HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA

Land confiscation is one of the most contentious political issues in China and accounts for many of the mass demonstrations that occur with regularity across the country. In 2012 Amnesty International estimated that confiscations have occurred in 43 percent of Chinese villages in 15 years. John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “After tax reforms cut into revenue across the country in the 1990s, local governments began exercising their right to rezone and sell land for real estate development. Chinese reports have said that the proceeds from recorded land sales, which go directly to the governments, far exceed the compensation offered to evicted inhabitants.

Rural Chinese, who receive plots of land allocated by local governments, have no individual land rights and cannot dispute rezoning plans drawn up by officials. But when officials do not offer sufficient compensation to households to relocate, the residents sometimes refuse to leave. Developers then evict the holdouts by force. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2012 |]

Land confiscation is one of the most contentious political issues in China and accounts for many of the mass demonstrations that occur with regularity across the country. In 2012 Amnesty International estimated that confiscations have occurred in 43 percent of Chinese villages in 15 years. John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “After tax reforms cut into revenue across the country in the 1990s, local governments began exercising their right to rezone and sell land for real estate development. Chinese reports have said that the proceeds from recorded land sales, which go directly to the governments, far exceed the compensation offered to evicted inhabitants.

Rural Chinese, who receive plots of land allocated by local governments, have no individual land rights and cannot dispute rezoning plans drawn up by officials. But when officials do not offer sufficient compensation to households to relocate, the residents sometimes refuse to leave. Developers then evict the holdouts by force. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2012 |]

The central government has spoken out against forced evictions, but those directives are often ignored at the local level. In 2010 Japan enacted a regulation making it more difficult for developers to demolish housing and force out landholders. A government spokesman said that "the legal rights of owners whose homes are seized are protected according to the law." Amnesty' International says that regulation covers only urban land, leaving out those living in suburbs and rural areas who make up the vast majority of people affected by forced evictions. The government technically owns most land in China and can seize property for projects deemed in the public interest. Compensation is supposed to be given to residents who are evicted, but that does not always happen or is not always fair. [Source: Louise Watt, Associated Press, October 11, 2012 /*/]

“Amnesty said one problem is that the ruling Communist Party continues to promote local officials who deliver economic growth, however it is achieved, and land redevelopment — for roads, factories or housing — is seen as the most direct path to visible results. "The Chinese authorities must immediately halt all forced evictions. There needs to be an end to the political incentives, tax gains and career advancements that encourage local officials to continue with such illegal practices," said Nicola Duckworth, Amnesty senior director of research.” /*/

See Separate Articles: HUTONGS: THEIR HISTORY, DAILY LIFE, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMOLITION factsanddetails.com URBANIZATION AND URBAN POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUKOU (RESIDENCY CARDS) factsanddetails.com CITIES IN CHINA AND THEIR RAPID RISE factsanddetails.com ; MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MASS URBANIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF THE OLD NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Hutongs in Beijing A good book on hutong life is “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Web Sites on Hutongs Wikipedia ;China Highlights China Highlights ; Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Chinatown Connectionchinatownconnection.com ; China Dailychinadaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Amazon.com; “Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity by Qin Shao Amazon.com; The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City: by Juan Du Amazon.com; “Governing the Urban in China and India: Land Grabs, Slum Clearance, and the War on Air Pollution” by Xuefei Ren Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com

