DENGUE FEVER

aegypti mosquito Dengue fever is a nasty, viral disease transmitted by the “Aedes” mosquito, usually the “ Aedes aegypti” , the same mosquito species responsible for transmitting human viruses such as Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. Dengue causes flu-like symptoms and rashes. It usually is not fatal, but can be especially severe for younger victims.

Dengue is the most prevalent viral infection transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, which also transmits yellow fever. More than 3.9 billion people in over 129 countries are at risk of contracting dengue. The diseases sickens up to 100 million people every year (there are also asymptomatic cases) and causes an estimated 40,000 deaths every year. There are several strains of dengue fever (the four main one are immunologically related). [Source: World Health Organization (WHO), March 2, 2020]

Research in 2013 suggests some 390 million people are infected with the virus each year, most of them in Asia. That's about one in every 18 people on Earth, and more than three times higher than the World Health Organization's previous estimates. According to Associated Press: “Known as "breakbone fever" because of the excruciating joint pain and hammer-pounding headaches it causes, the disease has no vaccine, cure or specific treatment. Most patients must simply suffer through days of raging fever, sweats and a bubbling rash. For those who develop a more serious form of illness, known as dengue hemorrhagic fever, internal bleeding, shock, organ failure and death can occur. And it's all caused by one bite from a female mosquito that's transmitting the virus from another infected person. [Source: Associated Press, November 15, 2013]

“Dengue typically comes in cycles, hitting some areas harder in different years. People remain susceptible to the other strains after being infected with one, and it is largely an urban disease with mosquitoes breeding in stagnant water. Several countries in Southeast Asia, including Laos, Thailand, Vietnam and Singapore have experienced their severe outbreaks in recent decades. Cases have also been reported in recent years outside tropical regions, including in the U.S., Japan and Europe.

See Separate Articles:VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES CAUSED BY MOSQUITOES, TICKS AND FLIES factsanddetails.com; MOSQUITOES factsanddetails.com YELLOW FEVER factsanddetails.com; MALARIA: ITS HISTORY, PARASITE AND ITS LIFE-CYCLE factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions ; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets who.int/news-room/fact-sheets ; National Institute of Health (NIH) Library Medline Plus medlineplus/healthtopics ; Merck Manuals (detailed info many diseases) merckmanuals.com/professional/index

Dengue Fever Symptoms

Dengue fever is characterized by sudden onset of fever; intense pounding, frontal headaches; aching bones and joints; pain behind the eyes; a rash similar to measles; nausea and vomiting; and a feeling of being too sick to eat anything. Other symptoms include severe sweats, chills, and excruciating chest pains. Severe cases can cause internal bleeding, liver enlargement, circulatory shutdown and death.

Dengue fever lasts for seven days. Symptoms generally show up between four and seven days after infection. Extreme cases occur mostly in older children and adults with weakened immune systems. Nine out of 10 people who get dengue fever don’t even feel it or get a mild case in which they feel something akin to a slight flu. People who get full-blown dengue fever are sick for a week or more. Many patients have a rash, which appears 3 to 5 days after the onset of the disease, and experience severe emotional and mental depression during the recovery period. Most cases of the disease are benign and self-limiting although convalescence may take a long time. Tests for dengue rely on the presence of antibodies, which can take up to a week to develop.

A few people with dengue fever suffer gastrointestinal bleeding. Fewer still suffer brain hemorrhages. In about 1 percent of cases dengue fever can cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic disease called dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) that occurs when capillaries leak. It usually occurs during a second infection with another of the four types of dengue virus. DHF damages the lymph and blood vessels and may cause the circulatory system to collapse. Symptoms include uncontrollable bleeding from the eyes and nose and even through the skin and the enlargement of the liver — and it can result in death. Those that die of dengue fever often get DHF hemorrhaging in the final stage of the sickness. Failing to realize they are infected, they go don’t get treatment soon enough and lose blood plasma and go into shock after the initial fever passes. Some victims die within 10 hours of developing serious symptoms if they don’t get appropriate treatment.

