CONFUCIANISM

This "Confucian symbol" is actually the word for "water" (shui), and doesn't have any special significance to Confucians

Confucianism is based on the family and an ideal model of relations between family members. It generalizes this family model to the state and to an international system — the Chinese world order. The principle is hierarchy within a reciprocal web of duties and obligations: the son obeys the father by following the dictates of filial piety; the father provides for and educates the son. Daughters obey mothers and mothers-in-law; younger siblings follow older siblings; wives are subordinate to husbands. The superior prestige and privileges of older adults make longevity a prime virtue. In the past, transgressors of these rules were regarded as uncultured beings unfit to be members of society. When generalized to politics, the principle mean that a village followed the leadership of venerated elders and citizens revered a king or emperor, who was thought of as the father of the state. Generalized to international affairs, the Chinese emperor was the big brother of the Korean king. [Source: Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1993]

The glue holding the traditional nobility together was education, meaning socialization into Confucian norms and virtues that began in early childhood with the reading of the Confucian classics. The model figure was the so-called true gentleman, the virtuous and learned scholar-official who was equally adept at poetry and statecraft. In Korea education started very early because Korean students had to master the extraordinarily difficult classical Chinese language — tens of thousands of written ideographs and their many meanings typically learned through rote memorization. Throughout the Chosun Dynasty, all official records and formal education and most written discourse were in classical Chinese. With Chinese language and philosophy came a profound cultural penetration of Korea, such that most Chosun arts and literature came to use Chinese models.

Confucianism is often thought to be a conservative philosophy, stressing tradition, veneration of a past golden age, careful attention to the performance of ritual, disdain for material goods, commerce, and the remaking of nature, combined with obedience to superiors and a preference for relatively frozen social hierarchies. Much commentary on contemporary Korea focuses on this legacy and, in particular, on its allegedly authoritarian, antidemocratic character. Emphasis on the legacy of Confucianism, however, does not explain the extraordinary commercial bustle of South Korea, the materialism and conspicuous consumption of new elites, or the determined struggles for democratization by Korean workers and students. At the same time, one cannot assume that communist North Korea broke completely with the past. The legacy of Confucianism includes the country's family-based politics, the succession to rule of the leader's son.

Confucian disciple Zilu

Confucianism was a system of ideas developed by later philosophers out of Confucius's thoughts and its relationship to the original thoughts of the man himself is extremely debatable. The term Confucianism was coined by Westerners. In China, Confucians call themselves ju, a word of uncertain origin that refers to their beliefs as the “way of the sages” or “the way of the ancients." These beliefs are associated with the legendary founders and ancient sages of China and are thought to have existed from time immemorial. Confucius is regarded as the last of the great sages.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Confucianism is perhaps the most well-known of the textual traditions in China. The classical Confucian texts became key to the orthodox state ideology of the Chinese dynasties, and these texts, though they were mastered only by a scholarly elite, in fact penetrated society deeply. Through the interpretation of the scholar Dong Zhongshu, who lived during the Han dynasty from around 179-104 B.C., Confucianism became strongly linked to the cosmic framework of traditional Chinese thought, as the Confucian ideals of ritual and social hierarchy came to be elaborated in terms of cosmic principles such as yin and yang. [Source: adapted from “The Spirits of Chinese Religion” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