Forced Demolitions in China

According to figures from the China Academy if Social Sciences fights over land account for 65 percent of rural “mass conflicts” and is also a serious problem in cities, In January 2010, a 38-year-old woman was killed by a digger while protesting against a canal project in central Henan Province in front of numerous similar and security guards. In December 2010, a village chief who had protested for years against government-backed land grabs was mysteriously run over by a truck in eastern Zhejiang Province.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “The struggle over demolition and development is a kind of national psychodrama in China, infused with emotional debate over power, progress, and fairness and fed by the competition between individual rights and collective benefits. The demolition — near the site of the Future Science and Technology City — looked nearly complete. Hundreds of houses in every direction had been turned into mounds of brick and cement and rebar. Among the rubble, a few buildings remained — the holdouts. In cases like this, there are always people who stay as long as possible, in the hope that developers will pay them extra to relocate. It's demolition roulette: in some cases, the holdouts prevail and get more money; in others, they end up being violently evicted. I reached the center of the demolition zone, where the loudspeaker was playing a recorded message in a loop, urging people to accept the compensation on offer and leave peacefully: "Don't listen to rumors! The policies on demolition and relocation will never change!" The sound echoed off the homes of the holdouts. "Sign now, and enjoy a comfortable and wonderful new life with your fellow-villagers!" [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, January 10, 2011]

People who fought authorities over their evictions have ended up in jail. Lawyers who have represented have been threatened by government officials. To protest the destruction of hutongs in Beijing some residents have chosen to kill themselves rather than be relocated. There have been a few cases of self immolations. In Shenzhen, residents successfully organized to fight the construction of an expressway through a middle class neighborhood. Taking their campaign to city hall they managed over a two year period to have work halted on the most destructive parts of the highway and forced design changes that reduced pollution. Architects and conservationist lament the loss for aesthetic reasons. Efforts by conservationists to preserve the old neighborhoods have largely been undermined by Communist party officials who believed to be receiving bribes from developers. Developers and government officials say that the inconvenience for a few is justified by developments that will help many.

Intimidation, Violence and Threats Used in Home Evictions in China

Urban residents that refuse to accept the compensation are evicted or bullied to leave. The developers often hire relocation companies to do their dirty work and they in turn use thugs to intimate the residents, in some cases, beating them up if they don’t take the compensation offer and even setting fire or bulldozing down their houses. One Shanghai resident told the Los Angeles Times he was awakened in the middle of the night with a knock at his door. Before he could answer a demolition crew had kicked down the door and began throwing their furniture out in the street and breaking down the walls with sledgehammers. When the resident tried to stop them he got kicked in the stomach.

In some cases people with dwellings on choice pieces of land have been summoned to police stations only to find their homes have been demolished when they return home. One man who was evicted right after his mother died told the Los Angeles Times, "I went out for a few minutes one morning, and when I came back, migrant workers were throwing my furniture in a truck and demolishing the house. My brother, who was sick, was sleeping when they rushed in, and they just rolled him up in his sleeping mat and threw him in the truck like furniture." This kind of intimidation is illegal but victims often have little recourse. They usually can't afford lawyers or don't have the means to negotiate the Kafkaesque Chinese legal system.

John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “These forced evictions can provoke desperate responses. Some villagers have set themselves on fire, according to Chinese media reports. Spectacular cases of armed resistance have also attracted attention, as when a farmer named Yang Youde used a homemade rocket launcher to drive away assailants from his house near Wuhan in 2010. Chinese prosecutors often bring serious criminal charges against individuals who fight back. In a similar case in north China in 2009, a man named Zhang Jian was charged with murder after he stabbed and fatally wounded a man beating his wife during a forced eviction. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2012]

Louise Watt of Associated Press wrote: “Of 40 forced evictions that Amnesty said it examined in detail” in a 2012 reported,” nine culminated in the deaths of people protesting or resisting eviction. In one case, a 70-year-old woman was buried alive by an excavator as she tried to stop workers demolishing her house in Wuhan city in central Hubei province, the report said. In another case, police in Wenchang town in southern Sichuan province were reported to have taken custody of a baby and refused to return him until his mother signed an eviction order. Wenchang police told The Associated Press that the report was untrue and that the woman had abandoned her child at the police station. "The kid was taken away by its grandmother the next day," said a man surnamed He at Wenchang's police station. "Now everything has been settled and the family received subsidies from the government." [Source: Louise Watt, Associated Press, October 11, 2012 /*/]

