JAPANESE CRAFTS

Japanese Buddhist altar The Japanese government officially recognizes almost 200 traditional national industries. They include doll making, origami, gold foil laquerwear, silk kimono painting, traditional dance, tea ceremony, flower arranging, ancient court music, bunraku puppetry, geisha girl dances, and Kabuki drama.

Smithsonian curator for ceramics Louise Allison Cort wrote, "Objects fashioned from diverse materials, serving both functional and ornamental purposes, have consistently played an important role in the material representation of culture values in Japan. In particular, Japanese makers and users of craft objects have contributed a distinctive vision of the emotional attributes of materials."

"Japanese crafts for secular use developed within an architectural setting consisting of fundamentally empty spaces defined by sliding, removable doors with no permanent freestanding furniture." Objects used in daily life were small and portable. "Built in architectural features...provided display space for a limited number of objects ta a given time...Objects were brought out of storage only as needed for work, entertainment, or display purposes. Such intimate force and portability were conducive to development of...Japanese luxury craft."

Japanese crafts reflect not only the period and place they are made but the climate of the place they are made and the personalities of their creators.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Traditional Crafts of Japan (Good, Detailed Site) kougei.or.jp ; Museum of Japanese Traditional Art Crafts nihon-kogeikai.com ; Craft Links japanesetemari.com/linksorientalculture ; American Society of Appraisers (to find the value of a Japanese craft) appraisers.org/ASAHome ; Japan -Shop.com japan-shop.com ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Lisa’s Japanese Pages lisashea.com ; Shibui Japanese Antiques shibuihome.com ;

Odds and Ends Asian Rare Books asianrarebooks.net/ ; Green Tea Design, Japanese and Korean Furniture greenteadesign.com ; Netsuke Carving, International Netsuke Society netsuke.org ; Temari Thread-Wrapped Balls japanesetemari.com ;

Kyoto and Tokyo Crafts: Welcome to Kyoto Kyoto Prefecture Site ; Japan Guide apan-guide.com ; Nishijin Textile Center Nishijin.or ; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Traditional Industry (near Heian Shrine) is a relatively new museum. Not only does it have exhibits of various handicrafts made of silk, bamboo, lacquer, paper and ceramics, it also features demonstrations of centuries-old production methods by skills craftsmen and craftswomen. kyoto.travel ; Nezu Institute of Fine Art (Minami Aoyama) is a two- gallery museum set around a traditional garden, with a charming and eclectic collection that dates from 2000 B.C. to the 1920s and includes hanging scrolls, tea ceremony utensils, screens, bronzes, lacquerware, ceramics, kimonos, Chinese bronzes, lacquered pillboxes, Japanese swords, and ink drawings by Kano Maonobu. Nezu Museum site nezu-muse.or.jp

Japanese Dolls Good Doll Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Japanese Dolls Page clas.ufl.edu/ ; Wooden Naruko Kokeshi Dolls /web-jpn.org/atlas ; All About Japanese Hina Dolls kyohaku.go.jp ; Kyoto Arashiyama Orgel (Moving Doll) Museum (in Japanese) orgel-hall.com ; Yokohama Doll Museum welcome.city.yokohama.jp ; Hakata Dolls, Fukuoka Tourist Information Site Fukuoka Tourist Information Site Expat’s Guide to Fukuoka May’s Fukuoka City Guide ; Fukuoka Tourism Fukuoka Sights

Japanese Swords Japanese Sword Guide earthlink.net/~steinrl/nihonto ; Blade Diagrams ksky.ne.jp ; Making the Blades www.metmuseum.org ; Wikipedia article wikipedia.org ; Katana Swords coldweapon.org ; Tokugawa Art sanmei.com/en-us ; Nihonto nihonto.ca ; Seto Cutlery Sword Site setocut.co.jp ; Bushido Japanese Swords bushidojapaneseswords.com ;

Samurai Armor, Weapons and Swords Gallery Samurai gallerysamurai.com ; Samurai Arms and Armor artsofthesamurai.com ; Kinokuniya Samurai Armor Shop www.kinokuniya.tv; Sokendo Samurai Armor Shop www.sokendo.net Armor from Clan Yama Kaminari yamakaminari.com ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ; Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EDO PERIOD ART Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UKIYO-E, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAPER CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEA CEREMONY AND FLOWER ARRANGING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Traditional Japanese Art and Crafts

tea ceremony tea whisks In Japan there isn't as clear a distinction between "pure art" and "functional arts and crafts" as there is the West, where painting and sculpture are generally lumped into the art category and basketmaking, ceramics and gardening are generally regarded as crafts or something else.

