TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA

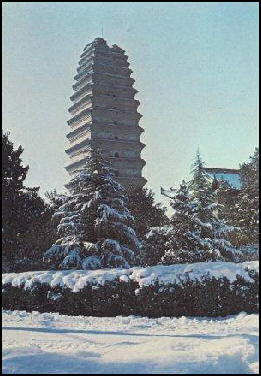

Songyue Pagoda

Traditional Chinese buildings and structures include pavilions, high-arched stone bridges, and multi-storied pagodas. Some Chinese architecture seem intent on overpowering nature with symmetry and concentric rectangles. Traditional houses are rectangular and have courtyards enclosed by high walls. Roofs are sloped, curving upward at the edges.

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”“In the realm of structural engineering and technical Chinese architecture, there were also government standard building codes, outlined in the early Tang book of the Yingshan Ling (National Building Law). Fragments of this book have survived in the Tang Lu (The Tang Code), while the Song dynasty architectural manual of the Yingzao Fashi (State Building Standards) by Li Jie (1065-1101) in 1103 is the oldest existing technical treatise on Chinese architecture that has survived in full. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (712 — 756) there were 34,850 registered craftsmen serving the state, managed by the Agency of Palace Buildings (Jingzuo Jian). [Source:Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Matt Turner wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: “In his recent book A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture, David Wang sees much of the confusion about “Chinese style” architecture having originated in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, when China sought to modernize — largely in response to invasions by hostile and technologically advanced foreign powers. During that time intellectuals, including architects, framed architectural modernization in terms of ti,Chinese essence, and yong, technical application. This allowed for the architectural fantasy of improving buildings’ structures while at the same time keeping their Chineseness intact, usually through stereotypical features. This is still a popular way of thinking about architecture in much of China, and is in part the reason for the destruction of old neighborhoods and their subsequent reconstruction: old neighborhoods often lack sufficient sanitation facilities, so they can be razed and rebuild as modern structures retaining traditional-looking façades. In contrast to Western architectural practice, which Wang argues modernized with much less effort, Chinese architecture developed a near-obsession with technical features of Western modernism that had little to do with the legacy of Chinese architecture. The result was a confusion of essence and application. [Source: Matt Turner, Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel, April 16, 2018]

“According to Wang, traditional architectural practice in China was not overly focused on the appearance of buildings, but instead on their social application. Traditional building methods “formalized Chinese imperial construction as an expression of social hierarchy,” meaning that, taking the Forbidden City as a model, homes and commercial districts would have been built in the same manner, though on a smaller scale. Their layout would mirror the hierarchy of the palace: as one moved from chamber to chamber to garden, from inside to outside, the individual would walk through social rank, “conforming to the Confucian social order.”

See Separate Articles: ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com/china ; TEMPLE OF HEAVEN Factsanddetails.com/China HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL HOUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOUSES IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CAVE HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com. Edited by professors and graduate students from Columbia, Yale, and the University of Virginia, this site offers thousands of photographic images of Asia's diverse architectural heritage at hundreds of sites in 17 countries. Chinese Architecture china-window.com ; Chinese Architecturechinaetravel.com ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; House Architecture Yin Yu Tang pem.org ; House Architecture washington.edu ; House Interiors washington.edu: Mao-Era Architecture See Wikipedia article on Mao Mausoleum Wikipedia ; Oriental Architecture ; Forbidden City: Book: “Forbidden City” by Frances Wood, a British Sinologist. Wikipedia Article Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites UNESCO Temple of Heaven: Wikipedia article Wikipedia UNESCO World Heritage Site UNESCO

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Architecture: A History” by Nancy Steinhardt Amazon.com “Chinese Architecture” by Qijun Wang Amazon.com; “Chinese Architecture” by Fu Xinian, Guo Daiheng, et al. Amazon.com; “Houses of China” by Bonnie Shemie (1996) Amazon.com; “A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by David Wang Amazon.com “Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation” by Ronald G. Knapp , A. Chester Ong , et al. Amazon.com; “Ritual and Ceremonial Buildings: Altars and Temples of Deities, Sages, and Ancestors” Amazon.com; “Taoist Buildings: The Architecture of “The Grand Documentation: Ernst Boerschmann and Chinese Religious Architecture” (1906–1931) by Eduard Kögel Amazon.com

Traditional Chinese Architecture Recognized by UNESCO

Chinese traditional architectural craftsmanship for timber-framed structures was inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: Standing as distinctive symbols of Chinese architectural culture, timber-framed structures are found throughout the country. The wooden components such as the columns, beams, purlins, lintel and bracket sets are connected by tenon joints in a flexible, earthquake-resistant way. The surprisingly strong frames can be installed quickly at the building site by assembling components manufactured in advanced. In addition to this structural carpentry, the architectural craft also encompasses decorative woodworking, tile roofing, stonework, decorative painting and other arts passed down from masters to apprentices through verbal and practical instruction. [Source: UNESCO]

“Each phase of the construction procedure demonstrates its unique and systematic methods and skills. Employed today mainly in the construction of structures in the traditional style and in restoring ancient timber-framed buildings, Chinese traditional architectural craftsmanship for timber-framed structures embodies a heritage of wisdom and craftsmanship and reflects an inherited understanding of nature and interpersonal relationships in traditional Chinese society. For the carpenters and artisans who preserve this architectural style, and for the people who have lived in and among the spaces defined by it for generations, it has become a central visual component of Chinese identity and an important representative of Asian architecture. [Source: UNESCO]

