com DECLINE OF CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA AND EFFORTS TO KEEP IT ALIVE factsanddetails.com ; REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMUNIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; FOLKLORE, OLD STORIES AND ANCIENT MYTHS FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL STORYTELLING, DIALECTS AND ETHNIC LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinese Opera Wikipedia article on Chinese Opera Wikipedia ; Beijing Opera Masks PaulNoll.com ; Literature: Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) mclc.osu.edu; Classics: Chinese Text Project ; Side by Side Translations zhongwen.com; Classic Novels: Journey to the West site vbtutor.net ; English Translation PDF File chine-informations.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND VIDEOS: “Chinese Opera: The Actor’s Craft” by Siu Wang-Ngai and Peter Lovrick Amazon.com; “Mei Lanfang: The Art of Beijing Opera” by Li Ling, Cao Juan Amazon.com; “Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870-1937" by Joshua Goldstein Amazon.com; “Farewell My Concubine” Directed by: Chen Kaige (DVD) Amazon.com; “Peking Opera” by Chengbei Xu Amazon.com; “Peking Opera Painted Faces” by Menglin Zhao Amazon.com “Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture” by Alexandra B Bonds Amazon.com; “Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day” by Colin Mackerras Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera: Stories and Images” by Peter Lovrick and Siu Wang-Ngai Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera Makeup and Costumes (1644 - 1911): Office of Great Peace Album of Opera Faces” by Jim Brisebois and Manon Bertrand Amazon.com; “Listening to Theater: The Aural Dimension of Beijing Opera” by Elizabeth Wichmann Amazon.com; “The Peony Pavilion: Mudan ting” by Xianzu Tang , Cyril Birch, et al. Amazon.com; “Chinese Theater in the Days of Kublai Khan” by J. I. Crump Amazon.com

Training for Peking Opera Actors

A typical performer begins training around the age of eight, nine or ten and practices for six years to master the stylized falsetto and stylized movements. Students often practice from morning to night under the tutelage of a master who has traditionally whipped or beaten boys for making mistakes.

The training for Peking Opera including doing handstands for 40 minutes while their legs are tied to a rod and staying a crouching position for more than an hour. The raining is so rigorous that some trainees develop blood in their urine. The depictions of training hardship in film “Farewell My Concubine” are very graphic. Set at the Peking Opera School, it shows children being "literally tortured into becoming performers.”

The actor Jackie Chan entered the China Drama Academy, a training school of the Peking Opera, at the age of seven. He spent over a decade enduring torturous instruction in acrobatics, gymnastics, mime, singing, dance, and martial arts under the taskmaster Ju Yu-Yim-yuen. At the school, Chan slept only five hours a night in a dormitory with 50 boys and girls. The children were given little to eat and on often beaten. Describing his first beating, "I remember dropping a piece of rice on the floor, and the teacher caned me." He added, "I was beaten almost every day. I never forgot how it felt. It made me never want to hit anyone. I don’t want children to think it's okay to beat someone up."

Chan’s parents signed a contact with the academy which essentially made him the school's indentured servant. His master took nearly all the money from his early acting roles. Chan’s kung fu training included throwing 1,000 punches in a row and then launching 500 kicks. He often did handstands on chairs and did an average of 5,000 punches and kicks a day. His singing and acting lessons were equally rigorous.

Peking Opera Actor’s Skills

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: In traditional Chinese theater the acting technique or, to be precise, “actor’s skills” are called xigong (hsi-kung). They refer to the acting tradition and methods formulated during the centuries. They are divided, for example, into the hand, the eye, the body, and the feet techniques, all of them related to physical expression, such as acting, mime, dancing, and acrobatics. Besides those skills, actors must also master very demanding singing and recitation skills. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

In addition to these main methods, the actor must have a command of several sub-techniques or “supporting techniques”. They include, for example, the skills related to the handling of certain parts of the costume, such as the long white silken extensions of the sleeves, the so-called “water sleeves” shuixiu (shui-hsiu). Though it seems very easy and natural, handling them is actually very demanding, and students practise it for years. These silken strips extend the actual movement of the actor. They can also indicate several things, such as talking sides or presenting gifts, or they can simply express powerful emotions. **

Other supporting techniques are the fan skills, related to the handling of the fan, which can be used in many ways, for example as a symbol of many things, such as a wine cup, a butterfly etc. Further skills with a beard refer to the many ways in which an artificial beard can be manipulated. Anger, thoughtfulness, hesitation and many other moods can be expressed by the handling of the beard. Further supporting skills are related, for example, to the manipulating of the hair and the handkerchief. **

