TAIYUAN

Taiyuan (250 kilometers south of Datong and 400 kilometers southeast of Beijing) is the capital and largest city in Shanxi Province, with about 3.7 million people. It is both a gritty, industrial city and a fashionable modern one — with a few historical areas thrown in — thanks to money that flows in from the province's coal wealth. Among the sights in and around Taiyun are the excellent Shanxi Museum, the Jinci Temple and Two Pagodas, the Qiao family compound, where Raise the Red Lanterns was filmed; and the walled city of Pingyao.

Taiyuan (Also known as Bingzhou, Jinyang and Dragon City) is an ancient city with more than 2500 years of urban history, dating back to 497 B.C. It was the capital or secondary capital of the Zhao, Former Qin, Eastern Wei, Northern Qi, Northern Jin, Later Tang, Later Jin, Later Han, and Northern Han Dynasties. Its strategic location and rich history make Taiyuan one of the economic, political, military, and cultural centers of Northern China. Because it was the capital of so many dynasties in China it is called Longcheng (Dragon City).

Located roughly in the centrer of Shanxi, with the Fen River flowing through the central part of the city, Taiyuan is an important manufacturing area of China. It lies in the heart of China's largest coal mining region and one of the important centers of China's chemical industry. Industries are concentrated in the northern part of the city. Tourist Office: Shanxi Tourism Bureau, 282 Yingze Dajie. 030001 Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, Tel. (0)-351-404-7225, fax: (0)-351-407-9215; Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Maps of Taiyuan: chinamaps.org ;

Getting There: Taiyuan is accessible air and bus and lies on the main train line between Beijing and Xian. 3½ hours by bus from Datong Travel China Guide Travel China Guide

See Separate Articles: SHANXI PROVINCE: DATONG AREA, HENGSHAN AND THE HANGING MONASTERY factsanddetails.com ; MT. WUTAI factsanddetails.com ; SOUTHERN AND EASTERN SHANXI: COURTYARD HOUSES, ANCIENT VILLAGE CLUSTERS AND MODEL COMMUNES factsanddetails.com

Transportation in Taiyuan

According to ASIRT: “Local bus transport is well developed. Tourist buses provide transport to popular tourist destinations. Charter buses are available. Taxis are readily available. Fare is based on distance and vehicle type. Registered taxis have a certificate hanging near the meter. City's main roads are generally in good condition. Be alert for construction zones. Local buses leave from the Railway Station Square. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

Taiyuan is a major transportation hub. Main roads serving the city are: 1) Datong-Yuncheng Highway, runs north to south. 2) China National Highway 208 (G208), runs through Taiyuan Economic and Technological Development Zone (TETDZ). G208 is part of Asian Highway 3 (AH3); gives city access to many cities in China and other countries. 3) State Highway No. 307, runs east of TETDZ. 4) Taiyuan-Yuci First-rate Motorway. 5) Can access Taiyuan-Shijiazhuang-Beijing Expressway 2 kilometers from the city's Taiyuan Economic and Technological Development Zone.

Fourteen trunk roads link city with main cities in China. Three ring roads reduce congestion in central districts. Two major roads link the city with Beijing: Beijing-Tianjin Highway and the newer Beijing-Tianjin-Tanggu Expressway. City's Tanggu district, is a large container port. Heavy truck traffic is common on main roads leading to the port.

Taiyuan Metro is under construction, and is expected to start operation around 2020. Seven lines with a total length of 233.6 kilometers and 150 or so station are planned. Line 2 has been under construction since 2013, and is scheduled to open in 2020. Line 1 has been under construction since 2019, and is scheduled to open in 2024. Line 2, crosses the main urban area of Taiyuan in a north-south direction The first phase consists of 23 stations and 23.6 kilometers (14.7 miles) of track between South Renmin Road Station in the south and Xijian River Station in the north. Line 1 will run between Xishan Mining Bureau Station to Wusu Airport Station, and will serve high traffic areas such as Taiyuan West Bus Station, Taiyuan University of Technology, Great South Gate, Wuyi Square, and Taiyuan Railway Station. Line 1 will consist of 24 underground stations and 28.6 kilometers (17.8 miles) of track. Taiyuan Subway Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net ; Website www.tymetro.ltd

Long-Distance Buses generally leave from the long distance bus station. Buses to Datong leave from Taiyuan Railway Station and Taiyuan Coach Terminal. Buses to Pingyao leave from Jiannan Coach Station. Buses to Pingyao Ancient City leave from Coach Station on Yingze Avenue. Buses to Wutai Mountain leave from Taiyuan Long-Distance Bus Station. Airport: Taiyuan Wusu International Airport is located 18 kilometers (11 miles) southeast of city center. TETDZ is 2 kilometers from Taiyuan Wusu International Airport. The airport was upgraded in the late 2000s to serve as a supplemental airport for the Beijing Olympics.

