TULOU

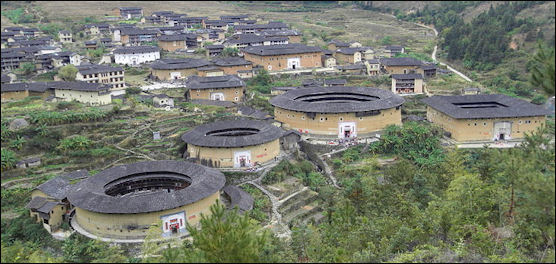

Tulou (also spelled Tu Lou) is a type of Chinese rural dwellings of the Hakka and Minnan people . Because Hakka people like to live together in remote mountainous and forested regions, they built fortified houses to defend themselves against bandits and wild animals. Tulou (“earth buildings”) are large circular edifices that resemble fortresses in the remote hills of southeastern Fujian Province. They were built by the Hakka after they arrived in Fujian from Henan Province, where they had been persecuted. The tulou are quite impressive and are a popular destination among tourists. There are several thousand of them in Yongding county alone.

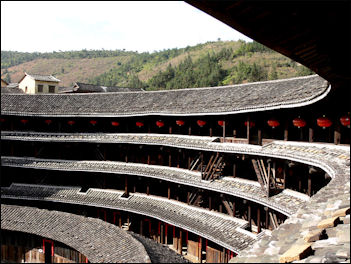

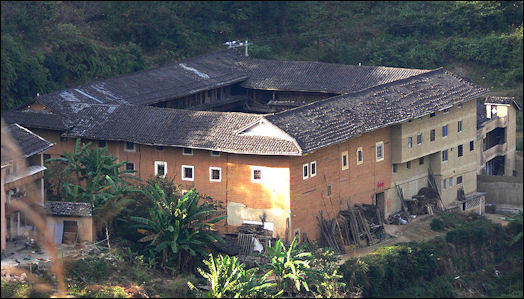

Traditionally, tulous were built of compacted earth with very thick walls made from sand, earth and mud and pebbles bound together with glutinous rice and brown sugar. Later some were built with granite or fired bricks.The structures were built on a stone base and supported on wooden poles. The thick walls were packed with dirt and internally fortified with wood. Many housed more than 100 people. Some housed more than 300. . Dozens of rooms were built inside the walls and the central area functioned as a courtyard. On the ground level, animals lived side by side with the occupants, and families conducted daily tasks such cooking food and cleaning clothes in a common area. Tulous have often been constructed in clusters. Multiple generations and branches of a family traditionally occupied a single tulou. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Lu Na, China.org, May 9, 2012]

The Hakka were basically a fishing people. They used the fortified houses in the remote hills to escape persecution. The unique architecture of the tulou, which includes a single entrance and gun holes, was developed as a defense against bandits and enemy villages. The first Tulou appeared during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and the building style developed over the following dynasties until reaching its current form as found during the period of the Republic of China (1912-1949). Its design incorporates the traditions of Feng shui, showing a perfect combination of unique traditional architecture with picturesque scenery.

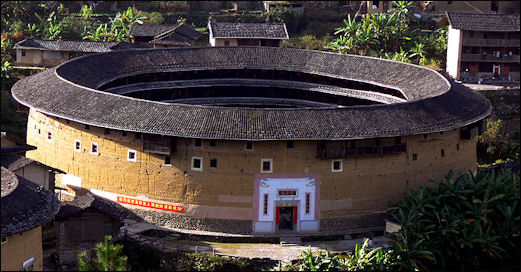

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Since the 12th century, the Hakka and Minnan people in Fujian province have concealed and protected themselves inside tulou, rammed-earth apartment complexes lined with wood-framed rooms facing a communal courtyard. Each clan would build its own tulou over a period of years; some are small, housing only a few dozen people, others can hold more than 500... From the sky, some are shaped like doughnuts. Others take the form of squares and ovals. The structures are so strange and fantastic that American intelligence officers analyzing satellite images during the Cold War initially suspected they were missile silos or part of a nuclear complex. From the ground here in southeastern China, though, it’s clear these fortresses — with thick walls and a single, heavily fortified entrance — were designed not for offense, but for defense. And they’re hardly modern technology.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