Good Websites and Sources on Confucianism: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; Confucianism religioustolerance.org ; Religion Facts Confucianism Religion Facts ; Confucius .friesian.com ; Confucian Texts Chinese Text Project ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Cult of Confucius /academics.hamilton.edu ; ; Virtual Temple tour drben.net/ChinaReport; Wikipedia article on Chinese religion Wikipedia Academic Info on Chinese religion academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Qufu Wikipedia Wikipedia Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIUS: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER, DISCIPLES AND SAYINGS factsanddetails.com; CHINA AT THE TIME CONFUCIANISM DEVELOPED factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY SOCIETY: FROM WHICH CONFUCIANISM EMERGED factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; LATER HISTORY OF CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; NEO-CONFUCIANISM, WANG YANGMING, SIMA GUANG AND “CULTURAL CONFUCIANISM” factsanddetails.com; ZHU XI: THE INFLUENTIAL VOICE OF NEO-CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEXTS factsanddetails.com; ANALECTS OF CONFUCIUS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM, GOVERNMENT AND EDUCATION factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AS A RELIGION factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN TEMPLES, SACRIFICES AND RITES factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND SOCIETY, FILIALITY AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM IN MODERN CHINA: CAMPS, FEEL GOOD CONFUCIANISM AND CONFUCIUS'S HEIRS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; ZHOU RELIGION AND RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com; DUKE OF ZHOU: CONFUCIUS'S HERO factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.): UPHEAVAL, CONFUCIUS AND THE AGE OF PHILOSOPHERS factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM DURING THE EARLY HAN DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Confucianism “Confucianism: A Very Short Introduction” Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Confucianism” by Jennifer Oldstone-Moore Amazon.com; “The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About the Good Life” by Michael Puett, Christine Gross-Loh, et al. Amazon.com; “Confucius from the Heart” (popular Confucianism) by Yu Dan Amazon.com; Confucius, His Life and Time "Confucius, The Man and the Myth" by Herrlee Creel (1949, also published as "Confucius and the Chinese Way", a classic account of Confucius’s biography Amazon.com; "The Authentic Confucius: A Life in Thought and Politics" by Annping Chin, (New York: 2007) Amazon.com; “Lives of Confucius: Civilization's Greatest Sage Through the Ages” by Michael Nylan and Thomas Wilson Amazon.com; “Quotes of Confucius And Their Interpretations” by D. Brewer Amazon.com; “Philosophers of the Warring States: A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy” by Kurtis Hagen and Steve Coutinho Amazon.com ; Analects and Confucian Texts: Good translations of the “Analects” have been done by Arthur Waley (1938) Amazon.com; D.C. Lau (Penguin Books, 1987, 1998) Amazon.com; “The Analects” (Penguin Classics) by Confucius and Annping Chin Amazon.com; and Edward Slingerland (2003) Amazon.com. According to Dr. Robert Eno; “The “Analects” is a terse work with an exceptionally long and varied commentarial tradition; its richness and multiple levels of meaning make it a living document that reads differently to each generation (as true in China as elsewhere). Responsible interpreters vary in specific choices and overall understanding, and no single translation can be viewed as “definitive.” “The Four Books: The Basic Teachings of the Later Confucian Tradition” by Daniel K. Gardner Amazon.com; The Complete Confucius: The Analects, The Doctrine Of The Mean, and The Great Learning with an Introduction by Nicholas Ta... “The Complete Confucius: The Analects, The Doctrine Of The Mean, and The Great Learning” by Confucius and Nicholas Tamblyn Amazon.com; “The Four Chinese Classics: Tao Te Ching, Chuang Tzu, Analects, Mencius” by David Hinton Amazon.com; Neo-Confucianism: “Instructions for Practical Living: And Other Neo-Confucian Writings” by Wang Yang-Ming by Yangming Wang and Wing-tsit Chan Amazon.com; “Neo-Confucianism: Metaphysics, Mind, and Morality” by JeeLoo Liu Amazon.com; “Neo-Confucianism in History” (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Peter K. Bol Amazon.com

Is Confucianism a Religion?

Analects, Lun Yu Rongo

Although sometimes characterized as a religion Confucianism is more of a social and political philosophy than a religion. Some have called it code of conduct for gentlemen and way of life that has had a strong influence on Chinese thought, relationships and family rituals. Confucianism stresses harmony of relationships that are hierarchical yet provide benefits to both superior and inferior, a thought deemed useful and advantageous to Chinese authoritarian rulers of all times for its careful preservation of the class system.

There are two components of Confucianism: the earlier Rujia (Confucian school of philosophy) and the later Kongjiao (Confucian religion). The Rujia represents a political-philosophical tradition which was extremely important in imperialist times, and is the element most directly connected with the persons and teachings of Confucius and Mencius — Kong Meng zhi dao (the doctrine of Confucius and Mencius). The Kongjiao represents the state's efforts to meet the religious needs of the people within the framework of the Confucian tradition, an unsuccessful attempt which occurred in the late imperial period (960-1911 A.D.). [Source: “Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia”, Haeberle, Erwin J., Bullough, Vern L. and Bonnie Bullough, eds., sexarchive.info

Joseph Adler of Kenyon University College said: “Whether or not Confucianism is a religion (or a religious tradition, as I prefer to say) is highly contested by scholars. There are two recent books on the subject: Anna Sun, Confucianism As a World Religion: Contested Histories and Contemporary Realities (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013), and Yong Chen, Confucianism as Religion: Controversies and Consequences (Leiden: Brill, 2013). Also, I have an article on the subject kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion

The Library of Congress says: “Confucianism is not a religion, although some have tried to imbue it with rituals and religious qualities, but rather a philosophy and system of ethical conduct that since the fifth century B.C. has guided China's society. Kong Fuzi (Confucius in Latinized form) is honored in China as a great sage of antiquity whose writings promoted peace and harmony and good morals in family life and society in general. Ritualized reverence for one's ancestors, sometimes referred to as ancestor worship, has been a tradition in China since at least the Shang Dynasty (1750-1040 B.C.). [Source: Library of Congress]

Confucianism mainly addresses humanist concerns rather than things like God, revelation and the afterlife. It emphasizes tradition, respect for the elderly, hierarchal social order and rule by a benevolent leader who is supposed to look out for the well being of his people. Named after a Chinese sage named Confucius, it contains elements of ancestor worship, which is partly why it is sometime regarded as a religion. Traditionally, Chinese who have sought a mystical philosophy or religion turned to Taoism or Buddhism. This means that it is possible and even likely that someone who is regarded as a Confucian is also a Buddhist or a Taoist or even a Christian.

