MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA

Linked Hybrid

China is becoming a focal point for cutting edge architecture. There are a lot of projects and development and a plentiful supply of cheap labor to build them. Constructions cost on China are about a tenth of what they are in the West and little as one 15th of what they are in New York and London.The famous Italian architect Mario Bellini told Reuters, “China is today a place to be...China is giving great architects really great opportunities at this moment, with financial power, a very fast decision process, and physically fast construction. In the time they build a tower there, we build a little house.”Some of the new buildings are quite bold or ridiculous depending on you perspective. One architect told the New York Times, “Everyone is encouraged to do their most stupid and extravagant designs there. They don’t have as much barrier between good taste and bad taste between minimal and expressive,.”

Some have compared China’s flamboyant new architecture with fashion show fashions — clothes are interesting to look at but you would never be caught wearing it on the street. Some Chinese complain the designs are for foreign tastes rather than Chinese ones. Du Xiaodong, editor of Chinese Heritage told National Geographic, “China is not confident in its own deigns and people prefer to try something new. The result are disconnected from whatever’s next door, and the newest building in the world sits next to some of the oldest, standing together like strangers.”

China’s low-wage workers allow foreign architects to design bold, innovative structures that would be too costly to build anywhere else. Some have described China as a “Western architects” weapons testing ground.”

Using massive construction crews that work around the clock with no union interference the building are constructed in incredibly short times, Even the most ambitious project can be finished in three or four years. Many of the buildings are designed to be built by low skilled workers at break neck speed. Many have prefabricated parts that can be snapped together rather than cut on site.

See Separate Articles: ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE ARCHITECTURE AND FAMOUS BUILDINGS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SKYSCRAPERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PUDONG AND SKYSCRAPERS AND FAST ELEVATORS IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; SHENZHEN: SKYSCRAPERS, MINIATURE CITIES AND CHINA’S FASTEST-GROWING AND WEALTHIEST CITY factsanddetails.com ; MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINAfactsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com. Edited by professors and graduate students from Columbia, Yale, and the University of Virginia, this site offers thousands of photographic images of Asia's diverse architectural heritage at hundreds of sites in 17 countries. Modern Architecture in China: Gluckman.com gluckman.com ; New York Times Interactive New York Times Beijing: Bird’s Nest Stadium Wikipedia Wikipedia Water Cube Wikipedia ; National Center for Performing Arts Websites China National Center for Performing Arts Official Site China National Center for Performing Arts ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Guardian Slide Show Guardian Slideshow ; Terminal 3 at the Beijing Airport Blog Report naseba08 ; Beijing Airport Beijing Airport site ; Wikipedia , Wikipedia ; CCTV Headquarters Websites < OMA Oma ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Shanghai: Oriental Pearl Tower in Shanghai Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Jin Mao Building in Shanghai Skyscraper Page Skyscraper Page ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Jin Mao Group Jin Mao Group ; Shanghai World Financial Center Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Shanghai World Financial Center official site Shanghai World Financial Center official site ; Skyscraper Page Skyscraper Page

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China Modern” by Sharon Leece and A. Chester Ong Amazon.com; “Designing Reform: Architecture in the People’s Republic of China, 1970–1992" by Cole Roskam Amazon.com; “Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China” by Peter G. Rowe and Seng Kuan Amazon.com; “Chinese Architecture: A History” by Nancy Steinhardt Amazon.com “Chinese Architecture” by Qijun Wang Amazon.com; “Chinese Architecture” by Fu Xinian, Guo Daiheng, et al. Amazon.com; “Houses of China” by Bonnie Shemie (1996) Amazon.com; “A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by David Wang Amazon.com

Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin, Pioneers of Modern Chinese Architecture and Preservation

Liang Sicheng (1901-1972) and his wife Lin Huiyin (1904-1955) are regarded as two of China's most revered architects, with Liang being known as the father of modern Chinese architecture. Their appreciation of China's ancient buildings and their devotion to preserving Beijing's heritage have made them highly respected by conservationist and architects today, but not so much so by the Chinese Communist Party. Their most important work was carried out while they were living in a courtyard house in Beizongbu Hutong in Beijing in the 1930s. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 30, 2012]

Shanghai Oriental Pearl Tower

Liang and Lin wrote seminal pieces on Chinese architecture and listed relics in need of protection during wartime. Liang and his colleague Chen Zhanxiang urged the Communist government to build an entirely new city when it decided to make Beijing the capital of the new republic. He believed it was the best way to preserve its ancient buildings. But officials rejected that plan and most of the old city has vanished forever.

Tania Branigan wrote in the The Guardian: , Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin are regarded by some as Beijing’s original preservationists. Liang wrote “The History of Chinese Architecture”. After the Communists came to power Liang and Lin helped design the new national emblem and were asked to invent a new style of Chinese architecture. Among Liang’s most famous designs is the Monument to the People’ Heroes that stands at the center of Tiananmen Square. In the end Liang’s ideas where incompatible with those of the Communists. Liang tried by persuade Mao Zedong to save Beijing’s towering walls, which encircles the capital. The request was rejected and the walls were torn down and replaced with a quasi ring road. In February 2012, under the cover of night and the Chinese New Year, a team armed only with hand tools demolished the sprawling 400-square-meter courtyard house at No. 24 Bei Zong Bu Alley, where Laing and his wife lived from 1930 to 1937, to make way for modern development.

