LIFE IN MALAYSIA UNDER BRITISH COLONIAL RULE

In 1826, the British combined their settlements in Malacca, Penang, and Singapore to form the Colony of the Straits Settlements. From these strongholds, the British established protectorates over the Malay sultanates on the peninsula during the 19th and early 20th centuries. During their rule, the British developed large-scale rubber and tin production and established a system of public administration. However, British control was interrupted by the Japanese occupation during World War II from 1941 to 1945. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale 2008]

According to UNESCO: The development of Penang and Malacca cities over the centuries was based on the merging of diverse ethnic and cultural traditions, including Malay, European, Muslim, Indian and Chinese influences. All this resulted in a human and cultural tapestry that is expressed in a rich intangible heritage that includes languages, religious practices, gastronomy, ceremonies and festivals.

But the cultures did not merge as seamlessly as has been sometimes purported. Describing an ordinary Malayan town in the 1930s, Mahathir Mohamad wrote, “The rich families lived in the northern part of town; we lived in the southern. And the Europeans of course, lived in there own quarters . They were very exclusive with their own clubs and private golf course and did not mix with the local population.”

In many cases British men arrived without their wives. In some cases Japanese brothels were set up to accommodate them. In the town of Sandakan in northern Borneo, nine such brothels, operated from the early 1900s to World War II. Most of the girls were sex slaves sold by their families and bonded to their brothels where they worked. One Malay man told a Japanese newspaper, “They were very beautiful in their kimonos, and they wore lots of makeup. People like us farmers could not afford Japanese prostitutes. White men got the prettiest ones, followed by the Chinese coolies from the plantations, because they had money and were bachelors.”

The Selangor Club was to Kuala Lumpur what the Pegu Club was to Rangoon and the Tanglin Club to Singapore. At official diners in the 1920s and 30s, waiters wore headdresses and guest were entertained by Filipino bands on the veranda. While on picnic people ate from “tiffin” lunch boxes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS IN MALAYSIA: PORTUGUESE, DUTCH, CONQUESTS, FIGHTING factsanddetails.com

MALACCA SULTANATE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, PARAMESVARA factsanddetails.com

JAMES BROOKE AND MAKING NORTHERN BORNEO PART OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FIGHTING WITH BORNEO PIRATES factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

EARLY KINGDOMS, EMPIRES AND THE ARRIVAL OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Hill Stations

Fraser Hill golf course in 1935

In the intense Asian summers, the English gentry and their servants fled the cities for the hill stations in the cooler mountains. The British built 96 hill stations in India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Burma. The Dutch built some in Indonesia, the French in Vietnam and the Americans in the Philippines. Most were built between 1820 and 1885. Simla, the largest hill station, was the capital of British India for most of the year and headquarters for the imperial army.

The first hill stations were built in 1820 after it was discovered that British soldiers fighting Gurhkas in the foothills of the Himalayas felt better and came down with less diseases in the high altitude than soldiers stationed at low altitudes.

The hill stations began as sanatoriums and convalescent centers, but it wasn’t long before they became places where healthy upper class people went to escape the heat of the lowland plains. Most of the hill stations were located above 6,000 feet because that seemed to be the ceiling of malaria-carrying mosquitos. Naturally cool air proved to be the perfect remedy for a world where air conditioning, insect repellant and antibiotics had not been invented.

Most hill stations were built on ridge tops. Now, while this had its advantages in fighting disease. It was not practical for supplying water, especially when trees were cut down and ground water levels drops. In the early days there were no scenic train rides. Visitors were brought up the slopes in bullock carts, on horseback, or in sedan chairs. A few walked.

Book: Great Hill Stations of Asia by Barbara Crossette (Harper Collins/ Westview, 1998)

Hill Station Life

The hill station were complete towns with sanitariums, churches, cottages, clubs, libraries and activities. Social activities went on almost around the clock and status and rank was rigidly defined. The hill stations were set up like towns back home. They featured comfortable cottages, steepled churches, clubs, schools, tearooms, and gardens with European flowers.

