URAL OWLS

Ural owls (Strix uralensis) are large nocturnal owls. Both common name and scientific name of this species refer to the Ural Mountains of Russia where the type specimen was collected but otherwise they have an extremely broad distribution through much of Eurasian from much of Scandinavia in the west, through montane eastern Europe, parts of central Europe, broadly through Russia to Sakhalin Island and Japan in the east. There may be up to 15 subspecies; less if clinal variations (gradual changes in a trait or characteristic across a geographical range) are taken into consideration. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ural owls have a 1.4 meter wingspan and make their nests in cavities stumps and still-standing trees. They aggressively defend their nests. Most owls depend on camouflage and stealth to catch prey Their sharp eyes or Ural owls allow them hunt at night, Specialized feathers allow them to fly virtually silently. When prey is hiding under the snow, these owl can hunt by sound using their concave face to help channel sound to their sensitive ears. [Source: Amanda Fiegl, Sven Zacek. National Geographic, June 2012]

There are a few hundred thousand of Ural owls in Europe and millions of them in northern Asia. They mainly feed on voles and other small rodents. Pairs form in the breeding season. Males do most of the hunting during the breeding season while the female looks after the chicks. Males deliver prey to the females who break apart the flesh and feeds it to the chicks.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NORTHERN BIRDS factsanddetails.com

WHITE-TAILED EAGLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PTARMIGANS: COLOR CHANGES, DIRT AND THE SLOW MALE TRANSITION factsanddetails.com

CRANES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

CINEREOUS VULTURES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PUFFINS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Blakiston's Fish Owls

Blakiston's fish owls (Bubo blakistoni) are the world's largest owls. Found in Hokkaido, the Russian Far East (eastern Siberia), northern China, North Korea, and the Russian islands of Sakhalin, Kunashiri and Etorofu, they have a wing span of 1.8 meters (six feet) and head and body length of 70 centimeters (2.3 feet) and weighs four kilograms (8.8 pound). The Ainu people of northern Japan gave these birds many names and revered them as guardians of villages and gods that cry at night and protects the country. The Japanese have traditionally associated owls with happiness and good luck and are fond of buying owl ornaments.

Blakiston's fish owls They live in cold, temperate areas with a climate similar to those of the northern U.S., Canada and Europe. They require year-round open water to feed. They also need large trees for nesting cavities, and therefore are often found in riparian forests adjacent to rivers, welands, estuaries or the sea. The woodlands they live in tend to be forests made up of coniferous spruce and firs, or mixed deciduous trees with beech, maple, ash and elm.[Source: Erik Oien, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blakiston's fish owls are also known as Blakiston's eagle owls. They are named after Thomas Wright Blakiston, a British businessman and amateur naturalist who lived in Hokkaido in the late 1800s, and ironically has as much to do with the bird’s demise as anyone. After bringing lumber equipment half way around the world to harvest timber in eastern Siberia he was denied permission to take the trees there in 1861 and instead came to Hokkaido where he hauled away timber from the island’s rich old-growth forests.

See Separate Article: BLACKISTON’S FISH OWLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

Great Gray Owls

Great gray owls weigh around a kilogram or slightly more but are among the tallest owl, standing almost a meter in height. They have a wingspan nearly two meters across. Lynne Warren wrote in National Geographic: Great grays make their nests in broken off tree ideally in a place with good views of places with prey and where they trees are spaced apart to make flying easier.. Males hunt for animals such as chipmunks and deliver them to the female, who shreds the flesh and feeds to their owlets. Great grays are devoted parents. Canadian conservation biologist Jim Duncan told National Geographic that when prey is scarce, females starve themselves, losing nearly a third of their body weight in a single month, to maximize the amount of food given to her chicks. In the winter adults consume up to a third of their weight in rodents daily. Females in particular need to put on weight to sustain them through the competitive summer months [Source: Lynne Warren, National Geographic, February 2005]

Owlets don’t stay in the best for long. The smell of accumulated waste makes the location of the nest obvious to predators so they leave the nest even before they can fly. Most owlets when they are three or four weeks old, climb or tumble to the ground, where parents to continue to feed them through the summer. One in three Great gray chicks is killed in attacks by predators such as ravels, weasels and great horned owls or starves to death because parents can’t find enough food, Two-thirds survive until they are seven or eight weeks old, when they are able to fly. By one estimate 70 to 80 percent of great gray breeding pairs successfully fledge their young.

