HISTORY OF MALACCA

Malacca — near the southern tip of Peninsular Malaysia — is a charming town with a rich history. Strategically located on the Malacca Straits, a vital waterway between India, the Spice Islands, China and Europe, it was once one of the most important ports in the world. According to one old saying, "He who is the lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice."

By the 15th century the predominate power in Indonesia was Malacca (Melaka), the trading kingdom based on the Malay peninsula. The Melaka kingdom controlled the strategic shipping lanes of the Malacca Straits and important commercial ports on northern Java. By the 16th century Melaka was the supreme power in Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

Part of maritime Silk Road, Malacca was founded in 1402 by Paramesvara, a prince who fled from Sumatra and established a port, which attracted trading ships from as far away as China, India and the islands near New Guinea. These ships carried things like sandalwood, pearls, porcelain, silk, gold, tin, and bird-of-paradise feathers as well as profitable cargos of cloves, pepper, cinnamon, mace, and nutmeg from the Spice Islands in what is now eastern Indonesia.

The Portuguese grabbed Malacca away from the Sumatran-Malay princes after a bloody six week battle in 1511. Portugal grew rich on Asian trade, which caught the attentions of other emerging European powers. In 1641, the Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch, who in turn were ousted by the British in 1795. At one time 86 languages were spoken in Malacca.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MALACCA: COLONIAL SIGHTS, HISTORIC SITES, TOURISM, MUSEUMS factsanddetails.com

EARLY KINGDOMS, EMPIRES AND THE ARRIVAL OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS IN MALAYSIA: PORTUGUESE, DUTCH, CONQUESTS, FIGHTING factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

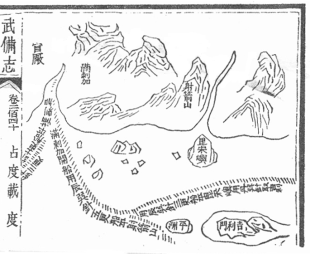

Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is a narrow strait of water that divides the Indonesian island of Sumatra from Malaysia and Singapore. It is also one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. The 890-kilometer-long waterway carries one third of the world’s trade and one half of the world’s oil supply. Carrying more ships everyday than the Panama and Suez Canals combined, its strategic importance can not be underestimated. The strait doesn't lie in international waters but is located in the territorial waters of Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and these countries are responsible for patrolling it.

More than 60,000 ships — equal to half the world's merchant fleet — carrying half the world's oil and 40 percent of its commerce pass through the Malacca Strait. The ship range from mammoth supertankers as large as city skyscrapers to tugs and barges. Lots of tankers going between the Persian Gulf and East Asia pass through the strait. As parts of the strait are only one kilometer wide ships have to sail at low speed.

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: For centuries, this sliver of ocean has captivated seamen, offering the most direct route between India and China, along with a bounty of resources, including spices, rubber, mahogany, and tin. But it is a watery kingdom unto itself, harboring hundreds of rivers that feed into the channel, miles of swampy shoreline, and a vast constellation of tiny islands, reefs, and shoals. Its early inhabitants learned to lead amphibian lives, building their villages over water and devising specialized boats for fishing, trading, and warfare. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, October 2007]

Patrick Winn wrote in Global Post, “The Strait of Malacca is a natural paradise for seafaring bandits. Imagine an aquatic highway flowing between two marshy coasts. One shoreline belongs to Malaysia, the other to Indonesia. Each offers a maze of jungly hideaways: inlets and coves that favor pirates’ stealth vessels over slow, hulking ships. It's a narrow route running 550 miles, roughly the distance between Miami and Jamaica. This bottleneck is plied by one-third of the world's shipping trade. That's 50,000 ships per year — ferrying everything from iPads to Reeboks to half the planet's oil exports. Avoiding pirates by traveling fast is “practically impossible in the Strait of Malacca. The channel is simply too crowded and too shallow. Gigantic vessels are instead forced to churn through at slow speeds that invite pirates in fast-moving skiffs. (To save fuel, today's cargo ships often travel at about 14 miles per hour. That's slower than 19th-century sail boats.) [Source: Patrick Winn, GlobalPost, March 27, 2014]

Establishment of Malacca

Malacca was founded in 1402 by Paramesvara, a prince who fled from Sumatra and established a port which attracted trading ships from as far away as China, India and the islands near New Guinea. These ships carried sandalwood, pearls, porcelain, silk, gold, tin , bird-of-paradise feathers and spices such as cloves, mace and nutmeg from the Spice Islands in what is now eastern Indonesia. Malacca became an Islamic state after Prince Paramesvara converted to Islam. Malacca then became a major supply stop for ships traveling the trade routes between China and the Arab sultanates around the Persian Gulf.

