SRIVIJAYA EMPIRE

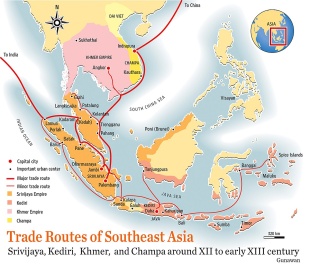

The Hindu-Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya was the first major Indonesian kingdom and the first major Indonesian commercial sea power. Ruled by Tamils and centered in Palembang, on the Musi River in present-day Sumatera Selatan Province, it was founded in Sumatra the end of the 6th century after Funan had been conquered and thrived from the 8th to 13th centuries.. At its height, it ruled Western Indonesia and controlled the strategic Molucca Straits—a choke point on the India-China trade route— and much of the trade in the area. Although historical records and archaeological evidence are scarce, it appears that by the seventh century A.D., the Indianized kingdom of Srivijaya, centered in the Palembang area of eastern Sumatra, established suzerainty over large areas of Sumatra, western Java, and much of the Malay Peninsula.[Sources: Library of Congress, noelbynature, southeastasianarchaeology.com, June 7, 2007]

Srivijaya means “shining victory”. It was a Malay polity and a Hindu-Buddhist trading kingship ruled by the Maharajahs of Srivijaya. The empire was based around trade, with local kings (dhatus or community leaders) swearing allegiance to the central lord for mutual profit. Srivijaya’s area of influence included neighbouring Jambi, to the north the kingdoms of the Malay Peninsula: Chitu, Pan-pan, Langkasuka and Kataha, as well as eastwards in Java, where links with the Sailendra dynasty and Srivijaya are implied. The same Sailendra dynasty was responsible for the construction of the massive Buddhist stupa of Borobudur between 780 and 825 AD.

Srivijaya was a large empire that endured for around 600 years but remarkably evidence of it was only unearthed relatively recently. The first hint of a Sumatran-based polity was first alluded to by the eminent French scholar George Coedes 1918, based on inscriptions found in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Although surviving records about Srivijaya are limited, it is clear that the empire dominated the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and western Java for nearly five centuries. Its decline began as Chinese shipping expanded throughout the archipelago, revitalizing Malay, Thai, and Javanese ports and dispersing the influence once held by Palembang.

Books: 1) “Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History” by P. S. Bellwood and I. Glover (Eds) contains chapters on the classical cultures of Indonesia and the archaeology of the early maritime polities of Southeast Asia; 2) “Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula by P. M. Munoz; 3) “Early History (The Encyclopedia of Malaysia) by Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman (Ed) has several chapters on Srivijaya; 4) “Sriwijaya: History, religion & language of an early Malay polity by G. Coedäs and L. Damais; 5) Wolters, O. W. Early Indonesian Commerce: A Study of the Origins of Srivijaya. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967. 6) Wolters, O.W, The Fall of Srivijaya in Malay History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1970.

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MATARAM KINGDOM: HISTORY, HINDUISM, PRAMBANAN, AFTERWARDS factsanddetails.com

SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

SINGHASARI, KEDIRI, MARCO POLO AND THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAVA factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

Mataram and Srivijaya

Another kingdom—Mataram— arose as Srivijaya began to flourish in the early eighth century, in south-central Java on the Kedu Politically, the two hegemonies were probably more alike than different. The rulers of both saw themselves and their courts (“kedatuan”, “keratuan”, or “kraton”) as central to a land or realm (“bhumi”), which, in turn, formed the core of a larger, borderless, but concentric and hierarchically organized arrangement of authority. In this greater mandala, an Indic-influenced representation of a sort of idealized, “galactic” order, a ruler emerged from constellations of local powers and ruled by virtue of neither inheritance nor divine descent, but rather through a combination of charisma (“semangat”), strategic family relationships, calculated manipulation of order and disorder, and the invocation of spiritual ideas and supernatural forces. [Source: Library of Congress*]