Trains and Train Stations: Tourist trains are available to Beijing, Chengde, Jixian and Tai'an. Passenger trains serving the city include the Taiyuan-Jiaozhou, Beijing- Taiyuan and Shijiazhuang-Taiyuan lines. Main train stations: 1) Tianjin Station, West Station and North Station; 2) Tianjin Station, in city center east of Jiefang Bridge; 3) North Station, in city's Hebei District; 4) West Station, at the northern end of Jinpu rail line; 5) South Station, in city's Hedong District.

Sights in Taiyun

Taiyuan is a modern city with not so many historic buildings in the city but a bunch outside it. The remnants of old Taiyuan can be found west of the central station, north of Fudong Street and close to Wuyi. Chongshan Monastery, Taishan Temple, Fenhe Park; Longtan Park, and Yingze Park are popular tourist destinations in the city.

Twin Pagoda Monastery (in Yongzuo Temple, in the southeast of the city centre near the railway station in Taiyuan) features two 170-foot brick-and-stone pagodas with glazed flying eaves supported by intricately carved brick brackets. Built in 1608, the 13-story pagodas are symbols of Taiyuan. Inside the monetary are stelaes carved by ancient Chinese calligraphers and preserved flowers handed down from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Also known as the Twin Towers, the Twin Pagoda have been regarded as a symbol of Taiyuan for a long time. Yongzuo Temple is famous for its peony garden and martyrs cemetery. Admission: 30 yuan.

Mengshan Giant Buddha is a stone statue built during the Northern Qi dynasty (A.D. 550-557). Initially discovered in a 1980 census, the statue was found to have its head missing. From 2006 to 2008, people constructed a 12-meter tall head for the statue. The site opened to the public in October 2008.

Tianlongshan Grottoes (along the West Mountain range in western Taiyuan) were built over many centuries, being in the northern Qi dynasty (A.D. 550-557) and contains thousands of Buddhist statues and artwork. The grottoes are in poor condituin and have been badly damaged. Many sculptures are gone and now in museums around the world. Researchers at the University of Chicago initiated the Tianlongshan Caves Project in 2013 to pursue research and digital imaging of the caves and their sculptures. Not far from the Tianlongshan Grottoes are the Longshan Grottoes, which is the only Taoist grottoes site in China. The main eight grottoes were carved in 1234~1239 during the Yuan Dynasty.

Shanxi Museum

The Shanxi Museum (West Binhe Road, downtown Taiyuan) is the largest museum and cultural building in Shanxi and one the largest and oldest museums in China. Home to about 400,000 cultural relics and 110,000 old books, it began as the Education Library and Museum of Shanxi, which opened in 1919. Shortly after the beginning Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) the museum’s holdings were heavily damaged and partially moved to Japan.

Exhibits in Shanxi Museum mainly contain cultural relics and cover the Neolithic Age, the Fang State in the Shang Dynasty and of the Jin Dynasty. In addition, cultural relics of the Northern Dynasty, collections of Shanxi pottery, opera relics of the Jin and Yuan dynasties and cultural relics of merchants of the Ming and Qing dynasties are all displayed here. Amongst its important artefacts are those related to Sima Jinlong (d. A.D. 484), including a large number of tomb figurines from his tomb including those made of lead-glazed ceramics. The museum also has a tomb plaque from Sima Jinlong's tomb. Other artefacts related to Sima Jinlong are in the Datong Museum.

The main display of the Shanxi Museum is called the “Soul of Jin (abbreviated name for Shanxi Province)”. It consists of seven historical subjects and five artistic subjects. The historical subjects are: 1) “The Cradle of Civilization”, 2) “The Trace of The Xia and Shang Dynasty”, 3) “The Achievements of the Jin Kingdom”, 4) “The Melting Pot of Different Nationalities”, 5) “The Relics of Buddhism”, 6) “The Hometown of Operas” and 7) “The Shanxi Merchants.” The artistic subjects are 1) “Jades”, 2) “Ancient Chinese Porcelains”, 3) “Ancient Architecture”, 4) “Ancient Chinese Currency” and 5) “Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy”.

