REINDEER AND CARIBOU

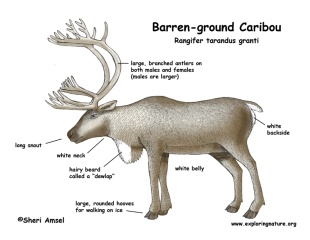

Reindeer and caribou are the same species (Rangifer tarandus). The main difference between the two is that reindeer are domesticated or semi-domesticated and found in Scandinavia, Siberia, northern China and Mongolia and caribou are wild and found in North America. Male and female caribou and reindeer have antlers, making them unique among deer. There are two main kinds of caribou: woodland caribou and barren ground caribou (which are about a third smaller than woodlands caribou). Mountain reindeer are found in some mountain ranges of Russia and northern Europe. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perenial Library, Harper and Row, "Nomads" 99-108]

Caribou are muskoxen and two large animals that lived in Ice Age terrain during the Ice Age and are still gooing strong today. They were adapted to the harsh, frozen tundra environments that characterized the Ice Age and live alongside other Ice Age megafauna such as the woolly mammoths and wooly rhinoceros that died out.

Reindeer can be wild, semi-domesticated, or domesticated, meaning they have been selectively bred with a specific purpose in mind. Reindeer are slightly smaller than caribou, with a slightly narrower body, especially when compared to their antlers, which can be large and heavy. Male reindeer and caribou are called bulls (or stags in some places). Females are called cows and youngsters, calves. Males often have whites clumps of hair that hang from their throats.

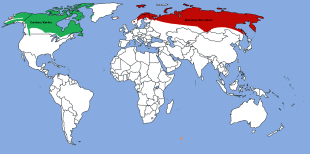

Caribou Habitat and Where They Live

Caribou have a nearly circumpolar distribution and inhabit Arctic tundra and subArctic (boreal) forest region in tundra, taiga and forests. The woodland subspecies of caribou (Caribou caribou) can be found as far south as 46̊ north latitude, while other subspecies — Peary caribou (R. t. pearyi) and Svalbard reindeer (R. t. platyrhynchus) — can be found as far north as 80̊ north latitude. Caribou and reindeer live primarily in the Arctic tundra, where the temperature average 23 degrees F throughout the year and can drop as low -76 degrees F. They are thought to have originated in North America. Up until 12,000 years ago they shared the Arctic tundra with wooly mammoths and mastodons.

Caribou and reindeer are the world's most widely distributed large land animals. As of the 1990s there were four million wild caribous in 200 herds: 102 in North America, 55 in Europe, 24 in Asia and 3 introduced herds on South Georgia Island in the southern Atlantic. Three fourths of these animals occur in just nine herds (eight in North America and one in Russia). In Alaska, there is a single herd with 600,000 caribou. Caribou are known for their long-distance migrations.

Woodlands caribou were once found as far south as Germany, Great Britain, Poland, and Minnesota and Maine in the U.S. but over-hunting and habitat degradation have reduced their historic range of caribou. Attempts to reintroduce them to these places have been thwarted in some places by a snail-bourne meningeal worm carried by white tail deer, who roam all over the United States. This parasite is relatively harmless to them but eats at the brain of caribou, moose, elk and other kinds of deer.

RELATED ARTICLES:

REINDEER AND CARIBOU BEHAVIOR: MIGRATIONS, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

DEER (CERVIDS): CHARACTERISTICS, ANTLERS, HISTORY, ECOSYSTEM ROLE, HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

DEER (CERVID) BEHAVIOR, FEEDING AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ROE DEER: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SIKA DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MUSK DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PERFUME, MEDICINE, FARMS factsanddetails.com ;

DEER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

RED DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ELK: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK): CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HABITAT, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS, DRUNKENESS factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) AND HUMANS: ATTACKS, RAMPAGES, CAR CRASH TESTS factsanddetails.com

Deer Family

Reindeer are members of the 60-member deer family, which includes elk. The largest deer are moose, which can weigh nearly a ton, and the smallest is the Chilean pudu, which is not much larger than a rabbit. Deer belong to the family “Cervidae”, which is part of the order “Artiodactyla” (even-toed hoofed mammals). “Cervidae” are similar to “Bovidae” (cattle, antelopes, sheep and goat) in that they chew the cud but differ in that have solid horns that are shed periodically (“Bovidae” have hollow ones).