The exercise of power was never absolute, and would-be rulers and (if they were to command loyalty) their supporters had to take seriously both the distribution of benefits (rather than merely the application of force or fear) and the provision of an “exemplary center” enhancing cultural and intellectual life. In Mataram, overlords and their courts do not, for example, appear to have controlled either irrigation systems or the system of weekly markets, which remained the purview of those who dominated local regions (“watak”) and their populations. This sort of political arrangement was at once fragile and remarkably supple, depending on the ruler and a host of surrounding circumstances. *

Very little is known about social realities in Srivijaya and Mataram, and most of what is written is based on conjecture. With the exception of the religious structures on Java, these societies were constructed of perishable materials that have not survived the centuries of destructive climate and insects. There are no remains of either palaces or ordinary houses, for example, and we must rely on rare finds of jewelry and other fine metalworking and on the stone reliefs on the Borobudur and a handful of other structures, to attempt to guess what these societies may have been like. A striking characteristic of both Srivijaya and Mataram in this period is that neither—and none of their smaller rivals—appear to have developed settlements recognizable as urban from either Western or Asian traditions. On the whole, despite evidence of socioeconomic well- being and cultural sophistication, institutionally Srivijaya and Mataram remained essentially webs of clanship and patronage, chieftainships carried to their highest and most expansive level. *

Srivijaya Buddhist Culture

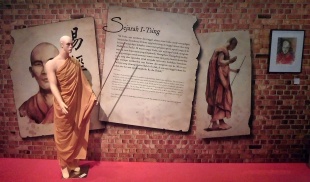

Srivjaya was a Buddhist kingdom. The Srivijaya kings practiced Mahayana Buddhism which suggests its introduction from India. As a stronghold of Mahayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk and pilgrim Yijing and the eleventh-century Buddhist scholar Atisha, who played a major role in the development of Tibetan Buddhism. In the 8th century Srivjaya introduced a mixture of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism to Malaysia and Thailand. [Sources: Library of Congress, noelbynature, southeastasianarchaeology.com, June 7, 2007]

Srivijaya was considered to be one of the major centres of learning for the Buddhist world. Yijing (635–713), who briefly visited Srivijaya in 671 and 687 and then lived there from 687 to 695, recommended it as a world-class center of Buddhist studies. Inscriptions from the 680s, written in Pallava script and the indigenous Old Malay language (forerunner of contemporary Bahasa Indonesia), identified the realm and its ruler by name and demanded the loyalty of allies by pronouncing elaborate threats and curses. [Library of Congress]

Yijing travelled between China and India to copy sacred texts mentioned the high quality of Sanskrit education at the Srivijayan capital of Palembang, and recommended that anyone who wanted to go to the university at Nalanda (north India) should stay in Palembang for a year or two to learn “how to behave properly”. Asia. In 671, Yijing reported that around 1,000 monks from various countries were studying Buddhism—particularly Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions—in Palembang.

Yijing wrote in “A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea”: "Many kings and chieftains in the islands of the Southern Ocean admire and believe (Buddhism), and their hearts are set on accumulating good actions. In the fortified city of Bhoga [Palembang] Buddhist priests number more than 1,000, whose minds are bent on learning and good practices. They investigate and study all the subjects that exist just as in the Middle Kingdom (Madhya-desa, India); the rules and ceremonies are not at all different. If a Chinese priest wishes to go to the West in order to hear (lectures) and read (the original), he had better stay here one or two years and practise the proper rules and then proceed to Central India."

Srivijaya’s prominent role in the Buddhist world can be found in several inscriptions around Asia: an inscription in Nalanda dated 850-860 AD described how a temple was built in Nalanda at the request of a king of Srivijaya. In the 11th century, a temple in Guangzhou in China received a donation from Srivijaya to help with the upkeep. The Wiang Sa inscription quoted above recounts how a Srivijayan king ordered the construction of three stupas in Chaiya, also in the Thai peninsula.

