THE ANALECTS

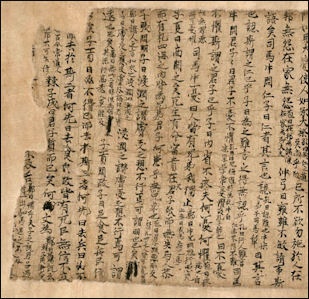

Ancient version of the Analects from Dunhuang

The principal source for the thought of Confucius is a text known as “The Analects of Confucius”. “Analects” means brief sayings or literary fragments. The original Chinese title meant “collated sayings”. Confucius reportedly compiled the sayings, aphorism, maxims and episodes that make up The Analects during his retirement. But this seems unlikely. The 20 chapters and 497 verses of The Analects were unknown until 300 years after his death. More likely they were compiled by his disciples and written down by other people. Confucius himself once said he merely "transmitted" what was taught to him "without making anything up" on his own. The first half of The Analects is stylistically and thematically very different from the second half. University of Southern California historian John Wills Jr. told Atlantic Monthly, "We have known for a long time that some of the later parts of the book are suspect. After Chapter Ten or Twelve you get a lot of fishy Taoist stuff."

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: Each chapters is “composed of a series of sayings in an order which sometimes seems cogent, but more often seems random. The text is clearly a conjoining of several smaller texts that were put together over several centuries by Confucius’s disciples and subsequent followers. It is extremely difficult to ascertain which portions of the text reliably report what Confucius actually said and did, and which belong instead to a body of legend that grew around the figure of Confucius after his death. The confusing form of the text and the mysteries of its origins add to its aura of sanctity and make it one of the most exciting texts in the world (it is extremely common for Westerners to find the text simplistic and dull on first reading, and profound and moving after many readings). [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/]

“Confucius is sometimes pictured in conversation with various powerful patricians in his home state of Lu and elsewhere, but most often with his students, who are generally believed to have begun to compile this collection son after the Master’s death. Among the most famous of these disciples are the humble but brilliant Yan Yuan (or Yan Hui), the impetuous Zilu, the diplomat Zigong, and the scholarly Zixia. These aphorisms and snippets of conversation reflect the fresh but unsystematic teachings of the earliest Confucians. /+/

“The convention in citing the “Analects” is to record after each selection the number of the chapter and passage within the chapter of each isolated saying or story, and we will follow that convention here... It should be understood that whenever you read a phrase such as “Confucius said,” or “Confucius believed,” what is meant is that the Confucius we see in the “Analects” asserts these things. Whether the “historical” Confucius made precisely the same assertions is not possible to determine and, in any event, it is the Confucius of the “Analects” whose influence became so great.” /+/

“The following passages have been selected to illustrate both the main features of Confucius’s thought, and the texture of the “Analects” , which was among the most influential of all Classical texts. The point of many of these passages will seem straightforward, but in some cases you may wonder why they were worthy of being included in a book that carried such moral weight. It is precisely those passages, the ones that seem most superficial, which often most richly reward reflection. /+/

“Among the many translations of the “Analects” , well crafted versions by Arthur Waley (New York: 1938), D.C. Lau (Penguin Books, 1987, 1998), and Edward Slingerland (Indianapolis: 2003) are among the most accessible published. The “Analects” is a terse work with an exceptionally long and varied commentarial tradition; its richness and multiple levels of meaning make it a living document that reads differently to each generation (as true in China as elsewhere). Responsible interpreters vary in specific choices and overall understanding, and no single translation can be viewed as “definitive.”“ /+/

Translations of the Analects: 1) CHINATXT, Dr. Robert Eno’s Website The Analects of Confucius: An Online Teaching Translation (2015) scholarworks.iu.edu ; 2) Chinese Text Project version ctext.org/analects ; 3) MIT Classics classics.mit.edu

Good Websites and Sources on Confucianism: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Confucianism religioustolerance.org ; Religion Facts Confucianism Religion Facts ; Confucius .friesian.com ; Confucian Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Cult of Confucius /academics.hamilton.edu ; ; Virtual Temple tour drben.net/ChinaReport; Wikipedia article on Chinese religion Wikipedia Academic Info on Chinese religion academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Qufu Wikipedia Wikipedia Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIUS: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER, DISCIPLES AND SAYINGS factsanddetails.com; CHINA AT THE TIME CONFUCIANISM DEVELOPED factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY SOCIETY: FROM WHICH CONFUCIANISM EMERGED factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; NEO-CONFUCIANISM, WANG YANGMING, SIMA GUANG AND “CULTURAL CONFUCIANISM” factsanddetails.com; ZHU XI: THE INFLUENTIAL VOICE OF NEO-CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEXTS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM, GOVERNMENT AND EDUCATION factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AS A RELIGION factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEMPLES, SACRIFICES AND RITES factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND SOCIETY, FILIALITY AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM IN MODERN CHINA: CAMPS, FEEL GOOD CONFUCIANISM AND CONFUCIUS'S HEIRS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; ZHOU RELIGION AND RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com; DUKE OF ZHOU: CONFUCIUS'S HERO factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.): UPHEAVAL, CONFUCIUS AND THE AGE OF PHILOSOPHERS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM DURING THE EARLY HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Analects and Confucian Texts: Good translations of the “Analects” have been done by Arthur Waley (1938) Amazon.com; D.C. Lau (Penguin Books, 1987, 1998) Amazon.com; “The Analects” (Penguin Classics) by Confucius and Annping Chin Amazon.com; and Edward Slingerland (2003) Amazon.com. According to Dr. Robert Eno; “The “Analects” is a terse work with an exceptionally long and varied commentarial tradition; its richness and multiple levels of meaning make it a living document that reads differently to each generation (as true in China as elsewhere). Responsible interpreters vary in specific choices and overall understanding, and no single translation can be viewed as “definitive.” “The Four Books: The Basic Teachings of the Later Confucian Tradition” by Daniel K. Gardner Amazon.com; “The Complete Confucius: The Analects, The Doctrine Of The Mean, and The Great Learning” by Confucius and Nicholas Tamblyn Amazon.com; “The Four Chinese Classics: Tao Te Ching, Chuang Tzu, Analects, Mencius” by David Hinton Amazon.com