Deer have a lifespan of around 10 years. A male deer is called a buck or stag. A female is called a doe. Young are called fawns. A group is called a herd. Deer don't hibernate and sometimes group together to stay warm. Particularly cold winters sometimes kill deer outright, mainly by robbing them of food, especially when a hard layer of ice and snow keeps them from getting at food.

The top speed of a deer is around 30 miles per hour. Some deer can reach speeds of 40mph for short bursts and gallop for three or four hours at a speed of 25mph. Some deer can vertically jump 25 feet. The tracks of stags are bigger and broader than those of does. They have a more swaggering walk.

Deer are hunted by humans and are prey of large carnivores such as tigers, cougars, wolves and occasionally bears. Deer meat is called venison. People have made buckskin jackets, moccasins and other items of clothing from deer hide. Reindeer outer fur is coarse and bulky. It traps air that keeps the warm. Garments made with reindeer fur keep people warm in the same way.

See Separate Article DEER factsanddetails.com

Reindeer Characteristics and Size

Reindeer and caribou are larger than most deers, including white tailed deer found in the U.S., and smaller than elks and have heavier bodies and shorter and thicker legs in relation to their body compared to deer. Reindeer reach full size at about four or five years of age. A large male weighs around 140 kilograms (307 pounds) and stand around 1½ meters (5 feet) at the shoulder. The largest caribou weigh up to 250 kilograms (550 pounds).

Caribou range in weight from 55 to 318 kilograms (121 to 700 pounds) and range in length from 1.5 to 2.3 meters (5 to 7.5 feet). They can have shoulder heights of up to 1.2 meters (4 feet). The various subspecies of caribou display a wide range of size. Generally though, those inhabiting more southerly latitudes are larger than those further north. The smallest caribou are generally found in the harshest habitats. The average basal metabolic rate of caribou is 119.66 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Ornamentation is different. Males of some subspecies are twice as large as females. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Reindeer are covered with mottled gray, brown and white fur. Their fur is generally grayish brown on their backs and white on their undersides. Their muzzle is hairy, broad and cowlike. The coat of the caribou is an excellent, lightweight insulation against the extreme cold temperatures they face. The hairs are hollow and taper sharply which helps trap heat close to the body and also makes them more buoyant. Color varies by subspecies, region, sex, and season from the very dark browns of woodland caribou bulls in summer to nearly white in Greenland (R. t. groenlandicus) and high Arctic caribou. White areas are often present on the belly, neck, and above the hooves.

Reindeer can sleep comfortably in temperatures as low as -45 degrees C and survive temperatures as low as -58 degrees F. Keeping them warm is a five centimeter-thick coat of fur with 13,000 hairs per square inch. During the summer they shed their fur and look moth-eaten. Molting reindeer drop so much fur they look like swamp trees with dangling moss.

Deer, cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread.

See Ruminants Under MAMMALS factsanddetails.com

Reindeer Legs and Hooves

A reindeer can reach speeds of 50mph (compared to 70 mph for a cheetah and 27.9 mph for the world's fastest human) for short bursts and cruise for long periods of time at 25 mph. Reindeer have an high-stepping gait when they run. The can outrun bears and wolves. Caribou and reindeer are also good swimmers. They have been seen swimming in the open sea in 20 foot waves and through rapids in spring-swollen rivers.

The hooves of caribou are large and concave, which support them in snow and soft tundra, conditions that they often face. The broad hooves are also useful when swimming. When they move, caribou make a unique clicking noise that is caused by the slipping of their tendons over the their ankle bones.

