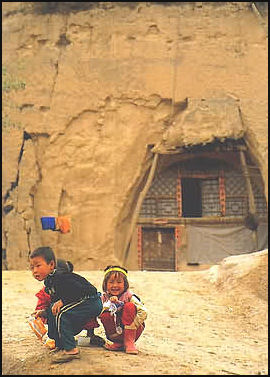

CAVE HOMES IN CHINA

Some 30 million Chinese still live in caves and over a 100 million people reside in houses with one or more walls built in a hillside. Many of the cave and hill dwellings are in the Shanxi, Henan and Gansu provinces. Caves are cool in the summer, warm in the winter and generally utilize land that can not be used for farming. On the down side, they are generally dark and have poor ventilation. Modern caves with improved designs have large windows, skylights and better ventilation. Some larger cave have over 40 rooms. Others are rented out as three-bedroom apartments.

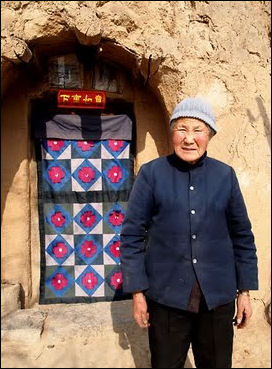

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Many Chinese cave-dwellers live "in Shaanxi province, where the Loess plateau, with its distinctive cliffs of yellow, porous soil, makes digging easy and cave dwelling a reasonable option. Each of the province's caves, yaodong, in Chinese, typically has a long vaulted room dug into the side of a mountain with a semicircular entrance covered with rice paper or colorful quilts. People hang decorations on the walls, often a portrait of Mao Tse-tung or a photograph of a movie star torn out of a glossy magazine. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, March 18, 2012]

Sometimes the cave homes are unsafe. In September 2003, 12 people were killed when a landslide buried a group of cave houses in the village of Liangjiagou in Shaanxi Province. Most of the dead were in one cave house that was hosting a party for family members after the birth of a son.

See Separate Articles HOMES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL HOUSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOUSING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOUSES IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POSSESSIONS, ROOMS, FURNITURE, AND HIGH-END TOILETS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HIGH REAL ESTATE PRICES AND BUYING A HOUSE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Yin Yu Tang pem.org ; House Architecture washington.edu ; House Interiors washington.edu; Tulou are Hakka Clan Homes in Fujian Province. They have been declared a World Heritage Site.Hakka Houses flickr.com/photos ; UNESCO World Heritage Site : UNESCO Books: "Houses of China" by Bonne Shemie ; “Yin Yu Tang: The Architecture and Daily Life of a Chinese House” by Nancy Berliner (Tuttle, 2003) is about the reconstruction of a Qing dynasty courtyard house in the United States. Yun Yu Tamg means shade-shelter, abundance and hall.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Houses of China” by Bonnie Shemie (1996) Amazon.com; “China's Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation” by Ronald G. Knapp Amazon.com; “Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation” by Ronald G. Knapp , A. Chester Ong , et al. Amazon.com; “Chinese Houses: A Pictorial Tour of China’s Traditional Dwellings” by Chen Congzhou, Pan Hongxuan, et al. Amazon.com; “Yin Yu Tang: The Architecture and Daily Life of a Chinese House”by Nancy Berline Amazon.com; “Chinese Culture - Siheyuan Residence By Ke Yang Amazon.com

History of Cave Dwellings

According to the research of ancient architects, more than 4000 years ago Han people living on the northwest Loess Plateau had a custom of "digging a cave and living in." People of this region continue to live in cave dwellings in the provinces or autonomous regions of the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~]

The caves have an important role in modern Chinese history. After the Long March, the famous retreat of the Communist Party in the 1930s, the Red Army reached Yanan, in northern Shanxi Province, where they dug and lived in cave dwellings. In "Red Star Over China," writer Edgar Snow described a Red Army university that "was probably the world's only seat of 'higher learning' whose classrooms were bombproof caves, with chairs and desks of stone and brick, and blackboards and walls of limestone and clay." In his cave dwelling in Yan'an, Chairman Mao Zedong led the War of Resistance against Japan (1937-1945) and wrote many “glorious: works, such as "On Practice” "Contradiction Theory" and "Talking about the Protracted War." Today these cave dwellings are tourist sights. ~

Chinese President Xi Jinping lived for seven years in a cave when he was exiled to Shaanxi province during the Cultural Revolution. "The cave topology is one of the earliest human architectural forms; there are caves in France, in Spain, people still living in caves in India," said David Wang, an architecture professor at Washington State University in Spokane who has written widely on the subject. "What is unique to China is the ongoing history it has had over two millenniums."

