URBAN LIFE IN CHINA

About 64 percent of Chinese now live in urban areas (compared to 81 percent in the U.S.), Only 11 percent of China's population inhabited urban areas in 1950. In 2010, more than half the population still lived in rural areas. The Chinese government aimed for 60 percent of the population to live in cities by 2020 in part to turning millions of rural dwellers into consumers, that would drive the world's second-largest economy into the world's largest economy. [Source: China 2020 Census, Ben Blanchard, Reuters, June 12, 2015]

About 64 percent of Chinese now live in urban areas (compared to 81 percent in the U.S.), Only 11 percent of China's population inhabited urban areas in 1950. In 2010, more than half the population still lived in rural areas. The Chinese government aimed for 60 percent of the population to live in cities by 2020 in part to turning millions of rural dwellers into consumers, that would drive the world's second-largest economy into the world's largest economy. [Source: China 2020 Census, Ben Blanchard, Reuters, June 12, 2015]

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: In China’s wealthiest cities, most workers still commute very long distances (sometimes hours each way) on public transportation, and work very long hours for salaries generous by Chinese standards, but still just a fraction of those of global peers. But compared to the floating population, the xiagang, the villagers, or indeed their own parents, these workers by and large have opportunities undreamt of, and their future looks as boundless as that of China as a whole. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Legal status as an urban dweller in China is prized. As a result of various state policies and practices, contemporary Chinese urban society has a distinctive character, and life in Chinese cities differs in many ways from that in cities in otherwise comparable developing societies. The most consequential policies have been the household registration system, the legal barriers to migration, the fostering of the allembracing work unit, and the restriction of commerce and markets, including the housing market. In many ways, the weight of official control and supervision is felt more in the cities, whose administrators are concerned with controlling the population and do so through a dual administrative hierarchy. [Source: Library of Congress]

“The two principles on which these control structures are based are locality and occupation. Household registers are maintained by the police, whose presence is much stronger in the cities than in the countryside. Cities are subdivided into districts, wards, and finally into small units of some fifteen to thirty households, such as all those in one apartment building or on a small lane. For those employed in large organizations, the work unit either is coterminous with the residential unit or takes precedence over it; for those employed in small collective enterprises or neighborhood shops, the residential committee is their unit of registration and provides a range of services.

See Real Estate

See Separate Articles: HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com URBANIZATION AND URBAN POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUKOU (RESIDENCY CARDS) factsanddetails.com CITIES IN CHINA AND THEIR RAPID RISE factsanddetails.com ; MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MASS URBANIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF THE OLD NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Hutongs in Beijing Web Sites on Hutongs Wikipedia ;China Highlights China Highlights ; Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Chinatown Connectionchinatownconnection.com ; China Dailychinadaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese City” by Weiping Wu and Piper Gaubatz Amazon.com; “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Amazon.com; “Leisure and Power in Urban China: Everyday Life in a Chinese City” by Unn Målfrid Rolandsen Amazon.com; “Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration” by Kam Wing Chan Amazon.com; “China's Housing Middle Class: Changing Urban Life in Gated Communities” by Beibei Tang Amazon.com “The Specter of "the People": Urban Poverty in Northeast China” by Mun Young Cho Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com; Development of Chinese Urban Life “Chinese Urbanism: Urban Form and Life in the Tang-Song Dynasties” by Jing Xie Amazon.com“The Urban Life of the Yuan Dynasty” by Shi Weimin, Liao Jing, Zhou Hui Amazon.com; “The Urban Life of the Ming Dynasty” by Chen Baoliang, Zhu Yihua, et al. Amazon.com; “Urban Life in Contemporary China” by Martin King Whyte and William L. Parish (1984) Amazon.com; “China’s Urban Villagers: Changing Life in a Beijing Suburb by Norman A. Chance (1991) Amazon.com

Urban Mentality and Benefits in China

Describing how the mentality of urban areas, a newspaper editor told the Atlantic Monthly: “In the city the old village ties are left behind. Everyone lives close together. The state is part of everyone’s life. They work at jobs and buy their food and clothing at markets and in stores. There are laws, police, courts, and schools. People in the city lose their fear of outsiders, and take an interest in foreign things.”

