OPIUM WARS PERIOD IN CHINA

In 1839, Lin Tse-Hsu, the imperial Chinese commissioner in charge of suppressing the opium traffic in China, ordered all foreign traders to surrender their opium. In response, the British sent a group of warships to the coast of China, triggering the First Opium War, which the British won in 1841. Along with paying a large indemnity, the defeated Chinese ceded Hong Kong to the British. In 1856, hostilities towards China were renewed, this time by the British and French, resulting in the Second Opium War, which China again lost. After this China was forced to pay more indemnity and the importation of opium to China was legalized.

In 1839, Lin Tse-Hsu, the imperial Chinese commissioner in charge of suppressing the opium traffic in China, ordered all foreign traders to surrender their opium. In response, the British sent a group of warships to the coast of China, triggering the First Opium War, which the British won in 1841. Along with paying a large indemnity, the defeated Chinese ceded Hong Kong to the British. In 1856, hostilities towards China were renewed, this time by the British and French, resulting in the Second Opium War, which China again lost. After this China was forced to pay more indemnity and the importation of opium to China was legalized.

The success of the Qing dynasty in maintaining the old order proved a liability when the empire was confronted with growing challenges from seafaring Western powers. The centuries of peace and self-satisfaction dating back to Ming times had encouraged little change in the attitudes of the ruling elite. The imperial Neo-Confucian scholars accepted as axiomatic the cultural superiority of Chinese civilization and the position of the empire at the hub of their perceived world. To question this assumption, to suggest innovation, or to promote the adoption of foreign ideas was viewed as tantamount to heresy. Imperial purges dealt severely with those who deviated from orthodoxy.[Source: The Library of Congress]

When the Qianlong Emperor died at last in February 1799, leaving the kingdom apparently prosperous, but in fact riddled with contradictions and problems that had never been properly solved. China in the 19th century was humiliated and emasculated by colonialism after the Opium Wars, torn apart by rebellions and brought to its knees by famines. Most of the decisive events in 19th century occurred in southern China. The First Opium War (1839-42) took place primarily around Hong Kong and Canton. Shanghai was the center of the foreign occupation. And, the Taiping Rebellion (1851 to 1864) transformed parts of southern China into a brief quasi-utopian state.

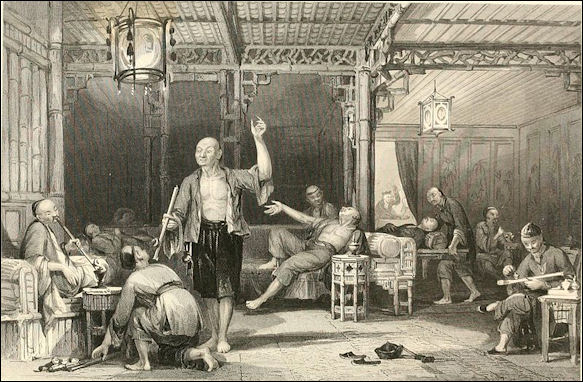

barbers in a clearing

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “At the time these events were perceived [in China] largely as a border skirmish. The Qing emperor was preoccupied with a series of internal rebellions, and his officials were so nervous of passing on the letters the British handed in that he had little idea of what the trouble was about. When hostilities began, repeated accounts of glorious Chinese victories over the barbarians left the emperor in the dark about the real outcome. It was an inglorious episode on both sides, with its roots in an expanding imperial power being rebuffed in its efforts to trade.” [Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, September 11, 2011]

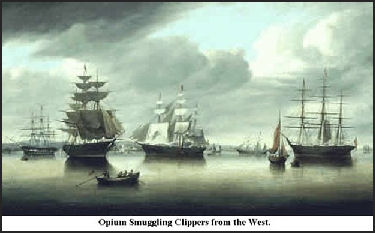

“There was nothing, the Chinese loftily replied to the British emissaries, that China needed or wanted from the west not their goods, not their ideas and certainly not their company. There was plenty that the British wanted to buy from China, though, and by the 1780s, the British appetite for tea and Chinese indifference to British goods had produced a trade deficit that the East India Company began to fill by supplying opium grown in British Bengal. It was a trade that greatly benefited the British exchequer, the merchants who traded it, the officials who grafted on it, the Chinese wholesalers who bought it and the foreign missionaries who travelled with it.”