Tu Lou Area of Fujian Hours Open: 8:00am-10:00pm Admission: Nanjing Tulou: 100 yuan (US$15.73) per person; Yongding Tulou: 90 yuan (US$14.16) per person; Hua'an Tulou Cluster: 90 yuan (US$14.16) per person. [Source: China.org] Getting There: take the railway from Guangzhou City to Zhangzhou City, Yongding County and then take a bus to Tulou (less than 25 yuan per person); Websites: Hakka Houses flickr.com/photos ; UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO

See Separate Article HAKKA HISTORY AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; HAKKA LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Fujian's Tulou: A Treasure of Chinese Traditional Civilian Residence” by Hanmin Huang Amazon.com; “China Photography Book: Xiamen • Gulangyu • Tulou” by Paul Su Amazon.com; “Living in Heritage: Tulou as Vernacular Architecture, Global Asset, and Tourist Destination in Contemporary China” by Lijun Zhang Amazon.com; “Hakka Soul: Memories, Migrations, and Meals” by Woon Ping Chin Amazon.com; “The Hakka Cookbook: Chinese Soul Food from around the World” by Linda Lau Anusasananan , Alan Chong Lau, et al. Amazon.com; “Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad” by Nicole Constable ; “The Hakkas of Sarawak: Sacrificial Gifts in Cold War Era Malaysia by Kee Howe Yong Amazon.com; “A Hakka Woman's Singapore Story” by Lee Wei Ling Amazon.com

Fujuan Tuluo: UNESCO World Heritage Site

oval tulou Fujian Tulou were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008: “Fujian Tulou is a property of 46 buildings constructed between the 15th and 20th centuries over 120 kilometers in southwest of Fujian province, inland from the Taiwan Strait. Set amongst rice, tea and tobacco fields the Tulou are earthen houses. Several storeys high, they are built along an inward-looking, circular or square floor plan as housing for up to 800 people each. They were built for defence purposes around a central open courtyard with only one entrance and windows to the outside only above the first floor. Housing a whole clan, the houses functioned as village units and were known as “a little kingdom for the family” or “bustling small city.” They feature tall fortified mud walls capped by tiled roofs with wide over-hanging eaves. The most elaborate structures date back to the 17th and 18th centuries. The buildings were divided vertically between families with each disposing of two or three rooms on each floor. In contrast with their plain exterior, the inside of the tulou were built for comfort and were often highly decorated. They are inscribed as exceptional examples of a building tradition and function exemplifying a particular type of communal living and defensive organization, and, in terms of their harmonious relationship with their environment, an outstanding example of human settlement. [Source: UNESCO]

“The Fujian Tulou are the most representative and best preserved examples of the tulou of the mountainous regions of southeastern China. The large, technically sophisticated and dramatic earthen defensive buildings, built between the 13th and 20th centuries, in their highly sensitive setting in fertile mountain valleys, are an extraordinary reflection of a communal response to settlement which has persisted over time. The tulou, and their extensive associated documentary archives, reflect the emergence, innovation, and development of an outstanding art of earthen building over seven centuries. The elaborate compartmentalised interiors, some with highly decorated surfaces, met both their communities’ physical and spiritual needs and reflect in an extraordinary way the development of a sophisticated society in a remote and potentially hostile environment. The relationship of the massive buildings to their landscape embodies both Feng Shui principles and ideas of landscape beauty and harmony.

The site is important because: 1) The tulou bear an exceptional testimony to a long-standing cultural tradition of defensive buildings for communal living that reflect sophisticated building traditions and ideas of harmony and collaboration, well documented over time. 2) The tulou are exceptional in terms of size, building traditions and function, and reflect society’s response to various stages in economic and social history within the wider region. 3) The tulou as a whole and the nominated Fujian tulou in particular, in terms of their form are a unique reflection of communal living and defensive needs, and in terms of their harmonious relationship with their environment, an outstanding example of human settlement.