In the non-naturalistic, symbolic acting style of the Chinese theater, many things can be told or illustrated by these supporting skills. A good example is the riding whip skills. Riding a horse is indicated by a riding whip the actor holds in his hand. The colour of the whip indicates the horse’s colour, and the horse’s movements, such as galloping, running for a long time, the horse’s tiredness etc., are indicated by the movements of the whip combined with the actor’s other body movements. **

Peking Opera professionals divide the acting skills into three realms. “being accurate” indicates a correct combination of the skills, while the second realm, “being beautiful”, focuses not only on the technical execution, but on the interpretation’s aesthetic values and the accuracy of the portrayal of the character. The highest of the three realms, “having a lingering charm”, is more difficult to put in words since the highest quality of artistic performance often seems to avoid exact definitions. For example, the singing of a certain star actor has been described as “being gentle as weeping and lingering as a thread”. **

Beijing Opera Training and Students

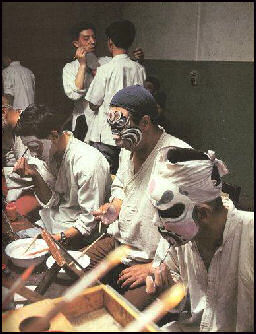

Peking Opera dressing room

Young people are still being trained Beijing Opera. They generally start their training at age 11, going to one of the several Beijing opera academies around the country aimed at producing professional performers. “Children really like it,” teacher said. “Another reason is that some parents love it, and they want their children to learn it, even if they’re not thinking about having them become professionals.” [Source: Richard Bernstein, the International Herald Tribune, August 29, 2010]

Describing the scene at a rehearsal hall at a shabby theater in the backstreets of southwest Beijing, Richard Bernstein wrote in the International Herald Tribune: “Watch out for that sword, the rehearsal director shouted. I don’t want anybody head getting cut off because you don’t know what you’re doing. Lots of weapons were on stage at the Beijing Opera Academy of China here the other day. Teenage future opera stars were armed with lances, spears, swords and daggers as they carried out an elaborately choreographed, intricate, stylized and acrobatic fight scene, all to the clash of cymbals, drums, wooden clappers and a substantial orchestra of Chinese string and woodwind instruments.

The early training lasts for six demanding, rigorous years. Given that Beijing opera is fading in popularity, especially among the younger generations, it seems strange that so many young people would want to go through it. “It such good training that the students can go in almost any direction even if they don’t end up in the opera,” Liu said. “A lot of our students end up on television or in the movies, she added. There are a lot of martial arts movies, and our students are all good at martial arts. Some of them become popular singers or actors. They’re not worried about their future.

A teacher at the Peking Opera Vocational College today told the Asian Times. “In the old days less than one out every 100 students could hope to get a place. Today we choose one out of 10.” The school currently has about 300 students who train for five years. “No one has the patience for nine-year training any more,” said Wang.

Social Status of Peking Opera Actors

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: As in many other cultures in older times, the social status of actors in China was very low, too. Whether they belonged to the private troupes of educated men, traders or officials or to the wandering troupes, the actors were regarded merely as prostitutes. Their social status is reflected in the fact that for a long time the actors were excluded from the official examinations. It was generally accepted that the actors did not choose their profession, but were forced to do so because of poverty or, for example, because the head of the family has received a criminal sentence. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

There were periods when famous actresses who were courtesans were widely admired and some high-class admirers even married them. However, these kinds of marriages were not common, because of the actor’s reputation of having low morals. Mixed companies, with both men and women, were popular in the 13th and 14th centuries, but after that they were, due the strict moral codes of Neo-Confucianism, banned. **

During the Ming dynasty the tendency was already towards companies with performers of one sex only. The later world of the Peking Opera was completely a male domain. Until the 1920’s the actors, the playwrights and the musicians were all male, and so was the audience. As all the actors were men, they also performed the female roles. Boys and men excelling at impersonating female roles were a constant headache for officials, since attractive actors were popular sex objects among the homo- or bisexual male audience. Thus, many actors were obliged to serve high-ranking admirers with their sexual favours. **

There were also, of course, personalities among actors who were admired by all levels of society purely because of their artistry and innovations. The beginning of the Peking Opera was the golden age of jing actors, who often played the roles of elderly statesmen, emperors, rebels and ministers. For decades they overshadowed the dan or the female impersonators. One of the brightest stars of the Peking Opera stage was Mei Lanfang (1894–1961). He not only brought the dan roles into focus again, but in many ways he influenced the Peking Opera’s development in the Republic of China and even during the early periods of the People’s Republic. **