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu; Opium Wars : Emperor of China’s War on Drugs Opioids.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinese History: Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; OPIUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com : OPIUM WARS AND THEIR LEGACY factsanddetails.com; FOREIGNERS AND CHINESE IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF CHINESE AMERICANS AND IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com ; TAIPING REBELLION factsanddetails.com; SINO-JAPANESE WAR factsanddetails.com; BOXER REBELLION factsanddetails.com; EMPRESS DOWAGER CIXI, HER LOVERS AND ATTEMPTED REFORMS factsanddetails.com; PUYI: THE LAST EMPEROR OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China" by Julia Lovell (Picador, 2011) Amazon.com; “Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age”by Stephen R. Platt, Mark Deakins, et al. Amazon.com; "Opium Regimes, China, Britain and Japan, 1839-1952" edited by Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi Amazon.com; "Sea of Poppies" by Amitva Ghosh (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008) a novel set during the Opium Wars mostly in India but also in China Amazon.com; “The Qing Empire and the Opium War: The Collapse of the Heavenly Dynasty” by Haijian Mao, Joseph Lawson Amazon.com; “The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700–1845" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke “Whampoa and the Canton Trade: Life and Death in a Chinese Port, 1700–1842" by Paul A. Van Dyke Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 11: Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911, Part 2" by John K. Fairbank and Kwang-Ching Liu Amazon.com; Amazon.com;

China in the Early 19th Century

“By the nineteenth century, China was experiencing growing internal pressures of economic origin. By the start of the century, there were over 300 million Chinese, but there was no industry or trade of sufficient scope to absorb the surplus labor. Moreover, the scarcity of land led to widespread rural discontent and a breakdown in law and order. The weakening through corruption of the bureaucratic and military systems and mounting urban pauperism also contributed to these disturbances. Localized revolts erupted in various parts of the empire in the early nineteenth century. Secret societies, such as the White Lotus sect in the north and the Triad Society in the south, gained ground, combining anti-Manchu subversion with banditry. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Qianlong Emperor receiving Lord McCartney

The Manchus were sensitive to the need for security along the northern land frontier and therefore were prepared to be realistic in dealing with Russia. The Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) with the Russians, drafted to bring to an end a series of border incidents and to establish a border between Siberia and Manchuria (northeast China) along the Heilong Jiang (Amur River), was China's first bilateral agreement with a European power. In 1727 the Treaty of Kiakhta delimited the remainder of the eastern portion of the SinoRussian border. Western diplomatic efforts to expand trade on equal terms were rebuffed, the official Chinese assumption being that the empire was not in need of foreign — and thus inferior — products. Despite this attitude, trade flourished, even though after 1760 all foreign trade was confined to Guangzhou, where the foreign traders had to limit their dealings to a dozen officially licensed Chinese merchant firms.

Trade was not the sole basis of contact with the West. Since the thirteenth century, Roman Catholic missionaries had been attempting to establish their church in China. Although by 1800 only a few hundred thousand Chinese had been converted, the missionaries — mostly Jesuits — contributed greatly to Chinese knowledge in such fields as cannon casting, calendar making, geography, mathematics, cartography, music, art, and architecture. The Jesuits were especially adept at fitting Christianity into a Chinese framework and were condemned by a papal decision in 1704 for having tolerated the continuance of Confucian ancestor rites among Christian converts. The papal decision quickly weakened the Christian movement, which it proscribed as heterodox and disloyal.

