TOWNS AND CITIES IN CHINA

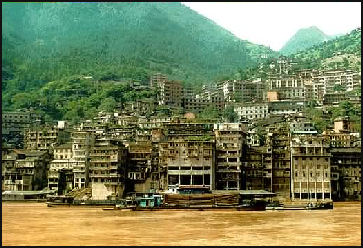

Yangtze town In China, an urban area of half-a-million people is sometimes referred to as a ‘village’. Medium-size Chinese towns are often larger than all but the largest U.S. or European cities. In China, to be considered a big city, it has to have a population of at least 5 million people. China has 19 cities with a population over 5 million, compared to two in the U.S..

Most major towns and villages are located on harbors, rivers, major roads or transportation hubs. Towns have traditionally sprung up where different agriculture districts met and markets sprung up to allow people to trade goods. Over time the market became large enough to support a permanent population of merchants and craftsmen.

The look of small towns and villages reflects the peculiarities of the environment, building skills and technology, and available materials. Forms and shapes are determined by traditions and necessity rather than a sense of taste or aesthetics. The architect Norman F. Carver Jr. wrote: villages and towns do “not aim for an artificial impressiveness or follow an alien pattern of pretentious buildings and monumental spaces. Their impressiveness lay in the rhythmic repetition of a single house type, compact and dense, arranged to reflect the social realities of small town life."

Chinese addresses are sometimes hard to figure out. Chinese often identify places by nearness to a landmark rather than a street number. Cities and towns in China traditionally have had a south-facing rectangle wall surrounding a grid of public buildings and courtyard houses with similar symmetrical layouts. Many modern towns are centered around a government compound with an ugly modernist sculpture out front, accompanied by Communist slogans that are supposed to generate and image of modernity.

Many Shanghaiers and other residents of coastal cities were relocated to remote interior cities in the early 1960s. This was part of Mao Zedong's "third front" policy of establishing safely remote bases in China's interior for strategic industries under what was perceived to be the threat of Soviet invasion. These displaced urban communities contained many members who retained a strong sense of their previous urban identities while living in this sort of internal industrial "exile". Lazhou — a city once regarded as the gateway to the Silk Road — is now one of China’s dirtiest cities. It was described in a New Yorker article as “an assemblage pf rusting machinery, slag heaps, and landfills; of chimneys, brick kilns, and belching thick smoke; of concrete tenements whose broken windows are held together with cellophane and old newspapers.”

See Separate Articles: URBANIZATION AND URBAN POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUKOU (RESIDENCY CARDS) factsanddetails.com MEGACITIES, METROPOLIS CLUSTERS, MODEL GREEN CITIES AND GHOST CITIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MASS URBANIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF THE OLD NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Hutongs in Beijing Web Sites on Hutongs Wikipedia ;China Highlights China Highlights ; Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Chinatown Connectionchinatownconnection.com ; China Dailychinadaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese City” by Weiping Wu and Piper Gaubatz Amazon.com; “Reinventing the Chinese City” by Richard Hu Amazon.com; Urban Life in China: “Leisure and Power in Urban China: Everyday Life in a Chinese City” by Unn Målfrid Rolandsen Amazon.com; “Last Days of Old Beijing: Life on the Vanished Backstreets of a City Transformed” by Micheal Meyer (Walker and Co., 2008). Amazon.com; “Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration” by Kam Wing Chan Amazon.com; “China's Housing Middle Class: Changing Urban Life in Gated Communities” by Beibei Tang Amazon.com “The Specter of "the People": Urban Poverty in Northeast China” by Mun Young Cho Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com

Chinese Cities

Shanghai suburb

A typical city was established where livestock from the dry plains was traded with grain grown on irrigated plains and produce and fruit was grown on coastal areas and in mountains. As it the matured the city became surrounded by agricultural districts that produced large surpluses that could support a large population of craftsmen and merchants.

Most Chinese cities are ugly, and people complain they all look alike and have very little to offer. Many are dominated by blocky cement buildings, crumbling apartments, dilapidated factories and pollution-belching smokestacks. Exposed power lines are piled on top of one another. The air is chocked with dust and dirt from construction projects.

China has a makeshift impermanence to it. Zoning rules and centralized planning seems non-existent. There are few parks, and typically they have few trees and look filthy and run down. Sidewalks start and stop, stairways are steep, buildings are often thrown up in a very haphazard manner, and beauty parlors and shops are often found in houses in residential districts.

