MUSIC IN CHINA

Yueqin player

Impromptu traditional and regional music can be heard in local teahouses, parks and theaters. Some Buddhist and Taoist temples feature daily music-accompanied rituals. The government has sent musicologists around the country to collect pieces for the “Anthology of Chinese Folk Music”. Professional musicians work primarily through conservatories. Top music schools include the Shanghai College of Theater Arts, the Shanghai Conservatory, the Xian Conservatory, the Beijing Central Conservatory. Some retired people meet every morning in a local park to sing patriotic songs. A retired shipbuilder who leads one such group in Shanghai told the New York Times, ‘singing keeps me healthy.” Children are "taught to like music with small intervals and subtly changing pitches.”

Chinese music sounds very different from Western music in part because the Chinese scale has fewer notes. Unlike the Western scale, which has eight tones, the Chinese has only five. In addition, there is no harmony in traditional Chinese music; all the singers or instruments follow the melodic line. Traditional instruments include a two-stringed fiddle (erhu), a three-stringed flute (sanxuan), a vertical flute (dongxiao), a horizontal flute (dizi), and ceremonial gongs (daluo). [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Chinese vocal music has traditionally been sung in a thin, nonresonant voice or in falsetto and is usually solo rather than choral. All traditional Chinese music is melodic rather than harmonic. Instrumental music is played on solo instruments or in small ensembles of plucked and bowed stringed instruments, flutes, and various cymbals, gongs, and drums. Perhaps the best place to see traditional Chinese music is at a funeral. Traditional Chinese funeral bands often play through the night before an open-air bier in a courtyard full of mourners in white burlap. The music is heavy with percussion and is carried by the mournful melodies of the suona, a double-reed instrument. A typical funeral band in Shanxi Province has two suona players and and four percussionists.

“Nanguan” (16th century love ballads), narrative music, silk-and-bamboo folk music and “xiangsheng” (comic opera-like dialogues) are still performed by local ensembles, impromptu teahouse gatherings and traveling troupes.

See Separate Article MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT MUSIC IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ETHNIC MINORITY MUSIC FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MAO-ERA. CHINESE REVOLUTIONARY MUSIC factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA AND THEATER, REGIONAL OPERAS AND SHADOW PUPPET THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HISTORY OF THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PEKING OPERA factsanddetails.com ; DECLINE OF CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA AND EFFORTS TO KEEP IT ALIVE factsanddetails.com ; REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMINIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: PaulNoll.com paulnoll.com ; Library of Congress loc.gov/cgi-bin ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) List of Sources /mclc.osu.edu ; Samples of Chinese Music ingeb.org ; Music from Chinamusicfromchina.org ; Internet China Music Archives /music.ibiblio.org ; Chinese-English Music Translations cechinatrans.demon.co.uk ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com World Music: Stern's Music sternsmusic ; Guide to World Music worldmusic.net ; World Music Central worldmusiccentral.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND MUSIC: “Chinese Musical Instruments” by Yuan-Yuan Lee and Sin-Yan Shen Amazon.com “Chinese Musical Instruments” by Alan R. Thrasher Amazon.com; “Faces of Tradition in Chinese Performing Arts” by Levi S. Gibbs Amazon.com; “Music in China: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (Includes CD) by Frederick Lau Amazon.com; The Very Best Of Chinese Music by Han Ying, Various Artists, et al Amazon.com; “The Music of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Li Yongxiang Amazon.com; “Music, Cosmology, and the Politics of Harmony in Early China” by Erica Fox Brindley Amazon.com; “Chinese Music and Musical Instruments” by Qiang Xi (Author), Jiandang Niu Amazon.com; “Rocking China: Music Scenes in Beijing and Beyond” by Andrew David Field Amazon.com;

History of Music in China

Chinese music appears to date back to the dawn of Chinese civilization, and documents and artifacts provide evidence of a well-developed musical culture as early as the Zhou dynasty (1027- 221 B.C.). The Imperial Music Bureau, first established in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), was greatly expanded under the Han emperor Wu Di (140-87 B.C.) and charged with supervising court music and military music and determining what folk music would be officially recognized. In subsequent dynasties, the development of Chinese music was strongly influenced by foreign music, especially that of Central Asia.[Source: Library of Congress]

Sheila Melvin wrote in China File, “Confucius (551-479 BCE) himself saw the study of music as the crowning glory of a proper upbringing: “To educate somebody, you should start from poems, emphasize ceremonies, and finish with music.” For the philosopher Xunzi (312-230 BCE), music was “the unifying center of the world, the key to peace and harmony, and an indispensable need of human emotions.” Because of these beliefs, for millennia Chinese leaders have invested vast sums of money supporting ensembles, collecting and censoring music, learning to play it themselves, and building elaborate instruments. The 2,500-year-old rack of elaborate bronze bells, called a bianzhong, found in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng, was a symbol of power so sacred that the seams of each of its sixty-four bells were sealed with human blood. By the cosmopolitan Tang Dynasty (618-907), the imperial court boasted multiple ensembles that performed ten different kinds of music, including that of Korea, India, and other foreign lands. [Source: Sheila Melvin, China File, February 28, 2013]