Around 1390, Parameswara was forced to flee his homeland. He landed on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula with a loyal following of about a thousand men and survived for nearly a decade through piracy and control of local trade routes. At the time, Siam (modern Thailand) was the dominant regional power. By about 1403, Parameswara expelled Siamese forces from the area and established the settlement of Malacca. The name Malacca is often linked to the Arabic word malakut, meaning marketplace, reflecting the presence of Arab traders who had maintained commercial links in the region since as early as the eighth century. [Source: Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD wrote in the Encyclopedia of Islamic History]

Once established, Parameswara promoted peaceful trade, and Malacca rapidly grew into a prosperous international port. Muslim merchants dominated Indian Ocean commerce, with Arabic serving as the lingua franca of trade, while Islam was spreading across the Indonesian archipelago. Across the Strait of Malacca, the powerful Muslim kingdom of Pasai and the rising state of Aceh exerted growing influence. According to local tradition, around 1405 Parameswara embraced Islam, married a princess from Pasai, and adopted the name Sultan Iskander Shah—a story often portrayed in folklore as symbolizing the introduction of Islam to Malaya.

Malacca Sultanate

The commencement of the current Malay nation is often traced to the fifteenth-century establishment of Malacca (Malacca) on the peninsula’s west coast. Malacca’s founding is credited to the Srivijayan prince Sri Paramesvara, who fled his kingdom to avoid domination by rulers of the Majapahit kingdom.

Early Malaysian cities and states originated in the coast and then moved to interior. These traded expensively with Chinese traders, who began arrived in numbers in the 14th century. Groups such as the Acehese, the Bugis and the Mnangkabau fought for dominance over the peninsula.

Before colonization, Malaysia was ruled sultanas who ruled over fiefdoms. The largest and most powerful of these Malacca kingdom on the Malay peninsular that was dominant power 1400-1511. It vied with the Chinese and Thais for control of the region.

By the late fourteenth century, Malacca had become an important commercial power and cultural influence along the Strait of Malacca, largely as a result of its numerous advantages as a trading port and its commercial and military alliances with China and the Malay kingdom of Bintan, an island near Singapore and home of the Orang Laut. When Muzaffar Shah became Malacca’s ruler in 1444, he declared the kingdom a Muslim state, and Malacca’s growing commercial, military, and political influence helped spread the Islamic faith throughout the region.

In 2020, researchers excavating a site on Pulau Melaka, a man-made island off the coast of Malaysia, uncovered the remains of a centuries-old shipwreck marked by rectangular wooden fragments protruding from the ground. The wreck, dated to the 15th or 16th century — the Malaccan Sultane Period — is the first shipwreck discovered in reclaimed land in Malaysia and reflects a very different coastal landscape at the time of its sinking. Guided by ground-penetrating radar, archaeologists recovered 306 artifacts, including coins from Malaysia, China, and Portugal, as well as ceramic fragments, highlighting the region’s role as a major maritime trading hub along the Strait of Malacca. Further analysis is needed to determine the precise origins of the artifacts, and researchers have urged continued monitoring of the site to prevent damage or disturbance. [Source: Brendan Rascius, Miami Herald, April 13, 2024]

Prince Parameswara

The port of Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula was founded in 1402 by Parameswara, a Srivijaya prince fleeing Temasek (now Singapore), who was claimed in the Sejarah Melayu to be a descendant of Alexander the Great. Parameswara in particular sailed to Temasek to escape persecution. There he came under the protection of Temagi, a Malay chief from Patani who was appointed by the king of Siam as regent of Temasek. Within a few days, Parameswara killed Temagi and appointed himself regent. Some five years later he had to leave Temasek, due to threats from Siam. During this period, a Javanese fleet from Majapahit attacked Temasek. [Source: Wikipedia]

Parameswara headed north to found a new settlement. At Muar, Parameswara considered siting his new kingdom at either Biawak Busuk or at Kota Buruk. Finding that the Muar location was not suitable, he continued his journey northwards. Along the way, he reportedly visited Sening Ujong (former name of present-day Sungai Ujong) before reaching a fishing village at the mouth of the Bertam River (former name of the Malacca River), and founded what would become the Malacca Sultanate. Over time this developed into modern-day Malacca Town. According to the Malay Annals, here Parameswara saw a mouse deer outwitting a dog resting under a Malacca tree. Taking this as a good omen, he decided to establish a kingdom called Malacca. He built and improved facilities for trade. The Malacca Sultanate is commonly considered the first independent state in the peninsula.

