HAKKA

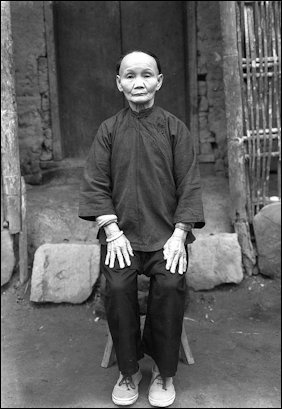

Hakka woman

The Hakka refer to a branch of the Han Chinese people that originated in the Huanghe River (Yellow River) valley and migrated southward settling mostly in Guangdong, Jiangxi and Fujian provinces in China, but also Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, and later migrated overseas. In China, they are particularly associated with Guangdong and Fujian Provinces. Many of the Chinese in Taiwan and Hong Kong—as well as those in Suriname, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, East Timor and Myanmar—are descendants of Hakka migrants. There are many Hakka in Britain and the United States. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Hakka (Pronounced HAHK-uh) are not a separate ethnic group. They are considered a Han Chinese group like the Cantonese, Sichuanese or Shanhaiese and their language is considered a southern Chinese dialect. However, the have a distinct history and identity. The name Hakka is the Cantonese (Yue) pronunciation for the word is pronounced “Kejia" in Mandarin Chinese. Because the Hakka are not considered an ethnic group, but are regarded as Han Chinese they have no special minority status in the People's Republic of China. Hakka have same rights accorded to all Chinese citizens. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Hakka are known for the pugnacity, ability to make money, clannishness., diligence, respect for the teachings of their ancestors, and commitment to education. They are considered a stable branch of the Han nationality with distinct characteristics rather than a separate ethnic group. The term "Hakka" comes from Guangdong dialect "Ha Ka" (Hakka), meaning "the guest" or "the customer", a name first used to distinguish the Hakkas from the local indigenous people. Some interpret Hakka as meaning “guest people” or ‘stranger families.” They are called guests because they began migrating to southern China from the Yellow River basin in the fourth century to escape war and natural disasters.

The Hakka are also known as Haknyin, K'e-chia, Kejia, Keren, Lairen, Ngai and Xinren. In Southeast Asia, Taiwan and elsewhere around the world, Hakka have developed a strong sense of communal identity, separate from other Chinese migrant populations, and some scholars define the Hakka as distinct from other overseas Han Chinese. The global Hakka diaspora has generated interest in Hakka history and culture. In September 1971, the first World Hakka Conference was held. As of 2010, more than 20 World Hakka Conferences had been held and “Hakkaology," is now recognized field. ++

See Separate Articles: HAKKA LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com TULOU: HAKKA GROUP HOUSES OF FUJIAN PROVINCE factsanddetails.com ; HAKKA IN TAIWAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad” by Nicole Constable Amazon.com; “Hakka Soul: Memories, Migrations, and Meals” by Woon Ping Chin Amazon.com; “Fujian's Tulou: A Treasure of Chinese Traditional Civilian Residence” by Hanmin Huang Amazon.com; “Living in Heritage: Tulou as Vernacular Architecture, Global Asset, and Tourist Destination in Contemporary China” by Lijun Zhang Amazon.com; “The Hakkas of Sarawak: Sacrificial Gifts in Cold War Era Malaysia by Kee Howe Yong Amazon.com; “A Hakka Woman's Singapore Story” by Lee Wei Ling Amazon.com

Hakka Population and Where They Live

The Hakka are the most diasporic of the Chinese community groups and their worldwide population is estimated to between 80 million and 120 million, with about 60 percent of these in Guangdong. The number of Hakka language speakers is significantly less. Hakka who live in Guangdong comprise about 60 percent of the total Hakka population. Worldwide, over 95 percent of the overseas-descended Hakka came from the Guangdong region, usually from Meizhou and Heyuan. Hakka there live mostly in the northeast part of the province, particularly in the so-called Xing-Mei (Xingning-Meixian) area. Jiangxi contains the second largest Hakka community. [Source: Wikipedia]