Types of Cave Dwellings

Inside a cave house

Cave dwellings are divided into three types: 1) earth cave, 2) brick cave, and 3) stone cave. Cave dwelling do not occupy cultivated land or destroy the topographical features of the ground, benefitting the ecological balance of an area. They are cool in summer and warm in winter. Brick cave dwelling are generally made up of bricks and built where the earth and hills are composed of relatively soft yellow clay. Stone cave dwellings are commonly built against mountains facing the south with stones selected by their quality, lamination and color. Some are carved with patterns and symbols. ~

The earth cave is comparatively primitive. These are generally dug in a naturally vertical broken precipice or abrupt slope. Inside caves the rooms are arch shaped. The earth cave is very firm. The better caves protrude from the mountain and are reinforced with brick masonry. Some are connected laterally so a family can have several chambers. Electricity and even running water can be brought in. "Most aren't so fancy, but I've seen some really beautiful caves: high ceilings and spacious with a nice yard out front where you can exercise and sit in the sun," one cave home owner told the Los Angeles Times.

Many cave homes consist of a large dug-out square pit with a well in the middle of the pit to prevent flooding. Other caves are chiseled out of the sides of cliff faces comprised of loess — a thick, hard, yellow rocklike soil that is ideal for making caves. Rooms chiseled into hard loess usually have an arched ceilings. Those made in softer loess have pointed or supported ceilings. Depending on what materials are available, the front of a cave is often made of wood, concrete or mud bricks.

Modern Cave Homes in China

inside another cave home Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, In recent years, architects have been reappraising the cave in environmental terms, and they like what they see. "It is energy efficient. The farmers can save their arable land for planting if they build their houses in the slope. It doesn't take much money or skill to build," said Liu Jiaping, director of the Green Architecture Research Center in Xian and perhaps the leading expert on cave living. "Then again, it doesn't suit modern complicated lifestyles very well. People want to have a fridge, washing machine, television." [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, March 18, 2012]

Liu helped design and develop a modernized version of traditional cave dwellings that in 2006 was a finalist for a World Habitat Award, sponsored by a British foundation dedicated to sustainable housing. The updated cave dwellings are built against the cliff in two levels, with openings over the archways for light and ventilation. Each family has four chambers, two on each level.

"It's like living in a villa. Caves in our villages are as comfortable as posh apartments in the city," said Cheng Wei, 43, a Communist Party official who lives in one of the cave houses in Zaoyuan village on the outskirts of Yanan. "A lot of people come here looking to rent our caves, but nobody wants to move out."

The thriving market around Yanan means a cave with three rooms and a bathroom (a total of 750 square feet) can be advertised for sale at $46,000. A simple one-room cave without plumbing rents for $30 a month, with some people relying on outhouses or potties that they empty outside. Many caves, however, are not for sale or rent because they are handed down from one generation to another, though for just how many generations, people often can't say.

People Who Live at Cave Homes in China

another Shanxi cave home

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Like many peasants from the outskirts of Yanan, China, Ren Shouhua was born in a cave and lived there until he got a job in the city and moved into a concrete-block house. His progression made sense as he strove to improve his life. But there's a twist: The 46-year-old Ren plans to move back to a cave when he retires. "It's cool in the summer and warm in the winter. It's quiet and safe," said Ren, a ruddy-faced man who works as a driver and is the son of a wheat and millet farmer. "When I get old, I'd like to go back to my roots." [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, March 18, 2012]

Ma Liangshui, 76, lives in a one-room cave on a main road south of Yanan. It is nothing fancy, but there is electricity — a bare bulb dangling from the ceiling. He sleeps on a kang, a traditional bed that is basically an earthen ledge, with a fire underneath that is also used for cooking. His daughter-in-law has tacked up photographs of Fan Bingbing, a popular actress.

