EARLY EUROPEAN PRESENCE IN MALAYA

Near the beginning of the sixteenth century, European powers became interested in Malacca’s trade and the opportunity to spread Christianity in Asia. The closing of the overland route from Asia to Europe by the Ottoman Empire and the claim towards trade monopoly with India and south-east Asia by Arab traders, led European powers to look for a maritime route. Malacca’s wealth and prosperity attracted European interest and it was taken over by the Portuguese in 1511, then the Dutch in 1641 and the British in 1795.

Attracted by the region's lucrative trade opportunities in Southeast Asia and what is now Indonesia, particularly the spice trade, a Portuguese fleet seized control of Malacca in 1511, marking the onset of European expansion in Southeast Asia. The Dutch ousted the Portuguese from Malacca in 1641. In 1786, the British obtained the island of Penang and, with Dutch acquiescence, temporarily controlled Malacca from 1795 to 1818 to prevent it from falling to the French during the Napoleonic Wars. Through the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, the British gained lasting possession of Malacca from the Dutch in exchange for territory on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale 2008]

Malaysia has a long history as a source of internationally valued exports. From the early centuries AD, the region was known for gold, tin, and exotic products such as bird feathers, edible bird’s nests, aromatic woods, and tree resins. Its commercial importance was reinforced by its strategic position along maritime trade routes linking the Indian Ocean and East Asia. Arab, Indian, and Chinese merchants regularly visited and settled in port cities such as Malacca, founded around 1402 as one of the earliest Malay sultanates and a major center of regional and international trade. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MALACCA SULTANATE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, PARAMESVARA factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

EARLY KINGDOMS, EMPIRES AND THE ARRIVAL OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Fall of Malacca to the Portuguese and Its Consequences

In 1511, Portugal under Afonso de Albuquerque led an expedition to Malaya which seized Malacca with the intent of using it as a base for activities in southeast Asia and controlling the Strait of Malacca.. This was the first colonial claim on what is now Malaysia. At the time, the Malaccan Sultanate fell to Portugal in 1511 it was at the height of its glory and power and center of a large amount of trade activity. The Portuguese arrival incited trading rivalries and violent attacks on foreign vessels, causing larger ships to avoid the area in favor of safer waters elsewhere. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008.]

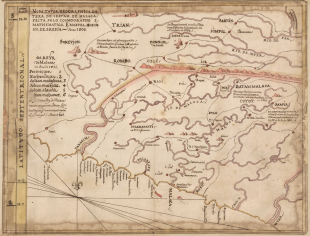

After the Portuguese captured Malacca in 1511, its sultan fled first to Pahang, then to Johor, and finally to the Riau Archipelago. One of his sons became the first sultan of Perak. Both Johor and Aceh in Sumatra made unsuccessful attacks on Malacca. Aceh and Johor also fought each other. The main issue in these struggles was control of trade through the Strait of Malacca. North of Malacca, Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu became nominal subjects of Siam. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Portuguese efforts to establish a trade monopoly were thwarted by military raids conducted by Malacca’s ruler Mahmud Shah and by his sons’ kingdoms, particularly Johor. Throughout the sixteenth century, Portugal, Johor, and Aceh (in Indonesia) variously fought and allied with one another in order to establish a trade monopoly in the region. By 1641, the Dutch had entered the fray, and an alliance with Johor helped the Dutch defeat the Portuguese and assume control of Malacca. [Source: Library of Congress, 2006]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Portuguese in Malaysia

In 1511, about 50 years after the Portuguese seaman Vasco de Gama rounded Cape of Good Hope and reached India, the Portuguese grabbed Malacca away from the Malays after a bloody six week battle in 1511. Even though the Malay sultan occupied a well-protected fortified place, their bows, arrows, lances, spears and battle elephants were no match for the Portuguese canons and primitive muskets.

The Portuguese set up a trading post in Malacca, providing a key supply station and trading center for spices coming the East Indies and porcelain, silk and treasures from China. Portugal grew rich on Asian trade and fulfilled the saying: "Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice."

Magellan stopped in Malacca before his historical trip around the world. The Spanish missionary St. Francis Xavier confounded the Jesuit order and traveled 38,000 miles spreading the word of the Gospel. St Paul's church in the Portuguese quarter of Malacca, Malaysia is where Francis Xavier was displayed in an open coffin for ten months before he was buried in Goa.

St. Paul's Church on a hill in Malacca, according to Smithsonian magazine, is “where St. Francis Xavier is said to have denounced dissolute parishioners in the loth century for turning Portugal's most important colony into "the Babylon of the East." At the hill's bottom was evidence of the Portuguese population's comeuppance-the 18th-century Christ Church, whose floor the Dutch paved with the tombstones of their rivals. The most evocative symbol of the city's storied past could be found at the river's mouth: a replica of the Fiordo Mar, the Portuguese carrack that set sail for Goa with tons of gold and jewels looted from the Malacca sultanate- only to founder off Sumatra in 1511.”