Among the featured activities ar the museum are Chinese Shadow Plays and Making Stone Tools. Chinese Shadow Play is an ancient and popular folk drama art in China. In order to popularize this form of art, Shanxi Museum often invites some Chinese Shadow Play artists to perform in the Exhibition Hall. Audiences can not only enjoy the performance, but also have the opportunity to perform shadow play in person. Stone tools are among the oldest of production tools used by human being. They seem easy to make, but they carry rich historical connotations. Visitors can watch archaeologists make stone tools or make stone tools in person, and get to know the basic knowledge of these tools.

Location: No. 13 Northern Section of Binhe Road West, Taiyuan; Hours Open 9:00am-5:00pm, closed Monday. Admission: Since March 2008, free with a valid ID. Getting There: bus No. 865 goes to the museum. Website: shanximuseum.com.cn

Jinci Temple

Jinci (25 kilometers southwest of Taiyuan city) is famous for its temples and Song Dynasty (960-1279) paintings and architecture. Jinci Temple also called Tangshuyu Temple, located in Jinyuan District of southern Taiyuan, dates back to the Zhou Dynasty. In Jinci, there are three treasures: the Nanlao Spring, the Beauty Status and the Queen status. The Flying Bridge Across the Fish Pond was built during the Song Dynasty, which is famous for its cross-shaped structure.

Jinci Temple is a stunning group of shrines, pagodas and towers set among gardens with a 1,400 year history. The Hall of the Holy Mother, the Double Wooden Bridge and the Xiandian Hall are regarded as the most beautiful of the temples’ 100 or so buildings. Each was produced during a different dynasty.

The carved dragons on the wooden pillars of the Hall of the Holy Mother are some of the oldest wood carvings in China. The beams, rails and stone posts of many of the buildings form a lovely lace pattern. The white seven-story Tomb Pagoda features red windows and blue eaves. The "Three Uniques" are the Song Dynasty (960-1279) stone maids, the gurgling Immortal Spring and an ancient cypress tree. Admission: 70 yuan;

Jin Ancestral Temple boasts ancient buildings set in a tranquil environment. Famous for its combination of solemn architecture and skillfully-carved sculptures, it combines buildings, garden, sculpture, wall paintings and tablets. Construction of the temple began prior to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-557) to memorize Shu Yu, the second child of the emperor. Saint Mother Hall, the oldest building in Jin Ancestral Temple, is one of the main attractions of the temple, which is a destination of many visitors. An added draw is that many emperors and poets left tablets here. Among them, the most famous stele was written by Emperor Taizong of Tang Dynasty (618-906) in 646; Admission: 40 yuan (US$6.32) per person.

Diantou Imperial Military Caves

Diantou Caves (2.5 kilometers from ancient Jinyang's city ruins in Taiyuan) refers to a complex of caverns carved into a one-kilometer stretch on the side Mengshan mountainside overlooking a river that runs parallel to the main road running out of Taiyuan,. The entrances to subterranean homes open toward Longshan Mountain across a creek. The foot of Longshan is traced by what was once the only road leading to the ancient Loufan kingdom.

Diantou village once served as an ancient fortress and now looks like a beehive at the foot of a mountain. The caves were likely part of a fortress defending that strategic route. It's said that the founder of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), Emperor Li Yuan, stationed his army here. This is also believed to be the starting point for his expeditions to overthrow the Sui Dynasty (A.D. 581-618) and other warlords. Passageways with doors connect more than 400 caverns, making the complex look like a beehive from the outside but resemble an ant colony inside.

It is thought Diantou's caves were carved to enable imperial soldiers to vanquish invaders without leaving their subterranean fortifications. Li Yang and Sun Ruisheng wrote in the China Daily: “Diantou village's honeycomb of ancient cave dwellings conjures an allure that today draws a diverse cast of characters-adventurers, painters, photographers, architects, military-history fans, archaeologists, filmmakers, historians, monks, Taoists, anthropologists and shepherds. Its function was military-hence, the caverns are all within arrow's reach of the road-since the frontier garrison was long the frontline of skirmishes between agricultural and nomadic civilizations. [Source: Li Yang and Sun Ruisheng, China Daily, December 21, 2015]

“The fortifications were first chiseled into the slopes in the late Western Jin Dynasty (265-316) to protect the ancient city of Jinyang from Hun invaders from the north. It mostly remained a garrison until the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), when the Manchurians subjugated the grasslands' herding tribes. The grottos lodged villagers from then until 2001, when they relocated into modern housing. It was essentially abandoned until Diantou Tourism Development Co manager Li Guihu explored the settlement in 2008.

