HUTONGS

courtyard house

Hutongs are the mazelike old neighborhoods made up of traditional quadrangle courtyard homes lined up along on narrow streets and alleys and often built in accordance with the principals of feng shui.In the pre-Mao-era, many residences were occupied by single extended family units and had spacious open air courtyards. But after Communists came to power the houses were divided and occupied by several families and the courtyards were filled with shanties. In many cases a house occupied by one family before Mao was occupied by six or seven after. In part because of this, the hutongs are very compact and tightly packed, The Dazhalan hutong area near Tiananmen Square contains 57,000 residents jammed into 114 hutongs that cover an area less than a quarter mile square.

Hutong means lane and alley, smaller than a street. It is a passage formed by lines of siheyuan (courtyard houses) where many Beijing residents live. One hutong connects with another, and siheyuan connects with siheyuan, to form a block, and blocks join with blocks to form the whole city. Famous Beijing hutongs include: Nanluoguxiang, Yandaixiejie, Mao'er Hutong and Guozijian Street.

Hutong refers to both the traditional winding lanes and traditional old city neighborhoods. Hutongs are comprised mostly of alleys with no names that often twist and turn with no apparent rhyme or reason. They are fun to get lost in but near impossible to find anything in. The tile-roofed houses lie mostly behind gray brick walls and are unified into neighborhoods by public toilets and entranceways that people share. Heating is often provided by smoky coal fires that occasionally asphyxiate house occupants. Public toilets and showers are sometimes hundreds of meters away from the people who use them.

Chaney Kwak wrote in the Washington Post: “Beijing is famous for a palace that’s a city unto itself, a Great Wall once purported to be visible from space, and Brobdingnagian architectural experiments by design giants such as I.M. Pei and Zaha Hadid. Traversing one city block can mean a hazy hike between mega malls and rows of traffic congestion; standing in Tiananmen Square is an exercise in humility, its vastness a reminder of how insignificant we are in this crowded world. [Source: Chaney Kwak, Washington Post, April 4, 2013]

“But the imposingly scaled side of Beijing fades into the gritty beige air as I stand in the middle of a maze created by the city’s old hutongs, or back alleys. In the narrow space that runs between the chipped brick walls of one-story dwellings, a scrappy kid kicks around a dusty ball while a mutt watches and yawns; a vegetable hawker pedals leisurely by, pulling a full cart while belting out Mandarin tunes.

“Beijing used to have many such intimate neighborhoods brimming with siheyuans, or courtyard mansions, that were eventually partitioned into apartments for the proletariat. Today, skyscrapers sprout all over the city like weeds, and beltways proliferate like age rings, plowing over these traditional communities. But in the heart of the central Gulou area, an enclave of sloping eaves and winding hutongs has escaped the ubiquitous bulldozers, defying the Chinese capital’s growth spurt. That these hutongs have maintained their ancient anatomy doesn’t mean that the area is ossified in the past, however.”

A good book on hutong life is Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Web Sites: Wikipedia ;China Highlights China Highlights ; Travel China Guide

See Separate Articles HOMES IN CHINA: TRADITIONAL HOMES AND MAO-ERA HOUSING factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF THE OLD NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Early Hutong History

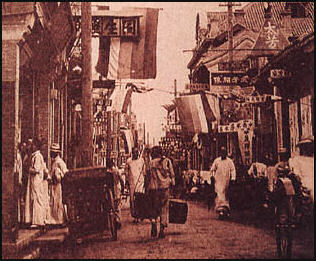

19th century Beijing

The term hutong, according to one source, is derived from the Mongolian term for a passageway between yurts (tents). According to another source it is derived from the Mongolian word hottoh (“water well”). The idea here I guess is that where there was a spring or well, there were residents or a community. The word hottog became hutong after it was introduced into Beijing during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), when China was absorbed into the Mongol Empire. Most of Beijing remaining hutongs date to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). By one estimate there was once 4,550 hutongs. Today, maybe 2,000 remain. According to the Chinese government here were 459 hutongs in the Ming Dynasty and 978 hutongs in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The present number, the government says, is 1,316 in the urban and suburban districts of Beijing.

The history of the hutongs can be traced back to the Yuan Dynasty. After the establishment of the Yuan authority, the nobles were pleased to be awarded with certain pieces of land as feudal estates. They actively built houses and courtyards which were arranged in order around water wells. The passages between houses were left to allow for light and ventilation and a convenient right-of way.

Though these countless passages crisscrossed the old capital like a chessboard, there were only 29 of them called Hutongs. Because city planning was very strict at that time, the roads which measured 36 meters wide were called main streets, the 18-meter wide roads were named side streets and those nine meters or less were designated as Hutongs. In the Ming (1368 – 1644) and the Qing (1644 – 1911) Dynasties, city planning was less strict. Stallholders squeezed in the residential districts, which made the Hutongs differ in width from over six meters to less than one meter. The basic appearance of Hutongs was generally formed during these periods with many having just one entrance.