A typical Chinese city has wide roads, cycle lanes, several universities, a number of technical institutes, hospitals and a medical school. Even mid-size cities have several million people, a skyline, an airport expressway, a large wall-off industrial zone and fancy condominiums. Benjamin Haas wrote in The Guardian: “Many people worry that many of these newly minted metropolises will lose their character — the Chinese government has set a target for 30 percent of buildings to be prefabricated in the next 10 years. Newly built apartment blocks already have a cookie-cutter feeling, with identical 30-storey buildings visible from the window of nearly every high-speed train ride. The uniform construction can create an eerie scene, one city indistinguishable from the next. [Source: Benjamin Haas The Guardian, March 20, 2017]

In China, prefecture level cities are usually broken up into smaller districts, counties, sub-cities, towns, and villages. Wade Shepard wrote in Forbes: “There is a fundamental difference between how China and the West define and utilize the term “city.” In China, “city” is more of an administrative term which is used to indicate that an expanse of land is under the auspices of a particular level of urban government. Under this construct, much of the land that falls under the authority of a municipality is actually urban in name only, and can often include large expanses of agricultural areas, mountains, forests, or deserts. This is how China can have “cities” the size of North Carolina. For example, Hulunbuir in Inner Mongolia is the largest municipal area in the world by size, being larger than New Zealand, but it is over 99 percent grasslands. This concept of what a city is means that contiguous urban areas can actually be divided between multiple distinct and separate governmental subsets. [Source: Wade Shepard, Forbes, April 23, 2016]

Major Cities in China

Beijing and Shanghai are the most important cities in China. Other important cities include Tianjin, a northern port and industrial center not far from Beijing; Guangzhou, the main southern port city; and Shenzhen, a major business and industrial hub near Hong Kong . Among the other major cities are Shenyang, Chongqing, Chengdu, Nanjing, and Wuhan. Less important but still important are Dalian, Zhengzhou, Hangzhou, Suzhou, and Xian.

The largest cities in mainland China by population of urban area:

1) Shanghai — 26,917,322 in 2020; 20,217,748 in 2010

2) Beijing — 20,381,745 in 2020; 16,704,306 in 2010

3) Chongqing — 15,773,658 in 2020; 6,263,790 in 2010

4) Tianjin — 13,552,359 in 2020; 9,583,277 in 2010

5) Guangzhou in Guangdong — 13,238,590 in 2020; 10,641,408 in 2010

6) Shenzhen in Guangdong — 12,313,714 in 2020; 10,358,381 in 2010

7) Chengdu in Sichuan — 9,104,865 in 2020; 7,791,692 in 2010

8) Nanjing in Jiangsu — 9,314,685 in 2020; 5,827,888 in 2010

9) Wuhan in Hubei — 8,346,205 in 2020; 7,541,527 in 2010

10) Xi'an in Shaanxi — 7,948,032 in 2020; 5,403,052 in 2010

11) Hangzhou in Zhejiang — 7,603,271 in 2020; 5,849,537 in 2010

12) Dongguan in Guangdong — 7,402,305 in 2020; 7,271,322 in 2010

13) Foshan in Guangdong — 7,313,711 in 2020; 6,771,895 in 2010

14) Shenyang in Liaoning — 7,191,333 in 2020; 5,718,232 in 2010

15) Harbin in Heilongjiang — 6,360,991 in 2020; 4,596,313 in 2010

16) Qingdao in Shandong — 5,597,028 in 2020; 4,556,077 in 2010

17) Dalian in Liaoning — 5,587,814 in 2020; 3,902,467 in 2010

18) Jinan in Shandong — 5,330,573 in 2020; 3,641,562 in 2010

19) Zhengzhou in Henan — 5,286,549 in 2020; 3,677,032 in 2010

20) Changsha in Hunan — 4,555,788 in 2020; 3,193,354 in 2010 [Source: Wikipedia]

[Source: Wikipedia]

As of 2005, the largest urban centers were Shanghai, 12,665,000; Beijing, 10,849,000; Tianjin, 9,346,000; Wuhan, 6,003,000; Chongqing, 4,975,000; Shenyang, 4,916,000; Guangzhou, 3,881,000; Chengdu, 3,478,000; Xi'an, 3,256,000; Changchun, 3,092,000; Harbin, 2,898,000; Dalian, 2,709,000; Jinan, 2,654,000; Hangzhou, 1,955,000; and Qingdao, 1,452,000. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Based on 2000 census data, the largest cities were the four centrally administered municipalities, which include dense urban areas, suburbs, and large rural areas: Chongqing (30.5 million), Shanghai (16.4 million), Beijing (13.5 million), and Tianjin (9.8 million). Other major cities were Wuhan (5.1 million), Shenyang (4.8 million), Guangzhou (3.8 million), Chengdu (3.2 million), Xi’an (3.1 million), and Changchun (3 million). China has 12 other cities with populations of between 2 million and 2.9 million and 20 or more other cities with populations of more than 1 million persons. [Source: Library of Congress]