Srivijaya Art and Architecture

Srivijaya was a crucial hub for the spread and exchange of Buddhist culture. It served as a key intermediary between India and China. Its renowned monasteries drew Buddhist scholars from across Asia. As a major maritime hub, Srivijaya played a crucial role in transmitting Buddhist art, ideas, and ritual objects throughout Southeast Asia—from the Malay Peninsula to Thailand and Sumatra. Its distinctive quadrangular clay votive tablets depicting Mahayana deities became especially widespread, testifying to the empire’s cultural influence and the enduring legacy of its Buddhist traditions.

As we said before With the exception of the religious structures on Java, structures were constructed of perishable materials that have not stood the test of time and don’t exist today. There are no remains of either Srivijaya palaces or ordinary houses. We must rely on rare finds of jewelry and other fine metalworking (such as the famous Wonosobo hoard, found near Prambanan in 1991), and on the stone reliefs on the Borobudur and a handful of other structures, to attempt to guess what these societies may have been like.

Srivijayan Buddhist art reflects its cosmopolitan influence. A notable example is an image of the Bodhisattva Manjushri, which belongs to the Srivijayan sculptural tradition but displays strong similarities to Indian Pala-period works, evident in the gently swaying posture and the lotus throne with its distinctive pearl-edged rim. The chedi of temples produced during the Srivijaya period resemble Hindu-Buddhist stupas of central Java which have a ‘stacked” appearance. This style was copied in Thailand, including at temples in the great Thai kingdom of Sukothai (m 1238 until 1438). [Source: Asia Society Museum]

Srivijayan art and architecture blended Indian influences—especially from the Gupta and Pala traditions—with local aesthetics, producing a distinctive Mahayana Buddhist style that spread across maritime Southeast Asia. Although most of its physical structures have not survived as well as those in Java, Srivijaya is known for graceful bronze and stone sculptures of Bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, often depicted with haloes, intricate jewelry, and richly detailed garments. The kingdom made extensive use of bronze, gold, and silver for religious images and ceremonial regalia, alongside clay votive tablets that became widely distributed throughout the region. Decorative arts flourished as well, with elaborate gold and silver objects and ceramics that reflect active trade connections with China. Eclectic in character, Srivijayan art absorbed elements from India, the Mon-Dvaravati sphere, Cambodia, and Java, creating a unique and influential regional style.

Architecturally, Srivijaya developed temples with cruciform or cross-shaped ground plans, typically featuring a central shrine surrounded by smaller subsidiary structures—an adaptation of Indian temple layouts. The kingdom also constructed stupas, the best-preserved example being the one at Wat Phra Borom Dhatu in Chaiya, Thailand, which retains original Srivijayan features. Most surviving architectural remains, such as those in Palembang, were built primarily of brick and are therefore less durable than the stone constructions of central Java. Important archaeological sites include Muara Jambi in Sumatra and Chaiya in southern Thailand.

Early Trade in Indonesia

Medieval Sumatra was known as the “Land of Gold.” The rulers were reportedly so rich they threw solid gold bar into a pool every night to show their wealth. Sumatra was a source of cloves, camphor, pepper, tortoiseshell, aloe wood, and sandalwood—some of which originated elsewhere. Arab mariners feared Sumatra because it was regarded as a home of cannibals. Sumatra is believed to be the site of Sinbad’s run in with cannibals.

Sumatra was the first region of Indonesia to have contact with the outside world. The Chinese came to Sumatra in the 6th century. Arab traders went there in the 9th century and Marco Polo stopped by in 1292 on his voyage from China to Persia. Initially Arab Muslims and Chinese dominated trade. When the center of power shifted to the port towns during the 16th century Indian and Malay Muslims dominated trade.