“The authenticity of the tulou is related to sustaining the tulou themselves and their building traditions as well as the structures and processes associated with their farmed and forested landscape setting. The integrity of the tulou is related to their intactness as buildings but also to the intactness of the surrounding farmed and forested landscape — into which they were so carefully sited in accordance with Feng Shui principles. The legal protection of the nominated areas and their buffer zones are adequate. The overall management system for the property is adequate, involving both government administrative bodies and local communities, although plans for the sustainability of the landscape that respect local farming and forestry traditions need to be better developed.”

Yonding

Yonding (southwest Fujian, on the border with Guangdong, accessible by bus from Longyan) is a difficult-to-reach place in southwestern Fujian famous for tulou. The tulou are quite impressive and are a popular destination among Japanese tourists. Yongding reportedly has more than 4,000 tulou but that is really a huge overestimate. Some are circular, some square while others are shaped like amphitheaters. The exotic earthen dwellings were unknown for many years. In 2008 they gained recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. [Source: Foong Thim Leng, The Star (a Malaysian newspaper), February 15, 2011]

Tours from Xiamen visit the tulou in Nanjing and Yongding. Nanjing county, established in 1356, is a three-hour drive from Xiamen. Large coach stop at the Tourist Reception Centre; from there, visitors continued in a smaller coach. On the winding mountain road, visitors can see terraced farms, rivers, and villages on the slopes and beside small streams on both sides of the road. Earthen building can occasionally be seen.

At Yuchang the ground floor corridor of the tulous are occupied by stalls selling all kinds of souvenirs and food. In Zhencheng there are stalls selling souvenirs, artwork, Chinese tea, herbs and pickled vegetable, a specialty of the region. From the Zhencheng building, an ancient cobblestone path continues along the mountain stream. On either side of the path are earthen buildings scattered along the riverside and in the open country. Large banyan trees provided shade stone benches, where people can stop for a rest. There is also a small local temple dedicated to Mazu, the sea goddess.

Tuluo and Myths About Them

Tulou in a Mandarin word. Most of the earthen buildings are circular, square, or phoenix-shaped (mansion style). Others are oblong, in the shape of the Eight Trigrams or crescent-shaped. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “The gargantuan buildings are so iconic that they appear on a Chinese stamp. The most famous have distinctive round shapes, appearing from a distance like flying saucers that have plopped down in the middle of farm fields. Some were reportedly mistaken for missile silos by American officials poring over satellite images.: [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

UNESCO, the United Nations agency that oversees cultural preservation, declared 46 tulou together to be a World Heritage Site in 2008. A UNESCO museum in one of the tulou says the structures were built between the 13th and 20th centuries. One exhibit says there are 30,000 tulou in Fujian Province, more than 20,000 of those in Yongding County. Others are concentrated in Nanjing and Hua’an counties.

Huang Hanmin, a scholar of the tulou who lives in Fujian, told the New York Times that many of the claims made about tuluo are myths, including the number. He said his research showed there were only 3,000 tulou in the province. A report by Global Heritage Fund, a preservation organization based in California that has a tulou project, gives the same number. Mr. Huang said about 1,100 are round, the kind that appear on stamps, postcards and tourism posters. The rest are square or rectangular. Another myth, he said, is that the tulou were all built by the Hakka. They were also built by the ethnic Minnan people of rural Fujian Province. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

square tulou

History of Tuluo

Hakka groups often feuded among themselves and with Yue (Cantonese) groups that occupied separate villages in the same areas. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ As a result of their often hostile relations with other groups, Hakka architectural style often differed from that of their Chinese and non-Chinese neighbors. In southwestern Fujian and in northern Guangdong, Hakka built circular or rectangular, multistoried, fortresslike dwellings, designed for defensive purposes. These Hakka “roundhouses" were built three or four stories high, with walls nearly a meter thick, made of adobe or tamped earth fortified with lime. The structures vary in size; the largest, resembling a walled village, measures over 50 meters in diameter. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 ]

