COMMODORE PERRY AND THE AMERICANS ARRIVES IN JAPAN

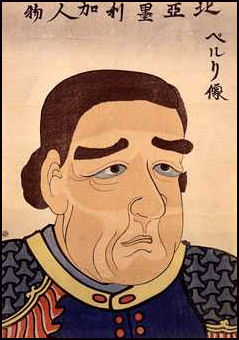

Japanese depiction of

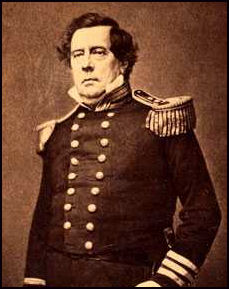

Perry's Black Ship In 1852, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) of the United States Navy was dispatched to Japan by U.S. President Millard Fillmore (1800-1874). On July 8, 1853, Perry, commanding a squadron of two steamers and two sailing vessels, arrived in Uraga harbor, near the Tokugawa capital of Edo (Tokyo) aboard the frigate Susquehanna and forced Japan to enter into trade with the United States. Upon seeing Perry's fleet sailing into their harbor, the Japanese called them the "black ships of evil mien (appearance)." Many leaders wanted the foreigners expelled from the country.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “As expressed in a letter from President Fillmore to the Japanese Emperor, delivered by Perry to the worried Tokugawa officials who greeted him, the United States was eager to break Japan’s “seclusion policy,” sign diplomatic and commercial treaties, and thus “open” the nation to the Western world. For the Japanese, who had carefully regulated overseas contacts since the seventeenth century and whose technology could not compare to that displayed by the American squadron, Perry’s arrival and President Fillmore’s letter were unwelcome and ominous, even if not entirely unexpected. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Perry stayed in Uraga for fewer than ten days in 1853, withdrawing to the China coast with his ships. As he promised in his letter of July 14, 1853, however, he returned to Japan about six months later with a much larger and more intimidating fleet, comprising six ships with more than 100 mounted cannon. In March of 1854, the Tokugawa shogunate capitulated to all the American demands, signing the Treaty of Kanagawa with Perry. “

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; MEIJI RESTORATION: REBELLIONS, YOSHIDA SHION, SAKAMOTO RYOMA AND THE MEIJI EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) EMPEROR, LEADERS AND STATE SHINTO factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) REFORMS, MODERNIZATION AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; MEIJI CONSTITUTION factsanddetails.com; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Perry Visits Japan, a Visual History brown.edu/japan/images ; Black Ships and Samurai MIT Visualizing Culture ; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ; Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “With Commodore Perry to Japan: The Journal of William Speiden, Jr., 1852-1855" by John A. Wolter, David A. Ranzan Amazon.com; “The First European Description of Japan, 1585" by Luis Frois Amazon.com; “Black Ships Off Japan - The Story of Commodore Perry's Expedition” by Arthur Walworth Amazon.com; “Breaking Open Japan: Commodore Perry, Lord Abe, and American Imperialism in 1853" by George Feifer Amazon.com; “Japan before Perry: A Short History” by Conrad Totman Amazon.com; “The Perry Expedition and the "Opening of Japan to the West," 1853–1873: A Short History with Documents” by Paul Hendrix Clark Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan” by John Whitney Hall (Editor), James L. McClain Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912" Illustrated (2005) by Donald Keene Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “Meiji Restoration Losers: Memory and Tokugawa Supporters in Modern Japan (Harvard East Asian Monographs)” by Michael Wert Amazon.com

Tokugawa Japan at the Time of Perry’s Arrival

Tokugawa Yoshinobu

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ Japan at this time was ruled by the shôgun ("great general") from the Tokugawa family. The Tokugawa shogunate was founded about 250 years earlier, in 1603, when Tokugawa leyasu (his surname is Tokugawa) and his allies defeated an opposing coalition of feudal lords to establish dominance over the many contending warlords. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“But while Tokugawa became dominant, receiving the title of shôgun from the politically powerless emperor, he did not establish a completely centralized state. Instead, he replaced opposing feudal lords with relatives and allies, who were free to rule within their domains under few restrictions. The Tokugawa shôguns prevented alliances against them by forbidding marriages among the other feudal lords' family members and by forcing them to spend every other year under the shôgun's eye in Edo (now Tôkyô), the shogunal capital — in a kind of organized hostage system.

“It was the third shôgun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, who enforced isolation from much of the rest of the world in the seventeenth century, believing that influences from abroad (meaning trade, Christianity, and guns) could shift the balance that existed between the shôgun and the feudal lords. He was proven right two centuries later, when change came in the form of Perry's ships.”

