CONFUCIAN TEMPLES

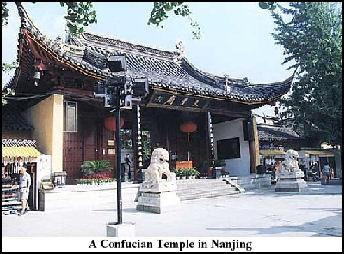

Like other Chinese temples, Confucian temples are often comprised of many buildings, halls and shrines. They tend to be situated in the middle of towns and have north-south axises. Large halls, shrines and important temple buildings have traditionally been dominated by tiled roofs, which are usually green or yellow and sit atop eaves decorated with religious figures and good luck symbols. The roofs are often supported on magnificently carved and decorated beams, which in turn are supported by intricately carved stone dragon pillars. Many temples are entered through the left door and exited through the right.

Like other Chinese temples, Confucian temples are often comprised of many buildings, halls and shrines. They tend to be situated in the middle of towns and have north-south axises. Large halls, shrines and important temple buildings have traditionally been dominated by tiled roofs, which are usually green or yellow and sit atop eaves decorated with religious figures and good luck symbols. The roofs are often supported on magnificently carved and decorated beams, which in turn are supported by intricately carved stone dragon pillars. Many temples are entered through the left door and exited through the right.

Confucian temples house a spirit tablet dedicated to Confucius himself, along with a collection of spirit tablets dedicated to various important scholars in the Confucian canon (many of these being Confucius’ own disciples; others would be eminent Confucian scholars from later times). Rites at the Confucian temple were held by and for government officials of the district, as well as for the vastly larger number of degree-holders not in office. All the degree-holders of a district were required to attend the annual worship at the temple of Confucius on his birthday.

The main feature of the Confucian Temple in Beijing are the rows of steles in the front that honor scholars and bureaucrats who passed the imperial civil service exam. The Confucius Temple in Qufu has halls that are laid out along a symmetrical north-west axis. In the 22-acre temple grounds are many large trees and small gardens as well as 28 stone columns and bas-reliefs of clouds and dragons. The Terrace of Apricot, a tile-roofed platform, is where Confucius used to give lectures to his disciples. Offerings are regularly made at altars around the temple.

Priests in Confucian shrines today in China are generally little more than caretakers. In the Mao era, temples were often used as storehouse for the local production team. Many were destroyed by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. The Confucian temple in Qufu was sacked as Confucius was denounced as a class enemy. An enormous statue of Confucius was dragged through the streets and smashed with sledge hammers. His grave was dug up to show he wasn't there. The temples have since been restored but statues and the ancestral tablets destroyed by the Red Guards have not been replaced.

Good Websites and Sources on Confucianism: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Confucianism religioustolerance.org ; Religion Facts Confucianism Religion Facts ; Confucius .friesian.com ; Confucian Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Cult of Confucius /academics.hamilton.edu ; ; Virtual Temple tour drben.net/ChinaReport; Wikipedia article on Chinese religion Wikipedia Academic Info on Chinese religion academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Qufu Wikipedia Wikipedia Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIUS: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER, DISCIPLES AND SAYINGS factsanddetails.com; CHINA AT THE TIME CONFUCIANISM DEVELOPED factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY SOCIETY: FROM WHICH CONFUCIANISM EMERGED factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; NEO-CONFUCIANISM, WANG YANGMING, SIMA GUANG AND “CULTURAL CONFUCIANISM” factsanddetails.com; ZHU XI: THE INFLUENTIAL VOICE OF NEO-CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEXTS factsanddetails.com; ANALECTS OF CONFUCIUS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM, GOVERNMENT AND EDUCATION factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AS A RELIGION factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND SOCIETY, FILIALITY AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM IN MODERN CHINA: CAMPS, FEEL GOOD CONFUCIANISM AND CONFUCIUS'S HEIRS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; ZHOU RELIGION AND RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com; DUKE OF ZHOU: CONFUCIUS'S HERO factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.): UPHEAVAL, CONFUCIUS AND THE AGE OF PHILOSOPHERS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM DURING THE EARLY HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TEMPLES factsanddetails.com ; RELIGIOUS TAOISM AND TAOIST TEMPLES AND RITUALSfactsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES AND MONKS factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Confucianism “Confucianism: A Very Short Introduction” Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Confucianism” by Jennifer Oldstone-Moore Amazon.com; Confucius, His Life and Time "Confucius, The Man and the Myth" by Herrlee Creel (1949, also published as "Confucius and the Chinese Way", a classic account of Confucius’s biography Amazon.com; "The Authentic Confucius: A Life in Thought and Politics" by Annping Chin, (New York: 2007) Amazon.com; “Lives of Confucius: Civilization's Greatest Sage Through the Ages” by Michael Nylan and Thomas Wilson Amazon.com; “Quotes of Confucius And Their Interpretations” by D. Brewer Amazon.com; “Philosophers of the Warring States: A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy” by Kurtis Hagen and Steve Coutinho Amazon.com ; Analects and Confucian Texts: Good translations of the “Analects” have been done by Arthur Waley (1938) Amazon.com; D.C. Lau (Penguin Books, 1987, 1998) Amazon.com; “The Analects” (Penguin Classics) by Confucius and Annping Chin Amazon.com; and Edward Slingerland (2003) Amazon.com.