Confucius and the Origins of Confucianism

Confucius

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Textual records of systematic thought first emerge in China during the era of the Warring States. The earliest of these appear to be the records of Confucius’s saying that were gradually compiled by his disciples during the fifth century B.C., and then expanded by second and third generation disciples in subsequent years. Once the Confucians established the genre of recorded ideas, other people began to espouse different notions and their disciples emulated Confucius’s in recording them. By the end of the fourth century, this process has moved a step further, and individuals had begun to record their ideas directly in writings. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt chinatxt /+/ ]

“The variety of philosophies developed during this period was such that they are often referred to as the “Hundred Schools.” The word “schools” does not imply fixed buildings, but traditions associated with master.disciple lineages. The way in which philosophies were propagated seems generally to have been by groups of men who studied for many years with a master whose teachings they adopted and preached with energy, though over time generations of disciples would elaborate the teachings of their school in new ways, these changes sometimes leading to long-term divisions within traditions tracing back to a single master. /+/

“The interests of early Chinese philosophy were far more practical than were those of the earliest systematic Western thinkers, the Greeks. Whereas Greek thought seems to have begun with highly theoretical inquiries concerning Nature, Chinese thought begins with a social problem connected with Warring States political chaos. The central issue for Chinese thinkers was, how did China fall into this state of chaos, how can it get out of it, and what is the proper conduct for individuals in times such as these? These are the background issues behind the thought of Confucius, who may be seen as the founder of Chinese philosophy. Confucius lived at the close of the Spring and Autumn period (551-479 B.C.) and his mode of free inquiry is a model for the subsequent Warring States era. It is difficult to overstate Confucius’s importance to the cultural history of China. His particular school of thought is generally seen as having dominated Chinese society for two millennia (although some interpreters would say that it became pervasive only after having been adapted beyond recognition to the contours of China’s post-Classical imperial state). But even more important, Confucius made a decisive contribution in exemplifying the notion that the socio.political issues of his time were ones that needed to be resolved by thought and training rather than by diplomatic and military intrigue. Thus the path to China’s future was one that could be created by men of any social class regardless of their access to political prestige – not any man could occupy a throne or command an army, but any man could think and equip himself with ethical skills. In this sense, Confucius, by making study and thought a path to social recognition and political influence, reinforced the social trends that were moving China away from the closed society of the patrician state.

Key Ideas of Confucianism

Li symbol

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: What emerges “from the earliest layers of the written record is that Kong Qiu [Conficius] sought a revival of the ideas and institutions of a past golden age. Kong Qiu transmitted not only specific rituals and values but also a hierarchical social structure and the weight of the past. Employed in a minor government position as a specialist in the governmental and family rituals of his native state, Kong Qiu hoped to disseminate knowledge of the rites and inspire their universal performance. [Source: adapted from “The Spirits of Chinese Religion” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

“The Ideal Ruler. That kind of broad-scale transformation could take place, he thought, only with the active encouragement of responsible rulers. The ideal ruler, as exemplified by the legendary sage-kings Yao and Shun or the adviser to the Zhou rulers, the Duke of Zhou, exercises ethical suasion, the ability to influence others by the power of his moral example. To the virtues of the ruler correspond values that each individual is supposed to cultivate: 1) benevolence toward others; 2) a general sense of doing what is right; and 3) loyalty and diligence in serving one’s superiors.

“Ritual (Li). Universal moral ideals are necessary but not sufficient conditions for the restoration of civilization. Society also needs what Kong Qiu calls li, roughly translated as “ritual.” Although people are supposed to develop propriety or the ability to act appropriately in any given social situation (another sense of the same word, li), still the specific rituals people are supposed to perform (also li) vary considerably, depending on age, social status, gender, and context. In family ritual, for instance, rites of mourning depend on one’s kinship relation to the deceased. In international affairs, degrees of pomp, as measured by ornateness of dress and opulence of gifts, depend on the rank of the foreign emissary. Offerings to the gods are also highly regulated: the sacrifices of each social class are restricted to specific classes of deities, and a clear hierarchy prevails.”

Confucius's Teachings

Confucius talked about goodness and morality. He argued for a return to a mythical state of social harmony that existed in the past through filial and ceremonial piety, reverence towards authority and harmony with thought and consciousness. While his ideas weren't original, they caught on because they were packaged in such a way that people could understand, embrace and follow them. Confucius urged people to think for themselves and stand up for what the thought was right. He told his disciples, “If I feel in my heart that I am wrong, I must stand in fear even though my opponent is the least formidable of men. But if my own heart tells me that I am right, I shall go forward even against thousands and tens of thousands."

diorama of traditional Confucian view of teacher and student

Many fables about Confucius have a political message. Once Confucius and his disciplines came across a woman crying at a recently dug grave. When asked why she was crying the woman said, "My husband's father was killed here by a tiger, and my husband also, and now my son have met the same fate." When asked why she didn't want to leave the spot, she answered, "At least here there is no oppressive government." "Remember this my children, Confucius said, "oppressive government is fiercer and more feared that a tiger."

