CHINA’S BUILDING BOOM

a new development,

the Xujiahui Grand Gateway in Shanghai China is in the middle of the greatest building boom in human history. Tower blocks are being built in China’s cities at a rate of four a day — almost all fitted with air conditioning, heating, lighting and elevators that will run on coal-powered electricity.

While Dubai and other cities in the Middle East are building a handful of still higher structures, nowhere can compare with China for the sheer mass of supertowers being planned or under construction. Six of the world's 10 tallest buildings completed in 2008 were in China, including the 492-meter-tall Shanghai World Financial Center. Even taller structures are on their way — such as the Shanghai Center, 632 meters, and at 600 meters, the Goldin Finance 117 in Tianjin. [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, May 27, 2009]

One management consultancy firm estimates that China will erect up to 50,000 new skyscrapers between 2010 and 2025. Along with smaller structures, McKinsey estimates that buildings will account for 25 percent of China's energy consumption by then, up from 17 percent today.

The losers have been ordinary citizens, ousted from their homes with cut-rate compensation and scant legal recourse. Powerless to stay and too poor to move, many Chinese have rebelled. Nail houses — homes sticking out on tracts of cleared land, whose owners resist eviction — are common. So are tales of corruption and other abuses. In Beijing protesters from neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city marked for demolition have marched to city and district government offices, demanding a fairer deal, and set off fireworks.

People who have gone to court to save their property have mostly lost their claims. Some who refused to move have been sent to jail

See Separate Articles: URBANIZATION AND URBAN POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUKOU (RESIDENCY CARDS) factsanddetails.com CITIES IN CHINA AND THEIR RAPID RISE factsanddetails.com ; MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MASS URBANIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Hutongs in Beijing A good book on hutong life is “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Web Sites on Hutongs Wikipedia ;China Highlights China Highlights ; Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Chinatown Connectionchinatownconnection.com ; China Dailychinadaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Amazon.com; “Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity by Qin Shao Amazon.com; The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City: by Juan Du Amazon.com; “Governing the Urban in China and India: Land Grabs, Slum Clearance, and the War on Air Pollution” by Xuefei Ren Amazon.com; Urban Life in China: “Leisure and Power in Urban China: Everyday Life in a Chinese City” by Unn Målfrid Rolandsen Amazon.com; “Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration” by Kam Wing Chan Amazon.com; “China's Housing Middle Class: Changing Urban Life in Gated Communities” by Beibei Tang Amazon.com “The Specter of "the People": Urban Poverty in Northeast China” by Mun Young Cho Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com

Urban Development and Destruction in China

Mao Zedong once said, There is no construction without destruction. Destroy first, and construction will follow. China’s property boom in the 2000s has spawned new cities, remade older ones and — not incidentally — helped float the buoyant economy that is a bedrock of Communist Party legitimacy. But its benefits are spread unevenly. [Source: New York Times, Michael Wines and Jonathan Ansfield, May 26, 2010]

In Beijing, 60 areas were demolished in 2010 mainly to erect high-rise complexes and greenbelts. More than 180,000 residents were affected and there were a number ugly clashes. Redevelopment plans elsewhere total scores of billions of dollars: a single city, Chongqing, last month unveiled plans to invest one trillion renminbi ($146.4 billion) in 323 projects.

Local governments have powerful incentives to stoke sales, for they control much of the land, and need land profits more than ever to finance new projects. In China’s 70 biggest cities, government land-sale revenues leaped 140 percent in 2009, to $158.1 billion. Land sales provide up to 60 percent of local government revenues, by one semiofficial estimate — and much more by some private ones.

A hospice administrator named Li Songtang can often be found poking around the rubble, looking for remnants pf Beijing’s past. Manchu hitching posts, ornate wooden doorways, a giant granite horse that graced an emperor’s palace and a Song Dynasty lintel pulled from a pig sty are among the thousands of objects Li has salvaged and placed in his private museum, the Songtangzhai Museum.