“In 1601, the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci presented a clavichord to the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572-1620), sparking an interest in Western classical music that simmered for centuries and boils today. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661-1722) took harpsichord lessons from Jesuit musicians, while the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735-96) supported an ensemble of eighteen eunuchs who performed on Western instruments under the direction of two European priests—while dressed in specially-made Western-style suits, shoes, and powdered wigs. By the early 20th century, classical music was viewed as a tool of social reform and promoted by German-educated intellectuals like Cai Yuanpei (1868-1940) and Xiao Youmei (1884-1940).

“In 1601, the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci presented a clavichord to the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572-1620), sparking an interest in Western classical music that simmered for centuries and boils today. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661-1722) took harpsichord lessons from Jesuit musicians, while the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735-96) supported an ensemble of eighteen eunuchs who performed on Western instruments under the direction of two European priests—while dressed in specially-made Western-style suits, shoes, and powdered wigs. By the early 20th century, classical music was viewed as a tool of social reform and promoted by German-educated intellectuals like Cai Yuanpei (1868-1940) and Xiao Youmei (1884-1940).

“Future premier Zhou Enlai ordered the creation of an orchestra at the storied Communist base at Yan’an, in central China, for the purpose of entertaining foreign diplomats and providing music at the famed Saturday night dances attended by Party leaders. The composer He Luting and the conductor Li Delun undertook the task, recruiting young locals—most of whom had never even heard Western music—and teaching them how to play everything from piccolo to tuba. When Yan’an was abandoned, the orchestra walked north, performing both Bach and anti-landlord songs for peasants along the way. (It reached Beijing after two years, just in time to help liberate the city in 1949.)

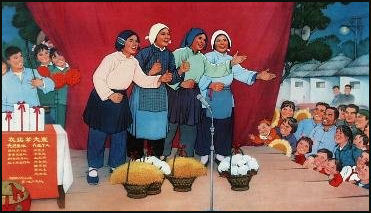

“Professional orchestras and music conservatories were founded across China in the 1950s—often with the help of Soviet advisors—and Western classical music became ever more deeply rooted. Although it was banned outright during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), as was most traditional Chinese music, Western musical instruments were used in all the “model revolutionary operas” that were promoted by Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, and performed by amateur troupes in virtually every school and work unit in China. In this way, a whole new generation was trained on Western instruments, even though they played no Western music—doubtless including many of those leaders who, in their retirement, were recruited to the Three Highs. Classical music thus made a quick comeback after the Cultural Revolution ended and is today an integral part of China’s cultural fabric, as Chinese as the pipa or erhu (both of which were foreign imports)—the qualifying adjective “Western” has been rendered superfluous. In recent years, China’s leaders have continued to promote music—and, thereby, morality and might—by channeling resources into state-of-the-art concert halls and opera houses.

Music and Society in China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”, published in 1894: “The theory of Chinese society may be compared to the theory of Chinese music. It is very ancient. It is very complex. It rests upon an essential "harmony" between heaven and earth, "Therefore when the material principal of music (that is the instruments), is clearly and rightly illustrated, the corresponding spiritual principle (that w the essence, the sounds of music) becomes perfectly manifest, and the State's affairs are successfully conducted." (See Von Aalst's “Chinese Music, passim") The scale seems to resemble that to which we are accustomed. There is a wide range of instruments. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

Confucius taught that music is an essential to good government, and was so affected by the performance in his hearing of a piece which was at that time sixteen hundred years old, that for three months he was unable to relish his food, his mind being wholly on the music.' Moreover the sheng, one of the Chinese instruments which is frequently referred to in the book of Odes, embodies principles which are “substantially the same as those of our grand organs. Indeed, according to various writers, the introduction of the sheng into Europe led to the invention of the accordion and the harmonium. Kratzenstein, an organ-builder of St. Petersburg, having become possessed of a sheng, conceived the idea of applying the principle of organstops. That the sheng is one of the most important of Chinese musical instruments is apparent. No other instrument is nearly so perfect, either for sweetness of tone or delicacy of construction."

