MEIJI RESTORATION

Meiji Emperor

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “The events that toppled the bakufu are known collectively as the Meiji Restoration because, in theory at least, the emperor had been "restored" to his rightful place as Japan’s actual head of state (the last time a roughly similar "restoration" of the emperor had taken place was 1333). The name that the emperor’s handlers selected for his reign was "Meiji," which means something like "enlightened rule." [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“By the early 1860s, a rough consensus had developed, shared even by many bakufu officials and allies, that major changes would be necessary were Japan to avoid China’s fate at the hands of foreign imperialists. The shogun sought to preserve a major role for the Tokugawa family in the new order, but bakufu opponents would settle for nothing less than his complete retirement from official life. Warfare on a relatively small scale broke out over this issue during the last months of 1867 and the first months of 1868. When the shogun realized that he lacked sufficient support to prevail, he surrendered peacefully to prevent large-scale loss of life. He received a generous financial settlement from the new government and went into retirement. The Tokugawa family still maintains a cultural foundation to preserve important historical documents and artifacts and to promote research. ~

“As time went on, the emperor became a tremendously potent symbol of Japan as a nation. So awesome and lofty had he grown by the late 1930s, that it became illegal for ordinary people even to look at him directly. Precisely because of their lofty statuses, however, Japan’s modern emperors did not administer the country directly. Had they done so, they would have appeared too human and too fallible. When things went poorly, prime ministers and cabinet members could resign, and the emperor remained above the level of overt political struggle. When things went well, the emperor could and did share in the glory. For the most part, Japan’s modern emperors have been relatively passive sovereigns, content to follow the lead of their advisors.” ~

Meiji Empress Websites and Sources: Meiji Period: Images of the Westernization of Japan MIT Visualizing Culture ; Wikipedia article on the Meiji Restoration Wikipedia ; Essay on Meiji Restoration aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; 1889 Constitution history.hanover.edu/texts Meiji Taisho http://www.meijitaisho.net Perry’s Visits Japan A Visual History brown.edu/japan/images ; Black Ships and Samurai MIT Visualizing Culture ; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ;

Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia

Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; PERRY, BLACK SHIPS AND JAPAN OPENS UP factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) EMPEROR, LEADERS AND STATE SHINTO factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) REFORMS, MODERNIZATION AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; MEIJI CONSTITUTION factsanddetails.com; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “Meiji Restoration Losers: Memory and Tokugawa Supporters in Modern Japan (Harvard East Asian Monographs)” by Michael Wert Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan” by John Whitney Hall (Editor), James L. McClain Amazon.com; “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912" Illustrated (2005) by Donald Keene Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan” by Christopher Benfey (Random House, 2003) Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “Breaking Open Japan: Commodore Perry, Lord Abe, and American Imperialism in 1853" by George Feifer Amazon.com; “Japan before Perry: A Short History” by Conrad Totman Amazon.com; “The First European Description of Japan, 1585" by Luis Frois Amazon.com;

Events Leading up to the Meiji Restoration

The 15 year period (1853 and 1868) between the arrival of Perry's Black Ships and the Meiji Restoration was characterized by social unrest, assassinations, conspiracies, alliances, broken alliances, treacheries and chaos. Sawa Kurotani wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: The turbulent period toward the end of the 19th century, when the long rule of the Tokugawa shogunate collapsed and political control of Japan was "returned" to the emperor, represents another moment of upheaval when established social order broke down and competing world views clashed against one another. Key actors of this era, such as Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Sakamoto Ryoma and Saigo Takamori, had to set aside ingrained prejudices, shake hands with age-old enemies and embrace foreign ideas and new technologies to strengthen a newly emerging nation. They had also forsaken their personal well-being and ignored individual gain for the sake of a larger cause. [Source: Sawa Kurotani, Daily Yomiuri, December 27, 2011]

Three days after Perry's arrival Shogun Ieyoshi died and was replaced by the feeble-minded Shogun Iesada, who signed a second treaty, without the endorsement of the emperor, promising foreigners a favorable exchange rate and an exemption from Japanese law.

