MEIJI REFORMS

As part of the Meiji Reforms samurai were required to cut their topknots

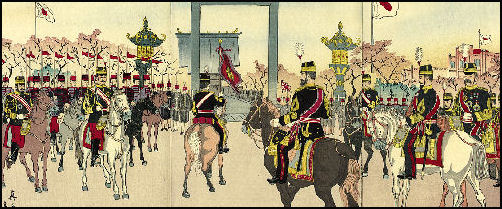

Difficult economic times, manifested by increasing incidents of agrarian rioting, led to calls for social reforms. In addition to the old high rents, taxes, and interest rates, the average citizen was faced with cash payments for new taxes, military conscription, and tuition charges for compulsory education. The people needed more time for productive pursuits while correcting social abuses of the past. To achieve these reforms, the old Tokugawa class system of samurai, farmer, artisan, and merchant was abolished by 1871, and, even though old prejudices and status consciousness continued, all were theoretically equal before the law. Actually helping to perpetuate social distinctions, the government named new social divisions: the former daimyo became nobility, the samurai became gentry, and all others became commoners. Additionally, between 1871 and 1873, a series of land and tax laws were enacted as the basis for modern fiscal policy. Private ownership was legalized, deeds were issued, and lands were assessed at fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Meiji reforms included requiring former samurai to cut their topknots (only sumo wrestlers were allowed to keep them); dismantling of castles; and moving of the Imperial capital from Kyoto to Edo and renaming it Tokyo (meaning "eastern capital"). In 1873, the Meiji government ordered the destruction of 144 castles, leaving only 39 left. Of these all but 12 were destroyed in World War II.

Meiji leaders "wisely grasped the essence of Western science and technology was based on analysis and empirical evidence, not moral axioms and seniority." Universities open to all citizens were established; a new education and banking system was adopted; and modern weaponry, trains and telegraphs were imported from the West. Telegraph cable links were established between all major Japanese cities and the Asian mainland and railroads, shipyards, munitions factories, mines, textile manufacturing facilities, factories, and experimental agriculture stations were built. On January 1, 1873, Japan finally adopted the Gregorian calendar which was used from then on side by side with the old system of the reign years of Emperors.

Much concerned about national security, the leaders made significant efforts at military modernization, which included establishing a small standing army, a large reserve system, and compulsory militia service for all men. Foreign military systems were studied, foreign advisers were brought in, and Japanese cadets sent abroad to European and United States military and naval schools. Japan's modern army was founded by Masujiro Omura, a general who took the revolutionary step of recruiting peasants and workers not just samurai. The members of the warrior class were not pleased. Omura was eventually assassinated by a group of samurai.

The Japanese feudal system was peacefully dissolved in 1868 and 1869, with the reformist government overseeing the buying up of land owned by daimyos, who were incorporating into the new imperial aristocracy. Daimyo land was divided into the prefectures that still exist today. Daimyo and samurai pensions were paid off in lump sums, and the samurai later lost their exclusive claim to military positions. Former samurai found new pursuits as bureaucrats, teachers, army officers, police officials, journalists, scholars, colonists in the northern parts of Japan, bankers, and businessmen. These occupations helped stem some of the discontent this large group felt; some profited immensely, but many were not successful and provided significant opposition in the ensuing years.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com;PERRY, BLACK SHIPS AND JAPAN OPENS UP factsanddetails.com; MEIJI RESTORATION: REBELLIONS, YOSHIDA SHION, SAKAMOTO RYOMA AND THE MEIJI EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) EMPEROR, LEADERS AND STATE SHINTO factsanddetails.com; MEIJI CONSTITUTION factsanddetails.com; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Meiji Period: Images of the Westernization of Japan MIT Visualizing Culture ; Wikipedia article on the Meiji Restoration Wikipedia ; Essay on Meiji Restoration aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; 1889 Constitution history.hanover.edu/texts Meiji Taisho http://www.meijitaisho.net Perry’s Visits Japan A Visual History brown.edu/japan/images ; Black Ships and Samurai MIT Visualizing Culture ; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ; Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912" Illustrated (2005) by Donald Keene Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “Meiji Restoration Losers: Memory and Tokugawa Supporters in Modern Japan (Harvard East Asian Monographs)” by Michael Wert Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan” by John Whitney Hall (Editor), James L. McClain Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan” by Christopher Benfey (Random House, 2003) Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “Breaking Open Japan: Commodore Perry, Lord Abe, and American Imperialism in 1853" by George Feifer Amazon.com; “Japan before Perry: A Short History” by Conrad Totman Amazon.com; “The First European Description of Japan, 1585" by Luis Frois Amazon.com;