Traditional design and practices for building Chinese wooden arch bridges was also inscribed in 2009 on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage and designated in Need of Urgent Safeguarding Wooden arch bridges are found in Fujian Province and Zhejiang Province, along China’s south-east coast. The traditional design and practices for building these bridges combine the use of wood, traditional architectural tools, craftsmanship, the core technologies of ‘beam-weaving’ and mortise and tenon joints, and an experienced woodworker’s understanding of different environments and the necessary structural mechanics. The carpentry is directed by a woodworking master and implemented by other woodworkers. The craftsmanship is passed on orally and through personal demonstration, or from one generation to another by masters teaching apprentices or relatives within a clan in accordance with strict procedures. These clans play an irreplaceable role in building, maintaining and protecting the bridges. As carriers of traditional craftsmanship the arch bridges function as both communication tools and venues. They are important gathering places for local residents to exchange information, entertain, worship and deepen relationships and cultural identity. The cultural space created by traditional Chinese arch bridges has provided an environment for encouraging communication, understanding and respect among human beings. The tradition has declined however in recent years due to rapid urbanization, scarcity of timber and lack of available construction space, all of which combine to threaten its transmission and survival.

Paintings of Traditional Chinese Architecture

“Peace for the New Year” by Ting Kuan-p'eng

“Four Events of the Ching-te Reign”, by an anonymous Song Dynasty (960-1279) artist, is an ink and color on silk handscroll, measuring 33.1 x 60 centimeters, According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “T'ai-Qing Hall is composed of a raised foundation, a column, bracket, and eave system, and a projecting veranda around the building all arranged in an orderly and symmetrical manner. The wall facing the viewer is composed of seven bays. The center bay is slightly wider than the secondary and tertiary bays to either side. The hip-and-gable roof with double eaves has, at the top, ch'ih-wen ornaments at either end of the main ridge. Animal heads serve as hip ornaments. The timber used for the bracket sets appears quite large, transferring the weight of the roof to the columns under the eaves. Simple yet powerful, they create a straightforward style reminiscent of that from the Tang dynasty (618-907). This work reveals a hierarchical "dual entry" system used in the Tang and Song Dynasties, in which the left stairs were reserved for the "host" and the right for "guests. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Retiring from Court” by Li Sung (fl. ca. 1190-1264), Song Dynasty, is an ink on paper album leaf, measuring 24.5 x 25.2 centimeters: “Following the central axis of the building takes the viewer from the entrance to the interior along a symmetrical arrangement. This building complex, surrounded by covered walkways, is built directly atop an elevated slab-faced foundation, which has a curb and pier at each end. The entrance hall rests on a tall platform with sloping (entasis) walls and has bracketing and an elevated terrace. A series of steps lead up to the central bay with a railing on either side and the triangular "elephant-eye" pattern below, which correlates to the Sung technique illustrated in Ying-tsao fa-shih (Building Standards). The tall central structure behind has a double-eave roof with a cross-shaped ridge and flying rafters. The ch'ih-wen ornaments at the ends of the main ridge have wide-open mouths and tall curving tails, which are typical of the style from the Sung, Chin, and Liao periods. A animal cap lies below the corner ornaments.

“Cooling Off by a Waterside Hall “ by "Master" Li, Song Dynasty (960-1279), is an ink and color on silk album leaf, measuring 24.5 x 25.4 centimeters. “The cross-shaped ridge of the double-eave, hip-and-gable roof shown here has curved ends, ridge ornaments, sloping tiles, rafters and eaves, and sets of animal cap ornaments all rendered with exceptional detail. The barge-board panel is highly decorated. Below the roof is a bracketing system in which two intermediary brackets are found above the central bay and a single bracket above the secondary bays on either side. This form of construction closely correlates to Song Dynasty building practices.

“The bracket sets are located above the lintel and protrude from the corner column. There is no "topping lintel (p'u-po fang)," which was almost always found after the Chin (1115-1234) and Southern Song (1127-1279). The building here is situated on an elevated foundation, followed by a post-and-lintel structure, and then bracketing to support the floor above. The veranda around the structure is decorated with railings. The covered bridge extending from the building has a support, visible to the right, along with two center rows of columns known as p'ai-ch'a chu. Consequently, this work is important for not only studying water control, but also Sung wooden bridge construction. Such apparent understanding of architecture suggests that this work came from the hand of a major Southern Song court artist, such as Li Sung, who himself is said to have started his career as a carpenter. This is the fourth leaf from the album "Ming-hui chi-chen."

“Pavilion Facing the Sea”, by an anonymous, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) artist, is an ink and color on silk hanging scroll, measuring 159.8 x 93.2 centimeters. The main building here presides magnificently on top of a city wall. With a triple-eave, hip-and-gable, cross-shaped roof, the gables are shown with crescent beams and decoration (such as vertical ch'ui-yu). To the immediate left of the building is an attached pavilion. The columns inside are large, which allow for an expansive interior. An elevated terrace extends around the sides with railings, and the brackets under the eaves and yen-ch'ih-pan panels are below. The decoration to the main and subsidiary ridges, as well as the eave rafters, is finely rendered. The areas where the outer eave lintels and columns meet have also been painted.