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “The architect Liang Sicheng and his brilliant poet wife, Lin Huiyin” were a “prodigiously talented couple, who are now revered in much the same way as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Mexico” They “were part of a new generation of Western-educated thinkers who came of age in the 1920s. Born into aristocratic, progressive families, they had both studied at the University of Pennsylvania and other Ivy League schools in the United States, and had traveled widely in Europe. Since China’s embrace of capitalism in the 1980s, a growing number of Chinese are realizing the wisdom of Liang and Lin’s preservation message. As Beijing’s wretched pollution and traffic gridlock have reached world headlines, Liang’s 1950 plan to save the historic city has taken on a prophetic value. “I realize now how terrible it is for a person to be so far ahead of his time,” says Hu Jingcao, the Beijing filmmaker who directed the documentary Liang and Lin in 2010. “Liang saw things 50 years before everyone else. Now we say, Let’s plan our cities, let’s keep them beautiful! Let’s make them work for people, not just cars. But for him, the idea only led to frustration and suffering.” [Source: Tony Perrottet; Smithsonian Magazine, January 2017]

Persecution of Liang Sicheng During the Cultural Revolution

Lin died in 1955 after an illness. Liang was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and died in 1972. His second wife was named Lin Zhu. Branigan wrote:“When Liang Sicheng was denounced as a counter-revolutionary, he was scared to look even his wife in the eye. Lin Zhu, who had been working in the countryside at the time, rushed home to him on learning the news. "He said, 'I've been waiting for you and missing you every day, but I'm afraid to see you,'" she told The Guardian. Her husband sensed the horror ahead. Beijing's Tsinghua University — one of the country's top institutions — was already covered in posters attacking professors. Lin Zhu said, Back then, I thought this was like a dark cloud that would soon pass. I didn't realise it would cover the country for the next 10 years." When it lifted, Liang was dead, his health wrecked by the scores of lengthy "struggle sessions" publicly to humiliate him; by beatings from Red Guards; and by the cold, damp conditions of the building to which the family had been moved. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 24, 2012]

Lin still struggles to understand how hundreds of millions could participate in such cruelties. Some of Liang's persecutors were forced into taking part, she says; others were jealous of his success. Most were young students who did not understand his ideas. To her husband, who had loved teaching, that was particularly painful. "He wrote confession letters, one after another, but didn't know what he had done. The most important claim was that he had received a 'capitalist education'. No one could tell us what proletarian architectural design was — and you were too afraid to ask." As the movement escalated, Lin considered demands to join it: "I thought probably I would be beaten to death by the Red Guards. Maybe my children would desert me and my friends would keep their distance. But I couldn't understand what Liang Sicheng had done. I couldn't go against my conscience by leaving him."

Together they endured six years of enforced Maoist study and public denunciations that often ran for hours. "Because it was all day long, the brain sort of became numb," Lin recalls. "Normally he was not beaten up at those sessions, but sometimes they would come and beat us at home." Liang's ordeal ended when he grew so sick that he could no longer rise from his bed for the struggle sessions. He died in 1972, aged 70. In later years, Lin worked with her husband's accusers; some, quietly, apologised. She does not blame individuals for caving into pressure to attack others, though she is adamant that she never did so. She even suggests those years helped her to grow. "Whatever happens, whatever comes, I'm not afraid any more. It made me stronger and made me think," she says. But she fears that intellectual life in China has never fully recovered — and she worries the country could see another such movement. "Many of us are concerned about whether we can avoid a similar disaster in future. History doesn't repeat itself exactly — but it's possible."

I.M. Pei

I.M. Pei is one of the world's most famous architects. A Chinese-American, he was born in Guangzhou, grew up in Hong Kong and Shanghai and graduated from M.I.T. and later studied under Barhaus-founder Walter Gropius at Harvard. In 1983, he won the Pritker prize, regarded as the Nobel prize of architecture. After a rough start with the Hancock tower in Boston, in which a design flaw caused some windows to pop out, he had a long string of successes that included the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, and the glass pyramid at the Louvre and the Miho Museum in Kyoto, Japan. Pei had a long and prolific career. In addition to the well-known projects just mentioned he produced government offices, university buildings, apartments libraries and civic centers as well his his famed museums. The citation for the Pritzker Prize stated that “Pei’s architecture can be characterized by its faith in modernism, humanized by its subtlety, lyricism, and beauty."

I.M. Pei died at the age of 102 in 2019. In the obituary in the New York Times, Paul Goldberger wrote: “I. M. Pei, who began his long career designing buildings for a New York real estate developer and ended it as one of the most revered architects in the world, Best known for designing the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the glass pyramid at the entrance to the Louvre in Paris, Mr. Pei was one of the few architects who were equally attractive to real estate developers, corporate chieftains and art museum boards (the third group, of course, often made up of members of the first two). And all of his work — from his commercial skyscrapers to his art museums — represented a careful balance of the cutting edge and the conservative.[Source: Paul Goldberger, New York Times, May 16, 2019 nytimes.com ]

“Mr. Pei was a committed modernist throughout his life, and while none of his buildings could ever be called old-fashioned or traditional, his particular brand of modernism — clean, reserved, sharp-edged and unapologetic in its use of simple geometries and its aspirations to monumentality — sometimes seemed to be a throwback, at least when compared with the latest architectural trends. This hardly bothered him. What he valued most in architecture, he said, was that it “stand the test of time.”