Analects on Li and Ren

Zhou ritual alter set

Li and ren are two important concepts in “The Analects”. Ren (or jen) is sort of an idealized view of humanity and sometimes translated as “humanness: or “humanity”). Li is often defined as “ritual. Dr. Eno wrote: “Heaven-ordained patterns constituted a complex set of social, political, and religious conventions and ceremonies known as Ritual (in Chinese, li). These rituals, which covered both everyday and ceremonial conduct were no longer properly practiced in the chaotic society of Confucius’s time and after (the Classical era)...Restoring these patterns of Chinese civilization was the practical path back to the ideal society. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/]

On li the Analects says: “1) The disciple Yan Yuan asked the Master about humanity (“ren”). The Master said, “Conquer yourself and return to “li”: that is goodness. If one could for a single day conquer oneself and return to “li”, the entire world would respond to him with goodness.... If it is not “li”, don't look at it; if it is not “li”, don't listen to it; if it is not “li”, don't say it; if it is not “li”, don't do it.” 2) The Master said, “When a ruler loves “li”, the people are easy to rule.” 3) The Master said, “Can ritual “li” and deference be employed to rule a state? Why, there is nothing to it!” 4) The disciple Zhonggong asked about “ren”. The Master said, “Whenever you go out your front gate continue to treat all you encounter as if they were great guests in your home. Whenever you direct the actions of others, do so as though you were officiating at a great sacrifice. And never act towards others in a way that you would not wish others to act towards you.” 5) Is “ren” distant? If I wish to be “ren” then “ren” is at hand.

“Lin Fang asked about what is fundamental in rites. The Master said, “This is indeed a great question. In rites, it is better to be sparing than to be excessive. In mourning, it is better to express grief than to emphasize formalities.” (3:4)“Sacrifice as if they were present” means to sacrifice to the spirits as if they were present. The Master said, “If I am not present at the sacrifice, it is as if there were no sacrifice.” (3:12) [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 45-50, 52, 54-55; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The disciple Master You said, “In the action of “li” harmony is the key. In the Dao of the former kings this was principle of greatest beauty. Affairs large and small all proceeded from this. Yet there was a limit. When one knew that a course of action would yield harmony but it was not according to “li”, one would not pursue it.” (1.12) The Master heard the Shao Music while in the state of Qi and for three months the succulent taste of meat dishes meant nothing to him. “I never imagined that music could reach this!” he said. (7.14) The Master said, “They talk of ritual, ritual: but is it just a matter of jades and silks! They talk of music, music: but is music just a matter of bells and drums!” (17.11) “If a man is not “ren”, how can he manage “li”? If a man is not “ren”, how can he manage music?” (3.3) Confucius referred to the use of the royal form of eight ranks of dancers by the Ji family of Lu. “If this can be tolerated, anything may be tolerated!” (3.1) /+/

On the virtue of “ren”, the Analects says: “The Master said, “To dwell amidst “ren” is the fairest course. If one chooses to dwell elsewhere, how can one become wise?” (4.1) “A person’s failings fall into certain categories. If you observe a person’s failings you may determine the degree to which he is “ren”.” (4.7) “Resoluteness and a wooden slowness of speech come close to “ren”.” (13.27) “When one is acting from “ren”, one does not yield to one’s teacher.” (15.36) “Is “ren” distant? If I wish to be “ren” then “ren” is at hand.” (7.30)

Analects on Junzi (Gentleman)

Dr. Eno wrote: “Confucius used various terms to describe the type of person who had internalized ritual behavior and become good. One of these terms reflects directly the social significance of Confucius’s thought for the patrician class. It is the term “”junzi””. Originally, “junzi” denoted a patrician: the basic meaning of the term is “ruler’s son.” It was thus a term describing one’s birth. Confucius, however, endowed the term with a strictly ethical dimension. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

According to The Analects: “If one removes “ren” from a “junzi”, then wherein is he worthy of the name? The “junzi” does not deviate from “ren” for an instant. Though he may be hurried or in dire straits, he always cleaves to “ren”.” (4.5) In this way, the criterion for qualifying as a “ruler’s son” is no longer that one be the son of a ruler, but rather that one accrue ethical accomplishments. Such a view contributed towards the formation of a political ideal of “meritocracy,” that is, the state where political power is allocated on the basis of merit. /+/

The Master said, “A “junzi” does not aim at stuffing himself when he eats, or at luxury in his home. He is quick about his affairs and careful in choosing his words. He cleaves to those who possess the Dao and rectifies himself by means of their example. Such a man may be said to be learned.” (1.14) “The “junzi” associates with others with broad impartiality and does not join cliques; a small man joins cliques and is not impartial.” (2.14) “The “junzi” values virtue; a small man values land. The “junzi” values the example men set; a small man values the favors they grant.” (4.11) “The “junzi” understands according to righteousness; a small man understands according to profit.” (4.16) “When a person’s plain qualities exceed his patterned behavior he is rude. When pattern exceeds plainness he is clerkish. When pattern and plainness are in perfect balance, that is a “junzi”!” (6.18) “The “junzi” seeks for it within himself; a small man seeks for it in others.” (15.21), The Master said, “To study and at due times to practice what one has studied, is this not pleasure! To have friends like oneself come from afar, is this not joy! To be unknown and remain unsoured, is this not a “junzi”!” /+/