Rooms and Tunnels in the Diantou Imperial Military Caves

Li Yang and Sun Ruisheng wrote in the China Daily: “A web of tunnels that stretches hundreds of kilometers connects the caves. The altitude and gradient would make it difficult for attackers to enter the caverns. But once inside, getting from chamber to chamber is no easy task. The passageways are punctuated with shelters, peepholes and one-way doors-not to mention secret chambers with air vents used to store grain. One passageway bores deep into a nearby mountain cave that spurts water. While the village is pocked with wells, the mountain spring is believed to have become the primary water source when Diantou was besieged. [Source: Li Yang and Sun Ruisheng, China Daily, December 21, 2015]

“Villagers also used the tunnels to hide from bandits and Japanese invaders during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1937-45). But many became clogged during the peaceful period starting from the 1950s. Li has cleared hundreds of meters of tunnels that connect several main cavities and installed sound-activated lights. Excavations are ongoing.

“Yet while Diantou existed primarily as a military outpost, it also hosted entertainment and religious facilities. A tumbledown theater stage faces collapsed bleachers in the shadow of two ancient locust trees in the west of the village. A "light wall" nearby is bedecked with a candelabrum. Farmers still ignite 365 oil lanterns on the first day of the Lunar New Year and keep them burning until Feb 2 on the traditional Chinese calendar. The ritual seeks blessings for the coming year.

“The wall is directly across from a narrow passageway-only one person can fit at a time-leading to the 700-square- kilometers Zizhulin Temple adjacent to caverns. A drum and a bell tower sprout from the holy site, which was also constructed to withstand incursions via walls, gates and its own tunnel network. The courtyards and surrounding buildings are festooned with elaborate woodcarvings, and images and statues hailing from Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism.

“"The harmonious coexistence of different religions in the temple shows its long history. Different dynasties promoted different religions," tour guide Jia Heping explains. "Feng shui masters praise the design. Its position halfway up the mountain slope facing a steam on one side and a mountain spring on another is particularly auspicious." “Monks continue to run the temple, the crumbling village's only recently reinforced structure. Villagers say the temple's Buddha is particularly effective and has protected the compound for generations. That said, the caves among which the temple was built did the same for Taiyuan-and themselves.”

Qiao Family Compound

Qiao Family Compound (Qiaojiabao Village, Qixian County, 54 kilometers north of Taiyuan) is where Zhang Yimou’s 1991 classic “Raise the Red Lantern” was filmed. This courtyard was built in the late 1700s by the then influential Qiao family. The complex covers an area of 4,175 square meters and consists of six main courtyards and 20 smaller ones, with 313 rooms altogether.

Looking from the pavilion on the southwest corner is a great way to have a bird's-eye view of the entire compound. Beyond the gate is a wall on which is carved Chinese characters, evoking the theme of longevity. Various kinds of red lanterns hang in courtyards, and the carving on the roof is very delicate. It has been featured in many famous Chinese movies and TV series, not only "Raise the Red Lantern," which fully demonstrated the house's character.

Admission: 40 yuan (US$6.32) per person. [Source: China.org] Hours Open: 8:00am to 6:30pm (autumn and winter); 8:00am to 7:30pm (spring and summer). Getting There: Taiyuan Travel Agency has a direct bus to the Qiao Family Courtyard House, costing 80 yuan;

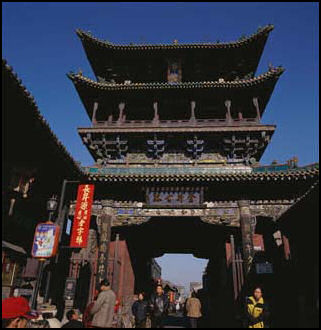

Pingyao

Pingyao

Pingyao (80 kilometers south-southeast of of Taiyun, 715 kilometers southeast of Beijing) is one China's best-preserved medieval towns. Home to 40,00 people and selected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997,it boasts 10-meter-high medieval walls, narrow alleyways and courtyard homes with wooden doors and buildings that used to house 19th century banks, opium dens and brothels. Around the town are millet and cornfields built on the dry, erosion-prone soil of the Loess Plateau.