Those who get the disease develop an immunity to the strain they were infected by but are more likely to get DHF and get seriously sick if they get infected with a second, different strain. Scientists are not sure why this happens but think it may be because the immune system reacts the second time as if the invader were the first strain, wasting precious energy and leaving the body vulnerable to an attack by the second strain. Many doctors believe that since so few people show symptoms the when get dengue those that do display symptoms probably have gotten the disease a second time from a second strain. Getting the disease twice for two different strains seems to provide immunity for life from all strains of dengue fever.

History of Dengue Fever

Where dengue fever is found in Africa, Asia and Oceania Dengue fever and yellow fever are so closely related they are regarded as sister diseases. Dengue was first identified about 300 years ago but remained an isolated problems until it was spread around Asia and Pacific by troops during World War II. Both dengue and yellow fever were thought to have been close to eradication in the 1940s but have since made comebacks. The disease took off in crowded conditions in Asia. By 1975 it was a leading cause of hospitalization and death among children in the region.

From Southeast Asia dengue fever made its way to India, Africa, the eastern Mediterranean and finally to the Americas where it emerged as a threat in the 1970s just as campaigns to stamp out yellow fever in Latin America were declared a success.

Several new strains of the dengue virus have emerged in Asia and Latin America since the mid-1970s. The disease was a problem in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1980s and 90s. It first took hold in Central and South America and progressed into Caribbean and the southern United States. There were 116,000 infections in Latin America alone in 1990. Cases have been reported in Florida and Hawaii.

In recent years there have been severe outbreaks of nasty forms of dengue fever and of DHF in Southeast Asia.

A dengue fever pandemic swept across the Western Pacific in 1991 and 2004, peaking with 350,000 cases in 1998, according to the WHO. In the early 2000s, tens of thousands of people were infected with dengue fever in Thailand. More than a hundred people died in 2001. Particularly hard hit were Bangkok and the central provinces of Chonburi and Nakhon Sawan. In some places outbreaks occur every two or three years as immunity after not getting the disease only lasts a year. The disease has also made its presence known in Southeast Asia in the late 2000s and early 2010s. In 2007, the number of cases of dengue fever in Thailand rose 36 percent . As of mid-2007 the disease had killed 17 people and affected more than 21,000 people. The increases was blamed on the early arrival of the rainy season. See Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore and Southeast Asian countries.

One Person’s Experience with Dengue Fever

Dengue fever often begins with a headache and an achy feeling. The headaches seems to migrate towards the eyes behind the sockets as fever takes hold rises. If full-blown symptoms take hold the pain spreads throughout the entire body.

One suffer who was struck by dengue fever in Singapore wrote in the New York Times, “Not for nothing is dengue also known as breakbone fever...I, for one, felt as though someone had tied a Brink’s truck to my lower back. My skin was flushed, I could not eat, and I slept 12 to 14 hours at stretch. When I went to my doctor two days later, I could hardly open my blood-stained eyes...The doctor had little choice but to send me home with the painkiller Panadal and some muscle relaxants.”

“A week after my first feverish night, a doctor looked at the tiny pinpricks of blood under the skin on my shoulders, and sent me for a blood test, which confirmed that I had dengue...My first blood tests also revealed that my platelets — the cells that allow blood to clot and prevent hemorrhaging — had dropped to almost half of what doctors consider normal. They weren’t low enough for me to be hospitalized for transfusions, fortunately, but they were low enough to earn me daily blood tests to make sure.”

“The virus had inflamed my liver, as well, sending liver enzymes into my bloodstream, another mysterious symptom. For weeks after my fever subsided and my platelets returned to normal, I was still laid out, lethargic and giddy. My appetite returned slightly, but food and even water tasted strangely unpleasant...A month of afternoon naps later I was completely recovered.”

Dengue Fever Mosquitos

spread in Western Hemisphere Dengue fever is transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitos. "Aedes" means “unpleasant.” The mosquito is also the principal vector for yellow fever and Zika. Aedes aegypti is a small, dark mosquito with white markings and banded legs. It originated in Africa and made its way around the globe centuries ago when it hitchhiked on transoceanic voyages.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is common in Asia and Latin America. It prefers to feed on humans during the daytime and are most frequently found in or near human habitations. They are most likely to bite during a period of several hours in the late afternoon before dark and for several hours after day break.