Rapid Rise of Chinese Cities: 221 of Them with 1 Million People By 2025

There are 669 cities in China by one count. Of these there are 100 to 150 cities with a population over 1 million, depending on the estimate. In comparison the United States as nine. China will have 221 cities with 1 million or more in 2025, according to the consultancy firm McKinsey. In China there were less than 50 such cities in 1989. Many Chinese cities have gone from being Third World backwaters with outdoor markets and roads dominated by bicycles to modern cities with skyscrapers, shopping malls and traffic jams in record time. The pace of urban development is so rapid the artist Ai Weiwei told The Times that if you leave the city for a month you can barely find your own house when you return.

A typical city such as Changzhu had 700,000 residents in 1996 and 4 million in 2006 The number of towns is expected to grow in the next 15 years from 50,000 to 70,000. One of the newest Chinese cities with more than 1 million people is Taicang, a former fishing village 80 kilometers from Shanghai. In 2012 there a bustling shopping area in place were a road didn’t exist four years before. China, by varying estimates, has more than 100 cities with 1 million or more residents, The number of million-plus cities will reach 221 by 2035, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, an economics research firm. More than a dozen will have populations of 25 million or more each. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Nowhere is the scale of the country's transformation more vividly displayed than in its cities. Hundreds of millions of Chinese are moving from farms to urban centers to seek jobs and middle-class lifestyles. In Shanghai, whose population of 23 million exceeds that of Australia, high-rises sprawl in all directions until their silhouettes slip from view, obscured by brown haze...Yancheng, with a mere 8 million people, is a former salt-harvesting town on the northern bank of the Yangtze River near the coast. Bustling shopping districts, new office buildings, housing projects and other development extend in every direction. Away from the urban center, farms give way to neat rows of town houses and multistory condominiums. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas told the Christian Science Monitor: You also see the city being reinvented in China – or maybe not reinvented but reproduced at an enormous scale and speed. You also notice that things are changing by default. It is similar to the Roman system in which the elements and topology of a city are replicated in a new place and adapted around local conditions. I have seen cities there begin from scratch. Shenzhen, north of Hong Kong, was a fishing village in the 1980s and is now a city of over 10 million people. Shenzhen has become a unique city even though there is nothing physically unique about it. It is unique because it is next to Hong Kong; it acts [as] a counterpart, since it is also in a special economic zone with special emigration statues. Therefore, it attracts a lot of Chinese companies hoping to access a more reliable legal system. [Source: Project Syndicate, July 27, 2012]

Plastic palm trees

China Second and Third Tier Cities

Benjamin Haas wrote in The Guardian: China’s centre is moving west. Guiyang, for example, topped a few lists of the best-performing Chinese city in 2016, as the once-sleepy capital of the country’s poorest province saw a boom in cloud computer servers and telecommunications, with e-commerce giant Alibaba a major investor. Factories are moving inland from the coastal regions in droves. Xiangyang and Hengyang, both now home to more than 1 million people, are swelling as low-end manufacturing moves to cities with cheaper labour. The local government in Zhengzhou, for its part, transformed a dusty patch of land in central metropolis into an industrial park overnight; Foxconn, the world’s largest contract electronic manufacturer, now makes about half of all iPhones there and has also built a plant in Hengyang. [Source: Benjamin Haas The Guardian, March 20, 2017]

On his visit to Fuling, a city with about 1 million people, in 2013, Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “When you live in the Chinese interior, you realize how Beijing and Shanghai create an overly optimistic view of the country. But this is the first time I’ve wondered if Fuling might inspire a similar reaction. The city is under the jurisdiction of Chongqing Municipality, which receives more funding than other regions because of the dam. At the time of my visit, the top Chongqing official is Bo Xilai, who is known for having national ambitions. Along with his police chief, Wang Lijun, Bo has orchestrated a well-publicized attempt to crack down on crime and reform a corrupt police force. As part of this project, cities like Fuling have erected open-air police stations where officers must be available to the public at all times. This is hardly a new idea, but in China it feels revolutionary. I visit a few stations, which are busy handling the kind of problems that in the past often flared up as street fights. Everywhere I go, people tell me about Bo’s reforms, and I realize that I’ve never been anywhere in China where people speak so positively about their government. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, March 2013 ^^^]