Kong Miao (Temple of Confucius) in Qufu

Confucian Temple in Qufu

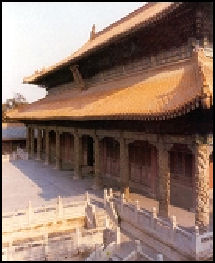

Holy places of Confucianism include Temple of Confucius, Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu, Shandong Province, the hometown of Confucius. Kong Miao (Temple of Confucius) in Qufu was originally built as a home for Confucius's oldest son. It covers 49 acres and is a fine example of classical Chinese architecture. One traveler described it as a “magnificent sweep of lines, with eaves curving up towards the stars." All around are cypress trees, which symbolize the firmness of the Confucian character. The Confucius Temple and Cemetery are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The halls are laid out along a symmetrical north-west axis. In the 22-acre temple grounds are many large trees and small gardens as well as 28 stone columns and bas-reliefs of clouds and dragons. The Terrace of Apricot, a tile-roofed platform, is where Confucius used to give lectures to his disciples. Offerings are regularly made at altars around the temple.

Thomas A. Wilson of Hamilton College wrote: “The main hall is the large temple in the center. Just in front of the main hall is the Apricot Altar, where Confucius was said to lecture. Behind the main hall is the Hall of Repose, where the spirit of Confucius's wife, Qiguan, is housed. The two long corridors that run along the sides of the Main Hall, Hall of Repose, and Apricot Altar are the east and west cloisters where secondary sacrifices occur. At the front of these two corridors is the "Great Completion" gate. |[Source: Thomas A. Wilson, Hamilton College, the Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu ]

“Behind the temple complex are two small structures: the Tutelary Spirit of the Land on the upper right and the Silk Burning Furnace on the upper left. The Hall of Odes and Rites are on the east side of the main temple complex. The Hall of Odes and Rites is named because, supposedly, Kongzi admonished his grandson, Kong Ji (Zisi) about minding his studies of the Book of Rites and the Book of Odes. Through the gate north of this hall is the Kong family Ancestral Shrine. Finally, the "Spirit Kitchen" is located in the northeast corner of the complex. The temple complex to the west side of the main hall (left) is devoted to Confucius's father, Shuliang He. ]

History of the Temple of Confucius

Confucius's Tomb in Qufu According to the Asian Historical Architecture: “Kong Miao, the Temple of Confucius, is located in Qufu in Shandong province. The origins of the temple date back to the 5th century B.C., shortly after the Sage's death. In 478 B.C., Duke Ai of the state of Lu (in today's Shandong Province) built a temple honoring Confucius, who was still largely unknown outside the province. By the 2nd century B.C., the fame of Confucius had spread and the Han emperor Wudi began offering sacrifices at this site in 205 B.C. The temple was expanded but subsequent generations of rulers, and for the next thousand years, untold numbers of buildings were built and torn down in many rounds of rebuilding. [Source: Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com ]

“In 739, the Tang dynasty posthumously honored Confucius as Prince Wenxuan. Under the subsequent Song dynasty, scholars such as Zhu Xi (1130-1200) breathed new life into Confucianism by synthesizing what had been a largely moralistic philosophy of sage kings with a coherent metaphysical framework that accounted for all reality in humanist terms. With greater emphasis placed on education and the role of master-disciple learning, Confucian academies began to appear across China in great numbers. These academies followed the form of the White Deer Grotto Academy of Zhu Xi, which in turn was based on the layout of the Temple of Confucius. Through such institutions, Kong Miao became a protypical institution that exerted architectural influence into Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. A particularly powerful example is Dosan Seowon Academy in Korea, which became an essential prototype of future academies in that country.

“The precise layout of the Temple of Confucius as seen today largely dates from the early 16th century, when the temple was rebuilt following a massive conflaguration in 1499 sparked by lightning. Since it was built almost at the same time as the Forbidden City in Beijing, there are many design similarities between the two complexes. Particularly in terms of color, both make full use of red walls, yellow roofs, and white marble stonework. The axial layout of the Forbidden City and its use of nested courtyards is another design feature held in common with Kong Miao.

“A visitor to Kong Miao enters on the south side through a succession of gates. After passing through four courtyards lined in succession, one arrives at the Star of Literature pavilion. This hall, first built in 1098 and then rebuilt in 1191 with its present name, is seven bays across and two stories tall. The upper story contains a library (accounting for its name) while the lower story was used as a residence hall for the master of ceremonies and his assistants at the temple.