Chinese View of Foreign Incursions on Chinese Soil

According to the Chinese government: In 1644 the Qing troops marched south of Shanhaiguan Pass and unified the whole of China, initiating nearly 300 years of Manchu rule throughout the country. The Manchus made their contributions in defending China's frontiers from foreign aggression. As early as the mid-17th century, Russia made repeated incursions into areas along the Heilong River. In 1685, on orders of Qing Emperor Kang Xi, Manchu General Peng Chun led his "eight banner" troops and naval units in driving out the Russian invaders. The subsequent Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed on an equal footing in 1689, delineated a boundary line between China and Russia, and maintained normal relations between the two countries for more than 100 years. [Source: China.org china.org |]

“Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, troops sent by the Qing court repulsed British-backed Gurkha invasions of southern Tibet and local rebellions in Xinjiang, also incited by the British colonialists. These and other military exploits of the Manchu emperors brought into being a unified Chinese state that extended from the outer Hinggan Mountains in the north to the Xisha Islands in the south, and from the Pamirs in the west to the Kurile Islands in the east in the heyday of the Qing Dynasty. |

“China was reduced to the status of a semi-colonial and semi-feudal country after the Opium War of 1840. During the war, many Manchus, as well as Hans, lost their lives in fighting for China's independence and the dignity of the Chinese nation. A 276-man Eight Banner unit under Major Fu Long, fighting to the last man at Tianzunmiao in Zhejiang Province, beat back the onslaught of British invaders five times in succession. In another battle fought in Zhenjiang City, Jiangsu Province, 1,500 Eight Bannermen yielded no ground in defiance of an enemy force ten times their strength. The Second Opium War of 1856-60 ended with Russia annexing more than a million square kilometers of northeast China. Local Manchus and people of other nationalities in this area waged tenacious resistance against the aggression and colonialist rule of Russia.” |

See China, National Humiliation and Foreigners in the article THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY: PATTERNS, IDENTITY AND FOREIGNERS factsanddetails.com

Foreigners and Trade in Ming- and Qing-Era China

As elsewhere in Asia, in China the Portuguese were the pioneers, establishing a foothold at Macao (Aomen in pinyin), from which they monopolized foreign trade at the Chinese port of Guangzhou (Canton). Soon the Spanish arrived, followed by the British and the French. Trade between China and the West was carried on in the guise of tribute: foreigners were obliged to follow the elaborate, centuries-old ritual imposed on envoys from China's tributary states. There was no conception at the imperial court that the Europeans would expect or deserve to be treated as cultural or political equals. The sole exception was Russia, the most powerful inland neighbor.

In 1636, King Charles I authorized a small fleet of four ships, under the command of Captain John Weddell, to sail to China and establish trade relations. At Canton the expedition got into a firefight with a Chinese fort. Other battles occurred after that. The British blamed the failure in part on their inability to communicate.

American ship filled with Chinese goods

In 1820, China accounted for 29 percent of the world's gross domestic product and China and India together accounted for more than half of the world’s output. Foreigners thought they could get rich in China. There is a famous story about an 18th century Englishman who thought he could make a fortune in the textile business by convincing every Chinese person to extend the length of their shirt tails by one inch. A Harvard historian told Smithsonian magazine, “People signing on to voyages to Asia weren’t just looking to make a living, They were looking to make it big.”

See Separate Article QING-ERA FOREIGN TRADE factsanddetails.com

Trade in Canton

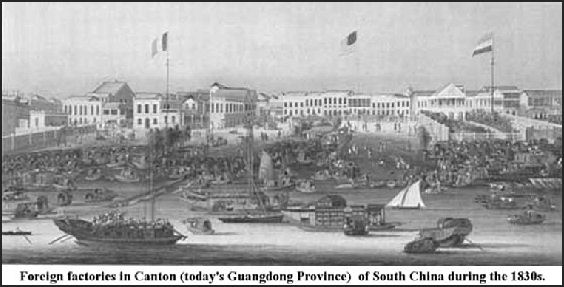

Up until the late 17th century, Western traders were allowed to conduct business only in Macau, a Portuguese enclave 75 miles south of Canton. In 1685, the powerful Qing emperor Kangxi was persuaded that he might profit from an expansion in trade and thus he permitted Western merchants to trade in Canton itself, which at that time was a bustling city along the Pearl River with about a million people.

