MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912)

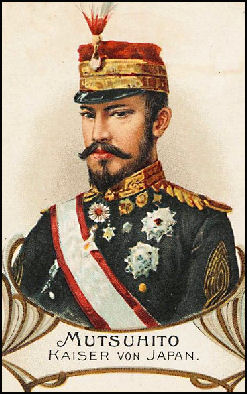

Meiji Emperor

The Meiji Period (1868-1912) began with restoration of Emperor Mutsuhito to the throne in 1868. The new Emperor, who would reign until 1912, selected a new reign title — Meiji, or Enlightened Rule — to mark the beginning of a new era in Japanese history. The Meiji Restoration marks the birth of Japan as a modern nation, the abolition of the feudal system and restructured Japan along Western lines. The rallying cry for the nationalist was "Revere the Emperor, Repel the Barbarians."

The period began with a struggle for a supreme ideology. The historian Ian Buruma told the Japan Times: “There were many kinds of thinking that went into that. There were conservative nativists that believed in Shinto and the Emperor should be at the core of everything. But then there were also much more liberal thinkers...socialists and so on, who had a much more political idea of what it is to be Japanese... The blood-and-soil school...unfortunately, prevailed, and it is what ultimately led Japan into war.”

As was the case before, the Emperor was raised to a position of a living god but had little power but now power rested in the hands of reformers, the majority of them former students of Yoshida, and the landed oligarchy. The position of shogun was eliminated. Reformers and landowners fought for power.

In the meantime there were some natural disasters. On October 28, 1891, a devastating quake hit the former provinces of Mino and Owari. Records show that there tragedy caused 7,273 deaths and 17,175 casualties. Based on the destruction, the Mino-Owari Earthquake is estimated that the Richter Scale hit a magnitude of 8.0. [Source: Time.com, Japan's History of Massive Earthquakes]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com;

Meiji Empress in European clothes

EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com;JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com;PERRY, BLACK SHIPS AND JAPAN OPENS UP factsanddetails.com; MEIJI RESTORATION: REBELLIONS, YOSHIDA SHION, SAKAMOTO RYOMA AND THE MEIJI EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912) REFORMS, MODERNIZATION AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; MEIJI CONSTITUTION factsanddetails.com; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Meiji Period: Images of the Westernization of Japan MIT Visualizing Culture ; Wikipedia article on the Meiji Restoration Wikipedia ; Essay on Meiji Restoration aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; 1889 Constitution history.hanover.edu/texts Meiji Taisho http://www.meijitaisho.net Perry’s Visits Japan A Visual History brown.edu/japan/images ; Black Ships and Samurai MIT Visualizing Culture ; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ; Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912" Illustrated (2005) by Donald Keene Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “Meiji Restoration Losers: Memory and Tokugawa Supporters in Modern Japan (Harvard East Asian Monographs)” by Michael Wert Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 4: Early Modern Japan” by John Whitney Hall (Editor), James L. McClain Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan” by Christopher Benfey (Random House, 2003) Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “Breaking Open Japan: Commodore Perry, Lord Abe, and American Imperialism in 1853" by George Feifer Amazon.com; “Japan before Perry: A Short History” by Conrad Totman Amazon.com; “The First European Description of Japan, 1585" by Luis Frois Amazon.com;

Beginning of the Meiji Period

Part of the Charter Oath

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: By 1868, “a relatively small number of medium to low ranking samurai, the leaders coming from only four different domains in the southern part of Japan, had deposed the bakufu and established a new government in the name of the Emperor Meiji. This new government had many potential disadvantages. First, its leaders were young and lacking in prestige. Second, it had no money. Third, it had no army, the soldiers who had participated in the overthrow of the bakufu having been members of domain armies. On the other hand, however, there was a general consensus in Japan that change in the direction of a strong, centralized government was necessary to strengthen the country against imperialist aggression. Furthermore, the prestige of the emperor was high, and the young leaders of the restoration could use this prestige to their advantage, at least for a short while. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

The first official act of the Meiji Emperor was the Charter Oath of 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders to boost morale and win financial support for the new government proclaimed in the emperor’s name.. Although the promises were general and vague they set the course for the reforms made in the Meiji Period. The Charter Oath consisted of five promises to the people of Japan to bring about fundamental changes in the political system. These promises were: 1) establishment of deliberative assemblies, 2) involvement of all classes in carrying out state affairs, 3) freedom of social and occupational mobility, 4) replacement of "evil customs" with the "just laws of nature," and 5) an international search for knowledge to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule. [See Below]*