“After passing through this hall, the visitor encounters the Gate of Great Achievement, which is the only gate outside the Forbidden City that is five bays across. The gate adjoins a two covered corridors that branch off to the north, forming an enclosed quadrangle that houses the Hall of Great Achievement. In formal layout, the placement of this hall is identical to the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the Forbidden City, where the reigning Emperor maintained his throne. The four towers at the corners of the quadrangle—an architectural feature reserved for rulers—reinforces the sense that the temple honors an individual of great rank almost equal to the Emperors.”

Confucian Temple Comes to Life

In 2010, the first service at Beijing's Confucian temple was held since the Communists took power in 1949. Hundreds of schoolchildren gathered to pay their respects. Dancers in red robes and students in flowing black drifted through the courtyards of the 14th century temple complex in central Beijing. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, September 28, 2010 /~/]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: ““In my fifth year in Beijing, I moved into a one-story brick house beside the Confucius Temple....The temple was built in 1306, near the Imperial Academy, a training ground for officials, which remained China’s highest seat of learning until the fall of the emperor, in 1911....The temple, which shared a wall with my kitchen, was silent. It had gnarled cypress trees and a wooden pavilion that loomed above my roof like a conscience. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, January 13, 2014]

In September, 2010, nine months after I moved in, I was at my desk one morning when I heard a loudspeaker crackle to life inside the temple. A booming voice was followed by the sound of a heavy bell, then drums and a flute, and the recitation of passages from writings by Confucius and other ancient masters. The performance lasted twenty minutes. An hour later, it was repeated, and an hour after that, and again the next day.

“Every day, I noticed groups of civil servants from the hinterlands and students from around the city visiting the Confucius Temple. One young guide with a ponytail spoke to a group of middle-aged Chinese women. She held her hands out before her. “This is the gesture for paying respects to Confucius,” she said. Her visitors did their best to copy her. For many people in China, I realized, the gaps in history had made Confucius a stranger. It was difficult to know where his life ended and the mythology and the politics began. Annping Chin wrote, “We give him credit for all that has gone right and wrong in China because we do not really know him.”

“The longer I lived beside the Confucius Temple the more I sensed the gap between what people asked of it and what it provided. The Chinese came to the temple, to the Holy Land of National Studies, on a quest for some kind of moral continuity. But it rarely gave them what they wanted. The Party, to maintain its hold over history, offered a caricature of Confucius. Generations of Chinese had grown up condemning China’s ethical and philosophical traditions, only to find that the Party was now abruptly resurrecting them, without granting permission to discuss what had happened in the interim. Hu Shuli, a progressive editor, described a “collective amnesia” surrounding the Cultural Revolution. “Files on that episode in our history remain ‘secret,’ ” she wrote. “Older generations do not dare look back, while our younger generations don’t have the remotest inkling of the Cultural Revolution.”

Autumnal Sacrifice to Confucius

Qing Emperor Yongzheng offering sacrifices at the Altar of the God of Agriculture

Thomas A. Wilson of Hamilton College wrote: “At the heart of Confucianism is the practice of ritual, particularly through sacrifice. With the belief that individuals are composed of two parts, a light yang spirit called hun and a heavy yin corporeal ghost called po, Confucians believed that after death, the hun rose upward while the po decomposed in the earth. To earn the spirits' favor, as well as pay their own respect, Confucians performed sacrificial rites to offer the spirits sustenance. In the Confucian tradition, there are three levels of sacrificial ritual: Great Sacrifice offered by the emperor, Middle Sacrifice offered by court officials, and Minor Sacrifice offered by local officials. Sacrifices to Confucius were ranked as at the Middle level and held twice a year; once in the autumn and once in the spring. [Source: Thomas A. Wilson, Hamilton College, the Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu ||]

“The Autumnal Sacrifice to Confucius follows the standardized sequence of ritual activities first established before the Tang dynasty (618-907). The first imperial sacrifice is often dated to 195 BCE under the reign of Emperor Gaozu (r. 206-195 BCE). This first imperial sacrifice consisted of the Han offering a large beast sacrifice of an ox, goat, and pig to Kongzi's spirit. Additionally, the music and dance were first standardized by of the Southern Qi (479-502) dynasty in 485. The six stages of ritual throughout most of imperial China were: Second offering of wine and food to the deities. ||]

“In traditional sacrifices, the sacrifices were prepared in the Spirit Kitchen at the southwest corner of the temple complex. While Kongzi, sages, correlates, and savants were sacrificed to in the Main Hall, the worthies and scholars received sacrifice in the eastern and western cloisters, the long corridors running along the temple complex.” ||

