EUROPEAN HAMSTERS

European hamsters (Cricetus cricetus) are also called black-bellied hamsters and common hamsters. They only species of hamster in the genus Cricetus, they are native to grasslands and similar habitats in a large swath of Eurasia. In the past, they were considered agricultural pests and were trapped for its fur. Their population has declined dramatically in recent years and they are now considered critically endangered. The main threats to the species are thought to be intensive agriculture (namely corn), habitat destruction, and persecution by farmers. [Source: Wikipedia]

European hamsters (European hamsters) can be found as far west as northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands and as far east as the Altai Mountains and Yenisey River in Russia. They In Europe they range as far north as Germany and Belarus and as far south as Bulgaria and Ukraine. In the east they can be found in China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan. The preferred natural habitat of European hamsters is steppe and grassland, but they have expanded into agricultural areas and some green patches in urban areas. Their burrows are typically extensive and occur in dense loess or clay soils. They are generally found at an average elevation of 400 meters (1312 feet). [Source: Sierra Lippert, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

European hamsters range in weight from It weighs 220 to 460 grams (7.8–16.2 oz) and They have a head and body length that ranges from to 20 to 35 centimeters (8–14 inches, including a four-to-six centimeter (1.6–2.4 inch) tail. Their average basal metabolic rate is 1.251 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males have an average mass of 450 grams (one pound) while females average 359 grams (12.6 ounces). Adult males have an average length of 24.1 centimeters (9.5 inches) while females average approximately 23.7 centimeters (9.3 inches).

European hamsters have stocky bodies covered by reddish-brown to greyish-brown fur on their back and sides. Their snouts, lips, throats, cheeks and feet are white and their ventral surface is black, which is why they are sometimes called black-bellied hamsters. The hairs on their short tails are shorter than those on the rest of their bodies. European hamsters have prominent, dark eyes and broad, oblique nostrils that run caudally. Their facial whiskers are straight and stiff and occur in up to 30 brown or white hairs on each side. The soles of their forefeet have five pads, while their hindfeet are much longer and have six pads. Their ears are dorsomedially directed and average at a length of 2.3 to 3.2 centimeters. Their dentition consists of incisors and molars only, with a dental formula of 1/1, 0/0, 0/0, 3/3. European hamsters have unusually long lifespan for rodent, living up to eight years.

European hamsters are categorized as granivores (eat seeds and grain), herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). They eat primarily ear grasses, seeds and grains but also eat roots, fruits, and legumes, and occasionally and opportunistically eat insects and insect larvae. They store and cache food. Predators of European hamsters in the wild include Red foxes, stoats, least weasels, European badgers as well as feral and domesticated cats and dogs. Among the birds of prey and other birds that take them are red kites, common kestrels, common buzzards, lesser spotted eagles, Western marsh harriers, Montagu’s harriers, hen harriers, hooded crows, common ravens, rooks, grey herons and white storks. For defense, European hamsters stay in or close to their burrows for quick escapes and have camouflage coloring

RELATED ARTICLES:

HAMSTERS: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

GOLDEN (SYRIAN) HAMSTERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, DISCOVERY, DOMESTICATION africame.factsanddetails.com

MOUSE-LIKE HAMSTERS: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR, AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

GERBIL SPECIES IN ASIA: MONGOLIAN, GREAT, INDIAN factsanddetails.com

GERBILS OF THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA africame.factsanddetails.com

JIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND REPRODUCTION africame.factsanddetails.com

JERBOAS OF CENTRAL ASIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

JERBOAS OF THE MIDEAST AND NORTH AFRICA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES africame.factsanddetails.com

EGYPTIAN JERBOAS: GREATER, LESSER, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR africame.factsanddetails.com

PYGMY JERBOAS (WORLD'S SMALLEST RODENTS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

