EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA

4th century reliefs of apsara from Yungang Caves

It is widely believed that Buddhism was introduced to China during the Han period (206 B.C.- A.D. 220). Buddhism entered China, perhaps as early as the first century B.C., from India and Central Asia via the Silk Road trade route, along which goods were traded between China and the Roman Empire and cultures from China merged with those of India, Central Asia and Iran. Artifacts from Kushan — a Greek-influenced, Pakistan-based, Buddhist civilization — have been found in western China. In the A.D. 1st century Buddhism caught they eye of the Han Emperor Wu, who sent a mission to India which returned in A.D. 67 with Buddhist scriptures, two Indian monks and several Buddhist images. By the end of the A.D. 1st century there was a Buddhist community in the Chinese capital of Loyang.

Buddhism didn't really begin to have an influence on China until the A.D. 2nd century, when Buddhist monks and translator-missionaries from India and Central Asia began arriving in larger numbers overland along the Silk Road and by sea on trade routes between India and China via Southeast Asia. The first Buddhist monks arrived with shaven heads, begging bowls and robes at a time when the only people in China that dressed and acted in such a manner were criminals and beggars. These monks, traveling alone and in pairs, had nether homes nor families — concepts that defied traditional Confucian emphasis on family, honoring ancestors and producing heirs. The earliest Buddhist monasteries in China were run primarily by Chinese-speaking Indians and Central Asians. As their Chinese students matured Chinese took over the monasteries and Buddhist texts translated to Chinese became the main texts.

Buddhism arrived in China at roughly the same time Christianity was spreading from Palestine into the Roman Empire. Unlike Christianity in Europe, Buddhism in China was never able to wipe out traditional moral and religious beliefs that existed before it. At first Buddhism was viewed as just another Taoist sect. Stories circulated that the Taoist founder Lao-tze emigrated to the West and became a teacher of The Buddha or became The Buddha himself.

There have been periods where Buddhists in China have been persecuted. Perry Garfinkel wrote in National Geographic: “In China, in A.D. 842, the Tang Emperor Wuzong began to persecute foreign religions. Some 4,600 Buddhist monasteries were annihilated, priceless works of art were destroyed, and about 260,000 monks and nuns were forced to return to lay life. History repeated itself with the Chinese Communist Party's attempt to suppress Buddhism — most visibly in Tibet. According to the International Campaign for Tibet, since 1949 more than 6,000 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, nunneries, and temples have been destroyed and at least 500,000 Tibetans have died from imprisonment, torture, famine, and war. But today Buddhism in China, like the lotus flower that emerges from mud, is resurfacing. With more than 100 million practitioners, it's one of the country's fastest growing religions. [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005]

Websites and Resources on Buddhism in China Buddhist Studies buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in China Wikipedia Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ;

Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ;

East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; Mahayana Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ;

The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ;

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ; Chinese Religion and Philosophy: Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LOTUS SUTRA AND THE DEFENSE OF BUDDHISM AGAINST CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com; CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES, MONKS AND FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHISM TODAY factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM VERSUS THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey” by Kenneth Ch'en Amazon.com; “Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China” by Christine Mollier Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; “China Root: Taoism, Ch'an, and Original Zen” by David Hinton Amazon.com; Buddhism Between Tibet and China” Matthew Kapstein Amazon.com; “The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang” by Sally Hovey Wriggins Amazon.com; “Xuanzang: China's Legendary Pilgrim and Translator”by Benjamin Brose Amazon.com; “Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Faxian and James Legge Amazon.com; Schools of Buddhism in China: “Chan Buddhism” by Peter D. Hershock Amazon.com; “The Essence of Chan: A Guide to Life and Practice according to the Teachings of Bodhidharma” by Guo Gu (Author) Amazon.com; “Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice” by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com; Famous Sutras: “The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic” by Gene Reeves Amazon.com; “The Lotus Sutra” by Burton Watson Amazon.com; “The Diamond Sutra” by Red Pine Amazon.com; Buddhist Art: “The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com; “Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road” by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al. Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road” by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com

Buddhism as a Religion Imported to and Exported from China

Portable Buddhist shrine used in the transport of Buddhism to and from China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Buddhism is an interesting form of Chinese religion for many reasons, not least because it was the first major religious tradition in China that was “imported” from abroad. (Other forms of Buddhism from Tibet and Mongolia, Christianity in different guises, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Islam would follow later.) Long after Buddhism had become a natural part of the Chinese religious landscape, many Chinese — Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike — still pondered the significance of the foreign origin of the religion. [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

China was the only Buddhist country that possessed a civilization before the introduction of Buddhism. For over a thousand years Buddhism dominated religious life in China, having both a profound impact on China and Buddhism and producing a great body of literature and art. China was the conduit through which Buddhism reached Korea, Japan and Vietnam. The Buddhism found in China is almost exclusively Mahayana.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “, Buddhism is an Indian system of thought that was transmitted to China by Central Asian traders and Buddhist monks as early as the first century A.D. Later it passed into Korea by the fourth century and Japan by the sixth. Its influence on all three cultures was enormous... Buddhism, in its long history, branched into many competing philosophical schools, religious traditions, and monastic sects. There are literally dozens of very different versions of Buddhism in East Asian history and in the world today (although, oddly, Buddhism died out in its native India at a rather early date). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/]

Within China, Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Regional variation in the material trappings of Buddhism should be kept in mind. The biggest divide is between areas where Tibetan Buddhism is dominant (Tibet, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia predominantly), and other regions of China. Buddhism arrived in Tibet by a different route, primarily from India, and although there was much interchange between Tibetan Buddhism and schools of Buddhism in Tang and later China, many differences in both doctrine and practice have persisted until today. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

Origin of Buddhism in India-Nepal

Ajanta Buddha from AD 4th century IndiaDr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The founder of Buddhism was a prince of a North Indian tribe who lived about the year 500 B.C. (about the time of Confucius in China)” in present-day Nepal. “His name was Siddhartha Gautama and he was a member of the Shakya tribe; he is often called Shakyamuni. His religious name, the Buddha, means “the awakened one,” and at the heart of the Buddha's teaching was a call to people to adopt certain practices that would show them that they were living in such deep ignorance that they could be said to be asleep to the truth..only those who followed the Buddha's path could awaken to reality. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“During the Buddha's lifetime, as later, the predominant religious tradition of India was Hinduism, a religion that includes an extensive array of devotional practices that bring people closer to a world of superhuman gods, and also a strong strain of ascetic self-cultivation practices, including many forms of yoga, that are designed to purify the soul and bring the person closer to an ideal state of being. Among Hinduism's many complex features is a belief in the “transmigration of souls”: that is, the idea that after our physical death, our eternal soul migrates to a new form, through which it is physically “reincarnated.” /+/