Japanese Interest in the West

Hasekura in Rome

In 1612, a violent storm washed a British ship ashore in the Miyagi coast. Using the ship as a model, a local lord constructed Japan’s first open sea vessel and on it sent an envoy, Tsunenaga Hasekura, to Mexico to forge trade links with the Spanish. Hasekura landed in Acapulco, made his way across Mexico and traveled to Europe where he was received by Pope Paul V in Rome.Hasekura was baptized a Catholic and returned to Japan in 1620. He expected a hero’s welcome but instead was ignored. No one seemed particularly interested in what he learned about the outside world and he spent his last years living in seclusion.

The "opening" of China in the early 19th century generated interest in Japan in the West. Western merchants were particularly interested in making profits from trade with Japan and using Japanese ports. An article from the Edinburgh Review in 1852 stated: "The compulsory seclusion of the Japanese is wrong, not only to themselves but to the civilized world."

France and Japan had their first significant encounter in 1844 in the Ryukyu Islands and from 1855 through Hakadote and Nagasaki. Many of their early engagements revolved around the silk trade. Lyon, France was a major center of silk and textile production and Japan produced the best quality silks, better than those produced in China. For a while the purchase of silkworm eggs and raw silk from Japan by France accounted for more than half the world’s silk production.

Hermann Melville wrote in “Moby Dick” (1851), "If that double-bolted land, Japan, is ever to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone to whom the credit will be due, for already she is on the threshold.”

Admiral Perry in Japan

U.S. President Millard Fillmore sent American Commodore Matthew Perry (1794-1858) and a forth of the U.S. Navy---three steam frigates and five other warships---to establish diplomatic and trade relations with Japan. The main purpose of Perry's mission was to establish a coal station in Japan so that steam ships could journey from the United States to China and Asia along the "great circle route" via Alaska. The United States government wanted to make sure they got to Japan first so it wouldn't fall into the hands of a European rival and disrupt American plans to control trade in the Pacific. [Source: James Fallows, Smithsonian magazine]

Perry arrived in Edo (present-day Tokyo) Bay in July, 1853 with two steamers and two sailing vessels and was greeted sword-wielding samurai in wooden rowboats. Perry’s steamships had steel-reinforced hulls and an array of weapons. His flagship was the largest and most modern steamship in the world at that time. They are know in Japan today as the "black ships.” To reach Japan, Perry 7½ months at seas and sailed across the Atlantic, around Africa and stopped in Sri Lanka, Singapore and Shanghai.

Perry was 59 when he arrived in Tokyo Bay. He suffered from arthritis and a number of other maladies and was confined to his quartered for much of the voyage. Often compared with Douglas MacArthur, he was a proud and short-tempered man, who saw very little action is his naval career (during the early years of the American navy more officers were killed in duels than fighting and Perry himself did not see any combat action until he was in his 50s). Before arriving in Japan he pursued pirates in the Caribbean, fought in the Mexican War. His first important mission was to take freed slaves to the new country of Liberia in 1819.

According to the Library of Congress: Japan had "turned down a demand from the United States, which was greatly expanding its own presence in the Asia-Pacific region, to establish diplomatic relations when Commodore James Biddle appeared in Edo Bay with two warships in July 1846. However, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry's four-ship squadron appeared in Edo Bay in July 1853, the Shogunate was thrown into turmoil. The chairman of the senior councillors, Abe Masahiro (1819-57), was responsible for dealing with the Americans. Having no precedent to manage this threat to national security, Abe tried to balance the desires of the senior councillors to compromise with the foreigners, of the emperor who wanted to keep the foreigners out, and of the daimyo who wanted to go to war. Lacking consensus, Abe decided to compromise by accepting Perry's demands for opening Japan to foreign trade while also making military preparations. In March 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity (or Treaty of Kanagawa) opened two ports to American ships seeking provisions, guaranteed good treatment to shipwrecked American sailors, and allowed a United States consul to take up residence in Shimoda, a seaport on the Izu Peninsula, southwest of Edo. A commercial treaty, opening still more areas to American trade, was forced on the Shogunate five years later. [Source: Library of Congress]

Face-Off Between Perry and the Japanese

Japanese depiction

of Perry None of the Japanese that encounter the American ships understood English and no one on Perry's ship could speak Japanese. The first word spoken by either party was French, which neither group understood very well either. A leader on Japanese boats shouted, "Départez!," "Depart Immediately!" [Source: James Fallows, Smithsonian magazine]

Perry's ships didn't leave. They blocked the shipping lanes of Edo (Tokyo) and despite the language barrier Perry made it clear he wouldn't move until a treaty was signed. He refused to talk to local officials and demanded to see the governor. Perry’s Black Ships were like nothing ever seen in Japan before. The USS Susquehanna, the 78-meter flagship, dwarfed the 24-meter sengokubane, the largest Japanese craft at that time.