Trade with Europe expanded in the 18th and 19th centuries. Favorable concessions were given to French and British traders, who set up shop on the East Coast of China. The reasoning was that if they were preoccupied with trade they would not cause mischief. Failure to keep pace with Western arms technology and the isolation of the Qing dynasty made it vulnerable to attacks from European weapons and exposed China to European expansion.

The lives of Western traders in Canton were greatly restricted. They could only come to Canton half of the year and then were forced to live in ghettos outside Canton's walls and were not permitted to bring their families (who were required to stay in Macau). They were also forbidden from boating on the river and trading with anyone other than authorized representatives of the Emperor, who tried to bilk the foreigners for everything he could get. The "foreign devils" worked out of offices called "factories" where the local people came by to stare at their big noses. Their vessels were required to anchor ten miles downstream on the Pearl River at Whampoa.

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “Foreigners— even on trade ships — were prohibited entry into Chinese territory. The exception to the rule was in Canton, the southeastern region centered on modern-day Guangdong Province, which adjoins Hong Kong and Macao. Foreigners were allowed to trade in the Thirteen Factories district in the city of Guangzhou, with payments made exclusively in silver. The British gave the East India Company a monopoly on trade with China, and soon ships based in colonial India were vigorously exchanging silver for tea and porcelain. But the British had a limited supply of silver. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

Merchant guilds trading with foreigners were known as "hongs," a Westernization of hang, or street. The original merchant associations had been organized by streets. The merchants of the selected hongs were also among the only Chinese merchants with enough money to buy large amounts of goods produced inland and have them ready for the foreign traders when they came once a year to make their purchases.

“The Chinese court also favored trading at one port because it could more easily collect taxes on the goods traded if all trade was carried on in one place under the supervision of an official appointed by the emperor. Such a system would make it easier to control the activities of the foreigners as well. So in the 1750s trade was restricted to Canton (Guangzhou), and foreigners coming to China in their sail-powered ships were allowed to reside only on the island of Macao as they awaited favorable winds to return home.”

Frustrations About Trade with China Before the Opium Wars

The Qing dynasty's restrictions on foreign trade increasingly frustrated Europeans, especially the British. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “For many years this system was acceptable to both the Chinese and the Europeans. As the demand for tea increased, however, and the Industrial Revolution led them to seek more markets for their manufactured goods, the British began to try to expand their trade opportunities in China and establish Western-style diplomatic relations with the Chinese.[Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultants Drs. Madeleine Zelin and Sue Gronewold, specialists in modern Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“In the later half of the eighteenth century, the British East India Company sought to expand their trade with China, but the British traders soon found that they had little to offer the Chinese other than silver — and opium. Furthermore, the Qing emperors stipulated that the British trade only with a limited number of licensed merchants, did not allow the British to communicate directly with Qing officials, and limited the trade to the adjacent ports of Macao and Guangzhou (Canton). Furthermore, the taxes and fees charged by Qing officials in the port of Guangzhou were not to the liking of the British. The British East India Company continued to come to China because the tea trade was — despite the terms of trade — quite profitable. Nonetheless, the British East India Company was not satisfied with the terms of trade.

“This brought them immediately into conflict with the Chinese government, which was willing to allow trade without diplomatic relations, but would only allow diplomatic relations within the traditional tribute system that had evolved out of centuries of Chinese cultural leadership in Asia. In exchange for trading privileges in the capital and recognition of their ruler, neighboring states would send so-called tribute missions to China. These envoys brought gifts for the emperor and performed a series of bows called the "kow-tow" (koutou).

“Aside from a handful of foreigners who lived permanently in Peking (Beijing) and served the emperor, foreigners only visited the capital on such tribute missions. Therefore, when British citizens came to Peking in the late eighteenth century, their purpose was misunderstood. When they refused to follow the centuries-old system of tribute relations and began demanding both expanded trade and the establishment of embassies in the capital, they were immediately resisted and seen as challenging the Chinese way of life.