European Hamsters Behavior and Reproduction

European hamsters are generally solitary, nocturnal (active at night), cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), hibernate (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements), solitary territorial (defend an area within the home range). Males on average occupy a larger territory (1.85 hectares) than females (0.22 hectares). [Source: Sierra Lippert, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The behavior of European hamsters depends of the seasons. In late summer they start building up body fat reserves and their fur darkens for hibernation, which occurs from mid-October to mid-March. They hibernate in a curled position with outstretched forelegs and wake up every five to seven days to feed. During hibernation they can be found in their burrows as far as two meters below ground; they are generally only 30 to 60 centimeters deep in summer. European hamsters create extremely extensive tunnels of with separate chambers for dwelling, food storage, and urination. Their tunnels typically have a diameter of eight to nine centimeters with several exits. They are perceived to be highly adaptive, due to their dietary opportunism and ability to burrow in urban settings. They use their cheek pouches to transport food back to their burrows. They are very aggressive towards members of their own species except during breeding season.

European hamsters sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks produced by special glands on their flanks and placed so others can smell and taste them. During breeding season, females run in figure eights while males make mating calls with increasing volume before mating. Aggressive behavior include grunting, spitting and mobbing. When fighting, European hamsters stand on their hind legs, wrestle, jump and bite.

European hamsters are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners, and females can mate again shortly after giving birth to their first litter,. The breeding season often begins in March to May and extends as long as August. Females can have up to three litters in one breeding season, with the first arriving in mid-May. To attract a mate, females run in figure eights. Interested males run close behind and produce mating calls with increasing volume. Copulation occurs multiple times before mating is finished. The gestation period ranges from 18 to 21 days. The number of offspring ranges from three to 7, with the average number of offspring being seven. Young are born with their eyes closed and are altricial — relatively underdeveloped — but they developed very quickly. Parental care is provided by females, who can be extremely territorial when with young and can be pregnant while providing milk for their pervious litter. The age in which young are weaned ranges from 21 to 28 days. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 80 to 90 days, with the average being 60 days. On average males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 56 days.

European Hamsters, Humans and Sharp Population Declines

In 2020, European hamsters were classified as critically endangered across their range on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. Not so long before that they were are listed as a species of Least Concern. The reasons for their sharp declines are not fully understood but are believed to be linked to habitat loss due to intensive agricultural practices, and the building of roads that fragment populations, and to climate change, Historical fur trapping and the use of hamsters in research, pollution and light pollution have also been suggested as reasons for the reducution of local populations.

Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In the past, ‘hamsters ate the crops around their burrows and sometimes destroyed swaths of farmland during population explosions, when as many as 2,000 crowded into a single hectare. Farmers killed hamsters to protect their crops and sell their fur, which was fashionable throughout Eastern Europe. (About a hundred hamsters are killed to make every hamster-fur coat.) In 1966, trappers in Saxony-Anhalt in East Germany killed more than a million hamsters in a single season. [Source: Ben Crair, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

“Scientists expected the hamster to bounce back after most Western European countries banned trapping in the 1980s and ’90s. A female typically produced three litters of six to 12 pups every summer, which meant hamsters should have quickly repopulated the fields. But their numbers continued to plummet. In 2001, there were just 1,167 hamster burrows in Alsace. By 2012, there were 206.

“Not since the passenger pigeon, perhaps, had an abundant animal disappeared as quickly as the hamsters. Intensive agriculture was making the countryside increasingly inhospitable for wildlife. Something was causing widespread decline in the hamsters: field biologists counted fewer and fewer hamsters emerging from their hibernation burrows every year. The species cannot survive without reproducing quickly, since most hamsters only live a year or two before falling prey to a fox, polecat or raptor. “It’s like the job of a hamster is to be eaten,” says Peer Cyriacks, an environmental biologist with the German Wildlife Foundation.

“The hamster population in Alsace dropped sharply during the same decades in which corn came to dominate the region. These days, corn covers between half and 80 percent of Alsace’s farmland in a given year. By 2015, an Alsatian hamster had, on average, fewer than one litter per season with just one to four pups. Mathilde Tissier, a doctoral candidate in biology at the University of Strasbourg, suspected that the reproductive failure had something to do with the lack of variety in the hamster’s diet. The typical cornfield is at least five acres, while a common hamster’s home range is less than a tenth of that size. Most hamsters in a cornfield will never encounter another plant species.