“But we hear that ancient music has lost its hold upon the nation. “During the present dynasty, the Emperors Kangxi and Ch'ien Lung have done much to bring music back to its old splendour, but their efforts cannot be said to have been very successful. A total change has taken place in the ideas of that people which has been everywhere represented as unchangeable; they have changed, and so radically that the music art, which formerly always occupied the post of honour, is now deemed the lowest, calling a man can profess." "Serious music, which according to the classics is a necessary compliment of education, is totally abandoned. Very few Chinese are able to play on the Qin, the sheng, or the yun-lo, and still fewer are acquainted with the theory of the lies'." But though they may not be able to play, all Chinese can sing. Yes, they can “sing," that is they can emit a cascade of nasal and falsetto cackles, which do by no means serve to remind the unhappy auditor of. the traditional "harmony" in music between heaven and earth. And this is the sole outcome, in popular practice, of the theory of ancient Chinese music!

Chinese orchestra

Traditional Chinese Music

Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker: “With its far-flung provinces and myriad ethnic groups” China “possesses a store of musical traditions that rivals in intricacy the proudest products of Europe, and go back much deeper in time. Holding to core principals in the face of change, traditional Chinese music is more “classical” than anything in the West...In many of Beijing’s public spaces, you see amateurs playing native instruments, especially the dizi, or bamboo flute, and the ehru, or two-stringed fiddle. They perform mostly for their own pleasure, not for money. But its surprisingly difficult to find professional performances in strict classical style.”

In the “Li Chi” or “Book of Rites” it is written, “The music of a well-ruled state is peaceful and joyous...that of a country in confusion is full of resentment...and that of a dying country is mournful and pensive.” All three, and others too, are found in modern China.

Traditional Chinese classical music songs have titles like “Spring Flowers in the Moonlight Night on the River”. One famous traditional Chinese piece called “Ambush from Ten Sides” is about an epic battle that took place 2,000 years ago and is usually performed with the pipa as the central instrument.

The Cantonese music from the 1920s and traditional music merged with jazz from the 1930s has been described as worth listened to, but is largely unavailable on recordings because it has been labeled by the government as "unhealthy and "pornographic." After 1949 anything labeled as "feudal" (most kinds of traditional music) was banned.

Music in the dynastic periods, See Dance

Musicology of Traditional Chinese Music

As odd as it may sound Chinese music is closer tonally to European music than it is to music from India and Central Asia, the sources of many Chinese musical instruments. The 12 notes isolated by the ancient Chinese corresponds with the 12 notes picked out by the ancient Greeks. The main reason that Chinese music sounds strange to Western ears is that it lacks harmony, a key element of Western music, and it uses scales of five notes where as Western music uses eight-note scales.

In Western music an octave consists of 12 pitches. Played in succession they are called the chromatic scale and seven of these notes are chosen to form a normal scale. The 12 pitches of an octave are also found in Chinese music theory. There are also seven notes in a scale but only five are considered important. In Western music and Chinese music theory a scale structure can begin at any one of the 12 notes.

Classical music played with a “qin” (a stringed instrument similar to a Japanese koto) was a favorite of emperors and the imperial court. According to the Rough Guide of World Music, despite its importance to Chinese painters and poets, most Chinese have never heard a qin and there are only 200 or so qin players in the whole country, most of them in conservatories. Famous qin pieces include Autumn Moon in the Han Palace and Flowing Streams. In some works silence is considered as important sound.

Classical Chinese scores indicate tuning, fingering and articulations but fail to specify rhythms, resulting in a variety of different interpretations depending on the performer and the school.

Bronze Drums

Bronze drums are something that ethnic groups of China share with the ethnic groups of Southeast Asia. Symbolizing wealth, traditional, cultural bonding and power, they have been prized by numerous ethnic groups in southern China and Southeast Asia for a long time. The oldest ones—belonging to the ancient Baipu people of the mid-Yunnan area—date to 2700 B.C. in the Spring and Autumn Period. The Kingdom of Dian, established near the present city of Kunming more than 2,000 years ago, was famous for its bronze drums. Today, they continue to be used by many ethnic minorities, including the Miao, Yao, Zhuang, Dong, Buyi, Shui, Gelao and Wa. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

At present, the Chinese cultural relics protection institutions have a collection of over 1,500 bronze drums. Guangxi alone has unearthed more than 560 such drums. One bronze drum unearthed in Beiliu is the largest of its kind, with a diameter of 165 centimeters. It has been hailed as the "king of bronze drum". In addition to all these, bronze drums continue to be collected and used among the people. ~

See Bronze Drums Under LIFE AND CULTURE OF TRIBAL GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA factsanddetails.com

Nanyin: Recognized by UNESCO

Nanying was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2009. According to UNESCO: Nanyin is a musical performing art central to the culture of the people of Minnan in southern Fujian Province along China’s south-eastern coast, and to Minnan populations overseas. The slow, simple and elegant melodies are performed on distinctive instruments such as a bamboo flute called the ''dongxiao'' and a crooked-neck lute played horizontally called the ''pipa,'' as well as more common wind, string and percussion instruments. [Source: UNESCO]