“Some people who resist forced evictions end up in prison or in labor camps. Amnesty said a woman in Hexia township in southeastern Jiangxi province who petitioned authorities about her eviction was beaten and forced to undergo sterilization. Hexia's authority confirmed the sterilization but said it was because the woman had three children against the country's one-child policy. "The woman first refused to be sterilized, but reluctantly agreed after our strong persuasion. If she didn't agree at all, it would be impossible for her to have surgery," said a woman surnamed Xiao. Some despairing residents have set themselves on fire. Amnesty said it documented 41 cases of self-immolations that occurred between January 2009 and January 2012. /*/

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and his take on urban demolition

Kung Ku Masters Fight Off Thugs Trying to Evict Them

John Hannon wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The men who barged through Shen Jianzhong's door probably thought it was a routine assignment: Break in and beat Shen's family into submission. Forced evictions to make way for real estate development are an everyday occurrence in China, and the family may have seemed no different from any in that situation. It was only after they forced open the door, threw Shen's wife to the ground and began to beat her that they learned the 38-year-old Shen and his 18-year-old son are kung fu masters. [Source: John Hannon, Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2012 |]

“Shen says he does not recall exactly what happened during the fight, but an eight-minute video of the aftermath shows seven of the hired hands piled in a motionless heap in Shen's doorway. Blood pools around the cheek of one; another lies halfway through the doorway, crumpled on the curb. Survivors mill about unsteadily on the street, glaring at the camera. The video, shot by Shen's wife, has attracted nearly a million views and many admiring comments since it was posted online” in October 2012. “It has turned Shen into a minor folk hero in China, where many villagers have been forced out of their homes by da shou ("beating hands" in Chinese) who work for real estate developers. |

“Shen and his family live in Bazhou, a city in Hebei province 60 miles from central Beijing. Shen says he has trained in Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do style of kung fu for 20 years. He has also been certified by the Hong Kong-based World Record Assn. for completing the highest number of roller push-ups in a minute. The exercise, which involves folding and unfolding at the waist like an inchworm while propped up with a small wheel, is more than a pastime for Shen. He and his wife run a small business teaching the exercise at home and around Bazhou, and they fear that the loss of their house would damage their livelihood. |

“Shen says he was teaching at a nearby gym on Oct. 29 when a group of more than 30 men assembled outside his house, which a local Communist Party official was planning to redevelop into an apartment complex. The men threatened and verbally abused Shen's wife as she returned home with groceries. Once Shen arrived and confirmed to the leader of the group that his family would not leave before receiving guarantees for housing, the assailants, he said, burst through the front door and began to beat his wife. In response, Shen and his teenage son, a graduate of traditional martial arts schools, entered the fray. |

“Many who have seen the video, which has not been blocked by Internet censors, applauded Shen's victory. But the incident has also prompted a number of mournful remarks about social conditions in China. "So do all Chinese people have to go to the Shaolin Temple [a historic martial arts academy] and study kung fu to do something about forced evictions?" wondered one recent blogger.” Shen said his troubles increased after the attack. “The next day, he said, nearly 100 men arrived in buses from out of town and surrounded his house. When the police refused to drive off the men on grounds that they were behaving peacefully, Shen fled with his wife to Beijing, hoping that media attention and the central government would help his family. Shen said that in his absence his house has not been demolished, but that shortly after his departure for Beijing, the Bazhou police arrested his son.” Shen returned to Bazhou a month after the altercation “to negotiate his son's fate with the police and the developer.” He said at the time his son was still in detention, and unless he came to an agreement with the developer he was afraid criminal charges would follow. “So while Shen is hopeful that the compensation for his property will increase, he also knows where the hard-won money is bound to go: He's had to retain a lawyer for his son.” |