Description of a Sacrifice to Confucius

Describing the sacrifice as it is carried out today in Taiwan, Wilson wrote: “Two ritual officers take the blood and fur from the primary sacrifice to bury outside the main temple gate. As incorporeal, yet discrete beings, the spirits were attracted to the ceremonial site by the scent of the blood and fur. In addition to attracting the spirits, the burying of the blood and fur also informed the spirits that a full animal was being offered. [Source: Thomas A. Wilson, Hamilton College, the Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu ||]

“Traditionally, the main sacrificial victim is chosen and carefully tended to for a month prior to the ceremony. On the day before the ceremony, the sacrificial victims are brought to the "spirit kitchen," an area typically in the back corner of the temple complex. A ritual officer inspects the kitchen utensils and ritual vessels for cleanliness and the victims for plumpness. Assuming everything is in order, the victims are then slaughtered. Some of the blood and fur from the sacrificial victims is set aside in a pan, later to be buried outside the main temple gates, and the animals are cleansed with boiling water. In this ceremony, the sacrificial victims were chosen beforehand at a slaughterhouse and killed there, rather than in the temple complex. ||

Tang oxen

“Although the fur and blood lured spirits to the feast initially, the majority of the sacrificial feast consisted of simple fare. Canonical sources admonished those who offered extravagant or expensive foods; spirits preferred simple fare, including unseasoned broth, grains, and edible grasses. The meat that was served was typically raw or dried. Prior to the ceremony, a ritually purified officer consecrates the offerings.” ||

The sacrifice concludes with a Silk Burning ceremony. “In this temple, the Silk Burning Furnace is located just behind the temple complex along the outer walls. In this filmed ritual, however, the Silk Burning Furnace was located outside the main gate. “After the feast is cleared and the meat is received, the prayer that was read earlier is brought ouside the main gate and burned. Though the prayer has already been read, the prayer is burned to ensure receipt of the prayer in the heavens. By burning the prayer, the smoke carries the message to the heavens and makes sure the intended recipients hear the prayer. Because spirits are ethereal, they have no use for material goods. As such, the silk, which was believed to be the currency in the afterlife, was also burned and carried up to the heavens via the similarly ethereal smoke. After the conclusion of the sacrifice, members of the audience pull hair from the sacrificial ox. The hair is seen as a good luck charm and is brought home and sometimes placed on personal altars. ||

Videos of the Autumnal Sacrifice to Confucius filmed in Tainan, Taiwan can be found at Wilson’s site: Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu . The sacrifice was filmed by Brooks Jessup and Thomas A. Wilson in 1998 in Tainan, Taiwan. Each video is accompanied by a brief description of what is happening, as well as some of the historical background and importance. All videos are subtitled in English and a transcript of the translated hymns accompanies the appropriate videos. ||

State Temples of Confucianism

Thomas A. Wilson of Hamilton College wrote: “The first state temple devoted to Kongzi was built in the Liu-Song, which ruled over south China from 420 to 479. The Confucius temple in Bejing was first built in 1302, and was periodically repaired and rebuilt during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. The Hall of Great Completion (Da cheng dian) is situated northeast of the Forbidden City. [Source: Thomas A. Wilson, Hamilton College, the Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu ||]

“Beginning in the Tang era, and particularly from Song times on, the state sacrifices to Confucius in the capital became increasingly complex and closely regulated by an official liturgy. When the founder of the Southern Song dynasty reestablished the capital in Lin'an (modern Hangzhou), an imperial Confucius Temple was constructed. ||

“Kongzi's forty-eighth generation descendant, Duke Kong Duanyou, followed the Song emperor, and established the southern Kong lineage. By 1136 the Kongs settled in Quzhou, Zhejiang, where they converted the local school temple into a temple operated by Kongzi's descendants. Later a family temple honoring Kongzi was established at a nearby lake. Around 1279, when the Southern Song fell, this temple was destroyed by fire, and was not rebuilt until 1407. The present-day Quzhou Confucius temple was moved to its current location in 1520. ||

“Besides promoting a specific curriculum in the examination halls, the court also articulated its understanding of Confucian orthodoxy in a temple called the Kong temple, or the Temple of Culture. Here the spirits of Kongzi, his disciples, and later canonical exegetes and "transmitters of the Way" were enshrined and received sacrifices from representatives of the emperor. The question of which Confucians of later ages would be enshrined in the temple was controversial because it raised such issues as which commentaries on the Confucian canon were acceptable and, by the Song, who was believed to have received the true transmission of the Dao from Kongzi and Mengzi (Mencius). A basic chronology of enshrinement shows the gradual canonization of the Dao School version of the Confucian tradition, beginning in the 1240s and particularly by Ming times. ||