The cave faces west, which makes it easy to bask in the late afternoon sun by pulling aside the blue-and-white patchwork quilt that hangs next to drying red peppers in the arched entrance. Ma said his son and daughter-in-law have moved to the city, but he doesn't want to leave. "Life is easy and comfortable here. I don't need to climb stairs. I have everything I need," he said. "I've lived all my life in caves, and I can't imagine anything different."

Xi Jinping’s Cave Home Years

Xi Jinping is the leader of China. Liangjiahe (two hours from Yenan, where Mao finished the Long March) is where Xi spent seven years during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s. He was one of millions of city youths "sent down" to the China countryside to work and "learn from the peasants" but also to reduce urban unemployment and reduce the violence and revolutionary activity of radical student groups. .[Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

Liangjiahe is a tiny community of cave dwellings dug into arid hills and cliffs and fronted by dried mud walls with wooden lattice entryways. Xi helped to build irrigation ditches and lived in a cave home for three years. "I ate a lot more bitterness than most people," Xi said in a rare 2001 interview with a Chinese magazine. “Knives are sharpened on the stone. People are refined through hardship. Whenever I later encountered trouble, I’d just think of how hard it had been to get things done back then and nothing would then seem difficult.” [Source: Jonathan Fenby, The Guardian, November 7 2010; Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, November 15, 2012]

Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times: “Turning a leader’s former home into a tableau for propagating his political-creation myth has a venerable precedent in the People’s Republic. Back in the 1960s, Mao’s birthplace, Shaoshan, was turned into a secular shrine for slogan-chanting Red Guards who looked on modern China’s founder as a nearly godlike figure. The devotion at Liangjiahe falls far short of the fervent cult of personality that Mao ignited. Even so, Mr. Xi stands out for turning his own biography into an object of adoration, and zeal. Neither of Mr. Xi’s recent predecessors as leader, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, could tout a similarly dramatic tale of coming of age in a dim, flea-infested cave. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, October 8, 2017]

See Separate Article XI JINPING'S EARLY LIFE AND CAVE HOME YEARS factsanddetails.com

Beijing’s Underground Apartments

In December 2014, NPR reported: “In Beijing, even the tiniest apartment can cost a fortune — after all, with more than 21 million residents, space is limited and demand is high. But it is possible to find more affordable housing. You’ll just have to join an estimated 1 million of the city’s residents and look underground. Below the city’s bustling streets, bomb shelters and storage basements are turned into illegal — but affordable — apartments. [Source: NPR, December 7, 2014 ^|^]

Annette Kim, a professor at the University of Southern California who researches urbanization, spent last year in China’s capital city studying the underground housing market. “Part of why there’s so much underground space is because it’s the official building code to continue to build bomb shelters and basements,” Kim says. “That’s a lot of new, underground space that’s increasing in supply all the time. They’re everywhere.”

But “there’s a stigma to living in basements and bomb shelters, as Kim found when she interviewed residents above ground about their neighbors directly below. “They weren’t sure who was down there,” Kim says. “There is actually very little contact between above ground and below ground, and so there’s this fear of security.” ^|^

“In reality, she says, the underground residents are mostly young migrants who moved from the countryside looking for work in Beijing. “They’re all the service people in the city,” she says. “They’re your waitresses, store clerks, interior designers, tech workers, who just can’t afford a place in the city.” Kim says there’s a range of units, from the dark and dingy to the neatly decorated.

Life in Beijing’s Underground

USC’s Annette Kim told NPR the “apartments go one to three stories below ground. Residents have communal bathrooms and shared kitchens. The tiny, windowless rooms have just enough space to fit a bed.“It’s tight,” Kim says. “But I also lived in Beijing for a year, and the city, in general, is tight.” With an average rent of $70 per month, she says, this is an affordable option for city-dwellers. But living underground is illegal, Kim says, since housing laws changed in 2010. [Source: NPR, December 7, 2014 ^|^]

Beijing-based photographer Chi Yin Sim has documented life under the city in a collection called China’s “Rat Tribe.“ The first basement-dweller she met was a young woman, a pedicurist at a salon, who lived with her boyfriend. The couple lived two floors below a posh Beijing apartment complex. Sim’s photos show just how tiny these units really are. The couple sits on their bed, surrounded by clothes, boxes and a giant teddy bear. There’s hardly any room to move around. “The air is not so good, ventilation is not so good,” Sim says. “And the main complaint that people have is not that they can’t see the sun: It’s that it’s very humid in the summer. So everything that they put out in their rooms gets a bit moldy, because it’s just very damp and dank underground.” ^|^

