BUDDHISM IN CHINA

5th century Bodhisattva from Yungang China is the world’s biggest Buddhist nation. Buddhism was first introduced into China in the first century A.D. from India. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Buddhism originated from India, and was founded by the Buddha Sakyamuni (ca. 565-486 B.C.) in the sixth century B.C. When it was first introduced into China during the Han dynasty, its teachings collided with China's cultural traditions. However, through continuous learning and integration on both sides, the main customs, practices, and beliefs of Buddhism, such as the six samara and karma, became deeply ingrained into the minds of the Chinese people and incorporated into their culture and traditions.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Buddhism is similar to Taoism in its rejection of striving and material goods but differs from traditional Chinese beliefs in other ways. The goal of Buddhism is nirvana, a transcendence of the mind and body. Mahayana (Great Vehicle) Buddhism predominates in China as well as Japan and Korea. It is different from Theravada Buddhism — sometime pejoratively called Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) — which predominates in Southeast Asia. Among Tibetan peoples, Tibetan Buddhism — a branch of Vajrayana, or Tantric, or Esoteric Buddhism — is practiced. It is considered a kind of Mahayana Buddhism but is distinguished by its emphasis on tantras ( mystical or magical texts or practices).

By the Tang era, beginning in the 7th century, Buddhism was firmly established as one of the primary religions of China. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Chinese Buddhist monks went on to develop some of the most sophisticated Mahayanist philosophies, some of which spread to Japan and Korea as well. Mahayana Buddhism combines the original Buddhist goals of realization of the transitoriness of material existence with a posited cosmology of myriad Buddhas and bodhisattvas (Buddhas-to-be) who are potential helpers of those who believe. The Buddhist tradition in China thus afforded its adherents everything from a sophisticated system of philosophy and psychology, to the opportunity for monastic meditative practice toward the goal of relief from existence, to help from Buddhist divinities enshrined in local temples. Over the last thousand years, many Buddhist and Daoist divinities, beliefs, and practices were absorbed into the folk religion, so that bodhisattvas function as local gods, for example, and Buddhist monks are as likely as Daoist priests to perform funerals, exorcisms, and other rites for the common people. [Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Buddhism in China has gone through cycles of rising, flourishing and declining. Over the centuries it has been shaped by the tensions between the Indian-influenced traditions and Chinese traditions. In the eyes of many scholars the tension is what kept Buddhism alive and relevant. When the tensions waned so too did the religion. At its peak Buddhism had hundreds of millions of followers and deeply shaped Chinese culture and thought.

Buddhism entered China mostly in the Mahayana form as it was going through many changes in India. Each major change resulted in a new school in China. Chinese Buddhism evolved through the study of sutras in Chinese. Doctrinal issues were addressed using different sutras than those used in India. The various schools tended to differ from each other and from those in India based on the sutras they emphasized as being truest. When Buddhism reemerged after the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) it was simpler and more influenced by the West. While Tibetan Buddhism encourages lamas to counsel students individually, Chinese Buddhism puts more emphasis on teaching monks in groups in monasteries.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism in China Buddhist Studies buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in China Wikipedia Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ;

Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ;

East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; Mahayana Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Comparison of Buddhist Traditions (Mahayana – Therevada – Tibetan) studybuddhism.com ;

The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: complete text and analysis nirvanasutra.net ;

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Mahayana Buddhism cttbusa.org ; Chinese Religion and Philosophy: Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; LOTUS SUTRA AND THE DEFENSE OF BUDDHISM AGAINST CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com; CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES, MONKS AND FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHISM TODAY factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM VERSUS THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN THE TANG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; FAXIAN AND HIS JOURNEY IN CHINA AND CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com; XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey” by Kenneth Ch'en Amazon.com; “Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China” by Christine Mollier Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; “China Root: Taoism, Ch'an, and Original Zen” by David Hinton Amazon.com; Buddhism Between Tibet and China” Matthew Kapstein Amazon.com; “The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang” by Sally Hovey Wriggins Amazon.com; “Xuanzang: China's Legendary Pilgrim and Translator”by Benjamin Brose Amazon.com; “Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Faxian and James Legge Amazon.com; Schools of Buddhism in China: “Chan Buddhism” by Peter D. Hershock Amazon.com; “The Essence of Chan: A Guide to Life and Practice according to the Teachings of Bodhidharma” by Guo Gu (Author) Amazon.com; “Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice” by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com; Famous Sutras: “The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic” by Gene Reeves Amazon.com; “The Lotus Sutra” by Burton Watson Amazon.com; “The Diamond Sutra” by Red Pine Amazon.com; Buddhist Art: “The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com; “Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road” by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al. Amazon.com; “Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road” by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com

Buddhists in China

Xuanzang, the Chinese monk who traveled extensively in India

Buddhism is regarded as the largest religion in China today, with 100 million followers, or about 8 percent of the Chinese population, including Tibetans, Mongolians and a few other ethnic minorities like the Dai. There is roughly around the same number of Christians and Muslims. Still, it can be argued that Buddhism is not embraced with the same enthusiasm and devotion as it is in other Asian countries and in Tibet. Many Buddhist temples in China are watched over by caretakers not monks. In Japan and Korea, many people are buried according to Buddhist rites, but that is not usually the case in China.

