DEER FAMILY

The deer family includes deer, reindeer and elk. The largest deer are moose, which can weigh nearly a ton, and the smallest is the Chilean pudu, which is not much larger than a rabbit. Deer belong to the family “Cervidae”, which is part of the order “Artiodactyla” (even-toed hoofed mammals). “Cervidae” are similar to “Bovidae” (cattle, antelopes, sheep and goat) in that they chew the cud but differ in that have solid horns that are shed periodically (“Bovidae” have hollow ones).

A male deer is called a buck or stag. A female is called a doe. Young are called fawns. A group is called a herd. Deer don't hibernate and sometimes group together to stay warm. Particularly cold winters sometimes kill deer outright, mainly by robbing them of food, especially when a hard layer of ice and snow keeps them from getting at food.

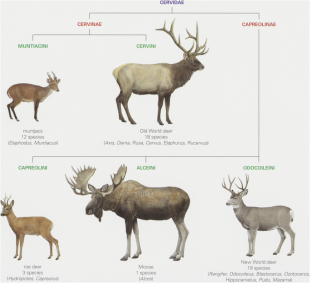

The family Cervidae, commonly referred to as "the deer family", consists of 23 genera containing 47 species, and includes three subfamilies: Capriolinae (brocket deer, caribou, deer, moose, and relatives), Cervinae (elk, muntjacs, and tufted deer), and Hydropotinae, which contains only one extant species (Chinese water deer). According to Animal Diversity Web: However, classification of cervids has been controversial and a single well-supported phylogenetic and taxonomic history has yet to be established. Cervids range in mass from nine to 816 kilograms (20 to 1800 pounds), and all but one species, Chinese water deer, have antlers. With the exception of caribou, only males have antlers and some species with smaller antlers have enlarged upper canines. In addition to sexually dimorphic ornamentation, most deer species are size-dimorphic as well with males commonly being 25 percent larger than their female counterparts. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Cervids have a large number of morphological Synapomorphies (characteristics that are shared within a taxonomic group), and range in color from dark to very light brown; however, young are commonly born with cryptic coloration, such as white spots, that helps camouflage them from potential predators. Although most cervids live in herds, some species, such as South American marsh deer, are solitary. The majority of species have social hierarchies that have a positive correlation with body size (e.g., large males are dominant to small males). /=\

Cervids are widely distributed and are native to all continents except Australia, Antarctica, and most of Africa, which contains only a single sub-species of native deer, Barbary red deer. Cervids have been introduced nearly worldwide and there are now six introduced species of deer in Australia and New Zealand that have been established since the mid 1800s.

Cervids live in a variety of habitats, ranging from the frozen tundra of northern Canada and Greenland to the equatorial rain forests of India, which has the largest number of deer species in the world. They inhabit deciduous forests, wetlands, grasslands, arid scrublands, rain forests, and are particularly well suited for boreal and alpine ecosystems. Many species are particularly fond of forest-grassland ecotones and are known to reside a variety of urban and suburban settings. /=\

The lifespan of most cervid ranges from 11 to 12 years, however, many are killed before their fifth birthday due to various causes including hunting, predation, or motor vehicle collisions. In most species, males have shorter lifespans than females and this is likely a result of intrasexual competition for mates and the solitary nature of most sexually dimorphic males, resulting in increased risk of predation. However, recent studies show that sex-biased mortality rates are tightly linked to local environmental conditions. Captive deer tend to outlive their wild counterparts as they are subjected to little or no predation and have access to an abundant supply of food. The lifespan of cervids decreases as the number of deer exceeds the local environments carrying capacity. In this case, young and old cervids tend to suffer from starvation, as stronger, middle-aged deer outcompete them for forage.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DEER (CERVID) BEHAVIOR, FEEDING AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ROE DEER: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SIKA DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MUSK DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PERFUME, MEDICINE, FARMS factsanddetails.com ;

RED DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ELK: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

DEER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND CARIBOU: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND CARIBOU BEHAVIOR: MIGRATIONS, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK): CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HABITAT, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS, DRUNKENESS factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) AND HUMANS: ATTACKS, RAMPAGES, CAR CRASH TESTS factsanddetails.com

DEER IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com ;

DEER IN INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA factsanddetails.com ;