Reindeer have splayed hooves with unique dew claws (appendages that extend out like legs on a tripod) that not only enable reindeer to travel swiftly across the top of deep, soft snow they also are good for digging up lichen under a thick snow cover. The hooves are cleft like a deer's but leave an imprint that is round like a cow's. In the center of the hoof is a spongy pad that expands in the summer and shrinks in the winter and is covered with insulating hair.

Reindeer Antlers

Caribou are he only species of deer in which both sexes have antlers. Mature bulls can carry enormous and complex antlers, whereas cows and young animals generally have smaller and simpler ones. The antlers are covered with velvet that provide nourishment for growing antlers. Reindeer antlers feel soft. The racks of large males can reach a meter and a half in length. Every year in September reindeer lose their antlers, but before they do rub the velvet off against trees, revealing red antlers, colored by the animals blood.

Many deer annually grow new antlers in the spring and shed their old ones in the fall. Reindeer loose their antlers for four months in the autumn and the winter as a result of sex hormones that cause bone at the base of the antler to be reabsorbed. Mature bulls usually shed their antlers shortly after the rut whereas cows can keep theirs until spring. In the spring the animals grow a new pair of velvet-covered antlers. Only reindeer that have been castrated keep their antlers through the winter.

Female reindeer are not adverse to using their antlers against males when competing for scarce lichen patches in the wintertime. The "velvet" (soft skin laced with blood vessels and covered with fine hair) on the antlers provides the antlers with calcium and other nutrients from the body. The antlers reach full growth and peak hardness in the early fall. After this the blood supply to the velvet is cut off. The velvet is rubbed off on bushes and trees in August after the summer.

Among deer, antlers are a kind of symbol of strength and virility intended to impress females and intimidate rivals. They are used by males to battle one another in the rutting (mating season). After the rutting season is over in the fall, the antlers fall off. Males usually grow spike like antlers when they are two and develop a full rack when they are full grown are age six.

Reindeer and Caribou Food and Eating Behavior

Caribou are primarily grazing herbivores (eat plants or plants parts). Their diet is most variable during the summer, when they consume the leaves of willows and birches, mushrooms, cotton grass, sedges and numerous other ground dwelling species of vegetation. Lichens are an important component of the diet, especially in winter, but are not eaten exclusively. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Most of their summertime diet consists of grasses, sedges (protein-rich plants), leaves and woody plants that grow rapidly in the brief Arctic summer. During winter about 60 percent of a reindeer's diet is made up of lichens. Lichens are a high-energy food, which are 90 percent carbohydrates, but even so a reindeer has to consume eight kilograms of lichens a day to maintains it body weight. Fish are often fed to domesticated reindeer, which have a fondness for dried fish.

Caribou and reindeer spend most of their time grazing. They often snort and cough a lot because their nasal passages are filled with a fist-size ball of maggots. Reindeer eat a lot in the late summer to build up enough body fat to last the winter and fatten up at an astonishing rate in a short time. Reindeer can store food and go long period without food but still they have their limits. During the wintertime reindeer spend about ten hours a day foraging for lichen. They can smell the lichens under the snow. They dig and paw away at the snow with their hooves to reach the lichens. Reindeer normally forage through soft snow. Reindeer begin starving when ice or hard snow covers the lichens they can’t break through the ice with their hooves.

A common food consumed by caribou and reindeer in winter is a kind of lichen, known inaccurately as reindeer 'moss', that grows on rocks. David Attenborough wrote: To reach it, the caribou may have to sweep aside snow, which they do with their antlers. These have a branch close to their base which projects forward and serves as a shovel. For this reason, females as well as males develop antlers, unlike any other member of the deer family. But the lichen on which they feed, like the grasses of the Masai Mara, are poor in certain minerals. These are essential for the females if they are to produce milk for their young, so even before the warming spring sun has melted the ground, the herd starts to travel north again. The round trip is about a thousand miles long. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

Through their foraging activities, caribou can have a dramatic impact on communities of vegetation throughout their range. A single reindeer can consume up to 12 kilograms of lichens a day. Lichens take as long as 30 years to grow back after they have been consumed and scientists estimate that each reindeer needs at least 25 acres of lichen pasture to ensure survival. This is one reason why reindeer and caribou migrate. Reindeer depend on old growth forests and stable tundra conditions to produce lichens.