In Kyoto, feudal lords began turning their backs on the weakening Tokugawa shogunate. Anti-foreigner pro-government and pro-Emperor factions began confronting each other. Samurai were often the targets. Their bodies were found in the streets and their houses were burned. A group of young fiercely loyal samurai called the Shinsengumi were called in by the shogun to restore order, which they were able to do to some degree by murdering anyone accused of opposing the shogun.

Impact of Admiral Perry’s Visit

Yoshida Shoin heading to the Black Ships

The Shogunate was significantly damaged by the visit of Perry’s Black Ships. Debate over government policy was unusual and had engendered public criticism of the Shogunate. In the hope of enlisting the support of new allies the Shogun had consulted with the shinpan and tozama daimyo, further undermining the already weakened Shogunate. In the Ansei Reform (1854-56), Shogun Abe then tried to strengthen the regime by ordering Dutch warships and armaments from the Netherlands and building new port defenses. In 1855 a naval training school with Dutch instructors was set up at Nagasaki, and a Western-style military school was established at Edo; by the next year, the government was translating Western books. Opposition to Abe increased within fudai circles, which opposed opening Shogunate councils to tozama daimyo, and he was replaced in 1855 as chairman of the senior councillors by Hotta Masayoshi (1810-64). [Source: Library of Congress *]

At the head of the dissident faction was Tokugawa Nariaki, who had long embraced a militant loyalty to the emperor along with antiforeign sentiments, and who had been put in charge of national defense in 1854. The Mito school — based on neo-Confucian and Shinto principles — had as its goal the restoration of the imperial institution, the turning back of the West, and the founding of a world empire under the divine Yamato Dynasty. *

In the final years of the Tokugawa, foreign contacts increased as more concessions were granted. The new treaty with the United States in 1859 allowed more ports to be opened to diplomatic representatives, unsupervised trade at four additional ports, and foreign residences in Osaka and Edo. It also embodied the concept of extraterritoriality (foreigners were subject to the laws of their own countries but not to Japanese law). Hotta lost the support of key daimyo, and when Tokugawa Nariaki opposed the new treaty, Hotta sought imperial sanction. The court officials, perceiving the weakness of the Shogunate, rejected Hotta's request and thus suddenly embroiled Kyoto and the emperor in Japan's internal politics for the first time in many centuries. When the shogun died without an heir, Nariaki appealed to the court for support of his own son, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (or Keiki), for shogun, a candidate favored by the shinpan and tozama daimyo. The fudai won the power struggle, however, installing Tokugawa Yoshitomi, arresting Nariaki and Keiki, executing Yoshida Shoin (1830-59, a leading sonno-joi intellectual who had opposed the American treaty and plotted a revolution against the Shogunate), and signing treaties with the United States and five other nations, thus ending more than 200 years of exclusion. *

The strong measures the Shogunate took to reassert its dominance were not enough. Revering the emperor as a symbol of unity, extremists wrought violence and death against the Shogunate and han authorities and foreigners. Foreign naval retaliation led to still another concessionary commercial treaty in 1865, but Yoshitomi was unable to enforce the Western treaties. A Shogunate army was defeated when it was sent to crush dissent in Satsuma and Choshu han in 1866. Finally, in 1867, the emperor died and was succeeded by his minor son Mutsuhito; Keiki reluctantly became head of the Tokugawa house and shogun. He tried to reorganize the government under the emperor while preserving the shogun's leadership role. Fearing the growing power of the Satsuma and Choshu daimyo, other daimyo called for returning the shogun's political power to the emperor and a council of daimyo chaired by the former Tokugawa shogun. Keiki accepted the plan in late 1867 and resigned, announcing an "imperial restoration." The Satsuma, Choshu, and other han leaders and radical courtiers, however, rebelled, seized the imperial palace, and announced their own restoration on January 3, 1868. The Shogunate was abolished, Keiki was reduced to the ranks of the common daimyo, and the Tokugawa army gave up without a fight (although other Tokugawa forces fought until November 1868, and Shogunate naval forces continued to hold out for another six months). *

