DEER BEHAVIOR

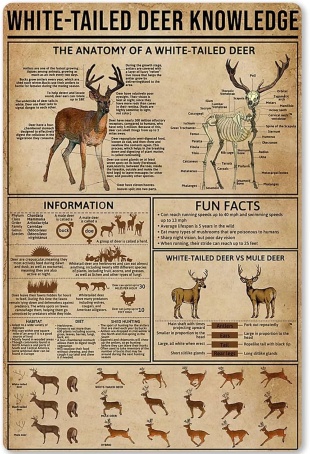

The deer family includes deer, reindeer and elk. The largest deer are moose, which can weigh nearly a ton, and the smallest is the Chilean pudu, which is not much larger than a rabbit. Deer belong to the family “Cervidae”, which is part of the order “Artiodactyla” (even-toed hoofed mammals). “Cervidae” are similar to “Bovidae” (cattle, antelopes, sheep and goat) in that they chew the cud but differ in that have solid horns that are shed periodically (“Bovidae” have hollow ones).

Deer are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Although active throughout most of the day, cervids are typically classified as crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk). Species living in seasonal climates spend most of their time during the winter and early spring resting, as forage during this time is limited and of poor quality. During late spring, when fresh forage is available, deer spend less time resting and significantly increase their activity rates. Activity patterns are based on seasonal metabolic rates and energy costs, which change from season to season. During summer, energy requirements are high and thus they spend more time foraging. Deer are typically more aggressive during food shortages, in areas of high population density, and during mating season. They often make themselves appear more intimidating by raising their body hair (i.e., piloerection) through contraction of the arrector pili muscle, which makes them appear larger. /=\

Larger, more aggressive males tend to gain dominance over others, which results in access to females during mating season and consequently, higher reproductive rates. During male-male competition for mates, larger males are dominant, and if two animals are the same size, the individual with the largest set of antlers gains dominance, unless the larger individual is past his prime. In some species, individuals may encircle one another with a stiff-legged stride while making a high-pitched whine or low grunting sound and is meant to intimidate rival individuals. During mating season, male cervids often scrape the ground with their forelimbs to advertise their presence and availability to potential mates. Scrapes are usually made by dominant males and consist of a “sign-in”, which involves chewing on a branches overhanging the scrape, pawing the scrape underneath the branch, and rubbing glandular secretions on the scrape, which advertises his presence. In some cases, males may urinate, ejaculate, or defecate in the scraped area. Females are most aggressive when they have offspring with them. They are very protective of their young and readily defend their offspring against both inter- and intraspecific threats. /=\

Social organization in cervids is highly variable and in some cases is based on season. Although most species remain in small groups, large herds may results during feeding, after which individuals tend to disperse. In gregarious cervids, males join calf-cow herds during mating season to mate then quickly return to their solitary lifestyles. During summer, many cervids remain in small groups with some species becoming solitary. During winter, cervids may congregate into larger families or herds, which likely helps reduce vulnerability to predation. Dominant individuals signal their status in the hierarchy with a “hard look”, which involves staring directly at a potential rival while laying their ears back with his or her head lowered. If the rival individual is not willing to challenge for dominance, they slowly back away and refuse eye contact. If the “hard look” is successful, he or she will drop and extend their head toward the subordinate individual, after which a charge may occurs. /=\

Similar to other endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them), animals, many cervids migrate according to proximal cues, such as photoperiod. These proximal cues serve as indicators for various ultimate factors, such as changes in season, which can affect the abundance of pests, predators, and forage. Although the costs of migration can be great, benefits often include increased individual survival rates and increased reproductive fitness. One of the best-studied cases of cervid migration is that of barren-ground caribou, which travel an annual distance of more than 500 kilometers. Unfortunately, seasonal migration is cued by photoperiod while onset of plant-growing season is cued by temperature. If the growing season of species-specific resources is not precisely matched to the initiation of migration, changes in plant phenologies may detrimentally impact the long-term survival of migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), animals. For example, increasing mean spring temperatures in West Greenland appear to have resulted in a mismatch between caribou migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), cues and the onset of spring growing season for important forage plants. Evidence suggests that caribou migrations are not advancing at a comparable rate with forage plants and as a result, calf production in West Greenland caribou has decreased by a factor of four. /=\