European Hamsters Cannibalism Linked to Corn-Eating?

Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“Tissier began her experiment in 2014. She fed the lab hamsters every morning with either corn or wheat, the two main crops in Alsace, as well as an afternoon supplement of earthworm or clover. She predicted the hamsters on the corn-earthworm diet would give birth to the largest litters and heaviest pups. Instead, she was shocked when the first of these hamsters ate her litter. Her dismay turned to panic when, over the next two weeks, every single hamster in the corn-earthworm group cannibalized her newborns. [Source: Ben Crair, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

“Tissier wondered if it was a lack of maternal experience: Young rodent females sometimes kill their first litter. So she bred all the worm- and cornfed hamsters a second time. “Every time I left in the evening, I hoped that this time the litter would still be there in the morning,” Tissier says. But every hamster except for one cannibalized her second litter, and one of the surviving pups ate its siblings as soon as their mother weaned them.

“One by one, Tissier eliminated possible causes. The corn-earthworm combo was not deficient in energy, protein or minerals, and the corn did not contain dangerous levels of chemical insecticide. Tissier was running out of ideas when an organic corn farmer suggested she look into human diets and amino acids. The more research papers Tissier read, the more she realized she had not made an error in her experiment. The thing making her hamsters hungry for their own infants was the corn itself.

“So she designed a new experiment, where they fed the hamsters corn, earthworms and a vitamin B3 supplement. When the first hamster in the group cannibalized its litter, Tissier worried that pellagra was another false lead. But every subsequent hamster that gave birth weaned her pups, and the first hamster successfully weaned a second litter. Tissier had solved the mystery and corrected the cannibalism.

Campbell's Dwarf Hamsters

Campbell's dwarf hamsters (Phodopus campbelli) are native to China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia. Also known as Campbell's hamsters, they were given their common name by Oldfield Thomas in honor of Charles William Campbell, who collected the first specimen in Mongolia in 1902. They are distinguished from the closely related Djungarian hamsters by their smaller ears and lack of dark fur on their crown. Campbell's dwarf hamsters also typically have a narrow stripe on their backs that Djungarian hamster’s don’t have and have brown or gray fur on their stomach. Campbell's dwarf hamsters are fairly common in the wild and are raised in captivity and kept as pets. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. [Source: Wikipedia]

Campbell's dwarf hamsters are found in relatively large numbers on the Altai Mountains in Mongolia and Kazakhstan; Transbaikalia and Tuvinskaya (Tuva) Autonomous Region in Russia; and Inner Mongolia, Heilungkiang and Hebei in China. They inhabit burrows with four to six horizontal and vertical tunnels in steppes and semi deserts. The burrow of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters have both horizontal and vertical tunnels. The burrows can be more than one meter deep and have an an average depth of about a third of a meters (one foot). A nest is often constructed at the end of a tunnel and comprised of dry and insulating materials including grasses, feathers and wool. Seeds and nuts are typically cached close to the nesting area. In the Barga and Great Kingan regions of Manchuria, Campbell’s dwarf hamsters have been observed sharing tunnels and burrows with several species of pikas. On the Mongolian Plateau they do not dig their own burrows; instead they share the burrows of several species of jirds or gerbils. Known natural predators of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters include corsac foxes, eagle owls, steppe eagles, common kestrels and saker falcons [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters, Roborovskii dwarfs and white winter dwarf hamsters were collectively introduced to the American pet industry as “dwarf hamsters” in the mid-1990s. Their small size, mild temperament and inexpensive maintenance made them popular with first-time pet owners and was viewed by parents as a particularly ideal pet for young children. Another plus Campbell’s dwarf hamsters, compared with larger hamsters, is that they got along well with each other in a group. The same characteristics that made Campbell’s dwarf hamsters as attractive pet also made them ideal as research animals — and they have been used in numerous cytogenetic and cancer studies.