“When Mr. Pei was invited to design the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, he had the opportunity to demonstrate his belief that modernism was capable of producing buildings with the gravitas, the sense of permanence and the popular appeal of the greatest traditional structures. When the building opened in 1978, Ada Louise Huxtable, the senior architecture critic of The New York Times, hailed it as the most important building of the era, and she called Mr. Pei, at least by implication, the pre-eminent architect of the time.

“Most other critics also praised Mr. Pei’s angular structure of glass and marble, constructed out of the same Tennessee marble as John Russell Pope’s original National Gallery Building of 1941, reshaped into a building of crisp, angular forms set around a triangular courtyard. Mr. Pei, many critics said, had found a way to get beyond both the casual, temporal air and the coldness of much modern architecture, and to create a building that was both boldly monumental and warmly inviting, even exhilarating. [Source: Paul Goldberger, New York Times, May 16, 2019]

I. M Pei’s Life

Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in Canton (now Guangzhou) on April 26, 1917, the son of Tsuyee Pei, one of China’s leading bankers.Paul Goldberger wrote in the New York Times: When he was an infant, his father moved the family to Hong Kong to assume the head position at the Hong Kong branch of the Bank of China, and when Ieoh Ming was 9, his father was put in charge of the larger branch in Shanghai. He remembered being fascinated by the construction of a 25-story hotel. “I couldn’t resist looking into the hole,” he recalled in 2007. “That’s when I knew I wanted to build.”

“He was brought up in a well-to-do household that was steeped in both Chinese tradition — he spent summers in a country village, where his father’s family had lived for more than 500 years, learning the rites of ancestor worship — and Western sophistication. Deciding to attend college in the United States, he enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania. But when he concluded that he was not up to the classical drawing techniques then being taught at Penn, he transferred to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from which he received a bachelor of architecture degree in 1940.

“At the recommendation of his father, who was concerned about the threat of war and the growing possibility of a Communist revolution in China, he postponed his plan to return home. Instead he enrolled at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, where he studied under the German modernist architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School.

“While he was at M.I.T., Mr. Pei met another Chinese national, Eileen Loo, who had come to the United States in 1938 to study art at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. Like Mr. Pei, she was from a distinguished Chinese family. The two married as soon as she graduated, in 1942. Eileen Pei began graduate work in landscape architecture at Harvard while her husband worked toward his advanced architecture degree, which he received in 1946.

“He taught briefly at Harvard and planned to return to China in time. But he was hired in 1948 by William Zeckendorf, who was looking for a talented young architect to head a new in-house design team. At a time when most of his Harvard classmates considered themselves fortunate to get to design a single-family house or two, Mr. Pei quickly found himself engaged in the design of high-rise buildings, and he used that experience as a springboard to establish his own firm,I. M. Pei & Associates, which he set up in 1955 with Henry Cobb and Eason Leonard, the team he had assembled at Webb & Knapp. In its early years, I. M. Pei & Associates mainly executed projects for Zeckendorf, including Kips Bay Plaza in New York, finished in 1963; Society Hill Towers in Philadelphia (1964); and Silver Towers in New York (1967). All were notable for their gridded concrete facades.

I. M Pei’s Buildings an Architecture Career

Paul Goldberger wrote in the New York Times: I. M. Pei & Associates became fully independent from Webb & Knapp in 1960, by which time Mr. Pei, a cultivated man whose quiet, understated manner and easy charm masked an intense, competitive ambition, was winning commissions for major projects that had nothing to do with Zeckendorf. Among these were the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., completed in 1967, and the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse and the Des Moines Art Center, both finished in 1968. They were the first in a series of museums he designed that would come to include the East Building (1978) and the Louvre pyramid (1989) as well as the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, for which he designed what amounted to a huge glass tent in 1995. It was perhaps his most surprising commission. “Mr. Pei, not a rock ’n’ roll fan, initially turned down that job. After he changed his mind, he prepared for the challenge of expressing the spirit of the music by traveling to rock concerts with Jann Wenner, the publisher of Rolling Stone. [Source: Paul Goldberger, New York Times, May 16, 2019]

“The Cleveland project would not be Mr. Pei’s last unlikely museum commission: His museum oeuvre would culminate in the call to design the Museum of Islamic Art, in Doha, Qatar, in 2008, a challenge Mr. Pei accepted with relish. A longtime collector of Western Abstract Expressionist art, he admitted to knowing little about Islamic art. As with the rock museum, Mr. Pei saw the Qatar commission as an opportunity to learn about a culture he did not claim to understand. He began his research by reading a biography of the Prophet Muhammad, and then commenced a tour of great Islamic architecture around the world.

“While the waffle-like concrete facades of the Zeckendorf buildings were an early signature of his, Mr. Pei soon moved beyond concrete to a more sculptural but equally modernist approach. Throughout his long career he combined a willingness to use bold, assertive forms with a pragmatism born in his years with Zeckendorf, and he alternated between designing commercial projects and making a name for himself in other architectural realms.

“Besides his many art museums, he designed concert halls, academic structures, hospitals, office towers and civic buildings like the Dallas City Hall, completed in 1977; the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, finished in 1979; and the Guggenheim Pavilion of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, finished in 1992. The Bank of China building, in Hong Kong, designed by Mr. Pei to look like an angular bamboo shoot, was completed in 1989. Mr. Pei was far from the obvious choice to design the Kennedy library and museum, but when Jacqueline Kennedy visited him in his office in 1964, she was so impressed by his erudition and elegant manners that she chose him on the spot.