RELATED ARTICLES:

DEER (CERVIDS): CHARACTERISTICS, ANTLERS, HISTORY, ECOSYSTEM ROLE, HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

ROE DEER: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SIKA DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MUSK DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PERFUME, MEDICINE, FARMS factsanddetails.com ;

RED DEER: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ELK: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

DEER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND CARIBOU: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND CARIBOU BEHAVIOR: MIGRATIONS, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS factsanddetails.com

REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK): CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HABITAT, SUBSPECIES factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, PREDATORS, DRUNKENESS factsanddetails.com

MOOSE (ELK) AND HUMANS: ATTACKS, RAMPAGES, CAR CRASH TESTS factsanddetails.com

Deer Senses and Communication

Deer sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with vision, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Cervids use three main types of communication: vocal, chemical, and visual. Vocal communication is used primarily during times of fear or excitement. The most common form of vocal communication is barking, which is typically used in response to a disturbance, such as visual contact with a predator or a disturbing noise. Barking is also used as an expression of victory after a competitive interaction between two males. Cervids also communicate through a variety of hormone and pheromone signals. For example, male cervids demarcate territory with glandular secretions rubbing their face, head, neck, and sides against trees, shrubs, or tall grasses.

Cervids also use visual communication, known as scraping. Scraping is primarily used during mating season by males to advertise their presence and availability to females. To create a scape, males paw the ground with the forelimbs, producing patches of bare ground about 0.5 meters to 1.0 meters in width. Typically, scrapes are marked with a secretion from the interdigital glands located between their hooves. In response to a potential threat, some species stand with their body tensed and rigid, while leaning slightly forward, which signals the potential threat to members of their own species. /=\

Deer Food and Eating Behavior

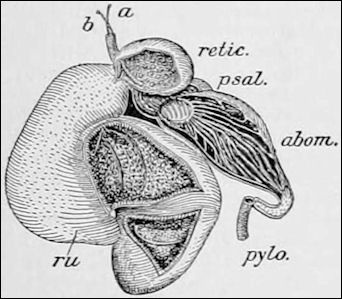

All cervids are obligate herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), which means their digestive systems can not process meat. Their diets include grass, small shrubs, and leaves. Some are also classified as folivores (eat mainly leaves) or lignivores (eat wood). All cervids chew their cud, have three or four-chambered stomachs, and support microorganisms that breakdown cellulose. In addition to the true stomach, or abomasum, cervids have three additional chambers, or false stomachs, in which bacterial fermentation takes place. Unlike many other ruminants, cervids selectively forage on easily digestible vegetation rather than consuming all available food. Some cervids store or cache food in their bodies.[Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: In ruminants, the digestion of high-fiber, poor-quality food occurs via four different pathways. 1) Gastric fermentation extracts lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, which are then absorbed and distributed throughout the body via the intestines. 2) Large undigested food particles form into a bolus, or ball of cud, which is regurgitated and re-chewed to help break down the cell wall of ingested plant material. 3) Cellulose digestion via bacterial fermentation results in high nitrogen microbes that are occasionally flushed into the intestine, which are subsequently digested by their host. These high-nitrogen microbes serve as an important protein source. 4) cervids can store large amounts of forage in their stomachs for later digestion.

Ruminants

Ruminant stomach

Cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread.

As ruminants evolved they rose up on their toes and developed long legs. Their side toes shrunk while their central toes strengthened and the nails developed into hooves, which are extremely durable and excellent shock absorbers.