Traders from India, Arabia and Persia purchased Indonesian goods such as spices and Chinese goods. Early sultanates were called “harbor principalities.” Some became rich from controlling the trade of certain products or serving as way stations on trade routes. The Minangkabau, Acehnese and Batak— coastal people in Sumatra— dominated trade on the west coast of Sumatra. The Malays dominated trade in the Malacca Straits on the eastern side of Sumatra. Minangkabau culture was influenced by a series of 5th to 15th century Malay and Javanese kingdoms (the Melayu, Sri Vijaya, Majapahit and Malacca).

Zhao Rukuo, a Song Dynasty official and author of the 13th-century trade compendium Zhu Fan Zhi (Records of Foreign Peoples), described "Sanfoqi" (often identified as Srivijaya) as a powerful maritime kingdom in Southeast Asia, known for its vast trade, tribute to China, control of sea routes, rich products like camphor and ivory, and a significant Buddhist presence, though modern scholarship debates whether "Sanfoqi" always meant Srivijaya or sometimes Cambodia (Angkor). [Source: Google AI]

Srivijaya Trade and Economic Power

Srivijaya was the first major Indonesian commercial sea power. Primarily a costal empire, it drew its riches and power from maritime trade and extended its power to the coasts of West Java and Malaysia and to Vhaiya in southern Thailand. It was able to control much of the trade in Southeast Asia in part because its location on the Strait of Melaka between the empires of the Middle east, India and China. Merchants from Arabia, Persia and India brought goods to Sriwijaya’s coastal cities in exchange for goods from China and local products. [Sources: Library of Congress, noelbynature, southeastasianarchaeology.com, June 7, 2007]

At its zenith in the ninth and tenth centuries, Srivijaya extended its commercial sway from approximately the southern half of Sumatra and the Strait of Malacca to western Java and southern Kalimantan, and its influence as far away as locations on the Malay Peninsula, present-day southern Thailand, eastern Kalimantan, and southern Sulawesi. Its dominance probably arose out of policies of war and alliance applied, perhaps rather suddenly, by one local entity to a number of trading partners and competitors. The process is thought to have coincided with newly important direct sea trade with China in the sixth century, and by the second half of the seventh century Srivijaya had become a wealthy and culturally important Asian power.

expansion of the Srivijaya empire,

beginning in Palembang in the 7th century,

then extending to most of Sumatra,

then expanding to Java, the Malay Peninsula,

across Southeast Asia and Borneo

and ending as the Kingdom of Dharmasraya

in Jambi in the 13th century The important Strait of Melaka (Malacca) which facilitated trade between China and India. With its naval power, the empire managed to suppress piracy along the Malacca strait, making Srivjayan entrepots the port of choice for traders. Despite its apparent hegemony, the empire did not destroy the other non-Srivijayan competitors but used them as secondary sources of maritime trade. Srivijaya’s wide influence in the region was a mixture of diplomacy and conquest, but ultimately operated like a federation of port-city kingdoms. Besides the southern centre of power in Palembang, Arab, Chinese and Indian sources also imply that Srivijaya had a northern power centre, most probably Kataha, what is now known as Kedah on the western side of the Malay peninsula. Kedah is now known for remains of Indian architecture at the Bujang Valley. This was due to the invasion by the Chola kingdom from South India —“ an invasion which ultimately led to the fall of Srivijaya.

Dominating the Malacca and Sunda straits, Srivijaya controlled the trade of the region and remained a formidable sea power until the thirteenth century. Serving as an entrepôt for Chinese, Indonesian, and Indian markets, the port of Palembang, accessible from the coast by way of a river, accumulated great wealth. Control over the burgeoning commerce moving through the Strait of Malacca. This it accomplished by mobilizing the policing capabilities of small communities of seafaring “orang laut” (Malay for sea people), providing facilities and protection in exchange for reasonable tax rates on maritime traders, and maintaining favorable relations with inland peoples who were the source of food and many of the trade goods on which commerce of the day was built. But Srivijaya also promoted itself as a commanding cultural center in which ideas from all over Buddhist Asia circulated and were redistributed as far as away Vietnam, Tibet, and Japan. Srivijaya declined in the 11th century because of forced changes in trade routes brought about by increased piracy in the Sunda and Malacca Straits.