For a while Perry and the Japanese played a cat and mouse game. The American sent surveying ships further and further into Tokyo Bay and on several occasions violencealmost erupted. In the meantime, Japanese citizens fearing a major attack by the Americans, headed into the countryside for safety.

Perry had orders to deliver a letter from U.S. President Fillmore requesting that Japan open itself to the world trade, provide protection shipwrecked seamen, allow ships to purchase coal and water and other demands.

In the end Perry was allowed to come ashore but he was not allowed to go to Edo or Kyoto to meet the emperor or shogun. Although some Japanese suggested an attack on the fleet, the militarily-weak shogun felt he no choice but to sign a treaty.

The Japanese had observed how mighty China Kingdom, whose emperor referred to the Japanese emperor as the "little king," had been carved up by the European powers. They didn't want the same thing to happen to them, plus they knew that if they attacked the American ships, the chances were a larger flotilla might return to exact retribution. The idea was for Japan to open up to the West for only a short time---just long enough to learn their technology and rebuild their army and navy---and then get rid of them.

Perry Sets Foot in Japan

One the morning he was scheduled to come ashore to meet a representative of the shogun, Perry feared an ambush and ordered his gunboats to come close enough to the shore where the could fire on the Japanese if anything went wrong. The Japanese in turn had ten sword-wielding samurai hiding under a trap door. If anything went wrong they were ordered to leap out and slay the foreigners.[Source: James Fallows, Smithsonian magazine]

At 10 o'clock in the morning in July 14, 1853, Perry walked ashore at Yokosuka (south of present-day Yokohama and Tokyo) between a double line of heavily armed soldiers. In front of him was a marine with a sword and at his side were two of the largest men from his ship, two black stewards, carrying all kinds of weapons and towering over everybody.

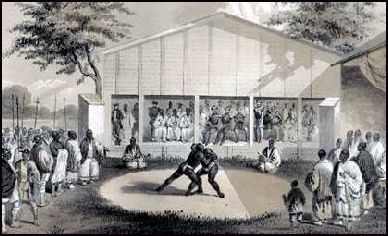

Once Perry was on shore, the tension eased a bit. Perry gave the Japanese representative a plow, a scythe, a grindstone, a quarter-size steam locomotive, the letter from President Fillmore, some whiskey and a white flag accompanied by instructions on how to use it to surrender. The Japanese treated the Americans to a demonstration of sumo wresting. Perry wrote that he poked the stomach of one of the wrestlers, who emitted "a self-satisfied grunt.”

Perry introduced the Japanese to milk and soap and had a cow slaughtered to promote the virtues of American beef. The Japanese introduced the Americans to seaweed, unique seafood dishes and men and women bathing nude together in public baths---a show of immodesty that drew of critical response from Perry.

Some Japanese boarded the ships. One Japanese man who saw the sailors lounging in hammocks thought they were being suspended from the ceiling as a form of punishment. A samurai who came aboard saw his images in a mirror for the first time and thought he was encountering a Western samurai. Some Japanese who got their hands on Western soap and thought it was food. They were surprised as it disappeared into bubbles when they cooked it. The artists who drew the American began the pictures with a large nose.

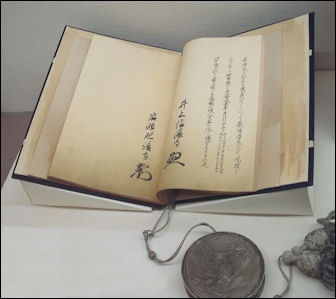

Letter from U.S. President Millard Fillmore to the Emperor of Japan

The following letter from the United States to Japan asked that Japan open its doors to trade. Although the letter was addressed to the emperor, it was the shôgun, the ruler of Japan, who received it. [Source: “Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to China and Japan, performed in the years 1852,1853, and 1854, under the Command of Commodore M. C. Perry United States Navy, by Order of the Government of the United States,” compiled by Francis L. Hawks, vol. I (Washington, D.C., A.O.P. Nicholson, Printer, 1856), 256-259 ]

From Millard Fillmore, President of the United States of America, to His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Japan, November 13, 1852: “GREAT and Good Friend: I send you this public letter by Commodore Matthew C. Perry, an officer of the highest rank in the navy of the United States, and commander of the squadron now visiting your imperial majesty’s dominions. I have directed Commodore Perry to assure your imperial majesty that I entertain the kindest feelings towards your majesty’s person and government, and that I have no other object in sending him to Japan but to propose to your imperial majesty that the United States and Japan should live in friendship and have commercial intercourse with each other. The Constitution and laws of the United States forbid all interference with the religious or political concerns of other nations. I have particularly charged Commodore Perry to abstain from every act which could possibly disturb the tranquility of your imperial majesty’s dominions.