At the time of Malacca's founding, the emperor of Ming Dynasty China was sending out fleets of ships to expand trade. Admiral Zheng He called at Malacca and brought Parameswara with him on his return to China, a recognition of his position as legitimate ruler of Malacca. In exchange for regular tribute, the Chinese emperor offered Malacca protection from the constant threat of a Siamese attack. The Chinese and Indians who settled in the Malay Peninsula before and during this period are the ancestors of today's Baba-Nyonya and Chetti community. According to one theory, Parameswara became a Muslim when he married a Princess of Pasai and he took the fashionable Persian title "Shah", calling himself Iskandar Shah. Chinese chronicles mention that in 1414, the son of the first ruler of Malacca visited the Ming emperor to inform them that his father had died. Parameswara's son was then officially recognised as the second ruler of Malacca by the Chinese Emperor and styled Raja Sri Rama Vikrama, Raja of Parameswara of Temasek and Malacca and he was known to his Muslim subjects as Sultan Sri Iskandar Zulkarnain Shah or Sultan Megat Iskandar Shah. He ruled Malacca from 1414 to 1424. Through the influence of Indian Muslims and, to a lesser extent, Hui people from China, Islam became increasingly common during the 15th century.

Early Years of the Malacca Sultanate

In a bid to attract East–West commerce as well as regional trade and shipping, Parameshwara provided excellent facilities for merchants and mariners from India, China, Java, Champa, Pegu (Lower Burma), and Arabia. Many of these traders needed to remain in port for several months each year until the monsoons subsided. In the process, Parameshwara and the dynasty he founded established a lasting tradition of a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society, one that thrived on coexistence and cooperation within distinct quarters of the city-state. [Source: World EducD. R. Sar Desai, World Educ ation Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Malacca’s fortunes continued to rise. In 1405, the Chinese emperor Yongle (r. 1403–1424) dispatched an envoy led by Admiral Yin Qing to offer trade and diplomatic relations, an alliance welcomed by Malacca as pressure from Siam increased. These contacts deepened in 1409 when the famed Chinese admiral Zheng He (Cheng Ho) —himself a Muslim—visited Malacca with a vast fleet during his voyages across the Indian Ocean. Zheng He carried an imperial invitation for Sultan Iskander Shah to visit China.

In 1411, Sultan Iskander Shah traveled to China, where he was warmly received and presented with silk, precious stones, horses, gold, and silver. Malacca was granted favored trading status and entered into mutual defense arrangements with China, helping to deter further Siamese incursions. After his return, Sultan Iskander Shah ruled as a patron of Islamic scholarship, inviting learned men from distant centers such as Mecca and encouraging the spread of Islam. Under his leadership, Malacca became both a major hub of international commerce and a center of Islamic learning.

Sultan Iskander Shah died in 1424. His tomb no longer survives, reportedly destroyed after the Portuguese conquest of Malacca in 1511. Nevertheless, his legacy endured: he transformed Malacca into one of the most important trading and cultural centers of Southeast Asia and laid the foundations for the Islamization of the Malay Peninsula.

Power and Influence of the Malacca Sultanate

After an initial period paying tribute to the Ayutthaya, the Malacca rapidly assumed the place previously held by Srivijaya, establishing independent relations with China, and exploiting its position dominating the Straits to control the China-India maritime trade, which became increasingly important when the Mongol conquests closed the overland route between China and the west.

The arrival of Chinese admiral Zheng He came with promises to the locals of protection from the Siamese encroaching from the north. With Chinese support, the power of Malacca extended to include most of the Malay Peninsula. Islam arrived in Malacca around this time and soon spread through Malaya.

Within a few years of its establishment, Malacca officially adopted Islam. Parameswara became a Muslim, and due to the fact Malacca was under a Muslim Prince the conversion of Malays to Islam accelerated in the 15th century. The political power of the Malaccan Sultanate helped Islam’s rapid spread through the archipelago.