Earthquakes and the Disasters in the Ansei Era (1854-1860)

Ansei earthquake (Kashima controls Namazu, the earthquake-causing fish)

Masayuki Yamauchi is a professor at the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Arts and Science, wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “During the Ansei era (1854-1860), a host of devastating earthquakes and epidemics occurred, compounded by domestic political crises, forcing the political leaders of the day to rise to challenges. In 1854, the first year of the Ansei era, when the Tokugawa shogunate bowed to Commodore Matthew Perry in opening Japan to the United States, the Great Tokai Earthquake and the Great Nankai Earthquake, both magnitude-8 tremors, and the magnitude-7.4 Great Hoyo Earthquake occurred, causing terrible tsunami damage to Pacific coastal areas. In October 1855, the magnitude-6.9 Ansei Edo Great Earthquake battered the capital. One of its most prominent victims was Fujita Toko, a senior Mito domain official, who was crushed to death. Yet, this temblor was smaller than the magnitude-7.4 quake that rocked the Iga Ueno area — now in Mie Prefecture — in June 1854.” [Source: Masayuki Yamauchi, Yomiuri Shimbun. May 8, 2011 ]

“In 1856, a typhoon swept through the Izu Peninsula and the northern parts of Edo, now Tokyo, causing widespread floods along the Tonegawa and Arakawa rivers, killing about 100,000 people. An influenza epidemic in 1857 was followed by cholera epidemic that claimed the lives of 100,000 to 300,000 people. The cholera was brought to Japan by a U.S. naval fleet. In 1859, a large number of people died from a measles outbreak, an event known as the Great Ansei Mashin (measles).

“In the face of these calamities, the Ansei "prime ministers" of the shogunate, Abe Masahiro and Hotta Masayoshi, did not hesitate to pick up the gauntlet with extraordinary resolution and courage. Hotta assumed the post of chief of the Council of Elders (roju) — ranking immediately below the shogun — only a week after the 1855 Edo earthquake and started tackling a series of internal and external difficulties.

“Even before taking up his new post, Hotta ordered shelters erected for quake victims two days after the earthquake, had emergency kitchens provide food and ordered emergency rice distribution. By today's standards, he acted extremely swiftly...The Tokugawa shogunate, however, continued to weaken as it was forced to carry out emergency fiscal spending to finance disaster reconstruction. If the Ansei streak of calamities had not occurred, the shogunate might not have helplessly yielded to the alliance of the rebellious Satsuma and Choshu domains, both of which suffered almost no damage from the natural catastrophes. By extension, measures taken against disasters and reconstruction efforts elsewhere would have imposed political challenges so serious they could have upended any regime.”

Yoshida Shoin

Yoshida Shion

Japan's transformation from feudal society to a modern nation in the 19th century was brought about in part by a bold action taken by Yoshida Shoin, a samurai teacher who rowed a small boat out to Perry's warship and asked the commodore if he could be taken to America so he could study Western technology. At that time leaving Japan was a crime punishable by death. Perry refused to take him; Yoshida was imprisoned but released a short while later. [Source: N. Taylor Gregg, National Geographic, June 1984]

Yoshida was a short, energetic and charismatic leader with a following of young men that devoted their lives to him with samurai-like intensity. He also some rather odd habits. He used to keep himself awake at night so he could study by putting mosquitoes in the sleeves of his kimono.

Yoshida and other Japanese were outraged by the treaty and the fact that samurai society had disintegrated into impoverished class of soldiers and a few rich and corrupt lords. Yoshida decided to take action to save his country.