Analects on Junzi and Social Obligations

Dr. Eno wrote: “Confucius modeled the qualities that the “junzi” would demonstrate in social action on an ideal picture of the ultimate “family man.” Society in Confucius’s time continued to be strongly oriented around lineage groups (the small extended family for the common people, huge clan descent groups for the upper patrician class). Confucius tended to view the state as a large scale version of the family, with the ruler representing “the father and mother of the people.” The “junzi” who could exemplify perfect political virtue then was one who was fully socialized into the domain of the family.For this reason, Confucius and his followers greatly stressed the importance of the traditional virtue of “filiality” (“xiao”), which means obedience and service to one’s parents, particularly to one’s father.” /+/

“The disciple Master You said, “The man who is filial and obedient to his elders will rarely be insubordinate to his superiors, and never has a man who was not insubordinate brought chaos to his state. The “junzi” applies himself to the roots of things, for once the roots are firm, the Way can grow. Filiality and obedience to elders are the roots of “ren”, are they not?” (1.2) This creates something of a paradox in the political ideal of the “junzi”. The “junzi” is to be a moral exemplar, leading all people towards a more virtuous society, yet he is also a follower, obeying his parents absolutely, as well as playing the junior role to all who are older than he.” /+/

Eno wrote: “For the Confucians, this was, in fact, no paradox. The absolute imperative of filial obedience was the fundamental means of broadening the self. Children are born with only self-regarding desires, born selfish. To acquire the fundamental skills that will allow one to view and treat others with as much regard as one does oneself, a long period of discipline must train the person to see the interests of others as his own. This is the function of filiality in Confucian thought. No man who was so selfish as to regard his own desires as more important than his parents’ could conceivably become a “junzi”, a man who must weigh the needs of his neighbors and even of his distant fellow countrymen as heavily as he does his own.” /+/

scene from the Classic of Filial Piety

Analects on Social Roles, and the Five Relationships

Dr. Eno wrote: “The concept of ritual “li” which was so central to early Confucianism did not imply that everyone who aspired to become a “junzi” must embark on memorization of endless action codes. Rather, “li” were thought of in terms of the responsibilities and forms that accompanied different social roles: the “li” of a filial child, the “li” of a clan elder, the “li” of a minister, and so forth. As a person moved through life, he or she would broaden control over “li” by mastering sets of responsibilities and forms that marked the assumption of emerging social roles. The individual was, in a sense, pictured almost exclusively in terms of the social roles that he or she had mastered and the characteristic style with which he or she had mastered (or failed to master) the basic structures of those roles. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Confucian texts did not speak of roles in the abstract. Instead, individuals were simply described and evaluated most regularly in terms of their roles and the state was described and evaluated in terms of the fit between role norms and actual social behavior. For example, in a famous passage of the “Analects” , Confucius pictures the ideal state as the perfect fulfillment of all role assignments: “Duke Jing of Qi asked Confucius about government. Confucius replied, “Let rulers be rulers, ministers ministers, fathers fathers, sons sons.” (12.11), The notion of social roles also provided Confucians with certain ways of adjudicating between competing commitments. For example, as the following passage makes clear, in the ideal state individuals privilege the role of the filial child over the role of the loyal subject: The Lord of She spoke to Confucius saying, “In my precincts there is an upright man. When his father stole a sheep, this man gave evidence against him.” “In my precinct the upright are different,” Confucius replied. “Fathers cover up for their sons and sons for their fathers. Uprightness lies therein.” (13.18) Furthermore, Confucians came to link the fulfillment of social role obligations with one’s legitimate claim to a role and its title. For example, rulers who did not act in accord with the normative (value.positive) features of the ruler’s role description were not actually entitled to the designation “ruler” at all.

“In extreme cases, this could license the deposing of a ruler, very much in harmony with the ethical implications of the Mandate of Heaven doctrine. This feature of Confucian role ethics came to be known as the doctrine of the “Rectification of Names” (a term that took on other meanings later). It is only suggested in the “Analects” , but seems to lie behind passages such as this one: “Duke Ding of Lu asked how a ruler should employ ministers and ministers should serve rulers. Confucius replied, “If the ruler employs his ministers according to “li”, the ministers will serve the ruler with loyalty.” (3.19) The notion of making the obligations of one role contingent on the proper performance of another did not apply to “natural” roles, such as the child’s. Filial duties were absolute.” “ /+/

“Eventually, Confucians brought together many of these ideas in a doctrine known as the “Five Relationships.” In it, all social roles were conceived as existing in essential polarity with some other complementary role, in the manner that the role of child is intrinsically defined as a complement to the role of parent. Confucians held that the myriad actual roles through which we live our social lives could ultimately be seen as variants on five paradigmatic polar relations, which may be listed as follows (the traditional version is on the left, a more universalized modern version on the right): Father / Son “Parent / Child”Elder Brother / Younger Brother “Senior / Junior”Ruler / Minister “Superior / Inferior”Husband / Wife “Spouse / Spouse”Friend / Friend “Friend / Friend”. The first three of these were viewed as intrinsically hierarchical and they are the relationships that attracted the most interest in the Confucian scheme. The last two were seen as egalitarian in theory (although the marriage relationship was clearly not so in practice). The Five Relationships can be understood as a way to bring coherence to the ideal of a completely ritualized society, and to give individuals an important conceptual tool in allowing them to pursue self-ritualization in the context of everyday social life.” /+/

