HEADHUNTING IN BORNEO

Headhunting has traditionally been practiced by many of Borneo ethnic groups, including the Dayak tribes, the Iban, Kayan, Kenya. Most of the heads have traditional been collected in highly ritual raids. The Very Rev. Thomas Jackson wrote in “Perfect Apostolic of Labuan and North Borneo, 1884": "They have a custom of killing people in order to obtain human skulls, which they suspend as trophies from the roofs of their huts. It is from this custom these people have obtained the name of “Head Hunters”. But, not withstanding the barbarous customs that exist amongst them, they have many good qualities."

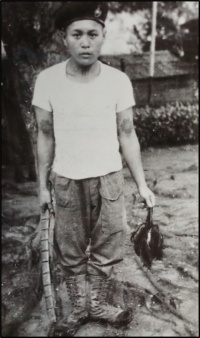

Skulls from headhunting raids have traditionally been displayed in longhouses. Some longhouses today still have heads hanging from the ceiling as relics of their glorious past. The most recent ones are Japanese heads taken in World War II.

Headhunting was outlawed by the Dutch and the British on Borneo in 19th century but continued. Head hunting decreased over time, in part because of peace agreements in 1894 and 1924. In the 1940s, the Dutch made a major effort to crackdown on headhunting. Head parties were gaoled (places in chains).

In the mid 40s there was a spike in the number of head hunting occurrences as the Allies encouraged any means to defeat the Japanese. There was another increase in the 60s when the Indonesian government, fearing the spread of communism, encouraged the head hunting of Chinese immigrants. Headhunting is believed to still be practiced in some remote areas. In the coastal town of Balikpapan in Kalimantan, Indonesia in the 1970s, Dayaks purportedly attacked employees at a Javanese sawmill and separated several of them from their heads. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

RELATED ARTICLES:

VIOLENCE AGAINST THE MADURESE IN BORNEO factsanddetails.com

LATER BORNEO HISTORY: COLONIALISM, BRITAIN, DUTCH, MALAYSIA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

JAMES BROOKE AND MAKING NORTHERN BORNEO PART OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FIGHTING WITH BORNEO PIRATES factsanddetails.com

EARLY BORNEO HISTORY: FIRST PEOPLE, AUSTRONESIANS, TRADE factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO: GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, STATES, TRAVEL factsanddetails.com

BORNEO BIODIVERSITY: RAINFORESTS, NEW, RARE SPECIES, THREATS factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Methods of Taking Heads

According to an official of the Sarawak Government Service: “The way of cutting off their heads varies with the different tribes. The Sea Dyaks (Iban), for instance, sever the head at the neck, and so preserve both jaws. Among the Hill Dyaks (Kelabit, Kenyah and other tribes), on the other hand, heads are very carelessly taken, being split open or slashed across with parangs. Often it may be seen that quite large portions have been hacked out of the heads. Others again cut off the head so close to the trunk that great skill and a practised hand must have been used. [Source: flyingdusun.com ]

“Many tribesmen habitually carry about their person a little basket destined to receive a head. It is always very neatly plaited, ornamented with a variety of shells, and hung about with human hair. But only those Dyaks who have lawfully obtained such a head, as opposed to those who steal, or "find" them, may include this human hair ornamentation to their macabre baskets.

“The Sea Dyaks scoop out the brains by way of the nostrils, and then hang up the head to dry in the smoke of a wood fire - usually the fire which is maintained anyway for the cooking of all the food for the members of the tribe. Every now and then they will leave their preoccupations, saunter across to the fire, and tear or slash off a piece of the skin and burnt flesh of the cheek or chin, and eat it. They believe that by so doing they will add immediately to their store of courage and fearlessness. The brains are not always extracted by way of the nostrils, however. Sometimes a piece of bamboo, carved into the semblance of a spoon, is thrust into the lowest part of the skull, and the brains gradually extracted by the occipital orifice.”

Flyingdusun.com reported:“Talking to various elderly Kadazan here in Sabah it seems that they needed to sever the head of their enemy while he was still alive, preferably in combat. The head of an already dead man or woman was considered ‘useless’ because devoid of any spirits: the Kadazan, and other Dusunic ethnic people believe that our body is maintained by a number of specialised spirits that inhabit our body, the Rungus call them 'hatod'. There are spirits looking after our knees, others after our chest and so on. The most important spirit is of course located in the head - the 'lugu' in Rungus, or 'tandahau' in Kadazan. My friends have reasoned with such – admittedly logical – arguments as: “if you lose a leg, or an arm, you can still live, but when you lose your head, or got a major injury to your head you die…!” “When someone dies,” the stories continue, “our ‘maintenance spirits’ reassemble, go to Mt Kinabalu and eventually find themselves back on the earthly plain in the body of a newborn. If a human head is severed the body maintenance spirits leave through the wound the decapitation created, but without the head spirit which has rolled away with the head and finds itself alone and confused. It remains in the severed head hoping that someone will take care of it.” And that is exactly what the Kadazan did: the head was brought to the village, displayed in a bangkaha – a peculiar bamboo contraption for sun drying enemy heads – and then welcomed in a grand ceremony that aimed at making the spirit forget, forgive and feel at home in its new place.