Nail House and the Family That Refused to Budge

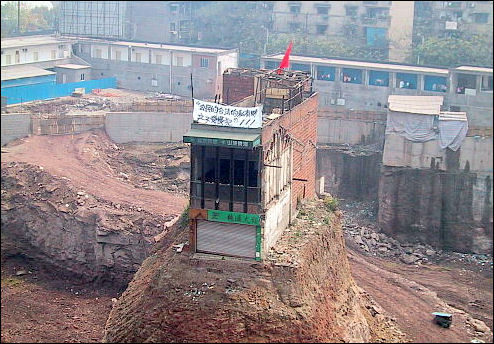

Dingzihu is the Chinese term for residents that refuse to move during demolition. The term means "nail house" – a reference to how they stick out. Nail houses are becoming an increasingly common sight during the country's rapid urbanisation. All land in China is state-owned, and residents are typically offered a fraction of their home's original value in compensation.

There have been cases where hold outs have refused compensation deals offered them and have continued living in houses surrounded by empty land after the other houses had been demolished and cleared away. The most famous of these is the “nail house” in Chongqing — a ramshackle house that sits alone on a 10-meter-high mound of earth in the middle a huge area that has been cleared away for a development. Pictures of this house have been plastered all over the Internet and the house has become a rallying point for those fighting to protect private property rights. The house was owned by a martial arts expert and his wife, who sometimes referred to herself as a Peking Opera character.

In Shengzhou in Zhejiang Province, 18 people representing four generations from a single family refused to budge from a four-story apartment earmarked for demolition to make way for road building project. They held out from 2004 to 2007, raising a Chinese flag on their roof with a sign that read “Infringement of private property not allowed.” The family complained they were only offered a third of what the property was worth as compensation.

Nail House in Chongqing

In an effort to gain possession of the building authorities turned off their water and detained several family members. When accusations of human rights abuses began appearing on Internet chat lines authorities tried to shut the chat lines down. This enraged supporters of the family all the more. A support rally, publicized by cell phones messages, was staged near the apartment. It drew 20,000 to 30,000 participants according to some sources and deteriorated into a riot in which police cars were overturned and 20 people were injured. After the last family member holdout was abducted by authorities the building was torn down.

Nail House owners Wu Ping and her husband Yang Wu held out for three years until they finally settled for higher compensation. After they left their house disappeared in just three hours.

Demolition of China’s Highway House

In November 2012, China’s 'highway house'—a house completely surrounded by a road—was demolished after its owners accepted a compensation and agreed to move. Jonathan Kaiman wrote in The Guardian: “An elderly couple have allowed their house in Wenling, Zhejiang province to be demolished, after initially refusing. A Chinese house that became an internet sensation after being left in the middle of new highway because its elderly owners refused to move out has been demolished. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, The Guardian, December 1, 2012 ]

“Photographs of the house went viral on China's social media websites last month after 67 year-old duck farmer Luo Baogen and his wife refused to sign an agreement allowing it to be demolished. This resulted in authorities building a planned road around the building. As the images spread around the world, the five-storey building became a symbol of protest against forced property demolitions, one of China's most pressing social issues.

“Luo voluntarily agreed to leave his home for 260,000 yuan (about $40,000) in compensation, said Chen Xuecai, the chief of Xiayangzhang village, Wenling city, in the coastal Zhejiang province. "Luo Baogen received dozens of people from the media every day and his house stands in the centre of the road. So he decided to demolish the house," Chen added. Luo had declined the compensation package but changed his mind after meeting local officials. "Alright, I'm willing to move," the China News Network quoted Luo as saying. Pictures on Chinese news websites show the home being torn down” a few hours after Luo agreed to the compensation.

People Set Themselves on Fire to Protest Urban Development in China

In November 2009, Tang Fuzhen, a garment factory owner, doused herself with gasoline and set herself on fire on the roof her home in Chengdu, Sichuan Province while a demolition crew looked on did nothing except beat up her family. She died of her burns two weeks later. Cell phones videos taken of her in flames on her house were widely circulated in the Internet.