Australia marine archaeologist Michael Flecker heads a marine archaeology consulting firm called Maritime Explorations. He has worked with Malaysia's Department of Museums to explore a Portuguese shipwreck in the Malacca Straits.

Rivalry Between European Powers in Malaya

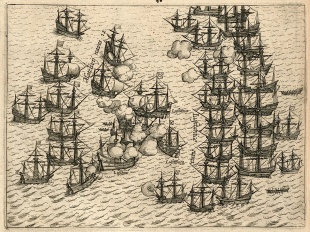

The Portuguese capture of Malacca in 1511 was followed by competition between the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the English East India Company (EIC) for control of the spice trade.

By the late 16th century the tin mines of northern Malaya had been discovered by European traders, and Perak grew wealthy on the proceeds of tin exports. Portuguese influence was strong, as they aggressively tried to convert the population of Malacca to Catholicism. In 1571 the Spanish captured Manila and established a colony in the Philippines, sharply reducing the Sultanate of Brunei's power. Stained ruin of a stone building, showing a central arch, flanked by two columns, with a stone relief above the arch, also flanked by two columns, and a second free-standing arch perched on the very top of the ruin.

By the late eighteenth century, the VOC dominated the Indonesian archipelago, while the EIC established key bases in Malaysia at Penang (1786), Singapore (1819), and Malacca (1824). These ports became major hubs for trade with China and stepping stones for British territorial expansion into the Malay Peninsula from the late nineteenth century and into northwest Borneo. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia ]

Dutch Take Control of Malaysia

In the early 17th century the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC ) was established and set up trading bases in Southeast Asia. By 1619, they had established themselves in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta). During this time the Dutch were at war with Spain, who obtained the Portuguese Empire due to the Iberian Union.

The Dutch expanded across what is now Indonesia. They formed an alliance with Johor and together they pushed the Portuguese out of Malacca in 1641 after a six-month siege. Backed by the Dutch, Johore established a loose hegemony over the Malay states, except Perak, which was able to play off Johore against the Siamese to the north and retain its independence. The Dutch did not interfere in local matters in Malacca, but at the same time diverted most trade to its colonies on Java. [Source: Wikipedia]

Another power entered the complicated Malay landscape in the late 17th century when the Bugis people from Sulawesi began settling in Selangor on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Pressured economically by the Dutch, the Bugis traded tin in the area. In 1721, the Bugis captured Johor and Riau and maintained control there for about a century, although the Johor sultanate was permitted to remain, despite a few interruptions. The Bugis were also active in Perak and Kedah. Earlier, in the 15th and 16th centuries, another Malay people, the Minangkabaus from Sumatra, had peacefully settled inland. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Dutch and Bugis in Malaysia

After the Dutch captured Malacca from the Portuguese in 1641, they controlled the port and dominated the spice trade of the Maluku Islands for the next 150 years. The Malay Peninsula, prized for its natural resources, was politically fragmented, and the weakness of its coastal states encouraged migration by the Bugis, who were fleeing Dutch expansion in Sulawesi. The Bugis established settlements across the peninsula and increasingly challenged Dutch commercial interests. Following the assassination of the last sultan of the old Malacca royal line in 1699, they seized control of Johor and expanded their influence into Kedah, Perak, and Selangor. At the same time, Minangkabau migrants from central Sumatra settled in Malaya and eventually founded the state of Negeri Sembilan. The decline of Johor created a power vacuum that allowed the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya to impose suzerainty over the northern Malay states of Kedah, Kelantan, Patani, Perlis, and Terengganu, while Perak emerged as the leading Malay state. [Source: Wikipedia]

During the eighteenth century, Malaya’s economic importance to Europe increased rapidly. The expanding tea trade between China and Britain sharply raised demand for Malayan tin, used to line tea chests, while Malayan pepper enjoyed a strong reputation in Europe and gold was mined in Kelantan and Pahang. The growth of tin and gold mining drew waves of foreign settlers—initially Arabs and Indians, and later large numbers of Chinese—who settled in urban centers and came to dominate commerce. This pattern entrenched a social structure in which rural Malay communities increasingly fell under the economic control of wealthy immigrant groups, beyond the effective authority of the Malay sultans.

Political fragmentation and competition for resources marked much of the eighteenth-century Malay world. In western Malaya, long-established migrant groups such as the Bugis and Minangkabau frequently clashed, with the Bugis emerging dominant by 1740 until their defeat by a Johor–Dutch alliance in 1784. In the east, Thai kingdoms repeatedly intervened in and ruled Malay states from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Meanwhile, Dutch trade monopolies fostered widespread smuggling, and piracy became endemic. Elite anak raja (sons of rulers) often supported piracy as a source of income and status, while in Borneo, piracy and slave raiding—sometimes backed by foreign powers—were widespread. The scale of maritime violence was such that the British East India Company was forced to abandon two island settlements off the coast of Borneo in 1775 and 1776.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

END OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, BRITAIN IN INDONESIA AND THE JAVA WAR factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026