In 2007, scientists published the genome — a map of all the DNA — of the Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that carries yellow fever and dengue fever. It turns out the genetic make up of this mosquito is more complex than the one that carries malaria. Both Aedes aegypti and the mosquito that carries malaria have about 16,000 genes but the genome for Aedes aegypti is about five times larger.

Dengue Fever Treatment and Testing

Dengue fever has no vaccine and no cure. Most victims that show symptoms recover on their own with rest and hospital care. Severe cases are treated through rehydration or by blood transfusions. The juice of the papaya leaf stops the destruction of platelets which have been the cause of many dengue fever deaths. Ayurveda researchers have found that enzymes in the papaya leaf can fight a host of viral infections, not just dengue, and can help regenerate platelets and white blood cells. [Source: Wikipedia]

In Singapore, hospital treatment lasts about 10 days. When outbreaks occur many hospitals in Singapore experience a shortage of hospitals beds. To cope with the strain, as has been the case with Covid-19 in many places, hospitals postponed non-emergency operations to accommodate the dengue patients. During dengue fever outbreaks in Singapore general practitioners and polyclinics are alerted to look for cases of dengue and are ordering more patients to have their blood tested for suspected dengue. The test, which takes fifteen minutes, is based on platelet count. Dengue sufferers have 100,000 or lower platelet count as compared to 140,000 to 400,000 of a healthy person. If a suspected dengue is diagnosed, the patient is referred to a hospital for more accurate testing.

In July 2005, Veredus Laboratories, a Singapore life science start-up company, launched a DNA- and RNA-based diagnostic kits for dengue, avian influenza and malaria. The kit is based on technologies licensed from A*STAR and the National University of Singapore. Another Singapore company, Attogenix Biosystems, also developed a biochip called AttoChip which has successfully undergone an independent clinical trial conducted by Tan Tock Seng Hospital and is 98 percent accurate. The AttoChip identifies genes, viruses and bacteria-causing diseases from a blood sample. It can detect the presence of the dengue virus within two to three days of the onset of the virus.

Dengue Fever Prevention

Dengue fever can be avoided by staying out of endemic areas (the Center of Disease Control can tell you where they are) and protecting oneself against mosquitos. Dengue outbreaks often have followed unusually hot, rainy and humid conditions. The danger of dengue fever rises when there is a lot of stagnant water for mosquitos to breed in. In some places where it rains a lot people get infected every two or three years as their immunity from the previous illness lasts only a year and they get infected again. Turning old tires and water containers upside down are other effective measures to combat dengue fever. Health officials have also taken steps to clear thick bushes around residential areas.”

According to the World Health Organization (WHO): "in order to achieve sustainability of a successful DF/DHF vector control programme, it is essential to focus on larval source reduction and to have complete cooperation with non-health sectors, such as non-governmental organizations, civic organizations and community groups, to ensure community understanding and involvement in implementation. There is therefore a need to adopt an integrated approach to mosquito control by including all appropriate methods (environmental, biological and chemical) that are safe, cost-effective and environmentally acceptable. A successful, sustainable Aegypti control programme must involve a partnership between government control agencies and the community."

There are concerns dengue fever could spread northwards, even becoming common place in the United States, as result of global warming. Already species capable of carrying the disease have been found in 28 states in the U.S. and as far north as the Netherlands in Europe. Cases of dengue fever have been reported in all 50 U.S. states but people who had it contacted the disease abroad and brought it home.

