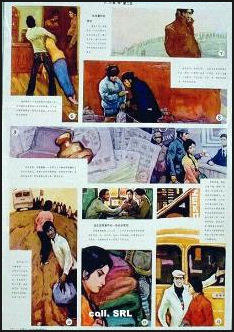

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN CHINA

Domestic violence remains a huge problem in China. According to Chinese government statistics released in January 2013, one in four women in China are subjected to domestic violence, including marital rape and beatings. Some experts say this figure is low because many never report it and it excludes sexual, psychological and emotional abuse.

Domestic violence remains a huge problem in China. According to Chinese government statistics released in January 2013, one in four women in China are subjected to domestic violence, including marital rape and beatings. Some experts say this figure is low because many never report it and it excludes sexual, psychological and emotional abuse.

The laws against domestic violence are weak and acceptance of the subjugation of women is deeply ingrained and goes back over two millennia. An old saying in China goes: "If you don’t beat up your wife every three days, she'll start tearing up the roof tiles" — meaning that a wife that is not periodically beaten gets out if control. The saying not only condones domestic violence but implies it is necessary. Laws against domestic violence have only recently been put on the books. In the early 2000, the marriage law was amended to explicitly outlaw domestic violence.

According to AFP: Less than two decades ago, physical abuse was not even acceptable as grounds for divorce in China. Nearly 40 percent of Chinese women who are married or in a relationship have experienced physical or sexual violence, the state-run China Daily newspaper reported, citing figures from the All-China Women’s Federation. The group, which is linked to the ruling Communist party, has reported that abuse takes place in nearly a quarter of Chinese families.“Domestic violence is illegal and affects family members physically and psychologically,” Tan Lin, head of the federation, told the China Daily. “It is not a private issue but a social problem.” [Source: AFP, November 26, 2014 **]

See Separate Articles:CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; TIGER MOTHER AMY CHUA factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN TRAFFICKING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

Victims of Domestic Violence in China

Cases of women being horribly disfigured with acid have been reported in China. In one village in Shaanxi province a woman was held down by three women while her husband poured acid on her face and breast, scaring her horribly for he rest of her life. Her crime: she tried to leave her husband, who repeatedly beat her, and sought a divorce. Husband abuse is also a serious problem. Incidents of men being bullied and beaten by viscous wives are frequently reported. A Chinese sociologist told the International Herald Tribune that husbands are “easy prey to their wives who either complain about money and household chores or try to beat their husbands into acceptance of extramarital affairs.”

NPR reported: “ Kim Lee, a victim of abuse in a highly publicized case (See Below) said she received messages from more than 1,000 women. "They range from absolutely heart-wrenching — from a teenager, 'My mom killed herself to punish my dad... she couldn't do anything. "And sometimes women will send me photos, and they're horrible. And they'll say, 'Kim, please delete this after I send it to you. My husband will kill me if he knows I told anyone, but I can't tell anyone, and what should I do?' [Source: NPR, February 7, 2013]

Though domestic violence is illegal in China, many still consider it a private matter in which the state has no business interfering. Ying Zhu wrote in China File, In 2009,Zhang Yue, the host of a women’s program on China Central Television (CCTV) called Half the Sky, “recounted how a series of gender-consciousness training sessions helped to inject progressive gender politics in the program’s otherwise-resistant production crew. She told me how, during one intense discussion, a male colleague broke down, tearfully confessing that he beat his wife. He lived in a small town in northern China where men routinely beat their wives, Zhang recalled. “He was much ashamed about the belated awareness of domestic abuse and later apologized to his wife. But many men still consider wife-beating an honorable thing to do,” she said. “I was in northeast China the other day, and a group of men confronted me, telling me that our program was misguided and that there was nothing wrong with beating up one’s wife because how else can one turn a woman into a good wife.” [Source: Ying Zhu, China File, February 11, 2013]