The Japanese did not make a distinction between the fine and applied arts until the 19th century. A famous art work in Japan is just as likely to be a fan or tea bowl as a painting or sculpture. Tim Clark, head of the Japanese section ay the British Museum, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Historically there is a very interesting cross-over between what in the West has been classified as fine art and craft. It’s a much less clear distinction in Japan. In fact traditionally those distinctions didn’t exist so much and I think that explains a lot of the formal strength and power of Japanese crafts.”

Clark also said, “What is very surprising and exciting to me is that perhaps in the West we think of “traditional” and “contemporary” as opposites in some way, whereas in so many pieces these two things are functioning at the same time...They are drawing on traditions and not only that but the traditions are constantly being updated each generation and often, in formal terms, you end up with something which seems very contemporary and visually very up-to-date and exciting.”

Many traditional Japanese art form-such as laquerwear painting and screen painting — require skills of a painter and craftsman. Many traditional Japanese arts and crafts are passed down from generation to generation by family member to family member or from teacher or master to student.

“Shi, Ha Ri” is a mantra repeated by traditional artists that encourage them rise above new works that transcend boundaries in pursuit of creativity.

Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties in Japan

16th century tea bowl The Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties of 1950 recognizes 1,054 artworks and building. The law defines the tangible cultural properties that are designated as such as buildings, artworks and documents that are deemed valuable from historic, artistic or academic standpoints.

The Japanese government officially recognizes almost 200 traditional national industries. They include doll making, origami, gold foil laquerwear, silk kimono painting, traditional dance, tea ceremony, flower arranging, ancient court music, bunraku puppetry, geisha girl dances, and Kabuki drama.

Today, many traditional art forms are dependent on government help for their survival, but even with subsidies, the art objects require so much skill and time to make, few people can afford them. A distinctive white-and-brown ceramic bowl, for example, costs around $220, and an originally crafted vase, $6,800. Kimonos that take months, even years to make, can cost on he hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Human Treasures in Japan

Some Japanese craftsman and artists are considered so skilled and talented, they are honored as Living National Treasures. Subsidized by the government and given the official title "Holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties," artist have be involved in a traditional craft, art or performing art to qualify.

As of 1990, 97 people had been named in the performing arts of kabuki, no and bunraku and 92 were named for their work in crafts such as ceramics, papermaking, weaving, swordmaking, and lacquer. One dollmaker who was recognized used to spend as much as 10 years working one a single doll. A Kabuki actor that was honored was the great-great-great-great grandson of a famous Kabuki actor. [Source: William Graves, National Geographic, September 1972]

The first Living Treasures were named in 1955 in accordance with Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties of 1950. The idea behind the human treasures belonged to, of all people, Douglas MacArthur, who was appalled by the destruction of priceless art during World War II, and wanted to make sure that Japan's ancient arts weren't lost and that the people who carried on the art forms were well taken care of.

Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu hemp textiles of Niigata Prefecture and Sekishu-banshi paper of Shimane Prefecture were added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2009.

See Separate Article JAPANESE ART, HUMAN TREASURES, FAMOUS COLLECTIONS AND ART RESTORATION factsanddetails.com

History of Japanese Crafts

2000-year-old Yayoi period vase Cort wrote: "Control of craft production has shifted over time, linked always to the social class most closely associated with economic power in patronage. From the 6th century through the 12th century, the government sponsored central workshops for craft production in luxury materials, including precious metals and lacquer. Other goods were sent to rulers."

"From the 12th through the 16th century, provincial warriors wielded increasing control over rural craft production such as ceramic, With the growth of markets and long-distance transportation, merchants assumed a central role in commissioning and distributing crafts from provincial as well as urban workshops. Kyoto...was known as the center of luxury crafts, especially lacquer and textiles."

"During the Edo period (1615-1868) military rulers sponsored specialty craft production within their domains, and "famous products: (“meibutsu”) became closely associated with specific locales."