During China’s dynastic heyday, the emperors planned the city and arranged the residential areas according to the etiquette systems of the Zhou Dynasty (1100 to 221 B.C.). At the center of the metropolis was the Forbidden City, surrounded in concentric circles by the Inner City and Outer City. Citizens of higher social status were permitted to live closer to the center of the circles. The aristocratic hutongs of those days were located just to the east and west of the imperial palace. The lanes were orderly, lined by spacious homes and walled gardens. Further from the palace and to its north and south were the commoners’ hutongs, where merchants, artisans and laborers lived and worked.[Source: China.org April 5, 2004]

The residences lining the hutongs, whether grand or humble, were generally siheyuan, complexes formed by four buildings surrounding a courtyard. The large siheyuan of high-ranking officials and wealthy merchants often featured beautifully carved and painted roof beams and pillars and carefully landscaped gardens. Commoners’ siheyuan were far smaller in scale and simpler in design and decoration. The hutongs are, in fact, passageways formed by many siheyuan of varying sizes, all arranged closely together. Nearly all siheyuan had their main buildings and gates facing south for better lighting; so that the majority of hutongs run from east to west. Between the main hutongs, many tiny lanes ran north and south for convenient passage.

Later Hutong History

Around the turn of the 20th century, the Qing court was disintegrating, foreign influences were having a huge impact on people’s lives and China’s dynastic era was coming to an end. The traditional arrangement of the hutongs was also affected. Many new hutongs, built haphazardly and with no apparent plan, began to appear on the outskirts of the old city; while the old ones lost their former neat appearance. The social stratification of the residents also began to evaporate, reflecting the collapse of the feudal system. During the period of the Republic of China (1911-1948), society was unstable, fraught with civil wars and repeated foreign invasions. The city of Beijing deteriorated, and the conditions of the hutongs worsened. Siheyuan previously owned and occupied by a single family were subdivided and shared by many households, with additions tacked on as needed, built with whatever materials were available. The 978 hutongs listed in Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) records had swelled to 1,330 by 1949, with nearly 5,000 tiny alleys threading their way between the legitimate hutongs.

In the decades since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs have disappeared, replaced by the high rises and wide boulevards of today’s Beijing. Many citizens have left the lanes where their families resided for generations, resettling in comfortable apartment buildings with modern amenities. In Xicheng District alone, nearly 200 hutongs out of the 820 it held in 1949 have disappeared. And the Beijing Municipal Construction Committee says that in 2004, some 250,000 square meters of old housing — 20,000 households — will be demolished in 2004, which means that many more will disappear. However, many of Beijing’s ancient hutongs still stand, and a number of them have been designated protected areas. The old neighborhoods survive today, offering a glimpse of life in the capital city as it has been for generations. [Source: China.org April 5, 2004]

The hutongs districts remained largely untouched in the early years of Communist rule in the 1950s. At that time much of Beijing’s population lived in hutongs. And the wealthy hutong neighborhoods were mostly in northern Beijing and the poorer ones were in south of the Forbidden City. Starting in the 1960s as Beijing's population grew housing shortages developed and several families began squeezing into courtyard houses meant for one family. Short of space the courtyards were filled with kitchens and sheds. Once open spaces became warrens of rooms, in the process of transforming many hutongs in slums that were avoided by middle class Chinese who lived in government housing.

In the late 1980s, the government allowed private businesses to set up shop in the hutongs in hopes of stimulating the economy and creating jobs. In recent years hutongs have been torn down to make way for new developments and many existing hutongs have been gentrified. More than 1,000 courtyard properties in dozens of hutongs were renovated or destroyed in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Today, only a small fraction of an estimated 3,700 hutongs remain. Former hutong residents have largely scattered to apartment complexes on the city’s outskirts. Under a three-year plan launched in 2017 to clean up 1,674 hutongs, — more than two-thirds of all existing hutongs, most of them in congested central Beijing — the municipal government targeted illegal construction.

Everyday Life in the Hutongs

Beijing street life

Hutongs are comprised mostly of alleys with no names that often twist and turn with no apparent rhyme or reason. They are fun to get lost in but near impossible to find anything in. The houses lie mostly behind gray brick walls and are unified into neighborhoods by public toilets and entranceways that people share. Heating is often provided by smoky coal fires that occasionally asphyxiate house occupants. Public toilets and showers are sometimes hundreds of meters away from the people who use them.

The walled courtyard houses have traditionally kept private life behind the walls but fed a lively public life that flowed into the alleys. During the day old men sell vegetables; children study on desks outside their homes; small time cobblers and fruit vendors go about their business; and beauty-parlor-massage-parlors welcome customers into old collapsing courtyard homes. In the evening many residents gather in the alleys to eat dinner, talk or play some game. Even in the middle of winter friends gather to chat in the streets and street vendors make their rounds.