Of nanyin’s three components, the first is purely instrumental, the second includes voice, and the third consists of ballads accompanied by the ensemble and sung in Quanzhou dialect, either by a sole singer who also plays clappers or by a group of four who perform in turn. The rich repertoire of songs and scores preserves ancient folk music and poems and has influenced opera, puppet theatre and other performing art traditions. Nanyin is deeply rooted in the social life of the Minnan region. It is performed during spring and autumn ceremonies to worship Meng Chang, the god of music, at weddings and funerals, and during joyful festivities in courtyards, markets and the streets. It is the sound of the motherland for Minnan people in China and throughout South-East Asia.

Xi’an Wind and Percussion Ensemble

Xi’an wind and percussion ensemble was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2009. According to UNESCO: “Xi’an wind and percussion ensemble, which has been played for more than a millennium in China’s ancient capital of Xi’an, in Shaanxi Province, is a type of music integrating drums and wind instruments, sometimes with a male chorus. The content of the verses is mostly related to local life and religious belief and the music is mainly played on religious occasions such as temple fairs or funerals. [Source: UNESCO]

The music can be divided into two categories, 'sitting music' and 'walking music', with the latter also including the singing of the chorus. Marching drum music used to be performed on the emperor’s trips, but has now become the province of farmers and is played only in open fields in the countryside. The drum music band is composed of thirty to fifty members, including peasants, teachers, retired workers, students and others.

The music has been transmitted from generation to generation through a strict master-apprentice mechanism. Scores of the music are recorded using an ancient notation system dating from the Tang and Song dynasties (seventh to thirteenth centuries). Approximately three thousand musical pieces are documented and about one hundred fifty volumes of handwritten scores are preserved and still in use.

Village Temple Musicians in China

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “Once or twice a week, a dozen amateur musicians meet under a highway overpass on the outskirts of Beijing, carting with them drums, cymbals and the collective memory of their destroyed village. They set up quickly, then play music that is almost never heard anymore, not even here, where the steady drone of cars muffles the lyrics of love and betrayal, heroic deeds and kingdoms lost. The musicians used to live in Lei Family Bridge, a village of about 300 households near the overpass. In 2009, the village was torn down to build a golf course and residents were scattered among several housing projects, some a dozen miles away. Now, the musicians meet once a week under the bridge. But the distances mean the number of participants is dwindling. Young people, especially, do not have the time. “I want to keep this going,” said Lei Peng, 27, who inherited leadership of the group from his grandfather. “When we play our music, I think of my grandfather. When we play, he lives.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, February 1, 2014]

“That is the problem facing the musicians in Lei Family Bridge. The village lies on what used to be a great pilgrimage route from Beijing north to Mount Yaji and west to Mount Miaofeng, holy mountains that dominated religious life in the capital. Each year, temples on those mountains would have great feast days spread over two weeks. The faithful from Beijing would walk to the mountains, stopping at Lei Family Bridge for food, drink and entertainment.

“Groups like Mr. Lei’s, known as pilgrimage societies, performed free for the pilgrims. Their music is based on stories about court and religious life from roughly 800 years ago and features a call-and-response style, with Mr. Lei singing key plotlines of the story and the other performers, decked out in colorful costumes, chanting back. The music is found in other villages, too, but each one has its own repertoire and local variations that musicologists have only begun to examine.

“When the Communists took over in 1949, these pilgrimages were mostly banned, but were revived starting in the 1980s when the leadership relaxed control over society. The temples, mostly destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, were rebuilt. The performers, however, are declining in numbers and increasingly old. The universal allures of modern life — computers, movies, television — have siphoned young people away from traditional pursuits. But the physical fabric of the performers’ lives has also been destroyed.

Efforts to Keep Chinese Village Temple Music Alive

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “One recent afternoon, Mr. Lei walked through the village““This was our house,” he said, gesturing to a small rise of rubble and overgrown weeds. “They all lived in the streets around here. We performed at the temple.” “The temple is one of the few buildings still standing. (The Communist Party headquarters is another.) Built in the 18th century, the temple is made of wooden beams and tiled roofs, surrounded by a seven-foot wall. Its brightly painted colors have faded. The weather-beaten wood is cracking in the dry, windy Beijing air. Part of the roof has caved in, and the wall is crumbling. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, February 1, 2014]

“Evenings after work, the musicians would meet in the temple to practice. As recently as Mr. Lei’s grandfather’s generation, the performers could fill a day with songs without repeating themselves. Today, they can sing only a handful. Some middle-aged people have joined the troupe, so on paper they have a respectable 45 members. But meetings are so hard to arrange that the newcomers never learn much, he said, and performing under a highway overpass is unattractive.