According to legend that Hakka left their elderly left their homes behind and travelled in grief and despair across the Yellow River and the Yangtze with their clothing, valuables, pots and pans, poultry, horses and pigs, and the bones of their ancestors kept in jars. As they traversed the high mountain ranges of southwestern Fujian, they had to endure harsh weather conditions, and fend off attacks by wild animals and raids by bandits. After years of wandering, the weary Hakkas finally found a valley where they could build a new life. They cleared the land and worked from dawn to dusk to construct their earthen houses with clods of earth. [Source: Foong Thim Leng, The Star (a Malaysian newspaper), February 15, 2011]

The Hakka clan elders decided to build a home with a large courtyard that would allow clan members to live closely together. Building materials consisted of red soil mixed with strips of bamboo, sand and stone, a watery glutinous rice paste, brown sugar and egg whites. The earliest of the extant earthen buildings were constructed more than 1,200 years ago in 769 during the Tang dynasty (618-907). Many of the earthen dwellings date from the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties. Structures from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) can be seen everywhere. Of course, most were built between the time of Qing dynasty’s Kangxi emperor (1661-1722) and the 20th century.

The tulou scholar Huang Hanmin, said that the people living in the tuluo area of Fujian before the Hakka — people who mostly speak a language called Minnan — also constructed many tulou for security. “Historically the Hakka people and Minnan people didn’t live peacefully side by side,” he told the New York Times. ‘so safety became a paramount issue...The Minnan ones are older, and there are probably more of them,” he added. The Minnan people also built some of the largest tulou, with diameters of nearly a tenth of a mile.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

Chinese officials tried smashing the clan system during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and “70s. Collectives built more and more tulou and randomly assigned people to live in the buildings, so that each clan would have members spread among different collectives. When the Cultural Revolution ended, people drifted back to their clans.

Chuxi tulou cluster

Tuluo and the Hakka Clan Lifestyle

Traditionally, everyone living in the tulou would share a family name, with the building providing both a haven from bandits and a sense of community."The tuluo — are the ultimate architectural expression of clan existence in China,” Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times.” For centuries, each building... would house an entire clan, virtually a village. Everyone living inside would have the same surname, except for those who had married into the clan. The tulou usually tower four floors and have up to hundreds of rooms that open out onto a vast central courtyard, like the Colosseum. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

"The thick outer walls, made of rammed earth, protected residents against bandits. The forms vary. Many are square, resembling medieval keeps. With stockpiles of food, people could live for months without setting foot outside the tulou. But as the clan traditions of China dwindle today, more and more people are moving out of the tulou to live in modern apartments with conveniences absent from the earthen buildings — indoor toilets, for example."

Chengqi Lou Tulou

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “Perhaps the most famous tulou is the 17th-century Chengqi lou, which has striking concentric rings of homes and alleys on its ground floor... Its diameter is almost as long as a football field, and it has 402 rooms. (The smallest tulou in Fujian has just 16 rooms.) Fifteen generations have lived in it. Four brothers together oversaw building of the Chengqi lou for their families; it took four years to build, one year for each floor.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

“In the center is an ancestral altar, which is common to tulou” Wong wrote. “The inner ring of buildings once housed classrooms. Now children go outside for school. The next ring has 36 meeting rooms. The outermost ring is the main residential section of the tulou. In a design typical of tulou, that ring’s towering walls have kitchens and animal stalls on the ground floor, storage rooms on the second and homes on the third and fourth floors. Water is drawn from two wells. The people here are surnamed Jiang. Their ancestors migrated from Henan Province.”

Tianluoken and Zhencheng Touluo

In Taxia there is a square tulou surrounded by four circular ones. Known as the Tianluokeng complex it has gained World Cultural Heritage status and is commonly referred to as “four dishes, a soup.” According to tourist guides the founder of Tianluokeng was from Aoyao in Yongding on the other side of the mountain. According to genealogical records, his name was Huang Baisanlang. He chose to settle in Taxia because of its favorable fengshui. Huang scraped together a fortune raising ducks to build the earthen dwellings. Another story was that a fairy fell in love with him and helped him build the earthen buildings.[Source: Foong Thim Leng, The Star (a Malaysian newspaper), February 15, 2011]

The square-shaped tulou named Buyun was constructed in 1796. It has three storeys with 26 rooms on each floor. The circular building called Hechang is on Buyun’s right. It also has three storeys with 22 rooms on each floor. In 1936, both Buyun and Hechang were burned down by bandits and were rebuilt in 1953. The other circular building, Zhencheng, was built in 1930, while Ruiyin was built in 1936. Both are three storeys high with 26 rooms on each floor. The last building, Wenchang, was constructed in 1966. It is oval-shaped and like the others, has three storeys with 32 rooms on each floor.

