BRITISH IN MALAYSIA

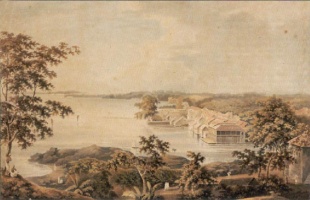

The British attempted to colonize Borneo as early as 1771 but did not gain a foothold in Malaysia until 1786 when the British East India Company procured the island if Penang (Pinang). The British gained control of what is now Malaysia when they threw out the Dutch in 1795, and over time through conquest and deals made with sultans. In 1819 Singapore was founded. It quickly became an important port.

Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei were all once part of he powerful kingdom of Brunei. In 1841, the Englishman James Brook was granted part of Sarawak by the Sultan of Brunei after he helped the sultan by putting down a tribal rebellion. In 1888, Sarawak, Brunei and North Borneo (Sabah) became British protectorates and were separated from the rest of Borneo by British-Dutch agreement.

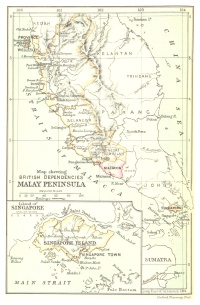

In 1826, Penang, Malacca and Singapore were combined as the Straits Settlement. These territories became quite valuable after the Suez Canal opened in 1869, providing a easy transportation route for Malayan tin and rubber to Europe. The British formally made Malaysia a colony in 1867. The Federated Malay States, in southern Malaya, was formed in 1895 after the British intervened in the fratricidal wars of the sultans. The British gained control over northern Malaya through an agreement made with Thailand in 1909 and merged all the territory under their control to form Malaya.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS IN MALAYSIA: PORTUGUESE, DUTCH, CONQUESTS, FIGHTING factsanddetails.com

MALACCA SULTANATE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, PARAMESVARA factsanddetails.com

JAMES BROOKE AND MAKING NORTHERN BORNEO PART OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FIGHTING WITH BORNEO PIRATES factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BRITISH COLONIAL IN MALAYSIA: HILL STATIONS, CHINESE, INDIANS factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

EARLY KINGDOMS, EMPIRES AND THE ARRIVAL OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

How the British Gradually Took Moved Into Peninsular Malaysi

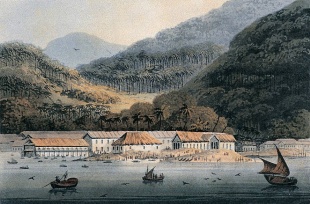

In 1786, the British East India Company laid the groundwork for British control of Malaya when Francis Light of the British East India Company, seeking a strategic trading post and naval base, secured the cession of the island of Penang from the sultan of Kedah. Penang is located off the west coast of Malaya, about 800 kilometers (500 miles) north of Singapore. In 1791, the Company obtained a small area on the mainland (known as Province Wellesley) opposite Penang by agreeing to pay the sultan an annual allowance. In 1800 Kedah ceded Province Wellesley to the British [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

English traders had been present in Malay waters since the 17th century. Before the mid-19th-century British interests in the region were predominantly economic, with little interest in territorial control. Already the most powerful coloniser in India, they were looking towards southeast Asia for new resources. The growth of the China trade in British ships increased the Company’s desire for bases in the region. Various islands were used for this purpose, but the first permanent acquisition was Penang.

The British founded Singapore in 1819 and formally acquired Malacca from the Dutch in 1824, although they had exercised control there since 1795. Penang, Malacca, and Singapore were placed under a joint administration known as the Straits Settlements. At the same time, Siam was extending its influence southward. In 1816 Siam compelled Kedah to invade Perak and forced Perak to acknowledge Siamese suzerainty. Siam invaded Kedah outright in 1821 and exiled its sultan. The Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1821 recognized Siamese control over Kedah while leaving the status of Perak, Kelantan, and Terengganu unresolved. Kedah’s sultan was restored in 1841, but Perlis was separated from Kedah and placed under Siamese protection. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty and British Control of Malaya

In 1824 the British hegemony in Malaya was formalised by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, which divided the Malay archipelago between Britain and the Netherlands. The Dutch evacuated Malacca and renounced all interest in Malaya, while the British recognized Dutch rule over the rest of the East Indies. By 1826 the British controlled Penang, Malacca, Singapore and the island of Labuan, which they established as the crown colony of the Straits Settlements, administered first under the East India Company until 1867, when they were transferred to the Colonial Office in London.