Reducing the Power of the Daimyo and Samurai

Yamauchi Toyonori, an 19th century daimyo

In a move critical for the consolidation of the new regime, most daimyo voluntarily surrendered their land and census records to the emperor, symbolizing that the land and people were under the emperor's jurisdiction. Confirmed in their hereditary positions, the daimyo became governors, and the central government assumed their administrative expenses and paid samurai stipends. The han were replaced with prefectures in 1871, and authority continued to flow to the national government. Officials from the favored former han, such as Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa, and Hizen, staffed the new ministries. Formerly out-of-favor court nobles and lower-ranking but more radical samurai replaced Shogunate appointees, daimyo, and old court nobles as a new ruling class appeared. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Between 1868 and 1871, the new government inherited many of the bakufu’s assets and obligations. The bakufu, however, was essentially broke at the time of the restoration, so the Meiji government urgently needed additional revenue. The single largest financial burden was the payment of samurai stipends throughout all of Japan, for which the Meiji government became responsible in 1871. Therefore, the government moved to reduce or eliminated samurai stipends as soon as possible. Late in 1873, it began to tax stipends and allowed samurai the option of converting their stipends to a one-time, lump-sum payment. Few samurai selected this option.

In the summer of 1876, the Meiji government commuted all samurai stipends to intermediate-term government bonds. It distributed ¥174 million in bonds to roughly 313,000 individuals, which reduced government expenditures by 30 percent. By commuting the stipends to bonds, the new government also hoped that the samurai would have a stake in its survival. This move, combined with a phase out of samurai privileges and obligations essentially put an end to the samurai class by 1876, although the end was in sight as early as 1873. Many samurai did not do well on their own. For example, some sold their bonds at a discount to brokers and then invested their cash unwisely. During the 1870s discontent among the samurai or former samurai was a major source of civil discontent, which sometimes erupted in local rebellions against the Meiji government.

Foreign Influences During the Meiji Period

Meiji Emperor in a Prussian-style uniform

The Meiji oligarchy was aware of Western progress, and "learning missions" were sent abroad to absorb as much of it as possible. One such mission, led by Iwakura, Kido, and Okubo and containing forty-eight members in total, spent two years (1871-73) touring the United States and Europe, studying government institutions, courts, prison systems, schools, the import-export business, factories, shipyards, glass plants, mines, and other enterprises. [Source: Library of Congress]

The members of the delegation experienced culture shock in the United States and Britain and were unable to unravel the intricacies of American and British law and had trouble with other things like the button flies of the Western-style trousers the wore for the first time. Their visit to Germany, recently unified under Bismark, was more comforting. The Japanese saw Germany as a “new” country in a similar stage of development as their own country and were swayed by Bismark’s argument to build a strong military first and put their faith in that rather than “a naive faith in the law of nations.”

Upon returning, mission members called for domestic reforms that would help Japan catch up with the West. The revision of unequal treaties forced on Japan became a top priority. The returned envoys also sketched a new vision for a modernized Japan's leadership role in Asia, but they realized that this role required that Japan develop its national strength, cultivate nationalism among the population, and carefully craft policies toward potential enemies. No longer could Westerners be seen as "barbarians," for example. In time, Japan formed a corps of professional diplomats. [Source: Library of Congress]

Germany was the primary model. German language and literature were taught n elite schools not English or France, fascination with Germany also reached the masses. An 1887 magazine article read; “O blow thou German wind! Your approach is felt in scholarship, in the military, in student’s caps, in beer — though why you blow I don know.”

Development of Representative Government in Japan

Japanese House of Peers

The major institutional accomplishment after the Satsuma Rebellion was the start of the trend toward developing representative government. People who had been forced out or left out of the governing apparatus after the Meiji Restoration had witnessed or heard of the success of representative institutions in other countries of the world and applied greater pressure for a voice in government.[Source: Library of Congress]

A major proponent of representative government was Itagaki Taisuke (1837-1919), a powerful leader of Tosa forces who had resigned from his Council of State position over the Korean affair in 1873. Itagaki sought peaceful rather than rebellious means to gain a voice in government. He started a school and a movement aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy and a legislative assembly. Itagaki and others wrote the Tosa Memorial in 1874 criticizing the unbridled power of the oligarchy and calling for the immediate establishment of representative government. Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha (Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878. In 1881, in an action for which he is best known, Itagaki helped found the Jiyuto (Liberal Party), which favored French political doctrines. In 1882 Okuma established the Rikken Kaishinto (Constitutional Progressive Party), which called for a British-style constitutional democracy. In response, government bureaucrats, local government officials, and other conservatives established the Rikken Teiseito (Imperial Rule Party), a progovernment party, in 1882. Numerous political demonstrations followed, some of them violent, resulting in further government restrictions. The restrictions hindered the political parties and led to divisiveness within and among them. The Jiyuto, which had opposed the Kaishinto, was disbanded in 1884, and Okuma resigned as Kaishinto president. *