Campbell's Dwarf Hamster Characteristics, Diet

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are very small in size. Their average weight is 23.4 grams (0.82 ounces) and they range in length from 8 to 10.3 centimeters (3.15 to 4.06 inches), with their average length being 10.2 centimeters (4.02 inches). Their average head and body length of 8 centimeters (3.1 inche); an average hind foot is of 13.5 millimeter (0.53 inch) long; and their tail length is five millimeters. (0.20 inches). The basal metabolic rate of these animals ranges from 1.63 +/- 0.38 to 1.88 +/- 0.57 cubic centimeters of oxygen per gram per hour. Their lifespan in captivity is typically two to 2.5 years. Sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The fur of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters is short and silky. Their undersides are covered in soft, buff, light grey fur while their back and head, are woody brown in color. The underfur is quite short and is a dark slate grey. A defined charcoal stripe runs from between the ears to the tail. The pads of all digits, and the small tail, are covered in silky white fur. Like other hamsters, Campbell’s dwarf hamsters possess large internal cheek pouches that terminate above the scapula and are used to temporarily store food.

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are often confused with winter white dwarf hamsters. The ears of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are generally smaller than those of winter white dwarf hamsters and the mid-dorsal stripe of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters is both thin and defined and the area where the dorsal fur meets the ventral fur is a creamy light yellow. Moreover, the underfur of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are dark grey, whereas that of winter white dwarf hamsters is white.

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) but are also categorized as folivores (eat leaves), granivores (eats seeds and grain) and even omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Their diet consists mainly of a wide variety of seeds, nuts and vegetation, including Stipa capillata, Iris ruthenia and Iris flavisima, as well as wood, bark, stems, fruit and flowers Animal foods include occasional insects terrestrial non-insect arthropods and mollusks. In the wild, Campbell’s dwarf hamsters store and cache food. Pets Campbell’s dwarf hamsters eat almost any commercially prepared hamster food, usually made with corn, oats, sunflower, peanuts, dried fruits, dehydrated vegetables, alfalfa and minerals or salts. /=\

Campbell's Dwarf Hamster Behavior and Reproduction

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), and territorial (defend an area within the home range). A 1992 survey of the home ranges of several female Campbell’s dwarf hamsters in the Lake Tere Xol region of Mongolia found their average territory size was 3.5 square kilometers. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are generally classified as solitary species but in captivity the have a high tolerance for other members of their species in a shared territory. Captives ones also more active in the day than their wild counterparts. Campbell’s dwarf hamsters scuttle when moving quickly. In order to avoid predators they often move both abruptly and quickly. The maximum documented running speed of these hamsters is 6.5 km/hr (4 mph).

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with chemicals: they leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Both males and females utilize urine and feces to identify territory. Secretions from their ventral sebaceous glands and Harderian glands, located behind the animal’s ears, are utilized not only for territory identification, but also for communication. The oral sebaceous glands of Campbell’s dwarf hamsters also serve to mark all of the contents that enter or leave the animal’s cheek pouches.

Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners and employ sperm-storing (producing young from sperm that has been stored, allowing it be used for fertilization at some time after mating). Females have an estrous cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females. Wild Campbell’s dwarf hamsters breed three to five times per year, whereas captive ones breed year-round. The breeding season varies by geographic location. Breeding begins in April and May in the Tuva and Transbaikalia regions of Mongolia, respectively, and ends in late September or early October. The gestation period ranges from 13.5 to 22 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to 12, with the average number of offspring being 8.2.

Young are altricial. This means that young are born relatively underdeveloped and are unable to feed or care for themselves or move independently for a period of time after birth. At birth, Campbell’s dwarf hamsters are completely helpless and hairless. Incisors and small claws are present, but the ears and eyes are both sealed. Pre-weaning and Pre-independence protection is provided by males and females. The average weaning age is 17 days, with independence occurring on average at 23 days. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 48 days and males do so at 23 days.