“Life in the city depends on cooperation, in sophisticated social networks. Mutual self-interest defines public policy. You can’t get anything done without cooperating with others, so politics in the city becomes the art of compromise and partnership. The highest goal of politics becomes cooperation, community, and keeping peace. By definition, politics in the city becomes nonviolent. The backbone of urban politics isn’t blood, it’s law.”

Urban dwellers receive more benefits and socials services than rural people. Nearly all get health insurance through their companies or the government. Over 60 percent of the elderly people in the big cities receive a pension, compared to six percent in rural areas. City schools are better and have lower fees than rural schools.

Busy, Blocked Streets in 19th Century China

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “The contracted quarters in which the Chinese live compel them to do most of their work in the street. Even in those cities which are provided with but the narrowest passages, these slender avenues are perpetually choked by the presence of peripatetic vendors of every article that is sold, and by peripatetic craftsmen, who have no other shop than the street. The butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker, and hundreds of other workmen as well, have their representatives in perpetual motion, to the great impediment of travel. The wider the street, the more the uses to which it can be put, so that travel in the broad streets of Peking is often as difficult as that in the narrow alleys of Canton. An “imperial highway” in China is not one which is kept in order by the emperor, but rather one which may have to be put in order for the emperor. All such highways might rather be called low-ways; for, as they are never repaired, they soon become incomparably worse than no road at all. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “The free and easy ways of the country districts are well matched by the encroachments upon the streets of cities. The wide streets of Peking are lined with stalls and booths which have no right of existence, and which must be summarily removed if the Emperor happens to pass that way. As soon as the Emperor has passed, the booths are in their old places. The narrow passages which serve as streets in most Chinese cities are choked with every form of ' industrial obstruction. The butcher the barber, the peripatetic cook with his travelling restaurant the carpenter, the cooper, and countless other workmen,, plant themselves by the side of the tiny passage which throbs with the life of a great metropolis, and do all they can to form a strangulating clot. Even the women bring out their quilts and spread them on the road, for they have no space sa broad in their exiguous courts. There is very little which the Chinese do at all, which is not at some time done on the street. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith,1894]

“Nor are the obstructions to traffic of a movable nature only. The carpenter leaves a pile of huge logs in front of his shop, the dyer hangs up his long bolts of cloth, and the flour-dealer his strings of vermicelli across the principal thoroughfare,, for the space opposite to the shop of each, belongs not to an imaginary "public," but to the owner of the shop. The idea that this alleged ownership of the avenues, of locomotion entails any corresponding duties in the way of repair, is not one which the, Chinese mind, in its present stage of development, is capable of taking in at all. No one individual, even if he were disposed to repair a road (which would never happen) has the time or the material therewith to do it, and for many persons to combine, far this purpose, would, be totally out of the question, for each would be in deep anxiety lest he should do more of the work,, and receive less of the benefit, than some ath,?r person. It would be very easy for each local magistrate to require the villages lying along the line of the main highways or within a reasonable distance thereof, to keep the important arteries of travel passable 1 at almost all seasons, but it is doubtful whether this idea ever entered the mind of any Chinese official

Walled Cities in 19th Century China

The word for city in Chinese is the equivalent of “walled city.” Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: The laws of the Empire require that every district city, as well as every city of a higher rank, shall be enclosed by a wall of a specified height. Like other laws, this statute is much neglected in the letter, for there are many cities the walls of which are allowed to crumble into such decay, that they are no protection whatever, and we know of one district city invested by the Taiping rebels and occupied by them for many months, the walls of which although utterly destroyed were not restored at all for more than a decade afterwards. Many cities have only a feeble mud rampart, quite inadequate to keep out even the native dogs, which climb over it at will. But in all these cases, the occasion of these lapses from the ideal state of things is simply the poverty of the country. Whenever there is an alarm of trouble, the first step is to repair the walls. The execution of such repairs affords a convenient way in which to fine officials or others who have made themselves too rich in too short a time. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith,1894]

“The firm foundation on which rest all the many city walls in China, is the distrust which the Government entertains of the people. However the Emperor may be in theory the father of his people, and his subordinates called "father and mother officials," all parties understand perfectly that these are purely technical terms, ie. plus and minus, and that the real relation between the people and their rulers is that between children and a step-father. The whole history of China appears to be dotted with rebellions, most of which might apparently have been prevented by proper action on the part of the general Government if taken in time. The Government does not expect to act in time. Perhaps it does not wish to do so, or perhaps it is prevented from doing so. Meantime, the people slowly rise as the Government knew they would, and the officials promptly retire within these ready-made fortifications, like a turtle within its shell, or a hedge-hog within its ball of quills, and the disturbance is left to the slow adjustment of the troops."