19th century Japanese Parliament

Government leaders, long preoccupied with violent threats to stability and the serious leadership split over the Korean affair, generally agreed that constitutional government should someday be established. Kido had favored a constitutional form of government since before 1874, and several proposals that provided for constitutional guarantees had been drafted. The oligarchy, however, while acknowledging the realities of political pressure, was determined to keep control. Thus, modest steps were taken. The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Council of Elders (Genronin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature. The emperor declared that "constitutional government shall be established in gradual stages" as he ordered the Council of Elders to draft a constitution. Three years later, the Conference of Prefectural Governors established elected prefectural assemblies. Although limited in their authority, these assemblies represented a move in the direction of representative government at the national level, and by 1880 assemblies also had been formed in villages and towns. In 1880 delegates from twenty-four prefectures held a national convention to establish the Kokkai Kisei Domei (League for Establishing a National Assembly). *

Although the government was not opposed to parliamentary rule, confronted with the drive for "people's rights," it continued to try to control the political situation. New laws in 1875 prohibited press criticism of the government or discussion of national laws. The Public Assembly Law (1880) severely limited public gatherings by disallowing attendance by civil servants and requiring police permission for all meetings. Within the ruling circle, however, and despite the conservative approach of the leadership, Okuma continued as a lone advocate of British-style government, a government with political parties and a cabinet organized by the majority party, answerable to the national assembly. He called for elections to be held by 1882 and for a national assembly to be convened by 1883; in doing so, he precipitated a political crisis that ended with an 1881 imperial rescript declaring the establishment of a national assembly in 1890 and dismissing Okuma. *

Ito Hirobumi and the Prussian Model of Government for Japan

Rejecting the British model, Iwakura and other conservatives borrowed heavily from the Prussian constitutional system. One of the Meiji oligarchy,Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909), a Choshu native long involved in government affairs, was charged with drafting Japan's constitution. He led a Constitutional Study Mission abroad in 1882, spending most of his time in Germany. He rejected the United States Constitution as "too liberal" and the British system as too unwieldy and having a parliament with too much control over the monarchy; the French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism. [Source: Library of Congress *]

On Ito’s return, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Five hundred persons from the old court nobility, former daimyo, and samurai who had provided valuable service to the emperor were organized in five ranks: prince, marquis, count, viscount, and baron. Ito was put in charge of the new Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems in 1884, and the Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Ito as prime minister. The positions of chancellor, minister of the left, and minister of the right, which had existed since the seventh century as advisory positions to the emperor, were all abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution and to advise the emperor. To further strengthen the authority of the state, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922), a Choshu native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional prime minister. The Supreme War Council developed a German-style general staff system with a chief of staff who had direct access to the emperor and who could operate independently of the army minister and civilian officials. *

When finally granted by the emperor as a sign of his sharing his authority and giving rights and liberties to his subjects, the 1889 Constitution of the Empire of Japan (the Meiji Constitution) provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who paid ¥15 in national taxes, about 1 percent of the population; the House of Peers, composed of nobility and imperial appointees; and a cabinet responsible to the emperor and independent of the legislature. The Diet could approve government legislation and initiate laws, make representations to the government, and submit petitions to the emperor. Nevertheless, in spite of these institutional changes, sovereignty still resided in the emperor on the basis of his divine ancestry. The new constitution specified a form of government that was still authoritarian in character, with the emperor holding the ultimate power and only minimal concessions made to popular rights and parliamentary mechanisms. Party participation was recognized as part of the political process. The Meiji Constitution was to last as the fundamental law until 1947. *

Meiji government

The first national election was held in 1890, and 300 members were elected to the House of Representatives. The Jiyuto and Kaishinto parties had been revived in anticipation of the election and together won more than half of the seats. The House of Representatives soon became the arena for disputes between the politicians and the government bureaucracy over large issues, such as the budget, the ambiguity of the constitution on the Diet's authority, and the desire of the Diet to interpret the "will of the emperor" versus the oligarchy's position that the cabinet and administration should "transcend" all conflicting political forces. The main leverage the Diet had was in its approval or disapproval of the budget, and it successfully wielded its authority henceforth. *