According to the official website of the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA) of China, there are currently 33,652 Buddhist temples and monasteries in China, of which 3,853 are Tibetan Buddhist. According to SARA most of the Tibetan Buddhist venues are in Tibet and bordering areas (46 percent of them, or 1,779 venues, are in Tibet autonomous region and 27.4 percent, or 783 venues, are in Sichuan province). [Source: Xu Wei, China Daily, December 19, 2015; [Source: Kou Jie, Global Times January 18, 2016]

In 2005 the Chinese government acknowledged that there were an estimated 100 million adherents to various sects of Buddhism and some 16,000 temples 9,500 and monasteries, many maintained as cultural landmarks and tourist attractions. The Buddhist Association of China was established in 1953 to oversee officially sanctioned Buddhist activities. According to SARA there were about 13,000 Buddhist temples and about 200,000 Buddhist monks and nuns in the 1990s. [Source: Library of Congress]

Buddhism as a Religion Imported to and Exported from China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Buddhism is an interesting form of Chinese religion for many reasons, not least because it was the first major religious tradition in China that was “imported” from abroad. (Other forms of Buddhism from Tibet and Mongolia, Christianity in different guises, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Islam would follow later.) Long after Buddhism had become a natural part of the Chinese religious landscape, many Chinese — Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike — still pondered the significance of the foreign origin of the religion. [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

China was the only Buddhist country that possessed a civilization before the introduction of Buddhism. For over a thousand years Buddhism dominated religious life in China, having both a profound impact on China and Buddhism and producing a great body of literature and art. China was the conduit through which Buddhism reached Korea, Japan and Vietnam. The Buddhism found in China is almost exclusively Mahayana.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “, Buddhism is an Indian system of thought that was transmitted to China by Central Asian traders and Buddhist monks as early as the first century A.D. Later it passed into Korea by the fourth century and Japan by the sixth. Its influence on all three cultures was enormous... Buddhism, in its long history, branched into many competing philosophical schools, religious traditions, and monastic sects. There are literally dozens of very different versions of Buddhism in East Asian history and in the world today (although, oddly, Buddhism died out in its native India at a rather early date). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/]

Within China, Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Regional variation in the material trappings of Buddhism should be kept in mind. The biggest divide is between areas where Tibetan Buddhism is dominant (Tibet, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia predominantly), and other regions of China. Buddhism arrived in Tibet by a different route, primarily from India, and although there was much interchange between Tibetan Buddhism and schools of Buddhism in Tang and later China, many differences in both doctrine and practice have persisted until today. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Four Noble Truths

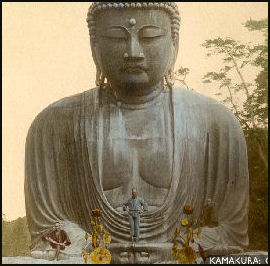

Great Buddha of Kamakura, in Japan

Buddhism was introduced to Japan via China Dr. Eno University wrote: “The Buddha's most basic insight was consistent with the personal crisis that had led him into the forest: life, which at times seems so full of good things, is actually a process of endless suffering. Even if we are not actually hungry or in pain, even if we live in sumptuous luxury, we actually endure ceaseless emotional hunger and pain. The reason why is that we are creatures of wants: our longings for things or people that will please us and satisfy our needs. The Buddha, through the vision of meditative trance, had become convinced that the world of things is actually illusory, that the beauties of the world are mere mirages that we project upon a meaningless universe of dust. We long for these illusory things, and knowingly or unknowingly, we live our lives enduring the fact that what we long for must always, in the end, elude our grasp. /+/

“Thus, for Buddha, all life is suffering..and the story gets worse! The Buddha adopted from his Hindu religious environment the doctrine of “samsara”, the belief that all existence is an endless cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Therefore, when the Buddha tells us that we must endure nothing but suffering all our lives, he is not speaking of decades of unhappiness; suffering is forever. In the Buddhist picture, life is not much different from hell, except the flames are missing, so it's easy to mistake where you are. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Buddha preached this picture of life in a formula known as the Four Noble Truths, the most basic doctrine of Buddhism. These truths tell us, 1) that life in “samsara”is suffering; 2) that this has a cause..our longing for illusory things; 3) that this suffering may be ended by following the path of the Buddha; 4) what that path is. The first two truths comprise the basic worldview of Buddhist thought. The final two truths point towards the practical core of Buddhism: its path towards salvation through self-cultivation in the manner of the Buddha's own struggle to enlightenment.” /+/

Philosophical and Religious Aspects of Buddhism

Buddha in a dragon boat, from Kizil Caves in western China

Dr. Eno wrote: “ Most of us who first hear the Four Noble Truths have an initially negative response. Not only do the first two paint an unrelievedly depressing picture of life, but they do not seem to most of us true. After all, life has many obvious pleasures: food, love, music, cable. Why focus solely on the bad side? Furthermore, it is not at all clear that the Buddha was strictly correct about the illusory nature of things. For example, many people have strong convictions about the real existence of tables and chairs. It is not certain how the historical Buddha responded to audiences who may have raised these objections. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“However, one of the principal activities of those who did choose to heed the Buddha's message and follow his teachings was the elaboration of a rich and sophisticated set of philosophical arguments that were designed to demonstrate the coherence of the Buddha's claims about the nature of the world. These arguments form the basis of Buddhist philosophy, which includes distinctive doctrines of metaphysics (theory of the basic structures of reality), psychology, ethics, and logic. Although some of Buddha's early audiences surely doubted his words, others were inclined to adopt his portrait of life as suffering. The poor and the sick would more easily see a message such as Buddha's as one of hope rather than despair, and Hindu yogins who had withdrawn from society would have seen in the Buddha's picture of an illusory world confirmation of their own decisions. For such people, the last two Noble Truths represented a path to salvation, albeit a very difficult path, involving years of self-denial and rigorous meditational training. /+/