Where the Hakka live in China

Coming up with good population figures is difficult as defining Hakka is hard and there as been so much intermixing with other groups. There are about two million Hakka in Taiwan, which has a population of about 24 million. Hakka make up about four percent of the population of Hong Kong. In 1990 it was estimated that there were over 38 million Hakka in the People's Republic of China and the Hakka population accounts for approximately 3.7 percent of the total Chinese population. In 1992, the International Hakka Association placed the total Hakka population worldwide at approximately 75 million. Hakka are numbers in other countries are hard to estimate because censuses there when they are taken tend to lump all Chinese together, without distinguishing different groups like the Hakka, and sometimes don't count Chinese so accurately anyway. |~|

Hakka traditionally migrated to rugged, mountainous areas in south China and Taiwan, occupying land that other Chinese found too poor farming. This settlement pattern developed because the best land was occupied by other people at the time the Hakka migrants arrived. Most Hakka in China are concentrated in northeastern Guangdong, east of the North River, in the mountainous, less fertile region of Meizhou Prefecture. Meizhou, which includes the seven predominantly Hakka counties that surround Meixian, is considered the Hakka “heartland" and is claimed by many Hakka as their native place. The Hakka are well represented in southwestern Fujian, southern Jiangxi, eastern Guangxi, Hainan Island, Hong Kong and Taiwan. There are some in Sichuan and Hunan. The climate in the places Hakka live is hot in the summer and mild in the winter, with damaging winds, flooding, and typhoons occurring from time to time. Rice, tea, citrus fruits, and vegetables all grow well but winter frosts sometimes cause problems.

Early History of the Hakka

The ancient Hakka are believed to have originated from southern Shanxi, central Henan and Anhui provinces in north-central China. Shanxi and Henan provinces are regarded as the cradle of Chinese civilization and the homeland of all Han Chinese. The Hakka migrated from there to southern China in five major waves of migration that began around the A.D. 4th century and ended in the mid 18th century (See Below). The Hakka tended to take up residence in the mountains because the lowlands were already occupied.

The history of the Hakka is one migration and conflicts with the people they lived around and competed with for land. Because they had such a hard time establishing a homeland they made up many of the migrants who left China for Southeast Asia, the Americas and Europe. The Hakka people have traditionally lived in areas where the farming conditions are poor and inconvenient transportation links both isolated them and forced them to continually migrate into new lands. The isolated nature of their communities has traditionally limited their exchange and integration with other cultures, and as result of this many Hakka communities have preserved their traditional dialects, culture and customs. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

There were also frequent clashes. In Fujian and Taiwan the Hakka endured hostile relations with Min. In Guangdong they fought with Yue speakers. Hakka-Yue conflicts were particularly violent throughout the middle of the 19th century after the Taiping Rebellion, and during the Hakka-Bendi Wars (1854-1867). During this time “Hakka" had a negative meaning. Nicole Constable wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The worst insult, which was recounted by Yue to foreign missionaries, was the implication that the Hakka, with their strange language and unfamiliar dress and customs, were not in fact Chinese but were more closely related to other “barbarian" or “tribal" people. Such accusations infuriated the Hakka, who proudly sought to defend their identity and set the record straight. Since then, studies of Hakka history, based largely on genealogical evidence and other historical records, as well as linguistic evidence, support and substantiate Hakka claims to northern Chinese origins. In the People's Republic of China the Hakka are officially included in the category of Han Chinese. By the early twentieth century, following a period of ethnic mobilization, “Hakka" became more widely accepted as an ethnic label. |~|

Five Migrations of the Hakka

The Hakkas have taken shape through five great migrations. According to historical records the Hakka people had migrated southwards from the Central Plains of China to escape the turmoil of the Yongjia period (A.D. 304-312) and the wartime ravages of the late Tang dynasty and the Song dynasty. Many of the Hakka settled in Fujian and Guangdong Provinces. Historians agree these migrations took place but do not agree on the exact time and sequence of the earliest migrations. The name Hakka was first applied by the local people (bendi) in the fifth and and last migration. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences; [Source: Nicole Constable, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

1) The first migration of the Hakka occurred mostly in the A.D. 4th century. Some scholars say it began during the last years of the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25-220) and others say it lasted into the Jin Dynasty and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (A.D. 420 to 589), when a large number of people living in Central Plains crossed the Yellow River and the Yangtze River, and moved southward to avoid the chaos caused by wars with Mongol-like invaders from the north. Most historians place the first migration during the fourth century at the fall of the Western Jin dynasty, when Hakka ancestors reached as far south as Hubei, south Henan, and central Jiangxi.

