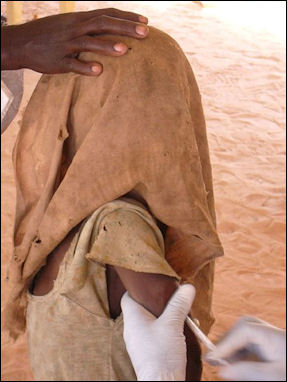

HEALTH CARE IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD (THIRD WORLD)

Child being vaccinated in Chad About 80 percent of people in developing countries rely on local health care for health care. This is often in the form of ill-equipped clinics and local healers. There are no ambulances or 911 numbers. People often have to walk, sometimes for days, to get to a decent clinic or hospital. People with medical problems often can do nothing about them because they can't afford medicine or a visit to the doctor.

Many people don’t practice rudimentary disease prevention measures such as keeping water covered, washing vegetables, brushing teeth, vaccinating children, taking the garbage away from the house and screening windows against flies and mosquitos.

Bringing good health care to poor rural areas is no easy task. One doctor who travels widely from village to village told the New York Times, "When we go out and try to inoculate babies, some peasants are very frightened and hide their kids. Or they turn their dogs on us to bite us and drive us away...We give them injections for measles, and then the kid gets a cold. So the parents come and complain. They say, 'You promised that my child wouldn't get sick!"

Some developing countries have a social security medical system that guarantees coverage for everyone, but sometimes that coverage is less than ideal. When patients go to a hospital, they have wait to get a number, then go to another window, and get another number and wait again. To get into a hospital sometimes people starting lining up at three o' clock in the morning to squeeze through the doors in a suffocating rush when hospital finally open at nine, with children and old ladies getting squashed in the process.

See Separate Articles: SERIOUS DISEASES STILL FOUND IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD factsanddetails.com; DIARRHEA AND WATER-BORNE DISEASES factsanddetails.com; TUBERCULOSIS, TB HISTORY, TREATMENTS AND DRUG-RESISTANT TB factsanddetails.com; VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES CAUSED BY MOSQUITOES, TICKS AND FLIES factsanddetails.com; MOSQUITOES factsanddetails.com YELLOW FEVER factsanddetails.com; DENGUE FEVER factsanddetails.com; MALARIA: ITS HISTORY, PARASITE AND ITS LIFE-CYCLE factsanddetails.com; COMBATING MALARIA: NETS, DIRTY SOCKS, DNA AND VACCINE EFFORTS factsanddetails.com; CHOLERA, CAUSES, SYMPTOMS, HISTORY AND FINDING ITS SOURCE factsanddetails.com; POLIO AND SMALLPOX factsanddetails.com; HOOKWORM AND WORM-RELATED DISEASES factsanddetails.com; SCHISTOSOMIASIS factsanddetails.com DISEASES IN ASIA: DRUG-RESISTANT MALARIA, RABIES AND DENGUE FEVER factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions ; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets who.int/news-room/fact-sheets ; National Institute of Health (NIH) Library Medline Plus medlineplus/healthtopics ; Merck Manuals (detailed info many diseases) merckmanuals.com/professional/index

Health Care and Money in the Developing World

Channeling heath care money into basic care is often far more cost effective than putting it into expensive treatment. "For example basic treatment for leukemia costs about $5,000 and on average adds a bit more than a month to a patient's life," The New York Times reported. "The same $5,000, used to buy vitamin A supplements for children, adds a total of 10,000 years of life expectancy."

A high medical bill can devastate a poor family. There are vaccines for measles that cost 50 cents a child, and are fairly easy to give because hardly any children wear pants. Still some children don't get them because they are too expensive.

The large Western drug companies have been criticized for their drug policies, particularly in regards to AIDS and HIV drugs, for putting profits head of saving lives.

Hospitals and Clinics in the Developing World

There are good clinics and hospitals and bad ones. Most are clean and neat, the doctors and nurses are well trained and disciplined, and good records and charts are kept on the patient, but shortages of medicines, sterilized needles and supplies are common. Many are run by church organizations.

A typical rural clinic is made of cement blocks and has unglazed windows and no screens. There is no fan, and flies are everywhere. The worst clinics have nothing and medical care is provided on a day to day basis by an 18-year villager with some knives and pliers and instructions to give out malaria pills if someone has a fever. Broken bones, in some cases, are not set, meaning that victims are disfigured for the rest of the lives, and people often die of easily treatable diseases like flu, diarrhea and measles.