“The lofty walls which enclose all premises in Chinese, as in other Oriental cities and towns, are another exemplification of the same traits of suspicion. If it is embarrassing for a foreigner to know how to speak to a Chinese of such places as London or New York, without unintentionally conveying the notion that they are " waited cities," it is not less difficult to make Chinese who may be interested in Western lands, understand how it can be that in those countries people often have about their premises no enclosures whatever. The immediate, although unwarranted inference on the part of the Chinese is that in such countries there must be no bad characters of any kind.

Even in cases of local disturbance, when there appears to the Chinese to be no safety except such as may be got by the protection of earthen walls thrown up around villages, and when the danger, being most imminent, requires instant action, it is sometimes difficult to secure sufficient unanimity to make a wall possible. In one such case near to the writer's home, a large village disagreed, and actually separated into two sections, throwing up two distinct circumvallations, one for each end of the town, to the mutual inconvenience of each, and at a great additional expense.

Yiyun Li wrote in the The New Yorker: “In Beijing, at the entrance of my family’s” gray, Soviet-style apartment complex there was a “ public telephone, a black rotary...guarded by the old women from the neighborhood association. They used to listen without hiding their disdain or curiosity while I was on the phone with friends; when I finished, they would complain about the length of the conversation before logging it in to their book and calculating the charge. In those days, I accumulated many errands before I went to use the telephone, lest my parents notice my extended absence. My allowance — which was what I could scrimp and save from my lunch money — was spent on phone calls and stamps and envelopes. Like a character in a Victorian novel, I checked our mail before my parents did and collected letters to me from friends before my parents could intercept them. [Source: Yiyun Li, The New Yorker, January 2, 2017]

In the 1940s and 50s, under Mao and the Communists, the classical city center of Beijing was smothered under monumental Stalinist structures. Hutongs (old neighborhoods) and courtyard homes were razed and replaced with "work compounds," where housing and factories were combined within walled enclaves. Many of the thousand or so temples and monasteries that filled the city were converted to other uses. The monks and priests that resided in them were kicked out.

Beijing’s walls, as high as 40 feet in some places, came down in the early 1950s to make way for a ring road. Many relics in central Beijing were moved to the outskirts of the city so the center could become the “forest of chimneys” that Mao envisioned. Factories and housing compounds were plunked down in the middle of hutongs and Soviet-style halls, stadiums, wide boulevards and swaths of four- and five-story Socialist-style apartment compounds were built.

The American urban historian Andre Tang said that “the half of Beijing destroyed in the three decades from 1950 to 1980 constituted one of the of the single greatest losses or urban architectural culture in the 20th century.” Even so, many hutongs remained. Mao-era Beijing was like an amalgamation of charming northern Chinese villages, with a few Stalinist monuments, factories and high-rises thrown in between, Farmers used to drive their sheep through the city streets at night and roosters woke people in the morning. In the winter, people huddled in quilted coats.

Urban Families in China

Urban families differ from their rural counterparts primarily in being composed largely of wage earners who look to their work units for the housing, old-age security, and opportunities for a better life that in the countryside are still the responsibility of the family. With the exception of those employed in the recently revived urban service sector (restaurants, tailoring, or repair shops) who sometimes operate family businesses, urban families do not combine family and enterprise in the manner of peasant families. Urban families usually have multiple wage earners, but children do not bring in extra income or wages as readily as in the countryside. Urban families are generally smaller than their rural counterparts, and, in a reversal of traditional patterns, it is the highest level managers and cadres who have the smallest families. Late marriages and one or two children are characteristic of urban managerial and professional groups. As in the past, elite family forms are being promoted as the model for everyone. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Three-generation families are not uncommon in cities, and a healthy grandparent is probably the ideal solution to the childcare and housework problems of most families. About as many young children are cared for by a grandparent as are enrolled in a workunit nursery or kindergarten, institutions that are far from universal. Decisions on where a newly married couple is to live often depend on the availability of housing. Couples most often establish their own household, frequently move in with the husband's parents, or, much less often, may move in with the wife's parents. Both the state and the society expect children to look after their aged parents. In addition, a retired worker from a state enterprise will have a pension and often a relatively desirable apartment as well. Under these circumstances elderly people are assets to a family. Those urban families employing unregistered maids from the countryside are most likely those without healthy grandparents.