Problems with Urban Development in China

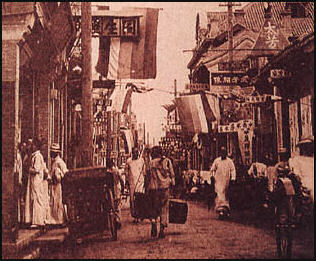

19th century Beijing

In August 2010, China heritage chief Shan Jixiang said frenetic development is wasting resources and razing valuable city center districts to make way for “superficial” skyscrapers. “Bulldozers have razed many historical blocks," he said. “The protection of cultural heritage in China has entered the most difficult, grave and critical period...Much traditional architecture that could have been passed down for generations as the most valuable memories of a city has been relentlessly torn down.[Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, August 4, 2010]

The China Daily reported that in Beijing alone, 4.43 million square meters (1,100 acres) of old courtyards had been demolished since 1990 — equivalent to around 40 percent of the downtown area. In 2009, cultural heritage officials warned that urban development had destroyed tens of thousands of historic sites in the past three decades. In 2007, the vice-minister of construction launched a similar attack on the “senseless actions” of officials who knocked down precious sites and cultural relics to produce identikit cities. His criticisms have had little, if any, effect on the drive to redevelop cities.

Shan warned that small and medium-sized cities were throwing up high-rises and skyscrapers in a bid to imitate metropolises, rendering too many cityscapes “rigid, superficial and dull”. He also said many buildings had been demolished while they were still usable, adding: “That is a disaster for both the environment and resources.” According to China Daily, the average Chinese building lasts 30 years — compared to 74 years for those in the US and 132 years for British construction.

On redevelopment in Beijing , Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: The destruction of this 800-year-old city usually proceeds as follows: the Chinese character for demolish mysteriously appears on the front of an old building, the residents wage a fruitless battle to save their homes, and quicker than you can say Celebrate the New Beijing, a wrecking crew arrives, often accompanied by the police, to pulverize the brick-and-timber structure.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 18, 2009]

Problems with the Chinese Urban Development Model

Huang Yasheng from MIT's Sloan School of Management says official statistics show living standards for average Shanghainese have only shown moderate improvement, and the property boom has translated into “almost zero gain for people on the ground in terms of property income.” He says this has happened because the state has requisitioned land from its residents at artificially low prices, and sold it off at higher, market rates, keeping the difference. [Source: Louisa Lim, National Public Radio, January 23, 2009]

“The way that China has urbanized is overbuilt, overinvested without making average people rich,” he says. “Developers get rich, government officials get rich. Essentially you have a building boom, you have property development, but because the land prices are controlled by the government, the people don't get that much from the building boom.”

The main beneficiaries of urban development have been developers and local governments. By some estimates, property has accounted for half the revenues of local governments.

On the cost of rapid development in her home city of Hefei in Anhui Province, a longtime resident told the Los Angeles Times, “Things used to be really good. Kids used to play outside, neighbors used to pop in. Now I’m scared to go outside. I used to know all the roads, but now I get lost sometimes.”

Even yuppies are suffering. Twenty-eight-year-old David Liu and his his wife Jane Chen, this pair of young well-educated professionals in Shanghai, saw property discounts lower the value of their brand new $200,000 flat in Shanghai's Pudong by about 20 percent — even before he's moved in.

Land Seizures, Development and Self-Looting

The noted economist Wu Jinglian, citing rural affairs experts, estimates that farmers whose land has been seized have lost between 20 trillion and 35 trillion renminbi, or between $3.1 trillion and $5.4 trillion, in land value since the beginning of economic reforms in 1978. He posted his findings in an article on the Web site of the Rural Development Research Institute of Hunan Province. [Source: New York Times, Didi Kirsten Tatlow , June 22, 2011]

If anything the The pace is quickening, according to a report in January by the China Construction Management and Property Law Research Center in Beijing. In 2009, local government income from land use sales was $219 billion, an increase of 43.2 percent over 2008, the center reported, using official data. In 2010, that soared to $417 billion, an increase of 70.4 percent over 2009, the report said.