Ruminants helped grasslands remain as grasslands and thus kept themselves adequately suppled with food. Grasses can withstand the heavy trampling of ruminants while young tree seedlings can not. The changing rain conditions of many grasslands has meant that the grass sprouts seasonally in different places and animals often make long journeys to find pastures. The ruminants hooves and large size allows them to make the journeys.

Describing a descendant of the first ruminates, David Attenborough wrote: deer move through the forest browsing in an unhurried confident way. In contrast the chevrotain feed quickly, collecting fallen fruit and leaves from low bushes and digest them immediately. They then retire to a secluded hiding place and then use a technique that, it seems, they were the first to pioneer. They ruminate. Clumps of their hastly gathered meals are retrieved from a front compartment in their stomach where they had been stored and brought back up the throat to be given a second more intensive chewing with the back teeth. With that done, the chevrotain swallows the lump again. This time it continues through the first chamber of the stomach and into a second where it is fermented into a broth. It is a technique that today is used by many species of grazing mammals.

Cervids tend to lose weight during winter due to a reduction in appetite and decreased forage quality and availability. However, many species found in habitats with minimal climatic variability exhibit a reduction in food intake and decreased metabolic rate during certain parts of the year. In habitats with abundant resources cervid home-range size does not change between seasons. However, in poor habitats winter ranges expand significantly, presumably to offset the decrease in forage quality and abundance that occurs during winter.

Ruminant Stomachs

Ruminants chew a cud and have unique stomachs with four sections. They do no digest food as we do, with enzymes in the stomach breaking down the food into proteins, carbohydrates and fats that are absorbed in the intestines. Instead plant compounds are broken down into usable compounds by fermentation, mostly with bacteria transmitted from mother to young.

The cub-chewing process begins when an animal half chews its food (mostly grass) just enough to swallow it. The food goes into the first stomach called the rumen, where the food is softened with special liquids and the cellulose in the plant material is broken down by bacteria and protozoa.

After several hours, the half-digested plant material is separated into lumps by a muscular pouch alongside the rumen. Each lump, or cud, is regurgitated, one at a time and animal chews the cud thoroughly and then swallow it again. This is referred to a chewing the cud.

When the food is swallowed for the second time it by passes through the first two chambers and arrives at the third chamber, the "true" stomach, where it is digested. As the chewed food moves through this chamber microbes multiply and produce fatty acids that provide energy and use nitrogen in the food to synthesize protein that eventually becomes amino acids. Vitamins, amino acids and nutrients created through chemical recombination then move in the intestine and pass through linings in the gut into the bloodstream.

Deer Eating Snakes, Fish and Beheaded Chicks

In June 2023, a 22-second video shared on Instagram showed, a white-tailed deer casually eating a snake in Texas. Emma Bryce wrote in Live Science: Deer aren't naturally built for catching animals or consuming meat. Instead they extract nutrients from cellulose, the fibrous ingredient that makes up the walls of plant cells, using their intricate four-chambered digestive system, and turn it into energy. But while certainly unusual, carnivorous behavior isn't unheard of. In fact, this creature is one in a surprisingly long line of deer that have shown a taste for blood. [Source: Emma Bryce, Live Science, June 16, 2023]

Before the snake-slurper was caught on film, a deer was filmed nibbling on a live fish, eventually swallowing it whole. In other footage, what appears to be a semi-tame deer doesn't think twice before accepting a chunk of steak from an al fresco diner, and gulping it down. Field cameras have captured images of deer seeming to nibble on dead rabbits, and nosing around gut piles left behind by hunters in the wild. These amount to more than just one-off observations. In 1988, researchers documented red deer in Scotland beheading seabird chicks and gnawing on their legs and wings.

In an account from 1976 that reads like a murder mystery, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) were blamed for the deaths of several well-chewed avian corpses that had been plucked off nearby mist nets belonging to researchers studying birds. This opportunistic mist-net hunting was confirmed in a study published in the American Midland Naturalist in 2000.