Yoshida rallied his students to support his cause and formed a political organization, committed to overthrowing the shogun. He also set up a private school that taught young samurai. Among his students were Hirobumi Ito and Aritomo Yamagata, both future prime ministers and major player in the Meiji reforms.

After Yoshida was released from prison he returned to his hometown Hagi, where he developed a plan to assassinate a shogunate official but talked so much about it, word leaked out and was arrested again. This time he was beheaded, at the age of 29, in 1859. Although he was dismal failure as a rebellion leader he was good at inspiring others.

Rebellions Before the Meiji Restoration

Almost a decade after Yoshida execution, his students, allied with disenchanted samurai and other rebels committed to modernizing Japan, led a rebellion against the Tokugawa shogunate to restore power to the Emperor, who by this time had lost so much power and was so obscure most Japanese didn't even know he existed.

All of Japan at this time was in turmoil. Inflation was spinning out of control; the price of rice seemed to rise on a daily basis; the poor looted stores; and the rallying cry of the masses of was — Eijanaika — (“Why Not?”)

A militia of peasants led by Yoshida Shion's followers took over the Hagi government. The Western powers backed the new government. The rebellion was carried out in part with covertly-purchased weapons used in the American Civil War. When the shogunate's army moved against it was defeated.

Another rebel movement arose in Kagoshima. Hagi and Kagoshima were two areas of unrest during this period. Forces in Kagoshima were led by the Satsuma clan and those in Hagi were led by the Choshu clan. Satsuma and Choshu both describe places under the rule of one daimyo and the clan the daimyo ruled over.

Satsuma and Choshu had traditionally been enemies. In 1867, they united and routed the shogunate's army. The Tokugawa shogun announced the return of political power to the emperor but this move was superficial and didn’t satisfy anyone. Reformers were not pleased because the reforms didn't go far enough. The Tokugawa shogun hoped to return of power by controlling the emperor. Satsuma and Choshu hoped to gain of power by controlling the emperor

Boshin Civil Wars

The Boshin Civil War, which began after power had been returned to the Emperor, was an 18-month struggle between the western rebel clans, fighting in the name of the Emperor and led by Satsuma and Choshu, , and the Tokugawa shogunate, which had its power bases in the east and hoped to regain power with Emperor as its puppet.

The Boshin Civil War was primarily a series of major battles. It can be seen as struggle to gain control of the Emperor after it was decided to restore power to the Emperor. The first battle took place in Kyoto.

In the last battle of the Boshin War — the last major battle involving samurai — uniformed troops loyal to the Emperor, armed with latest rifles from England and France, fought against Tokugawa samurai armed with swords and muskets and dressed in traditionally samurai armor. The samurai were routed. The rebels defeated 15,000 shogunate troops and forced the 32-year-old Tokugawa shogun to flee to Osaka castle. Thousands died.

The shogun was forced to retire to Mito, where he spent the rest indulging himself in his hobbies: polo-playing, photography and embroidery.

Sakamoto Ryoma and the End of the Shogunate

Ryoma in 1867

Sakamoto Ryoma (1836-1867) was an important figure in the period before the Meiji Restoration. He is credited with bringing together the Kagoshima-based Satsuma clan and its traditional enemy, the Hagi-based Choshu clan. The son of a low-ranking samurai from Kochi on Shikoku, he reportedly wet his bed and cried as lot as a boy and was toughened up after learning kendo at a martial arts school. An NHK Sunday drama on the pre-Meji period hero Sakamoto Ryoma was watched religiously by a large number of people and set off a whole tourism industry of people visiting places highlighted in the show.

When he was 17, Sakamoto witnessed the arrival of Perry’s black ships. The event left a great impression on him. He later studied with Kawada Shoryo, a scholar who wrote a book about Nakahama Manjiro, the shipwrecked Japanese fishermen who was rescued by an American whaling ship and was educated in America.