“Dragon Boat Regatta” by Wang Chen-p'eng

“The city wall itself is composed of slabs with turrets running along the outer edge. A gate is shown below the pavilion in the foreground with supporting columns (p'ai-ch'a chu) inside. Between the gate tower and the main building along the wall is a stairway, at the base of which is a wu-t'ou gate (which has uprights but no crossbeam or roof), also serving as an entrance to the building complex inside. White lines accent the lines of the ridges, making them stand out clearly.

“Peace for the New Year” by Ting Kuan-p'eng (fl. ca. 1708-1771), Qing Dynasty, is an ink and color on silk hanging scroll, measuring 179.3 x 108.4 centimeters. “This work is one painting of the imperial activities in the twelve lunar months. Here is a representation of the seventh day of the first month, when colored lanterns are hung everywhere. This painting, in fact, represents a faithful view of part of the Forbidden City, including the city wall and streets beyond. The main building in the lower left, for example, can be identified as the Yen-ch'un Pavilion with its four-cornered, pointed roof topped by a round glazed piece. Behind is the Ching-sheng Studio, while to the right is the Chi-yun Building. In the lower right is the Hui-feng Pavilion and in the lower left the Chi-ts'ui Pavilion. The series of curving rolltop roof buildings to the lower right represent the Ching-i Hall. In fact, varieties of roof types are found here, including conical pointed and pyramidal, gabled, curved, and connected ones. The variety of tiles also indicates differences in rank. Windows and doors are in the official style, and the lintels are delicately painted with patterning.

“Dragon Boat Regatta” by Wang Chen-p'eng (1275-1328), Yuan Dynasty, is an ink on silk handscroll, measuring 32.9 x 178 centimeters, “This is an interpretation of a regatta that was once held at the Chin-ming Pond in front of the Pao-chin Hall (shown at the far left with a cross-shaped roof), where the banquet was held and in front of which is seen a pennant in the water indicating the end of the race. The large terrace in front of the hall extends over the water and is supported by numerous columns underneath. The hall itself is surrounded by an open area. This handscroll reveals a large variety of brackets painted with great detail, and the cantilever tips in the bracketing point up as well as down. In Yuan dynasty paintings of buildings, the number and height of brackets were increased, creating for an exceptionally intricate and complex scene.

“A lintel and topping lintel (p'u-po fang) are shown above the columns as they decoratively protrude from the corners. The first main building from the right features "column elimination," which involves cutting off the lower parts of select columns. Here, they are supported above with crescent beams and bear lotus designs. Combined with the large timber of the columns, unhindered space can thus be created.

Forbidden City

The Forbidden City (near Tiananmen Square) was the home of 24 Ming and Qing emperors, their families, and their coterie of eunuchs and servants for 600 years from 1406, when construction began, until 1911, when the Qing dynasty was ousted and the Imperial era ended. Ordinary people were not allowed inside its gates---which is why it was called the Forbidden City---until 1925 when members of the public entered it for the first time.

Officially known as the Palace Museum and also called the Imperial Palace, it is surrounded by a 16-meter (52-foot) -wide, two-meter-deep moat. Its chambers and storehouses contain 1,052,653 rare and valuable objects that aren’t even displayed. The walls that surround the court are 2,428 meters long. In the Imperial era there was residential quarter outside the walls where courtiers and government officials lived. The Forbidden City was the place where the emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties lived and ran their Imperial bureaucracy. It is the largest and best-preserved mass group of palaces in China. The palaces are surrounded on four sides by red, 10-meter-high walls which extend 760 meters (0.47 miles) from east to west and 960 meters (0.6 miles) from north to south. Built by tens of thousands of people, the palace took over 14 years and 32 million bricks to complete. Twenty-four Ming and Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) emperors worked and lived but few of the original buildings remain. The last emperor Puyi, known in the West for the film "The Last Emperor," moved out of the complex in 1925.

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The palace had been off-limits to the public until the abdication of the last emperor, Puyi, in 1911. The walled city has 980 buildings in a geometric layout, many with poetic names like the Hall of Supreme Harmony and the Studio of Exhaustion from the Diligent Reign. Almost everything is painted a dusty hue of vermilion, and there is an air of faded grandeur about the place, with tall grass growing through cracks in the vast stone courtyards and yellow tile roofs. Still, the Palace Museum is the most popular tourist attraction in China, with 8 million visitors a year, most of them Chinese. The modern capital of Beijing is laid out around its walls. In many ways, the Forbidden City is the psychic heart of the nation; it is at the intersection of imaginary north-south and east-west axes that ancient geomancers thought marked the center of China, hence the world, with the optimal feng shui. It is no coincidence that the Communist Party chose to rule from the adjacent Zhongnanhai compound that hugs its western walls — today the true forbidden city.” [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 27, 2011]

See Separate Articles: FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com ; PLACES AND BUILDINGS WITHIN THE FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com

Temple of Heaven

Temple of Heaven (within the Temple of Heaven Park four kilometers south of Tiananmen Square) is a complex of Taoist buildings situated in southeastern Beijing. Literally the Altar of Heaven, it was visited annually by the Emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911), who prayed to Heaven for good harvests.