The United States of America reach from ocean to ocean, and our Territory of Oregon and State of California lie directly opposite to the dominions of your imperial majesty. Our steamships can go from California to Japan in eighteen days. Our great State of California produces about sixty millions of dollars in gold every year, besides silver, quicksilver, precious stones, and many other valuable articles. Japan is also a rich and fertile country, and produces many very valuable articles. Your imperial majesty’s subjects are skilled in many of the arts. I am desirous that our two countries should trade with each other, for the benefit both of Japan and the United States.

We know that the ancient laws of your imperial majesty’s government do not allow of foreign trade, except with the Chinese and the Dutch; but as the state of the world changes and new governments are formed, it seems to be wise, from time to time, to make new laws. There was a time when the ancient laws of your imperial majesty’s government were first made. About the same time America, which is sometimes called the New World, was first discovered and settled by the Europeans. For a long time there were but a few people, and they were poor. They have now become quite numerous; their commerce is very extensive; and they think that if your imperial majesty were so far to change the ancient laws as to allow a free trade between the two countries it would be extremely beneficial to both.

Image possibly showing Perry reading letter by President Fillmore

If your imperial majesty is not satisfied that it would be safe altogether to abrogate the ancient laws which forbid foreign trade, they might be suspended for five or ten years, so as to try the experiment. If it does not prove as beneficial as was hoped, the ancient laws can be restored. The United States often limit their treaties with foreign states to a few years, and then renew them or not, as they please.

I have directed Commodore Perry to mention another thing to your imperial majesty. Many of our ships pass every year from California to China; and great numbers of our people pursue the whale fishery near the shores of Japan. It sometimes happens, in stormy weather, that one of our ships is wrecked on your imperial majesty’s shores. In all such cases we ask, and expect, that our unfortunate people should be treated with kindness, and that their property should be protected, till we can send a vessel and bring them away. We are very much in earnest in this.

Commodore Perry is also directed by me to represent to your imperial majesty that we understand there is a great abundance of coal and provisions in the Empire of Japan. Our steamships, in crossing the great ocean, burn a great deal of coal, and it is not convenient to bring it all the way from America. We wish that our steamships and other vessels should be allowed to stop in Japan and supply themselves with coal, provisions, and water. They will pay for them in money, or anything else your imperial majesty’s subjects may prefer; and we request your imperial majesty to appoint a convenient port, in the southern part of the empire, where our vessels may stop for this purpose. We are very desirous of this.

These are the only objects for which I have sent Commodore Perry, with a powerful squadron, to pay a visit to your imperial majesty’s renowned city of Edo: friendship, commerce, a supply of coal and provisions, and protection for our shipwrecked people. We have directed Commodore Perry to beg your imperial majesty’s acceptance of a few presents. They are of no great value in themselves; but some of them may serve as specimens of the articles manufactured in the United States, and they are intended as tokens of our sincere and respectful friendship.

May the Almighty have your imperial majesty in His great and holy keeping! In witness whereof, I have caused the great seal of the United States to be hereunto affixed, and have subscribed the same with my name, at the city of Washington, in America, the seat of my government, on the thirteenth day of the month of November, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty.two.

Your good friend,

Millard Fillmore

By the President:

Edward Everett, Secretary of State

Letters from Commodore Perry to the Emperor of Japan

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the US, 1858

The following letter from the United States to Japan asked that Japan open its doors to trade. Although the letter was addressed to the emperor, it was the shôgun, the ruler of Japan, who received it. [Source: “Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to China and Japan, performed in the years 1852,1853, and 1854, under the Command of Commodore M. C. Perry United States Navy, by Order of the Government of the United States,” compiled by Francis L. Hawks, vol. I (Washington, D.C., A.O.P. Nicholson, Printer, 1856), 256-259 ]

From Commodore Matthew C. Perry, United States Steam Frigate Susquehanna, Off the Coast of Japan, To His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Japan, July 7, 1853: “THE undersigned, commander.in.chief of all the naval forces of the United States of America stationed in the East India, China and Japan seas, has been sent by his government of this country, on a friendly mission, with ample powers to negotiate with the government of Japan, touching certain matters which have been fully set forth in the letter of the President of the United States, copies of which, together with copies of the letter of credence of the undersigned, in the English, Dutch, and Chinese languages, are herewith transmitted.