The Meiji government assured the foreign powers that it would abide by the old treaties negotiated by the Shogunate and announced that it would act in accordance with international law. To further dramatize the new order, the capital was relocated from Kyoto, where it had been situated since 794, to Tokyo (Eastern Capital), the new name for Edo. This move served to signify the location of the new government’s power (Tokyo) and its basis, the emperor’s authority. *

Charter Oath (of the Meiji Restoration), 1868

Part of the Charter Oath

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Charter Oath was a short but very important public document issued in April 1868, just months after the Meiji Restoration brought an end to the Tokugawa shogunate and installed a new Japanese government. Issued in the name of the Emperor Meiji (who was only 15 years old at the time), the text was written by a group of the young samurai, mainly from domains in southwestern Japan, who had led the overthrow of the Tokugawa and the “restoration” of imperial rule. The Charter Oath appeared at a time of considerable uncertainty in Japanese society, as people throughout the country were unsure of the intentions and priorities of the new regime governing Japan. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

The Charter Oath (of the Meiji Restoration), 1868 reads: “By this oath we set up as our aim the establishment of the national weal on a broad basis and the framing of a constitution and laws. 1) Deliberative assemblies shall be widely established and all matters decided by public discussion. 2) All classes, high and low, shall unite in vigorously carrying out the administration of affairs of state. “3) The common people, no less than the civil and military officials, shall each be allowed to pursue his own calling so that there may be no discontent. 4) Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of Nature. 5) Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.” [Source: “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Ryusaku Tsunoda, and Donald Keene, 1st ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), 137]

“Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the Shogunate and a move toward more democratic participation in government. To implement the Charter Oath, an eleven-article constitution was drawn up. Besides providing for a new Council of State, legislative bodies, and systems of ranks for nobles and officials, it limited office tenure to four years, allowed public balloting, provided for a new taxation system, and ordered new local administrative rules. [Source: Library of Congress *]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “This short document is a good example of Meiji-period political rhetoric. It is vague enough to allow most readers to see in it whatever they would like. It starts by reassuring everyone that government will be conducted reasonably, taking a wide variety of views into account (in fact, the Meiji state quickly moved to narrow the range of those who had a voice in policy making). It then urges everyone to pitch in and support the new government. The fourth item suggests that major changes might take place, but only by way of eliminating "evil" customs, and who could argue with that—or with the "just laws of Nature?" Finally, there is a recognition of the need to learn from the rest of the world, but with the proviso that such knowledge should ultimately serve to strengthen "imperial rule," that is, the power of the Meiji state.” ~

Meiji Government Consolidates Power

19th century daimyo Oota Sukeyoshi

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Even with the benefit of imperial prestige, the new government was in a precarious position. It moved quickly to consolidate its power. To do so successfully, it needed three things: money, power, and sex appeal. Power, in the case of the newly-created Meiji government, meant coercive police and military power. Indeed, coercive force is the very basis of any state or government, although the vast majority of governments go to great lengths to clothe such power in pleasant-looking attire. First, to buy time and forestall opposition, the new government appointed a wide variety of people to committees and advisory bodies that had impressive sounding names but little or no real power. Issuing the Charter Oath was part of this process. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“In terms of more substantive change, the government sought to eliminate the domains and build up its military power. Although these two moves were really two sides of the same coin, we examine them separately here. Eliminating the domains was a tricky process. Typically, each daimyo was willing to "give his domain back" to the emperor if he were well compensated and if the other major daimyo agreed to do the same. Securing such agreement required busy shuttle diplomacy. In the early spring of 1869, the four domains that led the Meiji Restoration—Satsuma, Choshu (the two most powerful), Tosa, and Hizen—issued a joint memorial "returning" their domains to the emperor and urging the other daimyo to do the same. Some did and were immediately re-appointed as governors of the same territory over which they had been daimyo. In substance, therefore, little had changed. In July of 1869, the new government ordered all daimyo who had not already done so to "return" their lands to the emperor. They, too, were appointed governors. The next year, the central government began to issue orders to these daimyo-turned-governors. Late in 1871, with the domains now theoretically at the emperor’s disposal, the Meiji government formally abolished them. In their stead it created prefectures (ken). Then, in 1872, it reduced the number of prefectures to 72, with later reductions bringing the number down to 43. By this time, most of the former daimyo no longer served as governors, although all of them were well compensated financially. The Meiji state was generous with the former daimyo because it did not want any of them to become rallying points for opposition.” ~