China today is rich, says Zhang Musheng, a well known intellectual who has specialized in rural development. His ideas eschew pigeonholing and are, unusually, supported by members of both the political left and right, as well as some in the top leadership and military. Once, imperial nations looted other nations to amass wealth, he said.

“We looted ourselves,” Mr. Zhang said in a video interview with NetEase Books, following the publication in April by the Military Science Publishing House of his book “Changing Our View of Culture and History.” “When you loot yourself, you can take quite a bit as well, especially in a country like ours with such a large population,” Mr. Zhang said.

In the last three decades, China’s farmers have “contributed” 200,000 square kilometers, or about 77,000 square miles, of land to development, with little compensation, he said. Through these and other measures, state-owned enterprises in China now own about 100 trillion renminbi in capital, Mr. Zhang estimated.

A form of crony capitalism has emerged, he said, with special interests using government connections to create vast wealth. The result is a divided, often antagonistic society. “We’ve created a mess, and this mess needs to be cleared up,” he said.

Today, the pressure for political reform from many sectors of society is as great as the pressure for economic reform was back in 1978, he said. It won’t be easy. The Communist Party is the patient, but “it wants to operate on itself, and that’s very difficult,” said Mr. Zhang, who believes the party should continue to lead, but that it needs debate, and not just behind closed doors. “The era of “no debate” is already over,” he said, using a phrase he coined five years ago. “If we can debate this, I think we can clear up all these issues. “Today is a time of great political crisis. Don’t imagine their life is easy,” he said, referring to China’s leaders.

Destruction of Old Neighborhoods in China

In Beijing, Shanghai and elsewhere, old homes, old building and entire old tightly-knit neighborhoods have been torn down to may way for skyscrapers, offices complexes, shopping malls and other forms of modern development. Tens of thousands of urban residents have been forced to move or have been evicted. Some residents in the Qiamen district of Beijing were forced out of their houses while police officers carted away the lights and furniture. Residents there were paid about $1,000 per square meter, about a fifth of what developers plan to charge for rebuilt old-style courtyard houses.

In Tianjin, historical 600-year-old neighborhoods have been torn down to make may for office complexes financed by a Hong Kong developer. In Suzhou tea gardens and houses with beautiful courtyards have been demolished and replaced by tourist hotels. In Beijing, entire Ming dynasty neighborhoods have been torn down and replaced by Hong Kong-style high-rises.

Local authorities have the power to condemn buildings and clear land without even conducting a hearing and turn the land over to real estate developers in sweetheart deals. People have routinely been suddenly evicted from their neighborhood to make way for urban developments and given only pittance for compensation. Even those who are fairly compensated are relocated to suburbs about an hour away from their old houses and their new neighbors are mostly strangers.

In 2012, Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, Developers in Beijing have demolished the home of architects Liang Sicheng and his wife Lin Huiyin, whose appreciation of China's ancient buildings and their devotion to preserving its heritage made them two of the country's most revered architects. Liang is known as the father of modern Chinese architecture, and much of his and Lin's most important work was carried out while they were living in the courtyard house in Beizongbu Hutong in the 1930s. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 30, 2012]

The demolition took place over the lunar New Year, despite the fact it is rare for labourers to work during the festival, raising suspicions that the company hoped to avoid publicity. A Beijing official told state news agency Xinhua the firm wanted to prevent the residence being harmed during last week's holiday, apparently referring to the fireworks which are let off. Other Chinese media quoted an unidentified developer as saying that the demolition was "in preparation for maintaining the heritage site" because the buildings were in bad condition. But heritage protection activist Zeng Yizhi — who alerted city officials to the demolition — said they should have repaired the buildings. "Liang and Lin made such a great contribution to the protection of Chinese ancient buildings. If their home can be torn down, then developers can do the same thing to hundreds of other ancient houses in the country," he told China Daily. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, January 30, 2012]