The original of the President’s letter, and of the letter of credence, prepared in a manner suited to the exalted station of your imperial majesty, will be presented by the undersigned in person, when it may please your majesty to appoint a day for his reception. The undersigned has been commanded to state that the President entertains the most friendly feelings towards Japan, but has been surprised and grieved to learn that when any of the people of the United States go, of their own accord, or are thrown by the perils of the sea, within the dominations of your imperial majesty, they are treated as if they were your worst enemies. The undersigned refers to the cases of the American ships Morrison, Lagoda, and Lawrence.

With the Americans, as indeed with all Christian people, it is considered a sacred duty to receive with kindness, and to succour and protect all, of whatever nation, who may be cast upon their shores, and such has been the course of the Americans with respect to all Japanese subjects who have fallen under their protection. The government of the United States desires to obtain from that of Japan some positive assurance that persons who may hereafter be shipwrecked on the coast of Japan, or driven by stress of weather into her ports, shall be treated with humanity.

tobacco collected by Perry

The undersigned is commanded to explain to the Japanese that the United States are connected with no government in Europe, and that their laws do not interfere with the religion of their own citizens, much less with that of other nations. That they inhabit a great country which lies directly between Japan and Europe, and which was discovered by the nations of Europe about the same time that Japan herself was first visited by Europeans; that the portion of the American continent lying nearest to Europe was first settled by emigrants from that part of the world; that its population has rapidly spread through the country, until it has reached the shores of the Pacific Ocean; that we have now large cities, from which, with the aid of steam vessels, we can reach Japan in eighteen or twenty days; that our commerce with all this region of the globe is rapidly increasing, and the Japan seas will soon be covered with our vessels.

Therefore, as the United States and Japan are becoming every day nearer and nearer to each other, the President desires to live in peace and friendship with your imperial majesty, but no friendship can long exist, unless Japan ceases to act towards Americans as if they were her enemies. However wise this policy may originally have been, it is unwise and impracticable now that the intercourse between the two countries is so much more easy and rapid than it formerly was. The undersigned holds out all these arguments in the hope that the Japanese government will see the necessity of averting unfriendly collision between the two nations, by responding favourably to the propositions of amity, which are now made in all sincerity.

Many of the large ships.of.war destined to visit Japan have not yet arrived in these seas, though they are hourly expected; and the undersigned, as an evidence of his friendly intentions, has brought but four of the smaller ones, designing, should it become necessary, to return to Edo in the ensuing spring with a much larger force. But it is expected that the government of your imperial majesty will render such return unnecessary, by acceding at once to the very reasonable and pacific overtures contained in the President’s letter, and which will be further explained by the undersigned on the first fitting occasion. With the most profound respect for your imperial majesty, and entertaining a sincere hope that you may long live to enjoy health and happiness, the undersigned subscribes himself,

M. C. Perry,

Commander-in-chef of the United States Naval Forces in the East India, China, and Japan seas

A week later, Perry sent a second letter: From Commodore Matthew C. Perry [Sent in Connection with the Delivery of a White Flag], July 14, 1853: For years several countries have applied for trade, but you have opposed them on account of a national law. You have thus acted against divine principles and your sin cannot be greater than it is. What we say thus does not necessarily mean, as has already been communicated by the Dutch boat, that we expect mutual trade by all means. If you are still to disagree we would then take up arms and inquire into the sin against the divine principles, and you would also make sure of your law and fight in defence. When one considers such an occasion, however, one will realize the victory will naturally be ours and you shall by no means overcome us. If in such a situation you seek for a reconciliation, you should put up the white flag that we have recently presented to you, and we would accordingly stop firing and conclude peace with you, turning our battleships aside. [Source: “Meiji Japan through Contemporary Sources,” Volume Two: 1844-1882, compiled and published by the Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, c/o The Toyo Bunko, Honkomagome 2-chome 28-21, Bunkyo-ku; Tokyo, 113 Japan ]

Commodore Perry

Perry's Return to Japan

sumo exhibition for Perry The Japan gave Perry a letter that told the Americans they had broken Japanese law and warned them never to come back. Perry then told the Japanese he would leave soon but return the following year. After traveling all that time to get to Japan, Perry only spent four days there. At the time of Perry's visit, the Japanese government was almost bankrupt, it lacked a navy and it coastal defenses were unable to withstand an assault by the black ships. While Perry was away, the Japanese repealed their laws that prohibited the construction of sea-going vessels and opened negotiations with the Dutch to buy some steamships. [Source: James Fallows, Smithsonian magazine]

After several months in China, Perry returned to Japan on March 13, 1854, with a much larger force (ten ships with 100 mounted cannon and 1,500 men) to intimidate the shogunate with a show of potential force.. He also brought large supplies of champagne, good wine and fresh livestock for meat to entertain his Japanese hosts with an elaborate banquet. After being sufficiently wined and dined aboard Perry’s ship, the Powhatan, the Tokugawa shogunate capitulated to all the American demands, signing the Treaty of Kanagawa --- the Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States and Japan --- with Perry on March 31, 1854.