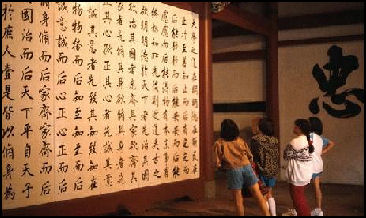

“In addition to hosting sacrifices, the Confucius Temple also served to enshrine Confucian teachings and doctrines. After it integrated the cult of Confucius into the imperial pantheon in the Tang dynasty (618 - 907), civil officials never ceased to debate the cult's meaning. In the early years of the cult, the court wavered on the central question of who was its principal sage, for, perhaps surprisingly, Confucius did not always hold this status. In subsequent years the court also added spirit tablets of other scholars, in effect endorsing the doctrines they taught. As a cult devoted to the spirits of men of surpassing classical learning, its rituals were necessarily bound up with the curriculum used to educate men preparing for civil examinations based on the Confucian Classics. One hundred ninety-eight carved stone tablets that still stand in front of the main gate of the Temple in Beijing best illustrate the Confucius Temple's integral connection with the examination system: they bear over fifty thousand names of men who passed the highest examination beginning in 1313, the date of the first examination to be held in the capital city of Beijing, to 1904, when the last civil examination was held there. The Libationer of the Directorate of Education led the new degree-holders who had passed the Palace Examination to the Temple to pay obeisance to the Supreme Sage. ||

Map of a Confucian temple

“According to most accounts, a temple honoring Kongzi was built in his hometown in 478 B.C. (17th year of Duke Ai of Lu), a year after his death. The sources suggest that, since the early years of this temple, the spirits of Kongzi and his disciples were represented with wall paintings and clay or wooden statues. After years of court debate, it was decided in 1530 that these spirits would not be represented by an iconic image of his likeness in the imperial temples in the capital and other bureaucratic locations. Opponents of iconic representations of Kongzi argued that such statues copied Buddhist practices of temple worship and also tended to confuse ritual ideas in ancestral sacrifice. They argued that imperial temples were constructed to honor Kongzi's teachings, not just the spirit of the flesh-and-blood man. The statues of Kongzi were removed from official temples, but they remained in the temples operated by Kongzi's family descendants, such as this statue of Kongzi in the Main Hall of Great Completion of the Confucius Temple in Qufu. ||

“Evidence suggests that as early as the eleventh century, Confucius temples had rooms to pay sacrifices to Confucius' father Shuliang He, and in 1048, a hall was built for this purpose. During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, ritualists explored the connection between the family cult of Confucius' descendants and the state cult of Confucius. When Shuliang He was posthumously honored as Duke who Gave Birth to the Sage, shrines called the Shrine for the Duke who Gave Birth to the Sage (Qisheng ci) were constructed to honor Confucius' father. The shrine in Qufu pictured here, was located immediately west of the Hall of Great Completion in 1729. The Qufu shrine has fallen into disrepair and is currently undergoing renovation; pictured here is the spirit statue of Shuliang He.” ||

Temple of Heaven (Tiantan)

Temple of Heaven in Beijing has been described as "the noblest example of religious architecture in the whole of China." Known to Chinese as Tiantan, it was built in 1420 and expanded and reconstructed during the reigns of the Emperor Jiajing and Emperor Qianlong. In 1998 it was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The temple is comprised of several buildings and walls with numerous gates. Each piece of architecture has symbolic meaning. The four central columns, for example, represent the four seasons. The square ends represent the earth, and the semicircles, the heavens. Among the interesting sights in the park are the Imperial Vault of Heaven with a gilded cupola and the three-tiered Circular Alter. The imperial north-south axis that runs from the Temple of Heaven to the Forbidden City to the main Olympic site.

Temple of Heaven in Beijing

According to the Asian Historical Architecture: “Tiantan, the Temple of Heaven, was established in 1420 during the reign of Ming Emperor Yongle (r. 1403-1424), who also founded the Forbidden City. The temple was originally established as the Temple of Heaven and Earth, but was given its current name during the reign of Ming Emperor Jiajing (r. 1522-1567), who built separate complexes for the earth, sun, and moon. The architecture and layout of the temple of Heaven is based on elaborate symbolism and numerology. In accordance with principles dating back to pre-Confucian times, the buildings in the Temple of Heaven are round, like the sky, while the foundations and axes of the complex are rectilinear, like the earth. The symbolism of the temple was necessary since the complex served as the setting in which the Emperor, the Son of Heaven, directly beseeched Heaven to provide good harvests throughout the land. This was important since agriculture was the foundation of China's wealth in the imperial period. Since the ceremony at Tiantan was thought to directly affect the people's livelihood, news of the ceremony each year was disseminated throughout China. [Source: Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com]

“Three principle structures lie along the primary north-south axis of Tiantan. At the southern end sits the Altar of Heaven, an empty three-tiered plinth that rises from a square yard.Constructed in 1530 and rebuilt in 1740, it is built of white marble. The number of stones in the various tiers are all multiples of three — a prevailing numerological theme at Tiantan. Next along the axis is the Echo Wall and the Imperial Vault of Heaven. The echo wall, named for its acoustical properties, permits a whisper spoken at one end to be heard from the other. The Triple Echo Stones in the courtyard return various numbers of echos depending on the stone one stands on. The Imperial Vault of Heaven, which sits in the center of the plaza, is a round building that once contained memorial tablets of the Emperor's ancestors.