In 1795, during the Napoleonic Wars, the British with the consent of the Netherlands occupied Dutch Malacca to forestall possible French interest in the area. When Malacca was handed back to the Dutch in 1815, the British governor, Stamford Raffles, looked for an alternative base, and in 1819 he acquired Singapore from the Sultan of Johor. The exchange of the British colony of Bencoolen for Malacca with the Dutch left the British as the sole colonial power on the peninsula. The territories of the British were set up as free ports, attempting to break the monopoly held by other colonial powers as the time, and making them large bases of trade. They allowed Britain to control all trade through the straits of Malacca. British influence was increased by Malayan fears of Siamese expansionism, to which Britain made a useful counterweight. During the 19th century the Malay Sultans aligned themselves the British Empire, due to the benefits of associations with the British and the belief in superior British civilisation.

According to UNESCO: In 1795-1818, during the Napoleonic wars in Europe, Melaka came into British hands. By then Penang/George Town had been in existence for some time and as its rival, it was initially ordered to level Melaka. The fort was demolished, only the gate is left, but then the destruction was stopped. A few years later, in 1824, Melaka was finally brought under British administration. George Town was founded in 1786 by the British. Unlike the Portuguese and the Dutch they exercised a policy of free trade. People from all over the world were encouraged to settle in the new town and to produce export crops. To administer the island, a Presidency was set up under the jurisdiction of the East India Company in Bengal and in 1826 it became part of the Straits Settlements together with Singapore and Melaka. [Source: UNESCO]

How Sarawak and Sabah in Northern Borneo Fell Into British Hands

Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei were once part of the Bruneian empire, and for centuries Borneo developed largely separately from Peninsular Malaysia due to limited European involvement. By the 19th century, northern Borneo was divided between the Sultanate of Brunei and the Sultan of Sulu, while the Dutch controlled the south. This changed in 1839 when James Brooke aided the Brunei sultan in suppressing a rebellion and was granted control of Sarawak, becoming its raja in 1841. The Brooke family ruled Sarawak as the independent “White Rajahs” for a century, expanding their territory at Brunei’s expense.

British involvement increased out of concern over regional stability and foreign rivalry. In 1888, Britain placed Sarawak, Brunei, and Sabah—then administered by the British North Borneo Company—under protection while controlling their foreign affairs. Sabah’s transfer, contested by the Philippines due to the Sultan of Sulu’s claims, and the establishment of British protectorates consolidated northern Borneo under British influence, distinct from Dutch-controlled southern Borneo. After World War II, Britain acquired Sarawak when the Brooke dynasty ended, and early 20th-century migration of Chinese and Indians significantly altered the region’s demographic makeup.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LATER BORNEO HISTORY: COLONIALISM, BRITAIN, DUTCH, MALAYSIA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

JAMES BROOKE AND MAKING NORTHERN BORNEO PART OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FIGHTING WITH BORNEO PIRATES factsanddetails.com

Britain Tightens Control with the Federated and Unfederated Malay States

Although initially reluctant to expand their commitments in Malaya, British involvement deepened in the latter half of the nineteenth century as unrest spread across the peninsula. Conflicts erupted between Chinese tin miners and Malays, Siamese incursions into northern Malay states took place, civil wars broke out among Malay rulers, and piracy increased along the west coast. These disturbances endangered British commercial interests, particularly in tin. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Merchants appealed to Britain to restore order, while British officials grew concerned about rising Dutch, French, and German interest in the region. In response, Britain concluded treaties with Perak, Selangor, Pahang, and the states that later formed Negeri Sembilan. Under these agreements, a British “resident” was appointed to advise each sultan and oversee administration, while the ruler received a stipend. The Pangkor Treaty of 1874 with Perak became the model for later arrangements.

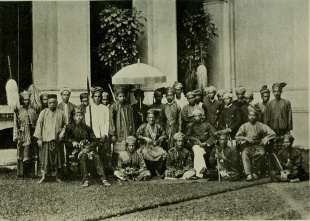

Under the Pangkor Treaty of 1874, Britain adopted a system of indirect rule that laid the foundations of a centralized colonial state. the British recognized a new sultan of Perak in return for his acceptance of a British “resident,” whose advice had to be followed on all matters except religion and custom. Similar arrangements were later imposed on other tin-producing states, which became known as the Federated Malay States and were formally united in 1896 under a British resident-general. . Although Malay rulers retained ceremonial roles, real authority rested with British officials. Other Malay states were governed under looser arrangements. Johor’s ruler, Sultan Abu Bakar, maintained close personal ties with Queen Victoria and preserved autonomy until 1914, when his successor accepted a British adviser. [Source: Wikipedia]

The northern states of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu, long under nominal Siamese control, came under British influence following the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. Their rulers rejected federation but accepted British advisers, who relied on persuasion rather than direct authority. By 1914, the Malay Peninsula consisted of ten political units: the Straits Settlements, four Federated Malay States, and five Unfederated Malay States. The areas under the most direct British control developed rapidly and became leading global producers of tin and, later, rubber.