DEER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

MUNTJACS (BARKING DEER): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

Deer History and Taxonomy

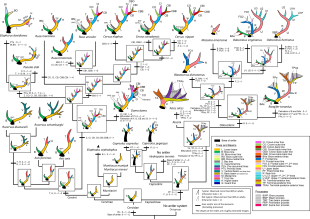

As is the case with many families within the order Artiodactyla, a well-supported history and taxonomy of Cervidae has yet to be established. According to Gilbert et al. (2006), which used mitochondrial and nuclear DNA to determine the phylogenetic relationship between species, Cervidae can be broken down into two subfamilies, Cervinae and Capriolinae. However, Hernandez-Fernandez and Vrba (2005) provide support for three subfamilies, Hydropotinae, Cervinae, and Odocoileinae. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

It is believed ancestral deer were small, solitary, selective browsers of dense forests; more recent species are larger, more gregarious, grazers of open woodlands. According to Animal Diversity Web: Regardless, most recent classification attempts incorporate differences in the gross morphology of the metacarpals. Those species that retain the proximal portion of the lateral metacarpals are grouped into Plesiometacarpalia (Cervinae and Cervinae), and those that retain the distal portion of the lateral metacarpals are grouped into Telemetacarpalia (Odocoileinae and Hydropotinae). Traditionally, Cervidae has consisted of three subfamilies: Capreolinae (brocket deer, caribou, deer, moose, and relatives), Cervinae (elk, muntjacs, and tufted deer), and Hydropotinae (water deer). The family Moschidae, the musk deer, which are known for their large upper canines, was once a subfamily of Cervidae but is now considered a separate family. /=\

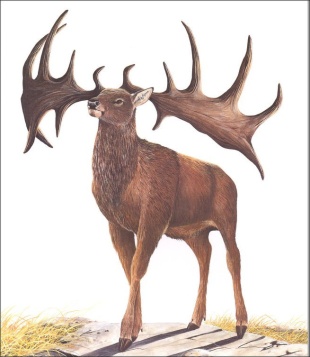

All extinct and living deer are thought to have evolved during the Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago) and early Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago) from a Eurasian ancestor known as protodeer (Dicroceridae). The first true cervids appeared about 20 million years ago during the Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago), which is around the same time cervids began moving from Asia into Europe and North America. Early cervids began movement into North America via the Berigian Land Bridge and became relatively common in North America during the early Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago). Some Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) cervids had spectacular antlers. For example, the "Irish elk" Megaloceros, which was not an elk and was not restricted to Ireland, had large palmate antlers with a span up to 3.7 meters and a weight around 45 kilograms. In North America, the giant stag moose had tripalmate antlers that spanned almost five feet in width. Another extinct deer with spectacular antlers was Eucladoceros, a large animal whose antlers were made up of many of irregularly branched tines. Synapomorphies (characteristics found in an ancestral species and shared by their evolutionary descendants) of extant cervids include deciduous antlers, no upper incisors, two lacrimal orifices on or outside the orbital rim, and an ethmoidal or antorbital vacuity that terminates the lacrimal short of nasal articulation. /=\

Artiodactyls (Even-Toed Ungulates)

Deer are Artiodactyls. Artiodactyls are the most diverse, large, terrestrial mammals alive today. According to Animal Diversity Web: They are the fifth largest order of mammals, consisting of 10 families, 80 genera, and approximately 210 species. As would be expected in such a diverse group, artiodactyls exhibit exceptional variation in body size and structure. Body mass ranges from 4000 kilograms in hippos to two kilograms in lesser Malay mouse deer. Height ranges from five meters in giraffes to 23 centimeters in lesser Malay mouse deer. [Source: Erika Etnyre; Jenna Lande; Alison Mckenna; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Artiodactyls are paraxonic, that is, the plane of symmetry of each foot passes between the third and fourth digits. In all species, the number of digits is reduced by the loss of the first digit (i.e., thumb), and many species have second and fifth digits that are reduced in size. The third and fourth digits, however, remain large and bear weight in all artiodactyls. This pattern has earned them their name, Artiodactyla, which means "even-toed". In contrast, the plane of symmetry in perissodactyls (i.e., odd-toed ungulates) runs down the third toe. The most extreme toe reduction in artiodactyls, living or extinct, can be seen in antelope and deer, which have just two functional (weight-bearing) digits on each foot. In these animals, the third and fourth metapodials fuse, partially or completely, to form a single bone called a cannon bone. In the hind limb of these species, the bones of the ankle are also reduced in number, and the astragalus becomes the main weight-bearing bone. These traits are probably adaptations for running fast and efficiently. /=\