Tang’s death was not in vein. Afterward the government issued new rules requiring developers to pay market-value compensation to evicted residents, and banned heavy-handed demotion crews from cutting off water or power and threatening people with violence. Before developers only needed a relocation permit to demolish properties. Critics say that despite all this it is still easy to skirt the rules and the authorities that are supposed to enforce the rules are often the same ones receiving pay-off from the developers before they make their grabs.

In September 2010, three people in Fuzhou, eastern China, were rushed to hospital in serious condition after setting fire to themselves in protest at what they said was inadequate compensation.

In November 2011 AP reported that Chinese media were reporting that an 81-year-old woman set herself on fire as officials tried to demolish her home. Financial magazine Caijing said that Wang Liushi self-immolated and died on November 3 in her family's house in central Henan province. [Source: AP, November 16, 2011]

the Caijing report said local officials said the house had been illegally constructed. Caijing quoted the family's lawyer as saying that the house was built more than 10 years ago. The Southern Metropolis newspaper says Wang's son and daughter-in-law climbed onto their roof and poured gasoline over themselves in a bid to stop the demolition team. They then heard a noise and saw smoke coming out of Wang's room.

Compensation for People Displaced form Their Homes in China

Howard French wrote in the New York Times, ‘some people are pleased with the take-it-or-leave-it buyout arrangements the government has offered to pave the way for the construction of high-rises; others respond with fatalism. If the country needs this land, what can I do? said one elderly man.” [Source: Howard W. French, New York Times, August 28, 2009]

A 75-year-old owner of a tiny barbershop whose neighborhood in Shanghai came down during a summer told Howard French of the New York Times. “What they are doing here is simply unfair, he said, telling me how thugs had been dispatched to beat up residents who refused to quietly make way for the demolition. There is no rule of law. The “lao bai xing” have no rights at all. That old phrase, meaning the nameless masses, never seemed more appropriate.” [Source: Howard W. French, New York Times, August 28, 2009]

French said others told him stories of corrupt local officials, whom they said offered higher compensation for relocated people who were willing to pay bribes. These anecdotes took on special potency in a summer where a nearly completed apartment building fell on its side, killing a worker and setting off lurid rumors of government corruption. [Source: Howard W. French, New York Times, August 28, 2009]

Legal Efforts to Curb Land Seizures in China

Increasingly top officials are worried about threats to social stability caused by the urban property rush, and the enrichment of local governments and well-connected developers at the expense of ordinary people. In 2008, China’s appointed legislature, the National People’s Congress, approved a law to strengthen individual property rights and ordered new rules written to regulate urban land. But that effort stagnated in the legislative affairs office of the State Council, China’s cabinet.[Source: New York Times, Michael Wines and Jonathan Ansfield, May 26, 2010]

Loophole-ridden land rules, dating from 2001, gave developers wide leeway to clear property. Under these rules, local governments picked renewal sites at will, left negotiations with residents to developers, demolition companies and low-level demolition and relocation offices. They frequently low-balled home-purchase offers, cut off utilities and even hired gangs of thugs to terrorize homeowners.

In May 2010, China’s cabinet issued an emergency notice to protect citizens from unchecked development by demanding that local governments hold officials accountable for vicious incidents and publicize reasonable standards of compensation. The impetus for the changes was the death of Tang Fuzhen, a middle-aged woman who doused herself in gasoline and set herself on fire on the roof of her house in November 2009 to protest the demolition of her property.

A few weeks after Tang’s death a group of Peking University law professors dispatched a plea to the National People’s Congress to overhaul the land rules. The state press took note, and days later, State Council bureaucrats not only resurrected the long-stalled plans to write new land rules, but also invited the professors and others to weigh in at closed-door meetings.