Wife Beating in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “The beating of Chinese wives by their husbands is regarded as a matter of course. One of the first questions which is asked of foreign ladies, by the Chinese women with whom they become well acquainted, is, " Does he not beat you?" The replies are generally received with incredulity! On one occasion when these enquires had been made and answered as usual, none of the Chinese women present could boast of not having been beaten, except the old grandmother who was more than eighty years of age. Her recipe was of the simplest description, but for a Chinese woman most difficult, to wit to hold her tongue. There are probably very few Chinese women to whom this method ever occurred, or who would be capable of adopting it if it had occurred to them. "When you are young, and just married," said the old lady, " your husband does not like to beat you. When you get older and have a troop of children, if he beats you they all come out shrieking and making such a clamour that he dislikes to face it. And when you are old, he does not care to begin for the first time, and there you are, never having been beaten all your life! " [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

“Unfortunately this sound domestic philosophy is for the most part theoretical. Knowing that one of the sons of this old lady had a wife who was a thorn in the flesh, the writer once enquired a little into their matrimonial relations, and ascertained what was indeed a matter of general notoriety among the inhabitants of. the large town in which she lived, that these relations were at times what the diplomatists term " strained." The husband was a man of some education, less than forty years of age, his wife a woman rather taller than himself, and not unpleasing in appearance. There was never anything in their demeanour to indicate that they were in any respects different from any of their neighbours, as indeed they were not. This semi-literary man informed us that he had beaten his wife times without number. Sometimes he had used a club two feet long and an inch or two in thickness, made of a particularly hard wood. Sometimes he had used an ashscraper, which happened to be the most convenient weapon. Once he beat her until his arm was tired, and he was all of a tremble. During all this time, she was shrieking, "Mother, Mother!" but the moment he stopped, she began reviling him, on which he resumed the beating, and she resumed her invocations to her "Niang." On one of these occasions she had been pregnant, for four or five months. Two days after, she jumped into a deep well, but was hauled out by a rope. The child lived, strange to say, but was smothered at the age of one month, by being lain upon. On another occasion she hung herself with her girdle, which broke, leaving her in a heap on the ground from which she refused to rise. At another time she ate two handfuls of a poisonous rouge-powder, but nothing came of it! Another Chinese woman known to the writer, felt deeply humiliated at having been beaten by her husband. Being urged to forgive him, she at last consented, but declared that she would never be buried in the same grave yard with him — never!

“M. Hue tells a story, which to many of his readers must have seemed an idle tale, of a Chinese husband who had a wife with whom he had lived happily for two years. But having conceived the idea that people were laughing at him, because he had never beaten his wife, he determined to make a beginning in such a way as to impress every spectator, and accordingly, though he had no fault to find with her, he beat his wife to such an extent that she could neither move nor speak, and although her husband was kind enough to admit that he was in error, she died two days afterwards in terrible convulsions. In the chapter on the absence of sympathy, reference was made to the daughter of a woman employed as a nurse in a foreign family, the husband of which daughter had abused her severely. Within the short time since that account was written, this young woman has again fallen into deep trouble. Her husband came into the house one day when she was engaged in some domestic occupation and without any anger in his manner told her to take off her clothes. She dared not refuse, and he then cruelly beat her with a thorny stick, till the blood ran. She was more terrified by this experience than by all that had gone before, on account of the deliberate malice, and the absence of any cause. A man who will beat his wife till she streams with blood, while he is a careful not to injure her garments with the thorns, is not unlikely to beat her because he dreads the ridicule of the neighbours.

“Within the past few days word has been brought to the writer that the wife of a younger brother of a man living on the premises has swallowed opium, and thus committed .suicide. Why did she do so? Because her husband beat her. And why did her husband beat her? Because she had irritated the neighbours over the wall by reviling them. And why did 'she revile her neighbours? Because they had her property in their charge, and she took it for granted that they would not give it up, and revenged herself in advance by reviling them. To be more explicit; the eggs laid by domestic fowls are often considered by the women of the family as their perquisites. In this instance a hen had flown over the neighbours' wall, and had been heard to cackle, implying that the egg had been laid over there. No one appears to have even contemplated the possibility that the egg could be regained. The woman accordingly reviled the neighbours, with consequences already described. The value of the egg, at current rates, was three cash. About the same time that this happened, a case occurred in a city more than a thousand miles distant, in which a Chinese killed another in a dispute which involved only one cash!