“Siddhartha Gautama's teachings grew from an unusual mid-life crisis. Sheltered by his royal family from all the pain and suffering of life while young, an unexpected encounter with the miseries suffered by others shocked the adult Gautama into a radically new view of human existence, a perspective from which only suffering seemed real and all the comforts to which he was accustomed seemed an illusion. Disillusioned with palace life, he left to follow the example of Hindu yogins, retreating to the forests of North India to lead a life of meditation and self-denial. In the wilderness, Gautama developed new methods for meditation and a new vision of life, mind, and the universe. These form the core of the philosophy of Buddhism. /+/

“The Buddha's Core Ideas, When Gautama emerged from the forest as the newly enlightened Buddha he immediately began to preach his revelations: the Buddhist law of truth, or the "Dharma". While the many different schools of Buddhism each have their own versions of exactly what the Buddha said, and there are many points of disagreement, some points are agreed upon by virtually everyone.” /+/

Arrival of Buddhism in China

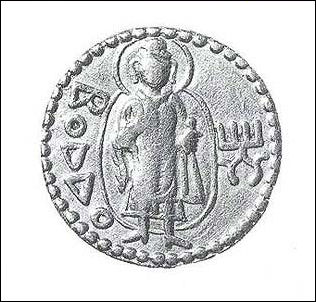

Kushan coin from 100 BC,

earliest surviving Buddha image,

from Pakistan

Buddhism entered China, perhaps as early as the first century B.C., from India and Central Asia via the Silk Road trade route, along which goods were traded between China and the Roman Empire and cultures from China merged with those of India, Central Asia and Iran. Artifacts from Kushan — a Greek-influenced, Pakistan-based, Buddhist civilization — have been found in western China. In the A.D. 1st century Buddhism caught they eye of the Han Emperor Wu, who sent a mission to India which returned in A.D. 67 with Buddhist scriptures, two Indian monks and several Buddhist images. By the end of the A.D. 1st century there was a Buddhist community in the Chinese capital of Loyang.

Buddhism probably also entered China to some degree from the south coast from merchants and others from India. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: According to Indian customs, Brahmans, the Hindu caste providing all Hindu priests, could not leave their homes. As merchants on their trips which lasted often several years, did not want to go without religious services, they turned to Buddhist priests as well as to priests of Near Eastern religions. These priests were not prevented from travelling and used this opportunity for missionary purposes. Thus, for a long time after the first arrival of Buddhists, the Buddhist priests in China were foreigners who served foreign merchant colonies. The depressed conditions of the people in the second century A.D. drove members of the lower classes into their arms, while the parts of Indian science which these priests brought with them from India aroused some interest in certain educated circles. Buddhism, therefore, undeniably exercised an influence at the end of the Han dynasty, although no Chinese were priests and few, if any, gentry members were adherents of the religious teachings. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ The propositions of Buddhism were articulated originally in the context of traditional Indian cosmology in the first several centuries B.C., and as Buddhism began to trickle haphazardly into China in the first centuries of the common era (CE), Buddhist teachers were faced with a dilemma. To make their teachings about the Buddha understood to a non-Indian audience, Buddhist teachers often began by explaining the understanding of human existence — the problem, as it were — to which Buddhism provided the answer. [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ]

Prior to the arrival of Buddhism in China, there had been no major form of Chinese thought that viewed life, the concrete world, and the human body in so pessimistic a way as Buddhism. One of the earliest Chinese Buddhist meditation texts, dating from the third century, instructs mediators to ponder the corrupt and painful nature of life in a human body: “The ascetic engages in contemplation of himself and observes that all the noxious seepage of his internal body is impure. Hair, skin, skull and flesh; tears from the blinking of the eyes and spittle; veins, arteries, sinew and marrow; liver, lungs, intestines and stomach; feces, urine, mucus and blood: such a mass of filth when combined produces a man. It is as if a sack were filled with a leaky bag.” (Quoted in Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed., The Buddhist Tradition in India, China, and Japan [New York: The Modern Library, 1969], p. 129.) [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Buddhism During the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.– A.D. 220)

Portable Chinese Buddhist shrine

Mario Poceski wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”: Buddhism first entered China around the beginning of the common era, during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 c.e.). The first Buddhist missionaries arrived through the empire's northwestern frontier, accompanying merchant caravans that traversed the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road, which linked China with Central Asia and Persia, with additional links to West and South Asia. By that time Buddhism had already establish a strong presence within the Central Asian kingdoms that controlled most of the trade along the Silk Road. Early literary evidence of Buddhism's entry into China links the foreign religion with the Han monarchy and its ruling elites. Such connection is explicit in the well-known story about Emperor Ming's (r. 58–75 c.e.) dream about a golden deity, identified by his advisers as the Buddha. That supposedly precipitated the emperor's sending of a western-bound expedition that brought back to China the first Buddhist text (and two missionaries, according to a later version of the story). Taking into consideration the court-oriented outlook of traditional Chinese historiography, such focus on the emperor's role in the arrival of Buddhism should not come as a surprise. However, in light of the prevalent patterns of economic and cultural interaction between China and the out-side world during this period, it seems probable that Buddhism had already entered China prior to Emperor Ming's reign. [Source: Mario Poceski, “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

“Most of the early Buddhist monks who entered China were associated with the Mahayana tradition, which was increasing in popularity even while it was still undergoing creative doctrinal development. The foreign missionaries—most of whom were Kushans, Khotanese, Sogdians, and other Central Asians—entered a powerful country with evolved social and political institutions, long-established intellectual and religious traditions, and a profound sense of cultural superiority. In the course of the initial contacts, some members of the Chinese elites found the new religion to be inimical to the prevalent social ethos. The institution of monasticism, with its stress on ascetic renunciation, which included celibacy and mendicancy, was alien to the Chinese and went against the Confucian-inspired mores adopted by the state and the ruling aristocracy.

“In response to the initial spread of the alien religion, some Chinese officials articulated a set of critiques that highlighted perceived areas of conflict between Buddhism and the prevalent Confucian ideology. The principal object of the criticisms was the monastic order (san˙gha). Buddhist monks were accused of not being filial because their adoption of a celibate lifestyle meant they were unable to produce heirs and thereby secure the continuation of their families' lineages. Additional criticisms were leveled on economic and political grounds. Monks and monasteries were accused of being unproductive and placing an unwarranted economic burden on the state and the people, while the traditional Buddhist emphasis on independence from the secular authorities was perceived as undermining the traditional authority of the emperor and subverting the established sociopolitical system. From a doctrinal point of view, Buddhism was perceived as being overtly concerned with individual salvation and transcendence of the mundane realm, which went counter to the pragmatic Confucian emphasis on human affairs and sociopolitical efficacy. Finally, Buddhism met dis-approval on account of its foreign origin, which in the eyes of its detractors made it unsuitable for the Chinese.