“In 1979, the year after the National Gallery was completed, Mr. Pei received the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, its highest honor. At the same time that he was receiving plaudits in Washington, however, Mr. Pei was recovering from one of the most devastating setbacks any architect of his generation had faced anywhere: the nearly total failure of one of his most conspicuous projects, the 700-foot-tall John Hancock Tower at Copley Square in Boston.

“A thin, elegant slab of bluish glass designed by his partner Henry Cobb, it was nearing completion in 1973 when sheets of glass began popping out of its facade. They were quickly replaced with plywood, but before the source of the problem could be detected, nearly a third of the glass had fallen out, creating both a professional embarrassment and an enormous legal liability for Mr. Pei and his firm. The fault, experts believed, was not in the Pei design but in the glass itself: The Hancock Tower was one of the first high-rise buildings to use a new type of reflective, double-paned glass.

The 12 Most Significant Projects Of I.M. Pei

Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar, 2008

Suzhou Museum, Suzhou, China, 2006

Miho Museum, Kyoto, Japan, 1997

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland, USA, 1995

Bank of China Tower, Hong Kong, China, 1990

Le Grand Louvre, Paris, France, 1989

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, USA, 1979

National Gallery of Art East Building, Washington DC, USA, 1978

Dallas City Hall, Dallas, USA, 1978

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1973

Everson Museum, Syracuse, New York, United States, 1968

Luce Memorial Chapel, Taichung, Taiwan, 1963

[Source: United States Architecture News - May 17, 2019 worldarchitecture.org ]

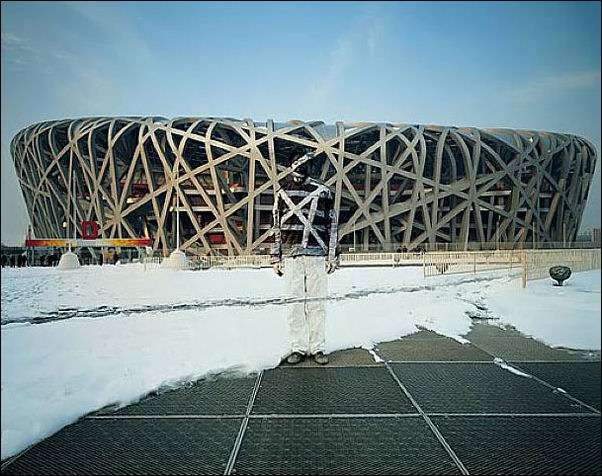

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and his take on the Bird's Nest Stadium

Wang Shu Wins 2012 Pritzker Prize

Chinese architect Wang Shu has won the 2012 Pritzker architecture prize, seen as the Nobel prize for architecture. Praised for his ‘strong sense of cultural continuity and reinvigorated tradition,” he is the first Chinese architect to win the prestigious award, which has been won by the likes of Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas. The decision to award him the prize acknowledges "the role that China will play in the development of architectural ideals", said Thomas Pritzker, chairman of the Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the $100,000 (£60,000) prize. The jury praised the importance of Wang's work in a country that is modernising and urbanising at top speed." As an architect, everyone dreams about the prize ... I'm very happy for him," said his wife Lu Wenyu. They run a joint practice, Amateur Architects , founded in 1997. In 2011 Wang was awarded the Gold Medal by France's Academy of Architecture.[Source: Mary Hennock, The Guardian, February 28, 2012]

"Unusually for an internationally decorated architect, Wang's five major projects are all in China, many in his home region of Zhejiang near Shanghai. They include three college campuses and the Ningbo History Museum, and his work typically mixes modern design with traditional material. China's rapid urbanisation makes the issue of "the proper relation of present to past — particularly timely", said jury chairman Lord Palumbo. Much of the new building in China is mediocre, with public buildings often emphasising giganticism and grandeur rather than style. The jury praised Wang's work as "exemplary in its strong sense of cultural continuity and reinvigorated tradition". Wang reworks Chinese styles with recycled materials; 2 million tiles from demolished traditional houses were used in the China Academy of Art's Xiangshan campus, in Hangzhou. A library at Suzhou University's Wenzhang Campus is a cluster of low cubes sunk half underground to reflect feng shui traditions, which oppose high buildings that block energy between mountains and water.

Wang Shu challenges China's obsession with scale China's massive building projects and instead pursues a a quest for 'reality' in architecture. Rowan Moore wrote in The Guardian: Wang “does not dispute the power and prevalence of huge new building projects in China, but that they are the only or inevitable architectural products his country has to offer. Amateur Architecture Studio , the practice he runs with his wife Lu Wenyu, is concerned with such things as memory, location, craft and identity, for "real feeling between people and construction" and the ways in which they can be recognised in the extraordinary time through which China is now passing. They do this with projects including a history museum in the coastal city of Ningbo and the rescue of a historic street, Zhongshan Road,in his home city of Hangzhou. [Source: Rowan Moore, The Guardian, December 15, 2012]