“But the Buddha's own picture of salvation seems to have been so bare that few others would have found it enticing. For the Buddha, the ultimate goal of any conscious being was simply release from “samsara”and the cessation of suffering..and that was it! No afterlife, no paradise, no talk with Elvis. Nothing. In fact, “nothing” was the only description offered of the state of permanent release from “samsara”: the state of “nirvana”. “Nirvana”was simply no longer being. For those who do not share the Buddhist belief in reincarnation, “nirvana”looks very much like death. /+/

“While all of us have bad days, few would respond by undertaking years of rigorous self-denial leading to personal extinction. Therefore, those who followed the Buddha realized early on that to enlarge the audience of their faith it would be necessary to make the path easier for most to travel and the end goal more attractive. These Buddhist disciples gradually built up a very large corpus of sacred texts and devotional practices that added to Buddhism inspirational religious features. self-cultivation came to involve more than meditation.-one could approach “nirvana”now through doing good works, chanting holy scripture, praying to scores of Buddhist saints, and contributing tax-free gifts to Buddhist monasteries. And “nirvana”too was gradually redesigned into a sort of super.physical space in which the souls of perfected people enjoyed the company of the gods and saints for eternity, in surroundings as comfortable and gemlike as the palace from which Siddhartha Gautama had once fled.* Through the development of a philosophical core that could defend the very counter-intuitive claims that the Buddha made about reality, and the development of a religious tradition that greatly enhanced the attractiveness of Buddhism's salvational message, Buddhism supplied itself with tools that enabled it to emerge from India and sweep over all of East Asia, becoming a dominant religious tradition there for over a thousand years. /+/

“* These ideas were not without problems. Buddhist philosophy is very firm in rejecting the existence of the soul or any enduring principle of personal identity in life or in “nirvana”. But the philosophical and religious aspects of Buddhism, like two spouses, learned to live together without worrying overmuch about perfect consistency. /+/

Fojiao: The Teaching of the Buddha in China

Baoen sutra paradise

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The very name given to Buddhism in China offers important clues about the way that the tradition has come to be defined in China. Buddhism is often called Fojiao, literally meaning “the teaching (jiao) of the Buddha (Fo).” Buddhism thus appears to be a member of the same class as Confucianism and Daoism: the three teachings are Rujiao (“teaching of the scholars” or Confucianism); Daojiao (“teaching of the Dao” or Daoism); and Fojiao (“teaching of the Buddha” or Buddhism). [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

“But there is an interesting difference here, one that requires close attention to language. As semantic units in Chinese, the words Ru and Dao work differently than does Fo. The word Ru refers to a group of people and the word Dao refers to a concept, but the word Fo does not make literal sense in Chinese. Instead it represents a sound, a word with no semantic value that in the ancient language was pronounced as “bud,” like the beginning of the Sanskrit word “buddha.”

“The meaning of the Chinese term (Fo) derives from the fact that it refers to a foreign sound. [In fact the linguistic situation is more complex. Some scholars suggest that Fo is a transliteration not from Sanskrit but from Tocharian; see, for instance, Ji Xianlin, “Futu yu Fo,” Guoli zhongyang yanjiuyuan Lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan 20.1 (1948): 93-105.] In Sanskrit the word “buddha” means “one who has achieved enlightenment,” one who has “awakened” to the true nature of human existence. Rather than using any of the Chinese words that mean “enlightened one,” Buddhists in China have chosen to use a foreign word to name their teaching, much as native speakers of English refer to the religion that began in India not as “the religion of the enlightened one,” but rather as “Buddhism,” often without knowing precisely what the word “Buddha” means. Thus, referring to Buddhism in China as Fojiao involves the recognition that this teaching, unlike the other two, originated in a foreign land. Its strangeness, its non-native origin, its power are all bound up in its name.

“First of all, although the historical Buddha was believed to have been a prince, thus placing him high on the scale of social respectability, in Chinese eyes he was, ultimately, a foreigner. His doctrine was preached using words that, to the Chinese ear, sounded foreign. The Buddha’s teachings were part and parcel of the early Indian worldview, which often differed from the early Chinese cosmology. And Buddhism brought to China a new form of social organization that stood at odds with the traditional Chinese social structure: the institution of a celibate priesthood (Buddhist monks and nuns) supported by a lay community.

“Many of these differences between Indian and Chinese cultures can be magnified in theory, and one can construct an ahistorical picture of radical difference between two imaginary, monolithic cultures represented by early Indian Buddhism and Chinese religion. It is important to question these handy but misleading stereotypes — which were sometimes used by a minority of anti-Buddhist critics in China. Most Buddhists in China had no independent access to Indian Buddhism, and the Buddhism they learned was already fully consistent with the rest of their social and religious world. The history of Chinese Buddhism consists of the interpretation and reinterpretation of the many strands of religious conception — some native to China and some translated from Indian texts — available to Chinese Buddhists.