“Sim says residents adapt to the close quarters. “At dinnertime you can hear people cooking, you can hear people chit-chatting in the next room, you can hear people watching television,” she says. “It’s really not so bad. I mean, you’re spending almost all your day at work anyway. And you’re coming back, and all you need is a clean and safe place to sleep in.” ^|^

“Kim says life underground “is especially hard for the older residents, some of whom have been down there for years. “They’re hoping that their next generation, their children, will be able to live above ground,” Kim says. “It’s this sense of longing and deferring a dream. And so it makes me wonder how long this dream can be deferred.” But despite the laws against living underground, and the discomfort and shame associated with it, Kim says it’s still a very active market. For hundreds of thousands of people, it’s the only viable option for living in, or under, Beijing.” ^|^

Ant People Living in Beijing's Bomb Shelters

“As speculators and increasing demand drive up Beijing's real estate prices, those who cannot afford the rent are going underground — literally,” Andreas Lorenz wrote in Der Spiegel. “Hundreds of cellars and air-raid shelters are being rented out as living spaces in the Chinese capital. Two years ago, 27-year-old sports teacher Dong Ying relocated from a small city in the north-eastern province of Heilongjiang to Beijing ro seek better opportunities. Working at several fitness clubs she earns around 3,000 yuan (around $500 to $675) per month, a sum she would never have earned doing similar work in her hometown. And here she can enjoy the big city. "I am happy," says the young woman, who is wearing a pink Nike sports shirt. "I love my work, and I feel free."[Source: Andreas Lorenz, Der Spiegel, December 24, 2010]

“But there is a severe flaw in her Beijing lifestyle. Dong Ying lives, literally, underground. The only accommodation she can afford is a tiny room in the cellar of an apartment building. Every month she pays the equivalent of $68 for the room, around 15 percent of her income. Other tenants must live even further down, on the cellar's second level, where the rent is even cheaper. A bed, a small cupboard and a desk just fit into Dong Ying's barren room. A communal toilet and bathroom are at the end of the hallway. Anyone living here must eat out every day because any kind of kitchen is prohibited for safety reasons.” Still, Dong Ying can find something positive to say about her home: "The house management is OK. The corridor is clean."

“Dong Ying is one of hundreds of thousands of Chinese sentenced to a life underground — migrant workers, job seekers, street vendors. All those who can't afford life above ground in Beijing are forced to look below. Dong Ying's room is one of around a hundred similar dwellings under a modern apartment block on the outskirts of the Beijing district of Chaoyang. While the wealthier residents enter the building, then go right or left to an elevator, the underground dwellers head past a cellar for bicycle storage, and then downstairs. There's no emergency exit.”

“Generally it's not the people living in the apartments above who rent out their cellar spaces: It tends to be apartment managers who put the unused spaces to work. In doing so, they tread close to breaking rental laws. Some even rent out official air-raid shelters— hich is actually totally prohibited. The demand for underground accommodation may even rise in the near future. The Beijing city administration recently gave permission to level dozens of outlying villages in order to make room for new living and business areas.

Thousands of migrant workers live in those villages, often in primitive conditions. The citizens of Beijing call them the "ant people" because of the way they live on top of one another. Demolishing the villages will leave them with few options. They will either find accommodation farther outside the city, or, if they want to live close to their workplaces, they will have to go underground.

Even families live in the cellars. “Wang Xueping, 30 is... trying to push her baby carriage out of the basement of Building 9 in the Jiqing Li residential complex in central Beijing. Two months ago, she and the child moved from Jilin province in northeastern China to join her husband, who's been driving cabs in Beijing for three years. Now all three of them live in a cellar room that is 10 square meters (108 square feet) in size. “The main thing is that we can all live together, as a family,” she said...Meanwhile, fitness trainer Dong Ying has had good luck. She's moved cellars, into a room with a small shaft that allows a little daylight in. And she has a new boyfriend, who has just bought himself a new apartment. If they get married, Dong Ying's days underground will end.

Image Sources: University of Washington except cave homes, Beifan.com , and Beijing suburb, Ian Patterson; Asia Obscura ;

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021