Owls in the lower 48 eat a variety of small rodents, including voles and gophers. Those in Alaska and Canada feed almost excessively on voles. They can hunt by sight and by sound and prefer meadows and other open spaces to hunt rather than dense forest. The owls show aggression by flaring their facial feathers, exposing the length of their beak and opening their wings. Parents will attack anything — a lynx, bear or unsuspecting hiker — that gets too close to their young. Duncan told National Geographic that being struck by such an owl was “like being wacked by a two-by-four with nails sticking out of it.”

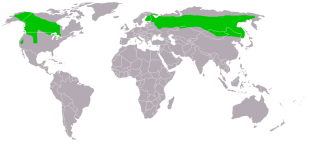

There are estimated 20,000 to 100,000 great grays in Canada and the U.S. with similar numbers in Europe and Asia. The ones in northern North America migrates extensively seeking out voles, whose populations boom and crash in different places at different times. Those living further south have a more diverse diet and tend to stay in one area, often a territory covers less eight kilometers across.

Great Gray Owls on the Hunt

Great gray owls are skilled, extrasensory hunters. Lynne Warren wrote in National Geographic: When their ears pick up the rustle of a vole or mouse beneath the snow, these owls don't just pounce, they plunge. With ice-pick talons tucked under their chins, Great Grays hurtle head-first into deep snow to snatch voles — diving with such power that they can shatter snow crust thick enough to hold a 180-pound person. They locate hidden prey with the help of large facial disks that funnel sound to their ears. When the plunge succeeds, the hunter wriggles out of the snow then carries the prey to a safe spot for consuming. This hunting technique gives great grays an advantages over other predatory birds, many of which must migrate to areas where lighter snows leave prey more accessible.” [Source: Lynne Warren, National Geographic, February 2005]

Great gray owls can find and capture voles hidden beneath almost two feet of snow, punching through hardened crusts with their legs to snag a meal. When they hunt, they tend to fly or glide toward their prey, and, once they’re in the vicinity of a vole, hover overhead for up to 10 seconds. Hermann Wagner, a retired neuroethologist who also wasn’t involved in the new work, notes that the owls’ ability to locate prey at such depths is “remarkable.”

Great gray owls seem to use quiet to their advantage. For instance, structures on the owls’ wings prevent them from making noisy flaps that would drown out the sounds of their prey, Wagner says. “What the owl does is it becomes more or less silent so that it can hear much better.”

How Great Gray Owls Pinpoint Sound to Hunt

Carolyn Wilke wrote in National Geographic: Now researchers have uncovered hints of how these birds of prey use sound to accomplish such an impressive feat. A study, published November 22, 2022 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggests the owls hover over the snow to locate muffled sounds, and that their broad faces help with this task. “Snow is really famous for absorbing sound,” says study leader Christopher Clark, an ornithologist at the University of California, Riverside, who ran a series of experiments measuring sound in Manitoba, Canada. Researchers have previously thought that the hunters zero in on rodents’ ultrasonic vibrations. But the new experiments suggest owls could also be picking up lower-pitched sounds, for instance those created by voles digging tunnels under the snow. Though people often think owls’ ears are on top of their heads, they’re actually closer to the center of their face, which is fringed by a ring of sound-reflecting feathers that funnel sounds toward their ears. [Source: Carolyn Wilke, National Geographic, November 23, 2022]

The bigger an owl’s facial disc, the lower the frequency of sound it can intercept — and the great gray owl, found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, has the biggest facial disc of any owl, Clark says. “Probably what’s going on is that the facial disc is really big to make them more sensitive to low-frequency sound.”

In February 2022, Clark and colleagues traveled to the forests of Manitoba and located seven newly made plunge holes, which are created by an owl diving into the snow after its prey. Next to each hole, they dug another, where they placed a speaker. Because of the frigid temperatures — one day was negative 30 degrees Celsius — the team had to contend with technology failing from the cold. “It was exhilarating work to do in the sense that stuff kept going wrong due to the weather,” Clark says.

Next the team used an acoustic camera, which has an array of microphones, to record the various noises in the environment. From the buried speakers, they then played white noise, a high-frequency sound, and recordings of a burrowing vole, a low-frequency sound. By removing layers of snow atop the speaker, the team recorded how the depth of snow affected sound frequencies. For instance, data from the acoustic camera revealed that while much of the white noise could escape some eight inches of snow, only the lower-frequency sounds could pass through a 20-inch-deep layer — exactly the sounds that the owls may be detecting.