2) The second migration of the Hakka occurred between the 9th and 10th centuries, when the Hakka reached south China (Fujian and Guangdong). This period is less debated.This migration occurred after the Huangchao peasants uprising in the late years of the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906). Ancestors of the Hakkas, again avoiding the war disasters, migrated to the southeastern Jiangxi Province and the western Fujian Province, some even entering faraway Guangdong Province.

3) The third migration of the Hakka took place at the end of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the Mongol hordes swept to the south and the Chinese emperor fled in panic to Fujian and Guangdong provinces. The Mongol invasion displaced people from Jiangxi and southwestern Fujian and forced them further into the northern and eastern part of Guangdong. This wave stretched from the beginning of the twelfth century to the middle of the seventeenth century. By the end of the Yuan dynasty (A.D. 1368), northern and eastern Guangdong were dominated by Hakka.

4) The fourth migration of the Hakka lasted from the mid-seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. It began with the Manchu conquest and continued during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), when the Hakkas' economy was prospering and their population expanded in Fujian, Jianxi and Guangdong provinces and they needed some place to go. A shortage farmland pushed the government into implementing an immigration policy that forced the Hakkas to migrate to the south and west, into the middle, eastern, western and coastal areas of Guangdong as well as Sichuan, Guangxi, Yunnan, Hunan, Taiwan, and southern Guizhou.

Hakka Couple in the Philippine Boxer Codex (1590)

5) The fifth and last major migration of the Hakka in China began in the 17th century but occurred mostly in the middle and late 19th century centuries, when conflicts between the Hakka and the Yue increased. Population pressure, the Hakka-Bendi (Yue) Wars, and the large Hakka involvement in the Taiping Rebellion pushed the Hakka in southeast China deeper into Fujian, Guangdong, Sichuan, and Guangxi provinces.

This migration was largely a consequence of Hakka populations in western Guangdong Province increasing sharply, leading to conflicts with indigenous populations. The Imperial Chinese government forced part of the Hakkas to move to the faraway places, in this case the mountainous areas in the western Guangdong Province, Leizhou peninsula, Hainan Island, and Guangxi Province. At this time more and more Hakkas started to go abroad and seek their fortune outside of China. ~

The five great migrations have distributed the Hakkas relatively broadly, but they have always managed to stick together in relative compact communities. This and the fact they have done well in business and have been resented by local populations has earned them the name “the Jews of Asia.” At present, there are approximately more than 280 Hakkas counties in 19 provinces and autonomous regions, with Guangdong, Jiangxi, and Fujian mostly centralized. The total Hakkas population is 58.1 million, including approximately 49.2 million in the mainland, 6.8 million in Taiwan, 2 million in Hong Kong, and 100 thousand in Macao.In addition, there are about five million Hakkas living the Southeast Asia. ~

Hakka Migrations Abroad

The last of the five migrations in China in the 19th century mentioned above sent Hakka emigrants in search of better lives farther afield. Waves of Hakka migrations from mainland China primarily to Taiwan and South East Asia. The colonization of South East Asia by European powers opened the region to Chinese immigrants, most of whom originated from southeastern coastal China, including Hakka regions in Fujian and Guangdong provinces. The hundreds of thousands of Hakka that migrated to what are now Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei, and Singapore worked as miners, laborers, and shop keepers. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Hakka also migrated in significant numbers in the 19th and early 20th centuries to the British colony of Jamaica and French-controlled Mauritius, as well as the United States, Canada, and parts of Latin America. The British hired many Hakka as civil servants because they were considered hardworking and trustworthy. By the mid 20th entury Hakka could be found on virtually every continent, from South and Southeast Asia and the Pacific to Europe, North and South America, Africa, and the Caribbean.

The Hakka first arrived in Taiwan in the 17th century during the Dutch occupation of the island. Migration to Taiwan continued until Japan took over the island in 1895. Hakka settled in the region that became Hong Kong as early as the 14th century. The influx of the Hakka continued and boosted the population in the 17th and 18th centuries, up to the mid-19th century. A few vestiges of their language, songs and folklore survive, most visibly in the wide-brimmed, black-fringed bamboo hats sported by Hakka women in the New Territories. Hakka was the language of the original inhabitants of Hong Kong. Only about a few tens of thousands still speak it, mostly old people.