The Temple of Heaven complex covers an area of 270 hectares, about three times the size of the Forbidden City. The main buildings in the park were built in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) by Emperor Yongle for worshipping the heaven and the earth. The complex was extended during the reign of Emperor Jiajing in the 16th century and was renovated in the 18th century by Emperor Qianlong. The temple has been described as "the noblest example of religious architecture in the whole of China." The buildings found here were built at the same time as the Imperial Palace, and they are noted for their exquisite architecture and harmonious placement within the park among rows of cypress trees, some of which are said to be 800 years old.

The Temple of Heaven was designed to mark the meeting point between heaven and earth. Known to Chinese as Tiantan, it was expanded and reconstructed during the reigns of the Emperor Jiajing and Emperor Qianlong. Built to offer sacrifice to Heaven, the Temple of Heaven is enclosed with a long wall. The northern part within the wall is semicircular, symbolizing the heavens and the southern part is square symbolizing the earth. The northern part is higher than the southern part. This design shows that the heaven is high and the earth is low and the design reflected an ancient Chinese thought of ‘The heaven is round and the earth is square’. It is regarded as a Taoist temple, although Chinese Heaven worship, especially by the reigning monarch of the day, actually predates Taoism.

See Separate Article TEMPLE OF HEAVEN factsanddetails.com

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests

Ancient City of Ping Yao

According to UNESCO: The Ancient City of Ping Yao is a well-preserved ancient county-level city in China. Located in Ping Yao County, central Shanxi Province, the property includes three parts: the entire area within the walls of Ping Yao, Shuanglin Temple 6 kilometers southwest of the county seat, and Zhenguo Temple 12 kilometers northeast of the county seat. The Ancient City of Ping Yao well retains the historic form of the county-level cities of the Han people in Central China from the 14th to 20th century.

Founded in the 14th century and covering an area of 225 hectares, the Ancient City of Ping Yao is a complete building complex including ancient walls, streets and lanes, shops, dwellings and temples. Its layout reflects perfectly the developments in architectural style and urban planning of the Han cities over more than five centuries. Particularly, from the 19th century to the early 20th century, the Ancient City of Ping Yao was a financial center for the whole of China. The nearly 4,000 existing shops and traditional dwellings in the town which are grand in form and exquisite in ornament bear witness to Ping Yao’s economic prosperity over a century. With more than 2,000 existing painted sculptures made in the Ming and Qing dynasties, Shuanglin Temple has been reputed as an “oriental art gallery of painted sculptures”. Wanfo Shrine, the main shrine of Zhenguo Temple, dating back to the Five Dynasties, is one of China’s earliest and most precious timber structure buildings in existence.

The Ancient City of Ping Yao is an outstanding example of Han cities in the Ming and Qing dynasties (from the 14th to 20th century). It retains all the Han city features, provides a complete picture of the cultural, social, economic and religious development in Chinese history, and it is of great value for studying the social form, economic structure, military defense, religious belief, traditional thinking, traditional ethics and dwelling form.

The site is special because: 1) “The townscape of Ancient City of Ping Yao excellently reflects the evolution of architectural styles and town planning in Imperial China over five centuries with contributions from different ethnicities and other parts of China. 2) The Ancient City of Ping Yao was a financial center in China from the 19th century to the early 20th century. The business shops and traditional dwellings in the city are historical witnesses to the economic prosperity of the Ancient City of Ping Yao in this period.

See Separate Article TAIYUAN AND PINGYAO AREA OF SHANXI factsanddetails.com

Siheyuan (Courtyard Houses) in Dingcun Village

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: Among the 40 private residential houses existing now, many of them are Siheyuan. Private houses of Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) arranged the gate at the southeast corner. These buildings are usually lower with over hanging gable roof and gentle tiles. The materials are bulky and the eaves and lintels are drawn with colours. The woodcarvings are fewer but simple and unsophisticated. The distribution of the whole buildings is in order and the courtyards are not only spacious and comfortable but artistic and pleasing to the eye. Buildings built in the early or mid periods of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.) adopted the shape of ‘ ', the middle hall separates the front and back yards and the gate is designed on the axis. The yard is long and narrow and the small yard is deeper. [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: Among the 40 private residential houses existing now, many of them are Siheyuan. Private houses of Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) arranged the gate at the southeast corner. These buildings are usually lower with over hanging gable roof and gentle tiles. The materials are bulky and the eaves and lintels are drawn with colours. The woodcarvings are fewer but simple and unsophisticated. The distribution of the whole buildings is in order and the courtyards are not only spacious and comfortable but artistic and pleasing to the eye. Buildings built in the early or mid periods of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.) adopted the shape of ‘ ', the middle hall separates the front and back yards and the gate is designed on the axis. The yard is long and narrow and the small yard is deeper. [Source: State Administration of Cultural Heritage, People’s Republic of China]