India-Based Buddhism Articulated for a Chinese Audience

Brahmin in an 8th century cave painting in Bezeklik

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The propositions of Buddhism were articulated originally in the context of traditional Indian cosmology in the first several centuries B.C., and as Buddhism began to trickle haphazardly into China in the first centuries of the common era (CE), Buddhist teachers were faced with a dilemma. To make their teachings about the Buddha understood to a non-Indian audience, Buddhist teachers often began by explaining the understanding of human existence — the problem, as it were — to which Buddhism provided the answer. [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ]

“The Cycle of Existence: The wisdom to which buddhas awaken is to see that this cycle of existence (samsara in Sanskrit, comprising birth, death, and rebirth) is marked by 1) impermanence — because all things, whether physical objects, psychological states, or philosophical ideas, undergo change; they are brought into existence by preceding conditions at a particular point in time, and they eventually will become extinct. 2) unsatisfactoriness — in the sense that not only do sentient beings experience physical pain, they also face continual disappointment when the people and things they wish to maintain invariably change; and 3) lack of a permanent self (or “no self”), which has a long and complicated history of exegesis in Buddhism. In China the idea of “no-self” (Sanskrit: anatman) was often placed in creative tension with the concept of repeated rebirth

“This unique being was called Gautama (family name) Siddhartha (personal name) during his lifetime, and later tradition refers to him with a variety of names, including Sakyamuni (literally “Sage of the Sakya clan”) and Tathagata (“Thus-Come One”). Followers living after his death lack direct access to him because, as the word “extinction” implies, his release was permanent and complete. His influence can be felt, though, through his traces — through gods who encountered him and are still alive, through long-lived disciples, through the places he touched that can be visited by pilgrims, and through his physical remains and the shrines (stupa) erected over them.

The second understanding a buddha is a generic label for any enlightened being, of whom Sakyamuni was simply one among many. Other buddhas preceded Sakyamuni’s appearance in the world, and others will follow him, notably Maitreya (Chinese: Mile), who is thought to reside now in a heavenly realm close to the surface of the Earth. Buddhas are also dispersed over space: they exist in all directions, and one in particular, Amitayus (or Amitabha, Chinese: Emituo), presides over a land of happiness in the West.

“Bodhisattvas. Related to this second genre of buddha is another kind of figure, a bodhisattva (literally “one who is intent on enlightenment,” Chinese: pusa). Bodhisattvas are found in most forms of Buddhism, but their role was particularly emphasized in the many traditions claiming the polemical title of Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle,” in opposition to Hinayana, “Smaller Vehicle”) that began to develop in the first century B.C. Technically speaking, bodhisattvas are not as advanced as buddhas on the path to enlightenment. While buddhas appear to some followers as remote and all-powerful, bodhisattvas often serve as mediating figures whose compassionate involvement in the impurities of this world makes them more approachable. Like buddhas in the second sense of any enlightened being, bodhisattvas function both as models for followers to emulate and as saviors who intervene actively in the lives of their devotees. Bodhisattvas particularly popular in China include Avalokitesvara (Chinese: Guanyin, Guanshiyin, or Guanzizai); Bhaisajyaguru (Chinese: Yaoshiwang); Ksitigarbha (Chinese: Dizang); Mañjusri (Chinese: Wenshu); and Samantabhadra (Chinese: Puxian).

Three Jewels — Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha- in Chinese Terms

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In addition to the word “Buddhism” (Fojiao), Chinese Buddhists have represented the tradition by the formulation of the “three jewels” (Sanskrit: triratna, Chinese: sanbao). Coined in India, the three terms carried both a traditional sense as well as a more worldly reference that is clear in Chinese sources. [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ; On the extended meaning of the three jewels in Chinese sources, see Jacques Gernet, Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries, trans. Franciscus Verellen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p. 67.]

Tang-era painting Doctrine Under a Tree

“The first jewel is buddha, the traditional meaning of which has been discussed above. In China the term refers not only to enlightened beings, but also to the materials through which buddhas are made present, including statues, the buildings that house statues, relics and their containers, and all the finances needed to build and sustain devotion to buddha images.

“The second jewel is the dharma (Chinese: fa), meaning “truth” or “law.” The dharma includes the doctrines taught by the Buddha and passed down in oral and written form, thought to be equivalent to the universal cosmic law. Many of these teachings are expressed in numerical form, like the three marks of existence (impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and no-self, discussed above); the four noble truths (unsatisfactoriness, cause, cessation, path); and so on.

“As a literary tradition the dharma also comprises many different genres, the most important of which is called sutra in Sanskrit.(3) Sutras usually begin with the words “Thus have I heard. Once, when the Buddha dwelled at... ” That phrase is attributed to the Buddha’s closest disciple, Ananda, who according to tradition was able to recite all of the Buddha’s sermons from memory at the first convocation of monks held after the Buddha died. In its material sense the dharma referred to all media for the Buddha’s law in China, including sermons and the platforms on which sermons were delivered, Buddhist rituals that included preaching, and the thousands of books — first handwritten scrolls, then booklets printed with wooden blocks — in which the truth was inscribed. (3) The Sanskrit word refers to the warp thread of a piece of cloth, the regulating or primary part of the doctrine (compare its Proto-Indo-European root, *syu, which appears in the English words suture, sew, and seam). The earliest Chinese translators of Buddhist Sanskrit texts chose a related loaded term to render the idea in Chinese: jing, which denotes the warp threads in the same manner as the Sanskrit, but which also has the virtue of being the generic name given to the classics of the Confucian and Daoist traditions.,

“The third jewel is sangha (Chinese: sengqie or zhong), meaning “assembly.” Some sources offer a broad interpretation of the term, which comprises the four sub-orders of 1) monks; 2) nuns; 3) lay men; and 4) lay women. Other sources use the term in a stricter sense to include only monks and nuns, that is, those who have left home, renounced family life, accepted vows of celibacy, and undertaken other austerities to devote themselves full-time to the practice of religion.