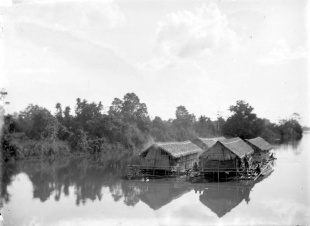

Palembang on the Musi River in Sumatra: Heart of ancient Srivijaya

In the latter half of the seventh century, the area around Palembang in southeastern Sumatra emerged as the center of the Srivijaya Empire. From this strategic base, Srivijaya controlled trade and shipping through the Strait of Melaka—one of Asia’s most important commercial corridors, used by regional powers and later by Europeans. Its command of maritime routes brought the empire immense wealth, enabling it to send trading missions as far as China and Sri Lanka. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Palembang, the second largest city in Sumatra today after Medan, was the celebrated seat of the Srivijaya kingdom for more than three centuries. The city was then known as the wealthy trade hub as well as the center for Buddhist learnings. Monks from China, India and Java used to congregate here to learn and teach the lessons of Buddha. In AD 671 the famous Chinese Buddhist monk, Yojing wrote that there were more than 1.000 Buddhist monks in the city and advised Chinese monks to study Sanskrit in Palembang before proceeding to India. While the Srivijaya kings lived inland on shore, his subjects lived along the wide Musi river, manning the powerful fleet and busily trading in gold, spices, silks, ivories and ceramics with foreign merchants who sailed in from China, India and Java. In 1025, however, the king of Chola in South India sent a fleet to Sumatra, destroying the kingdom, marking the end of its golden era. Later, Chinese admiral Cheng Ho, emissary of the Chinese emperor visited Palembang in the 15th century.

Palembang is also known in history as the origin of the Malays whose kings are believed to have descended to earth at Gunung Siguntang, north of Palembang.Today, not much can be seen from Srivijaya’s golden age, except for evidence of the area’s fine gold and silver songket weaving that persists until today, the fine lacquerware it produces for which Palembang is renowned, and its regal dances and opulent costumes.

On Kemaro Island in the middle of the Musi river there is a large Buddhist temple and the grave of a Chinese princess, who was destined to wed a Srivijaya king. The island is today the center of the Cap Go Meh celebrations. During Cap Go Meh, Chinese communities from around the city squeeze into this small piece of land, together with those coming from Hongkong, Singapore and China. Ever since the 9th century Srivijaya was a thriving trading power and an epicenter for Buddhist learnings, Chinese merchants came to trade in Palembang and monks stayed here to study Sanskrit before proceeding to India. Over the centuries many Chinese settled in the area.

Legend of the Srivijaya Princess and the Chinese Prince

There are many legends connected to the Chinese princess (or maybe a prince) buried on Kemaro. According to one version, the island is evidence and symbol of the love and loyalty of Princess Siti Fatimah, daughter of the King of Srivijaya, towards a Chinese prince called Tan Bun An. In the 14th century, so the legend goes, Prince Tan Bun An arrived in Palembang to study. After living here for some time, he fell in love with princess Siti Fatimah. He came to the palace to ask the king for her hand in marriage. The king and queen gave their approval on one condition, that Tan Bun An must present a gift.

Tan Bun An then sent a messenger back to China to ask his father for such a gift to be presented to the King of Srivijaya. When the messenger returned with pots of preserved vegetables and fruits, Tan Bun An was surprised and enraged because he had asked his father to send Chinese jars, ceramics and gold.In his anger he threw the ships cargo into the Musi River, unaware that his father had placed gold bars inside the fruits and vegetables. Ashamed after finding out his mistake, he tried to recover what he had thrown into the river. Tan Bun An, however, never returned as he drowned with the precious cargo.