Compared with the buildings in Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), they are taller and the materials are used more carefully. The roofs are usually steep, many of which are flush gable roofs. The constructing of the middle hall is stressed and it can be used to go through from the front yard to the back yard. The north hall adopts the style of attic with two or three stories. The layouts of the private houses in the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) tend to be complex. The gate is designed more freely according to the local conditions. The materials standard is clearly higher than before. The north hall has two spacious attics, with the porch post up to the eaves. The downstairs and upstairs are all decorated with beautiful lattice. The woodcarvings in this period become fewer. The wing-rooms of the private houses in Dingcun have three sections divided into two rooms. Against the gable heated kang is built. All the wing-rooms are buildings like attic-the upstairs are used as a storeroom and the upstairs are used for living. There is a square mouth between the gable and the front wall corner and a hanging ladder is used by to go up or down the stairs. The hall is larger and the roof beam links up the main ridge, the short pillar and the fork to make it a triangle stable structure. The bottom of the short pillar is connected with the middle part of the main ridge. It is different from the structure of both in Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) when there are Heta in between and in Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) when there is camel back to sustain.

One kind of the hall is high up to the roof and gives people a feeling of tall and splendour; the other kind is like an attic with the front threshold a dividing line and a layer of board divides the hall into two parts, the upper part is a storeroom. The entire roof is covered with tube-shaped tiles and the mouth of the eaves is designed for water dropping. And there is "Feizi" to sustain. The main ridge is designed on the roof and on both sides of the roof is hanging ridges. The halls in the private residential houses of Dingcun, which were built both in Ming & Qing dynasties, are never used for people to live. The main purpose is to provide places for worship or be used as a storeroom. When there are weddings and funerals, they are places to receive guests. It is absolute different from other places where people have the customs of living in the north house. It is one of the unique local features.

See Separate Article SOUTHERN AND EASTERN SHANXI: COURTYARD HOUSES, ANCIENT VILLAGE CLUSTERS AND MODEL COMMUNES factsanddetails.com

Songyue Pagoda

Songyue Pagoda (Dengfeng, Zhengzhou, Henan Province) is the oldest extant pagoda in China. Built in A.D. 523 during the Northern Wei Dynasty, this Buddhist structure was built with brick rather than wood, which played a big part in its survival over the centuries. Most structures from that period were made of wood and have not survived, although ruins of rammed earth fortifications still exist. In 2010, the Pagoda was named a UNESCO World Heritage List along with other nearby monuments as part of the 'Historic Monuments of Dengfeng in “The Centre of Heaven and Earth”' site. [Source: Wikipedia]

Songyue Pagoda is one of the few intact sixth-century pagodas in China and is the earliest known Chinese brick pagoda. It has changed its shape over time. In the beginning it is believed to have looked more like Indian Buddhist temple, adding on Chinese features as time went by. Its unique many-sided shape suggests that it represents an early attempt to merge the Chinese architecture of straight edges with the circular style of Buddhism from the Indian subcontinent. The perimeter of the pagoda decreases as it rises, a trait seen in Indian and Central Asian Buddhist cave temple pillars and the later round pagodas in China.

The Songyue Pagoda tower is 40 meter (131 feet) high and built of yellowish brick held together with clay mortar. The pagoda has a low, plain brick base, and a charming first story characteristic of pagodas with multiple eaves, with balconies dividing the first story into two levels and doors connecting the two parts. The ornamented arch doors and decorative niches are intricately carved into teapots or lions. At the base of the door pillars are carvings shaped as lotus flowers. The pillar capitals have carved pearls and lotus flowers. After the first story there are fifteen closely spaced roofs lined with eaves and small lattice windows. The densely clustered ornamental bracked eaves on each level are in the dougong style. The wall inside the pagoda is cylindrical and has eight levels of projecting stone supports for what was probably wooden flooring. Underneath the pagoda is an underground series of burial rooms to preserve cultural objects buried with the dead. The inner most chamber contained Buddhist relics, transcripts of Buddhist scriptures and statues of Buddha.

See Separate Article SHAOILIN TEMPLE, ITS FIGHTING MONKS, KUNG FU AND SACRED MOUNT SONG factsanddetails.com

Yingxian Wooded Pagoda

Yingxian Wooded Pagoda

Yingxian Wooded Pagoda (in Yingxian County, Shuozhou City, 70 kilometers south of Datong) is the oldest and tallest wooden pagoda in the world. Built in 1056, the 67-meter (221-foot) -tall structure has withstood storms and earthquakes and is constructed from over 3,500 square yards of wood with using a single nail. Its six gently-sloping tile eaves make the pagoda look like it has six stories but it actually has nine stories inside. What makes the temple so beautiful are its closely spaced windows and doors and elegant balconies.

The Sakyamuni Pagoda of Fogong Temple, located in the northwestern corner of Yingxian County, is a wooden pagoda built in 1056 during the Liao Dynasty (907-1125). Since it was built completely of timber, it has been known popularly as the Yingxian Wooden Pagoda. The octagonal pagoda was built on a four-meter (13.12 feet) stone platform. Standing 67.31 meters (220.83 feet) high, it is the only existing large wooden pagoda in China and also the tallest among ancient wooden buildings of the world. From the exterior, the pagoda seems to have only five stories, yet the pagoda's interior reveals that it actually has nine stories.