Two international Hakka organizations, the Tsung Tsin (Congzheng) Association and the United Hakka Association (Kexi Datonghui) were organized by Hakka intellectuals and elite in the early 1920s in order to promote Hakka ethnic solidarity and foster a public understanding of Hakka culture. In 1921, over 1,000 delegates representing Hakka associations worldwide attended a conference in Canton to protest the Shanghai publication of The Geography of the World, which described the Hakka as non-Chinese. Today these international Hakka voluntary organizations have branches reaching from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore to the United States, Canada, and beyond. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

See Separate Article CHINESE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Later History of the Hakka

Hakka wedding in East Timor

During the nineteenth century, Hakka conflicts often grew into longterm violent feuds. Longer-lasting feuds between Hakka villages, between Hakka lineages, or between the Hakka and the Yue were often over land or property, theft, marriage agreements, or other personal conflicts. The theft of a water buffalo and a broken marriage agreement between a Yue man and a Hakka woman were contributing events that helped escalate Hakka-Yue conflicts into large-scale armed conflicts during the 1850s. Conflicts between Hakka Christian converts and non-Christian Chinese were also common during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

During the 19th century, Hakka peasants often had to supplement their agricultural work with other occupations. They worked as charcoal makers, blacksmiths, itinerant weavers, silver miners, dockworkers, barbers and stonecutters. As early as the Southern Song dynasty, Hakka men sought their fortunes by joining the military. The Taiping army, the Nationalist forces of Sun Yatsen, and the Communist army during the Long March were all comprised of large numbers of Hakka soldiers. [Source: Nicole Constable, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Despite their small numbers and economic disadvantages, the Hakka have long played an important role in Chinese politics and produced a number prominent leaders both on the mainland and outside China. During the Qing dynasty, the Hakka fared well in the imperial examinations and ascended into the imperial bureaucracy. In the 19th century many Hakka, including the movement’s leader, Hong Xiuquan, were at the forefront of utopian, anti-Qing Dynasty Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864). Hakka regions in Guangdong and Fujian province were fertile ground for Communist insurgents in the 1920s to 1940s. Among these were Deng Xiaoping, who later became the leader of the People's Republic of China. Several other leaders of the early revolutionary Communist Party were Hakkas. They occupied one-quarter of the seats in the first post-revolutionary politburo. Among other well-known Hakka political figures are Zhu De, the military commander during the Long March; Marshal Ye Jiangying, leader of the Peoples Liberation Army; and former Communist Party Secretary Hu Yaobang.

In Taiwan in the 1940s and 1950s, the Hakka were major players in the anti-Kuomintang resistance, and many Hakka were killed in the anti-Communist crackdown on that island. Among these were Lee Teng-hui, the late president of Taiwan. Other prominent Hakka include Lee Kuan Yew, the Singaporean strongman who founded Singapore was Hakka; So too is former Thailand prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra; Burma's Prime Minister Ne Win; and the governor-general of Trinidad and Tobago, Sir Solomon Hochoy. Some sources also assert that Dr. Sun Yatsen and the Soong siters was Hakka (See Famous Hakka below). [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 |~|]

Hakka are recognized in China and Taiwan as Han Chinese. An active ethnic movement in Taiwan promotes using the Hakka language in radio and television broadcasts and supports including Hakka in public affairs. Hakka are sometimes the target of economic and political discrimination. Periodic anti-Chinese riots in South East Asia have targeted Hakka communities, including deadly riots in Jakarta in 1998. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Hakka Language and Names

Hakka woman

Although the Hakka language was for a long time the primary unifying force behind the Hakka few people speak it anymore. It is regarded as a southern Chinese language even though many linguist regarded as more similar to Mandarin than Cantonese. Linguists say the Hakka language is closer to the ancient Chinese of the Yellow River area, considered the birthplace of Chinese civilization, than any other language spoken today. Today, the Hakka language is spoken so little it is in danger of dying out. [Source: Nicole Constable, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Unlike standard Mandarin Chinese, which has four spoken tones, Hakka has six tones. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The version of Hakka dialect spoken in Meixian area of Guangdong is considered the standard form and can be transcribed into standard Chinese characters as well as other Chinese vernaculars. Linguists classify Hakka as Southern Chinese along with Yue and Min (Hokkien) languages, signifying that these dialects developed from a variety of Chinese spoken in southern China between the first and third centuries a.d. Hakka, once classified by linguists as part of the Gan-Kejia Subgroup, is now considered a separate category.