Jessica Meyers wrote in the Los Angeles Times: ““These traditional neighborhoods, like the one I live in behind Beijing's most iconic Buddhist temple, comprise a mix of elderly residents, foreigners on a quest for "character," nostalgic hipsters and migrants who sleep in the back of their 10-foot noodle shop. Nearby is Beixinqiao San Tiao, a lively hutong crammed with butcher shops, old men watching the world from a stool, and a seafood restaurant that washes its clams in the street. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times , April 19, 2017]

Many of the alleys are too narrow for cars and the commercial buildings are too small for anything larger than family-owned shops. By small parks there are exercise stations with bars and pendulums and hoops and things like that, where older people like to gather and hang out and occasionally do a couple of exercises. In the morning residents scamper with their chamber pots to the public toilet. Vendors arrive mid morning with the three-wheeled carts, each crying the product or service the are selling: toilet paper, coal, recycling or knife-sharpening

Day in the Life of a Hutong

Singapore-native Benlim Chiow Ang wrote in The Beijing Review: “Just after 7 in the morning, I embark on a typical routine for the day. My work place, which is a vocational school located along a hutong, is a 10-minute leisure ride on my time-tested bicycle from my dormitory in another hutong. The 10-minute journey captures the essence of hutongs as Beijingers go about their daily business. [Source: Benlim Chiow Ang, Beijing Review, January 20, 2009]

”I have to navigate delicately on my bicycle between the parked cars along the hutong and four-wheeled vehicles approaching me from all directions, all aspiring to be the first to get out from the hutong maze. In no time, car drivers and bicycle riders were caught in the congested narrow hutong. Their adrenalin levels are up and running and a shouting match is about to commence. The sleepy kids seated at the rear of their mums' bicycles are obviously oblivious to the commotion as their mothers try to outdo other vehicles to get their kids to preschools on time. High school students and vocational students on their respective bicycles are also competing with other users for premium space in this narrow hutong.

”At one corner, a group of high school students jostled for breakfast with one particular mobile snack shop stubbornly refusing to give way to oncoming vehicles. Along the way, it is not unusual to see the trail of damage left on the wheels of parked vehicles as the dogs lift their hind legs in the canine morning ritual, getting tacit approval from their owners. It has been said that the dog population in Beijing has reached astronomical levels. A concerted campaign by all stakeholders to send a strong message to dog owners to be civil-minded would certainly enhance the hutong environment. During the ride, I have to be careful about bumping into people still in their pajamas, carry buckets of water as they make their way to the public lavatory or WC as it is known amongst the locals. Neighbors exchanging pleasantries in their standard Beijing-Chinese accent can be heard as I continue on to my work place. At each hutong junction, I have to slow down in order not to clash with vehicles coming from my blind side. Finally, I reach my destination, Beijing Finance and Economics School in Fensiting Hutong and begin my day teaching work as a business-subject teacher.

”In the mid-afternoon after finishing my day work, I embark on my return journey. Unlike the early morning journey, the lazy-afternoon trip seems a bit more peaceful. A dozen of rickshaw riders with tourists in tow is a common sight in this stretch of Baochao Hutong, which is considered a tourist attraction as it seems to be the most comprehensive blend of old residential houses and business stores such as hair salons, grocery stores, small-renovation shops, bicycles repairs shops and restaurants. Taking a quick peek at the windows of the restaurants in my slow moving but trusted bicycle, I can see waiters, waitresses and chefs having their well-deserved afternoon nap. It is not uncommon to see lost tourists asking locals for direction as they try to navigate themselves through the winding alleyways. The improvement to the public lavatories and other facilities along the hutong over the years is a testament to the economic prosperity of China as a whole. I am glad to be here to witness the history in the making.”

Traditional Courtyard Houses in China

A traditional Chinese house is a compound with walls and dwellings organized around a courtyard. Walls and courtyards are built for privacy and protection from fierce winds. Inside the courtyard, whose size depends on the wealth of the family, are open spaces, trees, plants and ponds. In the inner courtyards of rural homes, chickens are often kept in coops and pigs are allowed to roam inside small enclosures. Covered verandas connect the rooms and dwelling.

Rural homes are typically built on one, two, three or four sides of an enclosed courtyard. Sometimes one family owns all the units around the courtyard, sometimes different families do. Most houses have peaked tile roofs although slate roofs are common and thatch is still used in some places. In high density areas multistory houses built in rows along streets predominate. They have a courtyard in the front or the back and have a flat roof. In commercial areas families often live upstairs and have a shop or business or animals or storage in the bottom floor.

Many urban homes are one-story courtyard homes too. A typical courtyard house in a hutong in Beijing has an entrance on the south wall. Outside the front door are two flat stones, sometimes carved like lions, for mounting horses and showing off a family's wealth and status. Inside the front door there is freestanding wall to block the entrance of evil spirits, which only travel in straight lines Behind it is the outer courtyard, with servant's quarters to the right and left. The family traditionally lived in the inner courtyard towards the back of the north wall. Painted pillars are polished to a high sheen by builders who had first apply several layers of pigs’ blood.