Sakamoto learned about American democracy and found that system far preferable to the system in Japan, which favored upper classes at the expense of the lower classes. In 1861, Sakamoto joined the Tosa Loyalist Party along with other Tosa samurai who pledged to unite Japan under the Emperor. He later merged this loyalty with the belief that Japan needed to be modernized and Westernized.

In Sakamoto brokered the alliance between the Satsuma and Choshu clans, creating a force as strong as the shogun’s military, and creating the framework for the negotiated settlement for the return of political power to Emperor Meiji.

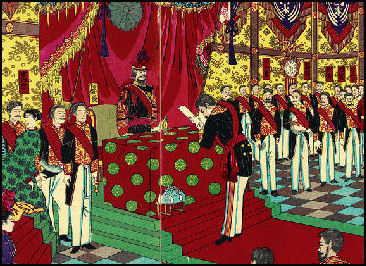

Meiji Restoration

The Japanese refer to rebellions that ousted the Tokugawa shogunate and restored power to the Emperor as the Meiji Restoration. Restoration is soft word. The events that unfolded would be better described as a full-blown revolution.

In 1868, the 15-year-old Emperor Mutsuhito was restored to the imperial throne. Mutsuhito was a member of the House of Yamato as were previous emperors. When he regained power as Emperor he assumed the name of "Meiji" ("enlightened government"). The event is referred to as the Meiji Restoration because it marked the restoration of the emperor as political power in Japan.

The restoration did not bring about direct rule of the Emperor. Rather it allowed an oligarchy made of loyalists who overthrew the shogunate to take power. Although they gained support for their cause by promising to expel foreigners they quickly became pragmatic after taking power and embraced foreign models for their reforms.

Those people who wanted to end Tokugawa rule did not envision a new government or a new society; they merely sought the transfer of power from Edo to Kyoto while retaining all their feudal prerogatives. Instead, a profound change took place. The emperor emerged as a national symbol of unity in the midst of reforms that were much more radical than had been envisioned. [Source: Library of Congress]

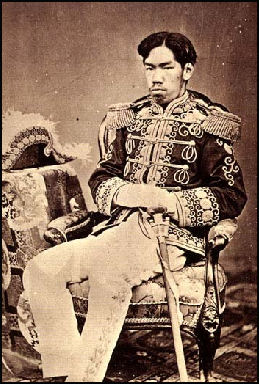

Meiji Emperor

Mutsohito, the Meiji Emperor, was Japan's first constitutional monarch. His reign from 1868 to 1912 defined the Meiji Period (1868-1912). As is true with most Japanese emperors little is known about his life. Much of what is known about has been gleaned from the 100,000 pieces of poetry he wrote.

Meiji Emperor in 1872

Mutsohito was born and grew up in Kyoto. He was given a traditional education, steeped in tanka poetry and calligraphy and the manners of the Imperial court. When he became Emperor at the age of 15 he moved from Kyoto into a new Imperial Palace in Tokyo and replaced his 10th century robes with a German-style military uniform. He fulfilled the Meiji reformers vision of a new emperor by becoming an active and visible monarch and playing a symbolic role as a military leader.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Although the Meiji emperor was not a puppet, he had little interest in the tedious details of statecraft and government administration and was happy for others to take care of such matters. He trusted the leaders of the Meiji Restoration and typically went along with whatever policies they worked out. For their part, the Meiji leaders positioned themselves to speak in the emperor’s name. They repeatedly portrayed the emperor as personifying and standing for "Japan" as a nation—still a terribly abstract entity, at a time when relatively few "Japanese" were accustomed to thinking of themselves as "Japanese." Leading government officials, therefore, when representing the emperor’s views (accurately or otherwise), positioned themselves on the side of the nation itself. This rhetorical and symbolic use of the emperor as a political weapon was often highly effective. It was relatively easy for the state to cast anyone who fundamentally opposed the new Meiji state, or subsequent Japanese governments, in the role of an enemy of the emperor and nation. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org]

It is not exactly known how much input Emperor Meiji had on the decisions that were made with his signature during his reign. As Emperor he enjoyed riding and drinking and was known as a womanizer and a hard worker with a lively sense of humor and a sadistic streak and a tendency towards nervousness. He once dropped a piece of asparagus just to observe his chamberlain pick it up and was known for fumbling speeches around foreigners.