The atmosphere at the hill stations was both formal, strange and hedonistic. People attended full dress balls, drank a lot, slept in closed rooms to avoid the "miasma," indulged in extramarital affairs and had sex with prostitutes. One chronicler wrote, "I verily believe that when the white man penetrates the interior to found a colony, his first act is to clear a space and build a clubhouse."

One journalist described hill station life as "ball after ball, each followed by a little backbiting." Another said, "There is a theory that anyone who lives above 7,000 feet starts having delusions, illusions and hallucinations. People who, in the cities, are the models of respectability are known to fling more than stones and insults at each other when they come to live up here. “

Hill station residents lived quite well. Dinners often features a large selection of wines, ales and spirits, a choice of soups, fish, joints of Bengal mutton, Chinese capons, Keddah fowls, Sangora ducks, Yorkshire hams, Java potatoes and Malay ibis, rice, curry and fruit. Some Indians were invited. Describing the bejeweled maharajahs in Simla, Aldous Huxley wrote," At the Viceroy's evening parties the diamonds were so large they looked like stage gems. It was impossible to believe that pearls in the million-pound necklaces were the genuine excrement of oysters."

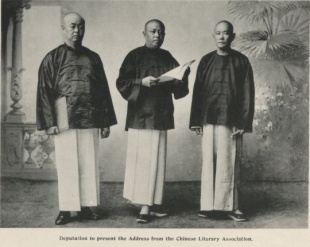

Arrival of Chinese in Malaysia

The first Chinese to enter Southeast Asia were Buddhist monks, maritime traders and representatives of the Imperial Chinese government.. In ancient and medieval times, Chinese traders utilized Southeast Asian ports on maritime Silk Road but in the early days much of this trade was carried out by Arab mariners and merchants. Regular trading between China and Southeast Asia didn’t really begin in earnest until the 13th century. Chinese were attracted by trade opportunities in Malacca, Manila, Batavia (Jakarta). Some of the most detailed descriptions of Angkor Wat and other Southeast Asian civilizations came from Chinese travelers and monks. The Chinese eunuch explorer Zheng He (1371-1433) helped establish Chinese communities in parts of Java and the Malay Peninsula in part, many historians believe, to impose imperial Chinese control.

Beginning in the late-1700s, large numbers of Chinese — mostly from Guangdong and Fujian provinces and Hainan Island in southern China — began emigrating to Southeast Asia. Most were illiterate, landless peasants oppressed in their homelands and looking for opportunities abroad. The rich landowners and educated Mandarins stayed in China. Scholars attribute the mass exodus to population explosion in the coastal cities of Fujian and prosperity and contacts generated by foreign trade.

So many people left Fujian for Southeast Asia during the late 18th century and early 19th century that the Manchu court issued an imperial edict in 1718 recalling all Chinese to the mainland. A 1728 proclamation declared that anyone who didn't return and was captured would be executed.

Most of the Chinese who settled in Southeast Asia left China in the mid 19th century after a number treaty ports were opened in China with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 after the first Opium War. The ports made it easy to leave and with the British rather than imperial Chinese running things there were fewer obstacles preventing them from leaving. British ports in Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore, gave them destinations they could head to.

A particularly large number of Chinese left from the British treaty ports of Xiamen (Amoy) and Fuzhou (Foochow) in Fujian province. Many were encouraged to leave by colonial governments so they could provide cheap coolie labor in ports around the world, including those in colonial Southeast Asia. Many Chinese fled the coastal province of Fujian and Zhejiang after famines and floods in 1910 and later during World War II and the early days of Communist rule. Many of the legal and illegal immigrants from China continue to come from Fujian.

Life and Impact of Chinese in Malaysia

Peranakan Chinese-Malay culture flourished in southwest Malaysia from the 17th century to its peak at the turn of the 20th. The Peranakan culture, also known as Baba-Nyonya — men were called babas, women were nyonyas — incorporated Dutch, English, Portuguese and Indian influences.

