PUFFINS

Puffins are a species of sea bird that generally reside in chilly waters of northern oceans. They are sometimes confused with penguins because both species have black-and-white tuxedo-like plumage and a waddling Chaplin-like walk. Puffins live in the Northern Hemisphere and can fly. Penguins live in the Southern Hemisphere and cannot fly. [Source: Kenneth Taylor, National Geographic, January 1996]

Usually when people talk about puffins there are talking about Atlantic puffins, the most colorful puffin species. These puffins have been described as cross between a toucan and a penguin. Puffins are members of the”Alcidae” family along with auks and murres. All members of this family feed on fish, are expert swimmers and divers and have thick black and white plumage. Eskimos use their feathers for clothing. Birds of this family have feet set in back of their body, giving them an awkward waddle. They perch on the flat of their foot instead of the toes as most birds. This give the appearance of looking seated when they are actually standing up.

The total breeding population probably exceeds 10 million as well several million immatures and nonbreeders. Puffins are not in danger of extinction, partly because they spend most of their time hundreds of miles away from the nearest humans, but in some areas their population have declined as a result of overfishing and hunting.

Puffin Species

There are three species of puffin. The Atlantic puffin, residing exclusively in the North Atlantic, is the species with the colorful beak, tangerine-colored feet and plumb tuxedo-like body. The other two species—the tufted puffin and horned puffin —live in the North Pacific. Rhinoceros auklets used be considered a puffin. The other 20 members of the auk family include murres, murrels, the dovekie and the razorbill.

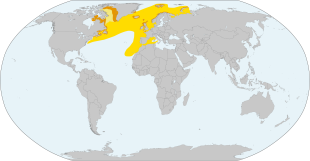

Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) live in the North Atlantic: on the coasts of northern Europe from the the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Norway in the north south to northern France and the British Isles, and in Atlantic Canada south to Maine. They winter as far south as Morocco and New York. Atlantic puffins are 32 centimeters (13 inches) long, with a 53 centimeter (21 inch) wingspan and weigh 380 grams (13 ounces). There are three subspecies: 1) F. a. arctica. 2) F. a. grabae and 3) F. a. naumanni. They are currently classified as Vulnerable on on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. [Source: Wikipedia]

Horned puffins (Fratercula corniculata) reside in the North Pacific: on coasts of the Russian Far East (eastern Siberia), Alaska and British Columbia, wintering south to California and Baja California. Horned puffins are 38 centimeters (15 inches) long, with a 58 centimeter (23 inch) wingspan, and weight 620 grams (1.37 pounds).They are classified as a species of Least Concern on IUCN Red List.

Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata) are also called crested puffins. They are found in North Pacific: near British Columbia, throughout southeastern Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and throughout the Sea of Okhotsk. They winters as far south as Honshū in Japan and California. Tufted puffins are 38 centimeters (15 inches) long, with a 63.5 centimeter (25 inch) wingspan, and weight 780 grams (1.72 pounds). They are classified as a species of Least Concern on IUCN Red List.

Puffin Characteristics and Breeding Habits

As is true with other sea birds, puffins mature late, have a low birth rate, are attentive parents and have a long life span. The average lifespan of a healthy puffin is about 15 years, long for a bird. Puffins have a special gland that allows them to drink salt water. They can dive 200 feet and hold their breath for two minutes. Puffins have back-slanting spines on the roofs of their mouths that allow them to hold many fish at one time. It is not known how puffins locate fish but they are experts at catching fish, sometimes diving as deep as 200 feet to snag a beakful. The only time that puffins carry fish is when they're feeding young. The current record for a single beakload is 62 fish.

Puffins are monogamous, usually pairing off for life at about five years of age. The pairs usually return to the same nesting site every year and if they are fortunate manage to raise one healthy chick a year. If one partner dies, the other may try to find a new mate.

The red, orange and yellow colors on beaks of the Atlantic puffin brighten and grow slightly larger in the spring and summer breeding season. David Attenborough wrote in “The Life of Birds,” "Male and female puffins develop special and identical decorations for their courtship. During the spring, they grow horny outer coverings to their beaks, handsomely striped with yellow, red and blue." When mating is over the horny covering drops off.” Both sexes possess the bright colored bill, which appear to help the birds signal one another over large distances.

Puffins lay their eggs in burrows, excavated on grassy slopes near the sea with their sharp claws and powerful beaks. Sometimes they set up nests under rocks at the foot of coastal cliffs. A single chick is raised each year. Gray and white mounds of fluffy down, new-born chicks stay in the burrows, where they are safe from gull raids. Young "pufflings' are fed by their parents, who make four or more return trips from the sea with mouthfuls of small fishes such as sand lances. Pufflings remain under their parents care until they are six month old and head out to the open sea.

Puffin Migration

Exactly where Atlantic puffins go after they breed is still somewhat of a mystery. Individuals from a given site appear to rove across the entire Atlantic. Birds banded in Iceland, for example, have been recovered in Newfoundland, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and the Azores.

About two thirds of puffins that survive their first winter at sea return to their birthplaces two or three springs later when they are ready to come ashore. The remainder settle in new colonies, possible because they found an empty piece of land ideal for a burrow.