Dr. Eno wrote: “Despite being a man of no consequence to the patrician order, Confucius seems to have attracted the attention of high ranking patricians because of his original ideas and because he developed a particular mode of training which he offered, for a fee, to any who cared to undertake it. It seems that from his youth, Confucius had been attracted to the cultural trappings of Zhou Dynasty social arts: court poetry and music, refined martial arts training, and the ritual codes that were prescribed for use in clan and state temples and at court. Such forms had come to be known as the “”li””, or “rituals,” of the Zhou. He became, through self-training, a master of these, and he offered himself as a tutor for young men of promise – his instruction was, perhaps, initially comparable to that of a “finishing school,” imparting to patrician sons a polish in court behavior and etiquette that would allow them to make the most of their social and political opportunities during an era when “talent” was beginning to compete with pedigree as a criterion for social advancement. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Confucius, however, saw the training he offered as something far more than a social veneer. His interest in the ritual forms of the Zhou was based in his conviction that these were the expression of a destined human evolution towards a type of species perfection; for him, “li” were the flower of the human past and the blueprint for a future utopia. He believed that “li” offered the solution to all of China’s political problems, and he also saw in “li” the patterns which could elevate Chinese further and further above the animals (and non-Chinese “barbarians!”). “li” were the basis of human goodness and the path towards sagely perfection. /+/

“The great subtlety of early Confucianism derives from the fact that its core, ritual, initially appears to be merely a trivial concern with social polish but turns out to be – surprisingly – the basis of all human virtues, life skills, and sentiment. This is a role that Westerners often find puzzling: ritual and etiquette have rarely been a central concern to Western thinkers, and students of texts such as Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason”, for example, would not be inclined to substitute ritual for reason as the core of humanity. Nevertheless, during the late Classical period, Confucian ideas became increasingly significant in China, and Confucius is often thought of as the single most influential man in ancient China. /+/

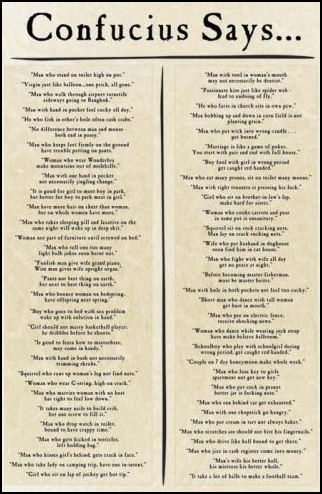

Famous Confucian Sayings

Confucian sayings were recorded in the Analects, which begin with the proverb: "Is it not a pleasure when friends visit from afar!" The sayings, aphorism, maxims, episodes and proverbs in the Analects were very useful in educating the illiterate masses. They were easy to remember and could be passed down orally from one generation to the next.

Confucian sayings were recorded in the Analects, which begin with the proverb: "Is it not a pleasure when friends visit from afar!" The sayings, aphorism, maxims, episodes and proverbs in the Analects were very useful in educating the illiterate masses. They were easy to remember and could be passed down orally from one generation to the next.

The most famous Confucian saying is Confucian version of the Golden Rule — "I wound not want to do to others what I do not want them to do to me" — which is much better put that Biblical and Talmudic proverbs that convey the same thought: "Therefore all things whatsoever ye would want men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law of the prophets" (Matthew 7:12); "What is hateful to you, do not to your fellow men. That is the entire Law; all the rest is commentary" (Shabbat, 31a).

Wisdom Confucius said was "when you know a thing, to recognize that you know it, and when you do not know a thing, to recognize that you do not know it...the mistakes of a gentleman may be compared to the eclipses of the sun or the moon. When he makes a mistake, all men see it; when he corrects it, all men look up to him...When you have faults do not fear to abandon them."

Confucius recognized the importance of the arts. "It is by poetry that one's mind is aroused; it is by ceremonials that one's character is regulated; it is by music that one becomes accomplished." On the nature versus nurture argument, Confucius said: "By nature, men are near alike; it is by custom and habit that they are set apart."

Many of the sayings convey a message of never-ending self improvement. "When walking with a party of three," Confucius said, "I always have teachers. I can select the good qualities of the one for imitation, and the bad ones of the other and correct them in myself." Some sayings are hard to figure out. One reads: “When the villagers were exorcizing evil spirits, he stood in his court robes on the eastern steps."

Lesser Confucian sayings include: 1) "Be not ashamed of misstates and thus make them crime." 2) "Ignorance is the night of the mind, but a night without moon and stars." 3) "It does not matter how slowly you go so long as you do not stop." 4) "Study without reflection is a waste of time; reflection without study is dangerous." 5) "He who rules by moral force is like the pole star, which remains in place while all the lesser stars do homage to it." 6) "Study the past if you would define the future."