Roborovski Hamsters

Roborovski hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii) are the world’s smallest hamsters. Also known as desert hamsters, Robo dwarf hamsters, Roborovski’s dwarf hamsters and simply dwarf hamsters, they belong to the dwarf hamster genus (Phodopus), are only five centimeters (2.0 inches) in length and weigh only 20 grams (0.71 oz) Distinguishing characteristics other than their small size include eyebrow-like white spots and a lack of a dorsal stripe like that found on the other members of the genus Phodopus. Roborovski hamsters are known for their speed and endurance and have been said to run up to 10 kilometers (6 miles) a night. Their common name and scientific name comes from Russian explorer Vladimir Ivanovich Roborovski (1856 – 1910), who collected the holotype of this species. The average lifespan of Roborovski hamsters is two to four years. [Source: Wikipedia]

Roborovski hamsters are found in Central Asia at elevations from 878 to 1,450 meters (2,880 to 4,757 feet). They are most numerous in south, central and northwestern Mongolia. Their northern range extends from the Hunshandake sandy land and the Mongolian Gobi deserts to adjacent territories of northern China. They are present but less numerous in the Ordos desert of China, south of the Zaisanskaya Depression, in east Kazakhstan and in the southern portions of the Tuva Republic in Russia. [Source: Allison Kolynchuk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Roborovski hamsters favor habitats with loose soil that facilitates burrow digging. The sandy soils of semi-deserts, steppes and grasslands offer the preferred terrestrial substrate over clay soils. Sparse, shrubby vegetation in these habitats also aids in burrow construction. In Mongolia, vegetation surrounding hamster burrows typically extends to a height of 75 centimeters. Dominant herbaceous or gramineous plants species are caragana (Caragana tibetica), fabales (Ammopiptanthus mongolicus), Cynanchum (Cynanchum komarovii), and Zygophyllum pterocarpum. Agricultural landscapes that are grazed over by stocks of sheeps and goats, grain fields and orchards are also habitat for Roborovski hamsters. Access to water is not so important to these hamsters. They are found in areas of low water availability, such as seasonal floodplains or mountain valleys.

The semiarid regions where Roborovski hamsters thrive are subjected to a continental type of climate with high variation in seasonal and daily temperatures. In the Alashan desert of Mongolia, mean annual precipitation is low (ranges from 45 to 215 millimeters per year). Mean annual temperature is moderate (8.3°C), but extremes are reached in January (lows of -35°C) and July (highs of 40°C). There is also variation between the highest daytime and lowest night temperatures; temperature within 24 hours can vary by 15°C or 20°C, due to the low buffering capacity of sparse vegetation.

Roborovski Hamster Characteristics and Diet

As we said earlier Roborovski hamsters are the smallest of all hamster species They range in weight from 17.5 to 27.2 grams (0.62 to 0.96 ounces) and range in length from seven to to 10.6 centimeters (2.76 to 4.17 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 2.61 cubic centimeters of oxygen per gram per hour. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males and females have different shapes. [Source: Allison Kolynchuk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Allison Kolynchuk wrote in Animal Diversity Web: In accordance with their small body size, the skull is delicate with a long and slender rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth). The braincase is broad in front, while rounded dorsally. Their auditory bullae are reduced and flattened. These hamsters possess a pair of upper and lower arc-shaped, ever-growing, groove-less incisors. The sharpness of the incisors is maintained through resistance to wear on the hard, enamelled, buccal tooth edge. The feet consist of short and broad bones internally, while they are densely furred externally to protect against the heat of the sandy soils. As with all rodents Roborovski hamsters are gnawing animals. Internal cheek pouches are used to store and transport food to caches. Cheek pouches are an extension of the oral cavity and, when full, extend past the shoulders. Roborovski hamsters possess both a forestomach and a glandular stomach. The small intestine makes up 60 percent, the large intestine 27 percent and the caecum 13 percent of the total length of the intestine. The species has a diploid karyotype of 2n = 34 chromosomes, which is higher than that of striped desert hamsters (Phodopus sungorus). /=\