Wooden Structures of Liao Dynasty — the Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian County and the Main Hall of the Fengguo Monastery in Yixian County, Liaoning Province — were nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2013.According to a report submitted to UNESCO: the Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian County “ was known as “the first pagoda” during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which means that “there are large numbers of Buddha pagodas in the world, but the Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian County is the first one”. It plays an important role in the history of ancient Chinese architecture. Also, it is the oldest and tallest wooden multi-storey building of the world. This pagoda embodies the wisdom of ancient craftsmen, and it still stands tall after many seismic tests during nine hundred years. It can be described as a miracle in the history of Chinese architecture. The pagoda is called architectural gems by experts in the architectural field both at home and abroad for its long history, unique design and wonderful construction techniques.” [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO]

See Separate Article SHANXI PROVINCE: DATONG, YUNGANG GROTTOES, HENGSHAN AND THE HANGING MONASTERY factsanddetails.com

Wild Goose Pagodas in Xian

Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (in Da Ci'en Temple in the southern part of Xian, six kilometers south of the Bell Tower) is one of the most well-known tourist sight in Xian city. Built in A.D. 652 during the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and set on 190-foot-high hill, it is seven stories high and slightly pyramidal in shape and contains 657 Buddhist scriptures, some brought to China from India in ancient times. Big Wild Goose Pagoda and Little Wild Goose Pagoda (built between 707 and 709) are the most important Tang structures in Xian. They used to dominate the city but now they are lost is sea of concrete block buildings and construction projects.

Originally the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, also called the Greater Wild Goose Pagoda and the Big Wild Goose Pagoda, had five stories. In 701, five more stories were added and it became a 10-story pagoda. Later it was damaged in a war and reduced to seven stories left. In the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the pagoda was renovated and covering it with a layer of bricks. Daci’en Temple is where Buddhist scriptures brought from India by the pilgrim Xuan Zhuang (600-663) were kept and where Xuan Zhuang translated the Buddhist sutras. These sutras occupy a very important position in Chinese Buddhist history. Since ancient times, important religious services have been conducted at Da Ci’en Temple.

Lesser Wild Goose Pagoda (three kilometers northwest of Greater Wild Goose Pagoda, two kilometers south of the Bell Tower) lies within the compound of Jianfu Temple. This Pagoda is smaller than the Greater Wild Goose Pagoda in the Daci’en Temple, hence the name. First constructed in the Jinlong reign (707-710) of Emperor Zhongzong of the Tang Dynasty (618-906), it is a square brick structure with multi-layer eaves. Originally, the Lesser Wild Goose Pagoda had 15 stories, but now it has only 13stories after many earthquakes.

See Separate Article SIGHTS IN XIAN factsanddetails.com

Bell Tower and Drum Tower in Xian

Small Wild Goose PagodaBell Tower (in the center of Xian) is one of the symbol of Xian city. First constructed in the 17th year of the Hongwu reign (1384) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), it is one of the largest, most magnificent and best-preserved architectural structures of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in China. The Bell Tower has three layers of eaves on the external carved beams, and pointed tops on the four corners. The whole building is covered with color patterns, with gilded or colored drawings, painted beams and carved pillars inside. A six-meter-high top plated with gold sits on a glazed louts throne at the top of the Bell Tower, displaying the unique architectural art of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

The Drum Tower and Bell Tower are located near each other in the heart of Xian, and are called sister buildings. The Bell Tower once marked the geographical center of the ancient capital. In 1582, it was moved a kilometer east. The tower is made of brick and timber and almost 40 meters high. During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), Xian was an important military town in Northwest China, a fact reflected in the size and historic significance of its bell tower.

Drum Tower (30 meters west of the Bell Tower) faces south and echoes with the Bell Tower. The Drum Tower got its name from a huge drum in the tower, which was beat at sunset to indicate the end of the day in Ming-era China. Built in the 13th year of the Hongwu reign (1380) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the two-story Drum Tower is 33 meters high, with triple eaves and a hip roof. The Drum Tower in Xian is the largest drum tower in China. The Drum Tower offers a great view of Xian. The drums were used to mark time and on occasion used to raise an alarm in emergency situations. In 1996, a new drum was put into the Drum Tower. It is the biggest drum in China.

See Separate Article SIGHTS IN XIAN factsanddetails.com

Wutaishan Temples

Mt. Wutai embraces a sprawling complex of temples that house some of China's oldest Buddhist manuscripts. Its 53 monasteries house hundreds of monks and nuns. More than 150 temples, many just ruins, are scattered on terraced hillsides and remote mountain tops. The oldest temples dates back to the A.D. first century, when Buddhism arrived in China from India. The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Shuxian Temple is a huge complex with 500 statues of Buddhist figures set among mountains and streams. Xiangtong Temple (A.D. 75), Foguang Temple A.D. 857), with life size clay sculptures, and Nanchan Temple (A.D. 782) are among China's oldest temples.