The commercial treaty between Japan and the United States was worked out by Townsend Harris, a New York businessman who lived and worked almost entirely alone in Japan. One of the major goals of the expedition was to secure an agreement allowing U.S. whaling ships to call on Japanese ports and take on supplies. According to the agreement made with Japan, the whale ships could only take on supplies as “gifts” with any payment offered seen as a reciprocal “gift.” Harris’s stay in Japan was plagued by troubles. The parent’s of a woman servant assigned to him demand compensation because her association with foreigners made her tainted and unmarriagable. His Dutch assistant was murdered on the street by disgruntled samurai unhappy about the presence of foreigners in Japan.

Describing this visit Perry wrote, "During our stay in Edo Bay, all the officers and members of the crews had frequent opportunities of mingling freely with the people, both ashore and on board, as many of the natives visited the ships."

Perry’s strategy had worked. The Japanese government, with some reluctance, signed more diplomatic treaties with the United States. In 1854 a treaty was signed between the United States and Japan which allowed trade at two ports. In 1858 another treaty was signed which opened more ports and designated cities in which foreigners could reside.

Perry correctly predicted that even though Japan was behind the West in many respects at that time it would catch up fast and become a theological leader, “[Japan’s] craftsmen are as expert as any in the world, and with freer development of the inventive powers of the people, the Japanese would not remain long behind he most successful manufacturing nations...the Japanese would enter as powerful competitors in the race for mechanical success in the future.”

Japan Opens to the West

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the US, 1858

The treaty resulting from Perry’s visit---the Kanagawa Treaty---allowed whalers safe passage from Japanese shores, gave the Americans permission to take coal from Japan, established diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States, stipulated low import duties and opened up two Japanese ports to foreign trade. Perry still wasn't allowed to visit Edo but he was given permission to view it from the deck of his ship.

Perry's visit forced Japan to end its isolation. New treaties were signed with Russia, Britain and the Netherlands, and social and political changes took place that undermined the foundations of the feudal structure, created great turmoil and unrest that eventually led to the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate.The visit also resulted in anti government feelings. Japanese felt the Tokugawa shogunate had failed to halt an invasion by foreigners and allowed Japan to stagnate to such a degree that it was vulnerable to foreign domination.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Perry, on behalf of the U.S. government, forced Japan to enter into trade with the United States and demanded a treaty permitting trade and the opening of Japanese ports to U.S. merchant ships. This was the era when all Western powers were seeking to open new markets for their manufactured goods abroad, as well as new countries to supply raw materials for industry. It was clear that Commodore Perry could impose his demands by force. The Japanese had no navy with which to defend themselves, and thus they had to agree to the demands. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Perry's small squadron itself was not enough to force the massive changes that then took place in Japan, but the Japanese knew that his ships were just the beginning of Western interest in their islands. Russia, Britain, France, and Holland all followed Perry's example and used their fleets to force Japan to sign treaties that promised regular relations and trade. They did not just threaten Japan — they combination their navies on several occasions to defeat and disarm the Japanese feudal domains that defied them.”

Impact of Perry’s Visit

With the opening of the nation, prices of major exports such as raw silk quadrupled at once. As the gold-silver exchange rates in Japan and abroad differed, an exodus of Japanese gold occurred. The reminting of koban---a Japanese gold coin of the Edo period (1603-1867)’spurred hyperinflation. Riding the tide of trade liberalization, newly emerging merchants came to the fore, while long-established wholesalers in Tokyo and Osaka lost their monopoly on the distribution of goods. These developments can be likened to the implementation of trade liberalization, currency devaluation, distribution system reform and regulatory reform all at once. Although the country's economy became chaotic, these major changes did lay the foundations for the rapid modernization of Japan's economy. [Source: James Fallows, Smithsonian magazine]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “ While some Japanese welcomed this expansion of foreign relations, others interpreted it as a sign of bakufu weakness and incompetence. Diverse groups began to unite in their dislike of the bakufu, adopting the slogan "sonno joi," ("Revere the sovereign; expel the barbarians!") The "sovereign" in this case meant the emperor, and the "barbarians" were the American and European foreigners. Those who disliked the bakufu for whatever reason began to rally around this slogan, and dissident samurai began a campaign of terror by assassination. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The trade brought much foreign currency into Japan disrupting the Japanese monetary system. Because the ruling shôgun seemed unable to do anything about the problems brought by the foreign trade, some samurai leaders began to demand a change in leadership. The weakness of the Tokugawa shogunate before the Western demand for trade, and the disruption this trade brought, eventually led to the downfall of the Shogunate and the creation of a new centralized government with the emperor as its symbolic head. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Black Ship scroll