Book: "Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912" by Donald Keene (Columbia University Press, 2002)

Meiji Leadership

Saigo Takamori

The Meiji oligarchy, as the new ruling class is known to historians, was a privileged clique that exercised imperial power, sometimes despotically. The members of this class were adherents of kokugaku and believed they were the creators of a new order as grand as that established by Japan's original founders. Two of the major figures of this group were Okubo Toshimichi (1832-78), son of a Satsuma retainer, and Satsuma samurai Saigo Takamori (1827-77), who had joined forces with Choshu, Tosa, and Hizen to overthrow the Tokugawa. Okubo became minister of finance and Saigo a field marshal; both were imperial councillors. Kido Koin (1833- 77), a native of Choshu, student of Yoshida Shoin, and coconspirator with Okubo and Saigo, became minister of education and chairman of the Governors' Conference and pushed for constitutional government. Also prominent were Iwakura Tomomi (1825-83), a Kyoto native who had opposed the Tokugawa and was to become the first ambassador to the United States, and Okuma Shigenobu (1838-1922), of Hizen, a student of Rangaku, Chinese, and English, who held various ministerial portfolios, eventually becoming prime minister in 1898. [Source: Library of Congress]

To accomplish the new order's goals, the Meiji oligarchy set out to abolish the Tokugawa class system through a series of economic and social reforms. Shogunate revenues had depended on taxes on Tokugawa and other daimyo lands, loans from wealthy peasants and urban merchants, limited customs fees, and reluctantly accepted foreign loans. To provide revenue and develop a sound infrastructure, the new government financed harbor improvements, lighthouses, machinery imports, schools, overseas study for students, salaries for foreign teachers and advisers, modernization of the army and navy, railroads and telegraph networks, and foreign diplomatic missions.

Toshimichi Okubo

Toshimichi Okubo (1830-78), one of the most influential leaders of the Meiji Restoration, wrote, "A state of great disorder reigns over the country, as no genuine rule of law has been established yet and everyone is trying to usurp power...People demand whatever they please, but the government is at a loss to control them. As a result, it is yielding to them submissively."

Toshimichi Okubo

“Based on this situation, Okubo made up his mind to proceed with reforms,” Takashi Mikuriya, a professor of political science at the University of Tokyo, wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun. “To achieve the national goal of modernizing as quickly as possible, the country first had to establish a steadfast governing system. To that end, Okubo repeatedly advised the new regime — whose members kept behaving like a flock of sheep without shepherds — to impose an obligation of secrecy and define the chain of command, i.e., the line of authority and responsibility.” [Source: Takashi Mikuriya, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 1, 2011]

“In the same context, Okubo proposed that the governing system be established by distinguishing between "mass deliberation" and "public opinion," while giving due consideration to the adoption of "abnormal and irregular systems" or "normal and regular systems" as required. His proposal meant that the undisciplined regime should first shape "public opinion" — which would outline what the country should be in the future — out of irresponsible and vacillating rounds of "mass deliberation."

It also meant the government should implement "abnormal and irregular systems" that could bring about quicker results whenever necessary — without forgetting the importance of "normal and regular systems" as its higher ideal. Thanks to the Restoration government's "leap of death" as described by the late University of Tokyo Prof. Sato in his book "'Shi no Choyaku' wo Koete’seiyo no Shogeki to Nippon" ("Beyond the 'Leap of Death' — the Impact of the West and Japan"), the country became Asia's first modern nation state.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016