According to UNESCO: “ The cultural landscape is home to forty-one monasteries and includes the East Main Hall of Foguang Temple, the highest surviving timber building of the Tang Dynasty (618-906), with life-size clay sculptures. It also features the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) Shuxiang Temple with a huge complex with 500 ‘suspension’ statues representing Buddhist stories woven into three-dimensional pictures of mountains and water. Overall, the buildings on the site catalogue the way in which Buddhist architecture developed and influenced palace building in China for over a millennium. [Source: UNESCO]

“Two millennia of temple building have delivered an assembly of temples that present a catalogue of the way Buddhist architecture developed and influenced palace building over a wide part of China and part of Asia. For a thousand years from the Northern Wei period (471-499) nine Emperors made 18 pilgrimages to pay tribute to the bodhisattvas, commemorated in stele and inscriptions. Started by the Emperors, the tradition of pilgrimage to the five peaks is still very much alive. With the extensive library of books collected by Emperors and scholars, the monasteries of Mount Wutai remain an important repository of Buddhist culture, and attract pilgrims from across a wide part of Asia.

See Separate Article Mt. Wutai factsanddetails.com

Foguang Temple

Foguang Temple

Foguang Temple(five kilometers from Doucun, Wutai County,100 kilometers north-northwest of Taiyuan, 150 kilometers south of Datong) is a remarkable wooden Buddhist temple with large intact parts that back to Tang Dynasty (618–907). The major hall of the temple, the Great East Hall, was built in 857. According to architectural records, it is the third earliest preserved timber structure in China. It was rediscovered by the 20th-century architectural historian Liang Sicheng (1901–1972) in 1937. The temple also contains another significant hall dating from 1137 called the Manjusri Hall. In addition, the second oldest existing pagoda in China (after the Songyue Pagoda), dating from the 6th century, is located in the temple grounds. Today the temple is part of the Mount Wutai UNESCO World Heritage site and is undergoing restoration.

The famous Communist-era intellectuals and preservation advocates Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng found Foguang Temple (Temple of Buddha’s Light) after a great deal of searching. Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Their dream had always been to find a wooden temple from the golden age of Chinese art, the glorious Tang Dynasty (618-906). It had always rankled them that Japan claimed the oldest structures in the East, although there were references to far more ancient temples in China. But after years of searching, the likelihood of finding a wooden building that had survived 11 centuries of wars, periodic religious persecutions, vandalism, decay and accidents had begun to seem fantastical. (“After all, a spark of incense could bring down an entire temple,” Liang fretted.) In June 1937, Liang and Lin set off hopefully into the sacred Buddhist mountain range of Wutai Shan, traveling by mule along serpentine tracks into the most verdant pocket of Shanxi, this time accompanied by a young scholar named Mo Zongjiang. The group hoped that, while the most famous Tang structures had probably been rebuilt many times over, those on the less-visited fringes might have endured in obscurity. [Source: Tony Perrottet; Smithsonian Magazine, January 2017]

See Separate Article Mt. Wutai factsanddetails.com

Nanchan Temple

Nanchan Temple (near Doucun on Mt. Wutai, 100 kilometers north-northwest of Taiyuan, 150 kilometers south of Datong) is a Buddhist temple. Its Great Buddha Hall, built in 782 during the Tang Dynasty, is China's oldest preserved wooden building. Not only is it important architecturally it also contains an original set of artistically-important Tang sculptures dating from the period of its construction. Seventeen sculptures share the hall's interior space with a small stone pagoda. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Great Buddha Hall of Nanchan Temple has been dated based on an inscription on a beam. It has endured and escaped destruction during the late Tang Dynasty Buddhist purges of 845, perhaps due to its isolated location in the mountains. Another inscription on a beam indicates that the hall was renovated in 1086 of the Song Dynasty, at which time all but four of the original square columns were replaced with round columns. In the 1950s the building was rediscovered by architectural historians, and in 1961 it was recognized as China's oldest standing timber-frame building. Just five years later in 1966, the building was damaged in an earthquake, and during the renovation period in the 1970s, historians carefully studied the structure piece by piece.

The Great Buddha Hall is a humble timber building with massive overhanging eaves and a three bay square hall that is 10 meters deep and 11.75 meters across the front. The roof is supported by twelve pillars that are implanted directly into a brick foundation. The hip-gable roof is supported by five-puzuo brackets. The hall does not contain any interior columns or a ceiling, nor are there any struts supporting the roof in between the columns. All of these features indicate that this is a low-status structure. The hall contains several features of Tang Dynasty halls, including its longer central front bay, the use of camel-hump braces, and the presence of a yuetai.

See Separate Article Mt. Wutai factsanddetails.com

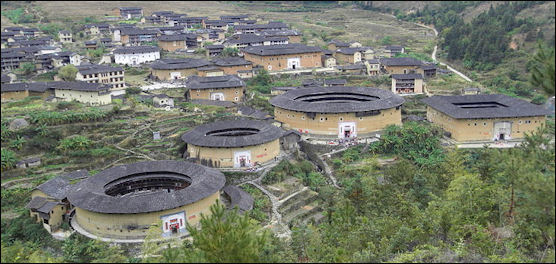

Tulou

Tulou

Tulou (also spelled Tu Lou) is a type of Chinese rural dwellings of the Hakka and Minnan people . Because Hakka people like to live together in remote mountainous and forested regions, they built fortified houses to defend themselves against bandits and wild animals. Tulou (“earth buildings”) are large circular edifices that resemble fortresses in the remote hills of southeastern Fujian Province. They were built by the Hakka after they arrived in Fujian from Henan Province, where they had been persecuted. The tulou are quite impressive and are a popular destination among tourists. There are several thousand of them in Yongding county alone.

