YELLOW FEVER,

aedes Yellow fever is the second most dangerous mosquito-borne disease after malaria. It is a viral infection transmitted by “Aedes aegypti” mosquitos and is endemic to zones in tropical Africa and South America. Urban yellow fever is carried the “ Aedes aegypti” mosquito. Jungle yellow fever is an enzootic disease transmitted among nonhuman primate hosts by a variety of species of mosquitos.

Yellow fever famously halted progress on the Panama Canal in the 1900s and shaped the history of Atlantic coast cities from Philadelphia to Rio de Janeiro. Although a yellow fever vaccine has been available since the 1930s, the disease continues to afflict 200,000 people a year, a third of whom die, mostly in West Africa.

Yellow fever victims often suffer from jaundice (a liver disease that yellows the skin), hence the name yellow fever. Other symptoms include headache, chills, nausea, and vomiting. Severe cases can infect the blood, liver and kidneys.

Dengue fever and yellow fever are so closely related they are regarded as sister diseases. Yellow Fever sometimes picked by mosquitos from monkeys that carry the disease with no ill effects. Tissue and blood samples are taken from hunted monkeys to find source of disease and define infected area.

Yellow fever is found primarily in the 34 countries that make up Africa's "yellow fever belt." In the 2000s, there were around 200,000 new cases of yellow fever and 20,000 to 30,000 deaths attributed to the disease each years. Despite the availability of the vaccine the number of people that become infected with the disease had been rising for the previous 20 years according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

See Separate Articles:VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES CAUSED BY MOSQUITOES, TICKS AND FLIES factsanddetails.com; MOSQUITOES factsanddetails.com MALARIA: ITS HISTORY, PARASITE AND ITS LIFE-CYCLE factsanddetails.com

Yellow Fever Mosquito

Yellow fever is transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitos. "Aedes" means “unpleasant.” The mosquito is also the principal vector for dengue fever and Zika. “Aedes aegypti” is a small, dark mosquito with white markings and banded legs. It originated in Africa and made its way around the globe centuries ago when it hitchhiked on transoceanic voyages.

“Aedes aegypti” prefers to feed on humans during the daytime and is most frequently found in or near human habitations. They most commonly bite for several hours after day break and for several hours in the late afternoon before dark.

In 2007, scientists published the genome — a map of all the DNA — of the Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that carries yellow fever and dengue fever. It turns the genetic make up of this mosquito is more complex than the one that carries malaria. Both Aedes aegypti and the mosquito that carries malaria have 16,000 genes but the genome for Aedes aegypti is about five times larger.

Strategies used to combat mosquitoes may also work on yellow-fever-carrying mosquitoes.

See Separate Article DENGUE FEVER factsanddetails.com

History of Yellow Fever

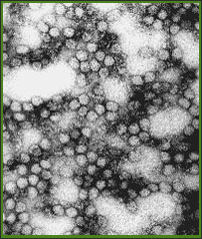

yellow fever parasite Yellow fever originated in Africa. In the 16th or 17th century, the larvae of its carrier, the “ Aedes aeyoti” mosquito was likely transported from West Africa to the New World in water casks carried aboard slave ships and found an ecological niche in its new home.

The United States suffered greatly from the disease. Philadelphia lost ten percent of its population in one outbreak in 1793, and the urban mortality rates from yellow fever reached 50 percent in some cities in the 19th century. People thought the disease was spread by the vomit or clothes of sick people. The French also suffered. In 1802, Napoleon sent 33,000 men to Haiti and the Mississippi Valley. 29,000 of them succumbed to yellow fever. He became fed with the New World. And this is one of the reasons he made the Louisiana purchase deal with the United States for such a small amount of money.

Renowned U.S. Army pathologist Walter Reed discovered the cause of yellow fever during an outbreak of the disease during the Spanish American war in Cuba. Using volunteers as guinea pigs, Reed determined that yellow fever was transmitted by the “Aedes aegypti” . Reed's work inspired a huge campaign to get rid of the disease-carrying mosquitos by killing them with fumigators and by getting rid of supplies of standing water. The number of cases of yellow fever dropped from 1,400 cases in 1900 to 37 in 1901.

The disease was controlled in Cuba and later in Panama, where the Panama canal was being built, eliminating mosquito breeding habitats (namely still water) and installing screens. After World War II, DDT was used to get rid of mosquitos around the world and yellow fever as well as malaria, dengue and other diseases were declared "under control."

In the early 1900s, John D. Rockefeller, one of the richest men in the world at that time, tried to eradicate yellow fever. He was successful wiping out in the United States but not globally.

In the 1930s, soon after the vaccine was developed, yellow fever began to disappear in Africa due to an aggressive immunization campaign. By the late 1950s it was very rare. In the 1960, the vaccinations campaign came to a halt in many African countries. By the 1980s, yellow fever was staging a comeback.

Berries from a common weed found in India shows promising fighting mosquitos that spread dengue fever and yellow fever. In the online open-access journal BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, scientists in India described how the juice and extracts from the Solanum villosum weed was particularly effective in eliminating Stegomyia aegypti larvae.

Yellow Fever Vaccination

In 1927, a Ghanian man named Asibi came down with yellow fever. Scientists isolated some yellow fever from his blood and over the years cultivated it in laboratories and fed it to mouse embryo cells and later chicken embryo cells. The virus survived this regimen but became too weak to cause the disease. A vaccine made from it, called 17D, has been given to 300 million people. Scientists are tinkering with the genetic material of 17D to come with a vaccination for dengue fever.

There is a widely available yellow fever vaccination that is given in a single dose that lasts for ten years. Many countries require travelers visiting their country to have it (some of them require evidence of the vaccination from all entering travelers, others require it from travelers coming from a country where yellow fever is found). People receiving a vaccination receive an International Certificate of vaccination completed, signed and validated with the stamp of the Yellow Fever Vaccination Center.

There is also no medical cure for yellow fever. Most victims recover on their own with rest and hospital care.

br/>

br/> Yellow Fever and Deforestation

Vittor, Maria Anice Mureb Sallum and Gabriel Zorello Laporta wrote in the The Conversation:“The virus that causes it lives in primates and is spread by mosquitoes that tend to dwell high in the canopy where these primates live. In the early 1990s, a yellow fever outbreak was reported for the first time in the Kerio Valley in Kenya, where deforestation had fragmented the forest. Between 2016 and 2018, South America saw its largest number of yellow fever cases in decades, resulting in around 2,000 cases, and hundreds of deaths. The impact was severe in the extremely vulnerable Atlantic forest of Brazil — a biodiversity hotspot that has shrunk to 7 percent of its original forest cover. [Source:Amy Y. Vittor, Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Florida, Maria Anice Mureb Sallum, Professor of Epidemiology, Universidade de São Paulo, and Gabriel Zorello Laporta, Professor of biology and infectious diseases, Faculdade de Medicina do ABCS, The Conversation, July 17, 2021]

“Shrinking habitat has been shown to concentrate howler monkeys — one of the main South American yellow fever hosts. A study on primate density in Kenya further demonstrated that forest fragmentation led a greater density of primates, which in turn led to pathogens becoming more prevalent. Deforestation resulted in patches of forest that both concentrated the primate hosts and favored the mosquitoes that could transmit the virus to humans.

Image Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cdc.gov/DiseasesConditions

Text Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; World Health Organization (WHO) fact sheets; National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various websites books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022