Buddhism's Entry into China

Gilded bronze Buddha from 4th century China

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The entry of Buddhism in China was very likely brought about by the vast expansionist policies of a single Chinese emperor: the Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty (reigned 140-87 B.C.). Emperor Wu was the first Chinese ruler to push his armies through Central Asia, and he brought China into contact with many peoples who had previously been exposed only to cultural influences from Persia and India. Once the Han Dynasty armies had created a secure pathway from China into Central Asia, merchants from among these groups began to travel to China to trade, and this cross.Asiatic trade grew into a steady commercial stream along what became known as the Silk Road. In time, missionary Buddhist monks searching for new worlds of sentient beings to convert to their faith, began to travel along with these caravans, eventually arriving in China during the first century A.D. They carried with them not only their knowledge, but copies of the holy word of the Buddha: "sutras". /[Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“When the first Buddhist monks arrived in China, the Confucian Han Dynasty was still firmly in control of a unified state. The monks, who had come from India and a variety of Central Asian states, were of interest for their exotic dress, languages, and because Han Confucians were fascinated by texts of any kind. However, China was at that time ideologically and politically stable and Buddhism found no ready audience there. During the late second century, however, the Han state began to crumble and social disorder began to appear. Life grew increasingly uncertain. After 220, China was once again divided into warring independent kingdoms, as had been true of the late Zhou many years earlier, and the Confucian ideology of the Han empire fell rapidly into disrepute. /+/

“The decline of Confucianism set off a search among the most educated scholars in China for new systems of thought that could provide answers appropriate to those dislocated times. During the third century, many of these people found the ideology they were looking for in the thought of Zhuangzi, whose descriptions of the boundless Dao and of unconventional heroes possessing quirky skills appealed very much to the jaded tastes of the privileged class. Members of this upper elite produced a set of eccentric writings, artistic works, and social conventions (or counter-conventions) that are known now as “Neo.Daoism.” We will look briefly at Neo.Daoism further in our next reading, but for now, the interest Neo.Daoism holds for us lies in the fact that it was the Neo-Daoists who first began to pay serious attention to the learning of the foreign monks who had been arriving from Central Asia for over a century, often taking up permanent residence in the major cities of China. /+/

“The Neo-Daoists and like-minded intellectuals began to work with Buddhist monks to translate the "sutras" which the monks had brought with them. We still possess these early translations, and it is very clear both that the monks made some effort to express the texts in Daoistic language that would appeal to the Chinese, and that the Chinese interpreted the texts as a sort of Daoist exotica. As a result, in a very brief time poorly translated Buddhist “sutras“ had 7, become a major intellectual fad, especially in southern China, where wars and social upheavals had driven many wealthy Chinese families as displaced refugees. So deep was the Chinese misreading of Buddhism, that a widely accepted “historical fact” of the time was that the Buddha was actually Laozi, who, it appeared, towards the close of his (fictional) life, wandered off westwards with his “Dao de jing” in hand in order to “convert the barbarians,” who apparently mistook him for a North Indian prince. According to this point of view, Buddhist scripture was nothing other than the “Dao de jing”, volumes 2.10,000. /+/

“Although the Neo-Daoists misunderstood Buddhism, their patronage of Buddhist monks was a turning point in Chinese cultural history. In time, their support of individual Buddhists and of the establishment of Buddhist monasteries attracted increasing numbers of monks from the west, many of whom were more deeply schooled in emerging trends of Buddhist doctrine. As these immigrant monks began to produce sophisticated translations closer to the spirit of Buddhism, their Chinese audiences came better to understand the nature of Buddhism, and increasing numbers of educated Chinese youths, despairing at the prolonged civil chaos that surrounded them, withdrew from Chinese society and became Buddhist monks. By the end of the fourth century, native Chinese monks, though still dependent upon foreign tutors and translators, were establishing their own monastic communities and producing original doctrinal interpretations for a Chinese audience. /+/

Buddhism During the Six Dynasties Period (A.D. 220-589)

Mario Poceski wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”: “Despite these misgivings, by the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 Buddhism had managed to gain a foothold in China. Its growth sharply accelerated during the period of disunion (311–589), the so-called Six Dynasties period, which constitutes the second phase of Buddhist history in China. It was an age of political fragmentation as non-Chinese tribes established empires that ruled the north, while the south was governed by a series of native dynasties. Ironically, the unstable situation encouraged the spread of Buddhism. In the eyes of many educated Chinese the collapse of the old imperial order brought discredit to the prevailing Confucian ideology, which created an intellectual vacuum and a renewed sense of openness to new ideas. [Source: Mario Poceski, “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Buddhism was also attractive to the non-Chinese rulers in the north, who were eager to use its universalistic teachings in their search for political legitimacy. Another contributing factor was the growing interest in religious and philosophical Daoism. Many upper-class Chinese who were familiar with Daoist texts and teachings were drawn to Buddhism's sophisticated doctrines, colorful rituals, and vast array of practices, including meditation. Buddhist teachings and practices bore reassuring (if often superficial) resemblance to those of Daoism, while they also provided original avenues for spiritual growth and inspiring answers to questions about ultimate values. The growth of Buddhism was further enhanced by the adaptability of the Mahayana traditions that were imported into China. The favorable reception of Buddhism was greatly aided by its capacity to be responsive to native cultural norms, sociopolitical demands, and spiritual predilections, while at the same time retaining fidelity to basic religious principles.

“During the period of division, Buddhism in the north was characterized by close connections between the clergy and the state, and by interest in thaumaturgy, asceticism, devotional practice, and meditation. In contrast, the south saw the emergence of so-called gentry Buddhism. Some southern elites (a group that included refuges from the north) who were interested in metaphysical speculation were especially attracted to the Buddhist doctrine of ŚŪnyatĀ (empti-ness), which was often conflated with Daoist ideas about the nature of reality. The southern socio-religious milieu was characterized by close connections between literati-officials and Buddhist monks, many of whom shared the same cultured aristocratic background. Despite two anti-Buddhist persecutions during the 452–466 and 547–578 periods, by the sixth century Buddhism had established strong roots throughout the whole territory of China, and had permeated the societies and cultures of both the northern and the southern dynasties. Moreover, Chinese Buddhism was exported to other parts of East Asia that were coming under China's cultural influence, above all Korea and Japan.

Faxian

Faxian at Ashoka Palace in India

Between A.D. 399 and 414, the Chinese monk Faxian (Fa-Hsien, Fa Hien) undertook a trip via Central Asia to India to study Buddhism, locate sutras and relics in India and obtain copies of Buddhist books than were currently available in China. He traveled from Xian to the west overland on the southern Silk Road into Central Asia and described monasteries, monks and pagodas. He then crossed over Himalayan passes into India and ventured as far south as Sri Lanka before sailing back to China on a route that took him through present-day Indonesia. His entire journey took 15 years.