British Rule in Colonial Malaya

By 1910, the framework of British rule in Malaya was firmly established. The Straits Settlements were administered as a Crown Colony under a British governor reporting to the Colonial Office in London. About half of their population was Chinese, but all residents, regardless of ethnicity, were British subjects. Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang formed the Federated Malay States; although nominally independent, they were placed under a Resident-General in 1895 and were effectively British colonies. The remaining states—Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu—were known as the Unfederated Malay States and retained slightly more autonomy, though British Residents still exercised decisive influence. Johore, Britain’s closest ally in Malaya, was granted a written constitution allowing the Sultan to appoint his own cabinet, but in practice he generally consulted British authorities before acting.

Using divide and rule tactics, the British encouraged rivalries between Malaysia's different ethnic groups and between the sultans. In the early days of the British presence the sultans still held a lot of power. As time went on this power was reduced and Britain took firm control of the mainland.

The Malay Peninsula under British rule before World War II, future Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad wrote was “divided into many different Malay states, and each state had its own treaty with the British. The treaties were for British ‘protection,’ it was said, not colonization. The British were not too repressive...Although the British actually controlled the administration fully, they managed to give the impression that locals had status and authority. The Malaysia sultans were called ‘the rulers’ by the British, although they were never really given any power to ‘rule.’

Lasting British influence includes a parliamentary democracy with a largely ceremonial monarch. Mahathir Mohamad wrote: “The British did not send a ‘governor’ to our country, but an official they called a ‘British Advisor.’ In reality, however, his ‘advise’ had to strictly followed....The British were extremely clever at this form of semi-colonial rule: they would call things by one name, but in reality do quite another thing. What we did get from them was a well-organized administration and a fairly well-developed infrastructure. What we also got, however, was a psychological burden, was the belief that only Europeans could govern our country effectively...Most Asians felt inferior to European colonizers.

Transition to Capitalist Production in Malaysia

During the late nineteenth century, Malaya’s economy took on many of its modern characteristics. Tin production expanded rapidly with the introduction of modern mining techniques, and rubber cultivation was introduced on a large scale, relying heavily on imported Indian labor. Malaya soon became one of the world’s leading rubber producers. Its economic importance and strategic location made it a prime wartime target by the Japanese in World War II. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

The nineteenth century saw a dramatic expansion of global trade. Between 1815 and 1914, world trade grew at an average annual rate of 4–5 percent, compared with roughly 1 percent during the previous century. This surge was driven by the Industrial Revolution in the West, which introduced large-scale factory production made possible by technological innovation. These advances were accompanied by major improvements in transportation and communication—such as railways, steamships, automobiles, trucks, international canals (the Suez Canal in 1869 and the Panama Canal in 1914), and telegraph networks—that significantly reduced the cost and time required for long-distance trade. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia]

Industrializing nations required steadily increasing supplies of raw materials and food to support their expanding populations. Regions such as Malaysia, with abundant virgin land and close access to major trade routes, were well positioned to meet this demand. What these regions lacked, however, was sufficient capital and wage labor. Both shortages were largely filled through foreign sources.

As British influence expanded and brought greater political stability, large numbers of Chinese migrants arrived, with Singapore rapidly emerging as the principal entry point. Most migrants arrived with limited resources, but those who accumulated wealth through trade—including the opium trade—reinvested their profits in agricultural and mining ventures, particularly on the Malay Peninsula. Export crops such as pepper, gambier, tapioca, sugar, and coffee were produced for Asian markets, especially China, and increasingly for Western markets after 1850 as Britain adopted free-trade policies. These crops were labor-intensive rather than capital-intensive and, in some cases, quickly depleted soil fertility, necessitating periodic shifts to new areas of virgin land (Jackson, 1968).