Artiodactyls are divided into three suborders. Suiformes includes the suids, tayassuids and hippos, including a number of extinct families. These animals do not ruminate (chew their cud) and their stomachs may be simple and one-chambered or have up to three chambers. Their feet are usually 4-toed (but at least slightly paraxonic). They have bunodont cheek teeth, and canines are present and tusk-like. The suborder Tylopoda contains a single living family, Camelidae. Modern tylopods have a 3-chambered, ruminating stomach. Their third and fourth metapodials are fused near the body but separate distally, forming a Y-shaped cannon bone. The navicular and cuboid bones of the ankle are not fused, a primitive condition that separates tylopods from the third suborder, Ruminantia. This last suborder includes the families Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Cervidae, Moschidae, Antilocapridae, and Bovidae, as well as a number of extinct groups. In addition to having fused naviculars and cuboids, this suborder is characterized by a series of traits including missing upper incisors, often (but not always) reduced or absent upper canines, selenodont cheek teeth, a three or 4-chambered stomach, and third and fourth metapodials that are often partially or completely fused. /=\

See Separate Article: ARTIODACTYLS (EVEN-TOED UNGULATES): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Deer Characteristics

There is a great deal of physical diversity within the family Cervidae. According to Animal Diversity Web: Typically members have compact torsos and very powerful elongated legs that are well suited for woody or rocky terrain. Deer are primarily browsers (foraging on broad leaf plant material), and their low- (brachydont) to medium-crowned (mesodont) selenodont cheek teeth are highly specialized for browsing. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Cervids lack upper incisors and instead have a hard palate. The anterior portion of the palate is covered with a hardened tissue against which the lower incisors and canines occlude. They have a 0/3, 0-1/1, 3/3, 3/3 dental formula. Other notable features of cervids include the lack of a sagittal crest and the presence of a postorbital bar.

Some deer have hairs that stand erect and give off distinctive and strong odors. The top speed of a deer is around 30 miles per hour. Some deer can reach speeds of 40mph for short bursts and gallop for three or four hours at a speed of 25mph. Some deer can vertically jump 25 feet. The tracks of stags are bigger and broader than those of does. They have a more swaggering walk.

Deer Antlers

Antlers are bones that grow outside of the body, and every year they fall off and grow back. Unlike horns, which are made fingernail-like keratin, antlers are made of same materials as bone inside the body and are shed in a continuous cycle. For a large part of the year, they are made up of living tissue whereas horns are made of dead, and remain attached to the animal year after year. Also, horns, which adorn rams, goats, cows, and many other mammals, are part of the skull itself and never shed. Horns grow slightly larger each year as new material is added onto the base. In more than a few horned species, such as yaks, oryx, and duikers, females also have horns. [Source: Jason Bittel, National Geographic, January 6, 2023 **]