Lord Macartney’s Mission to China

In 1792 Great Britain sent a diplomat, Lord George Macartney (1737-1806), to present its demands to the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799; r. 1736-1796). According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “One of the most famous British attempts to expand trade with China demonstrates the miscommunication between the two nations. Lord Macartney led a mission in 1793 to the court of the Qianlong emperor of China. This emperor reigned over perhaps the most luxurious court in all Chinese history. He had inherited a full treasury, and his nation seemed strong and wealthy enough to reach its greatest size ever and also to attain a splendor that outdazzled even the best Europe could then offer. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultants Drs. Madeleine Zelin and Sue Gronewold, specialists in modern Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

With the cooperation of the British Crown, Lord Macartney was sent to the court of the Qianlong emperor as representative from George III of England (1738-1820) to convince the Chinese emperor to open northern port cities to British traders and to allow British ships to be repaired on Chinese territory. Macartney was received with great ceremony by the Qing officials and by the elderly Qianlong emperor himself. Lord Macartney was able to communicate King George’s wishes directly to the Emperor. This also included the British desire for a convenient offshore island as a permanent trading post, more ports opened to trade, and diplomatic representation in Beijing.

“Macartney arrived in North China in a warship with a retinue of 95, an artillery of 50 redcoats, and 600 packages of magnificent presents that required 90 wagons, 40 barrows, 200 horses, and 3,000 porters to carry them to Peking. Yet the best gifts of the kind of England had to offer — elaborate clocks, globes, porcelain — seemed insignificant beside the splendors of the Asian court. Taken on a yacht trip around the palace, Macartney stopped to visit 50 pavilions, each "furnished in the richest manner... that our presents must shrink from the comparison and hide their diminished heads," he later wrote. Immediately the Chinese labeled his mission as "tribute," and the emperor refused to listen to British demands. He also ordered Macartney to perform the kow-tow and dashed off the following reply to the British king.”

The Qianlong emperor’s responded to the British requests with two edicts. In the fifty years after Macartney's visit, Western powers pushed their demands on China further, leading to war and the gradual shift from tribute to treaty relations.

See Two Edicts from the Qianlong Emperor, which were the Qianlong emperor's responses to the Macartney mission. afe.easia.columbia.edu

Tea, Opium and Cotton Trade Before the Opium Wars

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Two things happened in the eighteenth century that made it difficult for England to balance its trade with the East. First, the British became a nation of tea drinkers and the demand for Chinese tea rose astronomically. It is estimated that the average London worker spent five percent of his or her total household budget on tea. Second, northern Chinese merchants began to ship Chinese cotton from the interior to the south to compete with the Indian cotton that Britain had used to help pay for its tea consumption habits. To prevent a trade imbalance, the British tried to sell more of their own products to China, but there was not much demand for heavy woolen fabrics in a country accustomed to either cotton padding or silk. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University,consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Tea became a major Chinese export product to Britain. The first tea arrived in London from China in 1652. By the late 18th century and early 19th century traders from newly industrialized Britain were importing millions of pounds of tea from China. The British had hoped to trade finished goods such as textiles for tea and silk without having to go through the Emperors' greedy middlemen, but that didn't happen. Imperial China had no need for foreign products and they were importing virtually nothing from Europe. In an effort to get the Chinese Emperor to open up markets outside of Canton, British King George III, sent a regent to China that was welcomed with great ceremony but was told China has "no need of the manufactures of outside Barbarians."