On Women and Servants the Analects says: “Women and servants are most difficult to nurture. If one is close to them, they lose their reserve, while if one is distant, they feel resentful.” (17:25)

scene from the Classic of Filial Piety

Analects on Filiality

As we said before, reason, Confucius and his followers greatly stressed the importance of the traditional virtue of “filiality” (“xiao”), which means obedience and service to one’s parents, particularly to one’s father. According to “Analects”: “ Master You [You Ruo] said, “Among those who are filial toward their parents and fraternal toward their brothers, those who are inclined to offend against their superiors are few indeed. Among those who are disinclined to offend against their superiors, there have never been any who are yet inclined to create disorder. The noble person concerns himself with the root; when the root is established, the Way is born. Being filial and fraternal — is this not the root of humaneness?” (1:2) The Master said, “Those who are clever in their words and pretentious in their appearance, yet are humane, are few indeed.” (1:3) Ziyou asked about filial devotion. The Master said, “Nowadays filial devotion means being able to provide nourishment. But dogs and horses too can provide nourishment. “Unless one is reverent, where is the difference?” (2:7). [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 45-50, 52, 54-55; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Other selections from the “Analects on filial piety: 1) The Master said, “When a person’s father is alive, observe his intentions. After his father is no more, observe his actions. If for three years he does not change his father’s ways he is worthy to be called filial.”, 2) The disciple Master You said, “The man who is filial and obedient to his elders will rarely be insubordinate to his superiors, and never has a man who was not insubordinate brought chaos to his state. The “junzi” applies himself to the roots of things, for once the roots are firm, the Way can grow. Filiality and obedience to elders are the roots of “ren”, are they not?”

3) The Lord of She spoke to Confucius saying, “In my precincts there is an upright man. When his father stole a sheep, this man gave evidence against him.” “In my precinct the upright are different,” Confucius replied. “Fathers cover up for their sons and sons for their fathers. Uprightness lies therein.” 4) The disciple Ziyou asked about filiality. The Master said, “Those who speak of filiality nowadays mean by it merely supplying food and shelter to aged parents. Even dogs and horses receive as much. Without attentive respect, where is the difference?” 5) The disciple Zixia asked about filiality. The Master said, “It is the outward demeanor that it difficult to maintain! That the youngest shall bear the burden at work or that the elders shall be served first of food and drink, is this all that filiality means?”

“The patrician Meng Yizi asked about filiality. The Master said, “Never disobey!” Later, the disciple Fan Chi was driving the Master in his chariot and the Master said to him, “Meng Yizi asked me about filiality and I answered, ‘Never disobey!’” “What did you mean by that,” asked Fan Chi. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Master replied, “In life, serve parents according to “li”. In death, inter them according to “li” and sacrifice to them according to “li”.” (2.5) The patrician Meng Wubo asked about filiality. The Master said, “One’s parents should need to worry only about one’s health.” (2.6) The disciple Ziyou asked about filiality. The Master said, “Those who speak of filiality nowadays mean by it merely supplying food and shelter to aged parents. Even dogs and horses receive as much. Without attentive respect, where is the difference?” (2.7) The disciple Zixia asked about filiality. The Master said, “It is the outward demeanor that it difficult to maintain! That the youngest shall bear the burden at work or that the elders shall be served first of food and drink, is this all that filiality means?” (2.8)

scene from the Classic of Filial Piety

Analects on Humaneness (Ren)

The excerpts from the Analects presented below are specifically concerned with Confucius’ ideas regarding the concepts of humaneness (ren or jen, also translated as “humanity”). According to the Analects: “ The Master said, “One who is not humane is able neither to abide for long in hardship nor to abide for long in joy. The humane find peace in humaneness; the knowing derive profit from humaneness.” (4:2) The Master said, “Wealth and honor are what people desire, but one should not abide in them if it cannot be done in accordance with the Way. Poverty and lowliness are what people dislike, but one should not avoid them if it cannot be done in accordance with the Way. (4:5) [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 48-50, 52, 56, 59, 61-62; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“If the noble person rejects humaneness, how can he fulfill that name? The noble person does not abandon humaneness for so much as the space of a meal. Even when hard-pressed he is bound to it, bound to it even in time of danger.” The Master said, “I have not seen one who loved humaneness, nor one who hated inhumanity. One who loved humaneness will value nothing more highly. One who hated inhumanity would be humane so as not to allow inhumanity to affect his person. Is there someone whose strength has for the space of a single day been devoted to humaneness? I have not seen one whose strength was insufficient. It may have happened, but I have not seen it.” (4:6 ) The Master said, “The wise take joy in water; the humane take joy in mountains. The wise are active; the humane are tranquil. The wise enjoy; the humane endure. (6:21)

Zigong said, “What would you say of someone who broadly benefited the people and was able to help everyone? Could he be called humane?” The Master said, “How would this be a matter of humaneness? Surely he would have to be a sage? Even Yao and Shun were concerned about such things. As for humaneness — you want to establish yourself; then help others to establish themselves. You want to develop yourself; then help others to develop themselves. Being able to recognize oneself in others, one is on the way to being humane.” (6:28) The Master said, “Is humaneness far away? If I want to be humane, then humaneness is here.” (7:29)