“The differences and interdependencies between householders and monastics were rarely absent in any Buddhist civilization. In China those differences found expression in both the spiritual powers popularly attributed to monks and nuns and the hostility sometimes voiced toward their way of life, which seemed to threaten the core values of the Chinese family system. The interdependent nature of the relationship between lay people and the professionally religious is seen in such phenomena as the use of kinship terminology — an attempt to re-create family — among monks and nuns and the collaboration between lay donors and monastic officiants in a wide range of rituals designed to bring comfort to the ancestors.

““Sangha” in China also referred to all of the phenomena considered to belong to the Buddhist establishment. Everything and everyone needed to sustain monastic life, in a very concrete sense, was included: the living quarters of monks; the lands deeded to temples for occupancy and profit; the tenant families and slaves who worked on the farm land and served the sangha; and even the animals attached to the monastery farms.

Chinese Buddhist Deities

In Mayahana Buddhism: Besides Sakyamuni Buddha (historical Buddha), other contemporary buddhas like Amitabha and Medicine Buddha are also very popular. Important Buddha images in Chinese Buddhism include the 1) Sakyamuni Buddha, associated with the Tien-tai and Ch’an sects and the Saddharmapundarika sutra, the most popular sutra in China; 2) Amitabha Buddha (Amit’o, Buddha of the Western Paradise), associated with the Pure Land sect; 3) Maitreya (Milo), the Future Buddha; 4) Bhaisajyaguro Buddha (Yao-shih), “The Master of Healing," who presides over the Eastern Paradise and us often sought by worshipers with troubles.

Bodhisattvas particularly popular in China include Avalokitesvara (Chinese: Guanyin, Guanshiyin, or Guanzizai); Bhaisajyaguru (Chinese: Yaoshiwang); Ksitigarbha (Chinese: Dizang); Mañjusri (Chinese: Wenshu); and Samantabhadra (Chinese: Puxian). [Source: “Buddhism: The ‘Imported’ Tradition” from the “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ]

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva (Guanyin, Kuan-yin) possesses the power to help all those suffering from a number of troubles including fire, poison and wild beasts. Kshitigarbha Bodhisattva (Ti-sang) specializes in rescuing beings from hell. Chinese Buddhist seek help from these Bodhisattvas as well as the Buddhas Tao-shih and Amit’o in personal matters.

Guanyin (Kuan-yin)

bth century Wall painting of Guanyin

Guanyin (Kuanyin), the Goddess of Mercy, is arguably the most popular deity in China. Found in Buddhist and Taoist temples and on family altars at home but regarded as a Buddhist goddess, she is associated with both purity and compassion and has traditionally been sought by expectant mother for help with child birth. Often depicted with multiple heads and arms, she is closely linked with Avalokitesvara, the eleven-headed and the multi-armed Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. Guanyin is usually represented sitting on a lotus blossom. The lotus symbolizes purity because it grows from dirty water without getting dirty. Some say Guanyin was originally the God of Mercy. He became the Goddess of Mercy after the introduction of Christianity to China as an answer to the Virgin Mary. Others say Guanyin was a real person who lived in southwestern China around 300 B.C. and was killed by her father because she refused to marry the man he wanted her to marry. According to legend, after she died she transformed hell into paradise and was permitted by the God of the Underworld to return to earth. During her nine year stay on earth she performed many deeds and miracles, including saving her father.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Kuan-yin (Sanskrit: Avalokitesvara), also known as Kuan-shih-yin ("Beholder of All Sounds") or Kuan-tzu-tsai ("Sovereign Beholder") represents the Bodhisattva of the Ten Stages in Mahayana Buddhism. The belief in Kuan-yin originated in India and entered China and spread rapidly after the third century and divided into the three forms of Sutrayana, Tantrayana, and Sinified. The image of Kuan-yin in the "Universal Gate Chapter of the Kuan-yin Bodhisattva" in The (Sublime Dharma of the) Lotus Sutra in the National Palace Museum collection belongs to the Sutrayana system. The Kuan-yin Sutra represents a classic example of the Tantrayana type, its Kuan-yin image belonging to the esoteric Kuan-yin form. The sinification of Kuan-yin belief was much influenced by popular literature, giving rise to various forms with incarnations having as many as 32 or 33 heads. To this day, many temples and monasteries are dedicated to Kuan-yin throughout the country. Known as the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, countless numbers of followers have called upon this deity for salvation and intervention. Kuan-yin thus has become one of the most well known bodhisattvas in the Mahayana (popular) sect of Buddhism. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The first translation into Chinese of the "Lotus Sutra," which contains a chapter devoted to Kuan-yin, was completed in 286 by Dharmaraksa, marking the introduction of this deity to China. Over the following 1700 years, learned monks have translated more than eighty scriptures associated with Kuan-yin. To further propagate the belief in this deity in China, non-orthodox scriptures based on Buddhist canons (sutras) have been written, countless collections of miracle tales have been compiled, and many stories and legends have been spread. Through the slow yet steady process of sinification, the male form of Kuan-yin as originally seen in Indian art gave way to the female one of motherly compassion. Popularly known as the Goddess of Mercy, Kuan-yin evolved from foreign origins to become an integral part of Chinese culture. \=/