Development of Confucianism and Confucian Thought

Dr. Eno wrote: “Confucius developed his ideas about the year 500 B.C. He was apparently well known to patricians in eastern China during his lifetime, but his thought initially had little influence outside his small group of immediate follows. As these men dispersed and took disciples of their own, however, Confucian thought became increasingly widespread. Not only did significant numbers of young men become trained in the ritual arts taught by Confucian masters, but the idealistic political rhetoric of Confucians, which drew heavily from early Zhou political traditions, took on a type of independent legitimacy. Somewhat as much of today’s rhetoric of “political correctness” is now routinely employed by people who have no firm political commitment, the rhetoric of Confucianism became important to political discourse despite the fact that virtually no Confucians seem to have been significant political actors during the Classical period. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“After Confucius’s death, two other great thinkers enlarged upon the Master’s ideas in significant ways. Mencius, who lived two centuries after Confucius, made major adjustments in Confucian philosophy, better equipping it to respond to assaults launched against it by newer styles of thought. He also stands as the only major Confucian ever to occupy high political position in a major state – albeit his days in power were few and unfortunate. Xunzi was the most brilliant of all ancient Confucian theoreticians. He lived a generation after Mencius, and wrote perhaps the most carefully conceived and argued set of essays in the Classical period. In this section, we will focus solely on the ideas of Confucius as reported by his later followers. We will consider Mencius and Xunzi later, in the context of Warring States intellectual trends.” /+/

“While prolonged study of Confucian thought leads to an appreciation of its originality, the overall framework in which that thought was expressed was explicitly conservative. Confucius’s prescription for the ailments of late Zhou China was based on a revivalist goal: Return to the ritual norms of early Zhou society; restore to the patrician lineages that were first granted patrimonial estates the actual power of rulership; revive the formulas for personal and political virtue established by the Zhou founders and expressed in the oldest Zhou texts. Actually, had all of Confucius’s conservative programs been adopted, the outcome would have been a very radical transformation of late Zhou society. Consequently, although Confucius himself seems to have claimed that all he was seeking was a readjustment of social relations to better accord with established norms, his thought actually represented a form of radical conservatism. This was apparently recognized by contemporary rulers, who rejected Confucius’s programs as too dangerous to their own established power.” /+/

Rise of Confucianism

The Legalist thinking prevailed after Emperor Qin unified China. Emperor Qin labeled Confucius a “subversive”; ordered that his books be burned; and executed anyone who dared to recite his texts. According to legend, Confucianism endured because some texts were hidden in a well. After Emperor Qin's death, Confucianism made a comeback.

During the Han dynasty (202 B.C. to A.D. 220), a period of great cultural, intellectual and political achievement, Confucianism was established as an essential element of the state. Confucians were first called on to clear up confusion over rites and ceremonies, and later they began educating the children in royal household as well as students at the Imperial University. Under Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.) Confucianism became the state orthodoxy, cultural philosophy, royal religion and state cult.

After that dynasties and emperors came and went but Confucianism endured. In the A.D. 7th and 8th century, Confucius began being worshiped like a religious figure in some places and temples were built to honor him. A Confucian revival was led by Han Yu (786-824).The invention of block printing during the Song dynasty (A.D. 960 to 1279) helped bring about a revival of Confucianism and popularized it to some degree among the masses as copies of the Analects and other writings were mass produced and found there way into the hands of ordinary people.The yearning for personal and social perfection evolved into a thoroughly complex collection of ethical ideals that bound the hearts, feet and minds of families, intellectuals and governors from Song through Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties (1644-1912).

Emergence of “Confucianism” During the Han Dynasty

Han Emperor Wu Di

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ It was only with the founding of the Han dynasty (202 B.C.-220 CE) that Confucianism became “Confucianism,” that the ideas associated with Kong Qiu’s name received state support and were disseminated generally throughout upper-class society. The creation of Confucianism was neither simple nor sudden, as the following three examples will make clear. [Source: adapted from “The Spirits of Chinese Religion” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbiaedu/]

“1) The Classical Texts. In the year 136 B.C. the classical writings touted by Confucian scholars were made the foundation of the official system of education and scholarship, to the exclusion of titles supported by other philosophers. The five classics (or five scriptures, wujing) were the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), Classic of History (Shujing), Classic of Changes (Yijing), Record of Rites (Liji), and Chronicles of the Spring and Autumn Period (Chunqiu) with the Zuo Commentary (Zuozhuan), most of which had existed prior to the time of Kong Qiu.Although Kong Qiu was commonly believed to have written or edited some of the five classics, his own statements (collected in the Analects [Lunyu]) and the writings of his closest followers were not yet admitted into the canon. [Note: The word jing denotes the warp threads in a piece of cloth. Once adopted as a generic term for the authoritative texts of Han-dynasty Confucianism, it was applied by other traditions to their sacred books. It is translated variously as book, classic, scripture, and sutra.]