“In order to make these major changes, of course, the new state required coercive power in the form of police and soldiers, at least as a background presence. In 1869 and into 1870, the new government relied on soldiers on "loan" from the domain of Satsuma. During these years, debate took place within the government about how best to build an effective army. Some saw the samurai class as an ideal pool of soldiers, but most Meiji leaders argued that the samurai had long ago lost any special military skill they might have once had, and that samurai of different domains would not get along with each other. The majority of Meiji officials favored a conscript army both in the interests of creating the most effective army possible and in the interests of promoting national unity. In 1872, the new government announced a plan for military conscription, and it went into effect the next year. Awkwardly called a "blood tax," there was significant initial resistance to conscription among the common people. Nevertheless, the system worked, and by the late 1870s, the Meiji state had an effective army unconnected with the old domains or samurai class. Conscription continued until 1945, and it became an important means by which the state fostered a sense of "we Japanese" among ordinary people (more on this point later). ~

“The third item, sex appeal, is a metaphor for the state’s need for appealing, even seductive, symbols of authority and the nation. Ideal for this role was the Meiji emperor. His youth, good looks, and vigor (he had a vast appetite for food, drink, horseback riding, and sex) made him the perfect symbol of a new Japan, a nation both ancient yet modern. The Meiji state portrayed itself to the rest of Japan and to the world as being rooted in ancient Japanese cultural traditions, while at the same time leading Japan into the modern world.” ~

Opposition to the Meiji Government

19th century samurai

There was some resistance against the new Meiji government, According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: The 1870s were a time of numerous protests and uprisings of various sizes and scales. Ordinary people suffered under heavy tax burdens, conscription, and various intrusions of the state into realms of personal life such as dress and bathing customs. Many of the former samurai felt betrayed by the new government, and some were willing to rebel. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

The 1873 Korean crisis resulted in the resignation of military expedition proponents Saigo and Councillor of State Eto Shimpei (1834-74). Eto, the founder of various patriotic organizations, conspired with other discontented elements to start an armed insurrection against government troops in Saga, the capital of his native prefecture in Kyushu in 1874. Charged with suppressing the revolt, Okubo swiftly crushed Eto, who had appealed unsuccessfully to Saigo for help. Three years later, the last major armed uprising--but the most serious challenge to the Meiji government-- took shape in the Satsuma Rebellion, this time with Saigo playing an active role. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The most notable opposition to the Meiji Government was the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, which involved samurai and was the backdrop for the Tom Cruise film “The Last Samurai.” The revolt is also known as the Saigo Uprising, after one of its leaders Saigo Takamori. The revolt ended with the samurai being defeated at Tabarauzaka in Kumamoto and being stripped of their titles and power. Some committed seppuku.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: The greatest threat to the new government took place in 1877, when Saigo Takamori, hero of the Meiji Restoration and high government official in the early 1870s, led a revolt against the Meiji state. Saigo had become disgusted with the direction of the new state, especially with its moves to abolish the samurai class. Although he does not seem to have initiated the revolt, Saigo agreed to lead it once it began. He set out with an army of some 15,000 for samurai, but inadequate preparation and a terrible strategic blunder allowed the government to assemble sufficient forces to defeat Saigo’s army after seven months of hard fighting. Saigo committed suicide on the battlefield in the idealized tradition of the former samurai. His rebellion was the greatest threat to the new government but it also marked then end of large-scale, internal, military opposition. It was the last gasp of the old order, led, ironically, by someone who had sacrificed greatly to destroy that old order. By 1878, a decade after it had started, the new Meiji state had become firmly established. ~

The Saga Rebellion and other agrarian and samurai uprisings mounted in protest to the Meiji reforms had been easily put down by the army. Satsuma's former samurai were numerous, however, and they had a long tradition of opposition to central authority. Saigo, with some reluctance and only after more widespread dissatisfaction with the Meiji reforms, raised a rebellion in 1877. Both sides fought well, but the modern weaponry and better financing of the government forces ended the Satsuma Rebellion. Although he was defeated and committed suicide, Saigo was not branded a traitor and became a heroic figure in Japanese history. The suppression of the Satsuma Rebellion marked the end of serious threats to the Meiji regime but was sobering to the oligarchy. The fight drained the national treasury, led to serious inflation, and forced land values--and badly needed taxes--down. Most important, calls for reform were renewed. *

Important Figures from Meiji Period

Hirobumi Ito Hirobumi Ito (1841-1909) was an important leader in the early Meiji period. The "father" of the prewar constitution, he laid the foundations for the modern Japanese state by drafting the text of Meiji Constitution and forming the political bureaucracy." In 1885 he became Japan’s first prime minister.