Diagnosis in India Hospitals and clinics sometimes have good medicines and vaccines but lack the infrastructure — refrigerators, clean syringes and nurses — to keep them safe and adequately deliver them. Sometimes needles are reused, spreading disease and infection, and vaccines are given even though their effectiveness has been compromised by lack of refrigeration. To get around these problems, health care officials are using three cent stickers that change color when exposed to heat to indicate their contents have been spoiled, pre-filled injection devices that eliminate the need for the syringes and vaccinations that can be given orally.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to lose electricity because of power shortages, to lose radio contact with the outside world because they are unable to pay their electricity bills, and to loss their ability to provide ambulance service because there is no money for gas. The supply of basic medicines is variable. Well-stocked clinics are often that way through the work of lucky, aggressive and well-connected pharmacists.

Health Care Workers in the Developing World

Doctors do everything from set bones to perform major surgery. Nurses give treatment and medicines but generally don't care for patients (that is done by their families). Clinic workers with only a secondary education routinely pull teeth, perform appendectomies and deliver babies. Pharmacists give advise and dispense a wide variety of drugs and medicines over the counter that are only available with a prescription in the United States.

Much of the health care duties in the developing countries is taken care of by village midwives, who not only help deliver children but also perform check-ups, give health care advice, dispense birth control devices, and providing post-natal care.

Explaining why local midwives have more success than foreign doctors in improving the health of villagers, one midwife told the New York Times, "People in rural areas are very interested in being assisted by their own people. If you give people a choice, they prefer the traditional birth attendant, who knows the culture and who knows them."

An NGO program that provides reconditioned bicycle from developed countries to midwives in developing countries has been credited with saving lives by allowing the midwives to get to women who need their help much quicker.

Staff-related spending accounts for between 50 percent to 90 percent of annual budgets for health and education.

Health Care Challenges Among the Poor

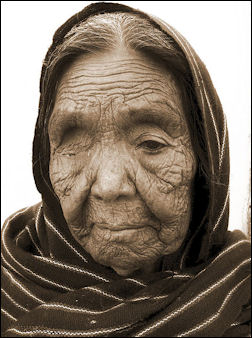

MSF health worker examines

a malnourished child Reporting from southern Ethiopia, Tina Rosenberg wrote in National Geographic, “Much of the cash they do have goes for four- to eight-dollar visits to the village health clinic to cure the boys of diarrhea caused by bacteria and parasites they regularly get from the lack of proper hygiene and sanitation and from drinking untreated river water. At the clinic, nurse Israel Estiphanos said that in normal times 70 percent of his patients suffer waterborne diseases — and now the area was in the midst of a particularly severe outbreak. Next to the clinic a white tent had arisen for these patients. By my next visit, Estiphanos was attending to his patients wearing high rubber boots. [Source: Tina Rosenberg, National Geographic, April 2010]

Sixteen miles away at the district health center in Konso's capital, almost half the 500 patients treated daily were sick with waterborne diseases. Yet the health center itself lacked clean water. On the walls of the staff rooms were posters listing the principles of infection control. But for four months a year, the water feeding their taps would run out, said Birhane Borale, the head nurse, so the government would truck in river water. "We use water then only to give to patients to drink or swallow medicine," he said. "We have HIV patients and hepatitis B patients. They are bleeding, and these diseases are easily transmittable — we need water to disinfect. But we can clean rooms only once a month."

Even medical personnel weren't in the habit of washing hands between patients, as working taps existed at only a few points in the building — most of the examining rooms had taps, but they were not connected. Tsega Hagos, a nurse, said she had gotten spattered with blood taking out a patient's IV. But even though there was water that day, she had not washed her hands afterward. "I just put on a different glove," she said. "I wash my hands when I get home after work."

Encouraging hygiene is a challenge. Wako Lemeta is one of two hygiene promoters whom WaterAid has trained in Foro. Lemeta, rather shy and poker-faced, stops by Binayo's house and asks her husband, Guyo Jalto, if he can check their jerry cans. Jalto leads him to the hut where they are stored, and Lemeta uncovers one and sniffs. He nods approvingly; the family is using WaterGuard, a capful of which purifies a jerry can of drinking water. The government began to hand out WaterGuard at the beginning of the recent outbreak of disease. Lemeta also checks if the family has a latrine and talks to villagers about the advantages of boiling drinking water, hand washing, and bathing twice a week.

Health Care Worker Absenteeism

One of the biggest problems with education and health care in the developing world, according to the World Bank, is not a lack of money but “getting teachers and doctors to report to work.” When Harvard and World Bank researchers conducted unannounced visits to clinics in rural Bangladesh they found an absentee rate of as high 80 percent in single-doctor clinics. Similar research in Indonesia found 40 percent of health workers absent from clinics. The study also covered Peru, India Ecuador and Uganda.

One solution to the this problem, the Harvard and World Bank study suggested, was experimenting with a system in which patients would be allowed to chose clinics or hospitals and public money would to go the clinics or hospitals that received the most patients. The system could both work within the public health care system and incorporate private institutions.