And a 2017 study described deer as one of the many scavengers at the site of a decomposing human corpse on an experimental body farm (a research facility where scientists study how bodies decompose.) In a chilling series of photographs, deer can be seen noshing on the gristly end of a human rib. Indian spotted deer have been observed crunching on the bones of wild animals too.

What's behind these meaty feasts? They may in fact be an entirely logical survival hack. Deer may lack the evolutionary capabilities to tackle, kill and tear apart prey — but prone or dead animals represent an easy target and a rich source of minerals, proteins, and fats compared to the plants that deer stomachs have to work exceptionally hard to process..

Researchers think these dietary detours may coincide with times when deer require more nutrients. One study published last year suggested they may eat meat when they need a growth spurt to develop or maintain their antlers. Having a more inclusive palate could also simply be a buffer against resource uncertainty and habitat change in the wild.

In any case, this trend goes beyond deer. An African antelope called the duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia) is known to eat lizards — and even occasionally feeds on carrion if the vultures don't get there first. Meanwhile those Scottish red deer had an accomplice to their chick beheadings: sheep. These farm animals were discovered not only decapitating but also stripping off their legs and wings, too. And in Africa, the phenomenon of bone-crunching giraffes is widespread.

Deer Mating and Reproduction

Normally-placid bucks become fierce warriors during the rutting (mating season). Their eyes become bloodshot, their necks puff out and they charge any threat with antlers down. Battling bucks run head on into one another with their antlers and keep charging until one backs off. Sometimes two bucks become locked up and die together. Scientist have been able to make a female red deer go into heat by playing a recording of a male red deer's mating roar. Deer fawns have dappled coats that match the broken light of the woodland floor.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Although most cervids are polygynous, some species are monogamous (e.g., European Roe deer). The breeding season of most cervids is short, with females coming into estrus in synchrony. In some species, males establish territories, which encompass those of one or more females. Males may then mate with those females who have territories within his own. In some cervids, females may form small groups known as harems, which are guarded and maintained by males, and in other species males simply travel between herds looking for estrus females. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Most male cervids cast their antlers regularly and do not mate again until their antlers are hard, which results in a regular birthing pattern, given that mating only occurs during certain months. Males use their antlers in combat to obtain and defend females. Sexual-size dimorphism is common in cervids. Males are larger than females in most species. Sexual Dimorphism is more pronounced in the most highly polygynous species. Cervids have a number of glands on their feet, legs, and faces that are used during intraspecific communication. Males of many cervid species significantly decrease forage intake during mating season, and evidence suggests that feeding cessation in males is linked to various physiological processes associated with chemical communication during the breeding season.

Sexual segregation is not uncommon in cervids; however, in some species permanent mixed-sex groups result in male-male competition for potential mates. In sexually segregating species, males join females only to copulate, leaving at the end of breeding season. Males establish dominance hierarchies among themselves, with the most dominant males achieving the most copulations. Males may hold dominance over a harem or territory and are often challenged by rival males. Male cervids significantly decrease forage intake during breeding season, which, in conjunction with being continually challenged by rivals males, ensures that dominance by any one individual is short lived. Antler growth is dependent on individual nutrition and evidence suggests that the size and symmetry of male antlers serves as an indicator of mate quality for females. /=\

Cervids living in temperate zones typically breed during late autumn or early winter. Seasonal breeders at lower latitudes, such as the chital, breed from late spring into early summer (e.g., April or May). Conception usually occurs during the first estrus cycle of the breeding season, and those that do not conceive will re-enter estrus every 18 days until they become pregnant. Species living in tropical climates, such as grey brocket deer, often do not have a fixed breeding season, and females may come in to estrus multiple times throughout the year.

Roe deer are the only cervid known to have delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). Cervids typically have from one to three offspring, and often, not all fetuses are carried to term, as the number of offspring born each year is dependent on population density and resource abundance.