Ito was greatly influenced by Austrian political theorist Lorenze von Stein, who stressed the importance of a balance of powers between nations and between the sovereign, executive and legislature. He said, “Modernization and the invention of tradition proceed together.” When he was young he was a member of a shogunal death squad that brutally assassinated samurai with their swords.

Saigo Takamorei, the leader of the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, was one of the most influential politicians of the Meiji period. Born into a low-ranking samurai family, he is regarded by some as the true Last Samurai and the lover of the fattest geisha in Kyoto (nicknamed Butahime, Princess Pig). After the the Satsuma Rebellion was put down he made a run for Shiroyama in Kagoshima prefecture. His forces grew weaker by the day. He died soon after that.

Another important hero of the period was Toshimichi Okubo, A samurai retainer in the Satsuma domain, he was instrumental in the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and was one of the main founders of the Meiji government and was the powerful politician in the Meiji administration until he was assassinated in 1878. Although he never assumed a government post, another influential Meiji period figure was Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901). He was a prolific writer on many subjects, the founder of schools and a newspaper, and, above all, an educator bent on impressing his fellow Japanese with the merits of Westernization.

Toshimichi Okubo

Toshimichi Okubo (1830-78), one of the most influential leaders of the Meiji Restoration, wrote, "A state of great disorder reigns over the country, as no genuine rule of law has been established yet and everyone is trying to usurp power...People demand whatever they please, but the government is at a loss to control them. As a result, it is yielding to them submissively."

Toshimichi Okubo

“Based on this situation, Okubo made up his mind to proceed with reforms,” Takashi Mikuriya, a professor of political science at the University of Tokyo, wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun. “To achieve the national goal of modernizing as quickly as possible, the country first had to establish a steadfast governing system. To that end, Okubo repeatedly advised the new regime — whose members kept behaving like a flock of sheep without shepherds — to impose an obligation of secrecy and define the chain of command, i.e., the line of authority and responsibility.” [Source: Takashi Mikuriya, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 1, 2011]

“In the same context, Okubo proposed that the governing system be established by distinguishing between "mass deliberation" and "public opinion," while giving due consideration to the adoption of "abnormal and irregular systems" or "normal and regular systems" as required. His proposal meant that the undisciplined regime should first shape "public opinion" — which would outline what the country should be in the future — out of irresponsible and vacillating rounds of "mass deliberation."

It also meant the government should implement "abnormal and irregular systems" that could bring about quicker results whenever necessary — without forgetting the importance of "normal and regular systems" as its higher ideal. Thanks to the Restoration government's "leap of death" as described by the late University of Tokyo Prof. Sato in his book "'Shi no Choyaku' wo Koete’seiyo no Shogeki to Nippon" ("Beyond the 'Leap of Death' — the Impact of the West and Japan"), the country became Asia's first modern nation state.

Foreign Influences During the Meiji Period

The Meiji oligarchy was aware of Western progress, and "learning missions" were sent abroad to absorb as much of it as possible. One such mission, led by Iwakura, Kido, and Okubo and containing forty-eight members in total, spent two years (1871-73) touring the United States and Europe, studying government institutions, courts, prison systems, schools, the import-export business, factories, shipyards, glass plants, mines, and other enterprises. [Source: Library of Congress]

Emperor Meiji dressed like a PrussianThe members of the delegation experienced culture shock in the United States and Britain and were unable to unravel the intricacies of American and British law and had trouble with other things like the button flies of the Western-style trousers the wore for the first time. Their visit to Germany, recently unified under Bismark, was more comforting. The Japanese saw Germany as a “new” country in a similar stage of development as their own country and were swayed by Bismark’s argument to build a strong military first and put their faith in that rather than “a naive faith in the law of nations.”