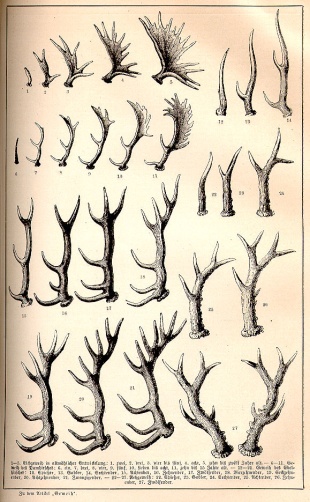

With the exception of Chinese water deer, all male cervids have deciduous antlers and caribou are the only species in which both males and females have antlers. Many deer annually grow new antlers in the spring and shed their old ones in the fall. The antlers of some species are covered by "velvet" (soft skin laced with blood vessels and covered with fine hair), which provided the antlers with calcium and other nutrients from the body. The antlers reach full growth and peak hardness in the early fall. After this the blood supply to the velvet is cut off. The velvet is rubbed off on bushes and trees in August after the summer.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Antlers grow from pedicels, boney supporting structures that grow on the lateral regions of the frontal bones. In temperate-zone cervids, antlers begin growing in the spring as skin-covered projections from the pedicels. The dermal covering, or "velvet," is rich in blood vessels and nerves. When antlers reach full size, the velvet dies and is rubbed off as the animal thrashes its antlers against vegetation. Antlers vary from simple spikes, such as those in munjacs, to enormous, complexly branched structures, such as those in moose. Antler structure changes depending on species and the age of the individual bearing them. Although Chinese water deer are the only species without antlers, they have elongated upper canines that are used to attract mates. Antlers typically emerge at one year of age. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Antlers have their downsides, especially for animals living near people. Deer, moose, and red deer frequently become caught on branches or tangled up in fencing, garbage, or even Christmas decorations. Every year, wildlife managers and biologists get reports of cervids whose antlers have become locked together. Males in this situation often die from their injuries, starvation, or attacks from predators. **

Why Do Deer Have Antlers and the Cost of Having them

Antlers are used during male-male competition for mates during breeding season, and are shed soon afterwards. They are a kind of symbol of strength and virility intended to impress females and intimidate rivals. They are used by males to battle one another in the rutting (mating season). After the rutting season is over in the fall, the antlers fall off. Except for reindeer and caribou, only males grow antlers. Males usually grow spike like antlers when they are two and develop a full rack when they are full grown are age six. Males of the genus Muntiacuc have both antlers and long, fang-like upper canines that are used in social displays. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Matthew Every wrote in Outdoor Life: The reason cervids have antlers is for mating purposes. Because they live in competitive societies and mate like spring breakers, males need something to work out their differences with and attract the ladies. Big pointy antlers are just the ticket, and while it’s important to note that they aren’t trying to kill each other, deer, elk, moose, and other cervids spend their respective mating seasons using their headgear to duke it out for cows or does.[Source: Matthew Every, Outdoor Life, July 8, 2019]

Two fast-growing bones on your head are going to cost something, and for deer, elk, and other cervids this cost is huge. Protein from food is, of course, a factor and is a reason that nutrition is so important for healthy antler growth, but there’s another process, more to do with minerals, that takes the concept of recovery to another level. It’s called mobilization, and it has to do with nutrients being drawn from other bones to supplement antler growth. The MSU Deer Lab sums this up best on its website: “During mobilization, calcium and phosphorus are ‘mobilized’ and transferred from skeletal sites, such as rib bones, to be used in the production of antlers. The skeletal sites are replenished later through dietary intake.”

In other words, to grow their antlers so fast, whitetails and other cervids need to borrow minerals like calcium and phosphorus from non-weight-bearing bones. This takes an incredible amount of energy for something that is not exactly essential for reproduction, and when you stop and think about it, it’s amazing that so much of a male cervid’s life revolves around acquiring nutrients and minerals to grow his antlers and then recover. After the growth is complete, they have to replenish those minerals from somewhere, and while the role of vitamins and minerals in a deer’s diet is still being studied, it is known that the soil plays a big part. Soils with poor mineral content, make it harder for recovery, and in a lot of cases where soil quality is low, supplemental feeds help to make mobilization a little more efficient.

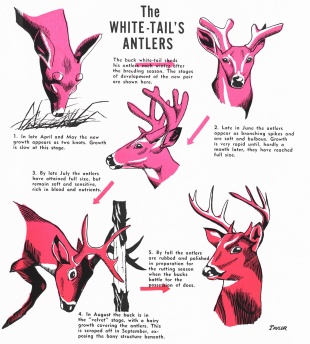

Deer Antler Growth Cycle

Matthew Every wrote in Outdoor Life: Male cervids have two soft spots on their skulls called pedicles. In the spring or early summer, two nubs form at the pedicles and are covered in a sensitive type of skin called velvet. The velvet is packed with blood vessels that rapidly bring blood, oxygen, and nutrients that the antlers need for growth. The antlers grow from the tip, starting as cartilage and then calcify into hard bone as they go. [Source: Matthew Every. Outdoor Life, July 8, 2019]

During the velvet stage, cervids try to avoid contacting their antlers with just about everything. Injuries to velvet during antler growth can cause changes. Abnormalities, and injuries to other parts of a deer’s body, such as the leg, can affect antler growth too. Once the antlers are fully grown, the velvet is cut off from the blood supply, and it dries up and dies before getting rubbed off by the animal. By the time the rut kicks off, a deer’s antlers are actually dead bone. Throughout the season, the connections between the pedicles and the antlers weaken, and usually during the winter, well after mating, the antlers fall off. In a matter of weeks, the cycle starts all over again.