The government provides more generous social services to urban areas than to the countryside in part because it fears urban social unrest, which can become organized, spread and gain momentum and present a real threat to the government. By contrast rural unrest tends to be fragmented, scattered and easier to contain once its gets started.

Urban Kids Out of Touch with Nature

Children in China's urban jungle have few chances to interact with nature.Liu Xinyan wrote in The Guardian: “China's rapid economic development has changed much of the country's appearance. Childhoods of climbing trees, picking dates and grapes, catching fish, shrimp and tadpoles (or cicadas and crickets), making whistles from willow twigs, and spending all day outside until you were deeply tanned are gone. What have today's children, growing up with TVs and computers, lost? [Source: Liu Xinyan for ChinaDialogue, part of the Guardian Environment Network The Guardian, January 11, 2012]

City kids in China became cave-dwellers in an urban jungle long ago. Children lose the ability to experience nature. They can talk at length about whales or cheetahs, but not describe a flower at their feet. Parents know that if their youngsters eat too much processed food, they will not have a balanced diet; yet they are less likely to know that too much processed information will also hamper children's development.

In Richard Louv's Last Child in the Woods, the phrase "nature deficit disorder" is used to describe the broken connection between children and nature. And in a rapidly modernising and urbanising China, this phenomenon is spreading quickly.

Even an ant can cause both children and adults to panic, says Wu Yue, children's nature tutor at the Lovingnature Education and Consulting Centre. The ants, worms and lizards we often caught and played with as kids have become terrifying beasts. Similarly, an experiment once found that Japanese university students preferred to play in a concrete gully, believing that two tree-lined mountain rivers nearby were dangerous. Long-term separation from the natural environment causes estrangement, fear and the loss of the ability to appreciate nature's beauty.

See Children

Life in Shanghai’s Lilongs

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Jin Qijing pretends not to notice the rat scurrying across the pipe in her room. Dinner is on the table — a sweet and fatty braised-pork dish, hongshaorou, that is a Shanghainese favorite — and the elegant 91-year-old with a sweeping, gray coiffure doesn't want to spoil the family meal. Nobody needs to remind Jin that conditions in her traditional Shanghai neighborhood, or lilong, have deteriorated since she moved here as a teenager in 1937. Back then her lilong — one of thousands in Shanghai that set modified Chinese courtyard houses on tight European-style lanes — lived up to its name: Baoxing Cun, or "treasure and prosperity village." One family lived in each house, often with a coterie of servants and rickshaw pullers. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

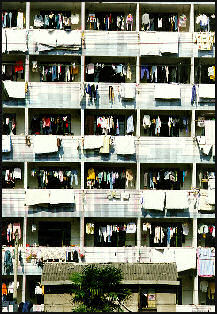

Today eight families cram into Jin's two-story home, one per room. There is no plumbing. Jin's kitchen is an electric stove erected on a rickety, makeshift balcony. Nonetheless, when Jin's grandson invited her and her husband to move into a modern apartment complex in the suburbs, she refused. "Where else," Jin asks, "could I find this sense of community?"

Baoxing Cun's densely packed alleyways still evoke the communal feeling that made lilong the cradle of Shanghainese culture. In the morning, on her way back from the open-air market, Jin passes the shop selling shengjian bao, sweet, pork-filled breakfast buns. She chats with a neighbor hanging laundry on one of the poles that festoon the lane, while a man, still in pajamas, waters his plants. "I'm back!" Jin yells, as she climbs the unlit stairs to her second-floor room. Neighbors' heads pop out of their rooms to greet her.

In the afternoon Jin and her oldest friends gather on wooden stools in the alleyway — a daily ritual they have followed for decades. With indoor space at a premium, life in the lilong spills outside, turning the lanes into public living rooms. As the women chat in Shanghainese dialect, neighbors stop by to listen, laugh, and interject: a man in an ill-fitting gray suit, a vendor walking his bicycle, an officious woman with a badge from the neighborhood-watch committee reminding Jin to show enthusiasm for Expo 2010.