Tansen Sen wrote in Education about Asia: “Faxian was one of the first and perhaps the oldest Chinese monk to travel to India. In 399, when he embarked on his trip from the ancient Chinese capital Chang’an (present- day Xi’an in Shaanxi province), Faxian was more than sixty years old. By the time he returned fourteen years later, the Chinese monk had trekked across the treacherous Taklamakan desert (in present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China), visited the major Buddhist pilgrimage sites in India, traveled to Sri Lanka, and survived a precarious voyage along the sea route back to China. [Source: Tansen Sen, Education about Asia, Volume 11, Number 3 Winter 2006]

“The opening passage of Faxian’s "A Record of the Buddhist Kingdoms" tells us that the procurement of texts related to monastic rules (i.e., “Vinaya”) was the main purpose of his trip to India. In addition to revealing the intent of his trip, the statement also underscores the need for this crucial Buddhist literature in contemporary China. In the third and fourth centuries, a number of important Buddhist texts, including the “Lotus Sutra”, had been translated into Chinese. Although a few “Vinaya” texts were available to Faxian, the growing Buddhist community in China was aware of the paucity of these texts essential for the establishment and proper functioning of monastic institutions.”

See Separate Articles FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA, CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN IN INDIA factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN’S RETURN TRIP FROM INDIA TO CHINA factsanddetails.com

Growth of Buddhism in China in the Six Dynasties Period (A.D. 220-589)

Buddhism developed and spread rapidly in the chaos of the Six Dynasties Period (A.D. 220-589) that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty in A.D. 220. The seeking of nirvana and peace and other Buddhist doctrines seemed like nice ideas at a time when China was a violent and dangerous place. Interest in Buddhism also grew as Silk Road trade stimulated an interest in exotic things and monk-sponsored welfare projects attracted devotees from many social strata. At times Buddhism prospered under imperial patronage. At times its foreign origin led it to be singled out for major persecutions.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “After its introduction, Mahayana Buddhism, the most prominent branch of Buddhism in China, played an important role in shaping Chinese civilization. Chinese civilization, as well, exerted a profound impact on the way Buddhism was transformed in China. The influence of Buddhism grew to such an extent that vast amounts of financial and human resources were expended on the creation and establishment of impressive works of art and elaborate temples. This growing interest in Buddhism helped to inspire new ways of depicting deities, new types of architectural spaces in which to worship them, and new ritual motions and actions. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “China's post-Han “period of disunity” lasted from A.D. 220 until 589, and from the mid-point of this period on, the growth of Buddhism was phenomenal. Several Chinese kingdoms adopted Buddhism as their religion of state and patronized monks and monasteries lavishly. Varieties of Mahayana schools imported from India took root in China, each with its own signature “sutra”, representing the Buddha's “ultimate” teaching, which superseded the teachings of all other schools. Chinese pilgrims traveled to Central Asia and India and brought back “sutra”after “sutra”, every one recording the “authentic” words of Siddhartha Gautama. Chinese monks and lay followers began to create innovative new interpretive traditions and demonstrated their full membership in the world Buddhist community by writing their own “sutras”, which, after all, were just as much the authentic words of the Buddha as the Sanskrit “sutras”coming from India (and much easier for Chinese to read!). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

6th century stone Buddha from Maijishan

By the A.D. 3rd century the Chinese monk community had become consolidated and Buddhist missionaries began moving around China. By and large they were welcomed. Buddhism caught on most quickly in northern China, where the belief was patronized by a number of rulers, and spread southward with the migration of Han Chinese. During the 4th century, when China was engulfed in war and the northern areas were overrun by horsemen from Mongolia, Buddhism was the dominant faith in China. By that time Buddhist missionaries had not only spread their religion to the far corners of China they had also made inroads into imperial court in Nanking.

By the 5th century Buddhism was well patronized in many Chinese state; sutras in Chinese were widely circulated; and their meanings were debated, giving rise to the first schools. The earliest-surviving Buddhist art from China — in cave shrines in Xinjiang and Yunkang near the Great Wall — date from this period. By medieval times the Sanga system of patronage — where the rich helped the monasteries and the monasteries helped educate the masses — was firmly entrenched.

Buddhism began to flourish in China during the Northern and Southern dynasties (A.D. 386-589). During the 6th century, Chinese Buddhism was consolidated and standardized. Great schools were founded that boasted thousands of disciples. Schools with royal patrons built huge monasteries. Between A.D. 476 and 540 the number temples rose from 6,500 to 30,900 and the number of monks and nuns grew from 80,000 to 200,000 (out of a population of 50 million).

Dr. Eno wrote: “By the end of the period of disunity, Daoism had been completely overshadowed by Buddhism (indeed, new and unusual religious forms of Daoism had arisen during this period which owed a great many of their ideas to Buddhism). China was covered with Buddhist shrines, many comprising large temple complexes that included living quarters for monks and nuns, temples where lay visitors worshiped images of Buddhist deities, pavilions and courtyards where religious festivals, parades, and carnival markets were held, and towering pagodas that lifted the image of the religion over the landscape.

Model Stupa Found in Nanjing Said to Hold Buddha’s Skull

In June 2016, archaeologists announced that may have discovered what they said might be a skull bone from the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. The bone was found inside a model of a stupa (mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics) used for meditation. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “The research team found the 1,000-year-old model within a stone chest in a crypt beneath a Buddhist temple in Nanjing” in eastern China. “Inside the stupa model archaeologists found the remains of Buddhist saints, including a parietal (skull) bone that inscriptions say belonged to the Buddha himself. The model is made of sandalwood, silver and gold, and is covered with gemstones made of crystal, glass, agate and lapis lazuli, a team of archaeologists reported in an article published in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics...An article detailing the discoveries was published in Chinese in 2015 in the journal Wenwu, before being translated and published in Chinese Cultural Relics. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 1, 2016 |=|]

6th century Buddha from northern Qi

“The 1,000-year-old stupa is made of sandalwood, silver and gold. Inscriptions engraved on the stone chest that the model was found in say that it was constructed during the reign of Emperor Zhenzong (A.D. 997-1022), during the Song Dynasty. Also inscribed on the stupa are the names of people who donated money and material to build the model, as well as some of the people who constructed the model. While the inscriptions say that the skull bone belongs to the Buddha, it is unknown whether it really does come from him. In the journal article, archaeologists didn’t speculate on how likely it is. The bone is being treated with great respect and has been interred in the modern-day Qixia Temple by Buddhist monks. |=|

“Discovered beneath the Grand Bao’en Temple, the stupa model — which is 117 centimeters tall and 45 cm wide (nearly 4 feet by 1.5 feet) — was stored within an iron box, which, in turn, was stored within a stone chest. An inscription found within the stone chest was written by a man named Deming about 1,000 years ago, saying that he is “the Master of Perfect Enlightenment, Abbot of Chengtian Monastery [and] the Holder of the Purple Robe” (as translated by researchers in the journal article). He tells the story of how the Buddha’s parietal bone came to China. |=|