Tin in Malaysia

John H. Drabble of the University of Sydney wrote: “Besides ample land, the Malay Peninsula also contained substantial deposits of tin. International demand for tin rose progressively in the nineteenth century due to the discovery of a more efficient method for producing tinplate (for canned food). At the same time deposits in major suppliers such as Cornwall (England) had been largely worked out, thus opening an opportunity for new producers. Traditionally tin had been mined by Malays from ore deposits close to the surface. Difficulties with flooding limited the depth of mining; furthermore their activity was seasonal. From the 1840s the discovery of large deposits in the Peninsula states of Perak and Selangor attracted large numbers of Chinese migrants who dominated the industry in the nineteenth century bringing new technology which improved ore recovery and water control, facilitating mining to greater depths. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

“By the end of the century Malayan tin exports (at approximately 52,000 metric tons) supplied just over half the world output. Singapore was a major center for smelting (refining) the ore into ingots. Tin mining also attracted attention from European, mainly British, investors who again introduced new technology – such as high-pressure hoses to wash out the ore, the steam pump and, from 1912, the bucket dredge floating in its own pond, which could operate to even deeper levels. These innovations required substantial capital for which the chosen vehicle was the public joint stock company, usually registered in Britain. Since no major new ore deposits were found, the emphasis was on increased efficiency in production. European operators, again employing mostly Chinese wage labor, enjoyed a technical advantage here and by 1929 accounted for 61 percent of Malayan output (Wong Lin Ken, 1965; Yip Yat Hoong, 1969). +\

Rubber Plantations in Asia

Rubber plantation agriculture was introduced to Southeast Asia in the 19th century. It revolutionized parts of the economy there. Today, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand produce three quarters of the world's rubber as well as three quarters of the world's palm oil and large percentage of the coffee and cocoa crops.

Rubber trees were identified and studied in the Amazon by Sir Henry Wickham, who shipped 70,000 seedling to Kew Garden in 1876. Seedlings were sent from there to Sri Lanka and Malaysia.

In 1823 the Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh discovered that rubber dissolved in the coal-tar and the mixture could be applied to cloth. He invented the raincoat. In 1844, Charles Goodyear, an American hardware merchant, patented the vulcanization process, in which sulfur is added to rubber so that it doesn't melt in heat and go brittle in cold. Goodyear discovered the process after eight years of trying to make a useful rubber when he accidently dropped a mixture of India rubber and sulfur onto a hot stove. The rubber melted and bonded with the sulfur, producing vulcanized rubber. The air-inflated pneumatic rubber tires was invented by Scotsman J.B. Dunlop in 1887. After that the rubber industry really took off.

The rubber industry got off to a slow start in Asia and didn’t really blossom until Brazilian rubber merchants tried to corner the market in 1905 and raised rubber prices high enough so that plantation owners in Asia could maker a profit. By 1915, three million acres of land was devoted to rubber in the Asia.

Latex could be grown much more efficiently and profitably on plantations in Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries than in Brazil. Asian latex was much quality than wild latex form Brazil, which was filled with impurities. The British made a fortune with massive rubber plantations in Malaysia. Today, the United States alone imports over a billion dollars worth of the stuff every year.

Impact of Rubber on Malaysia

John H. Drabble of the University of Sydney wrote: “While tin mining brought considerable prosperity, it was a non-renewable resource. In the early twentieth century it was the agricultural sector which came to the forefront. The crops mentioned previously had boomed briefly but were hard pressed to survive severe price swings and the pests and diseases that were endemic in tropical agriculture. The cultivation of rubber-yielding trees became commercially attractive as a raw material for new industries in the West, notably for tires for the booming automobile industry especially in the U.S. Previously rubber had come from scattered trees growing wild in the jungles of South America with production only expandable at rising marginal costs. Cultivation on estates generated economies of scale. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

In the 1870s the British government organized the transport of specimens of the tree Hevea Brasiliensis from Brazil to colonies in the East, notably Ceylon and Singapore. There the trees flourished and after initial hesitancy over the five years needed for the trees to reach productive age, planters Chinese and European rushed to invest. The boom reached vast proportions as the rubber price reached record heights in 1910. Average values fell thereafter but investors were heavily committed and planting continued (also in the neighboring Netherlands Indies [Indonesia]). By 1921 the rubber acreage in Malaysia (mostly in the Peninsula) had reached 935 000 hectares (about 1.34 million acres) or some 55 percent of the total in South and Southeast Asia while output stood at 50 percent of world production.