Hakka is regarded as one of the eight major Chinese dialects. It developed from the ancient common language of the Han nationality of Central Plains — the Heluoya language —and later, in succession, incorporated elements of the Wu and Chu dialects as well as the ancient Yue, Jiangxi, Guangdong and Fujian dialects. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,”“Hakka family names (surnames) are transmitted through the father's line (patrilineally). Individuals have a personal name consisting of two syllables. When addressing someone, the surname is spoken first and the personal name follows. In families keeping a genealogy by generation, boys are often given a “generation" name as part of their personal names. The personal name can thus be used to identify the generation to which he belongs. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Hakka Religion

The Hakka do not have their own distinct religion, but like most other Chinese, traditionally practiced a blend of Daoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and “folk" religion, subject to regional variation. Hakka practice ancestor worship and believe that the spirits of their ancestors (zuxian) influence the lives of the living and thus required special care, offerings, and worship. They erected homes, located graves, and built ancestral halls according to the principles of feng shui. Hakka honor and appease the ancestors by lighting incense and offering sacrifices on ritual occasions. Outside of mainland China many Hakka are Christian, particularly in Taiwan. In Malaysian and Indonesia a sizable percentage are Muslim. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: In many communities, Hakka beliefs and practices closely resemble those of the Yue [Cantonese]; however, in other cases, anthropologists have also observed important differences. For example, during the nineteenth century the Hakka did not worship as many of the higher-level state-sanctioned gods or Buddhist deities, placed more weight on Daoist beliefs and ancestor worship, and were more likely to practice spirit possession than other Chinese in Guangdong. Some missionaries characterize the Hakka as having more “monotheistic tendencies" than other Chinese; these tendencies may have contributed to the fact that relatively larger numbers of the Hakka converted to Christianity during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than did other Han Chinese. In some parts of Hong Kong, the Hakka have fewer shrines and ancestral altars in their homes than the Cantonese. The same religious practitioners — Buddhist and Daoist priests, spirit mediums, feng shui experts, and various types of fortune-tellers — were observed among the Hakka during the nineteenth century as among the Yue. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Hakka Christian missionaries became particularly active in parts of Guangdong and Hong Kong. [Source: Nicole Constable, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Hakkas at a Christian school in 1921

Sanshan Guowang (“King of the Three Mountains" or “Three-Mountain-Guardian”) is one of the most important deities of the Hakka people in eastern Guangdong Province. He is worshipped in many Hakka village temples. According to legend, spirits inhabiting three mountains in the Hakka region of Guangdong became protectors and saved the people from disasters. People began worshipping these spirits and built temples in their honor. Some members of the She minority also worship this god. Many people think the Sanshan Guowang is a unique deity of Hakka people. Some Hakka worship the She hunting deity under the influence of the She. ++

Many Hakka observe fengshui (geomancy), the belief that natural forces can affect one's fortune and well being and is reflected in the way people orienting their houses, tombs and furniture. Hakka also employ the ideas of yin and yang to promote internal harmony and bring good health. Among the Hakka, Christian-or Buddhist-derived ideas of hell exist side by by side with beliefs about influential spirits of the dead and their occasional return to earth. One nineteenth-century Protestant missionary said the Hakka were not very familiar with the Buddhist karmic concept of one's life influencing rebirth or the Buddhist idea of hell with its tortures and purgatory. Instead, he asserted that the Hakka ascribed to the Daoist idea that “the righteous ascend to the stars and the wicked are destroyed". |~|

Hakka have traditionally practiced double burial. When a relative dies, a funeral is performed, and the deceased is buried in a temporary grave. After five to seven years, the corpse is exhumed, the skeleton is cleaned and purified, and carefully arranged in a large ceramic vessel. The vessel is then interred in a permanent site of then on the side of a hill in a place with good feng shui. In Taiwan it is not unusual to find clan burial sites climbing halfway up a small hill or see large family mausoleums containing the remains of many family members. These tombs are elaborately decorated and the site ancestor rites. ++