Born in 1963, Wang graduated from Nanjing Institute of Technology. His first job was to research building restoration and he worked with craftsmen for 10 years to gain a feeling for materials. He tries to recover what he has called the "handicraft aspect" of building design, in contrast to "professionalised, soulless architecture, as practised today". Wang is known for recycling destroyed Chinese buildings — especially tiles and wooden beams — in his own edgy structures. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books In the past, when China wanted showpiece buildings it turned to foreigners. Now architects like Wang are getting some commissions. It’s not clear, however, whether creative minds like Wang represent China’s future, or are an avant-garde enclave educated and feted in the West. [Source: Ian Johnson,New York Review of Books, June 6, 2013]

Architecture Boom in China

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “At a time when many Western economies are stagnant and many construction projects have been delayed or scaled back for lack of financing, China is on a major push to urbanize - building new office towers, apartment blocks, exhibition halls, stadiums, high-speed train stations and nearly 100 new airports. The boom is offering U.S. and European architects new opportunities and an economic lifeline, as much of their industry is struggling.”[Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, December 14, 2010]

“Many more projects are in the works - in some cases, the equivalent of entire cities, such as the sprawling industrial park being built in Shanghai's Pudong area. Every major city, it seems, is building or expanding a new central business district or financial center - often the size of the downtown of a midsize American city.”

"Train stations, airports - they really need everything," Martin Hagel, senior architect with the German firm GMP, based in Shanghai, told the Washington Post. "It's a place where architects want to be." He added, "The scale of things is unbelievable - building a new city is something you don't get to do often." The Chinese aren’t afraid of height either. Paul Katz of the New York firm Kohn Pedersen Fox, or KPF, said, "When people in the U.S. were not building tall buildings, we were here building tall buildings...There's hardly a building you see today that stood 15 years ago."

Another force behind the building and architecture boom in China is a lack of bureaucracy. Architects can design and build a project and put it to regular use in as little as a few years. In the United States, by contrast, with various bureaucratic hassles, projects can typically take more than a decade to come to fruition, and often much longer.

“The speed of development brings its own challenges, several architects said, Richburg wrote. “Among them, the foreign architects' desire to build environmentally sustainable buildings and cities often run smack into the local imperative to build it quickly - and often build it cheaply. For example, an American architect said that in the United States, buildings are typically designed to last 75 to 100 years, with many of the best-known and best-loved buildings, such as New York's Empire State Building, gracefully entering late middle age. But in China, he said, the private developers often want "a building to last 30 years" maximum. "Their idea of a building is like a commodity. It's disposable."

Foreign Architects in China

China is regarded as a place where foreign architects can be their most creative. They say working in China gives them an unparalleled chance to show off their expertise, experiment with cutting-edge designs, and use new energy-efficient "green" technologies. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, December 14, 2010]

CCTV HeadquartersIn China, "people have no preconceived notion of what building development should be," Silas Chiow, China director for the U.S. firm Skidmore Owings Merrill, or SOM, told the Washington Post. "That gives young architects an opportunity to try new ideas....China is almost like an experimental laboratory for different architects." SOM designed Shanghai's Jin Mao tower, one of the most visible buildings on the Pudong skyline, and Beijing's New Poly Plaza, with the world's largest cable-net-supported glass wall, and Tower III of the World Trade Center in Beijing. SOM also designed the futuristic car-shaped Pearl River Tower, with wind turbines and solar panels.

Not everyone is so pleased. "They're using China as their new weapons testing zone," Peng Peigen, a well-known architect and professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, told the Washington Post. "These kind of stupid things they build could never be built in their own countries, in this life, the last life or the next life." Peng praised "95 percent" of the many foreign architects in China. But he said the other 5 percent are ignoring the basic design rule that "form follows function." He criticized the Swiss-designed "Bird's Nest" stadium, used for the 2008 Olympics, as an "atrocious design" with a top-heavy roof, and called the French-designed National Grand Theater, known as "The Egg," a dysfunctional and "almost dangerous" eyesore.

“Foreign architects have been working in China since the late 1990s. But the real construction boom began in 2001. Many of the largest, most visible projects designed by foreign architects are government-funded. Some private developers - often prefer to see an international name on a structure that they hope will become a landmark. China has its own architects, but, as Peng noted, the communists who came to power in 1949 did not respect architecture as a profession. Since then, it has been officially recognized only since the 1980s, leaving too few experienced local architects.

New Architecture in Beijing

Beijing does not have a skyline like Shanghai, Hong Kong or New York. Its trophy buildings are scattered around the city in a rather haphazard way. This contrast with old Beijing, a mostly flat city in which courtyards and narrow lanes of the hutongs were part of grand geometric scheme with the Forbidden City at the center of the city’s central north-south axis.

Old Beijing — designed for pedestrians, camels and Imperial processions — has proven to be a bad frameworks for a modern city. There are not that many conventional streets and blocks. The hutongs are like masses that have to be obliterated to be updated. As the 2008 Olympics approached a number of foreign architects were asked to come in and build new building, some of them quite radical. The result:

Some of the world’s most spectacular modern structures. Some — like the Bird’s Nest stadium and the Water Cube made for the Olympics, Norman Foster’s new airport terminal and Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV headquarters — have received rave reviews from architecture critics. While others — namely the Egg concert hall — have been panned. Some Beijing residents are not so pleased with new structure, calling the non-Chinese architects “foreign devils,” and complaining their work disrupts Beijing’s feng shui. There were even nationalist-tinted accusations that the building — mostly designed by Europeans — were unsafe.