Caribou and Reindeer Conservation

Caribou and reindeer are not endangered. There are large herds of them — both wild and domestic — in Eurasia, Canada, Alaska, and few places in the lower 48 states including Michigan. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. On the US Federal List they are categorized as Endangered.. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. [Source: Kyle C. Joly and Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Alaska is home to more than 30 herds and in the the not too distant past had nearly double the number of caribou (1,000,000) than people. Caribou in the contiguous U.S. are considered endangered. Caribou in Alaska are of the barren-ground subspecies. Those found Washington and Idaho are of the woodland subspecies. The Selkirk Herd, inhabiting Washington, Idaho and southern British Columbia numbered only around 30 members in the 2000s.

Loss of habitat, overhunting, and other factors has contributed to the endangered status of woodland caribou in the US. Worldwide, the caribou population is estimated to be around five million. The largest herds now occur in Alaska, Canada, and Russia. Humans have heavily hunted the. In some places, particularly Russia, so many are taken by wolves that wolves have to be culled. Reindeer have been extinct in most parts of Europe since at least the 1600s. Exploration for oil and minerals in Russia and Canada has disrupted some migration routes High Arctic caribou populations are less vulnerable than woodland ones.

Reindeer and Their Numbers Getting Smaller Due to Climate Change?

In 2018, Euronews reported: Reindeer herders in Finnish Lapland are concerned their prized animals are getting smaller because of climate change. Finland’s reindeer population reaches 200,000 in the wintertime with around 1,500 herders relying on them for their livelihood, breeding them for meat, milk and fur. They are also a major tourist attraction with 300,000 people visiting the area annually for sleigh rides. [Source: Euronews, Associated Press, December 25, 2018]

But climate change in the region — mean temperatures in Lapland have increased by 1.5 degrees Celsius over the past 150 years — make it harder for reindeer to graze on their food as warmer winters mean more rain. “The worst is for us now, when we have the snow cover the ground, if we get rain coming on the snow, it means that the reindeer food, it’s going to be in the icebox,” Matti Sarkela, head of office for the Reindeer Herders’ Association told the Associated Press. “Reindeer can’t dig the lichen from the ground through the ice. That’s the worst thing (that) could happen for us during the wintertime of the climate change,” she added.

Stephanie Lefrere, a researcher from the Finnish Environment Institute concurred. “Reindeers are quite resilient,” she said, “what we have observed since (the) Ice Age, for instance, is that they can adapt to very drastic conditions. “But now the changes are too rapid and there are too many things,” Lefrere highlighted.

Research conducted over 20 years on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago found that although reindeer numbers had doubled, their size and weight had decreased — mostly due to greater competition for food. The survey, released in 2016 by the James Hutton Institute, found that adult reindeers born in 1994 weighed 55 kilograms while those born in 2012, weighed 48 kilograms. Meanwhile, the number of caribous or wild reindeer in the Arctic region has decreased by more than 50 percent since the mid-1980s, according to a report released earlier this month by the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. The study found that “climate indicators accounted for 54 percent of the variability in vital rates.”

Reindeer Deaths — Climate-Change-Induced Starvation and Chased Over a Cliff by a Lynx

In March 2005, 140 reindeer plunged to their death in Lappland in northern Sweden, possibly having been chased off a cliff by a single lynx, reindeer herders said. “It’s a massacre. I have never seen anything like this,” town spokesperson Nils Petter Pavval told local paper Norrlaendska Socialdemokraten, adding that the reindeer had been grazing when something frightened them. “It was a lynx that chased and frightened the reindeer off the cliff. Reindeer have a sixth sense, they know the cliffs and overhangs and thin ices. They don’t just rush off a cliff of their own free will, but must have done this in panic when a predator hunted them,” he added.According to Labba, the reindeer had been valued at about 300 000 kronor (R264 000). [Source: AFP, April 19, 2005]