As word of the proposal spread nationwide, more than 13,000 people flooded a State Council Web site with comments on the draft. In one professor’s office in Beijing, petitions from people around the country were piled from the floor to his desktop. Among the complainants were Angry parents in Fuzhou, a southeastern city where officials were seizing a new primary school to make way for a new central business district.

The resulting draft requires developers and officials to consult homeowners, pay market rates for homes and put off demolition until sales and relocation details are settled — and, sometimes, approved by two-thirds of homeowners. It also would prohibit governments from forcibly seizing homes, in a process akin to condemnation in the United States, without specific public interest purposes. But serious loopholes remain. The draft covers only urban property, leaving out rural city outskirts where local governments have reaped huge profits — up to 100 times the value of a home — by converting commercially zoned countryside to city land.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

can you find him

New Rules on Forced Demolitions in China

In January 2011, China 's state council said it had approved a draft plan to curb forced demolitions. It stressed that developers should not be involved in land seizure projects and residents should receive fair compensation for their destroyed businesses and homes. Under the rules, according to AFP and Xinhua, violence or coercion must not be used to force homeowners to leave. If government authorities cannot reach an agreement with residents over expropriations or compensation for their property, demolitions can only be carried out after the local court has reviewed and approved them. The previous rules had authorized local governments to enforce demolitions at their own will, the report said, quoting unnamed officials at the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.

In September 2011, local governments in China were told by the Supreme People's Court — China’s top court — they should be careful with demolition projects and stop them if the residents involved threaten suicide.The move follows a rash of suicides and incidents of social unrest in the last year over enforced demolitions, including several cases of people setting themselves on fire to protest the seizure of their homes for new development. The Supreme People's Court said in a statement: "Force must be applied with caution and absolute certainty that there will not be unexpected outcome." It said that when people behave in "extreme ways" and injuries or death could be caused, then the demolition "should, in normal circumstances, be called off immediately." [Source: AP, September 10, 2011]

The response of some powerful developers to new rules was to demolish neighborhood as quickly as possible before the rules were passed or stronger rules wore imposed. Michael Wines and Jonathan Ansfield wrote in the New York Times: As a result in some places neighbors were destroyed at a record pace. Some scholars say central government officials appear torn between addressing a threat to stability and reining in an engine of economic growth. Regulators also could be preoccupied with other measures to curb property prices, they said, and waiting for prices to stabilize before issuing new rules.” For their part, local officials seem less concerned about reining in abuses than about mollifying those they evict. In Hangzhou, the Chinese city that made the most money from land sales in 2009, officials were very worried about being condemned by citizens but added that even new regulations would allow them to designate land for redevelopment under a vague public interest clause. They basically said that what needed to be demolished would still be demolished. The main issue for them was how to carry out equitable compensation. Still, the prospects of reform have energized people on the brink of eviction, and pressured at least some local governments into making changes. Cities like Hangzhou are introducing a policy of homes waiting for people, so that officials and developers can immediately resettle the displaced in affordable housing, regardless of outstanding disputes. [Source: New York Times, Michael Wines and Jonathan Ansfield, May 26, 2010]

Chinese Supreme Court Sides with Victims of Illegal Demolitions

In January, 2018, China’s supreme court ruled that local governments who seize people’s land and demolish their houses before coming to an agreement are liable for the damages. The verdict signaled a shift in how demolition cases would be handled. Fan Liya wrote in Sixth Tone, “The third circuit court of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) ruled that a district government in eastern China’s Zhejiang province owed damages to a resident for demolishing his properties without prior agreement on compensation. The verdict, made public on Tuesday, overturned previous rulings saying the resident was only entitled to his due compensation for land acquisition, even though the demolition had been deemed illegal. [Source: Fan Liya, Sixth Tone, February 1, 2018]

“According to national regulations, governments must settle compensation issues before asking residents to relocate. It is illegal to evict residents through force — yet in most such cases, governments still only pay compensation for the value of the real estate itself. With the SPC ruling, the district will now also have to pay damages for loss of business and personal items destroyed in the illegal demolition. Claimant Xu Shuiyun, 63, is a resident of Wucheng District in Jinhua, a city in Zhejiang. In September 2014, his two houses were bulldozed as part of a district government redevelopment project. A government notice about the project in August had included Xu’s properties, but the district government did not officially announce the land acquisition decision until October.