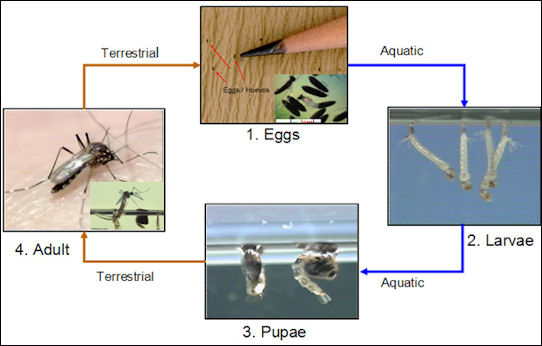

mosquito stages of development

Singapore is a leader in taking preventive measures to reduce dengue fever, During an outbreak of the disease in 2005, the Singaporean government launched a number of measures to contain the dengue outbreak, including public awareness campaigns and regular fogging with insecticides. 4,200 volunteers, 970 environmental control officers hired by construction sites, 350 so-called "mozzie busters" made up of girl guides and scouts, have participated in the preventive efforts. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Ministry of Health stepped up its monitoring of common mosquito breeding sites and launched an online map listing "hotspots" for the insects. Residents who allow mosquitoes to breed in their homes could be fined between S$100 to S$200, and heavier penalties could be issued for construction sites found with standing water. The number of officers conducting such checks have tripled. The National Environment Agency has allocated an additional S$7.5 million on top of its existing S$2.5 million budget to clear drains of stagnant water where mosquitoes breed. Singapore Land Authority has also stepped up its checks on vacant state properties. +

The National Environment Agency collected blood samples from residents of Sims Avenue, a dengue hotspot, to help track the infection. The residents were asked to provide voluntarily 5 millilitres of blood sample and a swab of saliva for the study. The samples were to be analysed for antibodies against dengue infection in the last 2 months. The National Parks Board (NParks) considered removing broad-leafed plants which may breed mosquitoes. These plants like palm trees or any plants with axils capable of trapping water, are potential breeding sites. Holes in tree trunks were also a concern. NParks workers filled these holes with sand. NParks engaged 16 pest companies to stop mosquito breeding in the parks it manages. Due to the dengue threat, some schools cancelled excursions to the parks.

Health Minister Khaw Boon Wan urged the public to help in the fight against the disease. As households are common breeding grounds for mosquitos and are less accessible for fogging, residents were told to check for stagnant water in their households and neighbourhoods and ensure there as no blockage of drains. Due to the short life cycle of Aedes aegypti mosquitos (7 to 10 days), frequent checks were necessary to eradicate dengue. These checks only took several minutes. Singapore residents also armed themselves with anti-mosquito products including insecticides, repellents and electronic mosquito traps. For repellents, experts recommend those with DEET which provides more effective and lasting protection. Some residents bought a potted plant called Citronella. The perennial grass plant, imported from Cameron Highlands, gives off a strong lemon-like fragrance which repels mosquitoes. To prevent the spread of the virus, those who were already infected with dengue were encouraged to use mosquito repellents, wear long-sleeved clothing and sleep under mosquito nets to prevent mosquitoes from biting them again and spreading the virus to others.

Combating Dengue Fever

Associated Press reported in 2013: There have been several promising new attempts to control dengue. A vaccine trial in Thailand didn't work as well as hoped, proving only 30 percent effective overall, but it provided higher coverage for three of the four virus strains. More vaccines are in the pipeline. Other science involves releasing genetically modified "sterile" male mosquitoes that produce no offspring, or young that die before reaching maturity, to decrease populations. “"I've been working with this disease now for 40-something years, and we have failed miserably," says Duane Gubler, a dengue expert at the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore. “"We are now coming into a very exciting period where I think we'll be able to control the disease. I really do." [Source: Associated Press, November 15, 2013]

Among the novel mosquito-control methods under study to tackling dengue fever are: 1) zapping male mosquitoes with a small dose of radiation, sterilizing them before releasing them into the wild; 2) Genetically modifying mosquitoes, including a method developed by Britain’s Oxitec, which gives male mosquitoes a gene to weaken their offspring so they don’t survive to adulthood; and 3) Using Wolbachia bacteria (See Below) to eliminate mosquitoes by releasing only male Wolbachia carriers. When they mate with uninfected females, the eggs don’t hatch. Each approach has pluses and minuses, but “our best hope to control the mosquitoes that make us sick is to box them in with multiple technologies,” University of Maryland biologist Brian Lovett told Associated Press . [Source: Lauran Neergaard, Associated Press, November 22, 2019]

Combating Dengue Fever with the Wolbachia Bacteria

Research employing Wolbachia, a type of bacteria that’s common in insects and harmless to people, to infect dengue mosquitoes has shown promise in blocking dengue fever and reducing the number of mosquitoes that carry the disease. Wolbachia are natural bacteria present in up to 60 percent of insect species, including some mosquitoes. However,Wolbachia is not usually found in the Aedes aegypti mosquito , the primary species responsible for transmitting human viruses such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever.