“2. State Sponsorship. Kong Qiu’s name was implicated more directly in the second example of the Confucian system, the state-sponsored cult that erected temples in his honor throughout the empire and that provided monetary support for turning his ancestral home into a national shrine. Members of the literate elite visited such temples, paying formalized respect and enacting rituals in front of spirit tablets of the master and his disciples.

Dong zhonshu

“3. Dong Zhongshu’s Cosmological Framework. The third example is the corpus of writing left by the scholar Dong Zhongshu (ca. 179-104 B.C.), who was instrumental in promoting Confucian ideas and books in official circles. Dong was recognized by the government as the leading spokesman for the scholarly elite. His theories provided an overarching cosmological framework for Kong Qiu’s ideals, sometimes adding ideas unknown in Kong Qiu’s time, sometimes making more explicit or providing a particular interpretation of what was already stated in Kong Qiu’s work.

“Dong drew heavily on concepts of earlier thinkers — few of whom were self-avowed Confucians — to explain the workings of the cosmos. He used the concepts of yin and yang to explain how change followed a knowable pattern, and he elaborated on the role of the ruler as one who connected the realms of Heaven, Earth, and humans. The social hierarchy implicit in Kong Qiu’s ideal world was coterminous, thought Dong, with a division of all natural relationships into a superior and inferior member. Dong’s theories proved determinative for the political culture of Confucianism during the Han and later dynasties.

“What in all of the examples above, we need to ask, was Confucian? Or, more precisely, what kind of thing is the “Confucianism” in each of these examples? In the case of the five classics, “Confucianism” amounts to a set of books that were mostly written before Kong Qiu lived but that later tradition associates with his name. It is a curriculum instituted by the emperor for use in the most prestigious institutions of learning. In the case of the state cult, “Confucianism” is a complex ritual apparatus, an empire-wide network of shrines patronized by government authorities. It depends upon the ability of the government to maintain religious institutions throughout the empire and upon the willingness of state officials to engage regularly in worship. In the case of the work of Dong Zhongshu, “Confucianism” is a conceptual scheme, a fluid synthesis of some of Kong Qiu’s ideals and the various cosmologies popular well after Kong Qiu lived. Rather than being an updating of something universally acknowledged as Kong Qiu’s philosophy, it is a conscious systematizing, under the symbol of Kong Qiu, of ideas current in the Han dynasty.”

Confucian School of Thought and Learning

Dr. Eno wrote: “The Confucian School is represented in ancient philosophical writings by the teachings of three major thinkers and by a few other important texts that are by unknown authors. The three major thinkers are: Confucius (Kongzi, 551-479 B.C.), Mencius (Mengzi, c. 380-300 B.C.), Xunzi (c.310-230 B.C.). These men were all identified in Chinese as “Ru” ò, a term of uncertain origin and obscure meaning that ultimately came to denote people whom we now call “Confucians” in English. Whether there were Ru before Confucius is an issue that has not been settled. [Source: Robert Eno, /+/ ]

Mencius Temple

“The teachings of Confucius are conveyed to us through a collection of sayings by and about him and his immediate disciples. In English, this collection is called "The Analects of Confucius" (“analects” means “sayings”). The teachings of Mencius and Xunzi are collected in books that use the names of these two thinkers as book titles: we call them “The Mencius”and “Xunzi”. Among the anonymous Confucian texts of the ancient period, the ones we will discuss in this course include “The Great Learning”and “The Doctrine of the Mean”. This reading will describe some features common to all early Confucian texts, and then focus on Confucius and the “Analects” . /+/

“Confucianism was not only a “school” of thought; it was a school in the strict sense. During the Classical period, Confucianism was taught and learned in small teacher-study training groups. Young aristocrats whose fathers wanted them to deepen their grasp on Zhou cultural skills, non-aristocratic youths who wished to acquire the polish that might attract a ruler’s patronage and gain them a court appointment, and ethically ambitious young men of both classes were likely to seek out a master trained in the arts promoted by Confucius, present some form of tuition payment, and then “enroll” as a long- or short-term disciple, coming daily to the home of the master to receive with other students Confucius’s Dao. This was the model that Confucius himself established, as the first truly independent private teacher in China. After Confucius’s own death, many of his disciples became teachers and continued this pattern, which was then passed on generation after generation. /+/

“A very important aspect of Confucian teaching was the belief that the traditional forms of Zhou Dynasty society represented the cumulative Dao (“Way,” or teaching) of a series of sage rulers, and Confucian training groups conveyed to students both the ideas of major Confucian teachers and also the social arts that characterized traditional culture. Until recently, there existed throughout America a special type of school, called a “Finishing School,” that trained upper class young ladies in the social arts they would need to appear refined in wealthy society; Confucian training groups were, in part, a type of Finishing School for young men of the Warring States period who wished to be recognized as cultivated candidates for high social position. /+/