Reasons for Head Hunting

Heads taken in headhunting raids brought glory to the warrior who collected them and good luck to their village. They were usually preserved and worshiped in special rituals. Certain parts of the body—the heart, brains, blood and liver—was believed to bring power to those who consumed them. Some Dayaks of Sarawaks used to eat the palms of their enemies. Cutting out the heart, it was believed, destroys the evil that is believed to reside in that organ.

Most heads are taken out as an act of revenge, often for the breaking of “adat” ("traditional law"). A Catholic Dayak teacher told the Independent, "In the eyes of the Dayaks when people do not respect our adat, they become enemies, and we don't consider our enemies to be human any more. They become animals in our eyes. And the Dayaks eat animals." Richard Lloyd write in the Independent, "Decapitation and cannibalism are the deeply symbolic practices, the ultimate humiliation of a defeated enemy. Cut someone's head off and you reduce him to a pantomime mask. This is the point about severed heads—they don't look fearful so much as comical, like Halloween pumpkins.”

On Seribas Dayak headhunting, Sir Spencer St. John wrote: A certain influential man denied that head-hunting is a religious ceremony among them. It is merely to show their bravery and manliness, that it may be said that so-and-so has obtained heads. When they quarrel it is a constant phrase, “How many heads did your father or grandfather get?” If less than his own number, “Well, then, you have no occasion to be proud!” Thus the possession of heads gives them great considerations as warriors and men of wealth, the skulls being prized as the most valuable of goods. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Feasts in general are: To make their rice grow well, to cause the forest to abound with wild animals, to enable their dogs and snares to be successful in securing game, to have the streams swarm with fish, to give health and activity to the people themselves, and to insure fertility to their women. All these blessings the possessing and feasting of a fresh head are supposed to be the most efficient means of securing.

Dalrymple wrote: The Uru Ais believe that the persons whose heads they take will become their slaves in the next world. Roth states: From all accounts there can be little doubt that one of the chief incentives to getting heads is the desire to please the women. It may not always have been so and there may be and probably is the natural blood-thirstiness of the animal in man to account for a great deal of the head-taking.

Borneo Spirituality and Head Hunting

According to Discover Malaysia: “Within the complex polytheist and animist beliefs of the Dayaks, beheading one’s enemy was seen as the way of killing off for good the spirit of the person who had been killed. The spiritual significance of the ceremony also lay in the belief that at the end of mourning for the community's dead. The heads were put on display at traditional burial rites, where the bones of relatives were dug out from the earth and cleaned before being put in burial vaults. Ideas of manhood were also bound up with the practice, and the taken heads were surely a reward.”

Some Borneo tribal people also believe that head hunting helps soil fertility and give a person strength. Heads are sometimes used as a dowry, to strengthen buildings, protect against attacks, and display status. Some groups hunted heads primarily for ceremonial purposes. The heads are believed to possess magical powers and even today are sometimes brought out during important weddings, births and funerals. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

In the old days, when a prospective groom returned with a head he tied it to the head of his bride. During a three day ceremony animals are sacrificed, rituals are conducted and the organs of sacrificed animals are read for omens by a shaman. If the readings are satisfactory the shaman proclaims the transfer of the soul a success. If not the prospective husband must come up with a new head. When these groups moved they always took their hunted heads with them. Occasionally the heads were rolled in ashes to make sure that their soul didn't leave and torment the hunter. ♢

Headhunting Legends and Stories

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: F. F. McDougall in her statement of a Sakaran legend of the origin of head-taking to the effect that the daughter of their great ancestor residing near the Evening Star “refused to marry until her betrothed brought her a present worth her acceptance.” First the young man killed a deer which the girl turned from with disdain; then he killed and brought her one of the great monkeys of the forest, but it did not please her. “Then, in a fit of despair, the lover went abroad and killed the first man he met, and, throwing his victim’s head at the maiden’s feet, he exclaimed at the cruelty she had made him guilty of; but, to his surprise, she smiled and said that now he had discovered the only gift worthy of herself”. In the three following pages of his book the author quotes three or four other writers who cite in detail instances wherein heads were taken simply to advance the slayer’s interests with women. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

As showing the passion for head-hunting among these people, St. John tells of a young man who, starting alone to get a head from a neighboring tribe, took the head of “an old woman of their own tribe, not very distantly related to the young fellow himself.” When the fact was discovered “he was only fined by the chief of the tribe and the head taken from him and buried”...The maxim of the ruffians (Kayans) is that out of their own country all are fair game. “Were we to meet our father, we would slay him.” The head of a child or of a woman is as highly prized as that of a man.