“At the north end of the compound is the hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, an impressive three-tiered wooden structure that sits on a tri-level marble plinth. It was constructed in 1420 but burned in 1889. It was rebuilt soon after with some of the wood imported from the western United States. The hollow interior is magnificently decorated and contains a large ceremonial throne facing south. In modern times ceremonies have of course ceased, and the Temple of Heaven has been converted into a park popular with foreigners and residents alike.”

Temple of Heaven Ceremony

Temple of Heaven altar The Temple of Heaven is where the Ming and Qing Emperors worshiped to heaven and prayed for bumper crops. Each year, on the winter solstice, the Emperor offered a sacrifice to bring good fortune in the coming year and maintain harmony with heaven. It was the most important event on the emperor's calendar. In the spring the Emperor presided over a harvest ceremony, intended to ensure good harvests in the following autumn. Each ceremony was held at its own altar at the Temple of Heaven.

Before the Worshiping Heaven Ceremony on the winter solstice the Emperor entered the Hall of Abstinence at the Imperial Palace in the Forbidden City to pray and fast. For three days the Emperor could not eat meat or drink wine, have contact with women, make merry and take care of legal matters. After that he spent some time in the Imperial Vault, ritually communicating with the gods before spending the night in the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvest

On the day of the ceremony the Emperor traveled with an entourage that included elephant chariots, flagbearers, horse chariots, noblemen, musicians and acrobats to the altar where the ceremony was held. In a ceremony that was closed to the public the emperor chanted prayers and presided over sacrifice of animals on sacred tablets on a round Altar of Heaven.

Chinese Spirit Tablets

Instead of having an ancestor altars, some families pay to have ancestral tablets set up in temples, where priests pray to the deceased every day. Some temples in Hong Kong charge up to $30,000 for a tablet set in a prime spot.

Spirit tablet

According to the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Missouri: “Chinese religion, with its complex blend of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and folk traditions, involves a wide variety of practices and related paraphernalia. Spirit tablets are one type of ritual object commonly seen in temples and shrines and on household altars. Usually of wood, these small plaques bear inscriptions honoring ancestors, gods, and other important figures. [Source: Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri ]

“Throughout China, ancestors have traditionally been worshipped with sacrifices, shrines, and ancestor tablets. Ancestor tablets vary in size and shape in different parts of the country, but typically consist of a one- or two-piece tablet set up on a pedestal. The tablets are inscribed with the title and name of the deceased, dates of birth and death, and additional information such as place of burial and the name of the son who erects the tablet.

“The customs involved in installing ancestor tablets in the family shrine also vary by region, although there are some common practices. Often two tablets are made – one of paper and one of wood. A ceremony takes place in which the ancestor’s spirit is transferred to the wooden tablet. Once the transfer is successful, the paper tablet is either burned or buried with the dead person. After the funeral service, the tablet is taken back to the family’s house and housed in a shrine. There are usually three shrines for ancestor tablets per house. The center shrine is reserved for the primary family ancestor, or Shin Chu, who is placed in the middle of the shrine. The rest of the middle shrine is filled with the next most important family members. All the other male family members’ tablets are housed in the other two shrines; occasionally their wives’ tablets join them.

“In addition to ancestor tablets, there are also spirit tablets devoted to the host of deities that preside over the cosmos. These are placed in temples or wayside shrines and serve to honor these figures and to protect the community. This online exhibit presents ancestor tablets and general spirit tablets collected in China in the early 20th century.”

Ancestor Veneration Temples and Communal Houses

Inside Confucian Temple The cult required an ancestral home or patrimony, a piece of land legally designated as a place devoted to the support of venerated ancestors. Ownership of land that could be dedicated to the support of the cult was, however, only a dream for most landless farmers. The cult also required a senior male of direct descent to oversee preparations for obligatory celebrations and offerings. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Ancestor Veneration Temples: Temples for the veneration of ancestors have traditionally been a vital part of the Chinese scene. Due to the influence of Confucianism, there used to be a number of temples where Chinese went for worship and pray to the spirits of deceased ancestors. Each temple is dedicated the spirits of the ancestors. As a rule, these temples do not have Buddhas or Buddhist symbolism; but are richly ornamented in Chinese designs, and contain altars covered with items acceptable to this type of worship (incense burners, candles, pictures of the deceased etc.). Many were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

A communal house is often the place where memorial tables to the deceased are stored; and is the location for occasional ceremonies of the clan, tribe, or village. The pagoda or temple, the Communal House, and the market place have traditionally been the three most important places in a village or community.