“Over the past two years, the Ford Foundation underwrote music and performance classes for 23 children from migrant families from other parts of China. Mr. Lei taught them to sing, and to apply the bright makeup used during performances. Last May, they performed at the Mount Miaofeng temple fair, earning stares of admiration from other pilgrimage societies also facing aging and declining membership. But the project’s funding ended over the summer, and the children drifted away.

“One of the oddities of the troupe’s struggles is that some traditional artisans now get government support. The government lists them on a national register, organizes performances and offers modest subsidies to some. In December 2013 Mr. Lei’s group was featured on local television and invited to perform at Chinese New Year activities. Such performances raise about $200 and provide some recognition that what the group does matters.

Traditional Chinese Musical Instruments

By one count there are 400 different musical instruments, many of them associated with specific ethnic groups, still used in China. Describing the instruments he encountered in 1601 the Jesuit missionary Father Matteo Ricco wrote: there were “chimes of stone, bells, gongs, flutes like twigs on which a bird was perched, brass clappers, horns and trumpets, consolidated to resemble beasts, monstrous freaks of musical bellows, from of every dimensions, wooden tigers, with row of teeth on their backs, gourds and ocarinas".

Traditional Chinese musical string instruments include the “erhu” (a two-stringed fiddle), “ruan” (or moon guitar, a four stringed instrument used in Peking Opera), “banhu” (a string instrument with a sound box made from coconut), “yueqin” (four-stringed banjo), “huqin” (two-stringed viola), “pipa” (four-stringed pear-shaped lute), “guzheng” (zither), and “qin” (a seven-string zither similar to Japanese koto).

Traditional Chinese flutes and wind musical instruments include the “sheng” (traditional mouth organ), “sanxuan” (three-stringed flute), “dongxiao” (vertical flute), “dizi” (horizontal flute), “bangdi” (piccolo), “xun” (a clay flute that resembles a beehive), “laba” (a trumpet that imitates bird songs), “suona” (oboe-like ceremonial instrument), and the Chinese jade flute. There are also “daluo” (ceremonial gongs) and bells.

Qin

A Yueqin

J. Kenneth Moore of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: ““Endowed with cosmological and metaphysical significance and empowered to communicate the deepest feelings, the qin, a type of zither, beloved of sages and of Confucius, is the most prestigious of China's instruments. Chinese lore holds that the qin was created during the late third millennium B.C. by mythical sages Fuxi or Shennong. Ideographs on oracle bones depict a qin during the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600-1050 B.C.) , while Zhou-dynasty (ca. 1046-256 B.C.) documents refer to it frequently as an ensemble instrument and record its use with another larger zither called the se. Early qins are structurally different than the instrument used today. Qins found in excavations dating to the fifth century B.C. are shorter and hold ten strings, indicating that the music was probably also unlike today's repertoire. During the Western Jin dynasty (265 — 317), the instrument became that form which we know today, with seven twisted silk strings of various thicknesses. [Source: J. Kenneth Moore, Department of Musical Instruments, The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

“Qin playing has traditionally been elevated to a high spiritual and intellectual level. Writers of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) claimed that playing the qin helped to cultivate character, understand morality, supplicate gods and demons, enhance life, and enrich learning, beliefs that are still held today. Ming-dynasty (1368-1644) literati who claimed the right to play the qin suggested that it be played outdoors in a mountain setting, a garden, or a small pavilion or near an old pine tree (symbol of longevity) while burning incense perfumed the air. A serene moonlit night was considered an appropriate performance time and since the performance was highly personal, one would play the instrument for oneself or on special occasions for a close friend. Gentlemen (junzi) played the qin for self-cultivation.

“Each part of the instrument is identified by an anthropomorphic or zoomorphic name, and cosmology is ever present: for example, the upper board of wutong wood symbolizes heaven, the bottom board of zi wood symbolizes earth. The qin, one of many East Asian zithers, has no bridges to support the strings, which are raised above the soundboard by nuts at either end of the upper board. Like the pipa, the qin is generally played solo. Qins over a hundred years old are considered best, the age determined by the pattern of cracks (duanwen) in the lacquer that covers the instrument's body. The thirteen mother-of-pearl studs (hui) running the length of one side indicate finger positions for harmonics and stopped notes, a Han-dynasty innovation. The Han dynasty also witnessed the appearance of qin treatises documenting Confucian playing principles (the instrument was played by Confucius) and listing titles and stories of many pieces.