“But you don’t have to travel very far to hear a different story. Poverty and isolation no longer characterize Fuling, but smaller cities and villages still face these challenges. Most of my former students live in such places, where they teach English in middle schools and high schools. Their letters remind me how far China still has to go: “Dear Mr. Hessler: I am sorry to tell a bad news. My town is called Yihe in Kaixian County in Chongqing. Two days ago, a big thunder hit my wife’s village school. It killed 7 students and wounded 44 students ... There used to be lightning rod ... but the school can not afford it.” ^^^

Small Chinese City in the 1990s and the Early 2000s

In the 1990s the Yangtze river town of Fuling had a population of around 200,000, which was small by Chinese standards. Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “ Fuling sits at the junction of the Yangtze and the Wu Rivers, and in the mid-1990s it felt sleepy and isolated. There was no highway or rail line, and the Yangtze ferries took seven hours to reach Chongqing, the nearest large city. Foreigners were unheard of — if I ate lunch downtown, I often drew a crowd of 30 spectators. The city had one escalator, one nightclub, and no traffic lights. I didn’t know anybody with a car. There were two cell phones at the college, and everyone could tell you who owned them: the party secretary, the highest Communist Party official on campus, and an art teacher who had taken a pioneering step into private business. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, March 2013 ^^^]

“In those days Fuling Teachers College was only a three-year institution, which placed it near the bottom of Chinese higher education. But my students were grateful for the opportunity. Nearly all of them came from rural homes with little tradition of education; many had illiterate parents. And yet they majored in English — a remarkable step in a country that had been closed for much of the 20th century. Their essays spoke of obscurity and poverty, but there was also a great deal of hope: “My hometown is not famous because there aren’t famous things and products and persons, and there aren’t any famous scenes. My hometown is lacking of persons of ability ... I’ll be a teacher, I’ll try my best to train many persons of ability.” “There is an old saying of China: ‘Dog loves house in spite of being poor; son loves mother in spite of being ugly.’ That [is] our feeling. Today we are working hard, and tomorrow we will do what we can for our country.” ^^^

“My students taught me many things, including what it meant to come from the countryside, where the vast majority of Chinese lived at the beginning of the reform era. Since then an estimated 155 million people have migrated to the cities, and my students wrote movingly about relatives who struggled with this transition. They also taught me about the complexities of poverty in China. My students had little money, but they were optimistic, and they had opportunities; it was impossible to think of such people as poor. And Fuling itself was hard to define. The Three Gorges Dam could never have happened in a truly poor country — Beijing reports that the total investment was $33 billion, although some unofficial estimates are significantly higher. But memories of recent poverty helped make the dam acceptable to locals, and I understood why they desired progress at all costs. My apartment was often without electricity for hours, and over-reliance on coal resulted in horrible pollution. ^^^

“In early 2001, the city’s first highway had been completed, rendering the Yangtze ferries obsolete. Two more new highways would follow, along with three train lines. Because of the Three Gorges project, large amounts of central government money flowed into Fuling, along with migrants from low-lying river towns that were being demolished. (All told, more than 1.4 million people were resettled.) In the span of a decade Fuling’s urban population nearly doubled, and the college was transformed into a four-year institution with a new campus and a new name, Yangtze Normal University. The student body grew from 2,000 to more than 17,000, part of the nation’s massive expansion in higher education. Meanwhile, Americans began to take new interest in China, and River Town became a surprise best seller. I heard that an unofficial translation was commissioned in Fuling, with access limited to Communist Party cadres. But I never learned how the government reacted to the book. ^^^

Competition Among China’s Cities

Daniel A. Bell wrote in the New York Times, “From the outside, China often appears to be a highly centralized monolith. Unlike Europe’s cities, which have been able to preserve a certain identity and cultural distinctiveness despite the homogenizing forces of globalization, most Chinese cities suffer from a drab uniformity. But China is more like Europe than it seems. Indeed, when it comes to economics, China is more a thin political union composed of semiautonomous cities — some with as many inhabitants as a European country — than an all-powerful centralized government that uniformly imposes its will on the whole country. And competition among these huge cities is an important reason for China’s economic dynamism. The similar look of China’s megacities masks a rivalry as fierce as that among European countries. [Source: Daniel A. Bell, New York Times, January 7, 2012. Bell is a professor at Shanghai’s Jiaotong University and Beijing’s Tsinghua University, and co-author of “The Spirit of Cities.”]