“Yan Yuan asked about humaneness. The Master said, “Through mastering oneself and returning to ritual one becomes humane. If for a single day one can master oneself and return to ritual, the whole world will return to humaneness. Does the practice of humaneness come from oneself or from others?” Yan Yuan said, “May I ask about the specifics of this?” The Master said, “Look at nothing contrary to ritual; listen to nothing contrary to ritual; say nothing contrary to ritual; do nothing contrary to ritual.” Yan Yuan said, “Though unintelligent, Hui requests leave to put these words into practice.” (12:1)

“Sima Niu asked about humaneness. The Master said, “The humane person is cautious in his speech.” Sima Niu said, “Cautious of speech! Is this what you mean by humaneness?” The Master said, “When doing it is so difficult, how can one be without caution in speaking about it?” (12:3) Fan Chi asked about humaneness. The Master said, “It is loving people.” He asked about wisdom. The Master said, “It is knowing people.” When Fan Chi did not understand, the Master said, “Raise the upright, put them over the crooked, and you should be able to cause the crooked to become upright. Zhonggong [Ran Yong] asked about humaneness. The Master said, “When going abroad, treat everyone as if you were receiving a great guest; when employing the people, do so as if assisting in a great sacrifice. What you do not want for yourself, do not do to others. There should be no resentment in the state, and no resentment in the family.” Zhonggong said “Though unintelligent, Yong requests leave to put these words into practice.” (12:2)

The Master said, “It does not happen that the dedicated officer and the humane person seek life if it means harming their humaneness. It does happen that they sacrifice their lives so as to complete their humaneness.” (15:8) Zizhang asked Confucius about humaneness. Confucius said, “One who would carry out the five everywhere under Heaven would be humane.” “ I beg to ask what they are.” (“Respect, liberality, trustworthiness, earnestness, and kindness. If you are respectful, you will have no regret; if you are liberal, you will win the multitude; if you are trustworthy, you will be trusted; if you are earnest, you will be effective; if you are kind, you will be able to influence others.” (17:6)

Analects on Self-Cultivation, Righteousness and Courage

Dr. Eno wrote: “ The rituals of the Zhou, which may or may not have existed in a codified form during Confucius’s lifetime, might have been extensive, but they surely did not provide rules for all of life’s situations. By "li", Confucius was referring to a body of court behavior, religious and community ceremonies, traditional forms of poetry, music, and dance, and norms of patrician etiquette equivalent to, perhaps, the modern rule that men should remove their hats when in an elevator with women present (like Zhou "li" in Confucius’s time, this is a rule often unknown or ignored by people living in a feminist era when few men wear hats).[Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Ren

“But Confucius seems to have viewed “li” not so much as a set of rules or forms that should be followed, but rather as a training ground to shape human character. Once the limited codes of “li” had been fully mastered by the individual, that person was not just someone who knew the rules, but someone who was “well bred,” who had manners and style, and who could act with independent ethical self-assurance. Thus “li” and “ren” were linked in Confucian teaching to two other virtues, righteousness and courage, which were pictured as the natural possessions of the fully trained ritual actor. The man who had mastered the Confucian syllabus was one who was not only accomplished in the human arts, but one whose ethical activism was entirely reliable. To such a man, personal rewards meant nothing other than an affirmation of his own moral worth as recognized by a moral world, and he would easily lay down his life in order to achieve a social end of greater value. /+/

According to the “Analects”: “The Master said, “To eat coarse greens and drink water, to crook one’s elbow for a pillow, joy also lies therein. If they are not got by righteous means, wealth and rank are to me like the floating clouds.” (7.16) “The attitude of the “junzi” towards the world is this: Have nothing you insist on doing, have nothing you refuse ever to do, simply range yourself always by what is right.” (4.10) To follow such a dictum in the midst of the amoral social chaos of the Warring States period would not be easy. Not only did righteousness frequently involve spurning personal gains that were the product of immoral conduct, but it could also mean risking the anger of warlord power holders. The ideal man needed courage as well as ethical assurance.

“To see what is right and not to do it is to lack courage.” (2.24) “The wise are not confused; the “ren” are not anxious; the courageous are not afraid.” (9.29) “The man of “ren” is inevitably courageous.” (14.4) The person who has developed his social personality so strongly as to be “ren” – who is capable of feeling the interests of others and of society as intimately as he feels his own – will appear courageous because he sees the value of his own life in terms of his service to the world of good people. /+/

“The virtues of righteousness and courage were adapted by Confucius from the prevailing patrician code of honor that pervaded the “shi” class of educated men and noble warriors. Indeed, much of the moral self-discipline that became associated with the Confucian school of ritualism can be traced to the training that patrician youths had always received to prepare them for valorous conduct in battle. (A passage from the works of the second great Confucian, Mencius, which we will analyze later, brings out this connection very clearly.) Confucius was at some pains to distinguish the type of social ideal he was promoting from the more commonplace values of the Warring States patrician elite. Thus the passage cited above (14.4) goes on to say: “The man of “ren” is inevitably courageous, but courageous men are not inevitably “ren”.” /+/

On self-cultivation, the Analects says: “The Master said, “Do not be anxious that others do not recognize your abilities, be anxious that you do not recognize others’.” (1.16) “When I walk in a group of three, my teachers are always there. I select what is good in my companions and follow it; I select what is not good and change it within me.” (7.22) “I have spent whole days without eating, whole nights without sleeping in order to ponder. It was useless – not like study!” (15.31) The Master ruled out four things: Have no set ideas, no absolute demands, no stubbornness, no self. (9.4).” /+/