Ancestor Worship Rites

Candles are regularly lit and offerings are made at ancestral shrines and graves, which are often visited during holidays. On the anniversary of an ancestor's death, rites are performed before the family altar to the god of the house, and sacrificial offerings are made to both the god and the ancestor. The lavishness of the offering traditionally depended on the income of the family and on the rank of the deceased within the family. A representative of each family in the lineage was expected to be present, even if this meant traveling great distances. Whenever there was an occasion of family joy or sorrow, such as a wedding, an anniversary, success in an examination, a promotion, or a funeral, the ancestors were informed through sacrificial offerings. [Source: Library of Congress]

Taoist ancestral ceremony

When people die, their families honor their ancestors on the day of their death by performing special ceremonies at home or at temples and by burning incense and fake money for the one who died. The Chinese believed that by burning incense, their ancestors could protect them and their family from danger and harm. Days before the ceremony starts, the family has to get ready, because they won't have enough time to get ready when the guests arrive and the ceremony starts. Usually the women cook and prepare many special kinds of food, like chicken, ham, pork, rice, and many more including desserts. [Source: Vietnam-culture.com vietnam-culture.com /*/]

While the women are busy cooking, the men are busy fixing up and cleaning up the house, so it won't be messy and dirty because of all the relatives of the person that died will come for the ceremony and show honor and respect to that person. Families venerated their ancestors with special religious rituals. The houses of the wealthy were constructed of brick, with tile roofs. Those of the poor were bamboo and thatch. Rice was staple food for the vast majority, garnished with vegetables and, for those who could afford it, meat and fish. /*/

Describing a ritual performed in a temple of the Capital True Buddhist Society in Spencerville, Maryland, the Freer Gallery of Art reported: “Food was burned as an offering to any ancestral spirits in the area, while chanting invited the spirits to the "feast." Offerings for the ancestors' spirits were made in front of the grave. A small slit was for incense. The big characters in the middle say "father" and "mother." The right side tells birth and death dates. On the left are names of family members. Inside the box are the ashes of the deceased. [Source: Freer Gallery of Art asia.si.edu ^^]

Confucius's Birthday

Confucius's Birthday is commemorated on September 28th or the 27th day of 8th lunar month with offerings made at Confucian temples all over China. The largest observation of his birthday is held in Confucius's hometown of Qufu, in Shandong Province, where, a 15 day celebration is held. People visit the Confucius Mansion and Confucius Temple; ride through Confucius Woods in ancient horse'drawn carriages; attend a reenactment of an ancient Memorial service at Confucius's tomb; watch a special dance performed by a 36-member folk troupe, using long feather wands and accompanied by a orchestra that plays solemn music on 20 different kinds of antique instruments. Rites are offered three times. Everything is done exactly as it was the first year after Confucius's death.

In 2005, a large celebration — with tens of thousand of participants, costumes and 100 scholars discussing the relevance of Confucian — was held in Qufu. In 2007 over 3,000 people showed up in Qufu to celebrate Confucius's 2,557th birthday with speeches, dances, recitations and sacrifices of a pig, a bullock and a goat. The dancers wore costumes like those worn 2,000 years ago in the Han Dynasty and prostrated themselves in front of the sage's statue.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: ““A few days after I heard the loudspeaker next door, a large banner went up in our neighborhood, identifying the temple as “The Holy Land of National Studies.” For the first time since the Communist Party came to power, in 1949, the temple was putting on a celebration of Confucius’ birthday. The occasion featured speeches by government officials and professors and a recitation by children. I figured that the event would probably signal the end of the daily musical shows, but in the weeks that followed they continued, and followed a regular schedule: every hour, ten to six, seven days a week, rain or shine. The sound echoed off the walls of the houses beside the temple, and what had begun as a novelty gradually wore grooves into the minds of my neighbors. Huang Wenyi, an employee at a recycling yard, who lived next door, told me, “I hear it in my head at night. It’s like I’ve been on a boat all day and I can still feel the rocking.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, January 13, 2014]

“The show had been conceived under demanding circumstances.” The head of the temple, a man named Wu Zhiyou, had been given only a month’s notice before the birthday celebration. He hired a composer, recruited dancers from a local art school, and selected lines from the classics that could lend the performance a narrative shape. “You need ups and downs and a climax, just like a movie or a play,” he said. “If it’s too bland, it will never work.”

“Wu had succeeded in making the Confucius Temple into his own community theatre, and he was savoring his role. “In junior middle school, I was always the student leader of the propaganda section of the student council,” he said. “I love reading aloud, and music and art.” In his spare time, he still did cross-talk comedy routines, the Chinese version of standup. He had plans for the temple’s future. “We’re building a new set that will have ceramic statues of the seventy-two disciples. And we need more lighting. Then, maybe, I can say it is complete.”