Upon returning, mission members called for domestic reforms that would help Japan catch up with the West. The revision of unequal treaties forced on Japan became a top priority. The returned envoys also sketched a new vision for a modernized Japan's leadership role in Asia, but they realized that this role required that Japan develop its national strength, cultivate nationalism among the population, and carefully craft policies toward potential enemies. No longer could Westerners be seen as "barbarians," for example. In time, Japan formed a corps of professional diplomats. [Source: Library of Congress]

Germany was the primary model. German language and literature were taught n elite schools not English or France, fascination with Germany also reached the masses. An 1887 magazine article read; “O blow thou German wind! Your approach is felt in scholarship, in the military, in student’s caps, in beer — though why you blow I don know.”

Development of Representative Government in Japan

The major institutional accomplishment after the Satsuma Rebellion was the start of the trend toward developing representative government. People who had been forced out or left out of the governing apparatus after the Meiji Restoration had witnessed or heard of the success of representative institutions in other countries of the world and applied greater pressure for a voice in government.[Source: Library of Congress]

A major proponent of representative government was Itagaki Taisuke (1837-1919), a powerful leader of Tosa forces who had resigned from his Council of State position over the Korean affair in 1873. Itagaki sought peaceful rather than rebellious means to gain a voice in government. He started a school and a movement aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy and a legislative assembly. Itagaki and others wrote the Tosa Memorial in 1874 criticizing the unbridled power of the oligarchy and calling for the immediate establishment of representative government. Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha (Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878. In 1881, in an action for which he is best known, Itagaki helped found the Jiyuto (Liberal Party), which favored French political doctrines. In 1882 Okuma established the Rikken Kaishinto (Constitutional Progressive Party), which called for a British-style constitutional democracy. In response, government bureaucrats, local government officials, and other conservatives established the Rikken Teiseito (Imperial Rule Party), a progovernment party, in 1882. Numerous political demonstrations followed, some of them violent, resulting in further government restrictions. The restrictions hindered the political parties and led to divisiveness within and among them. The Jiyuto, which had opposed the Kaishinto, was disbanded in 1884, and Okuma resigned as Kaishinto president. *

Government leaders, long preoccupied with violent threats to stability and the serious leadership split over the Korean affair, generally agreed that constitutional government should someday be established. Kido had favored a constitutional form of government since before 1874, and several proposals that provided for constitutional guarantees had been drafted. The oligarchy, however, while acknowledging the realities of political pressure, was determined to keep control. Thus, modest steps were taken. The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Council of Elders (Genronin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature. The emperor declared that "constitutional government shall be established in gradual stages" as he ordered the Council of Elders to draft a constitution. Three years later, the Conference of Prefectural Governors established elected prefectural assemblies. Although limited in their authority, these assemblies represented a move in the direction of representative government at the national level, and by 1880 assemblies also had been formed in villages and towns. In 1880 delegates from twenty-four prefectures held a national convention to establish the Kokkai Kisei Domei (League for Establishing a National Assembly). *

Although the government was not opposed to parliamentary rule, confronted with the drive for "people's rights," it continued to try to control the political situation. New laws in 1875 prohibited press criticism of the government or discussion of national laws. The Public Assembly Law (1880) severely limited public gatherings by disallowing attendance by civil servants and requiring police permission for all meetings. Within the ruling circle, however, and despite the conservative approach of the leadership, Okuma continued as a lone advocate of British-style government, a government with political parties and a cabinet organized by the majority party, answerable to the national assembly. He called for elections to be held by 1882 and for a national assembly to be convened by 1883; in doing so, he precipitated a political crisis that ended with an 1881 imperial rescript declaring the establishment of a national assembly in 1890 and dismissing Okuma. *

First Japanese House of Parliament

Ito Hirobumi and the Prussian Model of Government for Japan

Rejecting the British model, Iwakura and other conservatives borrowed heavily from the Prussian constitutional system. One of the Meiji oligarchy,Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909), a Choshu native long involved in government affairs, was charged with drafting Japan's constitution. He led a Constitutional Study Mission abroad in 1882, spending most of his time in Germany. He rejected the United States Constitution as "too liberal" and the British system as too unwieldy and having a parliament with too much control over the monarchy; the French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism. [Source: Library of Congress *]