Interest in traditional Japanese art forms is waning. According to a 1997 government White Paper on Leisure, twice as many women are more interested in personal computers than the tea ceremony and three times more would rather go bowling than engage in traditional flower arranging.

The market for craftsmen in also shrinking. Ota Ward in Tokyo has traditionally the home of small mon-and-pop style craft shops that produces all kinds of things. Between 1990 and 2000, the number of these workshops declined from 9,000 to 6,000.

Japanese Craftsmen

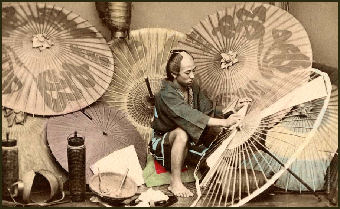

19th century umbrella craftsman The Western approach to craftsmanship is that some people have talent and some don't so that those with talent should be singled and nurtured. The Eastern approach is that most people have average talent but given the proper training they can become masters.

Many craftsmen comes from long lines of craftsmen who practiced the same craft. Traditionally the oldest son carries on the craft. If there is no oldest son then anther oldest son from a related family takes on role. The craftsmen were trained in apprenticeship system.

The traditional outfit of a Japanese craftsman is dark-blue “happi” (short coat) and matching pants. Sometimes they also wear shoes that separate the big toe form the other toes.

See Human Treasures, Above

Wood, Straw and Bamboo Crafts in Japan

Wood has traditionally been greatly prized in Japan and carpentry is a skill that ranks with pottery-making and other crafts. Particularly prized are small, austere chests called “tansu” that are skillfully joined pieces of wood and often have washi-covered panels. The most valuable of tansu — “Kaiden dansu” — resemble small flights of stairs (“kaiden” means "stairs").

Bamboo craftmaking is also a valued art form. Japanese bamboo baskets are among the finest in the world. They are famous for complexity of the weaving and delicacy of the finished work. Important tools in the tea ceremony such as ladles and whisks are made from bamboo.

Bamboo is said to have "1,400 practical and decorative uses" in Japan. The traditional wood and paper Japanese house utilizes bamboo in ceilings, moldings, rain spouts and gutters. Baskets, flutes, dolls, chairs and countless other objects are made from bamboo. It is even possible for a man to buy a five foot long bamboo wife which he throws over one leg to keep cool on summer nights. [Source: Luis Marden, National Geographic, October 1980]

Straw models of “takarabune”, mythical treasure ships that carry the Seven Gods of God Fortune, are a specialty of Itoigawa in Niigata Prefectures. A traditional New Year’s gift, they are made of rice straw and decorated with artificial pine, bamboo and plum and decked with bales or rice, a folding fan, artificial red bream, gold coins and mizuhiki paper cords. Other decorations made from straw include models of cranes and tortoises. Straw raincoats and sandals were used for hundreds of years. Straw ropes were put all kinds of different uses by farmers.

Traditional Japanese Brushmaking

Motoki Nakajima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “A bundle of bristles clutched in his hand, Akio Miyakawa swiftly hooks the fibers to a stainless steel wire and threads the bunch through a tiny hole in a wooden head. He repeats the action, the bristles are sucked into rows of holes one after another. A brush begins to take shape.” [Source: Motoki Nakajima, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 23, 2011]

The 86-year-old brushmaker has been recognized as a "contemporary master craftsman" by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry. He works from his shop, the Miyakawa brush factory, which first opened in 1923. Partly facing Asakusa street in Taito Ward, Tokyo, the area used to be bustling with shops run by various types of craftsmen. Miyakawa's handmade brushes have been designated a traditional craft by the Tokyo metropolitan government. He uses animal bristles for his brushes and favors pig bristles because of the way they curve. The bristles are a little more resilient and flexible than other kinds.

The master craftsman is one of only a handful of people remaining who are skilled in making handmade brushes. Although it has become more common for brushes to be made by machine, Miyakawa says he sticks to traditional methods so he can change the materials and production technique for each brush depending on his customers' needs. Each brush is discreetly branded with Miyakawa's name. He makes different brushes for a variety of uses--for personal use (shaving and makeup brushes for the face; scrubbing brushes for the body), for improving the appearance of one's clothing or shoes, or for cleaning, such as scrubbing the floor.