“The stage, in front of a pavilion on the north side of the compound, had been fitted with lights. The cast consisted of sixteen young men and women in scholars’ robes; each song-and-dance routine was named for a line from the classics—the Analects, the Book of Songs, the Book of Rites, and others—and had an upbeat interpretation: “Happiness” was based on the line “Good fortune lies within bad; bad fortune lies within good.” (The stage version omitted the ominous second clause.) The finale, “Harmony,” linked Confucius and the Communist Party. A pamphlet explained that it conveyed the “harmonious ideology and harmonious society of the ancient people, which will have a positive influence on the construction of modern harmonious society.”

Chronology of Confucian Temples, Enshrinement and Sacrifices

169/170 CE (Lingdi jianning 2/3): Beginning of regular Spring and Autumn sacrifices to Kongzi in Qufu, which were modeled after the liturgy of gods of soils and grains. 271 (Jin dynasty, Emperor Wu, Taishi 7): The imperial heir apparent personally offers sacrifices to Kongzi in the National University. 445 (Liu-Song dynasty, Emperor Wen yuanjia 22): The first attempt to standardize the Spring and Autumnal sacrifices. Sacrifices use six rows of dancers, three racks of hanging instruments, and the offerings and vessels used are appropriate for an upper lord. 454 (Xiaowudi xiaojian 1/10/15): First temple built outside of Lu, four years after the loss of Lu to Northern Wei 489 CE (Northern Wei dynasty, Emperor Xiaowen taihe 13/7/25): The first temple devoted to Kongzi is constructed in the capital. This is also the first temple built outside of Qufu. [Source: Thomas A. Wilson, Hamilton College, the Cult of Confucius: Images of the Temple of Culture /academics.hamilton.edu ||]

630 (Tang dynasty, Taizong zhenguan 4): Temples are established in prefectural and country state schools Kongzi received the main offering as sage in the temple of the Tang era and Yan Hui received offerings as correlate. For a short time in the seventh century the Duke of Zhou was placed in the primary position facing south as sage. In 657 the Duke of Zhou was removed and enshrined in the temple for kings of the Zhou dynasty. Also ten of Kongzi's disciples were enshrined as savants for their surpassing virtue in conduct, speech, governance, culture and learning (see Analects 11.3). 647: Twenty-two canonical commentators and exegetes from the Zhou to the Han are enshrined. 720: Seventy of Kongzi's disciples formally enshrined. ||

Qi sheng ci: 739 (kaiyuan 27/8/23): Kongzi is elevated to the Exalted King of Culture (previously known as Exalted Ni Duke of Consummate Perfection) and his image seated facing south in temples in the two Directorates of Education. 1084: Mengzi (Mencius) is enshrined as a correlate with Yan Hui. Xunzi (Hsun-tzu), Yang Xiong, and Han Yu enshrined as scholars. 1104: Wang Anshi is enshrined as correlate after Mengzi (later demoted to scholar in 1126 and removed entirely in 1241). 1241: The five masters — Zhou Dunyi, Zhang Zai, the Cheng brothers, and Zhu Xi) of the Dao School are enshrined. 1267: Zeng Can (reputed author of the Great Learning) and Kong Ji (reputed author of the Doctrine of the Mean) are promoted to correlates marking the court's recognition of the canonical status of the Four Books. Shao Yong, Sima Guang, and Lu Zuqian are enshrined. ||

1369 (Ming dynasty, Hongwu 2/): Sacrifices in schools are suspended, but they continue in Qufu. 1372 (Hongwu 5): Sacrifices to Mengzi were suspended but are resumed the following year. 1382 (Hongwu 15): The Imperial University resumes sacrifices to Kongzi. 1477 (Chenghua 13/2/8): The number of sacrificial vessels is increased from ten to twelve and the rows of dancers from six to eight. By doing so, Kongzi is effectively promoted to the status of emperor. 1496 (Hongzhi 9/2): The number of dancers is increased again, this time to 72 in accordance with the regulations for the son of Heaven. ||

1530: The five Song Confucians, including Ouyang Xiu and Lu Xiangshan, are enshrined. Thirteen scholars and canonical exegetes are removed and an additional seven are demoted to local temples. The earlier ranking system based on posthumous titles (king, duke, marquis, earl) is eliminated and the exclusive use of a hierarchy that divided the men enshrined into sage, correlate, and savant (house in the main temple), and worthy and scholar (housed in the eastern and western cloisters) is adopted. ||

Hall of Good Harvest: “1531 (Jiajing 10): The Shrine for the Duke of Giving Birth to the Sage (Kongzi's father). 1642: Six Dao School masters (Zhou Dunyi, the Cheng brothers, Zhang Zai, Shao Yong, and Zhu Xi) are elevated to status of worthy. 1712: Zhu Xi is elevated to correlate. 1724: Several of the scholars removed in 1530 are restored. ||

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei\=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021