Mr. Roth writes that Mr. F. Witti “found that the latter (Limberan) would not count as against themselves heads obtained on head-hunting excursions, but only those of people who had been making peaceful visits, etc. In fact, the sporting head-hunter bags what he can get, his declared friends alone excepted”.

Dusun Headhunting

Headhunting was practiced by the Dusun up until World War II even though the practice was outlawed by the British in the late 19th century. It was usually the climax of a conflict between communities that was solved through raiding and hand to and combat.

Traditionally, conflicts were often the result of a perceived imbalance, disharmony or ill fortune in one community believed to be the caused an individual in another community. The Dusun organized raiding parties of men who sought hand-to-hand combat with individuals, social groups, or entire communities believed to have caused an imbalance in personal or communal fortune (nasip tavasi) and luck (ki nasip). Such armed confrontations were generally undertaken to restore the fate or luck of individuals or communities that had been rendered unfavorable (aiso nasip, talat) through the actual or perceived actions of others.

The object of raids was to secure trophies, preferable the heads of enemies killed in close combat which could be publicly displayed as symbols of the successful restoration of good fortune and luck. Heads taken in this way were treated with great reverence and special care. They were usually stored in a special place, including the eaves of houses, and were used for special rituals in which they were the focal point and regarded as integral to maintaining harmony.

See Separate Article: DUSUN factsanddetails.com

Iban Headhunting

Charles Hose, an Englishman stationed on Borneo as the Resident Magistrate during British Imperial rule in the early 20th century, described Iban headhunting in his book, “The Pagan Tribes of Borneo”, published in 1912: “It is clear that the Ibans are the only tribe to which one can apply the epithet head-hunters with the usual connotation of the word, namely, that head-hunting is pursued as a form of sport.” He also said these same people “are so passionately devoted to head-hunting that often they do not scruple to pursue it in an unsportsmanlike fashion.”[Source: discover-malaysia.com]

Hose believed the Ibans probably “adopted the practice [of headhunting] some few generations ago only... in imitation of Kayans or other tribes among whom it had been established,” and that “the rapid growth of the practice among the Ibans was no doubt largely due to the influence of the Malays, who had been taught by Arabs and others the arts of piracy.” As their own areas became overpopulated, they were forced to intrude on lands belonging to other tribes to expand their own land-trespassing which could only lead to death when violent confrontation was the only means of survival.

On why the practice of headhunting existed, Hose wrote: “That the practice of taking the heads of fallen enemies arose by extension of the custom of taking the hair for the ornamentation of the shield and sword-hilt,” and that: “The origin of head-taking is that it arose out of the custom of slaying slaves on the death of a chief, in order that they might accompany and serve him on his journey to the other world.”

See Separate Article: IBAN factsanddetails.com

Headhunting Today

Flyingdusun.com reported: In many parts of contemporary Borneo headhunting is a part of the past preserved in narrative form and in some areas headhunting rituals continue. While in olden days fresh heads were required for certain ceremonies ‘old’ skulls may now be used as replacement, or the skulls of orang utan and even wooden substitutes or coconuts. This is in areas where head-hunting rituals are needed for spiritual benefits such as for agriculture (rice) and the building of a new house (longhouse). In the case of the direct descendants of the Kadazan warrior Monsopiad, yearly simple rites are conducted to maintain and ensure the ‘happiness’ of his 42 skulls and the spirits dwelling therein. The yearly rites were completed with a major ceremony (momohizan) that recurred every five to seven years. The ceremony lasted over several days and was very costly because the whole family had to be gathered, plus of course many friends and all had to be served foods and drinks. It was essentially a very prestigious event for the ‘guardian of skulls’ and his family, where the spiritual purpose outweighed the cost. In fact, the ritual was necessary in order to maintain and renew the spiritual/magical bonds with the otherworld. With the disappearance of the last Bobohizan – the Kadazan ritual specialists – the present keeper of skulls and 6th direct descendant of Monsopiad is worried that the spirits inhabiting the skulls will resort to mischief. The simple ceremonies in order to keep the spirits ‘calm’ must still be conducted on a yearly basis, and certain taboos must be observed by those wishing to see the skulls. [Source: flyingdusun.com ]