Scientists do not know exactly why Wolbachia stops Aedes aegypti from transmitting dengue, but it does. Some researchers have hypothesized that it primes the insect’s immune system to fight off other invaders.“These bacteria may persist in insects to protect against viruses,” says evolutionary biologist Ary Hoffmann, a Wolbachia expert at the University of Melbourne, told Discover magazine. Scientists believe that purposefully infecting mosquitoes will reduce their numbers and not have a negative impact on ecosystems. The method is especially promising if used with other methods such as mosquito traps and insecticide-treated materials. [Source: Linda Marsa, Discover, January-February 2012]

Scientists have been able to rapidly replace dengue mosquitoes in the wild with Wolbachia-resistant mosquitoes that don't spread the dengue virus. Australian scientists, reporting in the journal Nature in August 2011, were able to slow the spread the dengue virus by releasing Wolbachia- resistant mosquitoes into the wild. The resistant mosquitoes have an advantage in reproduction. Resistant females can mate with either resistant or ordinary mosquitoes, and all their offspring will be resistant. But when ordinary females mate with a resistant male, none of the offspring survive. [Source: Associated Press, August 24, 2011]

The Australian team uses ultrathin needles to inject embryos of the Aedes aegypti mosquito with the Wolbachia bacterium. In 2011 the researchers conducted a field trial to test their strategy. Associated Press reported: For the experiment, scientists released more than 140,000 resistant mosquitoes over 10 weeks in each of two isolated communities near Cairns in northeastern Australia, starting last January. By mid-April, monitoring found that resistant mosquitoes made up 90 percent to 100 percent of the wild population. The result is a "groundbreaking first step," Jason Rasgon of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore wrote in a commentary accompanying the paper. Rasgon, who did not participate in the study, said the next hurdle is to test the idea in areas where dengue is spread constantly, rather than sporadically as in Australia. Researchers will also have to show it works against varied strains of the dengue virus, he said.

Using the Wolbachia Bacteria to Fight Dengue Fever in Vietnam, See Separate Article DISEASES IN VIETNAM factsanddetails.com

Widespread Field Testing Wolbachia Technique

In the late 2010s, The nonprofit World Mosquito Program infected mosquitoes with Wolbachia, and released them in communities in Indonesia, Vietnam, Brazil and Australia that agreed to be test sites. Researchers say dengue cases fell dramatically, compared to nearby communities where regular mosquitoes did the biting. It was the first evidence from large-scale field trials that mosquitoes are less likely to spread dengue and similar viruses when they carry Wolbachia. “Rather than using pesticides to wipe out bugs, “this is really about transforming the mosquito,” said Cameron Simmons of the nonprofit World Mosquito Program that is conducting the research. [Source: Lauran Neergaard, Associated Press, November 22, 2019]

Lauran Neergaard of Associated Press wrote: Simmons’ team reported a 76 percent decline in dengue recorded by local authorities in an Indonesian community near the city of Yogyakarta since the 2016 release of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes. That’s compared to dengue transmission in a nearby area where regular mosquitoes do the biting. Researchers found a similar drop in a community near the southern Vietnamese city of Nha Trang. And preliminary results suggest large declines in dengue and a related virus, chikungunya, in a few neighborhoods in Brazil near Rio de Janeiro. [Source: Lauran Neergaard, Associated Press, November 22, 2019]

The approach doesn’t reduce bites. Simmons said the up-front cost is cheaper than years of spraying and medical care. The studies are continuing in those countries and others. But the findings, presented at a meeting of the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, suggest it’s possible to turn at least some mosquitoes from a public health threat into nuisance biters. “The work marks “exciting progress,” said Michigan State University professor Zhiyong Xi, who wasn’t involved with the project but has long studied how Wolbachia can turn mosquitoes against themselves. “Reducing disease “is the ultimate success of our field,” added University of Maryland biologist Brian Lovett, who also wasn’t part of the project.