He Shuzhong, founder of the Beijing Cultural Heritage centre, said the early 20th century building was the intersection between the study and preservation of cultural relics, as pioneered by the couple, and the dangers posed by rapid urban development. Experts and campaigners are also angry because they hoped they had staved off the threat to Liang and Lin's home in 2009, when the district government approved its destruction and it was partially knocked down. Following a public outcry, the state administration of cultural heritage intervened and the site was designated a permanent cultural relic, meaning official approval was required for demolition.

See Shanghai Development, Cities, Places

Hutongs of Beijing

“Hutongs” are the mazelike, old neighborhoods in Beijing made up of traditional quadrangle courtyard homes lined up along on narrow streets and alleys and often built in accordance with the principals of feng shui. In the pre-Mao-era, many residences were occupied by single extended family units and had spacious open air courtyards. But after Communists came to power the houses were divided and occupied by several families and the courtyards were filled with shanties. In many cases a house occupied by one family was occupies six or seven. The term "hutong" is derived from the Mongolian term for a passageway between yurts (tents). It refers to both the traditional winding lanes and the traditional old city neighborhoods.

Hutongs are comprised mostly of alleys with no names that often twist and turn with no apparent rhyme or reason. They are fun to get lost in but near impossible to find anything in. The houses lie mostly behind gray brick walls and are unified into neighborhoods by public toilets and entranceways that people share. Heating is often provided by smoky coal fires that occasionally asphyxiate house occupants. Public toilets and showers are sometimes hundreds of meters away from where individuals live.

During the day old men sell vegetables; children study on desks outside their homes; small time cobblers and fruit vendors go about their business; and beauty parlors and massage parlors welcome customers into old collapsing courtyard homes. In the evening many residents gather in the alleys to eat dinner or play. Even in the middle of winter friends gather to chat in the streets and street vendors make their rounds.

Many of the alleys are too narrow for cars and the commercial buildings are too small for anything larger than family-owned shops. Next to small parks or standing alone are exercise stations with bars and pendulums and hoops and things like that, where older people like to gather and hang out and occasionally do a couple of exercises. In the morning residents scamper with their chamber pots to the public toilets. Vendors arrive mid morning with their three-wheeled carts, each crying the product or service the are selling: toilet paper, coal, recycling or knife-sharpening

See Separate Article: HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com

Demolition of Beijing's Drum Tower Homes

In December 2012, AFP reported: “Large numbers of hutong homes, some of them dating back to the Qing dynasty, will be demolished around the Drum and Bell Towers — a tourist hotspot in Beijing's historic centre — to make way for a large plaza. Notices for the "destroy and evict" project are plastered throughout the quarter. Besides protecting the historic legacy of the capital, the project is also aimed at restoring and repairing old and dilapidated buildings, the notices said. [Source: AFP, December 14, 2012 ^]

“Destroying old homes in central Beijing has particular sensitivity. Critics say new development projects rob the capital of its cultural legacy. "We have been hearing this was going to happen for years, but now that the notices are up there is not much you can do but leave," said souvenir shop seller Ma Yong."When I first saw the notices I felt nothing but despair." Besides having her rented shop torn down, Ma's small home nearby, where she lives with her retired husband, will also be flattened. ^

“Residents must negotiate compensation with the newly set up "destroy and evict" office near the Bell Tower, with compensation beginning at around 40,000 yuan (US$5,800) per square meter. Between 130 and 500 homes are to be destroyed, state press reports said. "A lot of people are opposed to the campaign, 40,000 yuan per square meter is too cheap, especially with the price of housing in Beijing sky-rocketing," said the manager of a coffee shop near the Drum Tower, who gave her surname only as Wang. "People are already asking for 150,000 yuan per square meter," she said. Others said they were happy with the compensation. "We took the money," said Zhou Li, 51, who was to move out to the suburbs with his elderly parents this weekend after living most of his life near the Bell Tower. ^