Impact of Perry's Visit on the Tokugawa Shogunate

Perry’s first visit to Japan in 1853 caused social upheaval in the closing days of the Tokugawa shogunate and led to the Meiji Restoration. Debate over government policy was unusual and had engendered public criticism of the Shogunate. In the hope of enlisting the support of new allies, Abe, to the consternation of the fudai, had consulted with the shinpan and tozama daimyo, further undermining the already weakened Shogunate. In the Ansei Reform (1854-56), Abe then tried to strengthen the regime by ordering Dutch warships and armaments from the Netherlands and building new port defenses. In 1855 a naval training school with Dutch instructors was set up at Nagasaki, and a Western-style military school was established at Edo; by the next year, the government was translating Western books. Opposition to Abe increased within fudai circles, which opposed opening Shogunate councils to tozama daimyo, and he was replaced in 1855 as chairman of the senior councillors by Hotta Masayoshi (1810-64). [Source: Library of Congress *]

At the head of the dissident faction was Tokugawa Nariaki, who had long embraced a militant loyalty to the emperor along with antiforeign sentiments, and who had been put in charge of national defense in 1854. The Mito school--based on neo-Confucian and Shinto principles--had as its goal the restoration of the imperial institution, the turning back of the West, and the founding of a world empire under the divine Yamato Dynasty. *

In the final years of the Tokugawa, foreign contacts increased as more concessions were granted. The new treaty with the United States in 1859 allowed more ports to be opened to diplomatic representatives, unsupervised trade at four additional ports, and foreign residences in Osaka and Edo. It also embodied the concept of extraterritoriality (foreigners were subject to the laws of their own countries but not to Japanese law). Hotta lost the support of key daimyo, and when Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta sought imperial sanction. The court officials, perceiving the weakness of the Shogunate, rejected Hotta's request and thus suddenly embroiled Kyoto and the emperor in Japan's internal politics for the first time in many centuries. When the shogun died without an heir, Nariaki appealed to the court for support of his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (or Keiki), for shogun, a candidate favored by the shinpan and tozama daimyo. The fudai won the power struggle, however, installing Tokugawa Yoshitomi, arresting Nariaki and Keiki, executing Yoshida Shoin (1830-59, a leading sonno-joi intellectual who had opposed the American treaty and plotted a revolution against the Shogunate), and signing treaties with the United States and five other nations, thus ending more than 200 years of exclusion. *

The strong measures the Shogunate took to reassert its dominance were not enough. Revering the emperor as a symbol of unity, extremists wrought violence and death against the Shogunate and han authorities and foreigners. Foreign naval retaliation led to still another concessionary commercial treaty in 1865, but Yoshitomi was unable to enforce the Western treaties. A Shogunate army was defeated when it was sent to crush dissent in Satsuma and Choshu han in 1866. Finally, in 1867, the emperor died and was succeeded by his minor son Mutsuhito; Keiki reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and shogun. He tried to reorganize the government under the emperor while preserving the shogun's leadership role. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Choshu daimyo, other daimyo called for returning the shogun's political power to the emperor and a council of daimyo chaired by the former Tokugawa shogun. Keiki accepted the plan in late 1867 and resigned, announcing an "imperial restoration." The Satsuma, Choshu, and other han leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868. The Shogunate was abolished, Keiki was reduced to the ranks of the common daimyo, and the Tokugawa army gave up without a fight (although other Tokugawa forces fought until November 1868, and Shogunate naval forces continued to hold out for another six months). *

Black ship scroll

Western Technology Introduced to Japan

"For the first few days after our arrival at Yokohama, "Perry wrote, "the requisite number of mechanics, was employed in unpacking and putting in working order the locomotive engine" and "were equally busy in preparing to erect the telegraphic posts for the extension of magnetic lines" and "agricultural implements, all intended for presentation to the Emperor, after first being exhibited and explained.”

"A flat piece of ground was assigned to the engineers for laying down the track of the locomotive. Posts were brought and erected as directed...and telegraph wires of nearly a mile in a direct line were soon extended...The beautiful little engine with its tiny car set in motion...exciting the utmost wonder in the minds of the Japanese.

"Although this perfect piece of machinery was...much smaller than I had expected it would have been, the car was incapable of admitting with any comfort even a child of six years. The Japanese therefore who rode upon it were seated upon the roof, whilst the engineer places himself upon the tender."