Many Chinese immigrants arrived in Malaya with little more than the shirts on their backs, but their emphasis on hard work, thrift, education, and Confucian family values helped them prosper. Strong mutual-aid networks, organized through hui-guan associations, also supported their success. By the 1890s, prominent leaders such as Yap Ah Loy, the Kapitan China of Kuala Lumpur, had become extremely wealthy, controlling mines, plantations, and businesses. From the outset, Chinese entrepreneurs dominated banking, insurance, and commerce, often in partnership with British firms. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Over time, the migrants from China transformed the regional economy, supplying both merchants and wage labor for expanding export industries, particularly tin and gold mining. While indigenous populations also participated in commercial production, especially rice and tin, they largely remained within subsistence-based economies and were reluctant to engage in permanent wage labor. As a result, premodern production remained limited in scale and technologically underdeveloped, and although capitalism had emerged, it was still in its early stages and largely foreign dominated. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia]

As Malay sultans frequently lived beyond their means, many became indebted to Chinese financiers, giving the Chinese community both economic and political influence. Early Chinese migrants were mostly men who initially planned to return to China. While some did, many settled permanently, first marrying Malay women and forming the Sino-Malayan or Baba community, and later bringing Chinese brides to establish lasting communities with their own schools and temples.

The Depression of the 1930s, followed by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, had the effect of ending Chinese emigration to Malaya. This stabilised the demographic situation and ended the prospect of the Malays becoming a minority in their own country. +

Indians in Malaysia

Indians were purposely brought in as a labor force. Unlike some colonial powers, the British always saw their empire as primarily an economic concern, and its colonies were expected to turn a profit for British shareholders. Malaya’s obvious attractions were its tin and gold mines, but British planters soon began to experiment with tropical plantation crops – tapioca, gambier, pepper and coffee. But in 1877 the rubber plant was introduced from Brazil, and rubber soon became Malaya’s staple export, stimulated by booming demand from European industry. Rubber was later joined by palm oil as an export earner.

All these industries required a large and disciplined labour force, and the British did not regard the Malays as reliable workers. The solution was the importation of plantation workers from India, mainly Tamil-speakers from South India. The mines, mills and docks also attracted a flood of immigrant workers from southern China. Soon towns like Singapore, Penang and Ipoh were majority Chinese, as was Kuala Lumpur, founded as a tin-mining centre in 1857. By 1891, when Malaya’s first census was taken, Perak and Selangor, the main tin-mining states, had Chinese majorities. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Indians were initially less successful than the Chinese. Unlike the Chinese they came mainly as indentured labourers to work in the rubber plantations, and had few of the economic opportunities that the Chinese had. They were also a less united community, since they were divided between Hindus and Muslims and along lines of language and caste. An Indian commercial and professional class emerged during the early 20th century, but the majority of Indians remained poor and uneducated in rural ghettos in the rubber-growing areas. +

Attitude of the Malays Towards the Chinese and Indians in Malaysia

Traditional Malay society struggled with the losses of political sovereignty to the British and economic dominance to the Chinese. By the early twentieth century, there was a growing fear that Malays might become a minority in their own land. The sultans—widely viewed as collaborators with both British authorities and Chinese commercial interests—suffered a decline in prestige, particularly among the rising number of Western-educated Malays. Nonetheless, the rural Malay population continued to revere them, and this enduring loyalty made the sultans an important pillar of colonial governance. [Source: Wikipedia +]

At the same time, a small but influential group of Malay nationalist intellectuals began to emerge. This development coincided with a revival of Islam, driven in part by anxiety over the spread of imported religions, especially Christianity. In practice, relatively few Malays converted to Christianity, though conversions among the Chinese were more common. The northern regions of Malaya, less exposed to Western ideas, became centers of Islamic conservatism—a characteristic they have retained.

One source of reassurance for Malay pride was British policy that granted Malays a near monopoly over positions in the police and local military units, as well as a majority of administrative posts open to non-Europeans. While the Chinese largely financed and managed their own schools and colleges—often importing teachers from China—the colonial government actively promoted Malay education. The establishment of the Malay College in 1905 and the creation of the Malay Administrative Service in 1910 reflected this commitment. The college was famously known as Bab ud-Darajat (“Gateway to High Rank”). Further institutions followed, including a Malay Teachers’ College in 1922 and a Malay Women’s Training College in 1935. These initiatives embodied the British belief that Malaya fundamentally belonged to the Malays, with other ethnic groups regarded as temporary residents. Increasingly detached from demographic and social realities, this assumption sowed the seeds of future conflict.