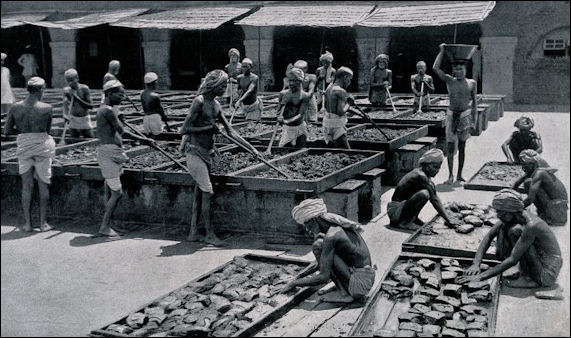

. To remedy the situation, the foreigners developed a third-party trade, exchanging their merchandise in India and Southeast Asia for raw materials and semiprocessed goods, which found a ready market in Guangzhou. By the early nineteenth century, raw cotton and opium from India had become the staple British imports into China, in spite of the fact that opium was prohibited entry by imperial decree. The opium traffic was made possible through the connivance of profit-seeking merchants and a corrupt bureaucracy. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Manufacture of opium in India

Opium as a Medium of Exchange

The British East India Company built up a huge debt for silk, tea and lacquerware.The unfavorable balance of trade between Britain and China and resentment over China's restrictive trading practices set in motion the chain of events that led to the Opium Wars When the United Kingdom could not sustain its growing deficits from the tea trade with China (partially also because the Qing imperial court refused to open the Chinese market for British goods), it smuggled opium into China.

The British had few things that the Chinese wanted so opium, grown in India, was introduced as a new medium of exchange. Opium was the perfect commodity for trading. It didn't rot or spoil, it was easy to transport and store, it created its own market and it was highly profitable. The standard measurement for opium was a 135-pound chest, which sold for as much as a thousand silver dollars. The Chinese referred to opium as "foreign mud" or "black smoke" and sometimes called it yan, which entered the English language as "yen" ("a sharp desire or craving"). [in Chinese, opium has usually been called ya-pian, a transliteration. It was also called Afurung, another, more elegant transliteration, and dayen, big smoke. Yan is the Cantonese pronunciation of Mandarin yin, which means addiction, not opium. Mandarin yen means smoke, as in dayen. Different words.]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The only solution was to increase the amount of Indian goods to pay for these Chinese luxuries, and increasingly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the item provided to China was Bengal opium. With greater opium supplies had naturally come an increase in demand and usage throughout the country, in spite of repeated prohibitions by the Chinese government and officials. The British did all they could to increase the trade: They bribed officials, helped the Chinese work out elaborate smuggling schemes to get the opium into China's interior, and distributed free samples of the drug to innocent victims. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University,consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Opium in China

Opium was well known in China before the Opium Wars although its quality was inferior to the opium brought from India by the British. In the 1600s, the habit of smoking opium became popular in Formosa (now Taiwan) after Dutch sailors introduced tobacco smoking and residents of the island mixed tobacco and opium. The Formosans introduced the custom to the mainland, where tobacco was abandoned and opium was smoked alone.

Isabel Hilton wrote in The Guardian, “Opium had been consumed in China since the eighth century and several emperors had sung its praises. It began to be smoked with the introduction of tobacco in the late 16th century, turning its consumption from a medicinal to a social habit. By the 1830s, China was producing large quantities of opium domestically, though the imported drug was judged superior. The British traders argued, disingenuously no doubt, that they were merely supplying an existing demand, delivering the opium to a network of Chinese traders who distributed it across the empire. “[Source: Isabel Hilton, The Guardian, September 11, 2011]

The British-supplied opium was very popular in China. Rich and poor Chinese alike gathered in opium dens called divans to smoke the dreamy drug, and millions of Chinese — government officials, merchants, court servants, sedan bearers — became addicted and subdued. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““The cost to China was enormous. The drug weakened a large percentage of the population (some estimate that 10 percent of the population regularly used opium by the late nineteenth century), and silver began to flow out of the country to pay for the opium. Many of the economic problems China faced later were either directly or indirectly traced to the opium trade. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University,consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

In 1830, the British dependence on opium for medicinal and recreational use reached an all time high as 22,000 pounds of opium is imported from Turkey and India.In the 50 year period between 1780 and 1830 China’s annual opium imports increased from 75 tons to 900 tons (Chinese sources say that during the early years of the reign of Chian Lung / Qianlong, no more than 200 cases of opium were imported annually. By 1830, 20,000 cases were imported annually, and by 1838, more than 40,000 cases). The opium trade significantly ate into the China's foreign trade reserves. By 1836, it transformed a huge trade surplus into a huge trade deficit.