“Deming wrote that after the Buddha “entered parinirvana” (a final death that breaks the cycle of death and rebirth), that his body “was cremated near the Hirannavati River” in India. The man who ruled India at the time, King Ashoka (reign 268-232 B.C.), decided to preserve the Buddha’s remains, which he “divided into a total of 84,000 shares,” Deming wrote. “Our land of China received 19 of them,” including the parietal bone, he added. The parietal bone was kept in a temple that was destroyed about 1,400 years ago during a series of wars, Deming wrote. “The foundation ruins … were scattered in the weeds,” Deming wrote. “In this time of turbulence, did no one care for Buddhist affairs?” Emperor Zhenzong agreed to rebuild the temple and have the Buddha’s parietal bone, and the remains of other Buddhist saints, buried in an underground crypt at the temple, according to Deming’s inscriptions. They were interred on July 21, 1011 A.D., in “a most solemn and elaborate burial ceremony,” Deming wrote. |=|

“Deming praised the emperor for rebuilding the temple and burying the Buddha’s remains, wishing the emperor a long life, loyal ministers and numerous grandchildren: “May the Heir Apparent and the imperial princes be blessed and prosperous with 10,000 offspring; may Civil and Military Ministers of the Court be loyal and patriotic; may the three armed forces and citizens enjoy a happy and peaceful time .”

“The parietal bone of the Buddha was buried within an inner casket made of gold, which, in turn, was placed in an outer casket made of silver, according to the archaeologists. The silver casket was then placed inside the model of the stupa. The gold and silver caskets were decorated with images of lotus patterns, phoenix birds and gods guarding the caskets with swords. The outer casket also has images of spirits called apsaras that are shown playing musical instruments. The parietal bone of the Buddha was placed within the gold inner casket along with three crystal bottles and a silver box, all of which contain the remains of other Buddhist saints. Engraved on the outside of the model are several images of the Buddha, along with scenes depicting stories from the Buddha’s life, from his birth to the point when he reached “parinirvana,” a death from which the Buddha wasn’t reborn — something that freed him from a cycle of death and rebirth, according to the Buddhist religion. |=|

“A large team of archaeologists from the Nanjing Municipal Institute of Archaeology excavated the crypt between 2007 and 2010; they were supported by experts from other institutions in China. Although the excavations received little coverage by Western media outlets, they were covered extensively in China. Chinese media outlets say that, after the parietal bone of the Buddha was removed, Buddhist monks interred the bone and the remains of the other Buddhist saints in Qixia Temple, a Buddhist temple used today. The Buddha’s parietal bone and other artifacts from the excavation were later displayed in Hong Kong and Macao. When the bone traveled to Macao in 2012, the media outlet Xinhua reported that “tens of thousands of Buddhist devotees will pay homage to the sacred relic,” and that “more than 140,000 tickets have been sold out by now, according to the [event organizer].”“ |=|

Buddhism Versus Taosim and Confucianism in the Six Dynasties Period

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Non-Chinese royal houses in the North, who had little understanding of the Chinese tradition, were far more subject to being influenced by non-Chinese systems of thought, particularly Buddhism, which, during the Six Dynasties period, became the most dynamic intellectual force in China. Although Buddhism was influential in both North and South, some Northern states adopted it as official religious doctrine, while in the south, Buddhism traditions were less associated with the state, and more closely related to the intellectual interests of the elite. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

The Buddha, Laozi and Confucius

“Buddhism’s rise did not become dramatic immediately after the fall of the Han, although the misadventures of the late Han and the aftermath of the unseemly battles between Confucians and eunuchs had seriously undermined the influence of Confucian traditions. During the early years of the Six Dynasties period, cynicism about Confucian ideas led many members of the educated class to turn increasingly to Daoist books. At the same time, the uncertainties of official life led some of the best of these men to withdraw from politics and concentrate on the cultivation of refined tastes and lofty ideas, which they shared only with like-minded circles of intimates. /+/

“These Daoistically inclined cliques produced some of the most individualistic literature ever written in China. Freed from the constraints of Confucianism and its belief in the social nature of man, these Neo-Daoists came to value spontaneity and eccentricity to a degree that Confucianism could not tolerate. Often living apart from society, these men concentrated on the skills of poetry, music, and painting, and particularly celebrated the effects of wine in enhancing positions at court cultivated a separate sphere of unrestrained aesthetic abandon. /+/

“As in the Dark Ages of Europe, during which Christianity grew to become the dominant theme of European culture, the Six Dynasties Period saw the sudden flourishing of a religious movement: Buddhism, which swept into China from India and transformed both popular and elite views of the world. From the sixth century through the eighth century, Buddhism was unquestionably the dominant philosophy and religion of China. But its popularity was initially made possible only because of the affinities which intellectually prominent Neo-Daoists felt for the new religion, which in superficial ways resembled Daoism. /+/

“Neo-Daoism was also instrumental in re-introducing the human arts into the Confucian ideal of the gentleman, or “literatus.” When Confucianism came once again to the forefront after 589, the year in which the short-lived Sui Dynasty reunited China, it incorporated into its ideal persona much of the devotion to spontaneous poetry, painting, music—and occasionally wine—that the Neo-Daoists had stressed. The most famous Neo-Daoists were the “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove,” a group of eccentric geniuses who, in popular imagination at least, formed the most brilliant circle of literati” and represented “the unorthodox tone of Neo-Daoist society during the period of disunity.” Among the three most well-known ones were: Ruan Ji (210-263),Xi Kang (223-262), who was executed as a threat to public morality, and Liu Ling (d. after 265).” /+/

Mouzi's Disposing of Error: A Response to Critics of Buddhism in China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Indian religion of Buddhism began to enter China via trade routes during the later years of the Eastern Han dynasty (A.D. 25-220). The teachings and practices of Buddhism were quite different from those of Chinese civilization and contrasted with the teachings of the Confucian and Daoist philosophers whom the Chinese held in high regard. Nonetheless, Buddhism appealed to enough people to pose a challenge to those who disapproved of or had doubts about the new religion. Those doubts are addressed in this essay, constructed as a conversation between Mouzi and a critic of Buddhism. Mouzi, who may have been the author of this essay, was originally a Confucian scholar and official. Disturbed by the chaotic atmosphere of the later years of the Eastern Han, Mouzi retreated to his home in the southwestern Guangxi province to study Buddhism and Daoism. In this essay, he responds to the critics of Buddhism. [Source:Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Why Should a Chinese Allow Himself to Be Influenced by Indian Ways? “ This was one of the objections most frequently raised by Confucians and Daoists once Buddhism had acquired a foothold on Chinese soil. The Chinese apologists for Buddhism answered this objection in a variety of ways. Here we see one of the arguments used.