Pipa

J. Kenneth Moore of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The Chinese pipa, a four-string plucked lute, descends from West and Central Asian prototypes and appeared in China during the Northern Wei dynasty (386 — 534). Traveling over ancient trade routes, it brought not only a new sound but also new repertoires and musical theory. Originally it was held horizontally like a guitar and its twisted silk strings were plucked with a large triangular plectrum held in the right hand. The word pipa describes the plectrum's plucking strokes: pi, "to play forward," pa, "to play backward." [Source: J. Kenneth Moore, Department of Musical Instruments, The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

During the Tang dynasty (618-906), musicians gradually began using their fingernails to pluck the strings, and to hold the instrument in a more upright position. In the Museum's collection, a late seventh-century group of female musicians sculpted in clay illustrates the guitar style of holding the instrument. First thought to be a foreign and somewhat improper instrument, it soon won favor in court ensembles but today it is well known as a solo instrument whose repertoire is a virtuosic and programmatic style that may evoke images of nature or battle.

“Because of its traditional association with silk strings, the pipa is classified as a silk instrument in the Chinese Bayin (eight-tone) classification system, a system devised by scholars of the Zhou court (ca. 1046-256 B.C.) to divide instruments into eight categories determined by materials. However, today many performers use nylon strings instead of the more expensive and temperamental silk. Pipas have frets that progress onto the belly of the instrument and the pegbox finial may be decorated with a stylized bat (symbol of good luck), a dragon, a phoenix tail, or decorative inlay. The back is usually plain since it is unseen by an audience, but the extraordinary pipa illustrated here is decorated with a symmetrical "beehive" of 110 hexagonal ivory plaques, each carved with a Daoist, Buddhist, or Confucian symbol. This visual mixture of philosophies illustrates the mutual influences of these religions in China. The beautifully decorated instrument was probably made as a noble gift, possibly for a wedding. The flat-backed pipa is a relative of the round-backed Arabic cud and is the ancestor of Japan's biwa, which still maintains the plectrum and playing position of the pre-Tang pipa.

Chinese Zithers

An ehru

Zithers are a class of stringed instruments. The name, derived from Greek, usually applies to an instrument consisting of many strings stretched across a thin, flat body. Zithers come in many shapes and sizes, with different numbers of strings. The instrument has a long history. Ingo Stoevesandt wrote in his blog on Music is Asia: “In the tombs unearthed and dated back to 5th century BC, we find another instrument that will be unique for countries all over East Asia, existing from Japan and Korea to Mongolia or even down to Vietnam: The zither. Zithers are understood as all instruments with strings stretching along a sideboard. Within the divers ancient zithers we do not only find disappeared models like the large 25-stringed Ze or the long 5-stringed Zhu which maybe was struck instead of being plucked - we also find the 7-stringed Qin and the 21-stringed Zheng zithers which are still popular today and did not change from the first century AD until today. [Source: Ingo Stoevesandt from his blog on Music is Asia ***]

“These two models stand for the two classes of zithers one can find in Asia today: One is getting tuned by movable objects under the chord, like wooden pyramids used at the Zheng , the Japanese Koto or the Vietnamese Tranh, the other one uses tuning pegs at the end of the chord and has playing marks/frets like a guitar. Namely, the Qin was the first instrument ever using tuning pegs in the musical history of China. Even today the playing of the Qin represents the elegance and power of concentration in music, and a skilled Qin player is highly reputated. The sound of the Qin has become a worldwide trademark for “classical” China. ***

“During the Qin dynasty, while the interest in popular music was increasing, musicians were looking for a zither that was louder and more easy to transport. This is believed to be a reason for the development of the Zheng, which first appeared with 14 strings. Both zithers, Qin and Zheng, were undergoing some changes, even the Qin was known with 10 string instead of 7, but after the first century no majestic changes were applied anymore, and the instruments, which were already widespread all over China at this time, did not change until today. This makes both instruments one of the oldest instruments worldwide which are still in use. ***

“Listening to Zither Music”, by an anonymous Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) artist is ink on silk hanging scroll, measuring 124 x 58.1 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: This baimiao (ink outline) painting shows scholars in the shade of paulonia by a stream. One is on a daybed playing a zither as the other three sit listening. Four attendants prepare incense, grind tea, and heat wine. The scenery also features a decorative rock, bamboo, and an ornamental bamboo railing. The composition here is similar to the National Palace Museum’s “Eighteen Scholars” attributed to an anonymous Song (960-1279) artist, but this one more closely reflects an upper-class courtyard home. In the middle is a painted screen with a daybed in front and a long table with two backed chairs on either side. In front are an incense stand and a long table with incense and tea vessels in a refined, meticulous arrangement. The furniture types suggest a late Ming dynasty (1368-1644) date.

Guqin and Its Music

The “guqin”, or seven-stringed zither, is regarded as the aristocrat of Chinese classical music. It is more than 3,000 years. Its repertory dates back to the first millennium. Among those who played it were Confucius and the famous Chinese poet Li Bai.