In April 2019, scientists discovered the remains of more than 200 reindeer, which appear to have starved to death, on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago that sits between the mainland and the North Pole. Brigit Katz wrote in Smithsonian.com: Scientists believe that climate change is the culprit. The Arctic has been particularly hard hit by climate change, warming at almost twice the rate of the global average. Svalbard offers a particularly alarming example of this phenomenon; it is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet, Jonathan Watts reported for the Guardian. [Source: Brigit Katz, Smithsonian.com, July 31, 2019]

Higher temperatures mean more rain has been falling on the archipelago. In December 2018, the region experienced a heavy bout of precipitation that froze when it hit the ground, forming thick layers of ice on the tundra. During the colder months, Svalbard reindeer typically use their hooves to dig through the snow to reach the vegetation below. But this year, they couldn’t break through the ice that covered their food source. In the nearly 40 years that scientists have been monitoring the Svalbard reindeer, they have seen comparable death tolls only once before, after the 2007-2008 winter, according to the Agence France-Presse.

Scores of dead reindeer were not the only sign that this was a rough winter for the animals. The NPI revealed in a statement that both calves and adults on Svalbard displayed low body weights and an absence of fat on their backs — a clear indication that they hadn’t been getting enough to eat. There were also few pregnant females. What’s more, researchers noticed that the reindeer seemed to be modifying their behavior in response to the rainy winters and a lack of fjord ice. For one, the animals were grazing on seaweed and kelp that remained accessible along the shoreline — though these food sources are not particularly nutritious and can cause digestive distress in reindeer. The animals were also climbing up steep mountains in search of food, which the researchers refer to as a “mountain goat strategy.” But reindeer are not as sure-footed as mountain goats, putting them at risk of falling. Finally, NPI researchers noted that the animals were migrating further to find food. Svalbard’s reindeer are not the only ones suffering. Around the world, reindeer and caribou — which belong to the same species but differ in their behavior and geographic range — have plummeted by 56 percent.

Caribou and Muskoxen May Slow Biodiversity Loss As Arctic Warms

Rapidly warming temperatures in the Arctic and the loss of sea ice resulting from climate change are causing sharp declines in biodiversity, including among plants, fungi and lichen. But a new study published in Science in June 2023, found the presence of caribou and muskoxen helps to reduce the rate of loss by roughly half. Co-author Christian John of the University of California, Santa Barbara told AFP the results showed that "in some cases 'rewilding' (reintroduction of large herbivores) may be an effective approach to combating negative effects of climate change on tundra diversity." [Source: Issam Ahmed, AFP, June 23, 2023]

Issam Ahmed of AFP wrote: The paper was the result of a 15-year-long experiment that began in 2002 near Kangerlussuaq, a small settlement of around 500 people in western Greenland. An international team of scientists used steel fencing to set up 800-square-meter plots, or about a fifth of an acre, to exclude or include herbivores and measure the impact on the surrounding environment. They also used "passive warming chambers," which act like miniature greenhouses to raise the temperature a few degrees, to see how biodiversity might fare under conditions even warmer than today. Herbivores were given access to some warmed plots and not others.

Sadly, tundra community diversity declined across the board over the course of the study, both as a direct result of warming but also changing precipitation patterns associated with melting ice, and the increasing shrub cover in the tundra squeezing out other species. However, "tundra community diversity dropped at almost double the rate in plots where herbivores were excluded compared to plots where herbivores were able to graze," said John.

In the warmed plots, the difference was yet more dramatic. Diversity declined by about 0.85 species per decade when herbivores were excluded, whereas this decline was only about 0.33 species per decade when they were allowed to graze. The scientists attributed this to herbivores keeping species such as shrubs, dwarf birch and gray willow in check so that other plants could better flourish. "Efforts focused on maintenance or enhancement of large herbivore diversity may therefore under certain conditions help mitigate climate change impacts on at least one important element of ecosystem health and function: tundra diversity," wrote the team.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025