“More research is needed, specialists cautioned. These studies used local health groups’ counts of dengue cases rather than blood tests, noted Penn State University professor Elizabeth McGraw. And while Wolbachia has persisted in North Queensland mosquitoes for eight years and counting, whether mosquitoes maintain dengue resistance that long in harder-hit regions remains to be seen. “The results are pretty exciting — strong levels of reductions — but there clearly are going to be things to be learned from the areas where the reductions are not as great,” McGraw said.

Malaysia Releases GM Mosquitoes to Combat Dengue Fever

Scientists released genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes in 2010 at sites in Malaysia and the Cayman Islands as part of an effort to fight dengue by limiting mosquito populations. In January 2011, AFP reported: “Malaysia has released 6,000 genetically modified mosquitoes designed to combat dengue fever, in a landmark trial slammed by environmentalists who say the experiment is unsafe. In the first experiment of its kind in Asia, about 6,000 male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were released at an uninhabited site in the central state of Pahang, the government-run Institute of Medical Research (IMR) said. [Source: AFP, January 26, 2011]

The IMR, which was tasked with carrying out the trial, said the experiment was conducted on December 21 to "study the dispersal and longevity of these mosquitoes in the field". "The experiment was successfully concluded on January 5, 2011," the institute said in a statement dated Tuesday, adding that no further releases are planned until the trial results are analysed. The insects in the experiment have been engineered so that their offspring quickly die, curbing the growth of the population in a technique researchers hope could eventually eradicate the dengue mosquito altogether.

Females of the Aedes species are responsible for spreading dengue, a deadly disease which killed at least 134 people last year in Malaysia alone. The trial has sparked widespread concern among environmental groups and non-government organisations (NGOs), and had been postponed due to their protests as well as unfavourable weather conditions. "I am surprised that they did this without prior announcement given the high level of concerns raised not just from the NGOs but also scientists and the local residents," said researcher Lim Li Ching from Third World Network.

The network is part of 29 public health and environmental groups which have repeatedly demanded the government cancel the trial, saying it was risky and could lead to unintended consequences. "We don't agree with this trial that has been conducted in such an untransparent way. There are many questions and not enough research has been done on the full consequences of this experiment," she told AFP.

Critics have also said that too little is known about the Aedes mosquito, and how the genetically modified insects would interact with their cousins in the wild. Authorities have dismissed the fears and said the trial would be harmless as the GM mosquitoes can live for only a few days. Environmentalists are concerned that the GM mosquito could fail to prevent dengue and could also have unintended consequences. Critics have said the larvae will only die if their environment is free of tetracycline, an antibiotic commonly used for medical and veterinary purposes.

Fighting Dengue Fever with Mosquito Fish and Tiny, One-eyed Crustaceans

In Savannakhet Department of Laos, local people have been encouraged to raise “mosquito fish” that eat the larvae of dengue-carrying mosquitos. One official told the Vientiane Times, “Breeding mosquito has proven one of the most effective methods in the fight against dengue fever. Since 2002, Cambodia, Russia and Malaysia have been successful using it.” The mosquito fish, or Gambusia affinis, is native to the southern and eastern United States. They have been very effective controlling mosquitos in California since they were introduced there in 1922. According to the Vientiane Times, “The fish are released into empty jars or jars that are used to collect rainwater, which are common breeding grounds for mosquitos, where they eat up any developing larvae.

Scientist were able to wipe out mosquitos that carry dengue fever in a village in northern Vietnam by using a one-eyed crustaceans that lives in ponds where mosquitos breed and has a large appetite for the larvae mosquitos that carry Dengue fever. In an experiment was pioneered by Australian and Vietnamese scientists in Nam Dinh, Vietnam: "Dengue-carrying mosquitoes were wiped out in the village of Phan Boi within 18 months,'' said Ahmet Bektas, country director for the Australian Foundation for Peoples of Asia and the Pacific, which oversees the scientific project. Reuters reported: The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene recently hailed the project as the first anywhere in the world to eradicate the dengue-carrying Aedes mosquitoes. "The great fear is that it's spreading,'' Jeremy Farrar, a dengue fever expert at Britain's Oxford University, said after observing the project in Nam Dinh, south of Hanoi. But in Vietnam, which has one of the highest regional rates of dengue infection, the shrimp-like crustacean mesocyclops -- named partly after the one-eyed maneaters of Greek mythology -- is making inroads by preventing the spread of the disease. [Source: Reuters, July 30, 1999 ^^]