The Guqin and its music was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2008. According to UNESCO: The Chinese zither, called guqin, has existed for over 3,000 years and represents China’s foremost solo musical instrument tradition. Described in early literary sources and corroborated by archaeological finds, this ancient instrument is inseparable from Chinese intellectual history. [Source: UNESCO]

Guqin playing developed as an elite art form, practised by noblemen and scholars in intimate settings, and was therefore never intended for public performance. Furthermore, the guqin was one of the four arts — along with calligraphy, painting and an ancient form of chess — that Chinese scholars were expected to master. According to tradition, twenty years of training were required to attain proficiency. The guqin has seven strings and thirteen marked pitch positions. By attaching the strings in ten different ways, players can obtain a range of four octaves.

The three basic playing techniques are known as san (open string), an (stopped string) and fan (harmonics). San is played with the right hand and involves plucking open strings individually or in groups to produce strong and clear sounds for important notes. To play fan, the fingers of the left hand touch the string lightly at positions determined by the inlaid markers, and the right hand plucks, producing a light floating overtone. An is also played with both hands: while the right hand plucks, a left-hand finger presses the string firmly and may slide to other notes or create a variety of ornaments and vibratos. Nowadays, there are fewer than one thousand well-trained guqin players and perhaps no more than fifty surviving masters. The original repertory of several thousand compositions has drastically dwindled to a mere hundred works that are regularly performed today.

Chinese Wind Instruments

Ingo Stoevesandt wrote in his blog on Music is Asia: “The ancient wind instruments may be separated in three groups, consisting of transverse flutes, panpipes and the mouth organ Sheng. Wind instruments and zithers were the first instruments which became available for the common citizen, while drums, chime stones and bell sets remained for the upper class as a symbol of reputation and richness. Wind instruments had to challenge the task to be equally tuned with the chime stones and bell sets who had a fixed tuning. [Source: Ingo Stoevesandt from his blog on Music is Asia ***]

The traverse flute represents a missing link between the old bone flute from the stone ages and the modern Chinese flute Dizi. It is one of the oldest, most simple and most popular instruments in China. The ancient panpipes Xiao reflect a musical transition beyond historical or geographical borders. This musical instrument which can be found all over the world appeared in China in the 6th century B.C. and it is believed that it first was used for hunting birds (which is still questionable). It later became the key instrument of the military music gu chui of the Han period. ***

Another outstanding instrument still used until today is the mouthorgan Sheng which we also know with the names Khen in Laos or Sho in Japan. Mouth organs like these also exist in various simple forms among the ethnicities of Southeast Asia. It remains unresearched whether the early mouth organs were functionable instruments or just grave gifts. Today, mouth organs were excavated ranging from six up to more than 50 pipes. ***

Chinese Fiddles

The erhu is probably the best known of the 200 or so Chinese stringed instruments. It gives a lot of Chinese music it high-pitched, winy, sing-songy melody. Played with a horsehair bow, it is made of a hardwood such as rosewood and has a sound box covered with python skin. It has neither frets nor a fingerboard. The musician creates different pitches by touching the string at various positions along a neck that looks like a broomstick.

The erhu is around 1,500 years old and is thought to have been introduced to China by nomads from the steppes of Asia. Featured prominently in the music for the film “The Last Emperor”, it has traditionally been played in songs with no singer and often plays the melody as if it were singer, producing rising, falling and quivering sounds. See Musicians Below.

The “jinghu” is another Chinese fiddle. It is smaller and produces a rawer sound. Made from bamboo and the skin of the five-step viper, it has three silk strings and is played with a horsehair bow. Featured in much of the music from the film “Farewell My Concubine”, it has not received as much attention is the erhu because it has traditionally not been a solo instrument

Traditional Chinese Musicians

Traditional music can be seen at the Temple of Sublime Mysteries in Fuzhou, the Xian Conservatory, the Beijing Central Conservatory and in the village of Quijaying (south of Beijing). Authentic folk music can be heard in teahouses around Quanzhou and Xiamen on the Fujian coast. Nanguan is particularly popular in Fujian and Taiwan. It is often performed by female singers accompanied by end-blown flutes and plucked and bowed lutes.

The erhu virtuoso Chen Min is one of the most famous players of classical Chinese music. She has collaborated with Yo Yo Ma and worked with a number of famous Japanese pop groups. She has said appeal of the erhu “is that the sound is much closer to the human voice and matches the sensibilities found deep in the hearts of oriental people...The sound enters the hearts easily and feels like it reacquaints us with our fundamental spirits.”

Jiang Jian Hua played the erhu on the Last Emperor soundtrack. A master of the violin as well, she has worked with the Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa, who was moved to tears the first time he heard her play as a teenager. “The Last Emperor” won an Academy Award for best soundtrack as did “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”, composed by Hunan-born Tan Dun.