On Ito’s return, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Five hundred persons from the old court nobility, former daimyo, and samurai who had provided valuable service to the emperor were organized in five ranks: prince, marquis, count, viscount, and baron. Ito was put in charge of the new Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems in 1884, and the Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Ito as prime minister. The positions of chancellor, minister of the left, and minister of the right, which had existed since the seventh century as advisory positions to the emperor, were all abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution and to advise the emperor. To further strengthen the authority of the state, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922), a Choshu native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional prime minister. The Supreme War Council developed a German-style general staff system with a chief of staff who had direct access to the emperor and who could operate independently of the army minister and civilian officials. *

When finally granted by the emperor as a sign of his sharing his authority and giving rights and liberties to his subjects, the 1889 Constitution of the Empire of Japan (the Meiji Constitution) provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who paid ¥15 in national taxes, about 1 percent of the population; the House of Peers, composed of nobility and imperial appointees; and a cabinet responsible to the emperor and independent of the legislature. The Diet could approve government legislation and initiate laws, make representations to the government, and submit petitions to the emperor. Nevertheless, in spite of these institutional changes, sovereignty still resided in the emperor on the basis of his divine ancestry. The new constitution specified a form of government that was still authoritarian in character, with the emperor holding the ultimate power and only minimal concessions made to popular rights and parliamentary mechanisms. Party participation was recognized as part of the political process. The Meiji Constitution was to last as the fundamental law until 1947. *

Meiji government

The first national election was held in 1890, and 300 members were elected to the House of Representatives. The Jiyuto and Kaishinto parties had been revived in anticipation of the election and together won more than half of the seats. The House of Representatives soon became the arena for disputes between the politicians and the government bureaucracy over large issues, such as the budget, the ambiguity of the constitution on the Diet's authority, and the desire of the Diet to interpret the "will of the emperor" versus the oligarchy's position that the cabinet and administration should "transcend" all conflicting political forces. The main leverage the Diet had was in its approval or disapproval of the budget, and it successfully wielded its authority henceforth. *

In the early years of constitutional government, the strengths and weaknesses of the Meiji Constitution were revealed. A small clique of Satsuma and Choshu elite continued to rule Japan, becoming institutionalized as an extraconstitutional body of genro (elder statesmen). Collectively, the genro made decisions reserved for the emperor, and the genro, not the emperor, controlled the government politically. Throughout the period, however, political problems were usually solved through compromise, and political parties gradually increased their power over the government and held an ever larger role in the political process as a result. Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as prime minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genro who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives. Although not fully realized, the trend toward party politics was well established. *

Meiji Constitution

A new constitution adopted in 1889 created a constitutional monarchy and formally ended feudalism, dismantled the old bureaucratic institutions, outlawed samurai and guaranteed individual rights. A Western-style Parliamentary government and legal code were introduced. Many elements were inspired by Germany, under the unifying, authoritarian leader Otto Bismark.

The process of creating a new constitution began in the early 1870s with the visit by a Japanese delegation to the United States, Britain and Germany. Buruma wrote that “Japanese democracy, as defined by the Meiji Constitution, was a sickly child from the beginning. The spirit of the Constitution was a mixture of German and traditional Japanese authoritarianism. But the greatest danger, in the long run, lay in its vagueness. For the emperor was expected to stand above the worldly affairs, while a bureaucratic elite made political decisions in his name. At the same time, Japan’s armed services vowed their loyalty only to the monarch and not the civilian government.” The constitution made it possible for people to do all kinds of things in the Emperor’s name. And these things overrode the weak democracy.

Ceremony for the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Promulgated on February 11, 1889, the Meiji Constitution was a major landmark in the making of the modern Japanese state and in Japan’s drive to become one of the world’s advanced, “civilized” powers. Drafted by Itō Hirobumi, a group of other government leaders, and several Western legal scholars, the document was bestowed on the Japanese people by the Emperor Meiji and established Japan as a constitutional monarchy with a parliament (called the Diet), the lower house of which was elected. Itō and his associates drew heavily on Western models, and especially the conservative traditions of Prussia, in creating a constitution that reserved almost unrestricted power for the Emperor while still permitting the creation of democratic institutions. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Book: "The Meiji Constitution: The Japanese Experience of the West and the Shaping of the Modern State" by Takii Kazuhiro (International House of Japan, 2007)

See Separate Article on THE MEIJI CONSTITUTION

Changes in the Role of the Emperor

The myth of the Japanese Imperial Family's divine origin has been part of Japanese folklore for a long time. Even so, the Emperor’s divine status before World War II was not so much the result of some ancient belief but rather a manifestation of late 19th century politics. Inspired somewhat by European Christianity and European monarchies, reformers in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) revived the pontifical role of the Emperor when it made Shinto the state religion as a way of unifying Japan. The reformers then went a step further and made the Emperor commander and chief of the military and the preeminent leader of Japan's political structure. Military leaders were directly responsible to the emperor, who also had the power to appoint and reject generals, admirals and prime ministers.