The Zhencheng building is a famous tulou in Hongkeng village in Yongding. Zhencheng stands on 500sqm of land and was built by a descendant of Lin Zaiting, who was the 19th generation of the Lin clan in Hongkeng village. During the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) Lai Zaiing took his three sons to seek shelter in Fushi in Yongding, and to learn to be blacksmiths making tobacco cutters. Later the Lin brothers returned to Hongkeng and established the first factory producing tobacco cutters. They became rich and opened shops in Guangzhou, Shanghai and other major cities.

They first built Fuyu, a mansion-style square earthen building. Later one of the brothers, Lin Renshan, built Zhencheng. The couplet on the main door of Zhencheng reads: “Establish principles and discipline; bring about virtue and talent”. Zhencheng is shaped like the Eight Trigrams, with inner and outer rings. The four storeys of the outer rings are 16m high and have 184 rooms. The two storeys of the inner ring have 32 rooms. The outer ring is divided into eight large sections. After going through the two massive doors of the two rings, we reached the ancestral hall which the residents used for weddings, funerals or festivals. Part of the compound has been converted into a hotel.

Round tulou

Slanting Pillars of Yuchang

Xiaban is a village 4 kilometers away from Tianluokeng. Twelve earthen buildings are scattered on both sides of the river. The most famous earthen building here is Yuchang. It is famous for its slanting supporting pillars in the corridor on the third and upper floors. The pillar with the biggest tilt slanted at 15̊. Guides reassure visitors us that the building was in no danger of collapsing after surviving the elements and even earthquakes for more than 600 years. [Source: Foong Thim Leng, The Star, February 15, 2011]

The construction of Yuchang began in the middle years of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) through the cooperation of the Liu, Luo, Zhang, Tang and Fan families. The building has five storeys with 54 rooms on each floor. It is divided into five large units, each with its own staircase. The ancestral hall is located in the middle of the courtyard.

Why the slanting pillars? One guide said the five families took turns to provide meals for the masons and carpenters during construction but they were not well coordinated. Yuchang was originally a seven-storey building. A fire broke out before work was completed. A group of outsiders had come to pay respects to their ancestors at the tombs behind the building. However, the wind blew some of the burning hell notes into the building and set fire to the pillars on the seventh floor.

The Yuchang residents, the guide said, considered it a bad omen, and so the sixth and seventh floors were done away with. He said the residents later noticed that the supporting pillars in the corridors on the third and higher floors were slanted and they became fearful that the building would collapse...At dusk a tiger wandered into the building and moved along the corridors like a high-ranking official during inspection. Then it jumped from a rear window and escaped into the woods behind. That night the residents heard the tiger’s roar.

The Lius interpreted the roar as a congratulatory message from the tiger on the completion of the building. However, the other four families thought it was an inauspicious omen and they sold their units to the Liu family and moved to other villages. Some sailed across the ocean to South-East Asia,” He said the Liu family carefully investigated the tilting girders and pillars and found that the building was sound and in no danger of collapsing. Today, more than 100 people still live in the building.

Snail pit tulou

Tulou Tourism and Tulou Decline

Forty-six of the most spectacular tulou were added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2009. They were built between the 1300s and the 1960s with oldest being 600 years old. Some of the older ones have been earmarked for restoration. Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The United Nations designation has brought a wave of tourists to this largely agricultural region, where residents now hawk tea, tobacco, herbs and handicrafts to visitors, charging them about $1 to poke their heads into their homes. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015]

A developer is building Tolou-style apartment buildings in Guangzhou that has a circular shape, 245 apartments, a small hotel, shops and a health club.