Depending on the photoperiod, or amount of sunlight during the day that a male cervid is exposed to, they will either be growing or shedding their antlers. Generally, the more sunlight there is, the more the antlers will grow. The change in light triggers the pineal gland to tell the pituitary gland to release more testosterone. With the boost in testosterone, deer antlers can grow up to two inches per week, and in some cases, bull moose can put on a pound of bone per day during the peak of their growth cycle. Here is a general timeline of the antler growth cycle, although, depending on the area or species, the exact months may differ. (For example, moose don’t start growing new antlers until roughly two to three months after shedding.

April through May (Spring): Antler growth begins from the permanent bases on the male cervid’s skull. It is slow to start, growing from the tip out.

June to July (Mid Summer); With the increase in sunlight, growth increases rapidly. The buck or bull’s energy is focused on growth.

September (Late Summer): As fall draws near and the days get shorter, growth slows. The antlers become mineralized, harden up, and blood eventually stops flowing to the velvet. The velvet dries, and afterward, it takes about 24 hours for a buck or bull to shed his velvet.

October-December (Fall to Winter): The hardened antlers are now dead bone, and at this point bucks or bulls use them for the things that they do best during the rut: rubbing trees, fighting, showing off to females, and getting into all sorts of trouble.

January-March (Late Winter to Early Spring): Male cervids can only maintain a connection between the pedicle and the antler when testosterone levels are high, so as daylight hours dwindle, levels taper off, the connection weakens. Eventually, the antlers are shed, and without them, the pedicles are open wounds. Scabs form, and in a matter of weeks, antler growth begins again.

How Do Deer Antlers Grow So Fast?

Antlers are bones that grow extremely fast outside of a mammals body. For whitetails, at the peak of development, antlers grow almost a centimeter (a quarter of an inch) per day; for bull elk it can be more than 2.5 centimeters (an inch). A combination of nutrition, genetics, and age are the main factor that influence growth. Matthew Every wrote in Outdoor Life: The perfect combination of these factors is still hard to track, but when the formula is right, a buck or bull’s antlers will grow abnormally large. Here’s a breakdown of how the big three factors for antler growth work: [Source: Matthew Every, Outdoor Life, July 8, 2019]

Nutrition: The better the habitat, the bigger the antlers will be at any age. As a general rule, protein-rich forage contributes immensely to antler growth. According to the MSU Deer Lab and a study from Texas, on a 16 percent protein diet, bucks consistently grew antlers that were twice as big as bucks on an 8 percent protein diet. In four years, the bucks that had more protein were sporting racks that scored 20 points higher on the Boone and Crockett scale. Local native forage varies depending on where you hunt, and in some cases, agriculture and food plots play the most significant role in local deer diet. In terms of wild, high-quality forage some examples cited by the QDMA are blackgum in the north, beggar’s lice in the south, and partridge peas into parts of the Midwest. Of course, acorns and other mast are great across the board. Seasonal changes and rainfall will affect the levels of protein in forage and, as stated above, supplemental feeding is often used to support antler growth.

Genetics: This one is thrown around a lot at deer camp, but it’s a tricky thing to define in the wild. While it’s easy to think about big-racked bucks producing more big-racked bucks, the devil is in the details. Nutrition and habitat both impact growth regardless of genetics, and unless you are selectively breeding deer in captivity, it’s hard to tell what is doing what. What we do know is that, just like other animals, genetics are a two-part equation, and both the mother and the father play equally important roles. Genetics will determine the shape and size of the antler, and studies have shown that big antlers are hereditary (more on this later). However, the other external factors impact antler growth so greatly that it’s not the best thing to focus on. The upshot: small deer in your area are most likely not genetically inferior, they’re probably just be coming up short on the other two factors, age, and nutrition.