Siheyuan: North China's Courtyard Houses

Traditional hutongs are made up largely of courtyard residences, known as siheyuan. Siheyuan (a square courtyard with houses on four sides) is the traditional, local-style dwelling of northern urban Han people. According to historical analyses, they appeared and developed more than 2,000 years ago in the Han Dynasty and were used extensively by the Tang Dynasty. The size of Siheyuan varies. Large ones have gardens and pavilions inside. Large or small, the roof is built with the axis as the center. The Siheyuan is built to quiet and closed to the outside world. It feels cool in summer and warm in winter. Beijing Siheyuan are mostly built along of lanes and streets. Large families living in such residences were described in Lao She's "Si Shi Tong Tang" and Ba Jin's "Family". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

In a traditional northern Chinese courtyard house, the family residence is situated in the north of the compound and faces south. There are often of inner and outer yards. The outer yard is horizontal and long with a main door that opens to the southeast corner, maintaining the privacy of the residence. Through the main door to the west in the outer yard are guest rooms, servants' room, a kitchen and toilet. North of the outer yard, through an exquisitely shaped, floral-pendant gate, is the spacious square main yard. The principal room in the north is the largest, erected with tablets of "heaven, earth, the monarch, kinsfolk and teacher," and intended for family ceremonies and receiving distinguished guests."Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China /=]

The left and right sides of the principal room are linked to aisles that were inhabited by family elders. In front of the aisle is a small, quiet corner yard often used as a study. Both sides of the main yard have a wing room that served as a living room for younger generations. Both the principal room and wing rooms face the yards, which have front porches. Verandahs link the floral-pendant gate and the three houses, where one can walk or sit to enjoy the flowers and trees in the courtyard. Sometimes, behind the principal room, there is a long row of "Hou Zhao Fang (back-illuminated rooms) that served as either a living room or utility room. /=\

Beijing's Siheyuan is cordial and quiet, with a strong flavor of life. The courtyard is square, vast and of a suitable size. It contains flowers and is set up with rocks, providing an ideal space for outdoor life. Such elements make the courtyard seem like an open-air, large living room, drawing heaven and earth closer to people's hearts; this is why the courtyard was most favored by them. The verandah divides the courtyard into several big and small spaces that are not very distant from each other. These spaces penetrate one another, setting off the void and the solids, and the contrast of shadows. The divisions also make the courtyard more suited to the standards of daily life. Family members exchanged their views here, which created a cordial temperament and an interesting atmosphere. /=\

In fact, the centripetal and cohesive atmosphere of Beijing's Siheyuan, with its strict rules and forms, is a typical expression of the character of most Chinese residences. The courtyard's pattern of being closed to the outside and open to the inside can be regarded as a wise integration of two kinds of contradictory psychologies: On one hand the self-sufficient feudal families needed to maintain a certain separation from the outside world; on the other, the psychology, deeply rooted in the mode of agricultural production, makes the Chinese particularly keen on getting closer to nature. They often want to see the heaven, earth, flowers, grass and trees in their own homes. Certain appropriately sized square courtyards of Beijing's Siheyuan help absorb sunshine in the wintertime. In areas south of Beijing, where the setting sun in the summer is quite strong, the courtyards have become narrow and long on the north-south side to reduce the amount of sunshine. /=\

Hutong Development

Torn down neighborhood

In recent years many hutongs have been torn down to make way for concrete high-rises and commercial buildings. According to one estimate only 350 of the original 6,000 hutongs that stood in Beijing in the 1990s are left and that number is expected to shrink to 25 in the not too distant future. Even protected hutongs are being bulldozed.

The government claims that the hutongs are overcrowded, dangerous and unsanitary. Some houses are more than 100 meters away from the nearest toilet. Others lack plumbing and have no way to put out fires that could result in dozens of deaths. Some hutongs were removed to make way for 2008 Olympic development.

Few hutong residents see their neighborhoods as historic districts. Many are not disinclined to move as long as they receive adequate compensation that allows them to find another affordable place to live. In some cases the old courtyard houses have been divided so many times that people in them are living in rooms the size of closets with neighbors so close they can almost reach out and touch them. Many hutong residents have been moved to apartment complexes and new homes that look ugly but have all the modern conveniences. In many ways the people who lament the loss of the hutongs the most are Western tourists, old timers who were comfortable in the hutongs and residents who did not receive adequate compensation.