Mouzi’s “Disposing of Error” (Lihuo Lun) answers this question by saying: “Confucius said, ‘The barbarians with a ruler are not so good as the Chinese without one.’ [“Analects” 3:5] Mencius criticized Chen Xiang for rejecting his own education to adopt the ways of [the foreign teacher] Xu Xing, saying, ‘I have heard of using what is Chinese to change what is barbarian, but I have never heard of using what is barbarian to change what is Chinese.’ [“Mencius” 3A:4] You, sir, at the age of twenty learned the Way of Yao, Shun, Confucius, and the Duke of Zhou. But now you have rejected them and instead have taken up the arts of the barbarians. [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 421-426; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Is this not a great error?” Mouzi said … “What Confucius said was meant to rectify the way of the world, and what Mencius said was meant to deplore one-sidedness. Of old, when Confucius was thinking of taking residence among the nine barbarian nations, he said, ‘If a noble person dwells in their midst, what rudeness can there be among them?’[“Analects” 9:13] … The commentary says, ‘The north polar star is in the center of Heaven and to the north of man.’ From this one can see that the land of China is not necessarily situated under the center of Heaven. According to the Buddhist scriptures, above, below, and all around, all beings containing blood belong to the Buddha-clan. Therefore I revere and study these scriptures. Why should I reject the Way of Yao, Shun Confucius, and the Duke of Zhou? Gold and jade do not harm each other, crystal and amber do not cheapen each other. You say that another is in error when it is you yourself who err.”

Mouzi's Disposing of Error: Why Is Buddhism Not Mentioned in the Chinese Classics?

The passage from “Mouzi’s Disposing of Error” (Lihuo Lun) on “Why Is Buddhism Not Mentioned in the Chinese Classics?” reads: “The questioner said, “If the way of the Buddha is the greatest and most venerable of ways, why did Yao, Shun, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius not practice it? In the Seven Classics one sees no mention of it. There are several different lists of the Seven Classics. One found in the “History of the Latter Han” includes the “Odes”, “Documents”,”Rites”, “Music”,”Changes”, “Spring and Autumn Annals”, and the “Analects of Confucius”.] You, sir, are fond of the “Classic of Odes” and “Classic of Documents”, and you take pleasure in the “Rites” and “Music.” Why, then, do you love the way of the Buddha and rejoice in outlandish arts? Can they exceed the Classics and commentaries and beautify the accomplishments of the sages? Permit me the liberty, sir, of advising you to reject them.” [[Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 421-426; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Mouzi said, “All written works need not necessarily be the words of Confucius, and all medicine does not necessarily consist of the formulae of Bian Que [The most famous physician of antiquity]. What accords with rightness is to be followed, what heals the sick is good. The gentleman.scholar draws widely on all forms of good and thereby benefits his character. Zigong [A prominent disciple of Confucius] said, ‘Did the Master have a permanent teacher?’[Analects” 19:22] Yao served Yin Shou; Shun served Wucheng; the Duke of Zhou learned from Lü Wang; and Confucius learned from Laozi. And none of these teachers is mentioned in the Seven Classics. Although these four teachers were sages, to compare them to the Buddha would be like comparing a white deer to a "qilin" [a mythical beast like the unicorn] or a swallow to a phoenix. Yao, Shun, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius learned even from such teachers as these. How much less, then may one reject the Buddha, whose distinguishing marks are extraordinary and whose superhuman powers know no bounds! How may one reject him and refuse to learn from him? The records and teachings of the Five Classics do not contain everything. Even if the Buddha is not mentioned in them, what occasion is there for suspicion?”

Mouzi's Disposing of Error: Questions About Monks

“Why Do Buddhist Monks Do Injury to Their Bodies?” One of the greatest obstacles confronting early Chinese Buddhism was the aversion of Chinese society to the shaving of the head, which was required of all members of the Buddhist clergy. The Confucians held that the body is the gift of one’s parents and that to harm it is to be disrespectful toward them.

Mouzi’s “Disposing of Error” (Lihuo Lun) responds to this question by saying: “The questioner said, “The Classic of Filiality says, ‘Our body, limbs, hair, and skin are all received from our fathers and mothers. We dare not injure them.’ When Zengzi was about to die, he bared his hands and feet [to show he had preserved them intact from all harm, “Analects” 8:3]. But now the monks shave their heads. How this violates the sayings of the sages and is out of keeping with the way of the filial!” Mouzi said... “Confucius has said, ‘There are those with whom one can pursue the Way … but with whom one cannot weigh [decisions].’[“Analects” 9:29]. This is what is meant by doing what is best at the time. Furthermore, the “Classic of Filiality”says, ‘The early kings ruled by surpassing virtue and the essential Way.’ Taibo cut his hair short and tattooed his body, thus following of his own accord the customs of Wu and Yue and going against the spirit of the ‘body, limbs, hair, and skin’ passage. [Uncle of King Wen of Zhou who retired to the barbarian land of Wu and cut his hair and tattooed his body in barbarian fashion, thus yielding his claim to the throne to King Wen.] And yet Confucius praised him, saying that his might well be called the ultimate virtue.”[“Analects” 8:1]

“Why Do Monks Not Marry? “ Another of the great obstacles confronting the early Chinese Buddhist church was clerical celibacy. One of the most important features of indigenous Chinese religion is devotion to ancestors. If there are no descendants to make the offerings, then there will be no sacrifices. To this is added the natural desire for progeny. Traditionally, there could be no greater calamity for a Chinese than childlessness.

Mouzi’s “Disposing of Error” says:“The questioner said, “Now of felicities there is none greater than the continuation of one’s line of unfilial conduct there is none worse than childlessness. The monks forsake wife and children reject property and wealth. Some do not marry all their lives. How opposed this conduct is to felicity and filiality!” Mouzi said … “Wives, children, and property are the luxuries of the world, but simple living and doing nothing (“wuwei”) are the wonders of the Way. Laozi has said, ‘Of reputation and life which is dearer? Of life and property, which is worth more?’ [ “Daodejing”44] … Xu You and Chaofu dwelt in a tree. Boyi and Shuqi starved in Shouyang, but Confucius praised their worth, saying, ‘ [“Analects” 7:14] They sought to act in accordance with humanity and they succeeded in acting so.’ One does not hear of their being ill.spoken of because they were childless and propertyless. The monk practices the Way and substitutes that for the pleasures of disporting himself in the world. He accumulates goodness and wisdom in exchange for the joys of wife and children.”