Their fur is soft and thin and reaches a maximum length of approximately 9 millimeters. Roborovski hamsters are cryptic, matching with the environmental sand, with a light-brown colored fur and lack of a mid-dorsal stripe. Prominent white patches are above each eye and at the base of each ear pinna. The mouth area, entire ventral surface, limbs and both sides of every foot are also completely covered with thick white fur. The external parts of the ear are grayish-brown anteriorly, with the posterior half and inside being white. There are no seasonal changes in the coloration, volume or density of the fur. Domestication has resulted in altered fur characteristics when compared to the wild state. Colored domestic variants include pure white hamsters and those with a white head that contrasts a brown torso. /=\

Roborovski hamsters are primarily granivores (eat seeds and grain) but are also recognized as herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). They mainly consume plant seeds (70 to 90 percent of their diet), as well as plant leaves and plant stems. Succulent, green plant tissue is typically absent from their diet. In the Russian republic of Tuva, they feed primarily on the seeds of Alyssum desertorum, Caragana spp., Nitraria spp., Dracocephalum peregrinum, grams,Astragalus spp., and Carex spp. Coprophagy of their own or another individual's dung may be done for increased nutrient intake. Water intake is partially provided by the insects — beetles, earwigs and locusts — that make up a small portion of their diet. Food intake increases during the winter months to coincide with the increased need for thermogenesis. The hamsters adapt to temperature and food availability fluctuations by increasing their ability to digest food. They are able to convert food into metabolized energy at around 80 percent efficiency, but can increase up to 97 percent during prolonged cold exposure. This is higher than that of other other rodent species. Two to four food caches are stored in underground burrows. /=\ .Roborovski hamsters are resistant to dehydration in their arid environments. They are well-adapted to low water availability though the morphological and functional adaptations of their kidney.

Roborovski Hamster Behavior and Reproduction

Roborovski hamsters are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area). Due to their small size and relatively slow movement, these hamsters have small home ranges. [Source: Allison Kolynchuk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Roborovski hamsters are generally solitary, but may be found living in pairs while not rearing young. They are shy and meetings usually result in one hamster running to hide when the other approaches. Sociopositive behaviour towards each other includes investigative sniffing, sitting in contact and allogrooming. They are more passive when compared with closely related hamster species and will freeze when presented with a stressful stimulus. When Hunting and foraging the hamsters proceed to the edge of their home range then systematically search for seeds or prey. When compared to the closely-related striped desert hamster, Roborovski hamsters generally have increased locomotor activity in both natural and captive settings.

Roborovski hamsters dig burrows into the sides of sand dunes. They have one or two entrance holes (4 centimeters diameter). They extend deep into the soil (90 centimeters deep), where they contain one nest and two to three food caches. Entrance holes are quickly hidden by loose sand. Nesting material may or may not be present. Burrows are likely similar to those of the closely-related golden hamster, such that entrances lead into a 18 centimeters to 45 centimeters long vertical tunnel, or "gravity pipe", that falls into a horizontal nest chamber and usually no more than a single adult occupies a burrow. Nest chambers are up to 20 centimeters wide and contain a spherical nest made opportunistically out of dry material found in the environment. Urination is restrained to a 10 centimeters to 15 centimeters dead-end tunnel, while defecation occurs throughout the entire underground structure. Food storage occurs in multiple tunnels that measure between 100 and 150 centimeters that run at varying angles from the nest chamber. /=\

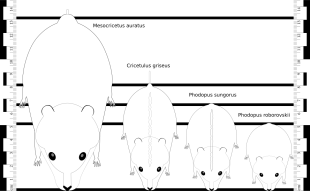

golden or Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus), most common pets

Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus).

winter white dwarf hamster (Phodopus sungorus)

Roborovski hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii)

There is no sign of torpor or hibernation by Roborovski hamsters during the winter months, even during extremely low temperatures. Activity does decrease in the winter months: in February and March when Roborovski hamsters are active in their burrows for less than ten minutes a day. These hamsters do not store fat in preparation for winter. They do, however, have gradual weight gain over the summer months (from approximately 13 grams in spring to approximately 19 grams in autumn) as weight loss from the previous winter is re-gained.