Analects On Government

Confucius as an administrator

Short passages from the “Analects” on government: The Master said, “Governing by means of virtue one is like the North Star: it sits in its place and the other stars do reverence to it.” (2.1) “‘He took no action and all was ruled’; would this not describe the Emperor Shun? What action did he take? He honored himself and sat facing south, that is all.” (15.5) “Virtue is never lonely; it always attracts neighbors.” (4.25) The patrician Ji Kangzi asked, “How would one use persuasion to make one’s people respectful and loyal?” The Master replied, “Approach them with seriousness and they will be respectful. Be filial towards your own parents and loving towards your children and the people will be loyal. Raise the good to positions of responsibility and instruct those who do not have abilities and they will be persuaded.” (2.20) The Master said, “I am no better than another at passing judgment in disputes of law. What is needed is to end the need for lawsuits.” (12.13) [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The patrician Ji Kangzi was troubled by banditry and asked Confucius about it. Confucius replied, “If you yourself were without desires others would not steal though you paid them to.” (12.18) Ji Kangzi questioned Confucius about governing. “How would it be if I executed the immoral so as to push others towards the good?” Confucius replied, “What need is there for executions in governance? If you yourself wish to be good, the people will be good. The virtue of the “junzi” is like wind and that of the people like grass. When the wind blows over the grass, it bends.” (12.19) The Master said, “Not to instruct the people in warfare is to throw them away.” (13.30) The Master said, “In ruling a state of a thousand chariots, one is reverent in the handling of affairs and shows himself to be trustworthy. One is economical in expenditures loves the people, and uses them only at the proper season.” (1:5).

“Zigong asked about government. The Master said, “Sufficient food, sufficient military force, the confidence of the people.” Zigong said, “If one had, unavoidably, to dispense with one of these three, which of them should go first?” The Master said, “Get rid of the military.” Zigong said, “If one had, unavoidably, to dispense with one of the remaining two which should go first?” The Master said, “Dispense with the food. Since ancient times there has always been death, but without confidence a people cannot stand.” Ji Kang Zi asked Confucius about government, saying, “How would it be if one killed those who do not possess the Way in order to benefit those who do possess it?” Confucius replied, “Sir, in conducting your government, why use killing? If you, sir, want goodness, the people will be good. The virtue of the noble person is like the wind, and the virtue of small people is like grass. When the wind blows over the grass, the grass must bend.” (12:7)

Analects On Rulers and Leadership

According to the “Analects”: “Duke Jing of Qi asked Confucius about government. Confucius replied, “Let the ruler be a ruler; the minister, a minister; the father, a father; the son, a son.” “Excellent,” said the duke. “Truly, if the ruler is not a ruler, the subject is not a subject, the father is not a father, and the son is not a son, though I have grain, will I get to eat it?” (12:11) Zilu asked how to serve a ruler. The Master said, “You may not deceive him, but you may stand up to him.” (14:23) [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 44-63; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The Master said, “If the noble person is not serious, he will not inspire awe, nor will his learning be sound. One should abide in loyalty and trustworthiness and should have no friends who are not his equal. If one has faults, one should not be afraid to change.” (1:8 ) The Master said, “Lead them by means of regulations and keep order among them through punishments, and the people will evade them and will lack any sense of shame. Lead them through moral force (de) and keep order among them through rites (li), and they will have a sense of shame and will also correct themselves.” (3:19) Duke Ding asked how a ruler should employ his ministers and how ministers should serve their ruler. Confucius replied, “The ruler should employ the ministers according to ritual; the ministers should serve the ruler with loyalty.” (3:19) [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 45-50, 52, 54-55; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Analects on Ideal Government

Dai Jin (King Wen of the Zhou Dynasty) Dropping a Line in the Wei River

According to the Analects 11:25: “Zilu, Zeng Xi, Ran You, and Gongxi Hua were seated in attendance. The Master said, “Never mind that I am a day older than you. Often you say, ‘I am not recognized.’ If you were to be recognized, what would you do?” Zilu hastily replied, “In a state of a thousand chariots, hemmed in by great states, beset by invading armies, and afflicted by famine — You [referring to himself] if allowed to govern for the space of three years, could cause the people to have courage and to know their direction.” The Master smiled. [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 44-63; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

““Qiu, what about you?” He replied, “In a state of sixty or seventy li [about one-third of a mile] square, or even fifty or sixty — Qiu, [Referring to himself] if allowed to govern for three years, could enable the people to have a sufficient livelihood. As for ritual and music, however, I should have to wait for a noble person.” “Chi [Referring to Gongxi Hua], what about you?” He replied, “I do not say that I am capable of this, yet I should like to learn it. At ceremonies in the ancestral temple and at the audiences of the lords at court, I should like, dressed in the dark robe and black cap, to serve as a minor assistant.” “Dian [referring to Zeng Xi or Zeng Dian], what about you?” As he paused in his playing the qin [a five-stringed musical instrument, such as a zither] and put the instrument aside, he replied, “My wish differs from what these three have chosen.” The Master said, “What harm is there in that? Each may speak his wish.” He said, “At the end of spring, when the spring clothes have been made, I should like to go with five or six youths who have assumed the cap, and with six or seven young boys, to bathe in the River Yi, to enjoy the breeze among the rain altars, and to return home singing.” The Master sighed deeply and said, “I am with Dian.”

“When the other three went out Zeng Xi remained behind and said, “What did you think of the words of the others?” The Master said, “Each one spoke his wish, that is all.” “Why did the Master smile at You?” “One governs a state through ritual, and his words reflected no sense of yielding. This is why I smiled.” “Was it not a state that Qiu wanted for himself?” “Yes, could one ever see a territory of sixty or seventy li, or of fifty or sixty li, that was not a state?” “And was it not a state that Chi wanted for himself?” “Yes, is there anyone besides the lords who frequent the ancestral temple and the audiences at court? If Chi were to play a minor role, who would play a major one?”