Age: Before a buck can be called a monster, a hawg, a toad, or booner, it has to survive a few seasons. Simply put, dead bucks can’t grow antlers. Like the best things in life, antlers get better with time. A whitetail buck will reach generally reach his prime in four to six years, and for elk, it is more like eight to twelve. Age is one of the easiest factors humans can manipulate to see bigger antlers.

Predators of Deer

Deer are hunted by humans and are prey of large carnivores such as tigers, cougars, wolves and occasionally bears. Deer meat is called venison. People have made buckskin jackets, moccasins and other items of clothing from deer hide.

Known Predators of deer include lynxes, caracals, coyotes, gray wolves, grizzly bears, mountain lionss, jaguars, tigers, large raptors, ocelots, and humans. According to Animal Diversity Web: In areas where large carnivores (mainly eat meat or animal parts), populations have not been significantly reduced by humans, predation represents an important cause of mortality for cervids. For many species, predation is the primary means of controlling population densities. For many cervids, predation on calves is especially important in limiting population size, and much of this predation is accomplished by smaller carnivores (e.g., Canada lynx, caracal, and coyote). It is difficult, however, to estimate the natural effect of predation on cervids, as predator populations in many locations have been significantly reduced or eliminated by humans. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

To avoid predation, gregarious species foraging in open habitats group together to face potential threats. Solitary species avoid predators by foraging in or near the protective cover of woodland or brush habitat. The young of most cervids have spots or stripes on their fur, which helps camouflage them in dense vegetation. All species give a harsh bark, which serves as an alarm to members of their own species. Pronking (i.e., continuously jumping high into the air) and tail-flaring is a known response to predators at close range, as well as when individuals are startled. Cervids also have acute senses of sight, hearing, and smell, which helps them avoid potential predators. /=\

Ecosystem Roles of Deer

Cervids are an important food source for many predators throughout their geographic range. For example, one study showed that over 80 percent of the feces of gray wolves in Algonquin Park in Canada contained the remains of white-tailed deer. Cervids are host to a variety of endoparasites, including parasitic flatworms (Cestoda and Trematoda) and many species of roundworm (Nematoda) spend at least part of their lifecycle in the tissues of cervid hosts. Cervids are also vulnerable to various forms of parasitic arthropods including ticks (Ixodoidea), lice (Phthiraptera), mites (Psoroptes and Sarcoptes), keds (Hippoboscidae), fleas (Siphonaptera), mosquitoes (Culicidae), and flies (Diptera). In addition, cervids compete with other species for food and other resources, which can effectually limit both inter- and intraspecific population growth. /=\

Cervids play an integral role in the structure and function of the ecosystems in which they reside, and some species have been shown to alter the density and composition of local plant communities. For example, on Isle Royale National Park, MI, moose (Alces alces) have been shown to alter the density and composition of foraged aquatic plant communities, and fecal nitrogen transferred from aquatic to terrestrial habitats via the ingestion of aquatic macrophytes increases terrestrial nitrogen availability in summer core areas. Foraging by cervids has been shown to have a significant impact on plant succession, and plant diversity is greater in areas subjected to foraging. As a result, foraging might lead to shifts from one plant community type to another (e.g., hardwoods to conifers). In addition, moderate levels of foraging by cervids may increase habitat suitability for members of their own species. For example, litter from foraged plants decomposes more quickly than non-browsed, thus increasing nutrient availability to the surrounding plant community. Moreover, nutrient inputs from urine and feces have been shown to contribute to longer stem growth and larger leaves in the surrounding plant community, which are preferentially fed upon during subsequent foraging bouts. Finally, research has shown that the decomposition of cervid carcasses can result in elevated soil macronutrients and leaf nitrogen for a minimum of two years. /=\