When Siti Fatimah heard about the tragedy, the Princess ran to the river and drowned herself to follow her lover, but not before leaving a message saying; "If you see a tree grow on a piece of land where I drown, it will be the tree of our true love ".At the place where the princess drowned, a piece of land appeared on the surface of the river. The locals believe that this new island is the couple’s tomb and therefore, they call it "Kamarau Island" which means that despite high tides in the Musi River, this island will always remain dry.

The local ethnic Chinese believe that their ancestor, Tan Bun An, lives on this island. As a result, the island is always crowded during Chinese New Year. Today, a magnificent Chinese temple, the Hok Cing Bio, stands here. Built in 1962, it attracts many devotees. On special occasions, especially on what the Hokkien call the ‘Cap Go Meh’ Celebrations, the island is packed with locals and visitors coming from Palembang and overseas. There is something magical about Kamaro island. Witnessing the crowds on this particular occasion is an attraction by itself.

Srivijaya Civilization in Malaysia

In the 7th century the powerful Shrivijaya kingdom in Sumatra spread to Malay peninsula and introduced a mixture of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. Srivijaya influence extended over the Malay Peninsula and much of Borneo from the 7th to the 14th centuries. Shrivijaya ruled a string of principalities as far north Chaiya in what is today southern Thailand with support from China When Srivijaya in Chaiya extended its sphere of influence, those cities became tributary states of Srivijaya.

The Srivijaya kingdom in Malaysia was based in the the Bujang Valley or Lembah Bujang, a sprawling historical complex situated near Merbok, Kedah. It is regarded as the richest archaeological area in Malaysia. Over the years, numerous artefacts have been uncovered in the Bujang Valley — celadon, porcelain, stoneware, clay, pottery, fragments of glass, beads and Persian ceramics — evidences that Bujang Valley was once a centre of international and entrepot trade in the region.

More than 50 ancient Hindu or Buddhist temples, called candi, have also been unearthed, adding to the spirituality of the place. The most well-preserved of these is located in Pengkalan Bayang Merbok, which is also where the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum is located. This museum is the first archaeology museum built in Malaysia, under the Museum and Antiquity.

Kedah also had a strong Tamil influence which have led to surmise at least some of the Srivijaya maharajas may have been Tamiles. A 7th-century Sanskrit drama, Kaumudhimahotsva, refers to Kedah as Kataha-nagari. The Agnipurana also mentions a territory known as Anda-Kataha with one of its boundaries delineated by a peak, which scholars believe is Gunung Jerai. Stories from the Katasaritasagaram describe the elegance of life in Kataha. The Buddhist kingdom of Ligor took control of Kedah shortly after. Its king Chandrabhanu used it as a base to attack Sri Lanka in the 11th century, an event noted in a stone inscription in Nagapattinum in Tamil Nadu and in the Sri Lankan chronicles, Mahavamsa. [Source: Wikipedia]

Decline of Srivijaya Civilization in Malaysia

At times, the Khmer kingdom, the Siamese kingdom, and even Cholas kingdom in India tried to exert control over the smaller Malay states. In 1025 and 1026 Gangga Negara was attacked by Rajendra Chola I, the Tamil emperor who is now thought to have laid Kota Gelanggi to waste. Kedah—known as Kedaram, Cheh-Cha (according to I-Ching) or Kataha, in ancient Pallava or Sanskrit—was in the direct route of the invasions and was ruled by the Cholas from 1025. The senior Chola's successor, Vira Rajendra Chola, had to put down a Kedah rebellion to overthrow other invaders. The coming of the Chola reduced the majesty of Srivijaya, which had exerted influence over Kedah, Pattani and as far as Ligor. [Source: Wikipedia]

The power of Srivijaya declined from the 12th century as the relationship between the capital and its vassals broke down. Wars with the Javanese caused it to request assistance from China, and wars with Indian states are also suspected. In the 11th century CE the centre of power shifted to Melayu, a port possibly located further up the Sumatran coast at near the Jambi River. The power of the Buddhist Maharajas was further undermined by the spread of Islam. Areas which were converted to Islam early, such as Aceh, broke away from Srivijaya’s control. By the late 13th century, the Siamese kings of Sukhothai had brought most of Malaya under their rule. In the 14th century, the Hindu Java-based Majapahit empire came into possession of the peninsula.