Malacca was an important commercial centre during this time, attracting trade from around the region. By the start of the 16th century, with Malaccan Sultanate in the Malay peninsula and parts of Sumatra, the Sultanate of Demak in Java, and other kingdoms around the Malay archipelago increasingly converting to Islam, it had become the dominant religion among Malays, and reached as far as the modern day Philippines, leaving Bali as an isolated outpost of Hinduism today.

Malacca's reign lasted little more than a century, but during this time became the established centre of Malay culture. Most future Malay states originated from this period. Malacca became a cultural centre, creating the matrix of the modern Malay culture: a blend of indigenous Malay and imported Indian, Chinese and Islamic elements. Malacca's fashions in literature, art, music, dance and dress, and the ornate titles of its royal court, came to be seen as the standard for all ethnic Malays. The court of Malacca also gave great prestige to the Malay language, which had originally evolved in Sumatra and been brought to Malacca at the time of its foundation. In time Malay came to be the official language of all the Malaysian states, although local languages survived in many places. After the fall of Malacca, the Sultanate of Brunei became the major centre of Islam.

Portuguese Take Over Malacca

In 1511, about 50 years after the Portuguese seaman Vasco de Gama rounded Cape of Good Hope and reached India, the Portuguese grabbed Malacca away from the Malays after a bloody six week battle in 1511. Even though the Malay sultan occupied a well-protected fortified place, their bows, arrows, lances, spears and battle elephants were no match for the Portuguese canons and primitive muskets.

The Portuguese set up a trading post in Malacca, providing a key supply station and trading center for spices coming the East Indies and porcelain, silk and treasures from China. Portugal grew rich on Asian trade and fulfilled the saying: "Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice."

Magellan stopped in Malacca before his historical trip around the world. The Spanish missionary St. Francis Xavier confounded the Jesuit order and traveled 38,000 miles spreading the word of the Gospel. St Paul's church in the Portuguese quarter of Malacca, Malaysia is where Francis Xavier was displayed in an open coffin for ten months before he was buried in Goa.

St. Paul's Church on a hill in Malacca, according to Smithsonian magazine, is “where St. Francis Xavier is said to have denounced dissolute parishioners in the loth century for turning Portugal's most important colony into "the Babylon of the East." At the hill's bottom was evidence of the Portuguese population's comeuppance-the 18th-century Christ Church, whose floor the Dutch paved with the tombstones of their rivals. The most evocative symbol of the city's storied past could be found at the river's mouth: a replica of the Fiordo Mar, the Portuguese carrack that set sail for Goa with tons of gold and jewels looted from the Malacca sultanate- only to founder off Sumatra in 1511.”

Australia marine archaeologist Michael Flecker heads a marine archaeology consulting firm called Maritime Explorations. He has worked with Malaysia's Department of Museums to explore a Portuguese shipwreck in the Malacca Straits.

Malaysia and the Sultanates of Johor and Aceh

After the fall of Malacca to Portugal, the Johor Sultanate and the Sultanate of Aceh on northern Sumatra moved to fill in the power vacuum left behind. The three powers struggled to dominate the Malay peninsula and the surrounding islands. Johor founded in the wake of Malacca's conquest grew powerful enough to rival the Portuguese, although it was never able to recapture the city. Instead it expanded in other directions, building in 130 years one of the largest Malay states. In this time the numerous attempts to recapture Malacca led to a strong backlash from the Portuguese, whose raids even reached Johor's capital of Johor Lama in 1587.

In 1607, the Sultanate of Aceh rose as the powerful and wealthiest state in Malay archipelago. Under Iskandar Muda reign, he extended the sultanate's control over a number of Malay states. A notable conquest was Perak, a tin-producing state on the Peninsula. The strength of his formidable fleet was brought to an end with a disastrous campaign against Malacca in 1629, when the combined Portuguese and Johor forces managed to destroy all his ships and 19,000 troops according to Portuguese account. Aceh forces was not destroyed, however, as Aceh was able to conquer Kedah within the same year and taking many of its citizens to Aceh. The Sultan's son in law, Iskandar Thani, former prince of Pahang later became his successor. The conflict over control of the straits went on until 1641, when the Dutch (allied to Johor) gained control of Malacca.

See Separate Article: ACEH HISTORY: TRADE, ISLAM, KINGDOMS, ESCAPING COLONIALISM factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Malaysia Tourism websites, Malaysia government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated in January 2026