Every August, when thousands of pufflings leave their colonies in Heimaey island in Iceland in a nighttime flight to avoid predators, many get confused by the lights and noises in the town of Vestmannaeyjar and head there instead of out to the open sea. To keep the young birds from getting injured or consumed by cats and dogs, children armed with flashlights and cardboard boxes spend hours trying to rescue the birds. Competitions are held to see who can rescue the most birds.

Scientist study puffin migration patterns and eating habits by catching bird in nets, banding them and weighing the fish dropped from their beaks. They study puffin chicks by easing fiber-optic viewing devises into their nests, coaxing them out with bamboo sticks or reaching into the burrows with one arm. Practitioners of the latter method often end up with blood-covered hands and guano-stained clothes.

Puffin Behavior and Communication

Puffins often fly above nesting areas in huge swirling masses in which birds circle in the same direction to avoid collisions, with individual birds flying in and out of the mass. Puffin expert Kenneth Taylor wrote in National Geographic that he believes that puffins do this to confuse predators such as gulls. Like school fish under attack, he says, the mass of birds make it hard for the predators to zero in on a single individual. The more puffins there are, the more likely the predator will miss its target.

Highly social birds, puffins often gather together on rocks or tussocks, to check each other out and enjoy each other's company. Immature puffins like to meet possible mates. Puffins are very curious. Instead of remaining inside there burrows where it safe, pufflings sometimes expose themselves to get a look an intruder.

Puffins have remarkable homing instincts. They are able to return to the same burrow at the same nesting sites year after year even though may have feed in the winter and fall in open seas hundreds of kilometers away. In the 1970s, dozens of puffins dead when they returned to Iceland's Heimaey island and landed on hot lava that covered their burrows.

Puffins communicate with each other by moving their eyes, heads and bodies various ways. Puffins raise their wings and head and place one foot forward when they land on a rock with other puffins. Others express their welcome by stomping their feet or scold the landing bird that he or she is "too close" with a sharp squawk. A puffin guarding it burrow or approaching its mate tucks its head against its chest and struts around with lurching, high steps.

Puffin Hunting by Humans

Inhabitants of Iceland and the Faroe Islands hunt puffins. Puffin hunters in the Wetsmann archipelago of Iceland catch the birds with a “lundaháfur”, long-handled triangular net that resembles a giant lacrosse stick. Dead puffins are used as decoys to attract more victims. Iceland's top birder, Sigurgeir Jónasson, once caught 1,204 puffins in eight hours.

Describing an Icelandic puffin hunter at work, Taylor wrote: "Puffins flying toward us are visible for only a split second as they cross the ridge, so Hallgrímur has to choose his target quickly. He swishes a long-handled net...into the path of the bird and with a deft flick makes the hit. He then quickly wrings it neck with a double twist and a pull."

Hunters pay a fee of around $100 for the privilege of hunting the birds during the July-to-mid-August puffin season. An estimated 200,000 birds are caught each year. By avoiding birds with mouthfuls of fish, they kill few breeding birds. Although the number of puffins has decreased, the puffin population is healthy and stable.

After trying some puffin in Iceland, Taylor said "the dark meat is delicious, a little like venison, with a subtle smokiness." Icelanders cook puffin in foil and say it tastes best after being hung over a sheep-dung fire. On animal right advocates that condemn puffin hunting, one puffin hunter told Taylor, they "seem to think that because puffins look so cute, we shouldn't hunt them. Yet many of those people eat chickens whose lives in captivity are much worse than the lives of our free-flying puffins. These people are not trying to understand the society here. This is a tradition.”

Places with Puffins

The Atlantic puffin only comes ashore during the spring and summer breeding season, when it can be found in nesting sites in coastal areas of eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, the Faeroe Islands and islands off of Great Britain and Ireland.

Puffins favor remote islands ravaged by cold winds with few if any human inhabitants. "Go to the edge, then to the edge of the edge, where water finally smothers land and perhaps you'll be lucky enough to see a puffin," Taylor wrote in National Geographic. Puffins like places near fishing ground on the edge of the continental shelfs, They also like gale winds because it allows them to save energy.

An estimated six million puffins nest in Iceland. The Westmann archipelago is largest puffin nesting site, with more than 4 million birds. The islands of St. Kilda—Britain's most remote archipelago— is the home of its largest puffin colony. The last residents left the island in 1930, when the Islands's only bar, the Puff Inn, was forced to close down. The Isle of May contains one of the largest puffin rookeries in eastern Britain. Daytrippers to southwest England's Lundy Island, reputedly famous for its puffins, rarely see the birds except in the form of souvenirs at local shops.

The Rost Island in the Lofoten archipelago in Arctic, Norway contains one of the largest breeding populations of puffins in the world, with over a million birds. In recent years scientists have noticed a decline in the number of puffins as well thousands of abandoned hatchlings that apparently have died because overfishing of the herring in waters around islands used by adult puffins to feed their young. After sharp declines in the number of herring, Norway began regulating their herring fisheries but the fish stocks have not fully recovered. After Norway's herring stocks plummeted in the 1960s, the number of birds at the Rost island rookery declined by more than half.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025