“The Finishing School aspect of Confucianism laid great stress on the importance of certain prized behaviors: filial devotion to parents, graceful deference towards elders, and thorough mastery of all features of etiquette and stylish elegance. These features, which we might be tempted to view as superficial, artificial, and priggish, were linked to a set of ethical teachings that demanded of students a rigorous commitment to self-transformation and moral excellence. Among the main ideas of these teachings were the notion that every person should nurture in himself a thorough devotion to the interests of others, a commitment to righteous action regardless of personal cost, the flexibility to fulfill any social role, no manner how demeaning, that could further the betterment of the world, and a willingness to suffer poverty and disgrace in the service of this ethical Dao. /+/

“The syllabus that Confucius and his followers taught included at least four elements, apart from the basic diet of ethical discussion that we see reflected in texts such as the “Analects” : Martial arts. We know from the “Analects” that, at least at the beginning, students were trained in arts such as archery and charioteering. Teaching these aristocratic skills of the warrior Zhou culture was consistent with the “Finishing School” side of Confucianism. /+/

Confucian Ritual and Artistry

Dr. Eno wrote: “Although we do not know precisely what ritual codes Confucius used, we know that his students and those of later generations of Confucian masters were drilled intensively in Zhou ritual codes. These included the ceremonies of major events, such as state sacrifices, court rituals, marriage and funeral rites, and so forth, and also the more everyday codes that governed private life. Students aspired to acquire through this training not only control of the vast ceremonial corpus of Zhou codes (which, for many, would become the economic basis of their professional lives as masters of ceremony at weddings and so forth), but also a stylish grace and certainty of social presence that would attract the respect and trust of people in society at large. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Zhou rituals represented the highest development of the human arts of the Classical era, and Confucian disciples studied these arts intensively. Ritual performance included musical elements, and disciples learned how to sing and harmonize, how to dance and choreograph lavish musical spectacles, and how to play musical instruments. So important were the elements of costume, music, and dance to Confucianism, that their enemies, the Mohists, claimed that the chief means by which Confucianism polluted the minds of the young was by attracting them through “chanting songs and beating out dance rhythms, and prancing about with wing-like gestures.”

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “If even during the Han dynasty the term “Confucianism” covers so many different sorts of things — books, a ritual apparatus, a conceptual scheme — one might well wonder why we persist in using one single word to cover such a broad range of phenomena. Sorting out the pieces of that puzzle is now one of the most pressing tasks in the study of Chinese history, which is already beginning to replace the wooden division of the Chinese intellectual world into the three teachings — each in turn marked by phases called “proto-,” “neo-,” or “revival of” —with a more critical and nuanced understanding of how traditions are made and sustained. [Source: adapted from “The Spirits of Chinese Religion” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbiaedu/]

“It is instructive to observe how the word “Confucianism” came to be applied to all of these things and more.(2) As a word, “Confucianism” is tied to the Latin name, “Confucius,” which originated not with Chinese philosophers but with European missionaries in the sixteenth century. Committed to winning over the top echelons of Chinese society, Jesuits and other Catholic orders subscribed to the version of Chinese religious history supplied to them by the educated elite. The story they told was that their teaching began with Kong Qiu, who was referred to as Kongfuzi, rendered into Latin as “Confucius.” It was elaborated by Mengzi (rendered as “Mencius”) and Xunzi and was given official recognition — as if it had existed as the same entity, unmodified for several hundred years — under the Han dynasty. The teaching changed to the status of an unachieved metaphysical principle during the centuries that Buddhism was believed to have been dominant and was resuscitated — still basically unchanged only with the teachings of Zhou Dunyi (1017- 1073), Zhang Zai (1020), Cheng Hao (1032-1085), and Cheng Yi (1033- 1107), and the commentaries authored by Zhu Xi (1130-1200). [Source: Note: For further details, see Lionel M. Jensen, “The Invention of ‘Confucius’ and His Chinese Other, ‘Kong Fuzi,’” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 1.2 (Fall 1993): 414-59; and Thomas A. Wilson, Genealogy of the Way: The Construction and Uses of the Confucian Tradition in Late Imperial China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995).]

Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism

Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism

Taoism (or Daoism in pinyin), the second most important stream of Chinese thought, also developed during the Zhou period. Its formulation is attributed to the legendary sage Lao Zi (Old Master), said to predate Confucius, and Zhuang Zi (369-286 B.C.). The focus of Taoism is the individual in nature rather than the individual in society. It holds that the goal of life for each individual is to find one's own personal adjustment to the rhythm of the natural (and supernatural) world, to follow the Way (dao) of the universe. In many ways the opposite of rigid Confucian moralism, Taoism served many of its adherents as a complement to their ordered daily lives. A scholar on duty as an official would usually follow Confucian teachings but at leisure or in retirement might seek harmony with nature as a Taoist recluse. [Source: The Library of Congress]

With competition from Taoism and Buddhism — beliefs that promised some kind of life after death — Confucianism became more like a religion under the Neo-Confucian leader Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi, A.D. 1130-1200). In an effort to win converts from Taoism and Buddhism, Zhu developed a more mystical form of Confucianism in which followers were encouraged to seek “all things under heaven beginning with known principals “and strive “to reach the uppermost." He told his followers, “After sufficient labor...the day will come when all things suddenly become clear and intelligible." Important concepts in Neo-Confucian thought were the idea of “breath “(the material from which all things condensed and dissolved) and yin and yang.

Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in Time, “A century ago, a broad spectrum of Chinese intellectuals criticized Confucianism for holding China back, and as recently as the 1970s, communist leaders were denouncing Confucius. China, moreover, has never been an exclusively Confucian nation. There have always been other indigenous, competing creeds. Taoism, for example, has provided an antiauthoritarian counterpoint to hierarchical models of politics for millennia. [Source: Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Time, January 1 2011]

Confucianism in the Imperial Era

Qing Emperor Yongzheng offering a sacrifice

Confucianism originated and developed as the ideology of professional administrators and continued to bear the impress of its origins. Imperial-era Confucianists concentrated on this world and had an agnostic attitude toward the supernatural. They approved of ritual and ceremony, but primarily for their supposed educational and psychological effects on those participating. Confucianists tended to regard religious specialists (who historically were often rivals for authority or imperial favor) as either misguided or intent on squeezing money from the credulous masses. The major metaphysical element in Confucian thought was the belief in an impersonal ultimate natural order that included the social order. Confucianists asserted that they understood the inherent pattern for social and political organization and therefore had the authority to run society and the state. [Source: Library of Congress *]

“The Confucianists claimed authority based on their knowledge, which came from direct mastery of a set of books. These books, the Confucian Classics, were thought to contain the distilled wisdom of the past and to apply to all human beings everywhere at all times. The mastery of the Classics was the highest form of education and the best possible qualification for holding public office. The way to achieve the ideal society was to teach the entire people as much of the content of the Classics as possible. It was assumed that everyone was educable and that everyone needed educating. The social order may have been natural, but it was not assumed to be instinctive. Confucianism put great stress on learning, study, and all aspects of socialization. Confucianists preferred internalized moral guidance to the external force of law, which they regarded as a punitive force applied to those unable to learn morality. *

Confucianists saw the ideal society as a hierarchy, in which everyone knew his or her proper place and duties. The existence of a ruler and of a state were taken for granted, but Confucianists held that rulers had to demonstrate their fitness to rule by their "merit." The essential point was that heredity was an insufficient qualification for legitimate authority. As practical administrators, Confucianists came to terms with hereditary kings and emperors but insisted on their right to educate rulers in the principles of Confucian thought. Traditional Chinese thought thus combined an ideally rigid and hierarchical social order with an appreciation for education, individual achievement, and mobility within the rigid structure. *

While ideally everyone would benefit from direct study of the Classics, this was not a realistic goal in a society composed largely of illiterate peasants. But Confucianists had a keen appreciation for the influence of social models and for the socializing and teaching functions of public rituals and ceremonies. The common people were thought to be influenced by the examples of their rulers and officials, as well as by public events. Vehicles of cultural transmission, such as folk songs, popular drama, and literature and the arts, were the objects of government and scholarly attention. Many scholars, even if they did not hold public office, put a great deal of effort into popularizing Confucian values by lecturing on morality, publicly praising local examples of proper conduct, and "reforming" local customs, such as bawdy harvest festivals. In this manner, over hundreds of years, the values of Confucianism were diffused across China and into scattered peasant villages and rural culture. *

Confucian Examination System

Exam cells

In late imperial China the status of local-level elites was ratified by contact with the central government, which maintained a monopoly on society's most prestigious titles. The examination system and associated methods of recruitment to the central bureaucracy were major mechanisms by which the central government captured and held the loyalty of local-level elites. Their loyalty, in turn, ensured the integration of the Chinese state and countered tendencies toward regional autonomy and the breakup of the centralized system. The examination system distributed its prizes according to provincial and prefectural quotas, which meant that imperial officials were recruited from the whole country, in numbers roughly proportional to a province's population. Elites all over China, even in the disadvantaged peripheral regions, had a chance at succeeding in the examinations and achieving the rewards of officeholding. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The examination system also served to maintain cultural unity and consensus on basic values. The uniformity of the content of the examinations meant that the local elite and ambitious would-be elite all across China were being indoctrinated with the same values. Even though only a small fraction (about 5 percent) of those who attempted the examinations passed them and received titles, the study, self-indoctrination, and hope of eventual success on a subsequent examination served to sustain the interest of those who took them. Those who failed to pass (most of the candidates at any single examination) did not lose wealth or local social standing; as dedicated believers in Confucian orthodoxy, they served, without the benefit of state appointments, as teachers, patrons of the arts, and managers of local projects, such as irrigation works, schools, or charitable foundations. *

In late traditional China, then, education was valued in part because of its possible payoff in the examination system. The overall result of the examination system and its associated study was cultural uniformity — identification of the educated with national rather than regional goals and values. This self-conscious national identity underlies the nationalism so important in China's politics in the twentieth century. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021