It has enabled scientists in Vietnam to reduce dengue-carrying mosquitoes by 96 percent across 45 villages, completely wiping them out in at least one, Phan Boi. But the tiny creature does not act alone. Villagers ensure the mesocyclops, which occurs naturally in Vietnam and other countries, are put into household water supplies where mosquitoes commonly breed. It is too early to predict the global implications of the experiment's success, but long-time project participant John Aaskov, who works with the WHO in Australia, is optimistic. "This program is going to be of benefit wherever people want to try it, certainly throughout the region,'' said Aaskov, adding it could also be used in Africa and South America. ^^

Dengue Fever Vaccines

In March 2021, Japan's Takeda Pharmaceutical Co said it had started regulatory submissions to Europe's health regulator for its dengue vaccine candidate, which is being developed for individuals aged four to 60. Reuters reported: “The drugmaker said that the European Medicines Agency would conduct an assessment of the vaccine, TAK-003, under a procedure that also allows it to assess and give opinions on medicines that are intended for use in countries outside the European Union. Takeda said it planned to submit regulatory filings in certain Latin American and Asian countries as well as in the United States in 2021. [Source: Reuters, March 26, 2021]

Data from a late-stage trial showed the vaccine succeeded overall but failed to protect against one of the four types of the virus in children and teens who had never previously been exposed to the mosquito-borne disease.” Julie Steenhuysen of Reuters wrote: “Takeda's vaccine was 80.2 percent effective at preventing dengue among children and teens in the year after they got the shot, according to results of a Phase III study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Sanofi's Dengvaxia — the world's first dengue vaccine — had demonstrated 59.2 percent overall efficacy in the first year of follow-up based on combined results from two late-stage trials. [Source: Julie Steenhuysen, Reuters , Nov 7, 2019]

“A preliminary analysis of Takeda's vaccine suggests it may offer unbalanced protection among the four types of dengue. Experts have long been concerned that a dengue vaccine that is only partially protective could increase the risk of severe disease after exposure to a second type of the virus. The results follow Sanofi's 2017 disclosure that Dengvaxia increased the risk of severe dengue in children who had no prior dengue exposure. That news triggered an investigation in the Philippines where 800,000 school-age children had already been vaccinated. Fallout from Sanofi's vaccine has raised the bar for demonstrating the safety of future dengue vaccines.

“Among roughly a quarter of study subjects with no prior dengue exposure who got Takeda's vaccine, the shot was 75 percent percent effective at preventing all four types of dengue. Much of the vaccine's overall benefit, however, appeared in people infected with dengue 2, the type of dengue that forms the basis of the vaccine known as TAK-003. It was 97.7 percent effective at preventing dengue 2, but lead researchers said the effect was "modest" against the other three types of the virus.

“There was no difference in effectiveness against dengue 2 among those with no prior exposure to dengue and those previously exposed, and a slightly lower benefit against dengue 1 for those with no prior exposure. But preliminary evidence suggests the vaccine failed to protect against dengue 3 in children and teens with no prior dengue exposure, and there was not enough evidence to make a call about its effect on dengue 4, researchers said. The results suggest "there may be an imbalance in the vaccine, particularly with dengue 3 and maybe dengue 4, but the efficacy was very good," said Dr. Anna Durbin of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who helped develop a rival dengue vaccine with the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

“Dr Stephen Thomas, a dengue expert at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University who has been a paid adviser for Takeda, Sanofi and several other drugmakers, said the results in dengue 3 "are disappointing from the perspective that the field desires a vaccine with protective efficacy." However, Thomas said there is more data coming and more follow-up underway, and said there is currently "no indication that the vaccine is doing harm" in people previously exposed to dengue or not.

Image Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions

Text Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets; National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various websites books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022