Mei Lanfang, the Legendary Peking Opera Female Impersonator

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Mei Lanfang (1894-1961) is without doubt the most celebrated Peking Opera actor, both at home and abroad. He was born in Peking into a famous dan, or female impersonator, family.He began learning acting at the age of eight and made his stage debut at the age of ten. He created a sensation in Shanghai, where he worked for a longer period absorbing the new trends of the international city’s theatrical life. As in many other cultures in older times, the social status of actors in China was very low, too. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

He was a specialist of the noble female type, but was able to expand his acting to some other female types as well. He admired the old kunqu and was instrumental in its revival. However, he also created completely new dances, which are still popular today. He also created “modern” operas with stage sets, contemporaneous costuming etc. He was the head of the first Peking Opera troupe ever to perform abroad. In 1919 he performed in Japan and in 1929 in the United States. **

His performances, especially those in the Soviet Union in 1935, had far-reaching consequences, since among the full houses there were several important pioneers of modern theater, such as Konstantin Stanislavski, Bertolt Brecht, and Gordon Craig. Brecht found many elements in Mei Lanfang’s art which inspired his theories of the Epic Theater. **

During the early period of the People’s Republic Mei Lanfang was instrumental in deciding the fate of the traditional Chinese theater. As a celebrated artist and an influential, cultural and political personality he was able to persuade Chairman Mao of Peking Opera’s value as the creation of the people of China, while at the same time the Communist party was banning all art forms related to religion and the imperial past. It is very much due to Mei Lanfang that the tradition of Chinese theater continued through the middle part of the 20th century. **

Mei Baojiu — Mei Lanfang’s Son

Mei Baojiu (1934-2016) was the youngest son of Mei Lanfang and was also known for his portrayal of elegant female roles. Born in Shanghai, Mei Baojiu started training at the age of 10 with famous Peking opera artists, including Wang Youqing and Zhu Chuanming. He officially performed in public at age 13 and started performing with his father at 18. Zhuang Pinghui wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Mei was the second generation of what was known in the circle as the Mei school, started by his father, playing elegant female roles with a unique way of walking, dancing, speaking and executing perfectly timed, poised stances. Like his father, Mei made his name playing female roles in traditional Peking opera, such as consort Yu in “Farewell My Concubine”, Yang Yuhuan in “Imperial Consort Intoxicated” and Mu Guiying in “Lady General Mu Takes Command”. [Source: Zhuang Pinghui, South China Morning Post, April 26, 2016]

“His career was halted for 14 years before and during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and ’70s, when he was instead given the job of maintaining stereo equipment. Mei rarely created new shows. Most of his works were built upon his father’s. In an interview with CCTV in 2014, Mei said his mission was to continue the art in the way “I learned it, acted it, and taught it to my students” and “do practical things and try to teach as many students as I can”. He also followed in his father’s footsteps, touring the United States, Russia, Taiwan and Hong Kong in 2013 and 2014 to promote Peking opera in celebration of his father’s 120th birth anniversary.

“A member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, China’s top political advisory body, Mei Baojiu’s proposals during the annual sessions were often linked to preserving and promoting Peking opera and traditional Chinese culture. In 2014, he told China National Radio that Peking opera taught nothing but virtues and that he considered it his duty to pass it on. “It’s our mission not only to enjoy a performance but also to let the younger generation know what’s the right thing to do,” he said.

“In 2009, Mei proposed introducing Peking opera in primary schools. In 2012, he proposed creating animated works out of traditional Peking opera shows to attract young listeners. In 2016 he proposed that children should learn calligraphy, traditional Chinese characters and Peking opera so they would accept and embrace traditional Chinese culture.Mei has trained dozens of Peking opera artists, but only one was a man playing female roles.

Peking Opera Singer Li Yuru and Her Life Story

Li Yuru, (1923-2008) was one of the great Beijing Opera performers. Delia Davin wrote in The Guardian: She was born in Beijing in 1923 however, to make her seem younger, 1924 was put down on her registration papers at Beijing Theater school, and she retained this as her birth year in all her official papers. Her family, descended from Manchu nobility, had fallen into poverty. She was 10 when her mother sent her to the school. It was lonely, but she would be fed while she learned a profession. She changed her surname from Jiao to Li, her mother's maiden name, in order not to affect her family's reputation. In the past, all female roles had been played by men, and Beijing Theater school was the first co-educational training institution. Her tutors for the dan (young female) roles she studied were male performers.” She worked hard, learning plays by heart in the traditional way, and doing the arduous physical exercises that were part of the training. After six months, she was given a small role, but was booed by the audience when she failed to reach the high notes. For some years, she was given only walk-on parts. Then before a scheduled performance, both the leading student-actresses lost their voices. Still only 14, Li took the major role and received rapturous applause. From that moment on her success was assured.” [Source: Delia Davin, The Guardian, July 21, 2008]