Almost as quickly as tourists are pouring in to see them residents are leaving the Tulou and moving to new brick and tile houses. Some Tulou have only handful of people living in them in. Others are so deteriorated they have been deemed unsafe to live in. One elderly woman who left one told the Times of London, “If anyone can afford to, then they move out. They want homes with lavatories and bigger rooms.” Another said “only people without money” continue to live in the Tulou.” Without residents to do maintenance the Tulou deteriorate quickly, The walls crack and chips fall off. Wooden poles rot.

“The construction of tulou ended last century,” Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times. “The art of building them is fading. The United Nations is seeking to shield those that survive from the ravages of time. Some scholars contend that Chinese officials — though they promote the tulou as tourist attractions, and President Hu Jintao visited them during the 2010 Lunar New Year festivities — have done little to systematically preserve the buildings or modernize them so people will continue living in them.” People don’t clean it anymore,” said Jiang Qing, 28, as she stood on an upper balcony in Huan Xing tulou, whose name means “embracing prosperity.” “As long as people live here, the ecosystem thrives. Once people move out, then it all falls apart.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

Last Tulou Residents

Reporting from Tianzhong, the home of some of the last tulou residents, Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Amid rising incomes and expectations, residents — especially young couples with children — are abandoning the tulou way of life.They’re building boxy concrete homes with more privacy and modern amenities such as indoor plumbing and air conditioning. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

“Huang Maoyou, 67, and Xiao Dashi, 73, cling to the simple life in their 400-year-old tulou. They’re the only residents left in the two-story building, which has more than a dozen rooms. Many tulou proudly bear appellations over their doorways, such as Dragon’s Den or Five Phoenixes, but the entryway of the aging couple’s home is adorned with a smiling portrait of Mao Zedong. The sun has bleached the chairman’s once-red sun halo to a faint shade of peach. \~\

Hakka gun for defense

“Just inside the threshold of the fortress, a rough-hewed timber and stone gristmill is covered with dust. In the cobblestoned courtyard, Huang drew water from a well lined with green fern fronds and put a kettle on her outdoor stove. A group of foreigners on a bicycle tour had dropped by, and Xiao was eager to pour them some local tea from his pink Mickey Mouse thermos. “My sons and daughter have all moved to the city, but I can’t stand to live there,” said Xiao, who refuses money from his visitors. “I can’t read, and I prefer to stay here and work in the fields.” Xiao thinks that he and his wife will be the last inhabitants of his tulou, but he’s unperturbed. “It’s just the way life is,” he said, shrugging. Xiao was born in a nearby tulou that’s now abandoned. Fujian’s lush and aggressive tropical foliage has wasted no time moving in and is quickly swallowing the structure. \~\

Huan Xing is a typical tulou in Yongding County. It is 500 years old. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: "Chickens saunter across the grounds. Wooden pillars along the balconies were erected long ago at leaning angles to give the structure greater strength. The tulou once housed 100 families, but only 10 or so people live here now,” Wong wrote. “The elderly residents shuffle back and forth, cooking in kitchens on the first floor or sitting around the central courtyard chatting. One afternoon, they were moving firewood stacked outside the front entrance of the tulou to nearby storage sheds; the local government had asked them to do this to hide the messy stacks from tourists. The young have all moved out. Many live two hours away in the coastal city of Xiamen, where they largely do menial work.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 22, 2011] “Ms. Jiang, the mother of a 3-year-old child, moved here from another village when she married into the Li clan. She was used to tulou living — she had grown up in a square one herself. She and her husband recently moved out of Huan Xing to an apartment with running water and indoor plumbing. Her husband’s parents still live in a tulou, a ramshackle one across the street.”

“People used to live in the tulou for safety, but that’s not needed anymore,” said the husband, Li Jingan, 28, a restaurant owner. “A lot of people have gone elsewhere — Hong Kong, other places, they’re everywhere,” said Li Jiulan, 53, a woman who has lived in Chengqi lou for 32 years. “But it doesn’t matter if young people don’t live here. The older people are still here.” Mr. Huang, the scholar, had a different take: “What they’ve preserved is just the structure, but the people have all moved out,” he said. ‘so the living part has died. You’re just preserving a relic.”