Shanghai’s ‘Street of Eternal Happiness’

Rob Schmitz first came to China in 1996 as a Peace Corps volunteer assigned to Sichuan Province. In 2010, he settled in Shanghai as a correspondent for Marketplace, the American Public Media program. For his book on China, he looked no further than the street where he and his family live. “Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along a Shanghai Road” is about the people he came to know in his neighborhood in the old French Concession of Shanghai. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, May 11, 2016]

Rob Schmitz told the New York Times: I moved to the street in 2010... settling into a condominium complex covered in white bathroom tiles named the Summit — easily the least interesting place along the street. The rest of the thoroughfare was filled with life: crowds streaming in and out of the local wet market, customers lining up for steamed pork buns, grannies dancing in unison to the latest pop songs in the adjacent public square and ambulances screaming past to one of the three hospitals along the street.

“Overlooking all this chaos were lines of majestic plane trees that had been planted every 15 feet or so by the French in the 19th century, pruned to form a green tunnel that offers protection from the oppressive heat in the summer. I pedaled my bike every day inside that leafy tunnel, dodging cars, scooters and the rest of the commotion that filled the street. Over the years, I got to know several shopkeepers, most of whom hailed from throughout rural China. They’d dragged their families across the country with little more than their meager savings and a dream to make it in China’s biggest city.

“Shanghai has always attracted capitalists from near and far, and it was the first place in mainland China where foreign and Chinese ideas competed for space. A century ago, the city was divided into foreign concessions and settled by businesspeople from all over the world. Today, 40 percent of the city hails from other parts of China. Their linguistic and cultural differences remind me of turn-of-the-20th-century New York City, with its influx of immigrants.

People on Shanghai’s ‘Street of Eternal Happiness’

Rob Schmitz told the New York Times: “For better or worse, being surrounded by Shanghai’s wealth impacts the lives of all the characters in my book. Auntie Fu dumps her pension into one get-rich-quick scheme after another, dragging me along as her concerned companion to weekly meetings for a variety of pyramid investment schemes. Mayor Chen loses his home to the unchecked greed of local officials, who couldn’t keep their hands off one of the city’s most valuable plots of land. Shanghai has always been a place where fortunes rise and fall. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, May 11, 2016]

“Xi Guozhen has spent the past two decades in and out of prison for petitioning the government to investigate the death of her husband, who was burned to death when the local government cleared her neighborhood to build the high-rise I now live in. The couple’s son, on the other hand — also a victim of that land grab — is finishing his doctorate at an Ivy League university and works as a high-paid derivatives trader at one of the largest banks in Hong Kong.

“How these characters navigate the system ultimately helps determine their fates. I compare their efforts to swimming in waters with a strong rip current. If you swim against the current, you’ll likely drown. If you submit, it’ll drag you out to sea. The key is to swim with the current at an angle, carving your own path without directly challenging it or, conversely, succumbing to its power.

”Of my five main characters, C. K. undergoes the most dramatic change. He had a miserable boyhood — at just 11 years old, he attempted suicide after his parents divorced. Afterwards, he threw himself into his studies and secured a coveted managerial job at a state-owned enterprise before turning his back on the “iron rice bowl” [secure employment] to chase a dream in Shanghai. When I met him four years ago, he was a rather rakish, restless and insecure entrepreneur in his 20s, selling sandwiches at a shop on the street, and accordions over the phone — where else but Shanghai can you make a living with that odd sales combination? Now C. K.’s confident and successful, and he’s on a new quest for spirituality. He’s discovered the tools to navigate a system he spent much of his life struggling against, and he’s searching for deeper meaning. I see him as a symbol of China’s future.