Some ancient bells taken from Okinawa by Commander Perry now ring the score at Army-Navy football games.

Samurai in Washington and New York

In 1860, six years after Commodore Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay, more than 70 samurai visited the United States. They were the first known group to officially leave Japan in more than 200 years. They were sent to deliver a treaty of amity and commerce to President James Buchanan and ordered to avoid fraternizing with their American hosts. “But good old aggressive American hospitality took over,” Martha Schwendener wrote in the New York Times, “There were parades and parties, and Walt Whitman even wrote a poem, which was printed on Page 2 of The New York Times.” [Source: Martha Schwendener, New York Times, August 26, 2010

In Washington, the samurai mission exchanged documents ratifying the Japan-U.S. Treaty of Amity and Commerce. The mission, all sporting top knots and carrying swords, met with U.S. President James Buchanan in Washington. According to one of the mission members Buchanan had “gentle looks and smiles” as he greeted the mission. “Ever since our arrival at the American capital,” Norimasa Muragaki, an ambassador, wrote in his diary on June 4, 1860, in Washington, “we have frequently been asked by photographers to allow our photographs to be taken, but we have hitherto refused, as it is not the custom in our country. Today, however, we had to submit, in deference to the President’s wishes...We therefore, for the first time, faced the photograph machine.”

During the visit Americans also introduced the Japanese American-style shopping. A week before their departure in June 1860 an article appeared in The New York Times, describing the delegates’ activities. Their baggage already increases to such huge proportions,” it said, “that even the capacious ‘Niagara’ bids fair to be well filled, and still they shop.”

Letter from the Japan Emperor to U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant in 1871

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In 1871, the fledgling Meiji government dispatched a mission of almost fifty high officials and scholars to travel around the world, including extended tours of the United States, Western Europe, Scandinavia, and Russia. The Iwakura Mission (named after its leader, Iwakura Tomomi, 1825-1883) spent almost two years studying the political, economic, social, legal, and educational systems of the developed world as potential models for the modernization of Japan. The leaders of the mission also attempted to begin the renegotiation of the "unequal treaties" — the exploitative diplomatic and economic agreements imposed by the Western powers on Japan in the 1850s, although governments in America and Europe were not yet willing to relax any of their privileges in Japan. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

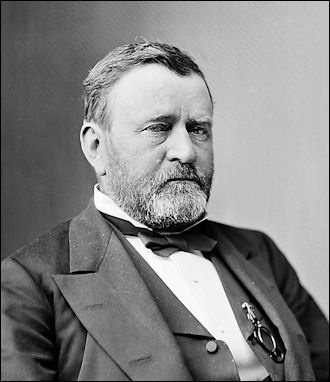

US President US Grant

The following letter from the Emperor Meiji (Mutsuhito, 1852-1912; r. 1867-1912) was presented to U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) when the Iwakura Mission visited Washington, D.C. [Source: “Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period”, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 324; NOTE: This text was adopted from the official translation as reproduced in The New York Times, March 15, 1872.]

Excerpts from the Letter from Emperor Meiji (Mutsuhito) to President Ulysses S. Grant, on the Iwakura Mission, 1871: Mitsuhito, Emperor of Japan, etc., to the President of the United States of America, our good brother and faithful friend, greeting: Mr. President: Whereas since our accession by the blessing of heaven to the sacred throne on which our ancestors reigned from time immemorial, we have not dispatched any embassy to the Courts and Governments of friendly countries. We have thought fit to select our trusted and honored minister, Iwakura Tomomi, the Junior Prime Minister (“ udaijin”), as Ambassador Extraordinary … and invested [him] with full powers to proceed to the Government of the United States, as well as to other Governments, in order to declare our cordial friendship, and to place the peaceful relations between our respective nations on a firmer and broader basis.

“The period for revising the treaties now existing between ourselves and the United States is less than one year distant. We expect and intend to reform and improve the same so as to stand upon a similar footing with the most enlightened nations, and to attain the full development of public rights and interest. The civilization and institutions of Japan are so different from those of other countries that we cannot expect to reach the declared end at once. It is our purpose to select from the various institutions prevailing among enlightened nations such as are best suited to our present conditions, and adapt them in gradual reforms and improvements of our policy and customs so as to be upon an equality with them. With this object we desire to fully disclose to the United States Government the constitution of affairs in our Empire, and to consult upon the means of giving greater efficiency to our institutions at present and in the future, and as soon as the said Embassy returns home we will consider the revision of the treaties and accomplish what we have expected and intended.

Your affectionate brother and friend,

Signed Mutsuhito

Countersigned Sanjō Sanetomi, Prime Minister

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: William fallows, Smithsonian magazine; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016