Crazy English Teacher Admits to Domestic Violence

"Crazy English," a method of learning English that involves shouting out English words at the top of one's lungs, was very popular in the 2000s. Its founder, Xinjiang-born and Beijing-based Li Yang, is paid $20,000 a year by rich parents to teach their kids. Sometimes 40,000 paying customers show up to see him at stadium appearances.

Evan Osnos wrote on The New Yorker website, In September 2011 "Li's wife publicly posted photos of her herself online with severe bruises on her head and knees and, in a series of Twitter-like messages, she vowed to seek a divorce. (She wrote, “You knocked me to the floor. You sat on my back. You choked my neck with both hands and slammed my head into the floor. When I pried your hands from my neck you grabbed my hair and slammed my head into the floor ten more times!”)

In China, it was a sensation, drawing headlines and thousands of online comments; people condemned the Crazy English founder and demanded that he respond. For days Li stayed silent, but later he admitted to “domestic violence” against his wife and kids that “caused them serious physical and mental damage.” In a strange interview with China Daily...he sounded less than contrite, saying the “problem involves character and cultural differences, which are difficult to solve through counseling.” According to the article, he also said, “I hit her sometimes but I never thought she would make it public since it’s not Chinese tradition to expose family conflicts to outsiders. But I still respect her for raising three girls on her own and for her passion for her students.”

If there is anything positive to be sifted from the sad affair, it is that the case has focused attention to China’s under-discussed problems of domestic violence, especially in high-income urban families. When it is discussed, abuse is usually described as a problem left over in remote rural areas, but Li’s case has prompted Chinese counselors to report that “nearly half of domestic violence abusers are people who have higher education, senior jobs and social status.”

Crazy English Wife Abuse Spotlights Domestic Violence in China

In February 2013, NPR reported: “The faces of American Kim Lee and her Chinese husband, Li Yang, both in their 40s, once graced the covers of books that sold in the millions. He was China's most famous English teacher, the "Crazy English" guru of China, who pioneered his own style of English teaching: pedagogy through shouted language, yelling to halls of thousands of students. His methods were given official recognition after he was employed by the Beijing Olympic Organizing Committee . A fellow teacher, Lee married Li in 2006. They have three daughters. And Lee, who is from Florida, worked alongside her husband to build the Crazy English empire. "I enjoy losing face!" is one of Li's mottoes, in a bid to lessen the inhibitions of China's shy language learners, who fear mistakes. But 18 months ago, his wife used that slogan against him. [Source: NPR, February 7, 2013 ^^]

“When he brutally beat Lee, she posted a picture of her battered face, showing a huge lump protruding from her forehead. She put it on his page on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, under the heading, "I love losing my face = I love hitting my wife's face?" She followed this with pictures showing her bloodied ear and raw, injured spots on her knee. "Li Yang, you need help," she wrote. "Domestic violence is a serious problem." ^^

“She says she went public out of desperation, trying to get her husband's attention. "That day the violence was so horrific. I went to the police station, and I went to the hospital, and my husband went on TV and did a TV show. I thought maybe he just didn't even realize how seriously he hurt me, even though he was sitting on my back, slamming my head in the floor," Lee recalls. "I thought, that will really get his attention. Maybe then he'll come to the realization, 'Oh, I've really seriously injured my wife. I better go home, I better deal with this.' But he didn't." ^^

“As her photos went viral, the story spiraled into the public consciousness, marking the first time a high-profile wife in China had publicly announced that she'd been beaten. "I hit her sometimes, but I never thought she would make it public since it's not Chinese tradition to expose family conflicts to outsiders," . He blamed their problems on "character and cultural differences, which are difficult to solve through counseling."But in other interviews, he gave literal blow-by-blow accounts. He even told one journalist he'd only married Lee as a cultural experiment, for research in American child-rearing techniques.” ^^

Ying Zhu wrote in China File, “Lee endured years of an increasingly loveless and volatile relationship—during which Li spent most of the time away from Lee and their three daughters, visiting home only two days most months.... While living with Li in Beijing, Lee had no bank account, no property under her name, not even a driver’s license. She relied solely on the cash Li delivered to her in an envelope each month... Li was unperturbed by her wounds, rebuffing Lee in public for defying Chinese tradition by taking a domestic matter public. [Source: Ying Zhu, China File, February 11, 2013]