Pingyao was once a great financial center of China and today is famous for its preservation of many features of northern Han Chinese culture, architecture, and way of life during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Pingyao was founded during the reign of King Xuan (827-782 B.C.) of the Western Zhou Dynasty (1100 to 221 B.C.) but came alive about 500 years ago.. According to UNESCO, "The Old Town of Pingyao is an outstanding example of the Han cities in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, and it retains the traditional features of these periods. Pingyao presents a picture of unusual cultural, social, economic, and religious development in Chinese history."[Source: UNESCO]

“Ping Yao is an exceptionally well-preserved example of a traditional Han Chinese city, founded in the 14th century. Its urban fabric shows the evolution of architectural styles and town planning in Imperial China over five centuries. Of special interest are the imposing buildings associated with banking, for which Ping Yao was the major centre for the whole of China in the 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Lonely Planet described Pingyao as “China’s best-preserved ancient walled town.” Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide UNESCO World Heritage Site site:: UNESCO Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Admission: 125 yuan (US$18) per person; Tel: +86-0354-5690075; Getting There: Pingyao is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main train line between Beijing and Xian. You can take a train from Taiyuan City railway station. It will take you about one and a half hour to get there. You can also take tourist buses from Jiannan bus station in Taiyuan City. Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

Ancient City of Ping Yao

According to UNESCO: The Ancient City of Ping Yao is a well-preserved ancient county-level city in China. Located in Ping Yao County, central Shanxi Province, the property includes three parts: the entire area within the walls of Ping Yao, Shuanglin Temple 6 kilometers southwest of the county seat, and Zhenguo Temple 12 kilometers northeast of the county seat. The Ancient City of Ping Yao well retains the historic form of the county-level cities of the Han people in Central China from the 14th to 20th century.

Founded in the 14th century and covering an area of 225 hectares, the Ancient City of Ping Yao is a complete building complex including ancient walls, streets and lanes, shops, dwellings and temples. Its layout reflects perfectly the developments in architectural style and urban planning of the Han cities over more than five centuries. Particularly, from the 19th century to the early 20th century, the Ancient City of Ping Yao was a financial center for the whole of China. The nearly 4,000 existing shops and traditional dwellings in the town which are grand in form and exquisite in ornament bear witness to Ping Yao’s economic prosperity over a century. With more than 2,000 existing painted sculptures made in the Ming and Qing dynasties, Shuanglin Temple has been reputed as an “oriental art gallery of painted sculptures”. Wanfo Shrine, the main shrine of Zhenguo Temple, dating back to the Five Dynasties, is one of China’s earliest and most precious timber structure buildings in existence.

The Ancient City of Ping Yao is an outstanding example of Han cities in the Ming and Qing dynasties (from the 14th to 20th century). It retains all the Han city features, provides a complete picture of the cultural, social, economic and religious development in Chinese history, and it is of great value for studying the social form, economic structure, military defense, religious belief, traditional thinking, traditional ethics and dwelling form.

The site is special because: 1) “The townscape of Ancient City of Ping Yao excellently reflects the evolution of architectural styles and town planning in Imperial China over five centuries with contributions from different ethnicities and other parts of China. 2) The Ancient City of Ping Yao was a financial center in China from the 19th century to the early 20th century. The business shops and traditional dwellings in the city are historical witnesses to the economic prosperity of the Ancient City of Ping Yao in this period.

Sights in Pingyao

Pingyao boasts a 10-meter-high medieval walls, narrow alleyways and courtyard homes with wooden doors and buildings that used to house 19th century banks, opium dens and brothels. The city walls, streets, houses, shops and temples have been almost kept intact, and the town retains its layouts from the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the city, there are hundreds of well preserved courtyard houses built of black bricks and grey tiles

Pingyao is surrounded by a completely intact six- kilometers (3.73 miles) Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) city wall. As the central axis of the town, the South Street now still keeps its traditional layout and the unique features. The street used to be the home to banks, pawnshops, oil shops, grain shops, wood ware shops, hotels, clothing shops and dye workshops. All of this made Pingyao of one China's leading financial centers during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911);

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: the fortifications “are up to 39 feet thick, 33 feet high and topped with 72 watchtowers. The crenelated bastions, dating from 1370, also enclosed a thriving ancient town, its lane ways lined with lavish mansions, temples and banks dating from the 18th century, when Pingyao was the Qing Dynasty’s financial capital. [Source: Tony Perrottet; Smithsonian Magazine, January 2017]

“A dusty highway now leads to Pingyao’s enormous fortress gates, but once inside, all vehicular traffic is forced to stop. It is an instant step back to the elusive dream of Old China. On my own visit, arriving at night, I was at first disconcerted by the lack of street lighting. In the near-darkness, I edged along narrow cobbled alleys, past noodle shops where the cooks were bent over bubbling caldrons. Street vendors roasted kebabs on charcoal grills. Soon my eyes adjusted to the dark, and I spotted rows of lanterns illuminating ornate facades with gold calligraphy, all historic establishments dating from the 16th to 18th centuries, including exotic spice merchants and martial arts agencies that had once provided protection for banks. One half-expects silk-robed kung fu warriors to appear, tripping lightly across the terra-cotta tile roofs à la Ang Lee.