Types of Kuan-yin in China

Guanyin of a Thousand arms and eyes

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In China, the belief in Kuan-yin is varied and complex. Overall, however, three types may be observed; the exoteric ("general"), esoteric ("secret"), and sinified (Chinese) types of Kuan-yin. The images associated with these types also differ accordingly. The exoteric Kuan-yin type is based on the general sutras of Mahayana Buddhism, such as The Kuan-yin Chapter of the "Lotus Sutra," the "Avatamsaka Sutra," and the "Amitabha Sukhavativyuha" This Kuan-yin has a single head and two arms, wears a crown adorned with a Buddha, and often holds such objects as a lotus blossom, a willow branch, a water vase, rosary beads, or a water cup. To this day, many temples and monasteries are dedicated to Kuan-yin throughout the country. Known as the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, countless numbers of followers have called upon this deity for salvation and intervention. Kuan-yin thus has become one of the most well known bodhisattvas in the Mahayana (popular) sect of Buddhism. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The esoteric Kuan-yin type is based on such esoteric Buddhist canons as "Sutra of the Eleven-headed Kuan-yin," "Sutra of the Thousand-armed Kuan-yin of Great Compassion," and the "Cundi Sutra." This Kuan-yin either has one head and many hands or many heads and many hands, which are often shown holding ritual objects of various kinds to relieve suffering and provide salvation. Examples in this exhibition include "Kuan-yin of Great Compassion" attributed to Fan Ch'iung and "Cundi" by a Ming artist. The sinified form of Kuan-yin is based on Chinese texts, miracle tales, pao-chuan ("precious scrolls" folk literature), and native stories and legends. \=/

“The image of this Kuan-yin form was strongly influenced by popular fiction and includes such varieties as the White-robed Kuan-yin, Kuan-yin Bestowing Children, Kuan-yin of the Fish Basket, and the South Sea Kuan-yin. Furthermore, in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), it was popularly believed that Kuan-yin (according to descriptions in The 25 Great Ones from the "Surangama Sutra" and The Kuan-yin Chapter from the "Lotus Sutra") could transform at will and appear in more than thirty human forms to expound the Buddhist faith. At the time, compilations of 32 and 33 forms of Kuan-yin images were collected to create the 32 Manifestations of Kuan-yin and the 33 Manifestations of Kuan-yin. Most of these images are not found in orthodox sutras and thus reflect one of the most concrete expressions of the sinification of Kuan-yin. \=/

Chinese Buddhist Texts and Printing

The Mahayana Buddhist Canon consists of Tripitaka of disciplines, discourses (sutras) and dharma analysis. It is usually organised in 12 divisions of topics like Cause and Conditions and Verses. It contains virtually all the Theravada Tipikata and many sutras that the latter does not have. The Mayahana Buddhist canon is translated into the local language (except for the five untranslatables), e.g. Tibetan, Chinese and Japanese. Original language of transmission is Sanskrit. ^|^ [Source: Tan Swee Eng, buddhanet.net ^|^]

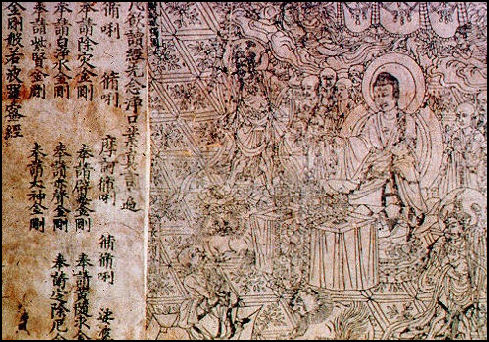

The Chinese Tripitaka contains both Indian writing and Chinese contributions. Each school selects two or three sutras as its basic authority. Versions vary often based on the decisions of editors rather than religious councils. The entire Tripitaka is a massive. An effort to print the entire thing in 980 required 130,000 printing blocks. A modern version published in Japan in the 1920s is comprised of 55 volumes. They largest sections are Mahayana sutras and Chinese commentaries on them.

Buddhist monasteries were instrumental in the development of the world's first block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe that a person can earn merit by duplicating images of Buddha and sacred Buddhist texts. The more images and texts one makes the more merit one earns. Small wooden stamps — the most primitive form of printing — as well as rubbings from stones, seals, and stencils were used to make images over and over. In this way printing developed because it was "the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way" to earn merit.

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together on one 16-foot-long scroll. Because virtually all original Indian scriptures have been lost Chinese translations of Indian scriptures have been invaluable in trying to figure out what the original Indian texts said.