Li Yuru, (1923-2008) was one of the great Beijing Opera performers. Delia Davin wrote in The Guardian: She was born in Beijing in 1923 however, to make her seem younger, 1924 was put down on her registration papers at Beijing Theater school, and she retained this as her birth year in all her official papers. Her family, descended from Manchu nobility, had fallen into poverty. She was 10 when her mother sent her to the school. It was lonely, but she would be fed while she learned a profession. She changed her surname from Jiao to Li, her mother's maiden name, in order not to affect her family's reputation. In the past, all female roles had been played by men, and Beijing Theater school was the first co-educational training institution. Her tutors for the dan (young female) roles she studied were male performers.” She worked hard, learning plays by heart in the traditional way, and doing the arduous physical exercises that were part of the training. After six months, she was given a small role, but was booed by the audience when she failed to reach the high notes. For some years, she was given only walk-on parts. Then before a scheduled performance, both the leading student-actresses lost their voices. Still only 14, Li took the major role and received rapturous applause. From that moment on her success was assured.” [Source: Delia Davin, The Guardian, July 21, 2008]

“When she graduated, Li organized her own troupe with some classmates and they enjoyed a successful run in Shanghai. However, the 17-year-old soon found the pressure unbearable and disbanded her troupe. She worked under the protection of various male stars and was a private disciple of Mei Lanfang and other male masters of the dan role who had responded positively to the arrival of women performers. She became a great star, particularly known for her roles in The Dragon and the Phoenix, The Courtyard of the Black Dragon, Two Phoenixes Flying Together, and Three Pretty Women. She gave birth to two daughters, Li Li in 1944 and Li Ruru in 1952.”

“When the People's Republic was founded in 1949, Beijing Opera was seen as a popular art form but in need of reform. Plays were banned for reasons such as “too much violence”, ‘sexual suggestiveness”, “reactionary politics” and even “no ideological significance”. With a relatively “clean” personal history, Li was considered suitable material for a “people's artist”. She herself was hopeful about the new regime that had brought peace and stability and, like other actors, she was delighted that they would now be respected as equal citizens. In the course of “re-education”, she made self-criticisms of her “crimes” - the bourgeois thought and individualism demonstrated in striving for fame; the make-up and fashionable clothes reflecting her bourgeois life style; and the counter-revolutionary romances and ghost plays she had performed. Although much of the repertoire disappeared, she performed plays such as The Drunken Imperial Concubine, The Xin'an Inn, The Pavilion of Red Plum Blossom, and Imperial Concubine Mei. She toured the Soviet Union and Europe several times, and gave Beijing Opera performances in Britain in 1958 and 1979.”

“All this came to an end with the cultural revolution in 1966. Li was incarcerated in an “oxpen” (a room used as an and hoc prison) and separated from her daughters who were sent to work in the countryside. When she was released in the early 1970s the theater had become a duller place; only the model works produced under the supervision of Mao's wife Jiang Qing could be staged. Curiously however, as these were all mutations of Beijing Opera, Li and her colleagues were now needed again.”

“Mao's death in 1976 brought transformations. Li could once more perform the roles she had made famous. Her favorite play was The Drunken Imperial Concubine, which she first appeared in aged 11. She performed it for the last time when she was 70. She regarded passing on her art as important and was generous in her help to younger performers. She taught many students, offering master classes and giving seminars in various theater institutions.” Her marriage, in December 1979, to Cao Yu, one of China's greatest dramatists, led her to take up writing. She published a play in 1984, while a novel that appeared in 1993 was made into a 25-episode television serial and reprinted in 2008. Her research on the performing art of Beijing Opera has recently been published in Shanghai in a collection edited by her daughter.”

Beijing Opera was a living tradition. Not only the arias, but the techniques, movements, symbolism and make-up were all passed down from one player to another. Looking back on her life, Li lamented that so many plays with their specific acting skills had been lost in the hands of her generation. What, she asked, would she say to her predecessors when she saw them in the other world? The answer should surely be that through her teaching she was also able to pass on to future generations much that would otherwise have been lost.

Image Sources: Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html; Chinese Hisorical Society; Beijing government ; Henan historical Museum; Peking Opera home page; Trisha Shadwood travel blog; UNESCO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021