Hakka Holidays and Festivals

The Hakka have traditionally observed the most common Chinese life-cycle rituals and calendrical festivals, including the Spring Festival (Lunar New Year, Chinese New Year), the Lantern Festival, Qingming (Tomb Sweeping Day), the Mid-Autumn Festival, the Dragon Boat Festival, Chong Yang, and Winter Solstice. The Hakka generally do not observe Yu Lan (“Hungry Ghost") Festival which is popular among other Chinese. [Source: Nicole Constable, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

The Spring Festival (usually in late January or February according to the Western calendar) is the most important holiday for the Hakka. As is true with other Chinese, Hakka try return to their hometowns and villages and work stops and most everything is closed for three or more days. Houses are thoroughly cleaned; rhyming couplets with lucky phrases are placed on doorways; and families eat an elaborate meal with many traditional dishes on New Year's Eve. New Year's Day is spent visiting other relatives and paying respects to seniors. Traditional children received new clothes for the coming year but now they often receive money. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Qingming in April is honors ancestors in the father's line. People prepare sacrificial foods (rice, meats, sweet rolls, and wine) and visit the family tombs and tidy them up. The spirits of the ancestors are invited to feast on the food, Firecrackers are set off. This ceremony firms up the bond between the living and deceased ancestors. ++

Famous Hakka

Hakkas are renowned as artists and known for surviving under great difficulties, doing pioneering work in the remote places, being resourceful and enterprising, arduously struggling and valuing education. They have distinguished themselves throughout Chinese history with their outstanding abilities and achievements in a number of fields and had great success in business. Wealthy Hakka have amassed large fortunes and have a substantial amount of power which has bred some resentment against Hakka by the non-Chinese and non-Hakka Chinese.

Famous Hakka include: 1) Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China; 2) Soong Ching-ling, wife of Sun Yat-sen, 3) the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, 4) Singaporean leader Lee Kuan Yew, 5) Soong May-ling (Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Ching-ling’s sister, and one of the Soong sisters); 6) Thaksin Shinawatra, former Thailand prime minister; his sister 7) Yingluck Shinawatra, also a former Thailand prime minister; 8) T. V. Soong, founder of the Bank of China; 9) Aw Boon Aw, who made his fortune selling Tiger Balm. .

Other Famous Hakkas have included: 1) the well-known prime minister Zhang Jiuling in the Tang Dynasty; 2) the renowned Neo-confucianist Zhu Xi in the Song Dynasty; 3) the national hero Wen Tianxiang in the Southern Song Dynasty; 4) the patriotic military officer Yuan Chonghuan in the Ming Dynasty; 5) the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom leader Hong Xiuchuan; 6) the great national democratic revolution leader Sun Yat-Sen; 7) the revolutionary martyr Liao Zhongkai; 8) the great proletariat revolutionists, statesman, and strategist Commander-in-Chief Zhu De and marshal Ye Jianyin; 9) vice-chairmen of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress Zhang Dingcheng, Liao Chengzhi, Chen Pixian; 10) the renowned military officers Zhang Fa Kui, Ye Ting, Liu Yalou, Xiao Hua, Xue Yue, Yang Chengwu; 11) the historian and poet Guo Moruo; 12) the chemist Lu Jiaxi; 13) the mathematician Qiu Chengtong; and 14-20) the industrialists Zhang Bishi, Zhang Rongxuan, Zhang Yaoxuan, Hu Wenhu, Tian Jiabing, Zeng Xianzi.

Well known Hakka artists and figures in the entertainment world include Hong Kong actors Chow Yun-Fat and Leslie Cheung, Hong Kong actress Cherie Chung, Taiwanese film director Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Hong Kong singers Deanie Ip and Leon Lai,, Hong Kong actor and musician Jordan Chan, Hong Kong actor and director Eric Tsang, Taiwanese singer Cyndi Wang,Malaysian pop stars Penny Tai and Eric Moo, and Singaporean actress and singer Fann Wong. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Chinese government

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org |

Last updated October 2022