Jessica Meyers wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “China's communist government grants temporary land rights to individuals, but exercises far broader authority over property than its counterpart in the United States. Officials have valid reason to seek improvements. High-voltage lines dangle into the street like willow trees; a tarp covers holes in some roofs. Two motorcycles recently plowed into each other in front of a convenience store. Neither could see past the parked cars and delivery carts that blocked the T-shaped intersection. Residents "can have a better quality of life once the project is done," said Hu Xinyu, managing director of the nonprofit Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center. "The hutong will once again be a pleasant place to live." [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times , April 19, 2017]

Members of the intelligentsia — particularly the advocate Hua Xinmi and the journalist Wang Jun — have taken up the hutong development issue and attracted Western attention. Sensitive to foreign criticism with the Olympics Games approaching, the government drafted a conservation plan and designated 25 protected historic zones in the city center. In recent years the demolition of the hutongs has slowed as result of efforts by preservationists and developers tapping into the gentrification market.

Gentrification of the Hutongs

Some of the last remaining courtyard yard houses have bought up by gentrification developers who install modern toilets and other amenities and selling the houses to upper class Chinese or wealthy foreign investors. Some developers and buyers have spent millions remodeling their houses and installing things like saunas, exercise rooms, modern kitchens and underground garages. But as this is taking place the neighborhoods are losing their identity and character and the fabric of everyday life that hold them together. With single rich families occupying the houses, people no longer spill into the streets

Chaney Kwak wrote in the Washington Post: “The more I talk to these internationally oriented entrepreneurs, the more it seems that all roads lead to Joel Shuchat, the Canadian who opened the boutique hotel Orchid two years ago. I follow the address, which takes me to the end of a trash-strewn passageway off Baochao Hutong. Once I get buzzed in through the frosted door, I’m in the fragrant lobby that doubles as a chic bar, where hirsute men in skinny jeans and pixie girls in vintage-ish attire are hanging out to lazy down-tempo beats. I’d believe it if you told me that I was back in the Mission in San Francisco. I look around and realize that, for the first time since landing in China, I’m the only Asian in the room. [Source: Chaney Kwak, Washington Post, April 4, 2013]

“Expressive and energetic, Shuchat has an encyclopedic knowledge of all the internationally owned businesses in the area. Yet he seems as weary of as knowledgeable about the transformation of this neighborhood. Baochao Hutong “used to be exclusively residential,” he says almost wistfully. Now, “tons of businesses have evolved.” When I ask him about the media attention his hotel has brought to the alley, he rolls his eyes and throws his hands in the air. “Who hasn’t covered us?” he asks, annoyed.

“Perhaps his exasperation is born of fear. While Baochao Hutong, with its mom-and-pop enterprises, remains relatively low-key, it’s showing signs of imminent gentrification, with a tapas bar and intriguing shops such as Triple Major, a clothier inside a former apothecary. Shuchat must know, however, that his own hotel and its Western guests herald the force that may destroy the very authenticity that his establishment touts as its appeal. I realize that Beijing reminds me of Brooklyn and San Francisco not because of the superficial trappings of hipsterdom — beards! brews! specialty shops beyond the neighbors’ reach! — but because it’s running into the very same pitfalls of gentrification that you find around the world.”

Hutong’s Arty Residents

The hutongs have attracted a lot of expats and arty types. Chaney Kwak wrote in the Washington Post: “Perhaps the lower cost of living in the hutongs has been a driving force behind the explosion of enterprises here. The rent is low, “so it gives people a chance to experiment while allowing the neighborhood to grow organically,” says Shannon Bufton, the Australian architect who co-owns Serk, an airy space on Beixinqiao San Tiao Hutong that has doubled as a bike store and a watering hole since opening in June 2012. “Beijing is crying out for creative people. Chinese consumers have disposable income.” Still, most of the clients who buy his upmarket wheels are, Bufton says, expats. [Source: Chaney Kwak, Washington Post, April 4, 2013]

“Floor-to-ceiling front windows separate Serk’s minimalist wood-and-concrete decor from the debris and chaos outdoors. But when the weather warms up, the store removes the front panes, blurring the border between the store and the hutong. Recently, Bufton’s bar patrons have become equally split between foreign and Chinese revelers.

“Bufton and his partner, Liman Zhao, are hardly alone in infusing the Chinese capital’s quaint nooks with youthful optimism. The past couple of years have seen an influx of globally minded entrepreneurs opening pint-size bars and discreet boutiques that are part Berlin and part Brooklyn.

“In 2010, American emigre Carl Setzer’s Great Leap stamped Doujiao Hutong with the surefire mark of hipsterdom: a microbrewery. Meanwhile, Rose Lin Zamoa transformed her private kitchen into the Caribbean eatery Jamaica Me Crazy in Cheniandian Hutong last October, just as the Taiwanese studio Good Design Institute opted to open its first store not on its home turf in Taipei but in Baochao Hutong. The rent may be low, but these hutong shops’ products tend to be pricey. The three-month-old S.T.A.R.S. boutique stocks Parisian haute couture, but its converted-mansion store is catty-corner from a public toilet shared by hutong residents who don’t have private bathrooms.