China’s urban economic boom began in the late 1970s as an experiment with market reforms in China’s coastal cities. Shenzhen, the first ‘special economic zone,” has grown from a small fishing village in 1979 into a booming metropolis of 10 million today. Many other cities, from Guangzhou to Tianjin, soon followed the path of market reforms. Today, cities vie ruthlessly for competitive advantage using tax breaks and other incentives that draw foreign and domestic investors. Smaller cities specialize in particular products, while larger ones flaunt their educational capacity and cultural appeal. It has led to the most rapid urban “economic miracle” in history.

But the “miracle” has had an undesirable side effect: It led to a huge gap between rich and poor, primarily between urban and rural areas. The vast rural population — 54 percent of China’s 1.3 billion people — is equivalent to the whole population of Europe. And most are stuck in destitute conditions. The main reason is the hukou (household registration) system that limits migration into cities, as well as other policies that have long favored urban over rural development. More competition among cities is essential to eliminate the income gap. Over the past decade the central government has given leeway to different cities to experiment with alternative methods of addressing the urban-rural wealth gap.

Rise of Chongqing

Reporting from Chongqing,Eric X. Li wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “A quiet revolution is happening in China’s hinterland. Breakneck growth spurred by government-led economic reforms has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty but also has brought about byproducts such as a large wealth gap and widespread corruption that threaten the sustainability of its development and social cohesion. Will China prosper or be brought down an ever-widening divide between the haves and the have-nots, with the latter dragging down the former?[Source: Eric X. Li, Christian Science Monitor, December 6, 2011. Eric X. Li is a venture capitalist in Shanghai and a doctoral candidate at Fudan University's School of International Relations and Public Affairs]

The answer may be found in this mountainous region deep inside China’s western interior — until recently one of the country’s most underdeveloped areas. In merely half a decade, the city-province of Chongqing, half the size of Britain, has become the largest laboratory of public policy innovation in the world today. Three sets of large-scale policy experiments interwoven by one revolutionary idea — growth with equity — are fast transforming this region with long-term implications for the future of China and beyond: urbanization, social fairness and market economics — based on unmistakably Chinese values.

Urbanization is taking place in a speed and scale unprecedented even by China’s standard. Of the 32 million inhabitants of Chongqing, only 12 million are city dwellers, with the remainder being peasants and migrant workers. Unlike the coastal regions that were mostly already urban at the beginning of China’s economic reform 30 years ago, Chongqing’s demographic is a mirror image of China at large. This makes urbanization qualitatively different from what has taken place in the country so far. In 2008, an Urban-Rural Land Exchange was established. This innovative system essentially securitizes rural residential dwellings, allowing farmers to turn their farmhouses back to arable land in exchange for cash from developers who purchase the square footage in the form of additional quotas for urban real estate development. Since the beginning of the exchange, $1.5 billion of transaction value has taken place, and more than 2 million peasants have moved into the city. Another 1 million are expected to make the transition by the end of 2012. An astonishing total of 7 million peasants are projected to move into the city by 2020, taking the urbanization rate to 60 percent. What is more remarkable is that this demographic shift is taking place without the loss of arable land.

As this social transformation is taking place, the government has stepped in aggressively to ensure the welfare of those who are at risk of being left behind by rapid economic development. Some 430 million square feet of low-income housing are being built, essentially guaranteeing affordable housing for the bottom third of the population. This is being done in its entirety from government-sourced funding, without relying on market forces.

Chongqing Reforms

Eric X. Li wrote in the Christian Science Monitor: The most impactful reform has been Chongqing’s pioneering of a system that automatically grants new city dwellers the much-coveted urban residency status and its accompanying education and health-care benefits five years after taking up city residence. In one fell swoop, the most intransigent and structural divide that separates all Chinese between city and rural residents, the Hukou system, is at last being breached. The heartbreaking scenes of millions of migrant workers toiling in rich coastal cities without health care and education for their children are being eradicated in the Chinese heartland. [Source: Eric X. Li, Christian Science Monitor, December 6, 2011.

To attack corruption, the government began with the hardest nut to crack — the pharmaceutical industry in the public-health sector. It is an open secret that rampant abuse and kickbacks plague the value chain throughout the country. A computerized pharmaceutical procurement system has been built, with mandatory participation by all public hospitals. On one screen, all drug purchases by public hospitals are shown with names of suppliers and unit prices on a daily basis, and open to the public real-time. This “sunshine drug purchase” program, as it is termed, has covered $5 billion of drug purchases in the 18 months since its launch, and is helping to regain public trust in Chongqing’s health-care system.

