REINDEER AND CARIBOU BEHAVIOR

Reindeer and caribou are the same species (Rangifer tarandus). The main difference between the two is that reindeer are domesticated or semi-domesticated and found in Scandinavia, Siberia, northern China and Mongolia and caribou are wild and found in North America. Caribou are very tame and relatively easy for people to approach. It is not uncommon for tourists to approach a caribou within ten meters, something a deer would never let them do. This is probably one reason why reindeer have been relatively easy to domesticate and hunt. Some scientist attribute their tameness to curiosity.

Caribou and reindeer are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Caribou sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They have a keen sense of smell, which allows them to find food buried deep under snow. Caribou are good swimmers and can run fast, reaching speeds of 80 kilometers per hour. They have pretty good endurance too, maintaining a fast trot for long periods of time. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Caribou are gregarious. They form the largest groups, which can number in the tens of thousands, during the summer months. It is believed they do this in part to bring some relief from mosquitoes, warble flies, and nose bot flies that attack and harass them. As the weather becomes cooler groups become smaller but caribou may aggregate again during the rut and fall migration. During the mating season bulls spar with competitors to keep them from breeding with females in their area. Most encounters are brief, but serious battles do occur which can result in injury or death. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Most caribou winter in forested areas, where snow conditions are more favorable. Caribou are able to locate forage under snow, apparently by their ability to smell it. To reach the forage they use their front paws to dig craters. Dominant caribou frequently usurp craters dug by subordinate animals.

Reindeer are meek by nature. They never kick or bite people and are relatively easy to raise. They are usually raised by women. It is not necessary to enclose them with a fence, or feed them. You can just put them out to graze. They leave the campsites when night comes, gathering in herds and grazing in the forests, and come back at dawn. They don't leave in the daytime. The reindeer are good at finding food. Even in the winter, when the mountain paths are sealed by snow, they can also use the broad forepaws to dig up into the snow, as deep as one meter, to look for mosses to eat. Reindeer like salt. Their masters can knock on the salt box if they want to use the reindeer. They will follow the sound and come. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

REINDEER AND CARIBOU: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

DEER (CERVIDS): CHARACTERISTICS, ANTLERS, HISTORY, ECOSYSTEM ROLE, HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

DEER (CERVID) BEHAVIOR, FEEDING AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ROE DEER: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SIKA DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MUSK DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PERFUME, MEDICINE, FARMS factsanddetails.com ;

DEER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

RED DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ELK: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK): CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HABITAT, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS, DRUNKENESS factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) AND HUMANS: ATTACKS, RAMPAGES, CAR CRASH TESTS factsanddetails.com

Caribou Mating and Reproduction

Caribou are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding. They breed once a year usually in October and early November. The number of offspring can be as high as two but typically is one. The average gestation period is 7.6 months.

Males compete for access to females during the fall rut (mating season). In late August and September, prime bulls shed the velvet that surrounds their antlers. Sparring begins shortly there after. Females can be sexually mature as early as 16 months of age but more commonly at 28 months. With good nutrition females give birth to calves each year, but may skip years in poor ranges.

Dominant males restrict access to small groups of five to 15 females. Males stop feeding during this time and lose much of their body reserves and may engage in battles with one another which involves clashing and locking antlers. Sometimes bulls become so preoccupied with fighting, courting and mating they lose one fourth of their weight, and become injured and exhausted. making them vulernable to attacks by predators. Dominant males usually mate with several females. They mount from behind like horses and elephant and most mammals do. Young bulls sometimes attend senior bulls like proteges and a mentor.

Among most deer, normally-placid bucks become fierce warriors during the rutting. Their eyes become bloodshot, their necks puff out and they charge any threat with antlers down. Battling bucks run head on into one another with their antlers and keep charging until one backs off. Sometimes two bucks become locked up and die together.

Caribou Offspring and Parenting

Young caribou are relatively well-developed when born but weak and vulnerable to predators. Pre-weaning provisioning and protecting are done by females. Males are not involved in the raising of offspring beyond their participation in herds. The average weaning age is 1.5 months. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity as early as 16 months; males do so at 28 months.