By the 1930s the authority of the Emperor was unquestioned. Every student in every Japanese school bowed before the Emperor’s photograph every morning and teachers described how the first emperor descended from the gods as if it were historical fact.

The Emperor and other royals were not allowed to touch money or be photographed or even looked at by ordinary people. Criticism of the emperor was unheard of. Any one that ventured to say anything bad about him risked a long prison term or even death.

The Japanese constitution of 1889 declared the emperor sits upon "the throne of a lineal succession unbroken through the ages eternal" and pre-World War II Japanese student were taught that the emperor was a god. Shinto doctrines were taught in school; Shinto shrines were supported by the government; and religion and nationalism developed strong links.

State Shintoism

Emperor Meiji dressed like a Shinto priest

After Meiji Restoration in 1868, and especially during World War II, Shinto was promoted by the authorities as a state religion (almost the same way that Islam is the state religion in Saudi Arabia).

Inasmuch as the Meiji Restoration had sought to return the emperor to a preeminent position, efforts were made to establish a Shinto-oriented state much like the state of 1,000 years earlier. An Office of Shinto Worship was established, ranking even above the Council of State in importance. The kokutai ideas of the Mito school were embraced, and the divine ancestry of the imperial house was emphasized. The government supported Shinto teachers, a small but important move. Although the Office of Shinto Worship was demoted in 1872, by 1877 the Home Ministry controlled all Shinto shrines and certain Shinto sects were given state recognition. Shinto was at last released from Buddhist administration and its properties restored. Although Buddhism suffered from state sponsorship of Shinto, it had its own resurgence. Christianity was also legalized, and Confucianism remained an important ethical doctrine. Increasingly, however, Japanese thinkers identified with Western ideology and methods. [Library of Congress]

The historian Ian Buruma told the Japan Times: “State Shinto was deliberately set up in the 19th century as a Japanese version of the Christian church.” The Japanese “were always looking for reasons to explain why the West was so powerful and Japanese thinkers in the 18th century came to conclusion that it all came down to Christianity: It was the church that tied people together and made them obedient to their leaders. So they concluded that what they needed was a national church, and that became State Shinto.”

Over time Shintoism was co-opted from it decentralized animists roots into a state-sponsored war religion. Ian Buruma has suggested that State Shinto was created by “grafting German dogma on Japanese myths. They shared military discipline, mystical monarchism and blood-and-soil propaganda about national essences.”

Death of the Meiji Emperor

Maresuke Nogi

The Emperor Meiji died in 1912. His funeral cannonades were so grand that the great Japanese novelist Soseki Natsume was moved to call it the end of an era. At his funeral one the emperor's leading generals and his wife committed suicide in accordance with samurai ritual of "following one's lord to death."

General Maresuke Nogi marked the death of Emperor Meiji by committing ritual suicide (seppaku) — by thrusting a knife into his stomach, twisting it and making a slash across the stomach — with his wife in 1912. His wife, apparently willingly, plunged a dagger into her heart.

In 1877 Nogi had asked the Emperor for permission to commit seppaku following his regiment’s defeat in the Satsuma Rebellion and the loss of the Emperor’s banner to the enemy. He was crushed when his request was turned down, expressing his feelings a poem that went: “My self is nothing but a person scared of death.” He made the request for seppaku again in 1905 after losing two sons in the war and again was turned down. The state propaganda machine seized up his successful suicide as the ultimate act of self-sacrifice for the emperor and was used for propaganda purposes to aid the rise of the military. A number of writers wrote about the event.

Meiji Period Imperial Rulers (1868–1912) and After

Meiji (1868-1912).

Taisho (1912–1926).

Showa (1926–1989).

Heisei 1989–present).

Kinjo (1989–present).

[Source: Yoshinori Munemura, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated January 2024