Bird’s Nest Stadium

Bird’s Nest Stadium (Olympics Area) is the nickname of the National Stadium, which hosted the opening and closing ceremonies, the track and field events and important soccer games at the 2008 Olympics. One of the world's most famous new structures, is was designed by the Pritzer-Prize-winning Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Piere de Meuron, who became famous when they converted London’s dour Bankside Power Station into London’s Tate Modern museum.

The Bird’s Nest name was given by the Chinese public to the stadium as it being built because it resembled a nest. The name was considered a compliment because bird’s nest soup is a highly-valued delicacy associated with special occasions. The architects originally likened the design to the finely cracked glazing on Chinese pottery.

Described by the Times of London as “the world’s most iconic building in this decade of iconic buildings,” the National Stadium won the inaugural Design of the Year for Architecture Award from the Design Museum. Ai Weiwei, an artist and consultant for the project, said, “We didn’t design it to be Chinese. It’s an object for the world.”

Herzog and de Meuron’s design beat out 13 other finalists. De Meuron told the Times of London, “We wanted to do something hierarchal, to make not a big gesture you’d expect in a political system like that but something for 100,000 people on a human side without being oppressive. Its about disorder and order. It seems random, chaotic, but there’s a very clear structural rationale.” Herzog said, “The Chinese like to hang out in public spaces. The main idea was to offer them a playground." During the Olympics small models of the Bird’s Nest stadium were hot sellers. Design of the Bird’s Nest Stadium The Beijing Olympic Stadium is 330 meters long, 220 meters wide and 69.2 meters tall and covers 250,000 square meters and has 91,000 seats and a capacity of 100,000 people. It is a complex, slightly off-kilter, elliptical 42,000 ton lattice work of steel surrounding a concrete stadium bowl.

See Separate Article MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com

National Center for Performing Arts

National Center for Performing Arts (opposite the Forbidden City) is an opera house with a controversial design by the French architect Paul Andreu that its supporters hope will leave a Sydney-Opera-House like stamp on Beijing. Situated somewhat incongruously among massive Stalinist buildings at Tiananmen Square and larger than New York’s Lincoln Center, it features a massive bubble-like titanium shell, 149,500 square meters of floor space and three halls: a 2,416-seat opera house, a 2,017-seat concert hall, and a 1,040-seat theater, plus a small experimental theater.

The design for National Center has been compared to a flying saucer, a hatching dinosaur egg and a giant blob. For many Chinese it looks like an egg set in a pot of boiling water, and the name “The Egg” has stuck. Its total cost: $365 million, which works out to about $90,000 a seat. Critics, complain the new structure is too costly and ugly and has been built with no considerations to its surroundings or China’s history. One blogger wrote: “It looks like a quasi-foreign devil in the historical palace area. If you weren’t told it was the national theater you would probably think it was an oil tank or a huge warehouse.” Some say the modernist design disrupts the feng shui of Beijing and therefore threatens the entire nation. Many dismiss it a “ben” dan (‘stupid egg’) or “huai dan” (‘rotten egg’).

The 56-meter-high elliptical shell, which Andreu said is “a symbol of rebirth,” is designed to look as if it is floating on water. It sits in the middle of a lake, with 16,000 cubic meters of water, enough to fill 42 Olympic-size swimming pools. At night the titanium and glass structure glows and is reflecting in the water, some say, like a pearl or a rising sun. The dome in the pool is intended to represent the Chinese concept of a round sky and square earth.

There are no doors. People enter through a glass-roofed venue and staircase situated below the reflecting pool. Some critics have said that the entrance comes off as ‘silly and cumbersome” rather than dramatic and make the building difficult to evacuate in an emergency (one has to cover a distance of 250 meter to reach freedom).

See Separate Article MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com

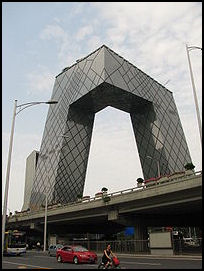

CCTV Headquarters

CCTV Headquarters is one the world’s boldest and most spectacular buildings in the world. Created by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and his partner Ole Schreeren of the radical Dutch firm OMA, it is comprised of three interlocking “Ls that form a kind of twisted cube and bring to mind an Escher painting. Some have called the building a modern-day Colossus of Rhodes. Others have and compared it with the legs of a robot or “a pair of trousers.” Many Beijingers call it the Big Shorts and make jokes about what it would be like to work in the building’s crotch. For a skyscraper the CCTV headquarters is rather short, only fifty-one floors (768 feet high), and squat but it has more office space (6.5 million square feet, or 750 square meters) than any other building in China and is the second largest office building in the world after the Pentagon. For all that has been written about it comes off as monumental, austere and intellectual rather than showy and gimmicky. The soft gray color of the glass is not all that different from the soft gray skies that dominate most Beijing days. The diagonal grid of the steel framework is visible with the densest concentration of steel around te cantilever where the structural stresses are greatest.

The CCTV building looks very different from different angles and distances. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New Yorker, “A vast structure of steel and glass, it is a dazzling reinvention of the of the skyscraper, using size not to dominate but to embrace the viewer...Looking from a distance like a gigantic arch, it is a continuous loop, a kind of square doughnut. Two vertical sections, which contain offices lean precariously inward, connected by two horizontal sections containing production facilities, one running along the ground. The other a kind of bridge in the sky. When you get closer, you see that each horizontal section is made up of two pieces that converge in a right angle. The top section, thirteen stories deep, is dramatically cantilevered out over open space, five hundred and thirty feet in the air, and it seems ot reach over you like benign robot. The novelty of the form...takes time to comprehend; the building seem to change as you pass it.”