Shanghai Deserves to Rank Higher in International Surveys

Harry den Hartog wrote in Sixth Tone: Shanghai is, without a doubt, one of the world’s most avant-garde cities, filled with contrasts and extremes, continuously renewing itself and expanding rapidly. “Yet despite its many advantages, Shanghai rarely appears high up on lists of the world’s most livable cities. The 2017 Mercer Quality of Living Survey, undertaken by the New York-based consultancy firm, ranks Shanghai as the world’s 102nd most livable city, while the Economist Intelligence Unit — a forecasting and advisory service linked to The Economist magazine — ranked it 81st on a list of 140 cities. [Source: Harry den Hartog,Sixth Tone, October 2, 2017. den Hartog is an independent urban designer and author of ‘Shanghai New Towns: Searching for Community and Identity in a Sprawling Metropolis']

“Many supposedly authoritative sources define livability in terms of comfort, economic vitality, cost of living, and cultural entertainment. However, the metrics they use are open to question, not least because they associate greater livability with the lifestyles of a wealthy global elite. In addition, their rankings are commonly skewed in favor of contemporary Western lifestyles and ignore how locals have traditionally resided in their chosen cities. A further issue arises when we consider how to compare such different urban areas. Airinc, a website that strongly considers air quality in determining a city’s livability, puts Shanghai at No. 73 out of 150 cities surveyed. In first place is Zürich, Switzerland; however, Zürich’s population of 400,000 practically makes it a small town compared to the tens of millions of people in Shanghai. How should we account for each city’s ability to deal with vastly different urban development issues?

“Under enormous demographic, economic, and ecological pressure, Shanghai functions remarkably well. With its advanced public transportation system, combined with shared bikes and even shared electric cars, Shanghai is setting examples of sustainable development, despite its historic problems with pollution and congestion. Shanghai retains its exciting mixture of Eastern and Western architectural styles, an often-overwhelming morass of rich and poor, chaos and order, urban and rural, high-rise and low-rise, old and new, beauty and ugliness. These contrasts were not planned; they emerged thanks to multiple influences from thousands of migrants with all kinds of backgrounds. This wide variety of influences, expressions, and emotions is what gives character and soul to this singular city.

“According to the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, six indicators define a city’s prosperity: productivity, infrastructure, quality of life, equity and social inclusion, environmental sustainability, and governance and legislation. Compared to the rather more biased metrics mentioned above, these indicators cover a broader spectrum encompassing almost all aspects of urban life. Most importantly, the UN’s criteria consider the living standards of all residents — not only those of social elites, expatriates, and the middle class. Why not use these metrics to shape our ideas of livability, too? Despite its issues, Shanghai certainly deserves a high score by any of the UN’s indicators. Admittedly, the city probably wouldn’t challenge the world’s front-runners, but it certainly wouldn’t languish in mid-table obscurity, either.

Fake Lives in Beijing?

Jiayun Feng wrote in Sup China: In July 2017, Chinese blogger and novelist Zhang Wumao published an essay titled “In Beijing, 20 million people are faking a life” on WeChat. The article went viral, generating more than 5 million views and nearly 20,000 comments overnight, triggering a heated debate and sparking a series of countering articles, including some by state media such as the People’s Daily and Xinhua. [Source: Jiayun Feng, Sup China, July 28, 2017]

“Zhang’s essay is caustically funny. He writes about the alienation of people living in a Beijing that is too big, too polluted and congested, and too expensive. At least for migrants: Zhang writes about rich old Beijingers who have “five apartments under their butts,” while the people from the provinces who do most of the work in the city struggle to afford even a tiny house in the outer suburbs. He also writes about the ongoing teardown of small shops and restaurants — mostly owned by non-locals — and how the years of destruction mean that even old Beijingers don’t really have a home to go back to. The essay ends: Those who have achieved their dreams of success are now escaping. They’re off to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or the West Coast of the United States. Those whose dreams have been dashed are also escaping. They are returning to Hebei, the Northeast, to their hometowns.

“There are over 20 million people left in this city, pretending to live. In reality, there simply is no life in this city. Here, all we have is the dreams of a minority, and the work of the masses. Online, the essay was praised by some for its authenticity and insightfulness, while others criticized it for making a fuss out of nothing. A variety of commentaries emerged on Chinese social media, including the most popular one (in Chinese), “You owe every Beijing child five houses,” a direct rebuttal to Zhang’s claim about the housing wealth of Beijingers.

“Xinhua published its own response — a commentary (in Chinese) called “Lives in a city cannot be faked,” which states, “Every city is made up of locals and immigrants,” adding, “Beijing, in fact, is every Beijinger’s home. Meanwhile, it is the capital of the whole nation.” The People’s Daily also published an article (in Chinese), blaming Zhang for “inciting sentiments” on purpose, to which one internet user replied (in Chinese), “Apparently, sentiments are not allowed in Beijing.”