Liu Shaochun is credited with keeping music of the guqin alive in the Mao era. Wu Na is regarded a one the best living performers of the instrument. On Liu’s music Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker: “It is a music of intimate addresses and subtle power that is able to suggest immense spaces, skittering figures and arching melodies” that “give way to sustained, slowly decaying tones and long, meditative pauses.”

Wang Hing is a musical archeologist from San Francisco who has traveled widely across China recording masters of traditional music playing ethnic instruments.

The soundtrack music from “The Last Emperor”, “Farewell My Concubine”, Zhang Zeming's “Swan Song” and Chen Kaige's “Yellow Earth” feature traditional Chinese music that Westerners might find appealing.

Twelve Girls Band

The Twelve Girls Band — a group of attractive young Chinese women who played rousing music on traditional instruments, highlighting the erhu — were big hits in Japan in the early the 2000s. They appeared frequently on Japanese television and their album “Beautiful Energy” sold 2 million copies in the first year after its release. Many Japanese signed for up for erhu lessons.

The Twelve Girls Band is comprised of a dozen beautiful women in tight red dresses. Four of them stand at the front of the stage and play ehru, while two play flutes and others play yangqi (Chinese hammered dulcimers), guzheng (21-string zither) and pipa (plucked five-string Chinese guitar). The Twelve Girls Band generated a lot of interest in traditional Chinese music in Japan. Only after they became successful in Japan did people become interested in them in their homeland. In 2004 they did a tour of 12 cities in the United States and performed before sold out audiences.

Dali’s Music Scene

Reporting from Yunnan in Southwest China, Josh Feola wrote in Sixth Tone: “Nestled between the expansive Erhai Lake to the east and the picturesque Cang Mountains to the west, Dali Old Town is best known as a must-see destination on the Yunnan tourism map. From near and far, tourists flock to Dali for a glimpse of its scenic beauty and its rich cultural heritage, characterized by the high concentration of Bai and Yi ethnic minorities.. But beyond and beneath the waves of people swept up in the region’s ethnic tourism industry, Dali is quietly making a name for itself as a center of musical innovation. In recent years, Dali Old Town — which sits 15 kilometers from the 650,000-strong Dali city proper — has attracted an inordinate number of musicians from both within and outside of China, many of whom are eager to document the region’s musical traditions and repurpose them for new audiences. [Source: Josh Feola, Sixth Tone, April 7, 2017]

“Dali has held a special place in the cultural imagination of young artists from across China for more than a decade, and Renmin Lu, one of its main arteries and home to more than 20 bars offering live music on any given evening, is where many of these musicians ply their trade. Though Dali has been increasingly swept up in the wave of urbanization spreading across the nation, it retains a unique sonic culture that meshes traditional, experimental, and folk music into a rustic soundscape distinct from that of China’s megacities. March 9, 2017. Josh Feola for Sixth Tone

“The desire to escape toxic city life and embrace traditional folk music led Chongqing-born experimental musician Wu Huanqing — who records and performs using just his given name, Huanqing — to Dali in 2003. His musical awakening had come 10 years earlier, when he came across MTV in a hotel room. “That was my introduction to foreign music,” he says. “At that moment, I saw a different existence.”

“The 48-year-old’s musical journey led him to form a rock band in Chengdu, in southwestern China’s Sichuan province, and — near the turn of the millennium — engage with musicians around the country who were making and writing about experimental music. But for all his forays into new territory, Wu decided that the most meaningful inspiration lay in the environment and musical heritage of rural China. “I realized that if you want to seriously learn music, it’s necessary to learn it in reverse,” he tells Sixth Tone at Jielu, a music venue and recording studio that he co-runs in Dali. “For me, this meant studying the traditional folk music of my country.”

“Since he arrived in Dali in 2003, Wu has recorded the music of the Bai, Yi, and other ethnic minority groups as something of a part-time hobby, and he has even studied the languages in which the music is performed. His most recent recordings of kouxian — a kind of jaw harp — tunes by seven different ethnic minority groups were commissioned by Beijing record label Modern Sky.

“Most notably, Dali has proven a fertile source of inspiration for Wu’s own music, influencing not only his compositions but also the building of his own instruments. From his base of operations, Jielu, he crafts his own musical language around the timbres of his homemade arsenal: mainly five-, seven-, and nine-stringed lyres. His music ranges from ambient soundscapes incorporating environmental field recordings to delicate vocal and lyre compositions, evoking the textures of traditional folk music while remaining something entirely his own.

For the rest of the article See MCLC Resource Center /u.osu.edu/mclc

Image Sources: Nolls http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html , except flutes (Natural History magazine with artwork by Tom Moore); Naxi orchestra (UNESCO) and Mao-era poster (Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021