Miyakawa says that unlike their machine-made counterparts, handmade brushes rarely lose their bristles, which the tip of the brush won't crack. Handmade brushes can last about 50 years. "The most important things is to gain trust from customers," the craftsman smiles. "I'll continue making brushes as long as my body allows me."

Japanese Hand-made Combs

Miwa Uehara wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Boxwood combs--tsuge no kushi in Japanese--have long been part of a beauty kit for women in this country. Jusanya, a store that was founded in 1736 in Ueno, Tokyo, still makes such combs. All the combs are handmade by Tsutomu Takeuchi, 70, the 14th-generation owner of the store near Ueno's Shinobazu no ike pond, and his son, Keiichi, 44. [Source: Miwa Uehara , Yomiuri Shimbun, July 6, 2012]

The store uses wood from boxwood trees cultivated in the Satsuma region in Kagoshima Prefecture. "Boxwood has a good consistency, springiness and density that is perfect as a material to make pliable combs," Keiichi Takeuchi said. "No wood is better than boxwood grown in Japan." However, as a lot of work is required to make sure boxwood trees grow well, there is a shortage of the right timber. "Boxwood is traditionally considered a luxurious type of wood," Takeuchi said. "It used to be the custom for brides to include boxwood combs in their trousseau when they married.”

There are two main types of combs in daily use. A crescent-shaped comb is used to comb through the hair, while a rectangular one with a handle would be used to pile up the hair or set a hairstyle. Jusanya usually makes crescent-shaped combs.The types of combs differ depending on the length, thickness and nature of the user's hair. The purchaser should check first to see how easily it sits in the hand before buying it. "A bigger comb is naturally heavier, and it slides more easily through the hair without pulling it," Takeuchi said. "Whether you want wider gaps between the teeth of a comb is up to you. I give my customers advice depending on the nature of their hair.”

But regardless of the shape or weight, it takes more than 60 steps to make a comb out of the branch of a boxwood tree. He insisted the comb's color improves the more it is used. "It'll shine, too," he added. I borrowed a comb that had a whiff of camellia oil. The teeth touched my scalp softly as the comb slid firmly through my hair. Takeuchi said a comb becomes more suitable for a woman's hair the longer she uses it.

Fingernail Art in Japan

In Kyoto, you can still find master weavers who practice “tsuzure-ori” (fingernail weaving), an art form, dating back to perhaps the 5th century A.D., in which weavers creates intricate detailed designs woven with a dozen or so grooves notched into their fingernails. Obis (sash-like belts worn with a kimono) made with tszure-ori sometimes sell for over US$10,000 and take a year to make. [Source: Nina Hyde, National Geographic, January 1984]

The edge of the index, middle and third of both hands resembles saw edges. They are are used to collect colored weft yarn to create lifelike patterns and designs. Saeko Watanabe, a fingernail weaver from Kyoto, specialized in weaving obis and original textiles inspired by ukiyo-e and nishiki-e woodblock prints. She used more than 200 colors and creates hues by splitting thread in half and combining then with differently colored thread. It can take more than a day to weave a single centimeters of a design with fine color gradations. [Source: Daily Yomiuri]

Watanabe told the Daily Yomiuri she uses her fingernails as opposed to a guitar pick or a koto plectrum . She said there is no substitute for fingernails, which allow her to feel the threats’ “life force” and enable her to weave as though she was “drawing a picture with thread.”

Needles and Fishing Rods in Japan

artist-made fishing lures There is a family in western Japan has been making sewing needles for nineteen generations, and fishhooks since the 1700s. In feudal times, their products were considered so good that they earned the surname "narrow-eyed needle," an unusual honor at that time. The family also makes top-of-the-line lacquered bamboo fishing rods take two years to make. They hope to sell some of these rod in the United States. [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic, September 1994]

The oldest member of the family, who is 82, was recently joined by his 49-year-old-son, retired flight steward for Japan airlines, who hopes to market the rods in America. "We already have the old man's craftsmanship, and I have a modern sense of the sport" says the son, who has fished all over the world. "We have to add new elements to keep the tradition alive. Otherwise, you're making antiques." [Source: Smith]

Quality bamboo fishing rods made by Kisaburo Nakane, a forth generation rod maker, who works out of the Saochu tackle shop in Tokyo makes traditional Edo-style rods using 120 processes, including cutting and heating the bamboo and applying. It takes three months to a year to make such a rod. 30 coast of lacquer Baleen from bowhead whales to transfer delicate vibrations down the rod to the fisherman’s hands.