Analects 13:3: “Zilu said, “The ruler of Wei has been waiting for the Master to administer his government. What should come first?” The Master said, “What is necessary is the rectification of names.” Zilu said, “Could this be so? The Master is wide of the mark. Why should there be this rectification?” The Master said, “How uncultivated, You! In regard to what he does not know, the noble person is cautiously reserved. If names are not rectified, then language will not be appropriate, and if language is not appropriate, affairs will not be successfully carried out. If affairs are not successfully carried out, rites and music will not flourish, and if rites and music do not flourish, punishments will not hit the mark. If punishments do not hit the mark, the people will have nowhere to put hand or foot. Therefore the names used by the noble person must be appropriate for speech, and his speech must be appropriate for action. In regard to language, the noble person allows no carelessness, that is all.”

The Analects on Heaven and the World of Spirits

The Analects said: Jilu asked about serving spiritual beings. The Master said, “Before you have learned to serve human beings, how can you serve spirits?” “I venture to ask about death.” (“When you do not yet know life, how can you know about death?” (11:11) “The disciple Zilu asked about serving ghosts and spirits. “You do not yet know how to serve people,” replied the Master. “Why ask about serving the ghosts?” Zilu asked about death. The Master said, “When you do not yet know life, why seek to know death?” (11.12). Offer sacrifices as though the spirits were present. The Master said, “If I do not participate in the sacrifice it is the same as not sacrificing.” (3.12)

The Master said, “I wish never to speak!” The disciple Zigong said, “If you were never to speak, what would we have to pass on?” The Master said, “Does Heaven speak? Yet the four seasons turn and the things of the world grow. Does Heaven speak?” (17.19) The Master fell ill and Zilu asked leave to offer prayers. The Master said, “Is this permitted?” “Yes,” replied Zilu. “The liturgy in one place reads, ‘You may pray to the spirits above and below.’” The Master said, “I have been praying for a very long time.” (7.35)

[The Zhou Dynasty founder] King Wen is dead, but his patterns live on here in me, do they not? If Heaven wished these patterns to perish, I would not have been able to partake of them! Zilu asked about death. The Master said, “When you do not yet know life, why seek to know death?”...The Master said, “I wish never to speak!” The disciple Zigong said, “If you were never to speak, what would we have to pass on?” The Master said, “Does Heaven speak? Yet the four seasons turn and the things of the world grow. Does Heaven speak?”

Analects on The Dao

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Perhaps the greatest of Confucius’s social innovations was his invention of the role of professional teacher. He appears to have lived most of his life by means of the “tuition” which his students supplied. (Since some of these were prominent while others very poor, there was probably no set fee, just the expectation that the “master” would be properly honored by the sacrifice each student made.) While we may presume that patricians had long had adept men in their entourages who were expected to train the sons of the lord in the arts of their class, Confucius seems to have been the first man to offer to accept students of all classes. “I have never refused to teach any who offered as much as a bundle of dried sausages.” (7.7) [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Moreover, Confucius, not his “employer,” was in charge of the curriculum he offered. Confucius’s teaching was not simply a variety of the human arts and skills of the day, it was holistic syllabus, which he believed represented the unified cultural vision of the former sage kings. “I have a teaching; it is not divided into subjects.” (15.39). This unified curriculum Confucius called his “Dao,” a word that originally denoted a path or a method, and which we often translate as “Way” to include both these senses. Confucius saw his Dao as a path to personal and social perfection which had been discovered and passed down over the centuries, and which, once mastered, generated in individuals an all.encompassing form of knowing and skill. /+/

Confucius disciple Yan Yuan

Short passages from the “Analects” on The Dao: The Master said to Zeng Shen, “Shen! My Dao links all on a single thread.” Master Zeng replied, “So it does.” When the Master had gone, the other followers asked, “What did he mean?” Master Zeng replied, “The Master’s Dao is simply loyalty and reciprocity.” (4.15) The Master said, “A person can enlarge the Dao; the Dao does not enlarge a person.” (15.29) The Master said, “How grand was the rule of the [Sage King] Yao! Towering is the grandeur of Heaven; only Yao could emulate it. So grand that the people could find no words to describe it. Towering were his achievements! Glimmering, they formed a paradigm of pattern.” The Master said, “In the morning hear the Dao; in the evening die content.”

“The Master said to the disciple Zigong Si, “Si, do you take me to be one who has studied much and remembers it all?” “Yes,” replied Zigong. “Is it not so?” “It is not,” said the Master. “I link all upon a single thread.” (15.3) “In the morning hear the Dao; in the evening die content.” (4.8) The disciple Master Zeng said, “A true “shi” must be stalwart: his burden is heavy and his Way is long. To take “ren” as your personal task, is this not a heavy burden? To cease bearing it only after death, is not this Way long?” (8.7) In the West, because of the influence of Daoist single threphilosophy, which arose later than Confucianism and took the word “Dao” for its own, people who have encountered the term it often think of “the Dao” as something mystical or at least mysterious. Yet the evidence suggests that Confucius’s Dao was a straightforward combination of training in the arts of archery and charioteering, poetry citation and exegesis, ritual choreography, music, and dance. As his students mastered these various traditional skills, they were led to understand them both in terms of the Heaven-guided history of Chinese culture and in terms of their own destined roles as men of pattern in leading China towards a future perfection under a single sage ruler. Confucius’s vision was directed fully towards the worlds of history and society, and for him one needed to look nowhere but in the patterns of the ideal past to find the meaning of life. /+/