The CCTV building can be appreciated without craning you neck to see the top. When viewed from across the street it looks like three distinct buildings: the base, south tower and north tower.Koolhaus told Vanity Fair, “It has a delicacy despite its size. Its something that’s not really a tower, but is three-dimensional, so it defines urban space.” About 10,000 people will work inside. One feature of the building is that these people will be able to look out the window and see the building they work in.

See Separate Article MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com

Pudong New Area of Shanghai

Pudong New Area (east side of Huang Pu River on the side opposite the Bund) is a 208-square-mile (522-square-kilometer) area with industrial parks, some of the world’s tallest skyscrapers, billion dollar auto and steel plants, foreign factories, and housing developments. There are separate zones for finance (Luijazui), high tech development (Zhangjiang), export processing (Jinqiao) and trade (Waigaoqiao). Dong means east side of the river. The heart of Pudong is basically a group of trophy skyscrapers plunked down in what used to be rice fields. Conceived by former Shanghai mayor and Chinese prime minister Zhu Rongji and designed to be China's premier "free economic zone," Pudong was built from scratch with its own international airport. Many of the showcase building are designed by famous architects from Italy, Japan, Spain and the United States. The land used to be occupied by marshes, farms, once-story building and rice paddies.

Central Pudong is filled with new skyscrapers, office buildings and hotels and offices for over 2,000 foreign companies, including many in the Fortune 500. Among the factories there is $1.5 billion General Motors plant that churns out Buicks. On the far eastern end, about 32 kilometers from downtown Shanghai, is the new international airport connected to downtown Shanghai by the maglev train. There is an impressive river walk with shops and cafes and good views of river traffic and sights on the opposite shore. The area as a whole isn’t very walker-friendly. The wide roads are difficult to cross.

The Oriental Pearl TV and Radio Tower (in Pudong) is a massive 1,500-foot-high, multicolored, rocket-ship-shaped structure located across the Huangpu River from the Bund. The centerpiece of the Pudong development area and the tallest television tower in Asia, it contains two immense disco-ball-like geodesic domes with elevated shopping malls inside. The tower is the a futuristic symbol of Shanghai. Purple and pink, it cost $100 million and rises above rows of new concrete apartments and glass skyscrapers. The tower is open daily from 8:15am to 9:15pm. The entrance fee varies from $6 to $12, depending on how high you want to go. There are often long lines to board the elevator to the observation area, where there is an outstanding view.

Shanghai Tower(Metro Line 2, Lujiazui Station, in Pudong) is the second tallest building in the world and the tallest building in China (as of 2020). It is 632 meters (2,073 feet) tall and has 128 floors, 106 elevators and indoor sky gardens. Completed in 2015, it is the tallest twisted building and is considered an architectural marvel but, according to the South China Morning Post, as of 2017 it still had many unoccupied floors due to unsolved technical problems related to fire prevention.

Jin Mao Tower (near the Oriental Pearl TV and Radio Tower in Pudong) was the world’s 6th tallest building as of early 2008. Resembling across between a pagoda and a Manhattan skyscraper, it cost $540 million and has 88 floors and is home to the world’s highest hotel (the Hyatt) and the world's highest health club (at the Hyatt) and the world’s longest laundry shoot, which run’s from 87th floor of the Hyatt hotel to the its basement. It used to be home to the world’s highest hotel (the Hyatt) and the world's highest health club (at the Hyatt) until it was surpassed by the Hyatt next door in the Shanghai World Financial Center.

See Separate Article PUDONG AND SKYSCRAPERS AND FAST ELEVATORS IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com

Shenzhen: the Design Capital of China?

“Shenzhen is “the birthplace of China’s modernisation over the last 40 years”, Ole Bouman, director of the Design Society, said. In 2008, the city was named a UNESCO Creative City of Design and each year hosts high-profile design events, including December’s Shenzhen Biennale for Architecture and Urbanism. Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has called Shenzhen a “generic city”: malleable enough to change its form with the times.[Source: Cathy Adams SCMP, December 1, 2017]

Cathy Adams wrote in the SCMP, Shenzhen’s “creative zones include the OCT Loft across town, a palm-studded district of former industrial buildings turned contemporary art park. Visitors sip tiny coffees at arty cafes (Whatever Cafe), buy design trinkets in fancy boutiques (IM Loft Shop) and wander around high-ceilinged galleries such as the OCAT Contemporary Art Terminal. Nearby is the spaceship-like OCT Creative Exhibition Center, showing landmark exhibitions.

“Further into the heart of Shenzhen’s dense financial district is the just-completed neofuturistic, cloud-like Museum of Contemporary Art and Planning Exhibition, designed by Austrian architect firm Coop Himmelblau. Shenzhen is now so design-friendly it’s been chosen as the inaugural destination for a three-in-one Muji store, hotel and restaurant – a spin-off of the Japanese homeware brand – slated to open by the end of this year.