Roborovski hamsters are monogamous and employ sexual induced ovulation (release of a mature egg from the ovary). Females have an estrous cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females and can breed up to four times yearly with the main breeding season running from February to October. Courtship behavior begins when females display increased sexual activity during estrus. Mating activities begin as mates approach from a distance, then progresses to olfactory investigation of the anogenital region and contact thereof, circling and lordosis. Mating cumulates with the mounting of mates and then terminates with copulation. The gestation period ranges from 20 to 22 days. The number of offspring ranges from three to 10, with the average number of offspring being 3.75.

Young are altricial. meaning that they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided mostly by females but males help some by remaining in the same burrow network as his family group and adding material to the food storage tunnels. . The age in which young are weaned ranges from 18 to 30 days and the age in which they become can be as low as 20 days.. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two months, and males do so at two to five months.

Roborovski Hamsters, Humans and Predators

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as a species of Least Concern. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Based on mitochondrial DNA haplotypes, domestic Roborovski hamsters are traced back to descendants in the Zaisan basin of Kazakhstan. They were initially domesticated in the Moscow Zoo. Subsequent spreading to other countries began soon after their introduction to the Zoological Society of London in the late 1970s. Although present in captivity since the 1970s, Roborovski hamsters are not easily maintained or bred in captivity when compared to other hamsters. They are difficult to acclimate and display heightened levels of hyperactivity in laboratory settings. Therefore, their use in laboratory research is limited and they are far less studied in comparison to other dwarf hamsters. [Source: Allison Kolynchuk, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Roborovski hamsters are the most common species preyed-upon by long-eared owls. They make up 18 percent of the long-eared owl diet in their northwestern Chinese range. Other natural predators include foxes, weasels, snakes, and other owls. Although hawks and falcons (Order Falconiformes) may prey upon Roborovski hamsters, they do not constitute a large threat due to the nocturnal (active at night), activity of these hamsters. /=\

Anti-predator adaptations include morphological crypsis and behavioural modifications. The dorsal fur of Roborovski hamsters is of a light brown color that is camouflaged well with the underlying sand from arial vantage points. Although risk of predation is increased through their habit of prolonging foraging activity during highly illuminated nights, anti-predator strategies (including increased sensory vigilance and freezing) are also increased on such nights. The preferred hiding places for these hamsters upon encountering a predator are under shrubby vegetation

Hamster, vole and lemming species: 1) Roborovski’s Desert Hamster (Phodopus roborouskii), 2) Campbell's Desert Hamster (Phodopus campbelli), 3) Striped Desert Hamster (Phodopus sungorus), 4) Golden Hamster (Mesocricetus auratus), 5) Ciscaucasian Hamster (Mesocricetus radder), 6) Brandt's Hamster (Mesocricetus brandii), 7) Romanian Hamster (Mesocricetus newtoni), 8) Gray Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus migratorius), 9) Long-tailed Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus longicaudatus), 10) Striped Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus barabensis), 11) Sokolov’s Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus sokolouvi), 12) Ladakh Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus alticola), 13) Tibetan Dwarf Hamster (Cricetulus kamensis), 14) Gansu Hamster (Cansumys canus), 15) Greater Long-tailed Hamster (Tscherskia triton), 16) Mongolian Hamster (Allocricetulus curtatus), 17) Eversmann’s Hamster (Allocricetulus eversmanni), 18) Common Hamster (Cricetus cricetus), 19) Long-clawed Mole Vole (Prometheomys schaposchnikowi), 20) Round-tailed Muskrat (Neofiber alleni), 21) Common Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), 22) Western Heather Vole (Phenacomys intermedius), 23) Eastern Heather Vole (Phenacomys ungava), 24) White-footed Vole (Arborimus albipes), 25) Red Tree Vole (Arborvmus longicaudus), 26) Sonoma Tree Vole (Arborimus pomo), 27) Northern Bog Lemming (Synaptomys borealis), 28) Southern Bog Lemming (Synaptomys cooperi), 29) Wood Lemming (Myopus schisticolor), 30) Amur Brown Lemming (Lemmus amurensis), 31) Norway Brown Lemming (Lemmus lemmus), 32) Siberian Brown Lemming (Lemmus sibiricus), 33) Nearctic Brown Lemming (Lemmus trimucronatus)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025