Typically a single calf, weighing three to 12 kilograms, is born in May or June. Twinning has been reported, but is very rare. Newborn calves can stand up minutes after birth and are able to suckle and follow their mother after an hour. Within 24 hours their legs are strong enough to run and they are capable of outrunning a human. After a week they can keep up with their mothers. After three weeks they can outrun a bear. Reindeer calves are vulnerable to attacks from bears, wolves and golden eagles. It is necessary for them to develop quickly to escape predators, namely wolves.

Calves nurse exclusively for their first month, after which they begin to graze. They continue to nurse occasionally through early fall, when they become independent. After nursing a calf through the summers females are often extremely thin. The suckling period rarely last past the first week of July. Calves rely mainly on foraging for nutrition after 45 days old. Although weaned by early autumn, calves stays by their mother's side through the winter to help dig up lichen.

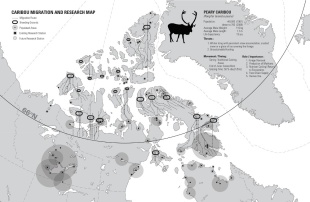

Caribou Migrations

Caribou travel greater distances than any other terrestrial mammal, traversing more than 5,000 kilometers in a year during their extensive migrations in spring and fall. Spring migration take caribou from their winter range back to their calving grounds. Use of traditional calving grounds is the basis by which caribou herds are defined. Domesticated reindeer spend most of their time roaming free and foraging for food. They and their human herders follow routes that are not all that different from routes they would follow if they were wild.. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Caribou follow age-old migration routes across rivers and around mountains to calving grounds and grazing areas. They march through deep snow, swampy bogs and spongy tundra and often swim through ice cold water. In Alaska, a single herd of 600,000 caribou makes an annual migration following ancient paths that have been used by hundreds of generations. Some of the trails are 10 to 20 centimeters deep and filled with caribous dung and bones of caribou scattered here and there.

Caribou in northern Canada and Alaska migrate between their birthing grounds around Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and feeding areas in the Yukon and Northwestern territories. Their numbers declined from 178,000 in 1989 to 130,000 in 2001. Some scientists said that climate change was a likely reason because it caused spring greening to start ands end earlier and vegetarian may die back before calves gain enough weight to survive the winter. [Source: National Geographic]

Why and How Caribou Migrate

Reindeer spend the winter at lowland tundra feeding grounds rich in lichens. During the spring they head for the calving (fawning) grounds on the flowering tundra. During the summer they escape from clouds of mosquitos and hordes of biting black flies in the lowlands and head for feeding grounds in the highlands and forests that are rich in grasses and other vegetation.

David Attenborough wrote : “Dietary inadequacies, coupled with seasonal changes in weather cause major problems to caribou. During the summer, the caribou of northwest Canada and Alaska, not far from the continent’s northern coast, feed on a wide variety of broad-leaved plants including cotton grass and low dwarf willow. Here the females give birth. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

But when the weather gets even colder with the coming of autumn, many of these plants shed their leaves. Even those that keep their leaves become buried beneath the snow. The caribou can no longer stay out in the open tundra and they start in a long journey southwards to areas where patches of coniferous forest offer some shelter from the biting winds and blizzards. The journey is several hundred miles long and may take weeks. The animals move slowly, around two miles an hour, and often in single file feeding when they can and traveling both day and night, How far they move in twenty-four hours varies according to snow conditions. Sometimes it may be as much as thirty miles, sometimes only a tenth of that distance.

They follow regular pathways , but blizzards and deep snow drifts may here and there compel them to vary their route. But at length, they reach their winter feeding grounds. Here they will stay for several months. The food, however, is poor, consisting largely of a kind of lichen, known inaccurately as reindeer 'moss', that grows over the rocks.

Caribou and Reindeer— Undisputed Migration Champs

The claim that caribou have the longest land migration of any mammal relied on a single study so in the late 2010s scientists decided it was time to take another look at the claim, and published their results in October 2019 in Scientific Reports. “Caribou have “long been credited with the world’s longest migration,” Kyle Joly, a caribou expert and wildlife biologist with the National Park Service, but the claim really hadn’t been validated very robustly.”