Reaction to the Crazy English Wife Abuse Case

Ying Zhu wrote in China File, “The case aroused strong reactions among China’s Netizens. While many women wrote to relay their own sufferings at the hands of men or to express sympathy and show support, some questioned whether Lee was making too big a fuss over what they took as routine. Indeed for many in China, especially in rural areas, physical violence within the confines of the family is an accepted part of a marital relationship where wife-beating is a man’s natural right. [Source: Ying Zhu, China File, February 11, 2013]

Zhang Yue, the host of a women’s program on China Central Television (CCTV) called Half the Sky, She interviewed Li Yang in 2009 when rumors surfaced that he had hit his wife. But Zhang softballed the interview and later was criticized online by regular Netizens for taking lightly the pride of a battered woman, and an American, no less. On September 25, 2011 shortly after Kim Lee took her case public, another CCTV program, the weekly news magazine show Eyewitness, persuaded Lee and her husband Li Yang to appear on the program, albeit separately, to talk about marriage and domestic relations. The interviewer, Chai Jing, an empathetic young woman, was incredulous when confronted with Li’s utter lack of emotion.

“At one point, Li said that he was kind enough to grace his home with his presence once or twice a month. “I did not have to go home at all,” he said matter-of-factly. The contrast between Lee’s devastation and pleading and Li’s chilly lack of emotional response or genuine remorse was shocking. Footage of Li’s female fans reassuring him that he had done no wrong and that his wife had blown things out of proportion was jarring to say the least. Yet this is the reality of China.

Crazy English Wife Abuse Court Case and Investigation

NPR reported: “ Their 18-month legal battle was to become the country's most closely watched divorce case. When the verdict finally came on Feb. 3, it made the nightly news. A Beijing court ruled in Kim Lee's favor, granting her a divorce, custody of their three children, compensation of $8,000 for the abuse and assets of almost $2 million. The court issued a restraining order against her ex-husband — the first time ever in Beijing. [Source: NPR, February 7, 2013 ^^]

“For Lee, it's been a long struggle against an unsympathetic police system. She describes hours of endless waiting and countless examples of official obfuscation. In one instance, she was told her physical evidence was inadmissible because she had visited the wrong hospital. Another time she was told that the correct police official was not present to take her evidence. And she was also informed that voice recordings were needed of her husband's threats against her. "The whole system here is designed to pressure women to give up and just drop it. But I didn't. I just didn't give up," Lee says. "So that's why when they read the decree and they issued the protection order, I just really sighed. I think I earned it." ^^

"I made a conscious decision. I used a Chinese lawyer, I used Chinese courts," she says. "To be honest, a lot of my American friends did not understand this. They were like, 'You're crazy. You're American. Go to the embassy immediately.' But I did not want to teach my daughters, 'No one can beat you because you're American.' I wanted to teach them, 'No one can beat you because you're a person, you're a woman.' " Feng Yuan, a women's rights activist, says the case is extremely important. "It's a milestone case in China against domestic violence against women," Feng says. "Her admission she'd been abused allowed it to become a topic of public discussion because of media concern. It also highlights the deficiencies in current Chinese law, and what needs to be changed to better protect women." ^^

Later Xinhua reported: “Chinese "Crazy English" teacher Li Yang has filed an appeal to a Beijing court over the divorce granted to his former wife, disagreeing with the domestic abuse charge and compensation order. According to the Beijing Chaoyang District Court verdict, Li was ordered to pay his former wife 50,000 yuan (about $7,960 dollars) in compensation for her psychological traumas and a one-off sum of 12 million yuan in consideration of the property the couple shared, in addition to an annual child support payment of 100,000 yuan to each of their three daughters before each turns 18. In his appeal, Li disagreed with the property distribution and compensation, claiming he himself was also the victim of domestic violence in the relationship. [Source: Xinhua, February 20, 2013]

Abuse Laws in China

According to article 260 of the PRC Criminal Law, abusing a family member is punishable by imprisonment for up to two years, criminal detention, or public surveillance, when the circumstances are serious. Abusing a family member causing serious injury or death to the victim is punishable by imprisonment for no less than two years and up to seven years. [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2019 |*|]

For the crime of abuse, article 260 previously provided that this offense was “to be handled only upon complaint.” The Ninth Amendment of the Criminal Law adds to this provision that the offense was to be handled upon complaint “unless the victim is not capable of or unable to bring a complaint due to coercion or intimidation.” The previous provision created an obstacle for children and other vulnerable victims seeking redress. With such an amendment, it is now possible for perpetrators of abuse against children to be prosecuted without the victim filing a complaint.