Construction and Construction Noise in China

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in ”CultureShock! China”: Construction sites are a major source of noise pollution. Check if there are any near your apartment. Even a person with the steadiest nerves in the world can be reduced to blithering mush after two weeks of non-stop drilling or pounding which has left them sleepless for nights on end. Walk the exterior of the building and see if there is any construction going on nearby. It is also critical to understand if there are any unfinished apartments in the block you are looking at, and if so, when they intend to renovate them. The sound of drilling and hammering in cement buildings carries many floors each way. ”CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

“Typically the construction crew is from the countryside and lives in the apartment while they are renovating it. They get paid by the job and want to hurry through it. Regardless of building regulations, they will start tapping away as soon as the sun comes up and they are awake, and if under time pressure to finish, will do the same in the middle of the night.

“Many cities have adopted regulations for renovations to assure reasonable coexistence during it by neighbours. If there is renovation that will be going on in your building, you must feel confident that the building management will police it properly. If they are not diligent, the situation quickly deteriorates into you having to take matters into your own hands and do battle with poor peasant farmers who have no reason to listen to you. It is a no-win situation on both sides at that point. Apartments in China typically come either partially or fully furnished.

Dangers in a Chinese Cities

He Na wrote in the China Daily, “From sinkholes, to flooding caused by antiquated and underdeveloped drainage systems, to falling glass curtain walls: China's cities have become dangerous places to live, residents say. Four people were killed and nine injured by sinkholes across the country” in September last month. Nine such incidents occurred in Harbin alone over a period of 20 days. A Beijing woman died from burns to 99 percent of her body when she fell through a sidewalk into scalding water on April 8. [Source: He Na, China Daily, October 7, 2012 \=] “Outdated drainage systems have been a massive contributing factor to urban residents' woes this year, not least in Beijing, where 79 died in flooding caused by a storm on a single day in July 2012. One man was killed when his car was trapped beneath an overpass on the Second Ring Road. The road was inundated despite a giant pump running at full speed to clear the floodwater. The death toll prompted a mix of shock and anger among citizens, who demanded an explanation from authorities. Although the city's heaviest rainfall in six decades was the direct cause, many people found it hard to understand how a modern metropolis could be turned into a lake in a day. "Beijing revealed its true self after just one rainstorm," said Sun Xin, 22, a web designer for an IT company in the capital's Zhongguancun area. "If this can happen here, I can't imagine what would have happened if the storm had struck another city." \=\

Beijing's drainage system consists of 5,100 km of pipeline, roughly the equivalent to the distance between the capital and Bangkok. Nearly 1,200 km is at least 30 years old, with some of it dating back six decades. This is typical for most cities, experts say. "As well as (drainage), the surface collapse is more related to poor urban planning and management, both before and after construction," Shan Qingqing, an associate researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute for Urban and Environmental Studies, was quoted as saying by the online edition of People's Daily. \=\

“Li Xiaoxi, deputy director of Beijing Normal University's academic committee, agreed and added in the same report: "City construction not only needs to focus on the 'face' (above ground), but also the underground. Urban planning and emergency measures all need to be improved. "In the meantime," he said, "it also needs to be made clear who is responsible (in the event of an accident)."\=\

“Li Dongsheng, who moved to Beijing from Hunan province six months ago to look after his newborn grandson, sees danger everywhere. "The capital has such strong winds, so you have to pay attention to the advertising billboardings, too," the 56-year-old said. "Also, escalators," he went on, referring to a spate of fatal accidents last year. "We use the stairs now, because I worry about the escalator reversing direction." And it does not stop there. "On crosswalks, you have to watch carefully, as drivers go through red lights and may hit you," he warned. "Even at home, I now worry that our elevator may suddenly lose control, after reading reports about that happening in recent weeks". \=\

Underground Pipes and Killer Sinkholes in Harbin

He Na wrote in the China Daily, “Xu Dajiang has learned to tread lightly on his daily walk to work. He says he has reason to be cautious. In mid-August, a giant hole opened up in the middle of Liaoyang Street, a road he regularly travels in Harbin, swallowing four people. An elderly lady and an 8-year-old girl were killed on the spot. "It could happen to anybody," said the 30-year-old food-quality inspector. "Now I pay special attention when I see that a road is being repaired. My wife refused to leave the house for two weeks, fearing she would suddenly disappear into the earth. She still takes detours to avoid the places that had the cave-ins," he added. [Source: He Na, China Daily, October 7, 2012 /=/]