In the early years of constitutional government, the strengths and weaknesses of the Meiji Constitution were revealed. A small clique of Satsuma and Choshu elite continued to rule Japan, becoming institutionalized as an extraconstitutional body of genro (elder statesmen). Collectively, the genro made decisions reserved for the emperor, and the genro, not the emperor, controlled the government politically. Throughout the period, however, political problems were usually solved through compromise, and political parties gradually increased their power over the government and held an ever larger role in the political process as a result. Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as prime minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genro who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives. Although not fully realized, the trend toward party politics was well established. *

Meiji Period Government Changes

The Japanese parliamentary system was the first of its kind in Asia. Japan’s first general election was held in 1890 but it didn’t produce much lasting effect. Japan’s reborn imperial system was largely German-derived. State-Shintoism was a response to Western Christianity. The Diet was created by an Imperial edict by the Meiji Emperor in October 1891. With the first Imperial diet opening after the first elections of the House of representative in July the same year.

Many pre-World-War-II Japanese ideas about nationalism, armed strength, authoritarian rule, territorial expansion and militarism have their roots in Germany. The military was reformed on the Prussian model of modernity: Japan adopted a Civil Code, Commercial Code and bunch of other laws influenced by Germany and France.

The Meiji leaders also modernized foreign policy, an important step in making Japan a full member of the international community. The traditional East Asia worldview was based not on an international society of national units but on cultural distinctions and tributary relationships. Monks, scholars, and artists, rather than professional diplomatic envoys, had generally served as the conveyors of foreign policy. Foreign relations were related more to the sovereign's desires than to the public interest. For Japan to emerge from the feudal period, it had to avoid the fate of other Asian countries by establishing genuine national independence and equality. [Source: Library of Congress]

By the 1890s, government leaders were worried about the influence of too much Westernization and supported a return to traditional Japanese values.

Westernization and Modernization in the Meiji Period

The Meiji Era was one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of nations. Japan advanced from a rural society ruled by hereditary landowners to an industrialized economic power dominated by educated bureaucrats, achieving in decades what the nations of the West took centuries to develop — a modern nation with modern industries, modern political institutions and a modern society.

Japan resisted the power and hegemony of the West by emulating the West. Under the slogan "rich country, strong military," the Japanese government was intent on learning the secrets of the West and Western experts were brought to Japan and Japanese experts were sent aborad to learn everything they could.

The initial motivations behind the Meiji Period were xenophobia and anti-Western sentiments. The Japanese sought Western technology and modernized essentially to level the playing field so they would not be colonized or taken advantage of by the West. When U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant visited Japan in 1879. During the trip he was particularly impressed by a Noh performance he saw and said Japan must takes pains not to modernize too quickly and lose its traditions.

As part of the "Japanese spirit, Western knowledge" effort, Japanese began wearing European-style army uniforms, mourning coats, top hats and ball gowns. Members of the Imperial court adopted European titles and rococo, neo classical building were raised and concerts of Western classical music were performed. The Japanese built a British-style navy, French-style bureaucracy and established a Prussian-style constitution. Japanese intellectuals discussed French poetry and English novels, There was even a serious debates in the education ministry about changing the national language to English.

Economic Modernization and Industrialization in the Meiji Period

When Japan began to modernize after the Meiji Restoration it produced only one major product for export: silk. By using machinery to both upgrade the quality and quantity of silk produced Japan became the world’s largest exporter of silk in 1909. Much of the foreign currency earned from silk was used to beef up the Japanese navy.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa-Meiji transition as the first Asian industrialized nation. Domestic commercial activities and limited foreign trade had met the demands for material culture in the Tokugawa period, but the modernized Meiji era had radically different requirements. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. The private sector — in a nation blessed with an abundance of aggressive entrepreneurs — welcomed such change. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. Establishment of a modern institutional framework conducive to an advanced capitalist economy took time but was completed by the 1890s. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons. Many of the former daimyo, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries. Those who had been informally involved in foreign trade before the Meiji Restoration also flourished. Old Shogunate-serving firms that clung to their traditional ways failed in the new business environment. *

The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. After the first twenty years of the Meiji period, the industrial economy expanded rapidly until about 1920 with inputs of advanced Western technology and large private investments. Stimulated by wars and through cautious economic planning, Japan emerged from World War I as a major industrial nation.*