Open market economics forms the third pillar of Chongqing’s development. In 2007, only 25 percent of Chongqing’s GDP was generated by the private sector with the rest by the government and state-owned enterprises. Today, 60 percent is generated by private companies. This remarkable growth has in part been fueled by a daring experiment in micro-finance. As state banks concentrate their lending to state-owned enterprises, capital formation has been the bottleneck to the expansion of private small and medium enterprises (SMEs) across the country. In Chongqing, however, hundreds of government-approved and regulated private non-bank providers of micro-credit have lent $15 billion to private SMEs this year alone.

At the same time, government industrial policies are spurring large-scale developments in technology and manufacturing. The development model of the coastal regions of the Pearl River and Yangtze River deltas has been to encourage low-end assembly industries with the advantage of cheap labor and low-cost transportation by sea. Higher-value components in industries such as electronics are still being made overseas. Chongqing, at a transportation disadvantage, has opted to use government levers to enable rapid buildup of scale in downstream assembly. This is driving component makers to move their productions from overseas directly to Chongqing to realize the benefits of economy of scale. In the mobile computing and pads industry, current trends indicate a remarkable 80 percent of the value being made in the Chongqing region in the near future. By 2015, 100 million notebook computers and pads are to be made in Chongqing, the largest such production base in the world. HP and Foxconn are among the largest corporate investors. Foreign direct investments have grown from $1.2 billion in 2007 to $9 billion in the first three quarters of 2011.

Perhaps the most significant element of the Chongqing phenomenon is its underlying driver: public morality. A uniquely Chinese brand of socialism underpins its social and economic development. The “singing-red” movement — the revival of age-old Communist revolutionary music — reaffirms modern communitarian values that deeply resonate with Chinese culture’s Confucian roots. Only on the basis of a fair and just society can rapid economic development be justified and sustained. A strong government unapologetic of its leadership role is proving to be effective because it is consistent with the Chinese cultural tradition of honoring moral authority vested in political power. In an increasingly materialistic environment, the government, led by the Provincial Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, is reclaiming the moral high ground in society.

Chengdu Model of Empowering and Providing Benefits for Rural Residents

Daniel A. Bell wrote in the New York Times, “I recently visited a development zone composed of small firms that export fiery Sichuan chili sauces. Most farmers rented their land and worked in the development zone, but those who wanted to stay on their plots were allowed to. So far, one-third of the area’s farmland has been converted into larger-scale agricultural operations that have increased efficiency. [Source: Daniel A. Bell, New York Times, January 7, 2012. Bell is a professor at Shanghai’s Jiaotong University and Beijing’s Tsinghua University, and co-author of “The Spirit of Cities.”]

More than 90 percent of the municipality’s rural residents are now covered by a medical plan, and the government has introduced a more comprehensive pension scheme. Rural schools have been upgraded to the point that their facilities now surpass those in some of Chengdu’s urban schools, and teachers from rural areas are sent to the city for training.

Empowering rural residents by providing more job opportunities and better welfare raises their purchasing power, helping China boost domestic consumption. And in 2012, Chengdu is likely to become the first big Chinese municipality to wipe out the legal distinction between its urban and rural residents, allowing rural people to move to the city if they choose.

Chengdu’s success has been driven by a comprehensive, long-term effort involving consultation and participation from the bottom up, as well as a clear property rights scheme. By contrast, Chongqing has relied on state power and the dislocation of millions to achieve similar results. If Chengdu’s “gentle” model proves to be more effective at reducing the income gap, it can set a model for the rest of the country, just as Shenzhen set a model for market reforms.

There are fundamental differences, of course: Chengdu’s land is more fertile and its weather more temperate, compared to Chongqing’s harsh terrain and sweltering summers. Life is slower in Chengdu; even the chili is milder. What succeeds in one place may fail elsewhere. Ultimately, the central government will decide what works and what doesn’t. And that’s not a bad thing; it encourages local variation and internal competition.

Chengdu Model Vs. Chongqing Model

Daniel A. Bell wrote in the New York Times, “The most widely discussed experiment is the “Chongqing model,” headed by Bo Xilai, a party secretary and rising political star. Chongqing, an enormous municipality with a population of 33 million and a land area the size of Austria, is often called China’s biggest city. But in fact 23 million of its inhabitants are registered as farmers. More than 8 million farmers have already migrated to the municipality’s more urban areas to work, with a million per year expected to migrate there over the next decade. Chongqing has responded by embarking on a huge subsidized housing project, designed to eventually house 30 to 40 percent of the city’s population. [Source: Daniel A. Bell, New York Times, January 7, 2012]

Chongqing has also improved the lot of farmers by loosening the hukou system. Today, farmers can choose to register as “urban” and receive equal rights to education, health care and pensions after three years, on the condition that they give up the rural registration and the right to use a small plot of land.