The collapse in August devastated Harbin, a city in Heilongjiang province famous for its exotic Russian-style buildings and winter festivals. Police say they are still investigating the fatal cave-in on Liaoyang Street. Experts and the public, however, are already pointing fingers at poor urban planning and shoddy underground construction, and many people have taken to the Internet to vent their fears and anger. "Unbelievable. People just vanished on the street," wrote a blogger on Sina Weibo, a Twitter-like website, on Sept 25. "I'll go to Harbin for a business trip tomorrow. I hope there are no cave-ins." Another posted, "Please hold your friends' hands firmly (in the street) because it's a case of 'now you see them, now you don't'." /=/

“Zhao Shuang, who lives near Liaoyang Street, told China Daily the road has frequently been dug up and repaired over the past five years, either to lay or repair cables and gas pipes. "Why can't they do all of these things at once?" he asked. "It's extremely inconvenient for us residents." In a recent essay, Lei Haiying, director of the Geological Environment Institute in Beijing, said the frequent cave-ins indicate metropolises are witnessing a surface stability crisis. In every square kilometer, a city will have an average of 25 km of utility pipelines for water, sewage, gas, cable television and telecommunications, he wrote, adding that construction and maintenance is more often than not covered by a range of agencies. /=/

“Although many cities have established early warning and emergency response systems, Lei said they are not very professional. Instead of investigating accidents after they occur and repairing the damage, at huge cost, the goal should be to eliminate the hidden danger, he added. "Various pipes of different functions are buried underground, running either parallel or intersecting each other," said Li Hongchang, an associate professor at Beijing Jiao Tong University's School of Economics and Management. "What often happens is one pipe has a problem and then affects others around it, making accidents harder to investigate and repair."”

Glass Falling from Tall Buildings in China

He Na wrote in the China Daily, “Liu Ting, who runs a fast food restaurant franchise in Shenzhen, said she is forever warning her husband to be wary when walking next to tall buildings during business trips. "These glass walls are like time bombs," said the 31-year-old, who is expecting a baby in November. "I was almost hit by glass as it crashed down from Baifu Mansion” in 2011. “I was terrified. "I bought a lottery ticket that night," she said, referring to the Chinese saying that if someone survives a tragedy they will enjoy good luck for the rest of their life. "Now, whenever I read or hear about a similar event, I get the same terrible feeling." [Source: He Na, China Daily, October 7, 2012 /=/]

“As Chinese cities have started to resemble their glitzy Western counterparts, with modern designs and skyscrapers wrapped in glass, aesthetic beauty has brought with it this hidden danger. In recent years, poorly fitted or maintained design features have damaged property and injured a number of people, including a 19-year-old woman in Hangzhou whose leg was virtually severed below the knee by a shard of glass that plummeted from the 21st floor of an office tower. Glass curtain walls began appearing in China in the 1980s. They generally have a design life of 25 years, although the bolts and adhesives only last 10 to 15 years. /=/

"Just like people need physical checkups, glass curtain walls need to be checked, maintained or replaced regularly to maximize their service life," said Yu Hui, a professor of architecture at Dalian University of Technology. "It's common sense, but no one wants to do it because of the high costs involved. "So far, we have no clear guidelines on who should be responsible for maintenance of these walls, so when accidents happen, victims often find it hard to claim compensation," he said. Lu Jinlong, an assistant chief engineer at the Shanghai Research Institute of Building Sciences, suggested authorities do more to avoid accidents, such as building or increasing green areas around buildings to act as buffer zones. Most important, he added, China's technical code for glass curtain walls, introduced in 1996, urgently needs to be updated. /=/

Image Sources: 1) Sholder pole, apartment side and Shanghai neighborhood, Louis Perrochon; 2) Yangtze town, Beifan.com 3) Shanghai suburb, New York Times ; 4) Plastic trees, Pico Poco blog; 5) Destruction of neighborhoods, Mongabay.com 7) Broadtown, Atlantic Monthly

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021