Although some cervids are solitary, most are gregarious and live in herds that vary in size from a few individuals to more than 100,000 (e.g., caribou. Average group size depends on the demographic composition (i.e., sex and age) of the immediate population, the degree of inter- and intraspecific competition, and resource quality and abundance. Habitat segregation in cervids tends to peak during calving and significantly decreases soon afterward.

Deer Offspring and Parenting

Deer are iteroparous. This means that offspring are produced in groups such as litters multiple times in successive annual or seasonal cycles. Gestation in cervids ranges from 180 days in Chinese water deer to 240 days for elk, with larger species tending to have longer gestational periods. Age at weaning varies among species, with smaller species nursing for only two to three months and larger species nursing for much longer. For example Bornean yellow muntjacs are weaned by about two months of age and North American moose are weaned by about five months, however, erratic nursing may continue for up to seven months after birth. [Source: Katie Holmes; Jessica Jenkins; Prashanth Mahalin; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Parental care is provided by females. Pre-birth, pre-weaning and pre-independence provisioning and protecting are done by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. According to Animal Diversity Web: Body weight is more importance in determining sexual maturity in cervids than actual age; therefore, an individual's reproductive activity is dependent on environmental conditions and resource quality and abundance. Due to the energetic costs of lactation, this is especially true for females. In males, testes begin producing hormones at the end of the first year, and consequently, antler growth occurs during the end of the first year or the beginning of the second. However, because male-male competition plays a dominant role in cervid mating behavior, most males do not mate until they can outcompete rivals for access to females. /=\

As with many artiodactyls, cervids can be classified as either hiders or followers. Altricially born cervids are highly vulnerable to predation for the first few weeks of life. As a result, mothers hide their young in the surrounding vegetation as they forage nearby. Hider mothers periodically return to their young throughout the day to nurse and clean their calves. Females that give birth to multiple offspring hide each individual in separate locations, presumably to decrease the chance of losing multiple young to a predator. Once young become strong enough to escape potential predators they join their mother during foraging bouts. Some species are precocially born and are able to run only a few hours after birth (e.g., Rangifer tarandus). These species are often referred to as followers. /=\

Lactation is one of the most energetically expensive activities possible for female mammals and lactating cervids are often not able to consume enough food to maintain their body weight, especially during the first weeks of lactation. Typically, young are weaned earlier in smaller species; however, sporadic nursing may occur for up to seven months after birth. Young cervids may stay with their mother until she is about to give birth to the subsequent season’s offspring. In many species, females stay within their mother’s range after maturation, while males are forced to disperse. In most species, males do not provide any parental care to their offspring. /=\

Deer Getting High on Nitrous Oxide

A video uploaded on YouTube in January 2023 showed cavorting deer that had just inhaled nitrous oxide (laughing gas) fumes from a backyard leaf pile. The caption read: My deer are getting high on Nitrous Oxide. Watch them loose their minds!

In the clip uploaded by JS Project Wild, the deer are shown partying after their discovery of a giant pile of decomposing leaves, which naturally produces nitrous oxide emissions. According to AV Club: The first part of the video sees a lone deer digging at the snow-covered leaves, sticking its snout down in, then hopping around in delight. Over the selection of scenes that follow, taken in various seasons, we see whole groups of the animals wilding out on the fumes. They jump into each other, sprint back and forth like maniacs, and rear up to shadow box each other. [Source: Reid McCarter, The AV Club, January 14, 2023]

“Want to see deer lose their minds and act accordingly?” the video description reads. The uploader explains his “huge” decomposing pile includes some leaves that are over four years old. “I periodically ‘stir’ the pile with my loader tractor. However, [if] the leaves on the top are dry the deer will actually dig down to the rotting leaves and then inhale. It’s crazy — at different times in the video you will actually see them do this.”

The resulting deer behavior isn’t necessarily the most embarrassing thing we’ve ever seen these creatures do on video and it looks like they’re having a pretty good time. That they do all of this without littering the woods with little metal canisters or charging each other for access to the leaf pile only goes to show that the animals are much more responsible and equitable than we are.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025