Health Care Programs and Waste

Studies by the University of Washington and the World Health Organization (WHO) published in Lancet in June 2009 reported that $196 billion spent on United Nations health programs had been wasted. The reports said that millions had been spent on fighting diseases such as yellow fever and malaria and providing access to HIV/AIDS drugs but beyond that it was difficult to say how all that money had been spent. The reports concluded there had been a lot of waste, with some programs even being counterproductive by undermining local services and leading some countries to slashing heath care spending.

Andy Mukherjee wrote in New York Times, “When a government with low administration capacities tries to procure medicine and doctors, one of the two — or both — is usually missing. It will be a lot better for the government to cover some of the health subsidy to families and let them buy treatment from competitive service provider.” An effort also has to be made to improve infrastructure and communications.

Hospital Customs, Shortages and Fake Medicine in the Developing World

People are afraid to go to hospitals because they believe that is where people go to die. Hospitals provide bed sheets, but the families of patients are required to bring everything else: towels, soap, dish towels, toilet paper, pajamas, cups and extra food.

Relatives are expected to feed and take care of patients while they are in the hospitals. Family members often stay in the hospital room of a sick person around the clock, and often take turns sitting by the bedsides of the sick. Out of 100 people that enter a hospital building often only about 20 percent actually have an ailment of some sort. The other 80 percent are family members who have come along to provide care and offer encouragement.

The sale of fake medicines is a problem in the developing world. In some countries as much as 25 percent of all drugs sold are counterfeit. By one estimate half of all the malaria medicine sold in Africa are fake. A World Bank study found that 30 to 70 percent of the pharmaceuticals in countries like Cameroon and Guinea are rerouted to the black market.

During the “swine” flu outbreak in 2010, poor countries didn’t have get the amount of Tamiflu and H1N1 vaccines that the developing countries had. While countries like Britain, Japan and the United States had enough Tamiflu for 25 percent of their populations, poorer nations like India, Indonesia and Guatemala only had 2 percent.

Lack of Toilets and Sanitation in the Developing World

Two out of every five people in the world have no access to safe toilets. Rather than using flush toilets they use open pits or latrines that flush waste into the streets or simply go in a nearby field. Places with sewers often have no waste-water treatment facilities and sewage is dumped directly into water supplies from which people draw their water.

According to the United Nations poor sanitation kills 1.5 million children a year. Most die of diarrhea from drinking contaminated water. Diarrhea is the world’s No.2 leading killer of children. Poor sanitation is also blamed for the spread of intestinal worms, pneumonia and cholera.

Studies have shown that providing clean water offers tremendous benefits. Health costs go down. People live longer, stay healthier and are more productive. But often there is little political will to invest in sanitation.

Jack Sim, a retired real estate entrepreneur and founder of the World Toilet Organization, has made it his goal to improve health in the developing world by introducing more toilets to villages. He said the biggest obstacle that needs to be overcome is the embarrassment factor. He told Time, “It’s a question of marketing toilets as a status symbol. I want people to aspire to owning a toilet.” As a starting point he has been promoting ecologically-sound latrines, which can cost as little as $10 a piece. Sim is also working with fertilizer businesses and engineers on effective ways to collect waste and use it to grow crops and generate biogas for cooking stoves.

Peace Corps volunteers have taught people how to build latrines with 112 mud bricks, at least 50 feet downhill from their homes.

Recycled Pacemakers

Amy Norton of Reuters wrote: “, Recycled pacemakers donated from US funeral homes could offer a safe way to get the heart devices to people in the developing world who otherwise might not be able to afford them, a US study said. An estimated 1 million to 2 million people around the world die each year because they have no access to a pacemaker, an implanted device that uses electrical pulses to the heart to maintain a normal heartbeat. [Source:Amy Norton, Reuters, October 29, 2011]

One potential, largely untapped source of pacemakers for the world’s poor could be the significant number of people in the United States who die with a still-functioning device — some 19 percent of the deceased, according to one survey of morticians in the states of Michigan and Illinois. The large majority of those are buried with the body or, if removed, thrown away as medical waste. But a small percentage are donated to developing nations through charities.

“Implantation of donated permanent pacemakers can not only save lives but also improve quality of life of needy poor patients,” wrote study leader Bharat Kantharia, of the University of Texas Health Science Center, in the American Journal of Cardiology. Kantharia and his team collected 122 pacemakers, half of which had enough battery life left — more than three years — to be used again. They were partially sterilized, then sent to a hospital in Mumbai, India, where they were sterilized again and implanted in 53 heart patients.