“The disciple Zigong said, “The insignia of pattern given to us by our Master is what we may know of him. As for what he may have said about human nature and the Dao of Heaven, that cannot be known.” (5.13) And to disciples who believed that Confucius had some secret knowledge or action that he was withholding from them in their ordinary studies, he replied “Do you gentlemen believe that I have something I am concealing from you? I have concealed nothing at all from you. I do nothing that I do not share with you. That is who I am.” (7.24) Still, there are some passages in the “Analects” which suggest a sense of mystery about Confucius’s teachings, such as the following remark attributed to Confucius’s finest disciple: Sighing deeply, Yan Yuan said, “The more I look up at it the higher it grows; the more I drill into it the harder it becomes – I glimpse it ahead and suddenly it is behind. How the Master lures us on step by step! He broadens me with pattern and constrains me with ritual. I long to give up but I cannot; yet it seems that all my abilities are exhausted. Still it is as if he stands so far above me that though I wish to follow after him, there is no path that reaches there.” (9.11)

Analects on Teaching and Learning

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The “Analects” is designed to illustrate for later generations the fulfillment that may be found in a life of ritual study, even if the outside world fails to offer recognition and rewards. The very first passage of the text sounds this theme. “The Master said, “To study and at due times to practice what one has studied, is this not pleasure! To have friends like oneself come from afar, is this not joy! To be unknown and remain unsoured, is this not a “junzi”!” (1.1) [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Short passages from the “Analects” on teaching and learning: “The Master said, “To learn without thinking is unavailing; to think without learning is dangerous.” (2:15) The Master said, “You [Zhong You, also known as Zilu, was known especially for his impetuousness], shall I teach you what knowledge is? When you know something, to know that you know it. When you do not know, to know that you do not know it. This is knowledge.” (2:17) “The Master said, “It is hard to find students who are willing to study for three years without taking a salaried post.” (8.12) [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 44-63; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The Master said, “Shen! In my Way there is one thing that runs throughout.” Zengzi said, “Yes.” When the Master had gone out the disciples asked, “What did he mean?” Zengzi said, “The Master’s Way is loyalty and reciprocity, that is all.” (4:15) The Master said, “The noble person is concerned with rightness; the small person is concerned with profit.” (4:16) Zigong said, “What I do not want others to do to me, I also want to refrain from doing to others.” The Master said, “Zi, this is not something to which you have attained.” (5:11) The Master said, “I transmit but do not create. In believing in and loving the ancients, I dare to compare myself with our old Peng.” [The identity of “our old Peng” is unclear, but he is usually taken to be the Chinese counterpart to Methuselah.] (7:1) The Master said, “From one who brought only a bundle of dried meat on up, I have never declined to give instruction to anyone.” [Dried meat, or other food, was offered as a present for teachers. Here it suggests the least one might offer] (7:7)

“The Master said, “To one who is not eager I do not reveal anything, nor do I explain anything to one who is not communicative. If I raise one corner for someone and he cannot come back with the other three, I do not go on.” (7:8) “The Master said, “Having coarse rice to eat, water to drink, a bent arm for a pillow.. joy lies in the midst of this as well. Wealth and honor that are not rightfully gained are to me as floating clouds.” (7:15) “The Duke of She asked Zilu about Confucius, and Zilu did not answer him. The Master said, “Why did you not simply say, ‘This is the sort of person he is: so stirred with devotion that he forgets to eat, so full of joy that he forgets to grieve, unconscious even of the approach of old age’?” (7:18) “The Master said, “Walking along with three people, my teacher is sure to be among them. I choose what is good in them and follow it and what is not good and change it.” (7:21) “There were four things the Master taught: culture, conduct, loyalty, and trustworthiness.” (7:24) The Master was mild and yet strict, dignified and yet not severe, courteous and yet at ease. (7:37) Four things the Master eschewed: he had no preconceptions, no prejudices, no obduracy, and no egotism. (9:4)

Confuciius and his students

“Yan Yuan, sighing deeply, said, “I look up to it and it is higher still; I delve into it and it is harder yet. I look for it in front, and suddenly it is behind. The Master skillfully leads a person step by step. He has broadened me with culture and restrained me with ritual. When I wish to give it up, I cannot do so. Having exerted all my ability, it is as if there were something standing up right before me, and though I want to follow it, there is no way to do so.” (9:10) The Master said, “A human being can enlarge the Way, but the Way cannot enlarge a human being.” (15:28) The Master said, “In education there should be no class distinctions.” (15:38) The Master said, “By nature close together; through practice set apart.” (17:2) [This simple observation attributed to Confucius was agreed upon as the essential truth with regard to human nature and racial difference by a group of international experts in the UNESCO “Statement on Race” published in July 1950.]

“Chang Ju and Jie Ni were working together tilling the fields. Confucius passed by them and sent Zilu to inquire about the ford. Chang Ju said, “Who is it who is holding the reins in the carriage?” Zilu said, “It is Kong Qiu.” “Would that be Kong Qiu of Lu?” “It would.” “In that case he already knows where the ford is.” Zilu then inquired of Jie Ni. Jie Ni said, “Who are you, sir?” “Zhong You.” “The follower of Kong Qiu of Lu?” “Yes.” “A rushing torrent.. such is the world. And who can change it? Rather than follow a scholar who withdraws from particular men, would it not be better to follow one who withdraws from the world?” He went on covering seed without stopping. Zilu went and told the Master, who sighed and said, “I cannot herd together with the birds and beasts. If I do not walk together with other human beings, with whom shall I associate? If the Way prevailed in the world, [I] Qiu would not be trying to change it.” (18:6)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei\=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016