“The town’s first upscale hotel, Jing’s Residence, is housed inside the magnificent 18th-century home of a wealthy silk merchant. After an exacting renovation, it was opened in 2009 by a coal baroness named Yang Jing, who first visited Pingyao 22 years ago while running an export business. Local craftsmen employed both ancient and contemporary designs in the interior, and the chef specializes in modern twists on traditional dishes, such as the local corned beef served with cat’s ear-shaped noodles.”

Pingyao Banks

The first banks in China opened in Pingyao in the mid 19th century. The banks were opened by merchants that suddenly became wealthy and needed a place to put their money. The banks made loans, offered remittances and checks, which made the merchants wealthier, and made it necessary for banks to open branches in other cities. At its height Pingyao had 22 banks that were instruments in the trade of silk and tea to Russia and wool and leather from Mongolia. The currency was silver ingots. But just as as quickly as whole system got started it collapsed

The banks were regarded as responsible and incorruptible. Trust among businessmen was high. Some of the routine practices — such as loosening up potential clients with prostitutes and opium — would raise eyebrows today. There was also an element of paranoia. The vaults of the banks were vertical pits dug beneath raised platforms that stored piles of silver. Sleeping mats were placed on the platforms and bank employees sat or slept on the mats around the clock. When money was moved it was watched over by guards trained in the martial arts and armed with halberds axes and maces.

One of the main reason that Pingyao is so well preserved is that after the banks collapsed the town was so poor it couldn't afford to modernize or even tear down its medieval walls. It became forgotten and frozen in time, with many families living in courtyard houses made from the old banks, until it started to be restored for tourists beginning in he 1980s. . The first bank to open, called Rishengchnagm ir Sunrise Iver Prosperitum is a museum in the town center. Four other banks have been turned into museums.

Pingyao During the Cultural Revolution

Pingyao survived the Cultural Revolution through an unexpected stewardship of strategic Red Guard leader. Stuart Leavenworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: “In recent years, first-hand accounts have shed some light on this period in Pingyao... and the story starts with Suo Fenqi, who in 1966 was an 18-year-old local leader of the Red Guards, the revolution's shock troops. Fit and handsome, Mr. Suo was born into a farm family that sang songs praising Chairman Mao. His parents had both joined the Communist Party years before the 1949 founding of the People's Republic of China. “I had a good red family background," Suo says. “That's why I was picked to be a Red Guard leader." [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

“Pingyao at that time was a dusty and isolated place, 440 miles southwest of Beijing. Its ancient architecture and courtyard homes were still intact, but its neighborhoods were in transition. One of Suo's duties was to go door-to-door with other Red Guards, seizing hidden gold and other booty, and driving intellectuals and the wealthy from their homes. In and around Pingyao, there were two Red Guard factions: one loosely allied with the military, another allied with Chen Yongui, the Communist party secretary from nearby Dazhai. Mr. Chen was a close ally of Mao, but in 1967 he was being hounded by his rivals. He set up his headquarters in Pingyao's Chenghuang Temple, which dates back to the Northern Song Dynasty of the 1200s. Suo joined him there. |~|

“Chen's faction was badly outgunned by its adversaries, according to Suo, and soon faced a choice: fight or flee. Some advocated retreating to Xian, an ancient city to the South. Suo says he argued for staying and defending Pingyao by fortifying the walls. His argument won the day. Even before the Cultural Revolution, Pingyao's 39-foot-high walls – topped by six dozen watch towers – had fallen into disrepair. At night, peasant farmers would burrow into the walls, hauling away bricks for their houses and pig pens. Suo organized 300 of his men to take back the pilfered building materials and repair the walls. Another 300 people were charged with guarding them and watching out for attacks, he says. |~|

“By early 1969 the two factions, armed with rifles, machine guns, mortars and other weaponry, were girding for a bloody assault. “Personally I did not want to fight, but I had no choice," recalled Suo. “If I had tried to go home (outside the town walls) someone from the other faction would probably have caught me and killed me." At the last moment, Pingyao was granted a reprieve. The Red Army disarmed the Red Guard factions, as it had done elsewhere in China as Mao sought to restore order in the country. The ancient walls of Pingyao had endured. But it had had nothing to do with historical preservation, says Suo. “The real reason Pingyao's walls survived was to protect our faction." “ |~|