Mouzi's Disposing of Error on Rebirth and Immortality

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Chinese ancestor worship was premised on the belief that the souls of the deceased, if not fed would suffer. Rationalistic Confucianism, while taking over and canonizing much of Chinese tradition including the ancestral sacrifices, was skeptical about the existence of spirits and an afterlife apart from the continuance of family life. The Buddhists, though denying the existence of an immortal soul, accepted transmigration, and the early Chinese understood this to imply a belief in an individual soul that passed from one body to another until the attainment of enlightenment. The following passage must be understood in light of these conflicting and confusing interpretations. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ]

Mouzi’s “Disposing of Error” addresses this issue by saying: “The questioner said, “The Buddhists say that after a man dies he will be reborn. I do not believe in the truth of these words. …” Mouzi said … ‘The spirit never perishes. Only the body decays. The body is like the roots and leaves of the five grains. When the roots and leaves come forth they inevitably die. But do the seeds and kernels perish? Only the body of one who has achieved the Way perishes.” Someone said, “If one follows the Way one dies. If one does not follow the Way one dies. What difference is there?” Mouzi said, “You are the sort of person who, having had not a single day of goodness, yet seeks a lifetime of fame. If one has the Way, even if one dies, one’s soul goes to an abode of happiness. If one does not have the Way, when one is dead one’s soul suffers misfortune.”

“Does Buddhism Have No Recipe for Immortality? “ Within the movement broadly known as Daoism there were several tendencies, one the quest for immortality, another an attitude of superiority to questions of life and death. The first Chinese who took to Buddhism did so out of a desire to achieve superhuman qualities, among them immortality. The questioner is disappointed to learn that Buddhism does not provide this after all. Mouzi counters by saying that even in Daoism, if properly understood, there is no seeking after immortality.

According to Mouzi’s “Disposing of Error”: “The questioner said, “The Daoists say that Yao, Shun, the Duke of Zhou, and Confucius and his seventy-two disciples did not die, but became immortals. The Buddhists say that men must all die, and that none can escape. What does this mean?” Mouzi said, “Talk of immortality is superstitious and unfounded; it is not the word of the sages. Laozi said, ‘Even Heaven and Earth cannot last forever. How much less can human beings!’ [“Daedejing” 23] Confucius said, ‘The wise man leaves the world, but humaneness and filial piety last forever.’ I have looked into the six arts and examined the commentaries and records. According to them Yao died; Shun had his [place of burial at] Mount Cangwu; Yu has his tomb on Kuaiji; Boyi and Shuqi have their grave in Shouyang. King Wen died before he could chastise [the tyrant] Zhou; King Wu died without waiting for [his son] King Cheng to grow up … And, of Yan Yuan, the Master said, ‘Unfortunately, he was short-lived,’likening him to a bud that never bloomed. All of these things are clearly recorded in the Classics: they are the absolute words of the sages. “I make the Classics and the commentaries my authority and find my proof in the world of men. To speak of immortality, is this not a great error?”

Spread of Buddhism in the Six Dynasties Period (A.D. 220-589)

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “It will be remembered that Buddhism came to China overland and by sea in the Han epoch. The missionary monks who came from abroad with the foreign merchants found little approval among the Chinese gentry. They were regarded as second-rate persons belonging, according to Chinese notions, to an inferior social class. Thus the monks had to turn to the middle and lower classes in China. Among these they found widespread acceptance, not of their profound philosophic ideas, but of their doctrine of the after life. This doctrine was in a certain sense revolutionary: it declared that all the high officials and superiors who treated the people so unjustly and who so exploited them, would in their next reincarnation be born in poor circumstances or into inferior rank and would have to suffer punishment for all their ill deeds. The poor who had to suffer undeserved evils would be born in their next life into high rank and would have a good time. This doctrine brought a ray of light, a promise, to the country people who had suffered so much since the Eastern Han period of the second century A.D. Their situation remained unaltered down to the fourth century; and under their alien rulers the Chinese country population became Buddhist. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The merchants made use of the Buddhist monasteries as banks and warehouses. Thus they, too, were well inclined towards Buddhism and gave money and land for its temples. The temples were able to settle peasants on this land as their tenants. In those times a temple was a more reliable landlord than an individual alien, and the poorer peasants readily became temple tenants; this increased their inclination towards Buddhism.

“Buddhism, quite apart from the special case of "Khotan Buddhism" (described below), underwent extensive modification on its way across Central Asia. Its main Indian form (Hinayana) was a purely individualistic religion of salvation without a God—related in this respect to genuine Taoism—and based on a concept of two classes of people: the monks who could achieve salvation and, secondly, the masses who fed the monks but could not achieve salvation. This religion did not gain a footing in China; only traces of it can be found in some Buddhistic sects in China. Mahayana Buddhism, on the other hand, developed into a true popular religion of salvation. It did not interfere with the indigenous deities and did not discountenance life in human society; it did not recommend Nirvana at once, but placed before it a here-after with all the joys worth striving for. In this form Buddhism was certain of success in Asia. On its way from India to China it divided into countless separate streams, each characterized by a particular book. Every nuance, from profound philosophical treatises to the most superficial little tracts written for the simplest of souls, and even a good deal of Turkestan shamanism and Tibetan belief in magic, found their way into Buddhist writings, so that some Buddhist monks practiced Central Asian Shamanism.

“In spite of Buddhism, the old religion of the peasants retained its vitality. Local diviners, Chinese shamans (wu), sorcerers, continued their practices, although from now on they sometimes used Buddhist phraseology. Often, this popular religion is called "Taoism ", because a systematization of the popular pantheon was attempted, and Lao Tzu and other Taoists played a role in this pantheon. Philosophic Taoism continued in this time, aside from the church-Taoism of Chang Ling and, naturally, all kinds of contacts between these three currents occurred. The Chinese state cult, the cult of Heaven saturated with Confucianism, was another living form of religion. The alien rulers, in turn, had brought their own mixture of worship of Heaven and shamanism. Their worship of Heaven was their official "representative" religion; their shamanism the private religion of the individual in his daily life. The alien rulers, accordingly, showed interest in the Chinese shamans as well as in the shamanistic aspects of Mahayana Buddhism. Not infrequently competitions were arranged by the rulers between priests of the different religious systems, and the rulers often competed for the possession of monks who were particularly skilled in magic or soothsaying.