New pacemakers in India cost $2,200 to $6,600, not including doctor and hospital fees or the cost of the wires connected to the pacemaker.All of the patients survived the surgery and fared well immediately afterwards, with no cases of infection or pacemaker malfunctions over an average follow-up of nearly two years.While a quarter of the patients lived in areas so remote they could not be followed up after the surgery, the rest did well, Kantharia said.All but two of the 40 patients reported a marked improvement in their symptoms and quality of life. Four died, but their deaths were not linked to the pacemakers.

“All we are saying is, there are people who need a pacemaker and would not otherwise get one,” Kantharia said. “Maybe this will help them live a normal life.” A number of significant hurdles remain. One of the biggest is simply getting pacemakers from the United States to impoverished patients who need them. Another is the need for further safety studies. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only approves pacemakers for one-time use in the United States, but researchers are trying to get FDA approval to study the effectiveness of the recycled pacemakers overseas. “This study is suggestive that it’s safe,” said Thomas Crawford, an assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who is working on getting pacemakers to the developing world on a wider scale.

Eye Glasses in the Developing World

In the developing world only about 5 percent of people wear corrective glasses, compared to 60 to 70 percent in the developed world. This means that there are over a billion people — including children who can’t see blackboards or read books and drivers that can’t see road signs — that need glasses but don’t have them. The problem is especially acute in rural areas where there is little or no access to eye-care specialists. In some places there is one optician for every 1 million people . Even if the could see a doctor few can afford glasses.

Joshua Silver, an atomic physicist at Oxford , has invented self-adjusting lenses, which can theocratically be put on by anyone who needs glasses, allowing them to see normally. The glasses are comprised of soft plastic lenses that expand when silicon gel is inserted into them. The more liquid that is squirted in the stronger the correction is. Admittedly quite ugly and weird looking, the glasses have plastic syringes and small pumps that can add or subtract gel to get the correction right.

The self-adjusting lenses cost about $20. Mass production can reduce the price to a few dollars a pair. Silver, who taught optics at Oxford, has received funding from the World Bank and the British government . Among those who have bought the glasses are the American military which has given versions with small American flags and “from the American People” to poor people in Africa and Eastern Europe.

Silver has received generous offers to commercialize his invention but turned them down. Instead he founded the Centre for Vision in the Developed World. The first person who tried his glasses was a tailor in Ghana who was unable to thread a needle because of his poor eyesight. The tailor put on the glasses, squirted fluid in the lens and, with a smile on his face, quickly threaded the needle and started sewing. “I will not forget that moment,” Silver told National Geographic, “until I entirely lose my memory. “

Traditional Healers

Villages healers are often the main source of medical care. They sell herbs, act as doctors and pharmacists. and provide treatment in places where there aren't enough Western-style doctors. Many villagers have more faith their in local healers and folk medicine than they do modern medicine, and only visit a real doctor as last resort.

Healers use divining stones to diagnose patients ailments, then treat them with massages, chants, exorcism rituals and prayers and prescribe powders, herbal remedies, animal parts, teas and poultices that purportedly cure everything from gout to baldness.

Faith healing is also very common among the poor. "When you are middle class and you get sick, you first think of a doctor," one Baptist minister told Newsweek. "When you are a poor person, the first thing you think of is a miracle."

See Shaman and Animism Under Religion

Folk Medicine

People collect local plants and herbs for medicinal purposes. Many local remedies have been figured out by trial and error over generations. In some cases, villages healers often just go outside the house and wander around for a few minutes to gather the plants they need.

Some traditional herbal remedies are now being studied by botanical organizations and cancer research institutes to see if they contain promising cures. Some substances derived from healing herbs are already being marketed in other countries, but are prohibited by the FDA in United States.

Researchers often have difficulty duplicating the successes of local remedies because sometimes the plants have to picked at certain times of the year or even certain times of the day when the active ingredients are present. Or they active ingredients are only a certain part of the plant.

Artemisinin is a powerful anti-malaria drug made from Artemisia annua, a plant also known as qinghao, qing hao or sweet wormwood that is native to southern China. Developed by Chinese scientists, it is the most effective new malaria treatment, curing 90 percent patients in three days with no significant side effects.

Artemisinin a comes from Artemisia annua, a six-foot-tall plant with fernlike leaves that grows in China and Vietnam and originated from the Luofushan area of Guangdong Province in southern China. If it wasn’t for its fresh, sharp scent it would be easy to mistake Artemisia annua for any other shrub.

No one knows how Artemisia annua it was first discovered. It was prescribed as hemorrhoid treatment in the 2nd century B.C. medical treatise “Fifty-Two Remedies” and described by Ge Heng (283-363), a Taoist priest preoccupied with the search for elixirs of immortality. In his Book of “Emergency Medicine” Ge wrote that patients suffering from high fever are advised to “take a handful of sweet wormwood, soak it in a sheng [about 1 liter] of water, squeeze the juice and drink it all.” See Malaria Treatment. See Disease. See India.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets; National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various websites books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012