By the fourteenth century, Srivijaya’s dominance had ended because it lost Chinese support and because it was continually in conflict with states seeking to dominate lucrative trade routes. In 1405 the Chinese admiral Cheng Ho arrived in Melaka with promises to the locals of protection from the Siamese encroaching from the north. With Chinese support, the power of Melaka extended to include most of the Malay Peninsula. Islam arrived in Melaka around this time and soon spread through Malaya.

As for the other region of Malaysia, Borneo, evidence suggests that Borneo developed quite separately from the peninsula and was little affected by cultural and political developments there. The kingdom of Brunei was Borneo’s most prominent political force and remained so until nineteenth-century British colonization.

Srivijaya Prince and the Founding of Malacca

The founding of trading port of Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula is credited to the Srivijayan prince Sri Paramesvara, who fled his kingdom to avoid domination by rulers of the Majapahit kingdom. In 1402 by Parameswara fled Temasek (now Singapore). The Sejarah Melayu claims that Parameswara was a descendant of Alexander the Great and said he sailed to Temasek to escape persecution. There he came under the protection of Temagi, a Malay chief from Patani who was appointed by the king of Siam as regent of Temasek. Within a few days, Parameswara killed Temagi and appointed himself regent. Some five years later he had to leave Temasek, due to threats from Siam. During this period, a Javanese fleet from Majapahit attacked Temasek. [Source: Wikipedia]

Parameswara headed north to found a new settlement. At Muar, Parameswara considered siting his new kingdom at either Biawak Busuk or at Kota Buruk. Finding that the Muar location was not suitable, he continued his journey northwards. Along the way, he reportedly visited Sening Ujong (former name of present-day Sungai Ujong) before reaching a fishing village at the mouth of the Bertam River (former name of the Melaka River), and founded what would become the Malacca Sultanate.

Over time this developed into modern-day Malacca Town. According to the Malay Annals, here Parameswara saw a mouse deer outwitting a dog resting under a Malacca tree. Taking this as a good omen, he decided to establish a kingdom called Malacca. He built and improved facilities for trade. The Malacca Sultanate is commonly considered the first independent state in the peninsula.

Srivijaya Civilization Thailand

The Wiang Sa Inscription (Thai Peninsula) dated 775 AD reads: “Victorious is the king of Srivijaya, whose Sri has its seat warmed by the rays emanating from neighbouring kings, and which was diligently created by Brahma, as if this God has in view only the duration of the famous Dharma.”

Joe Cummings wrote in the Lonely Planet guide for Thailand:While much of northern and eastern Thailand was controlled by the Angkor-based Khmers, “southern Thailand – the upper Malay Peninsula – was under the control of the Srivijaya empire, the headquarters of which is believed to have been located in Palembang, Sumatra, between the 8th and 13th centuries. The regional centre for Srivijaya was Chaiya, near modern Surat Thani. Remains of Srivijaya art can still be seen in Chaiya and its environs.” Srivijaya was a maritime empire that lasted for 500. It ruled a string of principalities in what is today Southern Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. [Source: Joe Cummings, Lonely Planet guide for Thailand]

Chaiya, near Present-day Surat Thani (685 kilometers south of Bangkok, jumping off area for Ko Samui), was a provincial capital of the Srivijaya Empire. Just north of Surat Thani city, Chaiya is the home of Wat Phra Boromathat, Thailand's most important monument from the Srivijaya period. Surrounded by walls and moats, this temple features a cloister with a large number of Buddhist images. At the center of the courtyard is an ancient Srivjaya-style stupa restored during the reign of King Rama V. Surat Thani is located on the Gulf of Thailand about equidistant between Bangkok and the Malaysian border.