“Xu had not reached any agreement with the government regarding compensation or relocation before his houses were torn down. In December 2016, the Jinhua Intermediate People’s Court ruled that the district government had violated the law, but ordered it only to compensate Xu according to the government’s standards for compulsory land acquisitions, set in its October 2014 notice. Dissatisfied, Xu appealed to the Zhejiang High People’s Court, which in May 2017 upheld the original verdict. Xu appealed again and won last week.

“According to court records from the May 2017 trial, Xu requested 60,000 yuan ($9,500) for loss of personal items; 20,000 yuan per month from the date of demolition to the date of payment for business losses; and compensation for his houses reflecting their market value at the time of the trial rather than the date of the illegal demolition. The compensation standards that had been set out in the government’s October 2014 announcement said residents would receive between 5,149 and 11, 417 yuan per square meter, depending on the property location. “The court’s stance on this case is very clear: The government should pay the damages instead of going the old way [with just] compensation, ” Geng Baojian, the judge at the SPC’s third circuit court who handled the case, told state broadcaster China Central Television on Tuesday. “This case gives a strong signal that [the government] should strictly follow legal procedure, ” said Geng. “If you violate the law, you should bear the consequences.” Though the Jan. 25 verdict did not set an amount, it ordered the district government to negotiate with Xu on paying him administrative compensation — the class of damages that government bodies pay for abusing their power or infringing upon citizens’ rights.

Beijing Launches Another Demolition Drive, This Time in the Suburbs

Steven Lee Myers and Keith Bradsher wrote in New York Times: “The people who would destroy the village came in the middle of the night. Hundreds of guards breached the wall surrounding the village and began banging on the doors of the 140 courtyard homes there, waking residents and handing them notices to get out. Many tried to protest but were subdued by the guards, and by this week, the demolition was already in full swing. Backhoes moved house by house, laying waste to a community called Xitai that was built in a plush green valley on the northern edge of Beijing, only a short walk from the Great Wall of China. “This was a sneak attack to move when we were unprepared, ” said Sheng Hong, one of the residents.[Source: Steven Lee Myers and Keith Bradsher, New York Times, August 7, 2020]

“The destruction of the village, one of several unfolding on the suburban edges of Beijing this summer, reflects the corruption at the murky intersection of politics and the economy in China. What is perfectly acceptable one year can suddenly be deemed illegal the next, leaving communities and families vulnerable to the vagaries of policy under the country’s leader, Xi Jinping. Back when these developments were built, turbocharging China’s economy was priority No. 1 and many were blessed by local governments. Now, led by Beijing’s paramount leader, Cai Qi, the local authorities have declared that the projects in fact violated laws intended to protect the environment and agricultural land.

“This summer of demolitions follows previous campaigns to “beautify” Beijing’s historic alleyway neighborhoods, known as hutongs, and to clear away ramshackle migrant neighborhoods in the city’s south, ostensibly out of concern for building safety. Those projects largely targeted poorer residents, with a thinly veiled goal of capping the city’s population at 22 million people. The latest campaign has landed on the comparatively well-to-do, people able to afford single-family homes — in some cases second homes — in the still-largely bucolic countryside outside Beijing’s congested urban core.

“A common denominator of all these campaigns is that the people most affected have virtually no recourse once the government determines a policy, typically with no public deliberation or even much explanation. “There is no hope under this system, ” said Paul Wu, who leased a home in Wayaocun, another village about 30 miles west of Xitai. Demolitions began there in late June, targeting six different developments now declared a blight on the countryside.

Image Sources: Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com Wiki commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021