Preservationist Helps Save Pingyao in the Cultural Revolution

Stuart Leavenworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: “During the early years of the Cultural Revolution a quiet preservationist named Li Youhua embedded himself with Suo and his allies. A skilled artist and calligrapher, Mr. Li lived with Chen and Suo in the Chenghuang Temple, but he kept his head down because of his family background; his grandfather had been accused of being a collaborationist during the Japanese occupation. Li died in 1999, but he left behind a trove of letters, drawings, and photographs of his restoration work in Pingyao and other cities. In 2002, his son Li Shujie assembled these papers into a pair of books, which tell the story of a relentless preservationist. According to his son, Li was appalled by the Red Guards’ destruction of antiquities, but he could not openly protest. “It was too dangerous," says Mr. Li. Carefully and quietly though, his father saved what he could. [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

“Outside Pingyao, Red Guards had started smashing the Shuanglin Temple, an old Buddhist temple that had been rebuilt in 1571. According to his son, Li snuck into the temple and brought out a colorful sculpture from the Hall of One Thousand Buddhas. Later he returned it to the temple. Local peasants also rallied to save some of Shuanglin's sculptures and artwork, says Suo. “Unlike the intellectuals," he says, “the farmers were not afraid of the Red Guards." |~|

“When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, Li Youhua joined what later became Pingyao's cultural heritage department, where he continued to fight to preserve remnants of China's past. Pingyao's biggest employer was a tractor factory near the north wall of the city. A flood damaged the factory's dormitory in 1977, and officials proposed rebuilding it on top of the wall. Li protested, and then quietly organized political opposition to the project, says Li Shujie. Eventually the provincial Communist party secretary intervened, saving the north wall from a misguided alteration." |~|

Tourism in Pingyao

Stuart Leavenworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: “Every day, hordes of Chinese and foreign visitors crowd into this medieval county seat. They stroll down lantern-festooned lanes, admire Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) architecture and climb the steps to town walls that date back 640 years...Over the last two decades mass tourism has transformed Pingyao, a town of 50,000 people that became a World Heritage Site in 1997. Crowds jostle to enter its temples and finance museums, which tell of Pingyao’s banking history. The entire town has been made over “to create an atmosphere of staged authenticity,” according to Shu-Yi Wang, an urban development scholar in Taiwan who has written several reports on Pingyao. [Source: Stuart Leavenworth, Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 2016 |~|]

“Despite the town’s Disneyland-like atmosphere, ghosts from the Cultural Revolution linger. On the old tractor factory’s brick walls, for example, revolutionary slogans can still be seen urging workers to “learn from Daqing,” an industrious oil city in northern China that Mao admired. At the Chenghuang Temple, tour groups meander through the leafy courtyards, which boast impressive statuary, urns, and wood carvings. Many of them are modern replicas; most of the temple’s antiquities were destroyed at the start of the Cultural Revolution, according to Suo and others. At the main altar, though, a faded but exquisite mural remains. On a recent morning a tour guide led two visitors to that altar. During the Cultural Revolution, she said, someone brushed a coat of white water-based paint over the mural to hide it from rampagers. Later the whitewash was removed, revealing the mural intact underneath.

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Many Chinese are now visiting Pingyao.” The hotelier Yang Jing said, “At first, most Chinese people found Pingyao too dirty. They certainly didn’t understand the idea of a ‘historic hotel,’ and would immediately ask to change to a bigger room, then leave after one night. They wanted somewhere like a Hilton, with a big shiny bathroom.” She added with a smile: “But it has been slowly changing. People are tired of Chinese cities that all look the same.”

Conservation of Pingyao

Tony Perrottet wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Liang and Lin’s spirits hover over the remote town today. Having survived the Red Guards, Pingyao became the site of an intense conservation battle in 1980, when the local government decided to “rejuvenate” the town by blasting six roads through its heart for car traffic. One of China’s most respected urban historians, Ruan Yisan of Shanghai’s Tongji University — who met Lin Huiyin in the early 1950s and attended lectures given by Liang Sicheng — arrived to halt the steamrollers. He was given one month by the state governor to devise an alternative proposal. Ruan took up residence in Pingyao with 11 of his best students and got to work, braving lice, rock-hard kang beds with coal burners beneath them for warmth, and continual bouts of dysentery. Finally, Ruan’s plan was accepted, the roads were diverted and the old town of Pingyao was saved. His efforts were rewarded when Unesco declared the entire town a World Heritage site in 1997. Only today is it being discovered by foreign travelers.