Demolition of the Hutongs

In Beijing, Shanghai and elsewhere, old homes, old building and entire old tightly-knit neighborhoods have been torn down to may way for skyscrapers, offices complexes, shopping malls and other forms of modern development. Tens of thousands of urban residents have been forced to move or have been evicted.

Some residents in the Qiamen district of Beijing have been forced out of their houses while police officers carted away their lights and furniture. Residents there were paid about $1,000 per square meter, about a fifth of what developers plan to charge for rebuilt old-style courtyard houses.

Jessica Meyers wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Authorities destroyed scores of hutong communities before the 2008 Olympics, when China sought to present a modern image to the world. Only a third of the city's thousands of hutong remained a decade ago, according to a survey by the Beijing Institute of Civil Engineering and Architecture. Newer accounts vary, but preservationists believe they've dropped into the hundreds. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times , April 19, 2017]

“The renovations, even if well intentioned, fuel backlash because they encapsulate the uneasy tension between old Peking and the modern capital. "The government itself is wrestling with the question of what the hutongs mean in Beijing," said Jeremiah Jenne, a historian who leads walking tours through the alleyways. "Are they an eyesore or a tourist attraction?"

In Beijing, 60 areas were demolished in 2010 mainly to erect high-rise complexes and greenbelts. More than 180,000 residents were affected and there were a number ugly clashes. People who fought authorities over their evictions have ended up in jail. Lawyers who have represented have been threatened by government officials. To protest the destruction of hutongs in Beijing some residents have chosen to kill themselves rather than be relocated. There have been a few cases of self immolations.

Springtime is Hutong Destruction Time in Beijing

Jessica Meyers wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Beijing's chapped, arctic winters give way to spring nearly overnight. Peach trees bloom, the sky turns from charcoal to blue, people linger outside. And buildings get demolished. The construction — and destruction — begins every year around this time, alongside allergies and the peeling of layers. Buzz saws sub in for alarm clocks, and the city is invaded by men wearing yellow hard hats. But this spring is more frenzied than usual. The government has embarked on a renovation project in Beijing's centuries-old courtyard alleyways known as hutong. These narrow streets — filled with dumpling shops, gossipy grandmothers and communal bathrooms — have largely succumbed to high-rises and haphazard renovations with concrete walls etched to look like aged bricks. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times , April 19, 2017]

“Officials want to create an "orderly, civilized and beautiful street environment" in these remaining alleys by rooting out unlicensed buildings and reducing clutter. This makes them legal and probably safer. It also threatens to erode the city's soul. "This is the spirit of Beijing," hutong dweller Yang Jingxian, 30, said one evening as a three-wheeled cart clattered past, carrying doors, plywood, bricks and cement. Transforming them makes the city look "like everywhere else."

“That central locale one recent morning looked as though it had just survived a bomb. Construction equipment wedged into the lane, which echoed with the clang of metal and toppling bricks. Siding poured out of corner stores. Workers fought the rising dust with hoses, and guards eyeballed piles of debris that stacked up to their shoulders. The next morning, bikes sped down a nearly unrecognizable road, lined with redesigned concrete buildings sealed off from the street and sanitized of the chaos that once defined it. “"My heart hurts," said Ma Jiang, 32, who watched crews knock out the windows and brick up the entrance to his pocket-size Hippo Bar. A sign now points around the corner to a side door, and customers no longer spill into street. Like others on the lane, he's been chased inside. Ma took the transformation in stride. At least, he said, the government paid for it.

“The city management commission in charge of the effort declined to comment.“These ancient alleys are victims of China's rapid change. My landlord was born in the small courtyard house I rent, known as a siheyuan. The family, we're told, occupied the whole compound until officials carved it into sections after the communist takeover and distributed them to multiple families. “My neighbors take great pride in the century-old, peeling wood door that opens to our equally old one-story homes. We talk about it a lot, along with the weather. “Either way, come spring, they're a reminder that very little in Beijing is permanent.

“The hammers last weekend started before 6 a.m. Our neighbor across the street had decided to remodel his home. He stood in his pajamas and directed the construction crew to hack the front wall, a comfortably clad maestro amid the rubble.“His house will stand stories tall, a new beacon in our ancient neighborhood.”

Demolition of Beijing's Drum Tower Homes

In December 2012, AFP reported: “Large numbers of hutong homes, some of them dating back to the Qing dynasty, will be demolished around the Drum and Bell Towers — a tourist hotspot in Beijing's historic centre — to make way for a large plaza. Notices for the "destroy and evict" project are plastered throughout the quarter. Besides protecting the historic legacy of the capital, the project is also aimed at restoring and repairing old and dilapidated buildings, the notices said. [Source: AFP, December 14, 2012 ^]

“Destroying old homes in central Beijing has particular sensitivity. Critics say new development projects rob the capital of its cultural legacy. "We have been hearing this was going to happen for years, but now that the notices are up there is not much you can do but leave," said souvenir shop seller Ma Yong."When I first saw the notices I felt nothing but despair." Besides having her rented shop torn down, Ma's small home nearby, where she lives with her retired husband, will also be flattened. ^