While Chongqing’s model is the most influential, there is an alternative. Chengdu, Sichuan’s largest municipality, with a population of 14 million — half of them rural residents — is less heavy-handed. It is the only city in China to enjoy high economic growth while also reducing the income gap between urban and rural residents over the past decade. Chengdu has focused on improving the surrounding countryside, rather than encouraging large-scale migration to the city. The government has shifted 30 percent of its resources to its rural areas and encouraged development zones that allow rural residents to earn higher salaries and to reap the educational, cultural and medical benefits of urban life.

China’s Skyscraper Obsession

China’s is obsessed with vertical cities. At the end of 2015 one in three of the world’s 150-meter-plus skyscrapers was in China. Nicola Davison wrote in The Guardian, “Few people outside China have heard of Suzhou, a city in the eastern province of Jiangsu with a population of 1.3 million. Yet if all goes to plan, Suzhou will soon boast the world’s third-tallest building, the 700 meter Zhongnan Centre. Other Chinese cities joining the upward rush include Shenzhen, Wuhan, Tianjin and Shenyang. By 2020, China is set to be home to six of the world’s 10 tallest buildings, although none will top the globe’s current highest, the 828 meter Burj Khalifa in Dubai.” [Source: Nicola Davison, The Guardian, October 30, 2014 ***]

“Super tall towers are as much about prestige as commercial gain. In China they are also symptomatic of a central government policy that has led to the frantic densification of cities. Premier Li Keqiang has called urabanisation a “huge engine” for growth as the government attempts to restructure its economy away from a reliance on exports and investment to one based on domestic spending. While most people in China were farmers 30 years ago, 50 percent of people lived in cities by 2011 and by 2030 it’s estimated one billion people, or 70 percent of the population, will be urbanites. Getting cities wrong could create slums, exacerbate climate change and encourage social instability. ***

At the CTBUH [Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat] conference in Shanghai, architects agreed that sprawl is not a sustainable solution to density. But building towers of dizzying height in a never-ending game of architectural one-upmanship is impractical too. “We have to find the solution of how to move towards more density but to keep the human scale”, says Yosuke Hayano, principal partner of MAD Architects, a Beijing-based practice. “People are very sensitive to space.” MAD designs on a theory they call shan shui (“mountain water”), in reference to the way cities were strategically positioned in ancient China near rivers and mountains. The Zendai Himalayas Centre, a 560,000 sq m development in the eastern city of Nanjing due for completion in 2017, is a ring of undulating hill-shaped “towers” around a cluster of low buildings, with vertical louvres creating the impression of waterfalls. This mimicry of nature, MAD believes, imbues urban environments with humanity.” ***

See Separate Articles SKYSCRAPERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PUDONG AND SKYSCRAPERS AND FAST ELEVATORS IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; SHENZHEN: SKYSCRAPERS, MINIATURE CITIES AND CHINA’S FASTEST-GROWING AND WEALTHIEST CITY factsanddetails.com

Thirty -Story Hotel Built in a Month in China

Reporting from Changsha in Hunan Province, Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: China, In early December 2012, Liu Zhangning was tending her cabbage patch when she saw a tall yellow construction crane in the distance. At night, the work lights made it seem like day. Fifteen days later, a 30-story hotel towered over her village on the outskirts of the city like a glass and steel obelisk. "I couldn't really believe it," Liu said. "They built that thing in under a month." A time-lapse video of the project in Changsha shows the prefabricated building being assembled on site. "I've never seen a project go up this fast," said Ryan Smith, an expert on prefabricated architecture at the University of Utah. In other countries, the most advanced prefab construction methods can reduce building times by a third to half, Smith said. The builders of the Changsha hotel did better, knocking one-half to two-thirds off the normal schedule. "It's unfathomable," Smith said. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, March 7, 2012|]

The hotel will accommodate visiting clients of Broad Sustainable Building, the Chinese company behind the Changsha hotel, and house some of its employees. Raising a 30-story tower in two weeks is possible because most of the work is done in a factory and the foundation has been laid ahead of time. China's abundance of workers also helps. But a job done quickly is not always a job done well. Zhang said that in their race to the finish line, many Chinese construction companies skimp on the meticulous reviews and inspections that make projects in the West drag on for years. "Incredible speed also means incredible risk," he said. "But only time will tell how serious the risk is."