When Srivijaya in Chaiya extended its sphere of influence, those cities became tributary states of Srivijaya. Srivijaya ruled a string of principalities in what is today southern Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Chaiya contains several ruins from Srivijaya times, and was probably a regional capital of the kingdom. Some Thai historians even claim that it was the capital of the kingdom itself for some time, but this is generally disputed. After Srivijaya lost its influence, Nakhon Si Thammarat became the dominant kingdom of the area. During the rule of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great of Sukhothai leader, Thai influence first reached Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south.

Fall of Srivijaya

By the early eleventh century, Srivijaya had been weakened by decades of warfare with Java and a devastating defeat in 1025 at the hands of the Chola, a Tamil (south Indian) maritime power. Chola launched an attack on Srivijaya, systematically plundering the Srivijayan ports along the Straits of Malacca, and even captured the Srivijayan king in Palembang. The reasons for this change in relations between Srivijaya and the Cholas are unknown, although it is theorised that plunder made up an essential part of the Chola political economy. While it seemed that the Cholas only intended to plunder Srivijaya, they left a lasting presence on Kataha, the remains of which are still visible at the Bujang Valley archaeological museum. [Source: noelbynature, southeastasianarchaeology.com, June 11, 2007]

The successful sack and plunder of Srivijaya had left it in a severely weakened state that marked the beginning of the end of Srivijaya. Having lost its wealth and prestige from the Chola attack, the port cities of the region started to initiate direct trade with China, shrugging off the exclusive influence Srivijaya once held over them. Towards the end of Srivijaya’s influence, the power centre of Srivijaya began to oscillate between Palembang and neighbouring Jambi, further fragmenting the once-great empire. Other factors included Javanese invasion westwards toward Sumatra in 1275, invading the Malayu kingdoms. Later towards the end of the 13th century, the Thai polities from the north came down the peninsula and conquered the last of the Srivijayan vassals.

Despite its influence and reach,Srivijaya flew very quickly into obscurity, and it was not until the last 90 years that the kingdom’s history was rediscovered, mainly through epigraphical sources. Palembang, determined as the centre of power for Srivijaya poses a special problem for archaeologists, for if the modern settlement followed the ancient settlement pattern, ancient Palembang would have been built over shallow water and any archaeological remains would be buried deep in the mud. As the 19th-century naturalist Alfred Wallace described it, Palembang is a populous city several miles long but only one house wide!

By way of a quick epilogue, the story of Srivijaya ends where the story of the Malacca Sultanate begins. The Sejarah Melayu, or Malay Annals, begins with a story about Raja Chulan —perhaps an allusion to the king (Raja) of the Cholas, whose sack of Srivijaya led to its ultimate downfall. The annals go on to relate the appearance of three princes at Bukit Seguntang in Palembang, one of whom eventually founds a city of Singapura in Temasek before establishing Malacca further north.

As Srivijaya’s hegemony ebbed, a tide of Javanese paramountcy rose on the strength of a series of eastern Java kingdoms beginning with that of Airlangga (r. 1010–42), with its “kraton” at Kahuripan, not far from present-day Surabaya, Jawa Timur Province. A number of smaller realms followed, the best-known of which are Kediri (mid-eleventh to early thirteenth centuries) and Singhasari (thirteenth century), with their centers on the upper reaches of the Brantas River, on the west and east of the slopes of Mount Kawi (Gunung Kawi), respectively. In this region, continued population growth, political and military rivalries, and economic expansion produced important changes in Javanese society. Taken together, these changes laid the groundwork for what has often been identified as Java’s—and Indonesia’s— “golden age” in the fourteenth century. In Kediri, for example, there developed a multilayered bureaucracy and a professional army. The ruler extended control over transportation and irrigation and cultivated the arts in order to enhance his own reputation and that of the court as a brilliant and unifying cultural hub. The Old Javanese literary tradition of the “kakawin” (long narrative poem) rapidly developed, moving away from the Sanskrit models of the previous era and producing many key works in the classical canon. Kediri’s military and economic influence spread to parts of Kalimantan and Sulawesi.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025