In addition, the Ninth Amendment adds a sub-article as article 260a, which extends the scope of application of the crime of abuse to caregivers and legal guardians in institutions and other facilities. Under the new article 260a, any person who is responsible for the guardianship or care of minors, the elderly, persons with illness, or persons with disabilities is punishable by imprisonment for up to three years or criminal detention for abusing such persons. |*|

The Chinese government passed a first-of-its-kind anti-domestic-violence bill in 2015. The law was welcomed by advocates as a step in the right direction. It includes provisions such as restraining orders. Since 2000, local governments across China had passed local regulations on domestic violence. But these regulations focus on general principles and lack specific provisions to effectively protect women from domestic violence. In Sichuan Province the anti-domestic violence regulation does not include protective orders for victims.

The drafting of anti-domestic violence legislation was prompted the Supreme People’s Court’s own investigation into the issue. The investigation, made public in January 2013, found that laws and regulations at that time were insufficient to protect women from domestic violence. According to the Supreme People’s Court then, there was no clear standard stipulating the conditions under which investigations and prosecutions should be initiated; as a result, such investigations and prosecutions were rare, which is still true now. Even when such cases do come before courts, judges tend to treat domestic violence as a marital dispute and issue light punishments to abusers. The Supreme People’s Court investigation also pointed out that in cases where women respond to violence with violence, law enforcement agencies tend to discount their claims of abuse and failed to take them into account during sentencing. [Source: Human Rights Watch, January 30, 2013]

Drafting of China's Anti-Domestic Violence Law in 2014

In November 2014, China drafted its first national law against domestic violence. Activists hailing it as a step forward in a country where abuse has long been sidelined as a private matter but criticized it for being too watered down. AFP reported: “The new law formally defines domestic violence for the first time and streamlines the process for obtaining restraining orders – measures long advocated by anti-domestic abuse groups. “Over the years, we’ve many times felt powerless ourselves to help victims,” said Hou Zhiming, a veteran women’s rights advocate who heads the Maple Women’s Psychological Counselling Centre in Beijing. “If this law is actually enacted – because the issuing of a draft means it will now enter the law-making process – we will be very pleased....At the very least, there’s finally movement on this law.” [Source: AFP, November 26, 2014 **]

“But advocates also say the draft law, released by the Legislative Affairs Office of China’s State Council, excludes unmarried and divorced couples and falls short in some other areas. Julia Broussard, country programme manager for UN Women, said that UN agencies were thrilled to see the law made public after more than a decade of efforts by Chinese advocates, “but we did note right away that it doesn’t extend to any non-family relations”. “We know that domestic violence is also occurring in the context of other relationships not defined as family relationships,” including dating, cohabiting and same-sex couples, Broussard said. “And so, our concern is that some of the violence is not going to be addressed by the law,” she added. **

“But without a legal definition of the term, many victims – if they report abuse at all – have been shuffled from police to women’s federation to neighbourhood committee, with authorities reluctant to intervene unless serious injury is involved. “It’s very important for China to have some kind of nationwide, targeted domestic violence legislation on the books, because it has not had it, and it’s been a real legal barrier for a lot of women seeking to extricate themselves from very abusive relationships,” said Leta Hong Fincher, author of Leftover Women: the Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China. Despite the shortcomings, we need to acknowledge that this is important legislation and a very important first step towards tackling this epidemic of domestic violence in China,” she said. **