The Malay Teachers’ College in particular became a center for nationalist thought, with lectures and writings that fostered anti-colonial sentiment. As a result, it is often described as the birthplace of Malay nationalism. In 1938, Ibrahim Yaacob, an alumnus of Sultan Idris College, founded the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM, or Young Malays Union) in Kuala Lumpur. The first nationalist political organization in British Malaya, the KMM advocated unity among all Malays regardless of origin, championed Malay rights, and opposed British imperial rule. One of its defining ideals was Panji Melayu Raya, which called for the unification of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies.

In the years preceding World War II, British policymakers grappled with balancing administrative centralization against preserving the authority of the sultans. No steps were taken toward creating a unitary government; instead, decentralization prevailed. In 1935, the post of Resident-General of the Federated Malay States was abolished, and its powers devolved to the individual states. British attitudes were shaped by racial stereotypes: Malays were seen as good-natured but unsophisticated and allegedly incapable of self-rule, though suitable as soldiers under British command. The Chinese were regarded as intelligent but potentially dangerous. Indeed, during the 1920s and 1930s, influenced by political developments in China, both the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) and the Communist Party of China established rival underground networks in Malaya, leading to periodic unrest in Chinese urban centers. To British officials, Malaya’s fragmented collection of states and ethnic communities seemed incapable of forming a nation—much less achieving independence.

Migrants and the Malaysian Economy Before World War II

By the 1920s, large-scale migration had created a highly multi-ethnic population in Malaya. British scholar J. S. Furnivall later described this kind of society as a “plural society,” in which different ethnic groups lived side by side under one government but had little social or cultural interaction beyond economic activity. Many migrants originally planned to stay only a few years, earn money, and return home. Over time, however, increasing numbers settled permanently, raised families, and made Malaya their home. [Source: John H. Drabble, University of Sydney, Australia +]

Economic development was uneven across the country. Most tin mines and rubber estates were located along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. During economic booms, immigrant populations in these areas often outnumbered the indigenous Malays. Chinese and Indian communities recreated the social institutions, languages, and hierarchies of their home countries, especially the Chinese. They dominated major commercial centers such as Penang, Singapore, and Kuching, and controlled much of the local trade in smaller towns and villages through networks of shops and dealerships. These networks linked rural producers to global markets by exporting goods such as rubber and importing manufactured products. Chinese entrepreneurs also owned substantial mining and agricultural land.

As a result, wealth and economic roles became closely linked to race. This created growing resentment among the bumiputera, who feared they were losing their ancestral land and becoming economically marginalized. Under British rule, ethnic groups generally relied on the colonial government to protect their interests and maintain stability. One example of this paternalistic approach was the introduction in 1913 of Malay Reservations, which restricted land ownership in certain areas to indigenous Malays.

Early Twentieth Century Malaysia

By the late nineteenth century, stable forms of government had emerged in Malaysia, and its economy and culture began to assume characteristics that would endure for decades. In the late 1800s, copious deposits of tin ore were discovered in the northwestern state of Perak, and this led to substantial growth in mining and the creation of administrative and transportation infrastructure to service the tin industry, which in turn enabled the growth of other industries along the west coast, such as rubber plantations. This early export diversification helped the economy respond to changing international prices for primary commodities and generally aided economic growth. [Source: Wikipedia +]

In addition, an ethnic Malay identity began to emerge in this period. Although ethnic Malays shared a common religion in Islam and a common language in Malay, their social identities were often localized to their respective states, and their political loyalties were generally to their respective sultans. By contrast, the Chinese and Indians in Malaysia often occupied particular economic niches, which helped instill in them more distinct and salient ethnic identities. This situation began to change in the early 1900s with the emergence of Malay cultural organizations and publications. These entities had numerous political differences but generally claimed that Malays share a common ethnicity and thus promoted the emergence of the Malay nation. +

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026