““By raising expectations among the public on what design can do for them, we intend to leverage the role of the design communities and provide a position towards a more creative China,” says Bouman. “Design in such a city has a different role compared with design in Milan, London, or even Shanghai. Design in Shenzhen breathes an almost existential drive.”

His and Hers House by Wutopia Lab is a good example cutting edge Chinese architecture. It was named by Dwell as one of 12 incredible projects by Chinese firms that are raising the bar for adaptive reuse and new builds alike. Michele Koh Morollo of Dwell wrote: “As part of the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture, Shanghai–based architecture practice Wutopia Lab renovated two buildings in Dameisha Village, an urban slum with traditional Chinese characteristics, and turned them into a light blue and pink house that explores themes of traditional masculinity, femininity, and assigned gender roles. [Source: Michele Koh Morollo, Dwell, February 5, 2019]

See Separate Article SHENZHEN: SKYSCRAPERS, MINIATURE CITIES AND CHINA’S FASTEST-GROWING AND WEALTHIEST CITY factsanddetails.com

New Century Global Center: World's Largest Building

New Century Global Center(Tianfu New Area, Metro Line 1) is a multipurpose building that holds the distinction of being the world's largest building in terms of floor area. The 100-meter (330 feet)-tall structure is 500 by 400 meters (1,600 by 1,300 feet) in size with 1,700,000 square meters (18,000,000 square feet) of floor space. The Boeing Everett Factory in Everett, Washington, in the United States is the largest building in terms of volume, while AvtoVAZ main assembly building has the largest footprint. New Century Global Center will eventually face the Chengdu Contemporary Arts Center, designed by famed Bagdad-born architect Zaha Hadid, who died in 2016.

New Century Global Center houses offices, conference rooms, a university complex, two commercial centers, an IMAX cinema and a pirate ship and an Olympic-size skating rink. The centerpiece of the building is the "Paradise Island Water Park" with a ), with a 5,000 square meter (54,000 square foot) artificial beach, backed by a giant 150 by 40 meter (490 by 130 foot) screen forms a horizon offering sunrises and sunsets. At night, a stage extends out over the pool for concerts. A platform overlooking the pool has a food court and entrance underneath at the floor level. The Intercontinental Hotel has 1,009 rooms spread over 6x8 story blocks around the edge of the complex.

After it opened, Associated Press reported: “Move aside Dubai. China now has what is billed as the world's largest building — a vast, wavy rectangular box of glass and steel...The mammoth New Century Global Center has 1.7 million square meters (19 million square feet) of floor space — or about 329 football fields — edging out the previous record-holder, the Dubai airport. [Source: Associated Press, July 12, 2013]

See Separate Article New Century Global Center: World's Largest Building factsanddetails.com

Xi Jinping: ‘No More Weird Architecture’

Some Beijing residents are not so pleased with new structure, calling the non-Chinese architects “foreign devils,” and complaining their work disrupts Beijing’s feng shui. There were even nationalist-tinted accusations that the building — mostly designed by Europeans — were unsafe.

Some find the debate about high profile buildings amusing because there is so much bad architecture around. Many nondescript buildings have kitchy pagoda designs or some other eastern ornament to meet demands by the city’s mayor for buildings to look Chinese. New development are dominated by blocky apartments and offices that have nothing to distinguish them except their ugliness. Among the worst buildings are those that attempt to copy masterpieces of Western architecture. One architect told the New York Times, “They’re like copies of copies. Kitsch derived from kitsch.”

In 2014 Chinese president Xi Jinping said he had enough of China’s fascination with what he called “weird architecture,” the state-run Xinhua news agency reported. Megan Willett wrote in Business Insider: “Speaking at a literary symposium in Beijing last week, Xi’s two-hour speech took shot at Chinese architects and artists who have designed avant-garde style buildings. Instead, he said that art should “be like sunshine from the blue sky and the breeze in spring that will inspire minds, warm hearts, cultivate taste, and clean up undesirable work styles.” In other words, the speech was a call for more traditional Chinese art that is patriotic, socialist, and nationalistic at its core. [Source: Megan Willett, Business Insider, October 21, 2014]

“Xi believes that the art and architecture in China should appeal to the average Chinese citizen, who should also be the main subject of all artwork. His sentiment hearkens back to late Chinese leader Mao Zedong’s idea that the working class in China should not only be the major audience for all art, but that it should be a reflection of their everyday lives, according to Xinhua.

“Xi’s speech comes at a time when China is being noticed and appreciated for its architecture. In 2012, Wang Shu, an Hangzhou architect, became the first man who was born and working in China to win the Pritzker Prize, the architect’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize, according to the Wall Street Journal.

“Of course, not all of China’s bizarre buildings are a hit. Rem Koolhaas’ CCTV headquarter building was nicknamed “big pants” for its bizarre shape,a building in the Jiangsu province was mocked for looking like a clay teapot in the Jiangsu province, and there was also a bizarre 33-story building in Guanzhou that looked like a giant coin.

“Xi also touched on the fact that China is known for copying buildings from the rest of the world, saying that problems like plagiarism and unoriginality were not helping the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation. In the past, Chinese architects have copied famous architect Zaha Hadid as well as created replicas of famous world monuments. They even built a miniature version of Italy. The speech addressed the rampant corruption in Chinese architecture that Xi is trying to curb as well. The Chinese president said that artists should not be “slaves” to the market and the work itself should not have “the stench of money.”

Image Sources: Wiki commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021