“Currently, little protection is available if a partner threatens violence against a victim who tries to leave, activists note, as restraining orders are rarely issued in China and shelters are nearly non-existent. Courts must rule on restraining order requests within 48 hours, according to the draft law – but if one is granted, the victim must start a lawsuit within 30 days or it would lapse. Experts say it is rare for domestic violence laws to require victims to undertake a lawsuit to obtain or maintain a restraining order. “This is a bit problematic,” Broussard said. “We know from experience that many victims are not necessarily at that point of seeking divorce or some other kind of legal action that would be required to maintain the legal protection ruling.” **

Death Sentence Given to Victim of Severe Domestic Violence in China

In January 2013, Li Yan was given the the death sentence after being convicted of killing her husband following months of violent abuse that included hacking off one of her fingers. She went to the police, but they didn't intervene. According to Human Rights Watch: In November 2010, Li Yan, from Sichuan Province, killed her husband Tan Yong following a violent dispute. According to Li’s lawyer, Tan had kicked Li and threatened to shoot her with an air rifle when Li grabbed the rifle and struck Tan with it, killing him. Li then dismembered Tan’s body. “It is cruel and perverse for the government to impose the death penalty on Li Yan when it took no action to investigate her husband’s abuse or to protect her from it,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “China’s legal system needs to take account of the circumstances that can lead domestic violence survivors to resort to violence in self-defense.” [Source: Human Rights Watch, January 30, 2013]

Li and Tan had married in March 2009 and Tan started to abuse her soon after. According to Li’s lawyers and her brother, Tan had abused Li in the months prior to the murder: he had kicked and beaten her, locked her in their home during the day without food or drink, locked her out overnight on the balcony including during winter, burned her face and legs with cigarette butts, and once dragged her down three flights of stairs by her hair. Li had repeatedly complained about Tan’s abuses to the police, to the neighborhood committee, and to the local branch of the government-organized All China Women’s Federation (ACWF) as early as August 2010. Evidence of that abuse, including police records, hospital records, witness testimony, pictures of her injuries, and complaints to the ACWF, were presented in court. Neither the police nor the ACWF investigated the allegations against Tan. According to Li’s brother, the police had told Li that this was a “family matter” and that she should seek help from the local neighborhood committee.

However, the Ziyang City Intermediate People’s Court ruled that the evidence was insufficient to confirm that Li suffered domestic violence. Because all the witness statements affirming Li’s injuries had come from her friends and family, and because the authorities to whom Li had reported the abuse had taken no action to investigate and confirm Tan was the source of the abuse, the court ruled that it was not clear that domestic violence had taken place. The court convicted her of “intentional homicide” and stated that the death penalty is warranted because “the murder was committed in a cruel fashion and that the consequences severe.”

An appeals court upheld this decision in August 2012. Li’s case was then transferred to the Supreme People’s Court, which reportedly approved the execution recently but has not yet issued the execution order, according to lawyers familiar with the case. Once the order is issued, Li will be executed within seven days.Since her case and sentence have become known to the public in recent weeks, nearly 400 Chinese citizens, lawyers, and scholars have signed petitions calling for a halt of the execution. Separately, since November 7, more than 8,000 people have signed another petition calling for anti-domestic violence legislation.

Domestic Violence Murder Trial in China

Reporting from Luyi County in Henan Province, Emily Rauhala wrote in the Washington Post: In a courtroom in the Chinese heartland, a defense attorney made his final pitch. That his client, Zhang Yazhou, killed his wife was not in question. At 5:25 in the evening on Feb. 21, Zhang walked into his wife’s hospital room. They argued. He strangled her, digging his fingers deep into the flesh of her neck. By the time nurses entered the room, Zhang was gone and Li Hongxia, just 24, was dead. Since Zhang confessed on television and in court, the issue at hand was the sentence. Li’s family and their lawyer asked for the death penalty, which is common in China, describing a year of escalating abuse that culminated in a brutal murder. “The defense asked for leniency on the grounds that Zhang had admitted his guilt and that Li’s death was different than “regular” acts of violence — because she was Zhang’s wife. In the end, the court in Henan province took a relatively tough line, sentencing Zhang to death with a two-year reprieve — meaning he could get life, or a shorter, fixed-term sentence if he behaves in jail — consistent with Chinese law, lawyers said. [Source: Emily Rauhala, Washington Post, August 27, 2016]