“As a result of this boom, rubber quickly surpassed tin as Malaysia's main export product, a position that it was to hold until 1980. A distinctive feature of the industry was that the technology of extracting the rubber latex from the trees (called tapping) by an incision with a special knife, and its manufacture into various grades of sheet known as raw or plantation rubber, was easily adopted by a wide range of producers. The larger estates, mainly British-owned, were financed (as in the case of tin mining) through British-registered public joint stock companies. For example, between 1903 and 1912 some 260 companies were registered to operate in Malaya. Chinese planters for the most part preferred to form private partnerships to operate estates which were on average smaller. Finally, there were the smallholdings (under 40 hectares or 100 acres) of which those at the lower end of the range (2 hectares/5 acres or less) were predominantly owned by indigenous Malays who found growing and selling rubber more profitable than subsistence (rice) farming. These smallholders did not need much capital since their equipment was rudimentary and labor came either from within their family or in the form of share-tappers who received a proportion (say 50 percent) of the output. In Malaya in 1921 roughly 60 percent of the planted area was estates (75 percent European-owned) and 40 percent smallholdings (Drabble, 1991, 1). +\

“The workforce for the estates consisted of migrants. British estates depended mainly on migrants from India, brought in under government auspices with fares paid and accommodation provided. Chinese business looked to the "coolie trade" from South China, with expenses advanced that migrants had subsequently to pay off. The flow of immigration was directly related to economic conditions in Malaysia. For example arrivals of Indians averaged 61 000 a year between 1900 and 1920. Substantial numbers also came from the Netherlands Indies. +\

“Thus far, most capitalist enterprise was located in Malaya. Sarawak and British North Borneo had a similar range of mining and agricultural industries in the 19th century. However, their geographical location slightly away from the main trade route and the rugged internal terrain costly for transport made them less attractive to foreign investment. However, the discovery of oil by a subsidiary of Royal Dutch-Shell starting production from 1907 put Sarawak more prominently in the business of exports. As in Malaya, the labor force came largely from immigrants from China and to a lesser extent Java. The growth in production for export in Malaysia was facilitated by development of an infrastructure of roads, railways, ports (e.g. Penang, Singapore) and telecommunications under the auspices of the colonial governments, though again this was considerably more advanced in Malaya (Amarjit Kaur, 1985, 1998) +\

Malaysian Economy Before World War II

By the late nineteenth century, stable forms of government had emerged in Malaysia, and its economy and culture began to assume characteristics that would endure for decades. In the late 1800s, copious deposits of tin ore were discovered in the northwestern state of Perak, and this led to substantial growth in mining and the creation of administrative and transportation infrastructure to service the tin industry, which in turn enabled the growth of other industries along the west coast, such as rubber plantations. This early export diversification helped the economy respond to changing international prices for primary commodities and generally aided economic growth. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Before World War II, the global economy was broadly divided between industrialized countries in the Northern Hemisphere and raw-material producers in the Southern Hemisphere. This arrangement, known as the Old International Division of Labor, placed Malaya firmly in the role of exporting primary commodities such as tin, rubber, timber, and oil, while importing manufactured goods. Because little processing was done locally, most of the profits from these products went to foreign manufacturers. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

Malaysia therefore depended heavily on export earnings to maintain living standards. Rice production met only about 40 percent of domestic needs, so imports—mainly from Burma and Thailand—were essential. When commodity prices were high, export income supported strong economic growth and rising incomes. Although no official national income data exist for this period, estimates suggest that by the late 1920s Malaya had one of the highest GDP per person levels in Southeast and East Asia.

However, this export-dependent economy was highly vulnerable to global economic swings. After World War I, a brief depression occurred from 1919 to 1922. This was followed by strong growth in the mid-1920s, and then the Great Depression of 1929–1932. As industrial output collapsed in countries like the United States, demand for raw materials fell sharply. Rubber prices in 1932 dropped to about one-hundredth of their 1910 peak. Between 1929 and 1932, export earnings fell dramatically across Malaya, Sarawak, and North Borneo. Imports also declined steeply. Plantations laid off workers, many of whom returned to their home countries due to the lack of social welfare. Small farmers suffered falling incomes and many lost their land after being unable to repay high-interest loans.

In response, the colonial government introduced measures to stabilize commodity prices. Rubber exports were restricted under two schemes between 1922–1928 and 1934–1941, while tin exports were limited from 1931 to 1941. These policies succeeded in raising world prices, but they were criticized for favoring European producers over Asian ones. They also helped lock the economy into primary production and discouraged diversification into manufacturing.

Before World War II, Malaysia had very little industrial development. Most secondary industries were linked to processing tin and rubber or producing basic goods for the local market, such as food, beverages, cigarettes, and building materials. Much of this activity was Chinese-owned and concentrated in Singapore. Several factors limited industrial growth, including the small domestic market, relatively high wages, and a commercial culture dominated by British trading firms. Above all, the dominance of primary exports reduced incentives to invest in manufacturing. When commodity prices were high, diversification seemed unnecessary; when prices fell, capital and demand disappeared. As one historian has noted, there was effectively never a favorable moment to begin industrialization in prewar Malaya.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026