The paths of sound waves from beneath the snow bend when they hit the snow’s surface. Unless an owl is directly above its prey, this bending, called refraction, causes the location where the sound seems come from to differ from its actual origin. The acoustic camera data showed that where a sound seems to come from depends on the hearer’s height above the snow, their horizontal distance to the sound, and the sound’s depth.

Snowy Owls

Snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus) are the biggest birds in the tundra and Arctic. Also known as polar owls, white owls and Arctic owls, they are strong enough to overpower a grown man. Their range is so large and inaccessible it is hard to study them. Tracking the birds revealed one flew across 1,300 kilometers of ocean in 11 days and another flew an average of 65 kilometers per days for 48 days on a 1,200-kilometer journey from Siberia to Canada. [Source: Lynne Warren, National Geographic, December 2002]

In the Harry Potter books, the Snowy Owl was Harry’s companion and courier. Lynne Warren wrote in National Geographic: “That seems perfectly fitting: swift, strong, beautiful and dauntless in caring for their young, these winged icons of the Arctic are magically fascinating — to both wizards and scientists alike...Diving out of the sky with long legs and talons outstretched, a snowy owl can drive away humans, dogs, even caribous that wander too close to its young.”

Snowy owls are currently listed as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. This means the species is considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the wild. They were listed as a species of "Least Concern". The change to "Vulnerable" reflects a significant decline in Snowy Owl populations. Because snowy owls have such a large inacessible range and they are so unpredictable, it is difficult to count them. However, available data suggests the species is declining precipitously. Whereas the global population was once estimated at over 200,000 individuals, recent data suggests that there are probably fewer than 100,000 individuals globally and that the number of successful breeding pairs is 28,000 or even considerably less. While the causes are not well understood, numerous, and complex. Some of the environmental factors are linked with climate change. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: SNOWY OWLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Eurasian Eagle Owls

Eurasian eagle-owls (Bubo bubo) are a species of eagle-owl or horned owl found in Eurasia (Europe and Asia). Also known as northern eagle owls and often just called the eagle-owl in Europe and Asia, they is one of the largest species of owl. Females can grow to a total length of 75 centimeters (30 inches) and have a wingspan of 188 centimeters (6.2 feet). Males are slightly smaller.

In addition to being one of the largest species of owl, Eurasian eagle-owls are also one of the most widely distributed, with a a total range in Europe and Asia of about 51.4 million square kilometers (19.8 million square miles) and a total population estimated to be between 100,000 and 500,000 individuals. The IUCN lists them as a species of least concern. In China their preferred habitats are mountain areas, forests, grass slopes, deserts and fields.

Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado wrote in Natural History magazine: The Eurasian eagle owl has a huge range throughout Europe and Asia, excepting only the extreme north; it occupies a wide variety of habitats, from boreal forests to Mediterranean scrubland, steppes, and deserts. With a wingspan of about six feet, it is tied for the title of world’s largest owl with its relative, the rare Blakiston’s fish owl (B. blakistoni) of Russia, China, and Japan. Although female eagle owls are slightly larger than males and their calls are distinct, the two sexes look nearly alike, with identical brown-and-white-speckled sable plumage. [Source: Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado, Natural History, November 2010]

Eurasian Eagle Owl Characteristics and Behavior

Eurasian eagle-owls weigh one to 2.2 kilograms. They have distinctive ear tufts, with upper parts that are mottled with darker blackish colouring and tawny. The wings and tail are barred. The underparts are a variably hued buff, streaked with darker coloring. The facial disc is not very defined. The orange eyes are distinctive. At least 12 subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl have been described. [Source: Wikipedia]

Eurasian eagle-owls are mostly nocturnal predators. They become active in the early evening, displaying vocally at dusk, and then moving off into the night to hunt and feed any owlets. Birds, insects, and small mammals — occasionally even foxes and other carnivores — are their prey. Most avian taxa, including owls, vocalize most at sunrise and sunset — a phenomenon known as the “dawn and dusk chorus.” Eurasian eagle owls display even after sundown and rely on sight for social communication.

Eurasian eagle-owls are non-migratory birds that tend to stay in one area. They are generally solitary except during the mating season. They have extremely good sense of hearing and visual ability during the night. They take rests in dense woods During the daytime. They vomit the hairs and animal bones that they cannot digest, and throw them in places near their nest. Eagle owls often utter sounds like "hen, hu, hen, hu" to communicate with one another. When they don't feel safe at something, they utter loud "da, da" sounds to threaten the opponents.

Eagle owls eat mice, rabbits, small birds, frogs, snakes, lizards and crabs. When hunting they quickly dive and grab their prey with their sharp claws and bill. In China their main food are mice and thus they are called "experts in catching rats".