“Yet the court’s written judgement says plainly that Zhang’s penalty was indeed reduced because it was a domestic case. Zhang got a reprieve, not immediate execution, because the case was “caused by family conflict and the defendant Zhang Yazhou turned himself in,” the judges wrote. Asked about Li’s death, the head of the Federation’s Luyi County office, Guo Yanfang, blamed Li for not reporting her husband, but also said she advises abused women to work things out with their spouses. If a man is “not going to kill you or harm you, if he is good in nature but just being young and impulsive,” a woman should try to win him back “to save the family,” she said. “Isn’t every family like this?” she said. “There is always smoke coming from the kitchen stove.”

“In Luyi County, the legal system as a whole seemed to see domestic violence as both normal and inevitable. In statements to the court, the defendant, Zhang, and lawyer Cui Xiaolin played up the fact that the couple fought before the murder, presenting Li’s death by strangulation as distinct from other more cold-blooded crimes. “It was a crime of passion; the two had a dispute and then this thing happened,” Cui said after the trial. Zhang, the confessed wife-beater and murderer, was not a particularly “malicious” man, he added. Cui argued that Zhang should be spared the harshest sentence because the couple had a 2-year-old daughter who needed him. “She already lost her mom, she can’t lose her dad,” he told the court.

“Chinese lawyers who work closely with survivors of domestic violence said the case sent a mixed message. On one hand, the punishment was not light — a sign, they hoped, that judges will take violence seriously, even violence against a wife. On the other, many involved showed a limited understanding of the ideas outlined in the anti-domestic-violence law. Lu Xiaoquan, a Beijing-based lawyer who specializes in domestic violence but was not involved in Li’s case, said the level of knowledge about intimate-partner violence in China remains “pathetic.”

Li’s family worried that the murder of a poor woman in rural China would be swept away like dust, making it easy for the next abuser to strike. They wanted her death to change that — she deserved as much. Although the family is glad Zhang will do time, they are outraged and demoralized by the legal process as a whole, said Li’s older sister, Yan Jinjin, after they received a copy of the judgment. “We don’t think my sister got the justice she deserved,” she said. In fact, Li’s family was so certain her death would be brushed aside that, after her murder, they refused to bury her body, keeping her corpse aboveground in a desperate bid to shame the state to act.

Problems with China’s Laws and Attitudes Towards Domestic Violence

Emily Rauhala wrote in the Washington Post: Li’s killing showed the limits of using the law alone to keep women alive. In the last year of her life, Li knew she needed to leave her husband but was told by those around her — family and friends, neighbors and nurses — to go quietly back to Zhang. “Chinese law enforcement has taken a cavalier approach to investigating violence against women. [Source: Emily Rauhala, Washington Post, August 27, 2016]

In 2011, Kim Lee, from the Crazy English case described above, went public with an account of the beatings and the indifference of local police. In a 2014 essay, Kim recalled going to the police station after an attack, only to be told to go home and sort it out. “As far as the police were concerned,” she wrote, “no crime had occurred.” The Federation campaigned hard for the anti-domestic-violence bill, but also encourages women to get and stay married — even, in some cases, when there is evidence of abuse.

“The state’s effort to stop domestic violence is undermined by the persistent belief that domestic abuse is somehow a lesser form of violence, that it is not as serious as “regular” crimes. In the months since Li’s murder, local officials have repeatedly shirked responsibility for her death, dodging questions, blaming Li and playing down her husband’s culpability. The head of Li’s village, an official named Li Jie, called the dead woman “cowardly” for failing to report previous beatings. She could and should have saved herself by “saying no to domestic violence,” he said after her death. She should have reported abuse to the village council or the All-China Women’s Federation, a Communist Party-backed body, he added. “Both could have helped her protect her rights and interests.”

“Yet there is little evidence that the council, the Federation, or other state-linked bodies would have helped her leave safely. “A law, no matter how good it is, is only a piece of blank paper without implementation,” he said. “If the law cannot be effectively implemented, similar cases will appear.” That’s exactly what Li’s family feared.

Image Sources: Posters: Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); China.org, the Chinese government news site, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2021