Tulou Preservation

Chengqilou gun hole

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Academics, preservation groups and residents say the clock is ticking on tulou living. Figuring out a way to preserve both the physical structures and the intangible cultural and social heritage imbued in buildings inhabited by sprawling clans over centuries is a major challenge. Five years ago, the Global Heritage Fund, based in Palo Alto, Calif., initiated a tulou preservation project, but its efforts stalled amid a dearth of strong local partners. The organization hopes to revive the effort in the new year. “The ideal situation is to have people still live in them, but how do you convince people to live in a five-story mud house?” said Vincent Michael, the group’s executive director. “It doesn’t have as much cachet these days.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

“In 2008, the 30 largely interrelated families who jointly owned” a tulou called Qingxing “agreed to lease it long term to a Seattle-based Chinese-American family. During Mao’s 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, the U.S. family’s patriarch, then a teenager, had been sent to work in Tianzhong and developed close ties with residents of the tulou. “Every year, my family would go back to visit and see there were fewer and fewer people to maintain it. My mother, who studied architecture and is sort of a sustainable buildings adviser, had the idea to try to preserve it,” said Dana Wu, 26, an architecture student at Harvard. “My mom thought we could keep the building alive by reusing it.” \~\

“The dozen or so mostly elderly residents still living in the building — erected between 1950 and 1961 — were allowed to stay on. Wu’s parents repaired some of the wood in the tulou and added modern bathrooms on each floor. Creating a nonprofit called Friends of Tulou, the family now invites small groups of scholars and students to stay from time to time in about 50 guest rooms. The tulou has also hosted company retreats and theatrical performances; visitors make donations to contribute to the upkeep. Travelers are free to explore the building’s ancestral hall (which doubles as a bike parking zone), ramble through its wooden corridors and chat with its resident grandmothers as they work in their courtyard kitchens.” \~\

Difficulties of Tulou Preservation

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “But even with its updates, Qingxing can appeal to only a certain set of travelers: the ones who find charm in the screech of Chinese opera blaring from a resident’s TV and tolerate the odor of chamber pots, still favored over contemporary commodes by the tulou regulars. “We’re a nonprofit but so far, it’s probably more accurate to say we’re a profit-losing corporation,” Wu said. “We have people there every few months, but we’re deliberately moving slowly because we don’t want to overwhelm the community.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

“Even the more business-minded say repurposing tulou is financially challenging. Jian Xuezhen converted the Wind Cloud tulou in Kanxia village more than a year ago into a hotel, spending several hundred thousand dollars to add bathrooms, hot water and even Wi-Fi. He charges $15 to $20 a night for a room, but hasn’t seen many guests outside peak holiday times such as National Day in October and Chinese New Year. “I’ve lost some money already,” Jian said. Some nights, the only person in the building is an 89-year-old woman whom Jian allowed to stay on when he acquired the building. \~\

Tulou Tourism

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “One man who’s making a go of things is Stephen Lin, a sixth-generation inhabitant of the Fuyu tulou in Hongkeng village, 14 miles from Tianzhong, near a cluster of UNESCO-registered buildings. Lin’s 134-year-old building has 160 rooms; one wing with 19 rooms has been converted into a hotel, and 50 other clan members occupy the rest of the structure. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, January 3, 2015 \~]

Lin’s family got into the innkeeper business 12 years ago, and his clientele is 40 percent foreigners and 60 percent Chinese. The structure’s architecture, he noted, keeps visitors and permanent residents relatively separate, but guests like the idea of staying not in a “hotel-hotel, but a real living tulou.” Bruce Foreman, who runs a cycling tour group called Bikeaways and has visited the region more than a dozen times, agrees. “I really like to see authentic tulou with people still living in them, that human connection to the past,” he said. “If you want to see that, you’ve got to get there within the next 10 years and you’ve got to get off the beaten track. Don’t follow the bus route.” \~\

Image Sources: Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022