Cara Giaimo wrote in New York Times,“He decided it was time to double check — and to “see if there’s another animal out there that might take the crown,” he said. He and his collaborators started asking around for data sets, and amassed dozens from across the globe. They measured each distance as the crow flies, from where the animals started to where they ended up, and then back again. “The top finishers illustrate common drivers behind migration, as well as contemporary threats to these storied pilgrimages.[Source:Cara Giaimo, New York Times, November 13, 2019]

1) Caribou: For the moment, caribou stayed on top. In fact, if you were to rank by groups of animals, rather than species, populations of caribou would take all five top spots. The Bathurst Herd, from the Northwest Territories, and the Porcupine Herd, from Alaska and the Yukon Territory, are the elites of the elites — each has been tracked traveling about 1,352 kilometers (840 miles). That’s like walking from Washington, D.C. to Tallahassee, Fla. Dr. Joly, who spends a lot of time watching pings from caribou GPS collars moving across a digital map, was pleased, but not too surprised. “I was fairly confident,” he said.

“2) Reindeer: The runners-up among the list of long-haulers are a herd of reindeer from the Taimyr Peninsula in Russia, which traveled nearly 1,207 kilometers (750 miles) per year. They may not hold this place for long. In recent years, swarms of mosquitoes, incubated by warming temperatures, have driven many of the reindeer away from their regular route. The population has also been decimated by poaching.

Other animals with annual long-haul migrations include blue wildebeest (600-700 kilometers round trip in east Africa), Mongolian gazelles and Tibetan antelopes (chiru). A group of gray wolves in Canada, believed to follow caribou, was the only other tracked species that migrated over 1,000 kilometers in a year. A single gray wolf in Mongolia even traveled 7,247 km in a year.

Reindeer and Caribou Lifespan, Predators and Mosquitoes

Females caribou generally have longer life spans than males, some over 15 years. Bulls are highly susceptible to predation after the rut, which can leave them injured and/or exhausted. Bulls typically live less than 10 years in the wild. Their average lifespan for caribou in the wild is 4.5 to 15 years. Their average lifespan in captivity is 20.2 years. The average lifespan of males in the wild is 8 years. The average lifespan of females in the wild is 10 years. After the population of reindeer on an uninhabited island off of Alaska crashed from 6,000 to 42 as a result of overgrazing only one of the survivors was a male. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Caribou have to deal with predators such as wolves and huge clouds of insects. Caribou are important prey species for large predators, such as brown bears and particularly gray wolves, especially during the calving season. Calves are highly vulnerable to during their first week of life. Healthy adult caribou are less susceptible to predation until old age and illness weakens them. By traveling in herds, caribou increase the number of individuals that can watch for predators. |=|

Caribou calving grounds are usually in areas with high visibility. Reindeer calves only have a 50-50 chance of survival. They are vulnerable to predators such as foxes, wolverines, lynxes and eagles, not to mention disease and bad weather. Mature reindeer are sometimes victimized by brain worms or a layer of ice underneath the snow that prevents them from eating lichens which nourish them during the winter. An estimated 10,000 reindeer died in the Chukchi peninsula in northeast in December, 1996 after a period of warm weather and heavy rains was followed by -40 degrees F temperature that produced a layer of ice over grazing lands that made impossible for the animals to feed.

Reindeer are tormented by mosquitos. They are particularly vulnerable when they shed their winter coats. Sometimes mosquitos swarm around a calf and draw so much blood the young animal weakens and dies. Reindeer are plagued by more than 20 different parasites including warbles flies and tongue worms. Stampedes sometimes occur when herds are attacked by swarms of mosquitos and biting flies.

Wolf Attack of a Caribou

Wolves are the main natural predators of reindeer and caribou. Describing an unsuccessful attack by a wolf on a herd of caribou, Arctic researcher David Mech wrote in National Geographic,"The herd, sensing the wolf, was drown together as is by some giant biological magnet. The tightly pressed group flowed quickly forward...The white wolf made its decision. Instantly it sprang forward. While stragglers gravitated toward the herd, the wolf began closing the 200-yard gap." [Source: David Mech, National Geographic, October 1977]

"As the wolf pressed close, the caribous increased their speed. Straight toward them the white wolf sped, with legs alternately stretching out then pulling together in 15-foot bounds...The chase covered a quarter of a mile, and the wolf tried its best. Still the hunter was unable to come closer than about 200 feet of its intended prey...Less than a minute after the chase had begun, it was over."