“Residents must negotiate compensation with the newly set up "destroy and evict" office near the Bell Tower, with compensation beginning at around 40,000 yuan (US$5,800) per square meter. Between 130 and 500 homes are to be destroyed, state press reports said. "A lot of people are opposed to the campaign, 40,000 yuan per square meter is too cheap, especially with the price of housing in Beijing sky-rocketing," said the manager of a coffee shop near the Drum Tower, who gave her surname only as Wang. "People are already asking for 150,000 yuan per square meter," she said. Others said they were happy with the compensation. "We took the money," said Zhou Li, 51, who was to move out to the suburbs with his elderly parents this weekend after living most of his life near the Bell Tower. ^

Developers Demolish Famed Architects' Home

Liang Sicheng (1901-1972) and Lin Huiyin (1904-1955) are regarded by some as Beijing’s original preservationists. Liang wrote “The History of Chinese Architecture”. After the Communists came to power Liang and Lin helped design the new national emblem and were asked to invent a new style of Chinese architecture. Among Liang’s most famous designs is the Monument to the People’ Heroes that stands at the center of Tiananmen Square. In the end Liang’s ideas where incompatible with those of the Communists. Liang tried by persuade Mao Zedong to save Beijing’s towering walls, which encircles the capital. The request was rejected and the walls were torn down and replaced with a quasi ring road. Liang’s idea of establishing a new capital outside of Beijing so Beijing’s architecture could be preserved was also rejected. In February 2012, under the cover of night and the Chinese New Year, a team armed only with hand tools demolished the sprawling 400-square-meter courtyard house at No. 24 Bei Zong Bu Alley, where Laing and his wife lived from 1930 to 1937, to make way for modern development.

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, Developers in Beijing have demolished the home of architects Liang Sicheng and his wife Lin Huiyin, whose appreciation of China's ancient buildings and their devotion to preserving its heritage made them two of the country's most revered architects. Liang is known as the father of modern Chinese architecture, and much of his and Lin's most important work was carried out while they were living in the courtyard house in Beizongbu Hutong in the 1930s. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 30, 2012]

The demolition took place over the lunar New Year, despite the fact it is rare for labourers to work during the festival, raising suspicions that the company hoped to avoid publicity. A Beijing official told state news agency Xinhua the firm wanted to prevent the residence being harmed during last week's holiday, apparently referring to the fireworks which are let off. Other Chinese media quoted an unidentified developer as saying that the demolition was "in preparation for maintaining the heritage site" because the buildings were in bad condition. But heritage protection activist Zeng Yizhi — who alerted city officials to the demolition — said they should have repaired the buildings. "Liang and Lin made such a great contribution to the protection of Chinese ancient buildings. If their home can be torn down, then developers can do the same thing to hundreds of other ancient houses in the country," he told China Daily.

He Shuzhong, founder of the Beijing Cultural Heritage centre, said the early 20th century building was the intersection between the study and preservation of cultural relics, as pioneered by the couple, and the dangers posed by rapid urban development. Experts and campaigners are also angry because they hoped they had staved off the threat to Liang and Lin's home in 2009, when the district government approved its destruction and it was partially knocked down. Following a public outcry, the state administration of cultural heritage intervened and the site was designated a permanent cultural relic, meaning official approval was required for demolition.

Liang and Lin wrote a seminal work on Chinese architecture, listed relics in need of protection during wartime, designed the national emblem of the People's Republic of China and worked on the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. Liang and his colleague Chen Zhanxiang urged the Communist government to build an entirely new city when it decided to make Beijing the capital of the new republic. He believed it was the best way to preserve its ancient buildings. But officials rejected that plan and most of the old city has vanished forever.

Chinese media named the developers of the Beizongbu site as Fuheng Real Estate, a subsidiary of state-owned China Resources. An employee at the China Resources Group said it was a holding company and the matter should be raised with the China Resources Land Company. The city administration of cultural heritage said it would not comment as the Dongcheng district cultural committee was responsible for the case. Officials there did not answer calls. But district heritage officials admitted that the demolition had not been approved by the city-level authorities, Xinhua reported.

Dongcheng officials told reporters they had ordered developers to rebuild the house — a measure dismissed by campaigners as meaningless. "Building a replica only makes things worse. So I suggest that the government build a monument or a park on the original site in memory of Liang and Lin," Chen Zhihua, a professor at Tsinghua University's school of architecture and a former student of the couple, told China Daily.

Lin died in 1955 after an illness. Liang was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and died in 1972. His second wife Lin Zhu said she was very sorry to hear of the demolition. "I don't think his contribution and work is being properly valued and respected," she said, adding that Liang's later home on the Tsinghua University campus was also worth preserving but was in poor condition at present.