The making of flies and lures is also a an art form practiced by skilled craftsmen. Lures to catch “ayu”, or sweetfish, is a specialty of Kanazawa. They are made from one-centimeter long hooks and gilded led balls that have different kinds of feathers and different colored threads tied to them. Different patterns are used depending on the temperature, sunlight and water conditions. One store in Kanazawa that has been open since 1575 offers 900 different lures. The owners recommends using red lures in the morning and blue or green ones in the afternoon.

Japanese Mirrors

bronze mirror Metalworkers in Kyoto still make bronze mirrors like the earliest mirror made in ancient China and Greece, These mirrors, like ones created in medieval times, are almost as reflective as modern mirrors. Ones made by skilled craftsmen cost as much as $10,000 a piece.

To make a bronze mirror one first has to create a mold. If the mirror back has a lot of designs, the mold can take a considerable amount of time to make. Once the mold is complete bronze or cupronickel melted at a temperature of around 1200 degree C is cast in the mold. After the mirror is hardened and removed their reflective surface s created with five polishing procedures. Nickel plating is then applied to make surface perfectly smooth.

A “makyo” mirror is a special mirror that appears perfectly smooth, but when a bright light is shined on it, an inscribed image can be seen in its reflected image in a wall. The image is usually spiritual symbol of some kind. To make such a mirror the design is created on the side of a sheet of metal. The other side which becomes the front of the mirror us is buffed for a considerable amount of time until the thickness of the mirror is reduced to less than a millimeter so the image appears when light strikes it.

Mirrors have a long association with Japanese religion. They are among the most scared objects in Shintoism, with a special mirror for the Japanese Emperor kept in Ise Grand Shrine in Mie Prefecture. Early Christians kept makyo mirrors with Christian symbols because they could hide the images.

Lowriders and Decorated Trucks in Japan

Decorated trucks are regarded as a kind of modern folk art in Japan. Some spend hundreds of thousands of dollars customizing their trucks: adding platform-like extensions on the front bumper, placing gabled roofs over the cabs and putting rows of colored lights running along every edge and contour. Inside additions include embroidered upholstery tatami floor panels, and even chandeliers. Some have elaborate paint jobs on the side panels — which include images of dinosaurs, dragons, wildcats, sword-wielding samurai, kimono-clad women and religious imagery — and names that are printed in several places on the truck.

Lowriders, street-hugging cars with hydraulic lifts that are popular among the Latin and black communities in Los Angeles is one of the oddest American fads to catch on in Japan. A typical 1960s Chevy Impala outfit with a lowriding suspension that can make a car jump and down sells for $5,000 to $15,000 in the U.S., but goes for between $25,000 and $35,000 in Japan.

The popularity of lowriders is a result of the importation of rap culture, whose videos often feature low riders. The number of lowriders has increased from 300 in 1992 to 3,000 in 1996. The are clubs, shops, and magazines geared towards lowrider enthusiasts. Brokers who import low-riders from California to Japan say they make about $2,000 on each vehicle.

Many lowrider vehicles are too big for Japan's roads. You rarely see them on the streets and owners need to have them trucked to lowrider gatherings. Many lowrider enthusiasts are blue collar workers who are fascinated by American lowrider culture.

Japanese Sculptor to Create Doors for Sagrada Familia

In September 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Sculptor Esturo Sotoo has announced he will create four doors that will be attached to the Nativity Gate of Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi's unfinished masterpiece, the Sagrada Familia church in Barcelona. Sotoo, 59, said the work would be completed in 2015 and is part of a series of projects commemorating the 400th anniversary of Japan-Spain relations. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 25, 2012]

The church's Nativity Gate and crypt were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Gaudi's other works in 2005. The doors, which will be made of bronze, will stand at about five to seven meters tall and be decorated with plant and insect designs, Sotoo said. The doors will be cast in Japan and painted in Spain.

Image Sources: National Museum in Tokyo, British Museum, Association for the Promotion of Traditional Crafts Industries in Japan, JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013