Yencheng, on the Yellow Sea in n northeastern Jiangsu province, was a center of Buddhism in the A.D. 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th centuries with the kingdom there reaching its peak during Eastern Wei and Northern Qi (A.D. 550-577) Dynasties, when the commission of statues and art works was a common practice among wealthy families. There were some attacks on the religion. During an anti-Buddhist campaign launched in A.D. 446 monks were killed, sculptures were destroyed. In A.D. 574, monks were ordered to abandon their temples, in A.D. 841 during the Tang Dynasty, emperor Wuzong ordered the destruction of numerous Buddhist temples. [Source: Larry Hilgers, Archaeology, September 2012]

Spread of Buddhism to Tibetans and Mongol-Like Tribes in the 4th-6th Centuries

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The Indian, Sogdian, and Turkestani monks were readily allowed to settle by the alien rulers of China, who had no national prejudice against other aliens. The monks were educated men and brought some useful knowledge from abroad. Educated Chinese were scarcely to be found, for the gentry retired to their estates, which they protected as well as they could from their alien ruler. So long as the gentry had no prospect of regaining control of the threads of political life that extended throughout China, they were not prepared to provide a class of officials and scholars for the anti-Confucian foreigners, who showed interest only in fighting and trading. Thus educated persons were needed at the courts of the alien rulers, and Buddhists were therefore engaged. These foreign Buddhists had all the important Buddhist writings translated into Chinese, and so made use of their influence at court for religious propaganda. This does not mean that every text was translated from Indian languages; especially in the later period many works appeared which came not from India but from Sogdia or Turkestan, or had even been written in China by Sogdians or other natives of Turkestan, and were then translated into Chinese. In Turkestan, Khotan in particular became a centre of Buddhist culture. Buddhism was influenced by vestiges of indigenous cults, so that Khotan developed a special religious atmosphere of its own; deities were honoured there (for instance, the king of Heaven of the northerners) to whom little regard was paid elsewhere. This "Khotan Buddhism" had special influence on the Buddhist Turkish peoples.

“Big translation bureaux were set up for the preparation of these translations into Chinese, in which many copyists simultaneously took down from dictation a translation made by a "master" with the aid of a few native helpers. The translations were not literal, but were paraphrases, most of them greatly reduced in length, glosses were introduced when the translator thought fit for political or doctrinal reasons, or when he thought that in this way he could better adapt the texts to Chinese feeling.

The Toba, together with many Chinese living in the Toba empire, were all captured by Buddhism, and especially by its shamanist element. One element in their preference of Buddhism was certainly the fact that Buddhism accepted all foreigners alike—both the Toba and the Chinese were "foreign" converts to an essentially Indian religion; whereas the Confucianist Chinese always made the non-Chinese feel that in spite of all their attempts they were still "barbarians" and that only real Chinese could be real Confucianists. Secondly, it can be assumed that the Toba rulers by fostering Buddhism intended to break the power of the Chinese gentry. A few centuries later, Buddhism was accepted by the Tibetan kings to break the power of the native nobility. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“Throughout the early period of Buddhism in the Far East, the question had been discussed what should be the relations between the Buddhist monks and the emperor, whether they were subject to him or not. This was connected, of course, with the fact that to the early fourth century the Buddhist monks were foreigners who, in the view prevalent in the Far East, owed only a limited allegiance to the ruler of the land. The Buddhist monks at the Toba court now submitted to the emperor, regarding him as a reincarnation of Buddha. Thus the emperor became protector of Buddhism and a sort of god. This combination was a good substitute for the old Chinese theory that the emperor was the Son of Heaven; it increased the prestige and the splendour of the dynasty. At the same time the old shamanism was legitimized under a Buddhist reinterpretation. Thus Buddhism became a sort of official religion. The emperor appointed a Buddhist monk as head of the Buddhist state church, and through this "Pope" he conveyed endowments on a large scale to the church. T'an-yao, head of the state church since 460, induced the state to attach state slaves, i.e. enslaved family members of criminals, and their families to state temples. They were supposed to work on temple land and to produce for the upkeep of the temples and monasteries. Thus, the institution of "temple slaves" was created, an institution which existed in South Asia and Burma for a long time, and which greatly strengthened the economic position of Buddhism.

“Like all Turkish peoples, the Toba possessed a myth according to which their ancestors came into the world from a sacred grotto. The Buddhists took advantage of this conception to construct, with money from the emperor, the vast and famous cave-temple of Yun-kang, in northern Shanxi. If we come from the bare plains into the green river valley, we may see to this day hundreds of caves cut out of the steep cliffs of the river bank. Here monks lived in their cells, worshipping the deities of whom they had thousands of busts and reliefs sculptured in stone, some of more than life-size, some diminutive. The majestic impression made today by the figures does not correspond to their original effect, for they were covered with a layer of coloured stucco.

“We know only few names of the artists and craftsmen who made these objects. Probably some at least were foreigners from Turkestan, for in spite of the predominantly Chinese character of these sculptures, some of them are reminiscent of works in Turkestan and even in the Near East. In the past the influences of the Near East on the Far East—influences traced back in the last resort to Greece—were greatly exaggerated; it was believed that Greek art, carried through Alexander's campaign as far as the present Afghanistan, degenerated there in the hands of Indian imitators (the so-called Gandhara art) and ultimately passed on in more and more distorted forms through Turkestan to China. Actually, however, some eight hundred years lay between Alexander's campaign and the Toba period sculptures at Yun-kang and, owing to the different cultural development, the contents of the Greek and the Toba-period art were entirely different. We may say, therefore, that suggestions came from the centre of the Greco-Bactrian culture (in the present Afghanistan) and were worked out by the Toba artists; old forms were filled with a new content, and the elements in the reliefs of Yun-kang that seem to us to be non-Chinese were the result of this synthesis of Western inspiration and Turkish initiative. It is interesting to observe that all steppe rulers showed special interest in sculpture and, as a rule, in architecture; after the Toba period, sculpture flourished in China in the Tang period, the period of strong cultural influence from Turkish peoples, and there was a further advance of sculpture and of the cave-dwellers' worship in the period of the "Five Dynasties" (906-960; three of these dynasties were Turkish) and in the Mongol period.

“But not all Buddhists joined the "Church", just as not all Taoists had joined the Church of Chang Ling's Taoism. Some Buddhists remained in the small towns and villages and suffered oppression from the central Church. These village Buddhist monks soon became instigators of a considerable series of attempts at revolution. Their Buddhism was of the so-called "Maitreya school", which promised the appearance on earth of a new Buddha who would do away with all suffering and introduce a Golden Age. The Chinese peasantry, exploited by the gentry, came to the support of these monks whose Messianism gave the poor a hope in this world. The nomad tribes also, abandoned by their nobles in the capital and wandering in poverty with their now worthless herds, joined these monks. We know of many revolts of Hun and Toba tribes in this period, revolts that had a religious appearance but in reality were simply the result of the extreme impoverishment of these remaining tribes.

“In addition to these conflicts between state and popular Buddhism, clashes between Buddhists and representatives of organized Taoism occurred. Such fights, however, reflected more the power struggle between cliques than between religious groups. The most famous incident was the action against the Buddhists in 446 which brought destruction to many temples and monasteries and death to many monks. Here, a mighty Chinese gentry faction under the leadership of the Ts'ui family had united with the Taoist leader K'ou Ch'ien-chih against another faction under the leadership of the crown prince.

“With the growing influence of the Chinese gentry, however, Confucianism gained ground again, until with the transfer of the capital to Loyang it gained a complete victory, taking the place of Buddhism and becoming once more as in the past the official religion of the state. This process shows us once more how closely the social order of the gentry was associated with Confucianism.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021