Opium Business and China

Lin Wexu

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, opium was the world's largest traded commodity and Britain operated the world's largest drug cartel. The opium trade was dominated by the British East India Company, which oversaw the cultivation and processing of opium in India that was sold at auctions in Calcutta. About a six of India's revenues and much of the money for the Royal Navy came from the opium trade.

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: “Starting in in the mid-1700s, the British began trading opium grown in India in exchange for silver from Chinese merchants. Opium was illegal in England, but was used in Chinese traditional medicine. However, recreational use was illegal and not widespread. That changed as the British began shipping in tons of the drug using a combination of commercial loopholes and outright smuggling to get around the ban. Chinese officials taking their own cut abetted the practice. American ships carrying Turkish-grown opium joined in the narcotics bonanza in the early 1800s. Consumption of opium in China skyrocketed, as did profits. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

In spite the Emperor's objections to the business, the opium trade boomed in China. In 1773, the British unloaded 150,000 pounds of Bengal opium in Canton to pay off their foreign debt. By 1800, they were exporting 200,000 pounds of opium a year to China. The British justified their involvement in the opium trade by saying that they were only trying to meet demands for the drug in China and Chinese officials encouraged the business.

Opium was also brought to China by American ships from Turkey. Englishmen, Scotsman, Parsis in Indian and prominent families in Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore all made fortunes off the opium trade. Ancestors of presidents Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt were partners in the United States's largest opium firm; and profits from the opium trade in the United States were reinvested in railroads and factories and used to finance universities and hospitals.

Roblin wrote: "Some British had moral objections to the opium trade, but they were overruled by those who wanted to increase England's China trade and teach the arrogant Chinese a good lesson. Meanwhile, Chinese authorities had indicated they would allow trade to resume in non-opium goods. Lin Zexu even sent a letter to Queen Victoria pointing out that as England had a ban on the opium trade, they were justified in instituting one too. The letter never reached her, but it eventually appearred in the Sunday Times."

Efforts By China to Clamp Down on the Opium Trade

destroying opium in Canton

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The government debated about whether to legalize the drug through a government monopoly like that on salt, hoping to barter Chinese goods in return for opium. But since the Chinese were fully aware of the harms of addiction, in 1838 the emperor decided to send one of his most able officials, Lin Tse-hsu (Lin Zexu, 1785-1850), to Canton (Guangzhou) to do whatever necessary to end the traffic forever. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University consultant: Dr. Sue Gronewold, a specialist in Chinese history, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Lin was able to put his first two proposals into effect easily. Addicts were rounded up, forcibly treated, and taken off the habit, and domestic drug dealers were harshly punished. His third objective — to confiscate foreign stores and force foreign merchants to sign pledges of good conduct, agreeing never to trade in opium and to be punished by Chinese law if ever found in violation — eventually brought war.”

Sebastien Roblin wrote in This Week: Lin Zexu instituted arrested 1,700 dealers, and seized the crates of the drug already in Chinese harbors and even on ships at sea. He then had them all destroyed. That amounted to 2.6 million pounds of opium thrown into the ocean. Lin even wrote a poem apologizing to the sea gods for the pollution. Angry British traders got the British government to promise compensation for the lost drugs, but the treasury couldn't afford it. War would resolve the debt. [Source: Sebastien Roblin, This Week, August 6, 2016]

Image Sources: 1) Smuggling ships, Columbia University; 2) Canton factories, Columbia University; 3) Opium wars fighting, Ohio State University; 4) Attack of clipper ships, Columbia University; 5) Treaty of Nanking, Ohio State University; 6) 19th century map of China, Columbia University, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021