Broad Sustainable Building, says it cuts no corners on safety. To the contrary, it says, its methods will make China's construction boom safer, cheaper and more environmentally friendly. In promotional literature, Broad boasts that its technology is "the most profound innovation in human history" and that construction on a third of the world's new buildings will be done this way "in the near future."

The hotel, called T-30, looms over dilapidated concrete homes interspersed with piles of garbage and rows of cabbages and leeks. Dogs and chickens run through muddy alleyways. In mid-January, a month after the building's announced completion, its interior was a hive of activity. Many of the 500 rooms were finished, with made beds and white sofas. In others, wires protruded from unfinished walls. Paint-splattered workers hauled wooden planks past a grand piano in the pristine marble lobby. Zhang said it took about 200 of the company's 900 employees to put up the hotel. They are paid $500 to $800 a month, above average for China. Although some company executives acknowledged that many workers put in well over 40 hours a week, Zhang said they do not work later than 10 p.m.

The time-lapse video provides a glimpse of how the hotel was made. Workers in blue jumpsuits are seen assembling "main boards," the building blocks of Broad's structures — 13-by-50-foot slabs containing ventilation shafts, water pipes, electric wiring and lighting fixtures sandwiched between ready-made floors and ceilings. A counter at the bottom of the screen ticks off the hours as the boards are loaded onto a truck and delivered to the construction site. A crane then stacks them up like blocks. Workers bolt in pylons and piece together staircases; the glass and steel exterior rolls up onto the frame like a gleaming carpet. At 360 hours, the ticker stops.

Chinese Cities Overrun with Bad Copies of Foreign Architecture

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, ““New architecture, when it is notable, is nearly always by foreigners or copying foreign styles, a tendency that has led Western architects to flood into China, often with second-rate projects for sale. When some sort of indigenous style is attempted, as for example the now de rigeur recreation of one or two old streets, it is usually an attempt to evoke an idealized past rather than adhere to a particular historical idiom. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, June 6, 2013 ]

“These are not just individual buildings but entire streetscapes, with cobblestone alleys, faux churches (often used as concert halls), towers, and landscaping designed to reproduce the feel of European and North American cities. The city of Huizhou features a replica of the Austrian village of Hallstatt; while Hangzhou, a city famous for its own waterfront culture, now includes a “Venice Water Town” that has Italian-style buildings, canals, and gondolas. Other cities in China now feature Dutch colonial-style townhouses, German row houses, and Spanish-style developments.

“What drives this obsession with foreign styles? Bianca Bosker gives some answers in her fascinating new book, “Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China.” Bosker focuses on the suburbs for the upper class that began to be built in the late 1990s, following the privatization of real estate... One reason, Bosker argues, is that replicas are highly valued in Chinese culture — copies and mimicry of the innovations of others do not carry any negative connotations. In small doses, this idea has some validity. Great Chinese painting or calligraphy masters typically used to pattern their work on those who went before, only creating distinctive works later in their career. But it’s too glib to say that the sort of second-rate reproductions being built in Chinese cities have ever been accepted in Chinese or Asian culture. Copying was an homage, done at a high level, and a precursor to true creation. One thinks, perhaps of how Japanese jazzophiles curated and reissued classic American LPs that had gone out of production in the 1970s. These were made to the highest standards and implied true connoisseurship, rather than a superficial understanding of the genre.

“This is quite different from the subdivisions, which use some expensive accoutrements (Italian marble, French chandeliers, American carpets) as selling points, but which are instantly recognizable as poor imitations. As Bosker notes, the buildings disregard the original proportions in order to emphasize the monumental size of some features, such as towers or clocks — a cartoonish vision. (Fascinatingly, almost all of the suburbs Bosker studies are designed by Chinese architects for wealthy Chinese clients; some foreign architects were tried but they represented their home countries as they saw them, not in the historical pastiche that the developers wanted for their clients.) This is hardly in the spirit of another traditional Chinese cultural practice — of copies that change the original but keep its essence. Instead we have the West as marketing gimmick.

“Indeed, Bosker’s most convincing explanation for the developments is economics: Chinese tend to identify their culture with decline — old buildings call to mind China’s poverty and backwardness, not its glory; whereas achieving Western standards of living has been held up as a primary goal of modernization. So for developers, copying foreign towns became one way to gain cachet and jack up the price, especially as the new rich in China were beginning to travel abroad more widely and gain familiarity with these styles...Part of the reason that fakes have an appeal in China is that the country lacks cultural self-confidence. China’s leaders want to turn the country into a cultural superpower but they still manage intellectual life too tightly to allow for the free flow of ideas that would require.”

Book: Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China by Bianca Bosker, University of Hawai‘i Press.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2021