Deer, Humans and Conservation

Humans have utilize deer for food and skins. Their body parts are source of valuable material. They are an ecotourism draw. According to Animal Diversity Web: Humans have a long history of exploiting both native and exotic deer species, having hunted them in every geographic region in which they occur. They are often hunted for their meat, hides, antlers, velvet, and other products. As humans began to rely more on agriculture, their dependence on deer species as a food source decreased. However, in areas where climate prohibits wide-scale agriculture, such as in the Arctic, deer species such as caribou are still relied upon for food, clothing, and other resources. In the past, caribou have even been domesticated by nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), peoples in the high Arctic. Today, many cervid species are hunted for sport rather than necessity. Several species have also been domesticated as harness animals, including caribou and elk. Finally, cervids play an important role in the global ecotourism movement as various species of deer are readily observable throughout much of their native habitat. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Many species of cervid are viewed as agricultural pests, especially in areas where they have become overpopulated due to habitat alterations and lack of natural predators. The effects of deer on crops can be devastating. Most cervid species are forest dwellers and as a result, they can cause damage to timber by browsing, bark-stripping, and velvet cleaning. In addition, deer-vehicle collisions result in significant harm to the health and personal property of those involved. Many cervids carry diseases that can be transmitted to domestic livestock and certain species, including white-tailed deer, elk, and Javan rusa, have been introduced outside of their geographic ranges, causing significant harm to native plant and animal communities. /=\

The IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species lists 55 species of Cervidae, two of which are listed as extinct and one is considered critically endangered. Of the remaining 52 species, eight are endangered, 16 are vulnerable, and 17 are listed as "least concern". The remaining 10 species are listed as "data deficient". Many more local deer population are on the cusp of extirpation, which could lead to inbreeding in adjacent populations. According to the IUCN, major threats of extinction for cervids includes over exploitation due to hunting, habitat loss (e.g., logging, conversion to agriculture, and landscape development), and resource competition with domestic and invasive animals. In addition, climate change has begun to contract species ranges and forced some species of cervid to move poleward. For example, moose, which are an important ecological component of the boreal ecosystem, are notoriously heat intolerant and are at the southern edge of their circumpolar distribution in the north central United States. Since the mid to late 1980's, demographic studies of this species have revealed sharp population declines at its southernmost distribution in response to increasing temperatures. In addition, climate change has allowed more southerly species to move poleward, which increases competition and disease transmission at range interfaces of various species (e.g., white-tailed deer and moose). Finally, cervids are an important food source for a number of different carnivores. As cervid populations decline, so too will those animals that depend on them. CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) lists 25 species of cervid under appendix I. /=\

Deer in Europe and Northern Asia

There are three main species of deer found in Europe and western Asia: 1) red deer; 2) roe deer; and 3) fallow deer. Fallow deer are found in southern Europe and northern Africa. They stand about three feet at the shoulder, and have a white-spotted summer coat and flat gooselike antlers.

Red deer were featured in the Robin Hood stories. Ranging across Europe as far east as Iran and as far south as northern Africa, they are distinguished by a long fringe of hair at the animal's throat. The hart (stag) stands about four feet tall at the shoulder and has spectacular many-pointed antlers. They fight fiercely and roar in the rutting season. They let out booming bellowing roars—as often as 3,000 times a day—to lure females. Their defensive calls often attracts unhitched females.

Roe deer have long been a favorite of hunters. They range from Britain across the length of Russia and Asia to the Pacific Ocean. Males stand two feet tall at the shoulder are known for making circular trails called "doe rings" when they pursue females in the mating season.

The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate Asia occurs in the mixed deciduous forests, mountain coniferous forests, and taiga bordering North Korea, Manchuria (Northeastern China), and the Ussuri Region (Russia). These are among some of the richest deciduous and coniferous forests in the world where one can find Siberian roe deer, sika deer, elk, and moose. Asian caribou occupy the northern fringes of this region along the Sino-Russian border. Deer such as the sika deer, Thorold's deer, Central Asian red deer, and elk have historically been farmed for their antlers by Han Chinese, Turkic peoples, Tungusic peoples, Mongolians, and Koreans.

Sika deer are a forest deer deer found in East Asia from Siberia south through China to Vietnam and Taiwan to the south and Japan to the east. These deer are divided into more than a dozen different regional subspecies, of which seven are found in Japan. The largest is the ezo-jika, which lives in Hokkaido. Sika are browsers that live primarily in forests — but are often seen roaming around farmland — and feed on tree leaves, fruits, flowers, buds, acorns and nuts. They have large eyes and a strange haunting whistle. Adults can have large stately antlers. White hairs on the rumps can flare out like chrysanthemums when the animals are excited.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025