See Separate Articles DIAMOND AND LOTUS SUTRAS AND CHINESE BUDDHIST TEXTS factsanddetails.com

World's earliest printing, from a Chinese Buddhist sutra

Chinese Buddhist Schools and Sects

As Buddhism developed it splintered into many schools and sects, each with its own distinctive traditions, doctrines and practices. Sub-sects — representing lineages of disciples that split off from the main schools often over minor doctrinal differences — and cults — that conducted special observances and rituals often focused on a particular sutra and kept alive by a lineage of masters — also developed. Despite the large number of groups and subgroups monks tended to be initiated into the general Buddhist community rather than into a particular school, sect or cult.

Schools and sects in China generally fall into one of three categories: 1) classical schools, which are based on a particular sutra and trace their origin back to India; 2) catholic sects, based on different sutras, often ones oriented toward reaching enlightenment selected by the founder of the sect; and 3) exclusive sects, which advocate a single path and select the systems and sutra to suit that purpose.

The two exclusive sects are: 1) Pure Land and 2) Cha’an.The four principal classical schools are :1) the Kola School, based on doctrines from India translated by Xuanzang (Hsuan Tsang); 2) the Satyasiddho School, based on Kumarajiva's translation of the Satyasiddhi sutra; 3) the San-Lun (Three Treatises) School; 4) the Fa-hsiang School, founded by Xuanzang.

The three primary Chinese Buddhist sects are: 1) Tien-tai (T'ien-t'a), founded by Chih-I (A.D. 538-97) and oriented around the Lotus sutra and a system of meditative exercises; 2) Hua-yen, founded by Tu-Shan (A.D. 557-640), refined by Fa-tsang (643-712) and based on the Avatamsaka (Hua-yen) sutra; and 3) Chen-yen (True Word), introduced by Indian missionaries about A.D. 720.

The Tien-tai school has its own liturgy. Followers believe that the secret of enlightenment lay in a balance of meditation, moral discipline, rituals and study of scriptures. The Hua-yen sect emphasizes a step-by-step approach to enlightenment, featuring meditation exercises aimed at discovering the Realm of Essence.

Members of the Chen-yen Schools use secret ceremonies, mime and spells to achieve salvation. It features a ten-stage system of religious life, a baptism-like consecration and meditation exercises based on contemplating symbolic representations of the five chief Buddhas using certain spells and chants and ritual gestures repeated again and again.

See Separate Article CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com CH'AN SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Buddhism and Other Chinese Religious Traditions

Mario Poceski wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”: The history of Chinese religions is usually discussed in terms of the "three teachings": Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. China's religious history during the last two millennia was to a large extent shaped by the complex patterns of interaction among these three main traditions and popular religion. The history of Buddhism in China was significantly influenced by its contacts with the indigenous traditions, which were also profoundly transformed through their encounter with Buddhism. [Source: Mario Poceski, “Encyclopedia of Buddhism”, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

“The initial arrival of Buddhism into China during the Han dynasty coincided with the emergence of religious Daoism. During the early period the acceptance of Buddhism was helped by the putative similarities between its beliefs and practices and those of Daoism. With the increased popularity and influence of Buddhism, from the late fourth century onward Daoism absorbed various elements from Buddhism. In the literary arena, that included large-scale adoption of Buddhist terminology and style of writing. The Daoist canon itself was modeled on the Buddhist canon, following the same threefold division. In addition, numerous Buddhist ideas—about merit, ethical conduct, salvation, compassion, rebirth, retribution, and the like—were absorbed into Daoism. The Buddhist influence also extended into the institutions of the Daoist church, and Daoist monasteries and temples were to a large extent modeled on their Buddhist counterparts.

“During the medieval period, intellectual and religious life in China was characterized by an ecumenical spirit and broad acceptance of a pluralistic outlook. The prevalent view was that the three traditions were complimentary rather than antithetical. Buddhism and Daoism were primarily concerned with the spiritual world and centered on the private sphere, whereas Confucianism was responsible for the social realm and focused on managing the affairs of the state. Even though open-mindedness and acceptance of religious pluralism remained the norm throughout most of Chinese history, such accommodating attitudes did not go uncontested. In addition to the Confucian criticisms of Buddhism, which repeatedly entered public discourse throughout Chinese history, there were occasional debates with Daoists that were in part motivated by the ongoing competition for official patronage waged by the two religions.

“More conspicuous expressions of exclusivist sentiments came with the emergence of neo-Confucianism during the Song period. The stance of leading Confucian thinkers toward Buddhism was often marked by open hostility. Notwithstanding their criticism of Buddhist doctrines and institutions, neo-Confucian thinkers drew heavily on Buddhist concepts and ideas. As they were trying to recapture intellectual space that for centuries had been dominated by the Buddhists, the leaders of the Song Confucian revival remade their tradition in large part by their creative responses to the encounter with Buddhism.

“Throughout its history Chinese Buddhism also interacted with the plethora of religious beliefs and practices usually assigned to the category of popular religion. Buddhist teachings about karma (action) and rebirth, beliefs about other realms of existence, and basic ethical principles became part and parcel of popular religion. In addition, Buddhist deities—such as Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion—were appropriated by popular religion as objects of cultic worship. The influence went both ways, as popular deities were worshiped in Buddhist monasteries and Buddhist monks performed rituals that catered to common beliefs and customs, such as worship of ancestors.