Eurasian Eagle Owl Mating and Nesting

Eurasian eagle owls usually lay a clutch of two to four eggs, which are laid at intervals and hatch at different times. Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado wrote in Natural History magazine: Pairs usually mate monogamously for life (though they sometimes divorce or engage in bigamy), and occupy a stable territory of perhaps a square mile in area. Both sexes, but particularly males, fiercely defend their territories against interlopers — usually unmated males looking to oust the resident patriarch. Call displays are the first line of defense, and most of the time they’re sufficient. Territorial fights are rare, but they can get nasty, and often result in the death of one combatant. [Source: Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado, Natural History, November 2010]

Eagle owls prefer to nest on difficult-to-access cliffs but sometimes they nest on the ground or among low rocks. They don’t build nests, but rather lay their eggs on rocky ledges, in cave mouths, or on the ground near a rock or the base of a tree or bush. Occasionally, they take over a nest abandoned by another bird. In China they nest eggs in stone cracks and they nest 3-5 eggs each time. They hatch their eggs at the same time they nest eggs. Their young ones are quite different from adults. In seasons when they are short of food, large-sized owls swallow up small-sized owls. Such a habit seems cruel, but they ensures the survival of the strongest.

Baby Eurasian eagle owls fledge about 40 days after hatching. As they grow stronger, they venture farther and farther from the nest, even as far as nearly a mile. Yet they continue to depend upon their parents for food until they leave home for good, about 170 days after hatching. Just before owlets fledge, a strip of white feathers appears around their beaks. The white feathers become considerably less apparent once the owlets disperse. We suspected that parent eagle owls might use them to judge the relative fitness of their young.

Eurasian Eagle Owl Badges

Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado wrote in Natural History magazine: As sunset approached, the first shadows covered the cypresses and oaks that dot the landscape. On cue a male eagle owl started to call, his distinctive oohu-oohu issuing from thickets of dense brush on the cliffs. A methodical scan with binoculars failed to reveal his location, however, and with the Sun down and the light dimming rapidly, it seemed time to give up and head home. Suddenly, through the binoculars, a white flash appeared within the dark vegetation, and the male owl came into focus. Once, twice, each time he called, he inflated a white patch of feathers on his throat. [Source: Vincenzo Penteriani and Maria del Mar Delgado, Natural History, November 2010]

At night, and again at dawn before retiring to roost on a crag or in a tree for the day, Eurasian eagle owls call and inflate and deflate their throat, exposing a “badge” of feathers on their throat. The posture they assume when calling — body bowing forward, head held erect — enhances its visibility of the badge. Both males and females use such displays to announce their territorial ownership, as well as to communicate with their mates. Eagle owls’ white plumage patches and the timing of their displays may have coevolved to maximize the effectiveness of their social communication.

In daylight, animals show an extreme diversity of communication strategies, visual signaling being one of the most obvious and widely used. Variability in coloration is a particularly common signal, and bird plumage is one of the best examples. At sunset, however, colors become progressively more indistinguishable, and thus useless for signaling. Scientists have long assumed that owls and other crepuscular and nocturnal birds forgo such visual signals and rely solely on sound.

The Eurasian eagle owl, however, seemed to show otherwise. Indeed, its unpigmented throat feathers are ideal for signaling at twilight, when contrast is more important than color. Moreover, while owls have famously acute night vision, some evidence suggests that their perception of color is limited at best — so white feathers would seem a fitting way for them to communicate by night. That insight in Provence inspired our subsequent research into the eagle owl’s evening displays.

Females generally sport brighter badges than males, and both sexes’ badges were brighter in specimens collected just before the early-winter egg-laying period, when territorial and courtship displays peak, than they were in specimens collected at other times of the year. Moreover, bigger females — which may make the most reproductively fit mates — tended to have brighter badges than smaller females. Those results supported our hypothesis that eagle owls use their white badges as a visual signal, and suggested that the badges may serve as a sexual indicator of mate quality. To obtain stronger evidence, however, we needed experimental studies and direct behavioral observations.

But what does badge brightness communicate? As part of the same study, we also used data we’d collected from eight radio-tagged territorial males. We measured their breeding success over two seasons, along with the brightness of their badges. Males with brighter badges were more fecund. Taken together, the results suggest that badge brightness may represent an honest signal of male fitness and fighting ability; opponents may use it to assess their odds of winning a contest, and it may ultimately help owls avoid high-stakes, potentially fatal territorial battles.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025