Hutong Clean-Up Targets Small Businesses and Migrants

Muyu Xu and Ryan Woo of Reuters wrote: “Chinese capital is sanitizing its ancient hutong alleyways, home to millions of migrants workers and thousands of small businesses, bulldozing illegal constructions and forcing shops, bars and tiny courtyard restaurants to relocate or go under. As part of guidelines unveiled in April, authorities have started to brick in doors of properties along the narrow passageways, many of which date back to the 13th century. They have also cracked down on illegal shopfronts to restore the original facades. Traditionally a courtyard property has only one entrance. That means shops on a property are not allowed to create or maintain additional entrances. On top of that, authorities have stopped issuing new commercial licenses in Beijing's most ambitious clean-up of the hutongs, where some buildings are crumbling and unsafe. And current licenses will not be renewed.The municipal government says it is trying to eradicate an "urban disease". [Source: Muyu Xu and Ryan Woo, Reuters, May 8, 2017]

“Business owners have been seen taking photos of their shopfronts and bidding them goodbye. For some, they are saying farewell to the old city. "The most appealing part of Beijing is about to disappear," said Titi, the owner of a clothing store in Fangjia hutong, famous for its bars and vintage stores. Shopkeepers in Fangjia complained that they had not been given enough time before their stores were bricked in. Some had no choice but to hold flash clearance sales during a recent three-day public holiday to get rid of stock. Residents and businesses are given from five to 15 days to rectify unapproved construction before "the authorities enforce mandatory demolition with no obligation to compensate any losses", according to notices posted on the walls of many hutongs. "I am not against government policy, but you (the authorities) have to give us some time to take care of our business," said the owner of a Fangjia Mexican snack bar.

“It was unclear what will happen to properties that are restored but left empty. Most hutong properties are leased to migrant workers. Official data shows the number of migrant workers has risen fivefold over the past 18 years, peaking at 8.2 million in 2015. That growth has slowed due to new population controls which aim to cap the number of people at 23 million by 2020. Beijing's population now is about 21.7 million. While there is no official word linking the revamp to efforts to curb population growth, some migrant workers, who run everything from convenience stores to hair salons to dumpling restaurants and even a British-themed pub, are convinced they are a target. "There is no single high-rise building that was not built by migrant workers," construction worker An said. "Now the city doesn't need us to build more buildings, so we are being kicked out."

“An and his wife may have to move back to eastern Shandong province after their kitchen was torn down. "What can we do? We've to go back home if the authorities are determined to kick us out," said An, who declined to give his full name for fear of repercussions. An and his wife have rented a 10 square-meter (100 square-foot) room in Xilou hutong for three years. Their children and grandchildren visit every day, but they never stay overnight as the room is too small.

“The hutong revamp is overseen by Beijing's new mayor, Cai Qi, who said city authorities should "dare to play hardball" when taking down unapproved projects and unsafe construction. The press department at the Beijing municipal government office could not immediately comment on the current hutong revamp. The Beijing Administration for Industry and Commerce did not reply to a fax seeking comment. In Wenchang hutong near Beijing's financial center, the owner of a pancake shop, who gave her name as Su, is worried about the future. "My store is of the same age those of fancy buildings nearby, but mine has to retire early," said Su, who left central Henan province for Beijing more than two decades ago.

Development Saving the Hutongs?

On how development is helping one hutong keep going, Chaney Kwak wrote in the Washington Post: “Ironically, it’s this immense commercialization that has ensured the survival of Nanluoguxiang, says Yuan Yuan, a 31-year-old Beijing native. Together with her boyfriend, Omar Maseroli, she runs a year-old Bolognese trattoria named Mercante in Fangzhuanchang Hutong, just 10 minutes — but also a world away — from the bustle of Nanluoguxiang. “Every day you see a new opening,” Maseroli says. “We’re trying to turn the hutong into something modern that can work in today’s Beijing, so obviously it has to become commercial in some way. At the same time, we want to keep the neighborhood in its shape.” [Source: Chaney Kwak, Washington Post, April 4, 2013]

“In January, Yuan says, the government announced yet another planned session of chai, the word meaning “to tear down” that has become synonymous with razing hutongs, in the adjacent area behind the 15th-century Drum Tower. The two-story landmark serves as a guiding point for lost pedestrians, but it will be dwarfed by new arrivals once the area is bulldozed. At a moment’s notice, Yuan and Maseroli’s own beloved quarter may disappear like so many others.

“When I step out into the darkness, vendors are packing up their vegetable carts and meat stalls as residents shuffle home for dinner. People like Maseroli and Yuan are walking a tightrope. If their enterprises become too successful, the hutongs will become carbon copies of Nanluoguxiang — chain shops and endless traffic squeezing out the original inhabitants and atmosphere. But if these winding paths and old quadrangles remain as they are, the development-hungry city may haul out the wrecking ball at any moment. Either way, change seems inevitable.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in May 2020