See Separate Articles EARLY HISTORY AND ARRIVAL OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com LATER HISTORY OF BUDDHISM IN CHINA: FROM THE TANG DYNASTY TO MAO factsanddetails.com

Buddhism, Taosim and Confucianism

Confucius, Laozi and Buddha

Buddhism developed in China through its interaction with other Chinese religions, particularly Taoism. Within Buddhism there was a great deal of flexibility in what was required of followers and it was not necessary for followers to dispense with their beliefs in other religions. Many Chinese followed Buddhism and Taoism at the same time. Even so Buddhism and Taoism were rivals. The Six Dynasties Period overlapped with the Age of Faith (A.D. 3rd to 7th centuries A.D.), a period when Taoists and Buddhists fought for dominance in China.

In some ways Taoism and Buddhism were similar. They both promised followers salvation, stressed detachment and incorporated many superstitions. But in other ways they were very different. Taoism, for example, aspired to make a person physically immortal in their own bodies while Buddhism regarded the human body as a temporary vessel that would ultimately be discarded. Buddhism was able to win many coverts from Taoism by placing a strong emphasis on moral conduct and analytical thinking criticizing the foggy cosmology and superstitious and ritualistic nature of Taoism.

Confucianism, China's oldest and most influential system of thought, is named after its founder, Confucius (Kong Qiu, 551-479 B.C.). Although sometimes characterized as a religion Confucianism is more of a social and political philosophy than a religion. Some have called it code of conduct for gentlemen and way of life that has had a strong influence on Chinese thought, relationships and family rituals. Confucianism stresses harmony of relationships that are hierarchical yet provide benefits to both superior and inferior, a thought deemed useful and advantageous to Chinese authoritarian rulers of all times for its careful preservation of the class system.

Taoism is some ways developed as a response to Confucianism. These two schools of thought are central to Chinese culture and history. The focus of Taoism is the individual in nature rather than the individual in society. It holds that the goal of life for each individual is to find one's own personal adjustment to the rhythm of the natural (and supernatural) world, to follow the Way (dao) of the universe. In many ways the opposite of rigid Confucian moralism, Taoism served many of its adherents as a complement to their ordered daily lives. A scholar on duty as an official would usually follow Confucian teachings but at leisure or in retirement might seek harmony with nature as a Taoist recluse. [Source: The Library of Congress; [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University ]

With competition from Taoism and Buddhism — beliefs that promised some kind of life after death — Confucianism became more like a religion under the Neo-Confucian leader Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi, A.D. 1130-1200). In an effort to win converts from Taoism and Buddhism, Zhu developed a more mystical form of Confucianism in which followers were encouraged to seek “all things under heaven beginning with known principals “and strive “to reach the uppermost." He told his followers, “After sufficient labor...the day will come when all things suddenly become clear and intelligible." Important concepts in Neo-Confucian thought were the idea of “breath “(the material from which all things condensed and dissolved) and yin and yang.

Saniiao (the Three Teachings): Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Most anthologies of Chinese religion are organized by the logic of the sanjiao (literally “three teachings”) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Historical precedent and popular parlance attest to the importance of this threefold division for understanding Chinese culture. One of the earliest references to the trinitarian idea is attributed to Li Shiqian, a prominent scholar of the sixth century, who wrote that “Buddhism is the sun, Daoism the moon, and Confucianism the five planets.” [Li’s formulation is quoted in Beishi, Li Yanshou (seventh century), Bona ed. (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1974), p. 1234. Translation from Chinese by Stephen F. Teiser, Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

Three Teachings

“Li likens the three traditions to significant heavenly bodies, suggesting that although they remain separate, they also coexist as equally indispensable phenomena of the natural world. Other opinions stress the essential unity of the three religious systems. One popular proverb opens by listing the symbols that distinguish the religions from each other, but closes with the assertion that they are fundamentally the same: “The three teachings — the gold and cinnabar of Daoism, the relics of Buddhist figures, as well as the Confucian virtues of humanity and righteousness — are basically one tradition.” [The proverb, originally appearing in the sixteenth-century novel Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen yanyi), is quoted in Clifford H. Plopper, Chinese Religion Seen through the Proverb (Shanghai: The China Press, 1926), p. 16.]

“The three teachings are a powerful and inescapable part of Chinese religion. Whether they are eventually accepted, rejected, or reformulated, the terms of the past can only be understood by examining how they came to assume their current status. And because Chinese religion has for so long been dominated by the idea of the three teachings, it is essential to understand where those traditions come from, who constructed them and how, as well as what forms of religious life (such as those that fall under the category of “popular religion”) are omitted or denied by constructing such a picture in the first place.

“It must also be noted that the focus on the three teachings privileges the varieties of Chinese religious life that have been maintained largely through the support of literate and often powerful representatives, and the debate over the unity of the three teachings, even when it is resolved in favor of toleration or harmony — a move toward the one rather than the three — drowns out voices that talk about Chinese religion as neither one nor three. Another problem with the model of the three teachings is that it equalizes what are in fact three radically incommensurable things. Confucianism often functioned as a political ideology and a system of values; Daoism has been compared, inconsistently, to both an outlook on life and a system of gods and magic; and Buddhism offered, according to some analysts, a proper soteriology, an array of techniques and deities enabling one to achieve salvation in the other world. Calling all three traditions by the same unproblematic term, “teaching,” perpetuates confusion about how the realms of life that we tend to take for granted (like politics, ethics, ritual, religion) were in fact configured differently in traditional China.”

Image Sources: 5th century Bodhisattva, University of Washington; Printing, Brooklyn College; Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021