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Demolition and Preservation in Shanghai

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, ‘shanghai's old neighborhoods are disappearing. In 1949 at least three-quarters of Shanghainese lived in lilong; today only a fraction do. Two lilong adjacent to Baoxing Cun have been demolished, one to make room for an elevated highway, the other for a power switching station to light up Expo 2010. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, March 2010]

Today the ladies' banter is darkened by speculation. "We keep hearing we're next in line for demolition," Jin says. For many Shanghainese, the decades of neglect and overcrowding have turned the lilong's intimacy into something more like asphyxiation. But Jin worries that the razing of Baoxing Cun will scatter her friends to distant suburbs. "Who knows how much longer we have?" she asks.

Shanghai has taken more care than most Chinese cities to preserve its historic architecture, sparing hundreds of pre-Communist-era mansions and bank buildings from the wrecking ball. Yet only a few lilong appear on the list of protected areas. Ruan Yisan, a professor of urban planning at Tongji University, is waging a campaign to save these living repositories of Shanghai culture. "The government should demolish poverty, not history," he says. "There's nothing wrong with improving people's lives, but we shouldn't throw our heritage away like a pair of old shoes."

Not long ago a government work crew swooped in to splash Baoxing Cun with a fresh coat of cream-colored paint. The Potemkin makeover does little to conceal the neighborhood's dismal condition. Nevertheless, Jin is happy to know that, at least until after Expo 2010, Baoxing Cun will not be torn down. "Here," she says, as a bare-bellied neighbor listens in, "it's all like family."

Saving Nanjing’s Super Wutong Trees

Reporting from Nanjing, Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “Tall as a 15-story building, with a mighty trunk, crooked branches and kingly canopy of leaves, the London plane tree, Platanus x acerifolia, is prized by horticulturists and city planners as a “supertree,” immune to urban grime and smog. But can it survive a development-hungry Chinese Communist Party? In Nanjing, a southeastern city of eight million people, the answer seems — for now — to be yes. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times June 4, 2011 |~|]

“In a nation where homes and farmland are routinely chewed up for the sake of high rises and factories, a grass-roots campaign by Nanjing residents this spring to save hundreds of the trees, known here as the wutong, from a subway expansion might seem like a nonstarter. But the effort, organized mostly online, has led to a surprising compromise from local government officials. It was not a shining example of democracy in action. But neither were ordinary citizens left fuming about power-drunk bureaucrats deaf to anyone below. Maybe that is because some Nanjing officials consider the Communist Party’s credo of “supervision by the people” to be more than mere words. Or maybe it is because trees, in the scheme of development, provide an easy compromise. |~|

“Giants in the arboreal world, the wutongs were introduced in China by the French in the late 1800s or early 1900s to adorn their settlement in Shanghai, Nanjing officials say. In 1928 and 1929, Nanjing planted more than 20,000 saplings along Zhongshan Avenue, a road leading to the mausoleum of the anti-imperialist leader Sun Yat-sen, revered as the father of modern China. Many more were reportedly planted after the Communists took power in 1949. The trees grew fast and provided shade during Nanjing’s scorching summers. And they became not just a symbol of Nanjing’s graceful beauty, but of its civic philosophy. China’s capital through multiple dynasties, Nanjing regards itself as a cultural haven. Its urban plan touts the city’s integration with mountains, rivers and trees. Liu Hengzhen, a former military employee, planted wutongs in the 1950s. “They keep the whole city cool,” Mr. Liu, now 80, said as he played mah-jongg at a street cafe, its roof pierced by a massive wutong branch. “The people of Nanjing grew up together with these trees,” said He Jinxue, the daily operations director for the city’s urban construction commission. “There is so much emotional attachment to them.” |~|