Historically wolves have fed on the weak, old and infirm and the conventional wisdom was that this helped the reindeer population by ensuring the strongest produced offspring and the herd as whole didn't overglaze the land. With most of the wolves in Scandinavia now gone the primary controlling agent of the reindeer herds are the Lapps.

It is somewhat of a myth that the health of deer populations depend on wolves to cull weak and diseased animals. Studies show that the size and health of deer population is related to snow depth, cold and the availability of food, not wolves. One biologist told National Geographic, "Our data shows that wolves take mainly the youngest deer—those less than a year of age. Old, weak animals are the second most common targets...The herds can handle it" because deer reproduce a lot.

Caribou Herding Behavior — Same Principal as Schooling Fish?

Peter Miller wrote in National Geographic: In nature animals travel in large numbers. That's because, as members of a big group, whether it's a flock, school, or herd, individuals increase their chances of detecting predators, finding food, locating a mate, or following a migration route. For these animals, coordinating their movements with one another can be a matter of life or death. [Source: Peter Miller, National Geographicm July 2007]

"It's much harder for a predator to avoid being spotted by a thousand fish than it is to avoid being spotted by one," says Daniel Grünbaum, a biologist at the University of Washington. "News that a predator is approaching spreads quickly through a school because fish sense from their neighbors that something's going on.” Why do animals often travel in large groups? When a predator strikes a school of fish, the group is capable of scattering in patterns that make it almost impossible to track any individual. It might explode in a flash, create a kind of moving bubble around the predator, or fracture into multiple blobs, before coming back together and swimming away.

Animals on land do much the same, as Karsten Heuer, a wildlife biologist, observed in 2003, when he and his wife, Leanne Allison, followed the vast Porcupine caribou herd (Rangifer tarandus granti) for five months. Traveling more than a thousand miles (1,600 kilometers) with the animals, they documented the migration from winter range in Canada's northern Yukon Territory to calving grounds in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. "It's difficult to describe in words, but when the herd was on the move it looked very much like a cloud shadow passing over the landscape, or a mass of dominoes toppling over at the same time and changing direction," Karsten says. "It was as though every animal knew what its neighbor was going to do, and the neighbor beside that and beside that. There was no anticipation or reaction. No cause and effect. It just was.” Briefly describe the migration of caribou.

One day, as the herd funneled through a gully at the tree line, Karsten and Leanne spotted a wolf creeping up. The herd responded with a classic swarm defense. "As soon as the wolf got within a certain distance of the caribou, the herd's alertness just skyrocketed," Karsten says. "Now there was no movement. Every animal just stopped, completely vigilant and watching." A hundred yards (90 meters) closer, and the wolf crossed another threshold. "The nearest caribou turned and ran, and that response moved like a wave through the entire herd until they were all running. Reaction times shifted into another realm. Animals closest to the wolf at the back end of the herd looked like a blanket unraveling and tattering, which, from the wolf’s perspective, must have been extremely confusing." The wolf chased one caribou after another, losing ground with each change of target. In the end, the herd escaped over the ridge, and the wolf was left panting and gulping snow.

How did the caribou evade the wolf? For each caribou, the stakes couldn't have been higher, yet the herd's evasive maneuvers displayed not panic but precision. (Imagine the chaos if a hungry wolf were released into a crowd of people.) Every caribou knew when it was time to run and in which direction to go, even if it didn't know exactly why. No leader was responsible for coordinating the rest of the herd. Instead each animal was following simple rules evolved over thousands of years of wolf attacks. That's the wonderful appeal of swarm intelligence. Whether we're talking about ants, bees, pigeons, or caribou, the ingredients of smart group behavior — decentralized control, response to local cues, simple rules of thumb — add up to a shrewd strategy to cope with complexity.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025