“Although Prof. Ruan Yisan is 82 years old, he returns every summer to monitor its condition and lead teams on renovation projects. I met him over a banquet in an elegant courtyard, where he was addressing fresh-faced volunteers from France, Shanghai and Beijing for a project that would now be led by his grandson. “I learned from Liang Sicheng’s mistakes,” he declared, waving his chopsticks theatrically. “He went straight into conflict with Chairman Mao. It was a fight he couldn’t win.”

“Instead, Ruan said, he preferred to convince government officials that heritage preservation is in their own interest, helping them improve the economy by promoting tourism. But, as ever, tourism is a delicate balancing act. For the moment, Pingyao looks much as it did when Liang and Lin were traveling, but its population is declining and its hundreds of ornate wooden structures are fragile. “The larger public buildings, where admission can be charged, are very well maintained,” Ruan explained. “The problem is now the dozens of residential houses that make up the actual texture of Pingyao, many of which are in urgent need of repair.” He has started the Ruan Yisan Heritage Foundation to continue his efforts to preserve the town, and he believes a preservation spirit is spreading in Chinese society — if gradually.”

Qixian: Pingyao Less Developed Sister City

Qixian (20 kilometers north-northwest of Pingyao) is town that is similar to Pingyao but some is more authentic except that its three-kilometer, six-meter-high square city wall is gone. Li Yang And Sunruisheng wrote in China Daily: “It was once a quadrant of North China's most prosperous banking cluster. But the settlement has been all but forgotten by outsiders. That's partly because the neighboring ancient town of Pingyao's early and advanced tourism development left Qixian in its shadow. “Yet Qixian is more like Pingyao's sister city, rather than a lost cousin. [Source: Li Yang And Sunruisheng, China Daily, December 21, 2015]

“Still, there are sibling differences. One is Qixian remains mostly intact-save for its walls, four embrasure towers and four barbican gates. These barricades' bricks were cannibalized to rebuild houses in the 1950s, following the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1937-45) and the civil war from 1946 to 1949. It has also largely so far escaped renovation, unlike Pingyao, which was renovated and repackaged as a tourist destination starting a decade ago.

“Only a few shops and eateries have sprung up to serve Qixian's visitors. Residents lead quiet lives. They believe the settlement's feng shui blesses them. Two perpendicular flagstone streets intersect in the center of downtown. The quadrants these 10-meter-wide thoroughfares spliced into districts had their own schools and wells. Government and military departments were constellated throughout, as are 11 temples, each with its own Buddha or god that overseas a particular realm of residents' life.

“The town is laced with over 30 narrow lanes-some so constricted, two people have to turn sideways to pass each other. The tangled lanes' narrowness and configuration is believed to make it impossible for ghosts or evil spirits to prowl. Courtyard gates are also festooned with thousands of stone exorcism tablets. But the alleyways' arrangement protects residents from not only the supernatural but also such forces of nature as frigid northern winds and sandstorms. The superstitious may also argue the geomantic layout accounts for Qixian's historical success as a finance center.

“Over 500 years, the town and neighboring Yuci, Taigu and Pingyao developed into North China's most prosperous conurbation.

“Qixian's affluence peaked from the start of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) until the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) because China's tea trade with Central and West Asia, and Europe passed through Shanxi before heading through Mongolia. In the late 19th century, the four counties had a total of around 40 large national banks that did business around the country. Shanghai had only 18. Around a dozen families ran hundreds of shops in Qixian, where they built grand courtyards and mansions. Their descendants attribute their ancestors' success to their masterful fusion of Confucian honesty and commerce. The 20th-century flourishing of China's maritime trade and the Japanese invasion devastated the town's businesses.

“But their legacy still stands as more than 1,000 courtyards. About 40 are massive mansions, or former banks, shops or bodyguard agencies. Some have been converted into museums on the local financial industry, architecture or martial arts practiced by armed escorts. Two flank houses on either side, plus a two-story building at the end, border courtyards. The compounds are usually arranged three to five in a row and are linked by gates, creating mini mazes inside the large labyrinth that is the town as a whole. Structures are built with grey bricks, black tiles and wood. Facades are adorned with tile carvings. And images from Chinese legends and religions are embossed on wood, stone and brick. Houses' rooftops slant to dribble precipitation into the courtyards, as rainfall is considered a symbol of wealth.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020