Tulou are built from sand, earth and mud and pebbles bound together with glutinous rice and brown sugar. The structures are built on a stone base and supported on wooden poles. Many house more than 100 people. Some house more than 300 people. The Hakka were basically a fishing people. They used the fortified houses in the remote hills to escape persecution. The Tulou's thick walls were packed with dirt and internally fortified with wood. The first Tulou appeared during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and the building style developed over the following dynasties until reaching its current form as found during the period of the Republic of China (1912-1949). Its design incorporates the traditions of Feng shui, showing a perfect combination of unique traditional architecture with picturesque scenery. [Source: Lu Na, China.org, May 9, 2012]

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Since the 12th century, the Hakka and Minnan people in Fujian province have concealed and protected themselves inside tulou, rammed-earth apartment complexes lined with wood-framed rooms facing a communal courtyard. Each clan would build its own tulou over a period of years; some are small, housing only a few dozen people, others can hold more than 500... From the sky, some are shaped like doughnuts. Others take the form of squares and ovals. The structures are so strange and fantastic that American intelligence officers analyzing satellite images during the Cold War initially suspected they were missile silos or part of a nuclear complex. From the ground here in southeastern China, though, it’s clear these fortresses — with thick walls and a single, heavily fortified entrance — were designed not for offense, but for defense. And they’re hardly modern technology.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

See Separate Article TULOU factsanddetails.com

Qufu

Qufu (15 kilometers east of Jining, 550 kilometers south of Beijing) is the home town of Confucius, arguably the most influential human being that ever lived. Known in China as Master Kong or Kong Qiu, he was born and died here and his descendants have continued to live here for 2,500 years after his death. About 20 percent of Qufu's population still bears the Kong surname.

The Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994 According to UNESCO: “Built to commemorate him in 478 B.C., the temple has been destroyed and reconstructed over the centuries; today it comprises more than 100 buildings. The cemetery contains Confucius' tomb and the remains of more than 100,000 of his descendants. The small house of the Kong family developed into a gigantic aristocratic residence, of which 152 buildings remain. The Qufu complex of monuments has retained its outstanding artistic and historic character due to the devotion of successive Chinese emperors over more than 2,000 years.

“The buildings were designed and built with meticulous care according to the ideas of Confucianism regarding the hierarchy of disposition of the various components. In the Ming period many outstanding artists and craftsmen applied their skills in the adornment of the temple, and in the Qing period imperial craftsmen were assigned to build the Dacheng Hall and Gate and the Qin Hall, considered to represent the pinnacle of Qing art and architecture.

The site is special because: 1) The group of monumental ensembles at Qufu is of outstanding artistic value because of the support given to them by Chinese Emperors over two millennia, ensuring that the finest artists and craftsmen were involved in the creation and reconstruction of the buildings and the landscape dedicated to Confucius. 2) The Qufu ensemble represents an outstanding architectural complex which demonstrates the evolution of Chinese material culture over a considerable period of time. 3) The contribution of Confucius to philosophical and political doctrine in the countries of the East for two thousand years, and also in Europe and the west in the 18th and 19th centuries, has been one of the most profound factors in the evolution of modem thought and government.

See Separate Article CONFUCIUS AND THE QUFU AND TAISHAN AREA OF SHANDONG PROVINCE factsanddetails.com

Hongcun

Charming Villages of Southern Anhui

Shexian and Yixian (Yi) counties in southern Anhui (near Huangshan and accessible from Hangzhou by bus and by planes that land at Tunxi airport) are the home of a number charming Ming- and Qing-era villages, the most famous of which are Hongcun and Xidi, which have been designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Travel expert Kate Thompson said: “When you think of the romantic image of China, these villages are it.” UNESCO reports: "Their street plan, their architecture and decoration, and the integration of houses with comprehensive water systems are rare surviving examples of an unspoiled way of life in harmony with nature."

According to the Shanghai Daily: "The traditional villages Hongcun and Xidi preserve to a remarkable extent the appearance of non-urban settlements that disappeared or were transformed during the last century...Since the two villages are close to each other, it's easy to tour both in one day. You can enjoy the natural beauty of one town in the morning mist, while savoring the romantic sunset at the other at day's end. But if you have enough time, I highly recommend that you live in the ancient villages for a while, strolling around, chatting with villagers, trying local delicacies and shopping for antiques...A Chinese writer once observed: "If you want to learn about the life of Chinese emperors, please go to Beijing; if you want to know about civilian life in the Ming and Qing dynasties, please go to Hongcun and Xidi."”

Hongcun and other nearby towns were home to wealthy salt barons as far back as the 14th century. Mostly during the 16th and 17th centuries they built lavish white-walled mansions with delightful courtyards and richly-carved interiors. Shexian is famous for its decorated arches. In Tangmo check out the bonsai trees, pavilions and inscribed tablets in Tanganyuan gardens. Around the town are tea plantations, farms, rice fields and more normal style villages.

See Separate Article CHARMING VILLAGES OF SOUTHERN ANHUI factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP and various books and other publications.

Updated in November 2021