“To-day, headhunting has officially disappeared. The last to give up the old custom in Sabah were the Murut, because their main reason for headhunting – initialisation into manhood – was more on a spiritual level than the Kadazandusun headhunting which primarily occurred during territorial disputes. The Kadazan passed their ancestors’ skull collection on to new generations who maintained the spirits in the skulls. Thus they had no need to add regularly to the collection, whereas each Murut man needed to prove his manhood with the killing of at least one person and show the skull for proof. [Ibid]

“Headhunting was reportedly revived during WWII when the Japanese occupied Borneo. In fact, the English encouraged the locals on a guerrilla war against the Japanese, and paid for every enemy head two shilling*. Rumours persist of modern-day headhunting, of course. It is said that when a new bridge is built, a head (or several, depending on the size of the bridge) is needed in its fundaments. Prolonged draught and other natural calamities also may require a human sacrifice to calm nature and reinstall harmony between mankind, nature and the astral world. When in a faraway village people advise you to lock all doors and windows in the night, or if they insist that you sleep with them in the same room as they do, simply don’t ask. [Ibid]

Severed Heads and Violence Against Madurese in Borneo

In recent times, beheading by Dayak people resurfaced in Kalimantan, the Indonesian portion of Borneo, during brutal outbreaks of ethnic violence in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In 2001, over 500 Madurese immigrants were killed and tens of thousands forced to run away, with the bodies of some victims decapitated in rituals. Conversion to Islam or Christianity and anti-headhunting legislation by the colonial powers were supposed to have wiped out headhunting.

On violence in December 1996, Sinapan Samydorai of Human Rights Solidairty wrote: “Initially the ethnic conflict between the indigenous Dayaks and migrants from Madura Island occurred in the Sanggu-Ledo District, about 100 kilometers north of the provincial capital Pontianak, West Kalimantan. The Dayaks rioted over the failure of local police to prosecute a Maduran man accused of raping a Dayak woman. The Dayaks later killed the Maduran man, inciting violent retaliations and provincewide conflict. The Dayaks of West Kalimantan have more confidence in adat, their own traditional tribal laws, than in the national police and justice system. The Dayaks also complain that migrant workers receive preferential treatment by local officials and are rarely prosecuted for breaking the law. The attacks are being waged using traditional rules: a life for a life. An offense against an individual is an offense against the whole tribe. [Source:Sinapan Samydorai, Human Rights Solidairty, August 14, 2001^|^]

During one week in March 1999, 73 people were killed in rural areas around the town of Singkawang in West Kalimantan. Many of the dead were horrible mutilated and their body parts were paraded around and displayed. Witnesses reported that Dayaks and Malays decapitated three Madurese, and parading their heads through the town of Tebas. The body of one man was cooked in the marketplace and small pieces of his liver were offered to bystanders. Many people accepted. Dayaks have traditionally believed that eating one's enemy allows one to absorb their courage.

During the wave of violence Dayak paraded through the streets carrying severed ears, arms and heads. CNN videotaped images of dismembered bodies with their hearts cut out and boys playing soccer with a decapitated head. The Independent reported a laughing man with a severed arm posing for photographs with it as if it were a trophy fish. Richard Lloyd Parry of the Independent wrote, "I saw my sixth and seventh heads...in a Dayak village...They were visible from a few hundred yards away, standing on oil drums, with a crowd of about 200 people milling around...In the past six days I have seen seven of them, along with a severed ear, two arms, and numerous pieces of heart and liver, and a dismembered torso cooked over a fire by the side of the road. They look like all the other heads I had seen...They were a middle aged couple, a few years younger than my own parents. Their ears and lips had been shaved off with machetes, giving them a snarling sub-human look. The wife's nose had also been removed, and a cigarette had been pressed into the cavity. Her eyes were clenched tight shut, and above them an atrocious wound had been cut deep into her forehead."

Parry met one man with a machete with a red painted handle carved in the shape of a horse. Tied to his belt was transparent bag with some liver in it. He said the liver came from a body they cooked on the side of the road. "We killed it and we ate it," he said, "because we hate the Madurese. Mostly we shoot them first, and we chop the body. It tastes just like chicken. Especially the liver—just the same as chicken." The man then explained he didn't kill babies and children had to be around 13 or 15 before he would kill them. After the man left, Lloyd' driver told him, "You know I've been all over this country—to Sumatra, to Java...and these people—they're the nicest, the friendliest, the best."

See Separate Article: VIOLENCE AGAINST THE MADURESE IN BORNEO factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026