That did not shield them from the onslaught of development. In 1993, more than 3,000 were felled virtually overnight to make way for the Shanghai-Nanjing Expressway. Nearly 200 more were removed to build Nanjing Subway Line Two in 2006. Then, in 2011, came Subway Line Three, calling for more than 1,000 trees — mostly wutongs — to be beheaded, uprooted and plunked down elsewhere to make space for six above-ground stations in the city center. Nanjing’s two existing subway lines, each carrying a million commuters a day, are not nearly enough, said Mr. He, the urban commission director. More than 10 new lines are planned, he said.

Grassroots Campaign to Save Nanjing’s Super Wutong Treea

Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “Once workers had reduced a first batch of 49 wutongs to trunks and a few feet of branches, the Chinese equivalents of Twitter rustled with more than 10,000 outraged messages. A schoolteacher organized students to tie green ribbons around some untouched trees. Several celebrities weighed in, including Huang Jianxiang, a freelance television host and sports commentator whose Sina Weibo microblog is followed by more than five million people. So did a Taiwan legislator with the Kuomintang Party, which made Nanjing its headquarters until it was vanquished by the Communists in 1949. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times June 4, 2011 |~|]

“Zhu Fulin, an enterprising reporter for the government-owned Nanjing Morning Post, traced the fate of 190 trees that had been moved elsewhere five years ago to construct Line Two. Despite the government’s pledge to protect and replant them, he found 80 of the wutongs languishing in a trash-strewn city field. A tree expert said 20, at most, had survived. Weeks later, even those were being knocked down to make way for an expressway. Farmers drove off with truckloads of wood, saying it would make good tables. |~| “Some critics were openly reluctant to press the government too hard. A local environmental group, Green Stone, posted tree photos on the Internet. “We didn’t want to oppose what the government was doing,” Cui Yuanyuan, a staff member, said. “We just wanted to have a channel to communicate.” Other activists said the group was vulnerable because it was small and weak, and not registered as a nongovernment organization with the Chinese authorities. Mr. Huang, the television celebrity, decided not to repost online calls for a street protest, fearful they would backfire. Yet hundreds gathered outside the city library on March 19 anyway, activists said, and the police dispersed the crowd within an hour. Censors ensured that the local news media ignored them. |~|

Deal to Save Nanjing’s Super Wutong Treea

Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “A chastened Nanjing government was already looking to compromise. Several days earlier, it had suspended the subway construction plan and announced the formation of a “green assessment committee” to review it. The eight citizen members were outnumbered by nine experts — most from government bureaus or construction companies — and eight delegates to China’s handpicked legislative bodies. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times June 4, 2011 |~|]

“A civics lesson it was not. The panel’s work took less than two days: one to tour subway station sites, and another to approve a predigested revision of the original plan. At the end of the second day, citizen members were summoned from the deliberations to receive envelopes of cash — compensation, it was said, for their transportation costs. And when it came time to vote, the group’s leader simply directed panel members to applaud if they had no objection. “There was a two-second pause, and then clapping,” said one panelist, who asked not to be named because citizens were ordered not to talk to reporters. “There was no time for consideration. There was not a democratic decision.” Nonetheless, she said, “I would still like to think of this as a step in the right direction.” Mr. Huang agreed. “In China, this process is not easy, so we have to take small baby steps.” |~|

“Under the new plan, Line Three will claim 318 trees, mostly wutongs, but it will spare more than two-thirds of trees that were to be moved. The city promised to give each uprooted tree a number and track its health wherever it is replanted. And henceforth, Mr. He said, every construction plan that affects ordinary citizens will first be reviewed by a green assessment commission. Moreover, the government will get citizens involved before, not after, it digs up trees, he said. All in hopes of preserving a separate, arboreal peace.” |~|

Image Sources: Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com Wiki commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015