Meiji Era Industrialization Recognized by UNESCO

Nirayama-Hansharo

In 2015, “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining” were designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites. According to UNESCO: “The site encompasses a series of twenty three component parts, mainly located in the southwest of Japan. It bears testimony to the rapid industrialization of the country from the middle of the 19th century to the early 20th century, through the development of the iron and steel industry, shipbuilding and coal mining. The site illustrates the process by which feudal Japan sought technology transfer from Europe and America from the middle of the 19th century and how this technology was adapted to the country’s needs and social traditions. The site testifies to what is considered to be the first successful transfer of Western industrialization to a non-Western nation. [Source: UNESCO]

“A series of industrial heritage sites, focused mainly on the Kyushu-Yamaguchi region of south-west of Japan, represent the first successful transfer of industrialization from the West to a non-Western nation. The rapid industrialization that Japan achieved from the middle of the 19th century to the early 20th century was founded on iron and steel, shipbuilding and coal mining, particularly to meet defence needs. The sites in the series reflect the three phases of this rapid industrialisation achieved over a short space of just over fifty years between 1850s and 1910.

“The first phase in the pre-Meiji Bakumatsu isolation period, at the end of Shogun era in the 1850s and early 1860s, was a period of experimentation in iron making and shipbuilding. Prompted by the need to improve the defences of the nation and particularly its sea-going defences in response to foreign threats, industrialisation was developed by local clans through second hand knowledge, based mostly on Western textbooks, and copying Western examples, combined with traditional craft skills. Ultimately most were unsuccessful. Nevertheless this approach marked a substantial move from the isolationism of the Edo period, and in part prompted the Meiji Restoration.

“The second phase from the 1860s accelerated by the new Meiji Era, involved the importation of Western technology and the expertise to operate it; while the third and final phase in the late Meiji period (between 1890 to 1910), was full-blown local industrialization achieved with newly-acquired Japanese expertise and through the active adaptation of Western technology to best suit Japanese needs and social traditions, on Japan’s own terms. Western technology was adapted to local needs and local materials and organised by local engineers and supervisors.

Big Crane at Mitsubishi Dock Yard in Nagasaki

The 23 components are in 11 sites within 8 discrete areas. Six of the eight areas are in the south-west of the country, with one in the central part and one in the northern part of the central island. Collectively the sites are an outstanding reflection of the way Japan moved from a clan based society to a major industrial society with innovative approaches to adapting western technology in response to local needs and profoundly influenced the wider development of East Asia. After 1910, many sites later became fully fledged industrial complexes, some of which are still in operation or are part of operational sites.

“The Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution illustrate the process by which feudal Japan sought technology transfer from Western Europe and America from the middle of the 19th century and how this technology was adopted and progressively adapted to satisfy specific domestic needs and social traditions, thus enabling Japan to become a world-ranking industrial nation by the early 20th century. The sites collectively represents an exceptional interchange of industrial ideas, know-how and equipment, that resulted, within a short space of time, in an unprecedented emergence of autonomous industrial development in the field of heavy industry which had profound impact on East Asia.

“The technological ensemble of key industrial sites of iron and steel, shipbuilding and coal mining is testimony to Japan’s unique achievement in world history as the first non-Western country to successfully industrialize. Viewed as an Asian cultural response to Western industrial values, the ensemble is an outstanding technological ensemble of industrial sites that reflected the rapid and distinctive industrialisation of Japan based on local innovation and adaptation of Western technology.”

Culture and Life in the Meiji Period

The Japanese government was also committed to improving the quality of life for all Japanese. At time of Meiji takeover, 50 percent of boys and 15 percent of girls could read and write, by 1908 primary education was universal and the majority of Japanese children of both sexes could read and write.

The Meiji Period also resulted in the revival of traditional Imperial art forms such as waka and haiku poetry and nurtured an interest in Western painting and sculpture. Japanese culture also made its way west. Westerners were excited about buying silks and porcelains in the 1880s. Artist like Van Gogh and Gauguin were inspired by Japanese art.

One of Japan’s biggest exports in this period was prostitutes. By some counts 20,000 to 30,000 Japanese girls left home between the early Meiji period and World War II to work as prostitutes in China, Southeast Asia, India, Siberia and even Africa. Many were illiterate girls from poor families who were deceived into providing the girls by gangsters and essentially became indebted sexual servants.. A farmer in Borneo told the Daily Yomiuri. “They were very beautiful in their kimono, and they wore lots of make up. People like us farmers could not afford Japanese prostitutes. White men got the prettiest ones, followed by the Chinese coolies from plantations, because they had money and were bachelors.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016